Significance

During repair of DNA double-strand breaks, cells must accurately anneal broken strands under temperatures that would normally promote mispairing of even small stretches of ssDNA. How single-strand annealing (SSA) proteins such as Rad52 and DdrB (DNA damage response B) overcome this thermodynamic barrier and achieve accurate strand pairing has remained unclear. Our structural studies of DdrB in complex with partially annealed DNA and supporting biochemical data reveal a mechanism for accurate annealing involving DdrB-mediated proofreading of strand complementarity. DdrB promotes high-fidelity annealing by constraining specific bases from unauthorized association and only releases annealed duplex when bound strands are fully complementary. To our knowledge, this work provides the first mechanistic understanding for accurate strand pairing during SSA-dependent DNA double-strand break repair.

Keywords: single-strand DNA annealing, DNA repair, Deinococcus radiodurans, crystal structure, DdrB

Abstract

Accurate pairing of DNA strands is essential for repair of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs). How cells achieve accurate annealing when large regions of single-strand DNA are unpaired has remained unclear despite many efforts focused on understanding proteins, which mediate this process. Here we report the crystal structure of a single-strand annealing protein [DdrB (DNA damage response B)] in complex with a partially annealed DNA intermediate to 2.2 Å. This structure and supporting biochemical data reveal a mechanism for accurate annealing involving DdrB-mediated proofreading of strand complementarity. DdrB promotes high-fidelity annealing by constraining specific bases from unauthorized association and only releases annealed duplex when bound strands are fully complementary. To our knowledge, this mechanism provides the first understanding for how cells achieve accurate, protein-assisted strand annealing under biological conditions that would otherwise favor misannealing.

How cells overcome the need to protect ssDNA from forming deleterious secondary structures and at the same time promote accurate strand annealing represents a longstanding and intriguing question in DNA repair. Single-strand DNA-binding proteins (SSBs) safeguard DNA fragments harboring single-strand regions from misannealing at biological temperatures by binding and occluding bases from potential interaction with other strands (1). Overcoming the thermodynamic barrier of accurate annealing under biological conditions requires specialized annealing proteins able to regulate access of unpaired bases from different strands. Although single-strand annealing (SSA) proteins have been identified in organisms ranging from bacteriophage to humans, how they promote faithful annealing of DNA ends containing large single-strand regions has remained unclear.

One of the best examples of single-strand annealing comes from members of the Deinococcus family of bacteria, which are renowned for their ability to withstand and accurately repair genome fragmentation, resulting in hundreds of double-strand breaks (DSBs) (2). Up to one-third of these breaks are repaired by a RecA-independent pathway that is dependent on single-strand annealing mediated by DdrB (DNA damage response B) (3–6).

DdrB was first identified from two independent analyses of the IR-induced transcriptional response of Deinococcus radiodurans (7, 8). DdrB binds ssDNA (9); however, unlike SSB, DdrB promotes accurate DNA-strand annealing (5, 10), providing evidence for a role in repair by single-strand annealing. This biological role is further supported by fluorescence microscopy data demonstrating recruitment of DdrB to the nucleoid in the early stages of repair (6) and attenuation of RecA-independent single-strand annealing repair in a ΔddrB strain (5). Although computational sequence analysis has delineated three distinct superfamilies of single-strand annealing proteins (11), similarities in function and quaternary structure suggest a shared mechanism despite divergent evolutionary origins (12–14).

Here, we report the structure of a single-strand annealing protein in complex with a partially annealed DNA intermediate to 2.2 Å. In this structure, DNA is bound to a continuous flat surface on one face of a pentameric DdrB ring assembly. Two ring structures come together in a face-to-face arrangement, sandwiching DNA strands at the interface, thereby stabilizing a partially annealed ss/dsDNA intermediate. Importantly, DdrB restricts free access of one-third of bases within the 30 base pair intermediate, thereby preventing misannealing and ensuring sufficient time to further sample full complementarity of bound strands before release of duplex DNA. This model is further validated by biochemical analysis showing that disruption of DdrB–ssDNA interactions, which restrict access of unpaired bases, significantly decreases accuracy of strand annealing. On the basis of these results we present a general mechanism for how single-strand annealing proteins ensure accurate annealing of ssDNA.

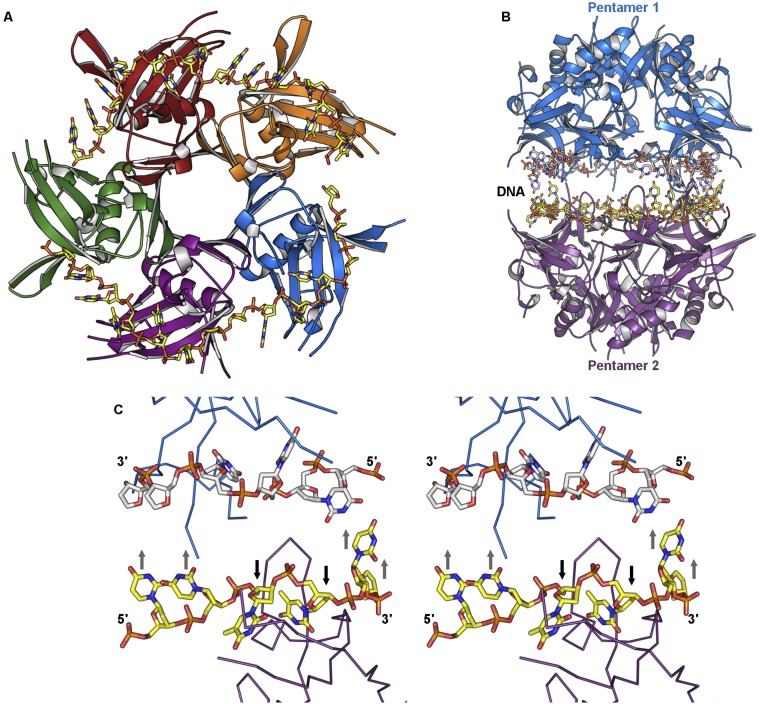

DdrB Promotes Annealing by Sandwiching DNA Strands at the Interface of Two Pentameric Rings

Prior studies of annealing proteins such as DdrB, ICP8, and Rad52 have led to a general model in which these proteins bind ssDNA along a continuous surface lining one face of their oligomeric ring structures (14–16). To further investigate this surface and its potential role in DNA annealing we determined the crystal structure of DdrB in complex with single-strand DNA. An initial structure with noncomplementary 14b ssDNA strands (Fig. S1) confirmed ssDNA binding along one extended face of a DdrB pentameric ring. Unexpectedly, two DdrB ring structures further assembled in a face-to-face complex, effectively sandwiching DNA strands at the interface. In this “encounter complex” each DdrB subunit bound six bases (30 bases per pentamer), with two bases buried and the other four exposed (Fig. S1C). Because ssDNA was not designed for self-complementarity, only partial electron density was observed for DNA at the “sandwich” interface, and most bases were not directly paired to the opposing strand (Fig. S2). Nevertheless, the structure clearly showed where DNA is bound and what an initial encounter complex looks like when noncomplementary strands are present. To further investigate how DdrB promotes accurate annealing we crystallized DdrB bound to ssDNA capable of forming a partially annealed ss/dsDNA intermediate. A substrate consisting of five tandem repeats of 5′-TTGCGC was used, which enables the GCGC motif to self-anneal, generating the potential to form a ss/dsDNA hybrid with four paired and two unpaired bases in each of the repeat sequences. The structure (Fig. 1) was solved by molecular replacement and refined at 2.20 Å to Rwork = 18.8% and Rfree = 23.3% (Table S1). All main chain residues were observed, except for a few in loop regions joining β4–β5 and β6–β7 (Fig. 2A and Fig. S3). Because of added stability available through base pairing, DNA from both strands was able to be entirely modeled. Similar to the encounter complex formed with noncomplementary ssDNA, each subunit of the pentameric ring bound six bases in a repeating pattern of two buried through protein interaction (dT1, dT2) and four exposed (dG, dC, dG, dC) (Fig. 2C and Fig. S3). dT1 is held between L87 and L97 (Fig. 3A), whereas dT2 forms a π–π interaction with the phenol group of Y125 (Fig. 3B).

Fig. S1.

Structure of DdrB in complex with noncomplementary ssDNA. (A) Top view of the asymmetric unit containing five monomers of DdrB (individually colored) and two 14-base ssDNA substrates (yellow). (B) Face-to-face assembly of DdrB pentamers with bound DNA at the interface. (C) Stereo image of bound ssDNA demonstrating the overall binding motif (two bases buried, four bases exposed).

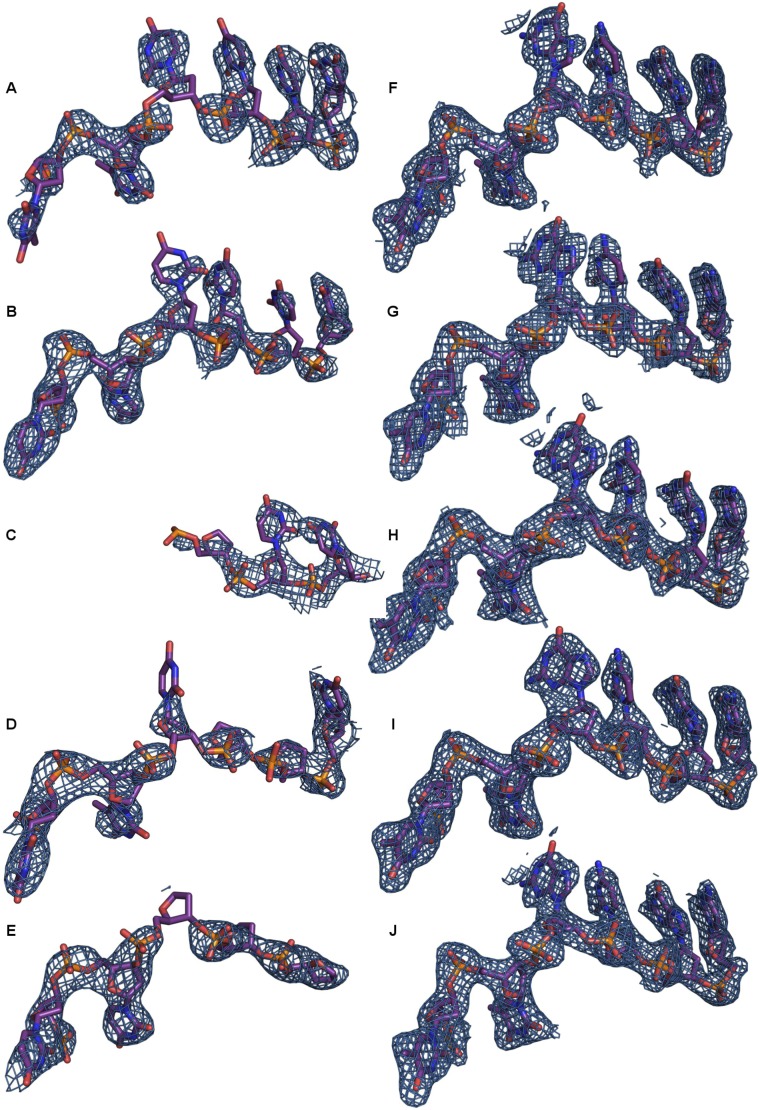

Fig. S2.

Electron density (2mFo–dFc) of bound ssDNA. (A–E) Density and model of DdrB bound to DNA substrate with limited capacity for complementarity (equimolar mixture of 5′-TTTTTTTTCGATGC and 5′-TTTTTTTTGCTACG). This structure was refined at 2.85 Å to Rwork and Rfree values of 24.8% and 28.1%, respectively (Table S1, crystal 1). Because of the low occupancy and poor quality of the map, the nature of individual nucleobases could not be determined, and so the DNA was modeled as poly dT. The overall mode of DNA binding is maintained for each subunit; however, because of limited complementarity, the exposed bases are generally disordered. (F–J) Density and model of the optimal (5′-TT GCGCTTGCGCTTGCGCTTGCGCTTGCGC) DNA substrate. Electron density maps are contoured to 1.2 σ.

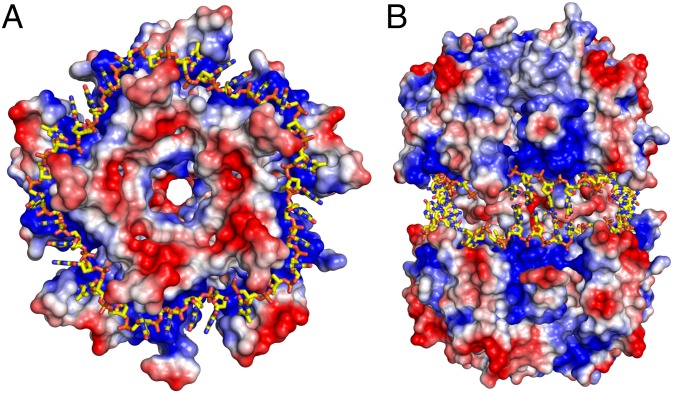

Fig. 1.

Surface electrostatic map of DdrB bound to ssDNA. (A) Top view of a 30-base ssDNA bound to the positively charged surface of a DdrB pentamer. (B) Side view of the decameric complex formed by interaction of two DdrB pentamers. ssDNA strands bound by each pentamer are partially annealed at the pentamer–pentamer interface.

Table S1.

Data collection and model refinement statistics

| Parameter | Crystal 1 | Crystal 2 |

| Data Collection | ||

| Space group | P3221 | P42212 |

| Cell Dimensions | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 76.8, 76.8, 254.8 | 131.8, 131.8, 102.3 |

| α, β, γ (o) | 90.0, 90.0, 120.0 | 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.00–2.85 (2.90–2.85) | 80.79–2.20 (2.32–2.20) |

| Rmeas | 11.8 (87.9) | 12.1 (85.7) |

| I/σ(I) | 16.5 (2.5) | 15 (2.9) |

| Completeness (%) | 100.0 (100.0) | 100.0 (99.9) |

| Redundancy | 9.3 (7.8) | 11.8 (10.1) |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 46.00–2.85 | 65.88–2.20 |

| No. reflections | 21,024 | 46,201 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 24.8/28.1 | 18.96/23.23 |

| No. atoms | ||

| Protein | 5,186 | 5,145 |

| DNA | 527 | 610 |

| Water | 58 | 546 |

| B-factors | ||

| Protein | 54.1 | 26.3 |

| DNA | 104.2 | 44.6 |

| Water | 39.2 | 35.6 |

| R.M.S deviations | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.010 | 0.011 |

| Bond angles (o) | 1.811 | 1.247 |

Crystal 1 refers to the ssDNA-bound DdrB structure with a suboptimal substrate described in Fig. S1. Crystal 2 refers to the DdrB cocrystal structure (PDB ID: 4NOE) obtained with an optimal ssDNA substrate. Statistics for the highest-resolution shell are shown in parentheses.

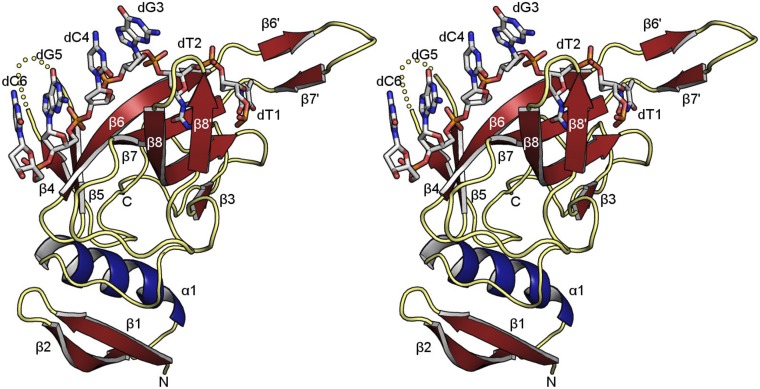

Fig. 2.

Structure of the DdrB–ss/dsDNA hybrid complex. (A) Top view of the asymmetric unit containing five monomers of DdrB (individually colored) and the 30-base ssDNA substrate (yellow). Residues in loops joining β4–β5 and β6–β7 that were not traceable are represented by dotted lines. (B) Side view of the face-to-face assembly of DdrB nucleoprotein complexes. (C) Magnified view of the base-pairing interactions taking place at the complex interface. G-C hydrogen-bonding interactions are represented by black dashes with an average donor–acceptor distance of 2.9 Å for all 60 base pairs. All structural figures were produced with PyMol (www.pymol.org).

Fig. S3.

DdrB monomer. Stereo image of a DdrB monomer (from chain A, colored in purple in Fig. 1A) bound to the 6-base 5′-TTGCGC motif. Secondary structure elements are labeled with α-helices and β-strands colored in blue and red, respectively. Missing residues in the loop regions joining β4–β5 and β6–β7 are as follows: chain A, 68–71; chain B, 67–72, 92–94; chain C, 67–72, 90–95; chain D, 67–72, 91–96; and chain E, 92–94. An additional secondary structure element, spanning residues 117–120, not observed in the two previous crystal structures of DdrB (PDBID: 4HQB, 4EXW), has been designated β8' and is annotated in the figure.

Fig. 3.

DNA-binding residues. (A–C) Magnified views of protein–DNA interactions with nucleic acids dT1, dT2, and dG3–dC6, respectively. Hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions are represented by black dashes, and π–π interactions are represented by yellow dashes. Distances are measured in angstroms.

DNA binding to one face of the pentameric ring is consistent with what has been proposed for human Rad52 on the basis of mutational studies (17). In the case of Rad52, a heptameric ring associates with a similar length of ssDNA (28 bases compared with 30 bases in DdrB) (16, 18), with each monomer interacting with four bases (19). Interestingly, Rad52 generates a repetitive pattern of hydroxyl radical protection on bound ssDNA, with three bases protected and the fourth sensitive to hydroxyl attack (19). In light of the current structures it seems likely that Rad52 also binds ssDNA in a repetitive manner.

Protein–Protein Interaction Between DdrB Rings Mediates DNA Strand Association

DdrB pentameric rings within the crystal form a face-to-face encounter complex sandwiching DNA strands at the interface (Fig. 2B). Protein–protein interactions between ring structures function to stabilize the encounter complex and also position DNA strands in the correct polarity for proper base pairing. Exposed bases (GCGC motifs) within the encounter complex are held in the correct distance and in the proper orientation to form three hydrogen bonds with each of the corresponding bases from the opposing DdrB pentamer (Fig. 2C). Encounter complex stability is therefore the net result of contributions from weak protein–protein interactions, burying a surface area of 340 Å2, and base pairing, which can account for up to an additional 1,150 Å2 of surface contact when full-strand complementarity is present. Given the large proportion of stability dependent on base pairing, the degree of strand complementarity appears to function as the main driver of complex stability and longevity. When strand complementarity is absent, an encounter complex could only exist transiently because of the limited amount of protein–protein interaction available. In addition to these contributions to encounter complex stability, DdrB also acts to inhibit nonproductive encounter complexes by limiting the total amount of binding energy available through base pairing. By restricting initial base pairing from 30 to 20 nucleotides, DdrB is able to reduce the upper limit of encounter complex stability significantly and therefore ensure that the complex will only remain intact when fully complementary strands are bound. Having more than the necessary number of bases exposed would only serve to make discriminating between full and partial complementarity more challenging. Thus, encounter complex stability mediated by protein–protein, base–base, and protein–base interaction is perfectly balanced to promote strand contact and proper orientation without trapping strands in an unproductive state when noncomplementarity is encountered.

Because ssDNA was not preannealed before crystallization, initial interaction of ssDNA with DdrB was not biased toward any particular residues being buried or exposed. Nevertheless, the crystal structure adopted the lowest possible energy state (maximum amount of annealing), implying that ssDNA is able to be repositioned along the DdrB pentamer following initial binding. It will be interesting to determine whether this involves rapid equilibrium between free and bound states and/or sliding of ssDNA strands relative to the encounter complex until optimal base pairing is achieved.

DdrB Promotes Accurate ssDNA Annealing by Restricting Access of Unpaired Bases

Partially restricting access of unpaired bases represents an elegant means of increasing annealing fidelity. If all bases were simultaneously exposed within an encounter complex one would expect there to be limited benefit to annealing accuracy over strands free of secondary structure in solution. Discrimination between accurate and inaccurate annealing would still be confounded by the small differences in binding energies between homo- and hetero-duplex products. Systematically restricting base access would overcome this difficulty by allowing annealing to occur in a controlled two-stage process involving initial sampling for general complementarity with exposed bases (step one) and a second step checking for additional complementarity between buried bases. Staged annealing would also make it possible to sample long stretches of ssDNA (30 base) for complementarity without committing to the release of partially annealed DNA until all bases (including those buried) are verified in a controlled second step.

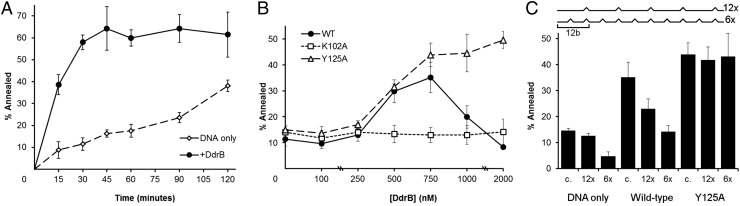

To determine if DdrB uses a two-stage annealing process that is dependent on initially restricting access to bound bases we compared annealing of DNA strands containing varying degrees of mismatches for WT and mutant DdrB. In this assay, annealing was negligible in the absence of DdrB (approximately 12% ± 3% compared with 58% ± 3% at 30 min) (Fig. 3A). As expected, DdrB significantly stimulated annealing of complementary strands (5) (Fig. 3B); however, at higher protein concentrations (>1 µM) the efficiency of annealing decreased. A second mode of ssDNA binding involving higher-order assembly of DdrB pentamers has been observed (15); however, the functional significance remains unclear. This effect is similar to what has been observed for human Rad52 (20) where reduced annealing at higher protein concentration was attributed to two opposing concentration-dependent modes of DNA binding (wrapped vs. extended) (18). Nevertheless, the fact that DdrB dramatically increases the efficiency of annealing compared with the same strands free in solution underscores the important contribution of protein-mediated interactions within Deinococcus.

Guided by the crystal structure, two mutants altering different aspects of DdrB–DNA interaction were created and tested for their effect on strand annealing. K102A, which disrupts contact with the sugar-phosphate backbone (Fig. 3) and reduces DNA-binding affinity, was included as a negative control (15). Consistent with its DNA-binding defect, K102A displayed no stimulation of DNA annealing (Fig. 4B). A second mutant, Y125A, was designed to permit unrestricted access of one of the two buried bases (dT2). Y125 accounts for most of the direct stabilizing base interaction with dT2 (Fig. 3B). When substituted to an alanine, this loss of base interaction resulted in a significant enhancement in annealing activity relative to WT protein (Fig. 4B), suggesting the release of buried bases within the encounter complex increased binding energy of the initial encounter complex. To further test effects of Y125A on annealing fidelity, two additional ssDNA oligos with decreasing complementarity were analyzed. Substrates 12x (one mismatch site every 12 bases) and 6x (one mismatch site every 6 bases) were assessed by the same annealing assay with both WT DdrB and Y125A. Although Y125A was as efficient in annealing mismatched substrates as perfectly complementary strands (Fig. 4C), WT DdrB displayed decreasing annealing efficiency with increasing numbers of mismatches and surprisingly did not significantly improve annealing fidelity relative to the unassisted control. Under more biological conditions where other factors such as SSB are present, DdrB may have increased annealing fidelity. Nevertheless, the remarkable effect of Y125A clearly demonstrates the critical importance of restricting bases at the encounter complex stage to ensure optimal protein-assisted annealing fidelity.

Fig. 4.

Single-strand annealing assay. Annealing of a 60-base 5′-6FAM labeled oligonucleotide (5 nM) to M13mp18 (1 nM) was assessed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. All reactions were performed at 32 °C, initiated by addition of the 60-base substrate, and quenched with 2.5 µM of unlabeled oligomer in 5% (wt/vol) SDS (final concentration of 250 mM and 0.5% SDS). (A) Time-course assay in the absence (◇) and presence (●) of 750 nM DdrB. (B) Concentration-dependent annealing by WT (●), K102A (□), and Y125A (△) DdrB. Reactions were quenched after 20 min. (C) Annealing with complementary (c.) and mismatched (12x and 6x) 5′-6FAM oligonucleotides in the absence and presence of 750 nM WT or mutant (Y125A) DdrB. Reactions were quenched after 20 min.

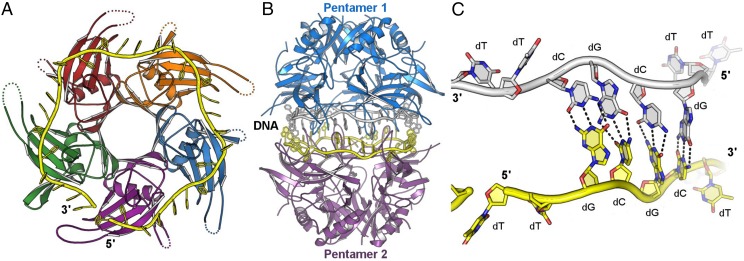

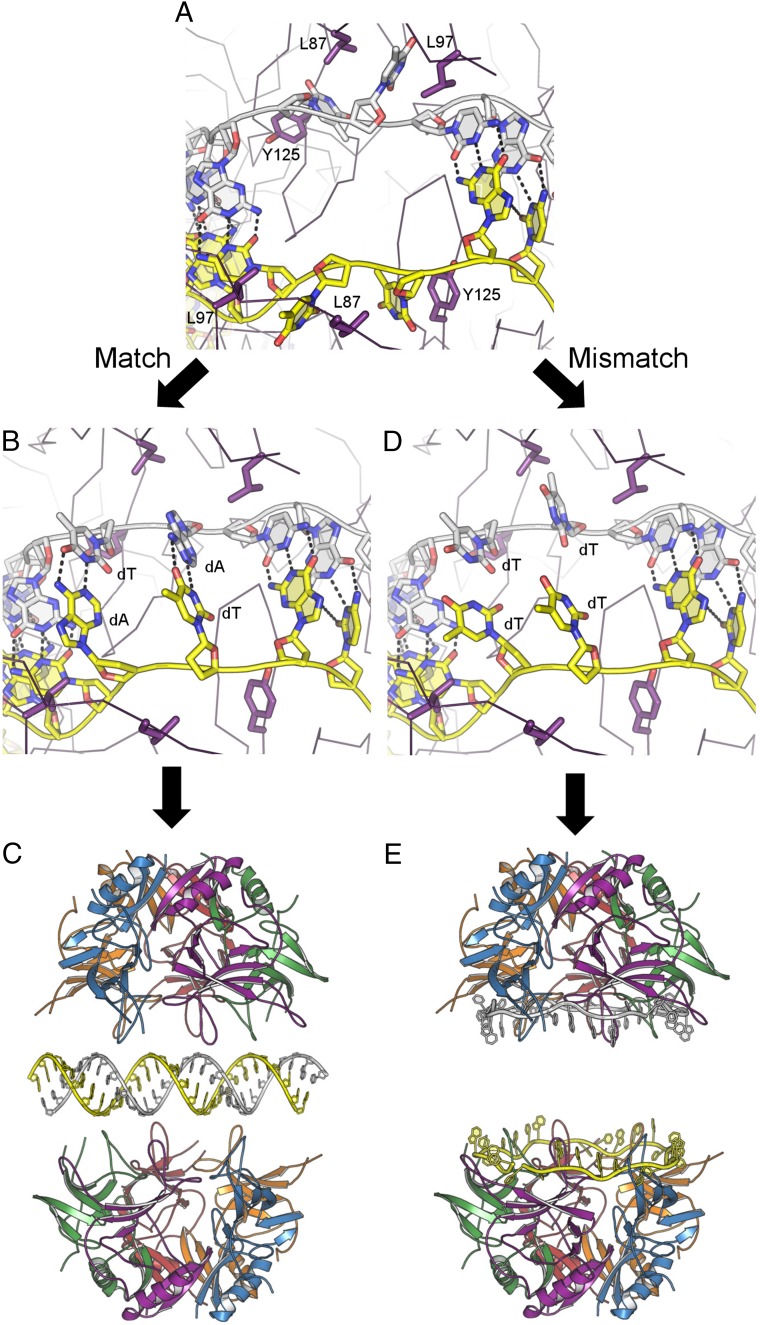

A Mechanism for DdrB-Mediated Annealing

Results presented here provide structural evidence for a mechanism of protein-mediated single-strand DNA annealing, which we term “Restricted Access Two-Step” ssDNA annealing (RATS). The structure of DdrB–ssDNA confirms earlier predictions that single-strand annealing proteins such as DdrB and Rad52 are able to bind ssDNA in an extended state along one continuous surface of a protein oligomeric ring that ensures strands are presented free of secondary structure in a high-energy state. Unexpectedly, the interaction does not permit equal access of all bases to solvent, but rather systematically buries two out of six bases within each subunit (Fig. 2). This mode of ssDNA binding is not dependent on DNA sequence or degree of strand complementarity, as a structure with entirely altered sequence and less than half the annealing capacity also buried one-third of bound bases (Fig. S1).

In restricted access two-step ssDNA annealing, accurate pairing of strands is achieved using two sequential searches for complementarity. In the first step, DdrB uses an elegant mechanism to limit the search for complementarity to a subset of bound bases. DNA strands initially bound to independent pentamers are brought together to form a transient encounter complex primarily stabilized through weak protein–protein interactions at a stacked pentamer interface. In this complex, only 20 out of 30 bound bases from each strand are permitted access to the opposing strand. When an encounter complex harboring complementary strands is formed, the gain of 20 base pair contacts (Fig. 5A) would be expected to further stabilize pentamer–pentamer association but destabilize pentamer–ssDNA interactions due to increased torsional strain imposed on the sugar phosphate backbone during base pair formation. This is supported by differences in the structure of DNA from encounter complexes with complementary versus noncomplementary strands. B-factors for paired bases are significantly reduced, indicating increased stability. Further studies will be required to determine if the ability to flip out buried bases in the second stage of annealing is the result of increased encounter complex stability and half-life and/or reduced affinity between individual pentamers and single-strand DNA. When full-strand complementarity is achieved between exposed bases within the first step, a second proofreading step is enabled and required to ensure full complementarity. If only the first step was required, misannealing would occur because stable duplex is readily formed with 30-nt strands harboring 1–10 mismatches at biological temperatures. In further support for a second step, it would not have been possible to crystallize an encounter complex in an arrested state with partially annealed DNA if the encounter complex released duplex when only 20 out of 30 bases were complementary. In the second stage of annealing, buried bases have increased opportunity to flip out and sample additional complementarity in the opposing strand. Whether this is the result of increased complex longevity or the result of destabilizing protein–ssDNA interaction remains to be determined. Successful pairing of buried bases, as modeled (Fig. 5B), would result in full complementarity over all 30 bases and the release of highly stable B-form DNA that is unable to rebind DdrB (21). The second proofreading step is made possible not only by restricting access of bound bases, but also by exploiting the limited base-stacking energy available in the extended configuration of bound ssDNA. In the extended conformation, exposed bases within the encounter complex do not stack optimally and therefore have significantly reduced base-stacking interactions relative to B-form DNA. Thus, flipping a noncomplementary base out of a buried position (i.e., where it is better stabilized by interactions with residues such as Y125) (Fig. 5D) would result in an unfavorable, high-energy transition. Under these conditions, noncomplementary bases would remain buried, and the search for complementarity would continue (Fig. 5E). The need for a second proofreading step is best demonstrated by the effect Y125A substitution has on annealing fidelity. Premature release of even one of the two buried bases from DdrB permits significantly higher levels of annealing with noncomplementary strands.

Fig. 5.

DdrB-mediated ssDNA annealing. A face-to-face arrangement of DdrB nucleoprotein complexes facilitates the search for homology between two strands of ssDNA. (A) Base-pairing interactions between exposed bases transiently stabilize the complex, and the buried bases (associated with L87, L97, and Y125) sample the opposing strand for complementarity. (B) Accurate pairing of buried bases, as modeled, results in release of the bound DNA (C). (D) Mispairing of buried bases, as modeled, results in a continuation of the search for homology or dissociation of the decameric complex with DNA still bound to DdrB (E).

A Mechanism for Single-Strand Annealing

The structure of the DdrB–ssDNA complex shares several key features with other DNA and RNA single-strand annealing proteins despite these proteins not being true homologs. Of note, Rad52 (16, 17), Redβ (12), Erf (22), RecT (23), Sak (24), ICP8 (14), and Hfq (25) assemble into multisubunit ring structures similar to DdrB. Conservation of ring structures among single-strand annealing proteins, despite a lack of sequence or structural similarity, is likely the result of convergent evolution. Multisubunit ring structures represent a simple way of forming discretely sized (20–30 bases) nucleic acid-binding interfaces that permit association of nucleic acid strands in a high-energy state free of secondary structure. Another ssDNA-binding protein, ICP8 (14), is thought to form face-to-face arrangements of stacked ring structures in which DNA strands are presented at the interface. In the case of ICP8, an electron microscopy reconstruction clearly illustrates a face-to-face orientation of oligomeric rings that is ssDNA-dependent; however, because of limited resolution, the EM structure could not inform definitively on the position of DNA or the detailed mechanism of strand annealing (14). The structure of Rad52 is not compatible with a stacked face-to-face complex and may involve a distinct mechanism from DdrB for strand annealing. However, without an ssDNA-bound Rad52 structure, it is difficult to say whether some rearrangement of the protein would not occur, promoting a face-to-face complex. Similar questions remain for how small noncoding regulatory RNAs are annealed with transencoded target mRNAs by the ring structure of Hfq. Hfq, a well-characterized member of the Hfq–Sm–LSm protein family (26), has been crystallized in complex with ssRNA (25). In this structure, ssRNA is bound along a continuous surface of a hexameric Hfq ring, with each monomer positioning two bases inward and one outward. Although the precise mechanisms are likely to differ on the basis of biological function, it will be interesting to see whether it is possible to trap an Hfq encounter complex with partially annealed RNA duplex and whether annealing proceeds through a staged annealing mechanism similar to DNA annealing.

The structure of encounter complexes bound to noncomplementary and cDNA strands presented here provides high-resolution insight into a mechanism of ssDNA annealing. Findings are consistent with previous observations from other SSA proteins, such as ICP8, and reveal how cells can use a multistep annealing mechanism involving restricted access of bound bases to overcome the difficult challenge of protecting single-strand DNA from degradation and secondary structure formation and at the same time promote single-strand annealing.

Experimental Procedures

Crystallization.

DdrB1–144 from D. radiodurans was expressed and purified as reported previously (21). Crystals were grown by the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method. Briefly, 1 µL of DdrB1–144/ssDNA (480 µM protein, 143 µM DNA) was mixed with 1 µL of crystallization condition [6% (wt/vol) PEG 2000, 0.1 M Hepes pH 6.5, 0.05 M CaCl2] and 0.2 µL of Hampton Additive Screen condition 48 (0.01 M l-Glutathione reduced, 0.01 M l-Glutathione oxidized) and equilibrated over 1.2 M ammonium sulfate at 20 °C. No additional cryoprotectant was required for data collection. Diffraction data were collected at a wavelength of 1.1 Å on beamline ×25 at the National Synchrotron Light Source at Brookhaven National Laboratory. Decameric DdrB–ssDNA complex formed before crystallization.

Structure Solution.

The diffraction data were integrated with mosflm (27) and then scaled, merged, and converted to structure factors with CCP4 (28, 29). Structure solution was performed with AutoMR from the Phenix software package (30) using the DdrB1–144 monomer from D. radiodurans (PDBID 4HQB) as a search model. The best molecular replacement solution was generated using a search model with manually truncated loops regions, which was then rebuilt-in-place into a simulated annealing OMIT map using Phenix-AutoBuild. Missing loop regions (87–101 and 105–125) and DNA bases were placed manually and refined in iterative cycles using Coot (31) and Phenix-Refine until R and Rfree values converged and geometry statistics reached suitable ranges (Table S1). Validation of the final structure using Ramachandran analysis indicated that 99.1% of amino acids fell within favored positions (0% outliers).

DNA Substrates.

DNA substrates used in crystallography and annealing assays were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. The substrate used to generate cocrystals containing a ss/dsDNA hybrid consisted of a single oligonucleotide (5′-TTGCGCTTGCGCTTGCGCTTGCGCTTGCGC). The 6FAM labeled 60-base probe (5′- ACACTGAGTTTCGTCACCAGTACAAACTACAACGCCTGTAGCATTCCACAGACAGCCCTC) is complementary to a region of M13mp18, whereas substrates 12x (5′-ACACTGAGTTTTGTCACCAGTACGAACTACAACGCTTGTAGCATTCCGCAGACAGCCCTT) and 6x (5′-ACACTAAGTTTTGTCACTAGTACGAACTATAACGCTTGTAGTATTCCGCAGACGGCCCTT) are complementary to the same region with one mismatch every 12 or 6 bases, respectively.

Annealing Assay.

DdrB mutants (K102A and Y125A) were generated by site-directed mutagenesis of the WT expression vector (pPROEX-HT_DR0070) and were purified as previously described (15). Single-strand DNA annealing activity of DdrB was assessed using a 60-base 5′-6FAM labeled probe (5 nM) complementary to a region of M13mp18 (1 nM). Annealing reactions (25 µL) were carried out at 32 °C in annealing buffer [50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 25 mM Mg(CH3COO)2, 1 mM DTT, 5% (vol/vol) glycerol] and were initiated by the addition of the 60-base probe (1.25 µL of 100 nM). Reactions were quenched with 2.5 µL of 2.5 µM unlabeled oligomer in 5% (wt/vol) SDS and resolved using a 1% agarose gel run in TBE buffer (90 mM Tris-borate pH 8.3, 2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) at 50 V. Annealing reaction products were quantified with a GE Amersham Typhoon Trio+ variable-mode imager and ImageJ (32) and were assessed relative to a controlled annealing reaction carried out in a thermocycler in the absence of protein.

Acknowledgments

We thank Annie Héroux for her technical assistance in the collection of structural data on beamline X25 at the National Synchrotron Light Source, Brookhaven National Laboratories. We also thank Chris Brown for editorial comments during the preparation of the manuscript. This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada through Grant 2008R00075 (to M.S.J.) and a studentship (to Y.M.W.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: Crystallography, atomic coordinates, and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 4NOE).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1520847113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Pestryakov PE, Lavrik OI. Mechanisms of single-stranded DNA-binding protein functioning in cellular DNA metabolism. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2008;73(13):1388–1404. doi: 10.1134/s0006297908130026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Battista JR. Against all odds: The survival strategies of Deinococcus radiodurans. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1997;51:203–224. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daly MJ, Minton KW. An alternative pathway of recombination of chromosomal fragments precedes recA-dependent recombination in the radioresistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans. J Bacteriol. 1996;178(15):4461–4471. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4461-4471.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slade D, Lindner AB, Paul G, Radman M. Recombination and replication in DNA repair of heavily irradiated Deinococcus radiodurans. Cell. 2009;136(6):1044–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu G, et al. DdrB stimulates single-stranded DNA annealing and facilitates RecA-independent DNA repair in Deinococcus radiodurans. DNA Repair (Amst) 2010;9(7):805–812. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouthier de la Tour C, et al. The deinococcal DdrB protein is involved in an early step of DNA double strand break repair and in plasmid transformation through its single-strand annealing activity. DNA Repair (Amst) 2011;10(12):1223–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Y, et al. Transcriptome dynamics of Deinococcus radiodurans recovering from ionizing radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(7):4191–4196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630387100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka M, et al. Analysis of Deinococcus radiodurans’s transcriptional response to ionizing radiation and desiccation reveals novel proteins that contribute to extreme radioresistance. Genetics. 2004;168(1):21–33. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.029249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norais CA, Chitteni-Pattu S, Wood EA, Inman RB, Cox MM. DdrB protein, an alternative Deinococcus radiodurans SSB induced by ionizing radiation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(32):21402–21411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.010454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lockhart JS, DeVeaux LC. The essential role of the Deinococcus radiodurans ssb gene in cell survival and radiation tolerance. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71651. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iyer LM, Koonin EV, Aravind L. Classification and evolutionary history of the single-strand annealing proteins, RecT, Redbeta, ERF and RAD52. BMC Genomics. 2002;3:8–18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-3-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Passy SI, Yu X, Li Z, Radding CM, Egelman EH. Rings and filaments of beta protein from bacteriophage lambda suggest a superfamily of recombination proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(8):4279–4284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erler A, et al. Conformational adaptability of Redbeta during DNA annealing and implications for its structural relationship with Rad52. J Mol Biol. 2009;391(3):586–598. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tolun G, Makhov AM, Ludtke SJ, Griffith JD. Details of ssDNA annealing revealed by an HSV-1 ICP8-ssDNA binary complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(11):5927–5937. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugiman-Marangos SN, Peel JK, Weiss YM, Ghirlando R, Junop MS. Crystal structure of the DdrB/ssDNA complex from Deinococcus radiodurans reveals a DNA binding surface involving higher-order oligomeric states. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(21):9934–9944. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singleton MR, Wentzell LM, Liu Y, West SC, Wigley DB. Structure of the single-strand annealing domain of human RAD52 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(21):13492–13497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212449899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kagawa W, et al. Crystal structure of the homologous-pairing domain from the human Rad52 recombinase in the undecameric form. Mol Cell. 2002;10(2):359–371. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00587-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grimme JM, et al. Human Rad52 binds and wraps single-stranded DNA and mediates annealing via two hRad52-ssDNA complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(9):2917–2930. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parsons CA, Baumann P, Van Dyck E, West SC. Precise binding of single-stranded DNA termini by human RAD52 protein. EMBO J. 2000;19(15):4175–4181. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.15.4175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lloyd JA, Forget AL, Knight KL. Correlation of biochemical properties with the oligomeric state of human rad52 protein. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(48):46172–46178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207262200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugiman-Marangos S, Junop MS. The structure of DdrB from Deinococcus: A new fold for single-stranded DNA binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(10):3432–3440. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poteete AR, Sauer RT, Hendrix RW. Domain structure and quaternary organization of the bacteriophage P22 Erf protein. J Mol Biol. 1983;171(4):401–418. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(83)90037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thresher RJ, Makhov AM, Hall SD, Kolodner R, Griffith JD. Electron microscopic visualization of RecT protein and its complexes with DNA. J Mol Biol. 1995;254(3):364–371. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ploquin M, et al. Functional and structural basis for a bacteriophage homolog of human RAD52. Curr Biol. 2008;18(15):1142–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.06.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Link TM, Valentin-Hansen P, Brennan RG. Structure of Escherichia coli Hfq bound to polyriboadenylate RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(46):19292–19297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908744106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vogel J, Luisi BF. Hfq and its constellation of RNA. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9(8):578–589. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leslie GWA, Powell HR. Processing diffraction data with mosflm. Evolving Methods for Macromolecular Crystallography. 2007;245:41–51. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67(Pt 4):235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.French S, Wilson K. On the treatment of negative intensity observations. Acta Crystallogr A. 1978;34(4):517–525. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 2):213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60(12):2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9(7):671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]