Abstract

Purpose

Although reported success rates after pediatric pyeloplasty to correct ureteropelvic junction are high, failure may require intervention. We sought to characterize the incidence and timing of secondary procedures after pediatric pyeloplasty using a national employer based insurance database.

Materials and Methods

Using the MarketScan® database we identified patients 0 to 18 years old who underwent pyeloplasty from 2007 to 2013 with greater than 3 months of postoperative enrollment. Secondary procedures following the index pyeloplasty were identified by CPT codes and classified as stent/drain, endoscopic, pyeloplasty, nephrectomy or transplant. The risk of undergoing a secondary procedure was ascertained using Cox proportional hazards models adjusting for demographic and clinical characteristics.

Results

We identified 1,976 patients with a mean ± SD followup of 23.9 ± 19.8 months. Overall 226 children (11.4%) had undergone at least 1 post-pyeloplasty procedure. The first procedure was done within 1 year in 87.2% of patients with a mean postoperative interval of 5.9 ± 11.1 months. Stents/drains, endoscopic procedures and pyeloplasties were noted in 116 (5.9%), 34 (1.7%) and 71 patients (3.1%), respectively. Length of stay was associated with undergoing a secondary procedure. Compared with 2 days or less the HR of 3 to 5 and 6 days or greater was 1.65 and 3.94 (p = 0.001 and <0.001, respectively).

Conclusions

Following pediatric pyeloplasty 1 of 9 patients undergoes at least 1 secondary procedure with the majority performed within the first year. One of 11 patients undergoes intervention more extensive than placement of a single stent or drain, requiring management strategies that generally signify recurrent or persistent obstruction. Estimates of pyeloplasty success in this national data set are lower than in other published series.

Keywords: kidney, hydronephrosis, ureteral obstruction, treatment failure, minimally invasive surgical procedures

Pyeloplasty remains the gold standard management of UPJ obstruction in children with success rates greater than 94% reported across open, laparoscopic and robotic assisted approaches in recent series.1–6 However, these data were derived predominantly from single or multi-institutional experiences at high volume academic centers. In addition, although a favorable result is defined by a combination of clinical and radiographic criteria, imaging followup to determine success after pyeloplasty is inconsistent. In a recent study using MarketScan data almost 6% of pediatric patients underwent no imaging after pyeloplasty and a third were not monitored radiographically beyond 1 year.7 It can be assumed that lack of imaging mirrors lack of clinical followup and, thus, insufficient followup may bias estimates of pyeloplasty success.

One indicator of success after pyeloplasty is freedom from additional surgery or secondary procedures. Although the rate of secondary procedures for obstruction underestimates pyeloplasty success if one considers undiagnosed silent failures, this incidence may serve as an objective, reportable measure of failure.

In this study we aimed to characterize the incidence, type and timing of secondary procedures after pediatric pyeloplasty using a national employer based insurance database and determine factors that may contribute to the likelihood of undergoing secondary procedures. We hypothesized that the secondary procedure rate following index pyeloplasty would be higher than reported in the literature, and comorbidities and LOS would be associated with increased secondary procedure rates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Source

MarketScan contains information from employer based commercial health plans in the United States, including records captured longitudinally from inpatient and outpatient encounters.8 De-identified individual health service records comprise patient demographics, service dates, LOS, and ICD-9-CM and CPT codes. The data set contains approximately 60 million inpatient records, representing approximately 50% of annual discharges from American hospitals. Race/ethnicity and socioeconomic data are unavailable.

Study Population

We identified patients 0 to 18 years old who underwent pyeloplasty from 2007 to 2013. We used CPT codes for simple, complicated and laparoscopic pyeloplasty and ureteropyelostomy, and ICD-9 codes for correction of UPJ, which we defined as the index pyeloplasty. The supplementary Appendix (http://jurology.com/) lists abstracted diagnosis and procedure codes. While it is possible that some index pyeloplasties were redo procedures if the true index procedure occurred before 2007, this chance of misclassification was expected to be low, given the low incidence of redo pyeloplasty. Unless a secondary procedure was performed within 3 months after pyeloplasty we excluded from analysis patients with greater than 3 months of postoperative enrollment in MarketScan so that insurance coverage was maintained postoperatively. This criterion was applied to ensure that if there was a lack of additional detected procedures, it was not due to change in insurance status.

Patient and Hospital Characteristics

Characteristics evaluated included age at surgery, gender, number of comorbidities, MIP, year of surgery, hospital region, urban status, insurance status (HMO or nonHMO) and LOS. Age was divided into categories of 0 to 2, 3 to 6, 7 to 13 and 14 to 18 years based on NIH (National Institutes of Health) categories. LOS was divided into categories of 1 to 2, 3 to 5 and 6 or more days.

CPT and ICD-9-CM codes were used to identify procedural interventions following initial pyeloplasty hospitalization during distinct postoperative encounters. The secondary procedure categories were stents/drains, including nephrostomy placement; endoscopic correction, including balloon ureteral dilation, and antegrade and retrograde endopyelotomy; repeat pyeloplasty; nephrectomy; and renal transplant. Ureteral stent removal as the first postoperative procedure was considered an indicator of intraoperative stent use and evaluated separately from the other procedures as an expected postoperative event. When patients had multiple codes corresponding to a single encounter, only the most invasive procedure was counted. For instance endopyelotomy with stent placement was counted as endoscopic management rather than as stent/drain. Repeat stent exchanges were counted as a single stent/drain management strategy. Time to first occurrence of each secondary procedure was assessed.

Statistical Analysis

Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to determine risk factors associated with secondary procedures. These risk factors included MIP, age, gender, LOS and comorbidities. Kaplan-Meier curves were generated to illustrate the likelihood of secondary procedure with time by LOS categories. Time to event was defined as time from the index pyeloplasty to the first unplanned secondary procedure. Subjects without an event were censored at loss of MarketScan enrollment or at the end of 2013. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata® 12.1 with 2-sided p <0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 1,976 patients were identified with a mean ± SD followup of 23.9 ± 19.8 months (median 17.9, range 1 to 83.6). Table 1 lists patient demographics. MIP was done in 161 index cases (31%) and in 18 redo pyeloplasties (25%). From 2007 to 2013 the percent of MIPs increased from 16.4% to 42.3% of index cases. It rose from 0 of 4 (0%) to 5 of 14 (35.7%) redo pyeloplasties, although yearly redo case numbers were small. Stent removal after pyeloplasty was coded in 797 patients (40.3%).

Table 1.

Demographics of 1,976 patients and univariate association with unanticipated secondary procedures

| No. Secondary Procedure (%)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Univarate p Value (chi-square) | |

| Age (yrs): | 0.142 | ||

| 0–2 | 778 (89) | 96 (11) | |

| 3–6 | 294 (91) | 29 (9) | |

| 7–13 | 358 (88) | 47 (12) | |

| 14–18 | 320 (86) | 54 (11) | |

| Gender: | 0.674 | ||

| Male | 1,168 (88) | 154 (12) | |

| Female | 582 (89) | 72 (11) | |

| No. comorbidities: | |||

| 0 | 1,795 (90) | 204 (10) | |

| 1 or More | 162 (88) | 22 (12) | |

| Operative approach: | 0.488 | ||

| Open | 1,209 (89) | 151 (11) | |

| Minimally invasive | 541 (88) | 75 (12) | |

| Surgery yr: | |||

| 2007 | 194 (88) | 26 (12) | |

| 2008 | 268 (85) | 47 (15) | |

| 2009 | 288 (89) | 36 (11) | |

| 2010 | 272 (85) | 48 (15) | |

| 2011 | 280 (90) | 32 (10) | |

| 2012 | 267 (92) | 22 (8) | |

| 2013 | 181 (92) | 15 (8) | |

| Region: | 0.483 | ||

| Northeast | 302 (86) | 49 (14) | |

| North central | 496 (90) | 56 (10) | |

| South | 548 (89) | 69 (11) | |

| West | 353 (89) | 44 (11) | |

| Unknown | 51 (86) | 8 (14) | |

| Urban: | |||

| Yes | 1,492 (89) | 192 (11) | |

| No | 258 (88) | 34 (12) | |

| HMO status: | |||

| Yes | 369 (87) | 56 (13) | 0.204 |

| No | 1,381 (89) | 170 (11) | |

| LOS (days): | <0.001 | ||

| 1–2 | 1,370 (90) | 145 (10) | |

| 3–5 | 344 (85) | 63 (15) | |

| 6 or Greater | 36 (67) | 18 (33) | |

Overall 226 children (11.4%) underwent at least 1 unplanned secondary procedure after index pyeloplasty. The first postoperative procedure was done within 1 year of surgery in 87.2% of patients, between 1 and 2 years in 8.4% and after 2 years in 4.4% (fig. 1). Mean time to the first postoperative procedure was 5.9 ± 11.1 months. Management included a stent/drain, endoscopic procedure and redo pyeloplasty in 116 (5.9%), 34 (1.7%) and 71 (3.6%) patients, respectively, with nephrectomy in 4 and transplantation in 1 (table 2).

Figure 1.

Time to first secondary procedure after index pyeloplasty

Table 2.

Time to most invasive secondary procedure type after pyeloplasty

| No. Pts | Mean ± SD Mos Since Initial Procedure (range) | |

|---|---|---|

| Any | 226 | 6.0 ± 11.2 (0–70.4) |

| Stent/drain | 116 | 5.5 ± 11.1 (0–70.4) |

| Endoscopic | 34 | 6.6 ± 8.5 (0.4–50.3) |

| Pyeloplasty | 71 | 10.2 ± 10.7 (0–54.4) |

| Nephrectomy | 4 | 7.5 ± 3.1 (5.3–12.1) |

| Transplantation | 1 | 12.1 |

Of the 191 patients who received a stent/drain postoperatively regardless of additional procedures 28 underwent 2 stent/drain placement only. Mean time to a stent/drain was 5.5 ± 11.1 months and mean followup after a second stent/drain placement was 21.7 ± 16.8 months with no additional secondary procedures.

Secondary endoscopic procedures were performed in 41 patients, of whom 5 subsequently underwent redo pyeloplasty, 1 underwent an endoscopic procedure after redo pyeloplasty and 1 was treated with the endoscopic procedure prior to nephrectomy. Of these patients 36.6% underwent stent placement before endoscopic management. Eight endoscopic procedures (19.5%) were done in the 0 to 2-year-old group while 4 (9.8%), 10 (24.4%), 16 (39%) and 3 (7.3%) were done at ages 3 to 6, 7 to 13, 14 to 18 and greater than 18 years, respectively.

Of the 71 patients who underwent redo pyeloplasty 39 (54.9%) did so directly while 25 (36.6%) received a stent/drain first. One patient received a stent/drain and then 2 redo pyeloplasties. Of patients treated with nephrectomy 1 had an initial stent/drain, 1 had a stent/drain and then underwent an endoscopic procedure and 2 proceeded immediately to nephrectomy. The patient who required a renal transplant underwent no interval procedure. At initial pyeloplasty in nephrectomy and transplant cases there were no comorbidities or concomitant procedures such as nephrolithotomy to explain the dire outcomes. There was no difference in the secondary procedure rate between those who had a stent intraoperatively during index pyeloplasty and those who were unstented (11.7% vs 11.0%, p = 0.85).

Sensitivity analysis was performed, excluding patients with less than 12 months of postoperative enrollment. Reinforcing our findings, 12.6% of patients underwent a secondary procedure, including stent/drain placement in 10.5%, endopyelotomy in 2.5%, redo pyeloplasty in 4.3%, nephrectomy in 2 and transplantation in 1.

We attempted to distinguish patients who received a stent/drain for similarly managed complications such as ureteral edema, urine leak or urinoma rather than persistent or recurrent obstruction. Of 116 patients who underwent only stent/drain placement 44 (37.9%) had a single postoperative stent/drain and no further procedure. The remaining 72 patients (62.1%) received 2 or more stent/drains while 1 patient underwent 14 stent/drain procedures during followup. Excluding those with only 1 postoperative stent/drain the secondary procedure rate was 9.2% (182 cases).

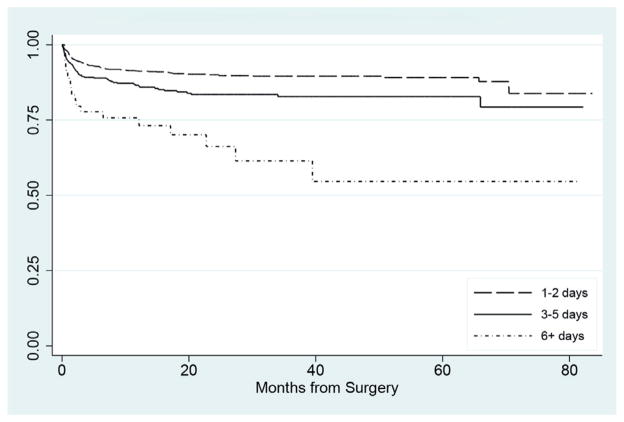

On univariate and multivariate analysis patient age, gender, year of surgery, geographic region, urban vs rural status, HMO insurance status and minimally invasive technique were not associated with an unanticipated secondary procedure (table 3). Longer LOS after index pyeloplasty was significantly associated with an increased risk of an unanticipated post-pyeloplasty procedure. Compared with 2 or fewer days the HR for 3 to 5 and 6 days or greater was 1.65 and 3.94, respectively (p = 0.001 and <0.001, fig. 2).

Table 3.

Proportional hazards regression model of association of demographic factors with secondary procedure after pyeloplasty

| Characteristic | No. Pts | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs): | ||

| 0–2 | 874 | Referent |

| 3–6 | 323 | 0.74 (0.48–1.13) |

| 7–13 | 405 | 0.93 (0.64–1.35) |

| 14–18 | 374 | 1.19 (0.80–1.77) |

| Gender: | ||

| Male | 1,322 | Referent |

| Female | 654 | 0.90 (0.68–1.19) |

| Minimally invasive approach: | ||

| No | 1,360 | Referent |

| Yes | 616 | 1.11 (0.80–1.55) |

| LOS (days): | ||

| 1–2 | 1,515 | Referent |

| 3–5 | 407 | 1.65 (1.22–2.24)* |

| 6 or Greater | 54 | 3.94 (2.41–6.46)* |

Significant (p <0.05).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve of likelihood of undergoing secondary procedure based on index pyeloplasty LOS.

DISCUSSION

There are several notable findings of this study. 1) One of 9 pediatric patients treated with pyeloplasty required a secondary procedure and 1 in 11 required procedures more extensive than a single stent or drain. Although most secondary procedures were performed in the first year after surgery, a significant 13% were done after 1 year. 2) Stents/drains were the most common secondary procedures followed by redo pyeloplasty and endoscopic management with a small number of patients requiring nephrectomy or transplantation. MIP rates in index and redo cases increased during the study period. 3) Longer LOS after index pyeloplasty was associated with an increased risk of requiring a secondary procedure on multivariate analysis.

Various factors may contribute to the discrepancy between published pyeloplasty success rates and the 9.2% of patients who underwent greater than 1 stent/drain placement in our population, including bias from insufficient followup imaging in the current literature. There are no established guidelines regarding the ideal surveillance imaging modality, timing or duration after pediatric pyeloplasty. Some groups have suggested that long-term imaging after an unobstructed postoperative functional study is unwarranted.9,10 Accordingly the intensity and type of imaging followup varies widely.7 Of privately insured pediatric patients 5.9% underwent no followup imaging after the index operation and a third were not monitored radiographically beyond 1 year.7

Published reports and our study may underestimate failure rates due to unevaluated silent obstruction and late failures. Symptoms alone are inadequate to guide followup imaging as poor correlation exists between symptoms and radiographic obstruction.10,11 In fact worsening asymptomatic hydronephrosis accounts for a considerable proportion of pyeloplasty failures requiring surgical intervention at a rate higher than 40% in some series.4,12 Late failures can present 8 or more years after primary pyeloplasty.10,12

Publication bias may also influence current understanding of pyeloplasty outcomes as the body of literature on pyeloplasty complications and failures consists mostly of single and multicenter observational studies by groups at higher volume academic institutions.13 In such settings studies with negative findings are less likely to be submitted and published.14 We captured a national sample incorporating community and academic practices that are otherwise underrepresented in the literature, although still not generalizable to the uninsured population. It was reported that pediatric urologists tend to overestimate pyeloplasty case volume and may perceive their success rate to be greater than published rates.15 A review of personal, local and national outcomes would enable providers to most appropriately counsel parents on surgical risk.

Our study provides insight into how frequently various pyeloplasty salvage strategies are used nationwide. Serial stent/drains comprised the majority of secondary procedures. In patients who underwent only 2 stent/drain placements the mean procedure-free interval of 21.7 months following the last stent/drain suggests greater long-term success than previously described for stenting alone.4 Redo pyeloplasty was the next most common secondary procedure. MIP has grown increasingly common in the last 2 decades, accounting for 83% of adult cases in 2011.16 However, patients without private insurance may be less likely to undergo MIP17 and they are not represented in this study. Pediatric and redo pyeloplasties reflect this growing trend and the steady uptake of MIP during our study period mirrors that in prior publications.18,19

Endoscopic management was performed approximately half as frequently as redo pyeloplasty, which remains the gold standard to manage pediatric pyeloplasty failure. Several series have described success rates of 78% to 100% between reoperative MIP and open redo pyeloplasty.12,20–23 Although Kim et al reported a 94% success rate for endoscopic management of failed pyeloplasty in 31 pediatric patients,24 most groups have experienced marginal 20% to 70% success with secondary endopyelotomy.12,25,26 Adults may experience better outcomes from salvage endoscopic procedures with 70% to 87.5% success in some series, which is more acceptable in a population with lower life expectancy.27,28 Although we expected to find endoscopic treatments mostly in older adolescents, reflecting greater acceptance of secondary endopyelotomy in adults, more than half of the endoscopic attempts were performed in patients younger than 14 years.

Due in part to the small sample sizes reported in the literature attempts to identify an etiology of pyeloplasty failure have been unsuccessful. Suggestions of prolonged urinary drainage and uro-sepsis creating an overwhelming local tissue response remain speculative.29 Lack of retrograde pyelogram during the initial procedure was raised as a possibility but it does not appear to be associated with failure rates.30 Earlier theories that younger age (less than 6 months) at initial operation places patients at higher risk29 are unsupported by more recent series4,25 and by our study.

We found that LOS was the only covariate significantly associated with the risk of requiring a secondary procedure. Postoperative hospitalization typically spans 1 or 2 and 2 or 3 nights after MIP and open pyeloplasty, respectively.19 Longer admissions may represent patients who underwent more complex operations or those in whom complications developed such as infection, urine leak, vascular injury or urinoma formation, of which all may contribute to stricture formation. We also believed that longer admission could indicate more severe underlying comorbidities. However, the presence of comorbidities was not associated with undergoing a secondary procedure in this study.

These findings must be interpreted in the context of the limitations of our study design. Use of an administrative data set limited the availability of information regarding preoperative factors, including the severity of underlying hydronephrosis or obstruction, symptoms and laterality, and operative details such as UPJ anatomy and case complexity, which may all impact pyeloplasty success. The CPT code for complicated pyeloplasty (50405) includes congenital kidney abnormality in its definition, which may accurately describe an uncomplicated operation in an infant with congenital UPJ obstruction. Thus, we were unable to use this code to estimate case complexity. There was no difference in the secondary procedure rate or in LOS between patients in whom the index pyeloplasty were coded as complicated vs standard. Coding error, including inaccurate or incomplete coding, may also be present. Finally, an employer based insurance database may limit generalizability of our findings in patients without insurance coverage.

Despite these limitations our data provide broader insight into the percent of pediatric pyeloplasty cases that require unanticipated secondary procedures with a mean followup approaching 2 years in a broader sample than found in the existing literature. This study highlights several deficiencies in the current literature and practices surrounding pediatric pyeloplasty, including the need for consistent recommendations to guide imaging type and followup duration in children following pyeloplasty as well as clearer definitions of failure to suggest when re-intervention is indicated.

CONCLUSIONS

In a nationally representative pediatric population 1 of 9 patients underwent an unplanned secondary procedure following pyeloplasty. One of 11 patients underwent procedures more extensive than receiving a single stent or drain, requiring management strategies that generally signify recurrent or persistent obstruction. This is higher than most published rates of pyeloplasty failure. These discrepancies may reflect publication bias and insufficient radiographic followup. In our study LOS was associated with an increased risk of a secondary procedure and it may be an indicator of perioperative complications. Larger scale, prospective data collection on pyeloplasty outcomes may provide necessary insight to fill gaps in the literature. Our findings yield important information for preoperative patient counseling and informed consent.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- HMO

health maintenance organization

- LOS

length of stay

- MIP

minimally invasive pyeloplasty

- UPJ

ureteropelvic junction

Footnotes

No direct or indirect commercial incentive associated with publishing this article.

The corresponding author certifies that, when applicable, a statement(s) has been included in the manuscript documenting institutional review board, ethics committee or ethical review board study approval; principles of Helsinki Declaration were followed in lieu of formal ethics committee approval; institutional animal care and use committee approval; all human subjects provided written informed consent with guarantees of confidentiality; IRB approved protocol number; animal approved project number.

References

- 1.Autorino R, Eden C, El-Ghoneimi A, et al. Robot-assisted and laparoscopic repair of ureteropelvic junction obstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2014;65:430. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanc T, Muller C, Abdoul H, et al. Retroperitoneal laparoscopic pyeloplasty in children: long-term outcome and critical analysis of 10-year experience in a teaching center. Eur Urol. 2013;63:565. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minnillo BJ, Cruz JA, Sayao RH, et al. Long-term experience and outcomes of robotic assisted laparoscopic pyeloplasty in children and young adults. J Urol. 2011;185:1455. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romao RL, Koyle MA, Pippi Salle JL, et al. Failed pyeloplasty in children: revisiting the unknown. Urology. 2013;82:1145. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helmy TE, Sarhan OM, Hafez AT, et al. Surgical management of failed pyeloplasty in children: single-center experience. J Pediatr Urol. 2009;5:87. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braga LH, Lorenzo AJ, Bagli DJ, et al. Risk factors for recurrent ureteropelvic junction obstruction after open pyeloplasty in a large pediatric cohort. J Urol. 2008;180:1684. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsi RS, Holt SK, Gore JL, et al. National trends in followup imaging after pyeloplasty in children in the United States. J Urol. 2015;194:777. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.03.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albert MA, Danielson E, Rifai N, et al. Health Research Data for the Real World: The MarketScan Database. Ann Arbor: Thomson Medstat; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pohl HG, Rushton HG, Park JS, et al. Early diuresis renogram findings predict success following pyeloplasty. J Urol. 2001;165:2311. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)66192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Psooy K, Pike JG, Leonard MP. Long-term followup of pediatric dismembered pyeloplasty: how long is long enough? J Urol. 2003;169:1809. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000055040.19568.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pouliot F, Lebel MH, Audet JF, et al. Determination of success by objective scintigraphic criteria after laparoscopic pyeloplasty. J Endourol. 2010;24:299. doi: 10.1089/end.2009.0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braga LH, Lorenzo AJ, Skeldon S, et al. Failed pyeloplasty in children: comparative analysis of retrograde endopyelotomy versus redo pyeloplasty. J Urol. 2007;178:2571. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Easterbrook PJ, Berlin JA, Gopalan R, et al. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet. 1991;337:867. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90201-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hopewell S, Loudon K, Clarke MJ, et al. Publication bias in clinical trials due to statistical significance or direction of trial results. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:MR000006. doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000006.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prasad MM, Marks A, Vasquez E, et al. Published surgical success rates in pediatric urology—fact or fiction? J Urol. 2012;188:1643. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oberlin DT, McGuire BB, Pilecki M, et al. Contemporary national surgical outcomes in the treatment of ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Urology. 2015;85:363. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.07.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sukumar S, Sun M, Karakiewicz PI, et al. National trends and disparities in the use of minimally invasive adult pyeloplasty. J Urol. 2012;188:913. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vemulakonda VM, Cowan CA, Lendvay TS, et al. Surgical management of congenital ureteropelvic junction obstruction: a Pediatric Health Information System database study. J Urol. 2008;180:1689. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varda BK, Johnson EK, Clark C, et al. National trends of perioperative outcomes and costs for open, laparoscopic and robotic pediatric pyeloplasty. J Urol. 2014;191:1090. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.10.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asensio M, Gander R, Royo GF, et al. Failed pyeloplasty in children: is robot-assisted laparoscopic reoperative repair feasible? J Pediatr Urol. 2015;11:69, e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindgren BW, Hagerty J, Meyer T, et al. Robot-assisted laparoscopic reoperative repair for failed pyeloplasty in children: a safe and highly effective treatment option. J Urol. 2012;188:932. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.04.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piaggio LA, Noh PH, Gonzalez R. Reoperative laparoscopic pyeloplasty in children: comparison with open surgery. J Urol. 2007;177:1878. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thom MR, Haseebuddin M, Roytman TM, et al. Robot-assisted pyeloplasty: outcomes for primary and secondary repairs, a single institution experience. Int Braz J Urol. 2012;38:77. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382012000100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim EH, Tanagho YS, Traxel EJ, et al. Endopyelotomy for pediatric ureteropelvic junction obstruction: a review of our 25-year experience. J Urol. 2012;188:1628. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas JC, DeMarco RT, Donohoe JM, et al. Management of the failed pyeloplasty: a contemporary review. J Urol. 2005;174:2363. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000180420.11915.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veenboer PW, Chrzan R, Dik P, et al. Secondary endoscopic pyelotomy in children with failed pyeloplasty. Urology. 2011;77:1450. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jabbour ME, Goldfischer ER, Klima WJ, et al. Endopyelotomy after failed pyeloplasty: the long-term results. J Urol. 1998;160:690. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)62757-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park J, Kim WS, Hong B, et al. Long-term outcome of secondary endopyelotomy after failed primary intervention for ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Int J Urol. 2008;15:490. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2008.02035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lim DJ, Walker RD., 3rd Management of the failed pyeloplasty. J Urol. 1996;156:738. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199608001-00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rushton HG, Salem Y, Belman AB, et al. Pediatric pyeloplasty: is routine retrograde pyelography necessary? J Urol. 1994;152:604. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32661-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.