Abstract

Dense fibrosis and a robust macrophage infiltrate are key therapeutic barriers in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). CD40 activation can circumvent these barriers by inducing macrophages, originating from peripheral blood monocytes, to deplete fibrosis. The precise mechanism and therapeutic implications of this anti-fibrotic activity, though, remain unclear. Here, we report that IFN-γ and CCL2 released systemically in response to a CD40 agonist cooperate to redirect a subset of Ly6C+CCR2+ monocytes/macrophages to infiltrate tumors and deplete fibrosis. Whereas CCL2 is required for Ly6C+ monocyte/macrophage infiltration, IFN-γ is necessary for tumor-infiltrating monocytes/macrophages to shift the profile of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in tumors leading to MMP-dependent fibrosis degradation. In addition, MMP13-dependent loss of extracellular matrix components induced by a CD40 agonist increased PDAC sensitivity to chemotherapy. Our findings demonstrate that fibrosis in PDAC is a bidirectional process that can be rapidly altered by manipulating a subset of tumor-infiltrating monocytes leading to enhanced chemotherapy efficacy.

Keywords: Monocyte, CCL2, IFN-γ, fibrosis, pancreatic carcinoma

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is currently the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States (1). With an overall five-year survival of only six percent, PDAC has demonstrated unusual resistance to standard therapies including chemotherapy, immunotherapy and radiation (2). A hallmark of PDAC is a formidable tumor microenvironment marked by extensive fibrosis and a robust cellular infiltrate comprised of activated fibroblasts and immunosuppressive leukocyte populations including macrophages and regulatory T cells (3, 4). This desmoplastic reaction has been recognized as a major barrier to drug delivery and the productivity of immunotherapy (5-7). As a result, the tumor microenvironment has emerged as a promising therapeutic target in PDAC. However, the cellular and molecular mechanisms that regulate this microenvironment are still being elucidated. Whereas genetically disrupting key elements of desmoplasia can have deleterious consequences (8, 9), immunotherapeutic strategies that target cancer fibrosis have shown benefit in both mice and humans (10-12). Given these disparate outcomes with targeting desmoplasia in PDAC, an understanding of the in vivo mechanisms that regulate the tumor microenvironment is critical.

Tumor-infiltrating macrophages are commonly found associated with cancer fibrosis (13, 14) and frequently predict a poor prognosis (15, 16). These macrophages derive from inflammatory (or classical) monocytes and are well-described proponents of tumor development, growth, and metastasis (17-19). In non-malignant disorders, monocytes can be key regulators of both the development and resolution of fibrosis (20-22). In the context of cancer however, macrophages are involved in extracellular matrix remodeling and act as promoters of cancer fibrosis (18, 23-25). The phenotype of macrophages, though, is dependent on signals received from their surrounding microenvironment. Consistent with this premise, we have previously demonstrated that systemic delivery of a CD40 agonist stimulates macrophages originating from peripheral blood monocytes to facilitate the depletion of extracellular matrix proteins and induce tumor regressions in both mice and patients with PDAC (11). This anti-tumor effect occurred independent of T cells despite the well-established role of CD40, a member of the TNF receptor superfamily, in the development of T cell-dependent anti-tumor immunity (26-28). However, the mechanism by which a CD40 agonist redirects monocytes with anti-fibrotic properties in vivo has remained elusive. In this report, we studied the KPC mouse model of PDAC which incorporates the expression of KrasG12D and Trp53R172H alleles targeted to the pancreas using Cre recombinase driven by the Pdx-1 promoter (29). Using this model, we investigated the mechanism by which monocytes deplete fibrosis in PDAC and found that this biology has important therapeutic implications.

Results

CD40 agonists induce a subset of monocytes to infiltrate PDAC

CD40-dependent anti-fibrotic activity is dependent on monocytes/macrophages and does not require T cells (11). Therefore, to address the mechanism of CD40-dependent anti-fibrotic activity in PDAC, we first characterized monocytes in the peripheral blood of KPC mice. Using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), mouse monocytes were identified by their expression of F4/80 and separated into sub-populations of resident (or non-classical) monocytes which lack expression of Gr-1 (Ly6C/Ly6G) and inflammatory (or classical) monocytes which express Gr-1 and Ly6C but not Ly6G (Supplementary Figure S1A-B). Unlike Gr-1neg resident monocytes, Gr-1+ inflammatory monocytes also uniquely express the chemokine receptor, CCR2 (Supplementary Figure S1A-B). Accordingly, we found that inflammatory monocytes were increased in the peripheral blood of KPC mice compared to normal littermates (Figure 1A). This finding is consistent with observations in human PDAC patients showing increased peripheral blood mobilization of inflammatory monocytes (30).

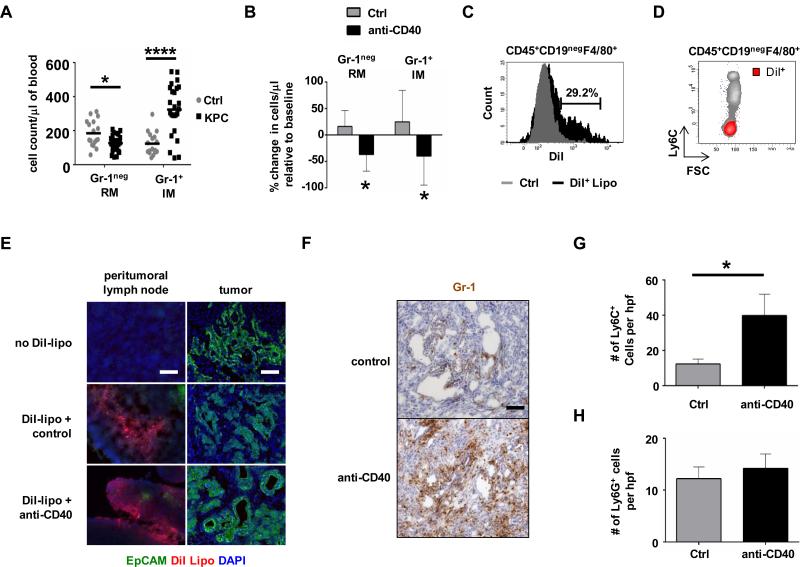

Figure 1. Monocyte subsets show distinct trafficking patterns in response to agonist CD40 therapy in KPC mice.

(A) Peripheral blood counts for F4/80+Gr-1neg resident monocytes (RM) and F4/80+Gr-1+ inflammatory monocytes (IM) in control (Ctrl) littermates and tumor-bearing KPC mice. Bar shows mean; n=17-25 per group, *, P<0.05; ****, P<0.0001. (B) Percent change in monocyte subsets within blood of KPC mice one day after treatment. n=4-7 per group, *, P<0.05. (C) KPC mice were treated with unlabeled liposomes (Ctrl) versus DiI-labeled liposomes (DiI+ Lipo) and blood was analyzed 24 hours later. Shown is a representative histogram of CD45+CD19negF4/80+ monocytes labeled with DiI-liposomes in vivo. (D) Representative FACS plot showing relationship between labeling with DiI-liposomes in vivo and Ly6C expression to identify subsets of CD45+CD19negF4/80+ monocytes. (E) KPC mice were injected i.p. with DiI-labeled liposomes one hour before treatment with istoype control or anti-CD40 antibodies. Tumor tissue was analyzed 48 hours later. Shown is immunofluorescence imaging of peritumoral lymph nodes and tumor to detect monocyte/macrophages labeled with DiI-labeled liposomes (red) and EpCAM+ tumor cells (green). n=3 mice. One representative image of three is shown per group. Scale bar, 100 μm. (F) Representative images of anti-Gr-1 stained tumor tissue from KPC mice one day after treatment. Scale bar, 100 μm. Quantification of (G) Ly6C+ myeloid cells (n=4-5 mice per group) and (H) Ly6G+ cells (n≥3 mice group) within tumor tissue of KPC mice one day after treatment. *, P<0.05, unpaired 2-tailed t-test.

We next examined the impact of treatment with an agonist CD40 antibody on inflammatory and resident monocyte subsets within the peripheral blood and found that both monocyte populations rapidly decreased within hours after anti-CD40 treatment (Figure 1B). To track the migration of monocytes into tissues in response to anti-CD40 therapy, we used fluorescently-tagged liposomes to label monocytes in vivo. This was possible because liposomes cannot traverse vascular boundaries and therefore, do not directly target myeloid cell populations within the tumor microenvironment (11, 31). We found that liposomes specifically targeted F4/80+ resident monocytes, which lack expression of Ly6C, and not F4/80+Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes within the peripheral blood (Figure 1, C and D). Using this liposomal approach to label resident monocytes in vivo, we determined that resident and inflammatory monocytes displayed distinct migration patterns in response to CD40 therapy. Specifically, resident monocytes did not infiltrate tumor tissue after anti-CD40 treatment (Figure 1E) but could be detected within peritumoral lymph nodes (Figure 1E) and were found to accumulate in the spleen (Supplementary Figure S2A-B). In contrast, we observed a rapid infiltration of tumors by Gr-1+ cells within 18 hours after anti-CD40 treatment (Figure 1F). Because Gr-1 is a composite epitope of Ly6C and Ly6G and thus expressed by both Ly6C+ myeloid cells and Ly6G+ granulocytes, we next examined tumor tissue for the presence of each of these cellular populations. We found an increase in Ly6C+ macrophages in PDAC tumors (Figure 1G) but detected no difference in the number of tumor-infiltrating Ly6G+ granulocytes (Figure 1H, Supplementary Figure S3). From these findings, we concluded that a CD40 agonist induces the trafficking of Ly6Chi inflammatory monocytes out of the peripheral blood with a corresponding infiltration of Ly6C+ macrophages into PDAC tumors.

Resident monocytes/macrophages coordinate CCL2-dependent inflammatory monocyte/macrophage infiltration into PDAC tumors

The finding that resident monocytes targeted by liposomes do not infiltrate the tumor microenvironment was unexpected based on our previous observation that clodronate encapsulated liposomes (CEL) abrogate the anti-tumor and anti-fibrotic activity of a CD40 agonist in the KPC model (11, 31). However, it remained possible that resident monocytes/macrophages targeted by liposomes may regulate the activity of inflammatory monocytes in vivo. Therefore, we next examined the impact of depleting each of these myeloid subsets on the capacity of a CD40 agonist to facilitate degradation of extracellular matrix in PDAC tumors. To do this, we used CEL and anti-Ly6C depleting antibodies to selectively deplete Ly6Clo resident monocytes/macrophages and Ly6Chi inflammatory monocytes/macrophages, respectively (Supplementary Figures S4A-F, S5A-C and S6A-B). We found that depletion of either myeloid subset effectively eliminated the anti-fibrotic activity of anti-CD40 treatment (Figure 2, A and B). As CEL does not deplete tumor-associated macrophages (11, 31), these findings suggested a cross-talk between resident monocytes/macrophages residing outside of the tumor microenvironment and tumor-infiltrating Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes/macrophages. Consistent with this possibility, we found that resident monocytes/macrophages targeted by liposomes (CEL) were necessary for a CD40 agonist to induce the infiltration of Ly6C+ macrophages into PDAC tumors in KPC mice (Figure 2C, Supplementary Figure S7A). Thus, our findings show a role for both resident monocytes/macrophages and Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes/macrophages in mediating anti-fibrotic activity induced with a CD40 agonist.

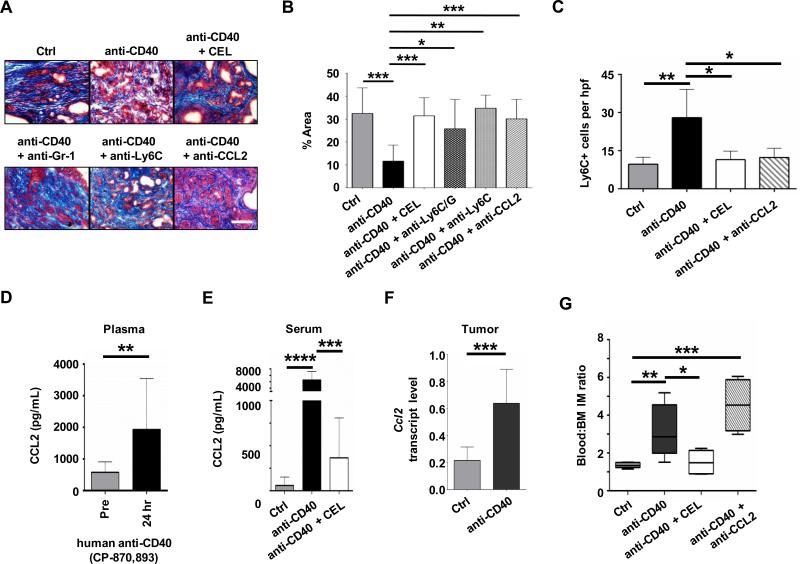

Figure 2. Anti-fibrotic activity of a CD40 agonist requires CCL2-dependent inflammatory monocyte recruitment to tumor tissue.

KPC mice were treated with isotype control antibody, anti-CD40, or anti-CD40 in combination with clodronate encapsulated liposomes (CEL), anti-Gr-1, anti-Ly6C or anti-CCL2. Shown are (A) representative images of PDAC sections stained with Masson's trichrome to detect extracellular matrix deposition (blue) one day after treatment and (B) quantification of extracellular matrix. n = 3-9 mice per group. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) Quantification of Ly6C+ myeloid cells in PDAC tumors of KPC mice one day after treatment. n=3-4 mice per group. (D) Plasma CCL2 levels in PDAC patients at baseline (Pre) and 24 hours post treatment with the fully human CD40 agonist CP-870,893 n=5-13 subjects per group. Significance determined using Mann-Whitney test. (E) Serum CCL2 levels in KPC mice one day after treatment with isotype control (Ctrl) or anti-CD40 antibodies administered with or without CEL. n=7-14 mice per group. (F) Relative Ccl2 mRNA levels in PDAC implanted tumors from mice at one day after treatment. n=9-10 mice per group. (G) Ratio of peripheral blood:bone marrow F4/80+ Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes (IM) one day after treatment. n = 4-6 mice per group. Significance testing was performed using unpaired 2-tailed Student's t test, unless otherwise specified. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001.

The recruitment of monocyte subsets to tissues is dependent on distinct chemokine signals with inflammatory monocytes responding to CCL2, a ligand of CCR2 (32). In patients treated with a fully human CD40 agonist, we detected increased levels of CCL2 within the peripheral blood one day after treatment (Figure 2D). Similar findings were observed in mice treated with a CD40 agonist where CCL2 levels were found to increase in the serum (Figure 2E) as well as tumor tissue (Figure 2F) one day after treatment. Consistent with previous reports (33, 34), we found that tumor cells were a rich source of CCL2 (Supplementary Figure S7B). In the peripheral blood, though, the increase in CCL2 levels was inhibited by depletion of resident monocytes/macrophages using CEL (Figure 2E). Based on this finding, we hypothesized that resident monocytes/macrophages may regulate mobilization of inflammatory monocytes into the peripheral blood with subsequent infiltration into tumor tissue that is dependent on CCL2. Consistent with this hypothesis, we detected an increase in the ratio of inflammatory monocytes within the peripheral blood to bone marrow in response to anti-CD40 treatment that was dependent on resident monocytes/macrophages (Figure 2G). While bone marrow mobilization of inflammatory monocytes did not require CCL2 (Figure 2G), antibody neutralization of CCL2 inhibited the infiltration of Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes/macrophages into tumor tissue (Figure 2C, Supplementary Figure S7A) and subsequent degradation of the extracellular matrix (Figure 2, A and B). Together, these findings demonstrate that CD40-induced degradation of the extracellular matrix that surrounds PDAC requires CCL2-dependent recruitment of Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes/macrophages, a process that is regulated by resident monocytes/macrophages which are present outside of the tumor microenvironment and act to promote inflammatory monocyte mobilization into the peripheral blood.

IFN-γ redirects inflammatory monocytes to degrade fibrosis in PDAC

Inflammatory monocytes are well-described proponents of cancer (17, 34). However, their activity is inherently pliable allowing for adaptation to distinct microenvironments (14). Our findings show that CD40 agonists can redirect inflammatory monocytes in PDAC with anti-fibrotic activity. However, the signals that regulate this biology are unknown. We hypothesized that CD40 agonists may induce the release of soluble factors that shift the polarity of inflammatory monocytes in vivo. Therefore, we first investigated the cytokine response induced by anti-CD40 treatment. In mice, we found that anti-CD40 antibodies stimulated the systemic release of cytokines, including IFN-γ and IL-12, regardless of the presence of a tumor, illustrating that CD40 agonists induce a non-tumor specific immune activation (Figure 3A and Supplementary Figure S8A). Further, this systemic immune activation produced by anti-CD40 treatment was dependent on IFN-γ (Supplementary Figure S8B).

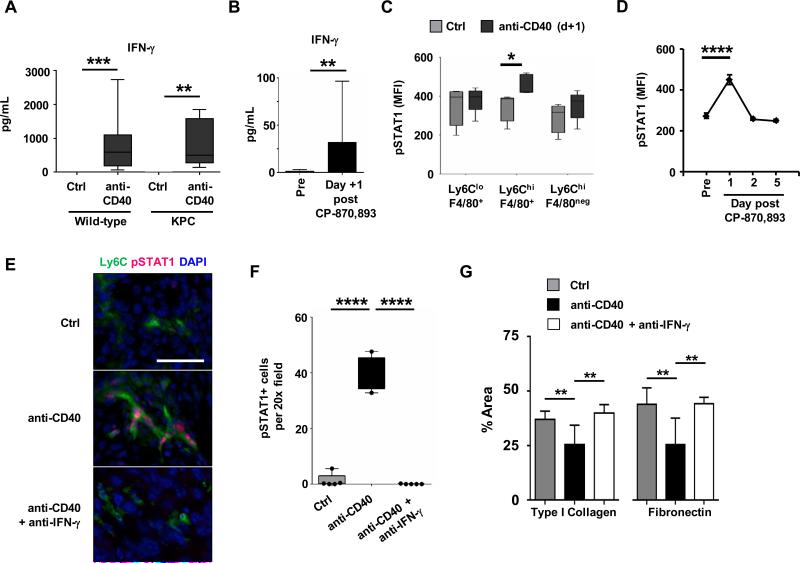

Figure 3. IFN-γ/STAT-1 signaling is necessary to redirect inflammatory monocytes with anti-fibrotic activity.

(A) Wild-type non-tumor bearing mice and KPC tumor-bearing mice were treated with isotype control (Ctrl) or anti-CD40 antibody. Serum was collected 24 hours after treatment for analysis. Shown are serum levels (pg/mL) of IFN-γ. n=17-20 mice per group for wild-type and n=10 mice per group for KPC. **, P<0.01; ***, P< 0.001. (B) Plasma cytokine levels were determined in PDAC patients at baseline (Pre) and 24 hours (Day +1) post treatment with the fully human CD40 agonist CP-870,893. Shown are levels (pg/mL) for IFN-γ. n=13 patients at baseline; n=5 patients after CP-870,893; **, P < 0.01; Mann-Whitney test. (C) Intracellular flow cytometry detection of pSTAT1 in murine peripheral blood leukocyte subsets one day after treatment. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. n=5 per group, from two independent experiments; *, P<0.05, unpaired t-test. (D) Shown is pSTAT1 expression in human monocytes treated with plasma collected from PDAC patients at baseline (Pre) and multiple time points after CP-870,893 treatment. n=3; ****, P<0.0001, one-way Anova with Bonferroni correction for multiple pairwise comparison testing. (E) Representative immunofluorescence images showing co-localization of pSTAT1 in Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes in PDAC tumors of KPC mice one day after treatment. Scale bar, 50 μm. (F) Quantification of pSTAT1 expression detected one day after treatment by immunofluorescence staining of tumor sections. n=4-5 mice per group; ****, P < 0.0001; unpaired 2-tailed t-test. (G) Quantification of extracellular matrix protein within tumors. Tumor sections were analyzed one day after treatment with control (Ctrl) or anti-CD40 antibodies with or without anti-IFN-γ antibody neutralization. n=5-9 mice per group; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; unpaired 2-tailed t-test determined from 4-6 images per mouse.

To understand whether a similar response is observed in PDAC patients treated with a fully human CD40 agonist, we examined plasma samples obtained at baseline and one day after treatment. In patients, we also found an increase in both IFN-γ and IL-12 (Figure 3B and Supplementary Figure S8C). Additionally, we observed increases in chemokines regulated by IFN-γ including IP-10 and MIG, further supporting the activation of this pathway in vivo (Supplementary Figure S8C).

Based on the importance of IFN-γ for driving the systemic cytokine release seen with a CD40 agonist, we next investigated a role for IFN-γ in stimulating tumor-infiltrating monocytes with anti-fibrotic activity. To do this, we examined for the expression of phosphorylated STAT1 (pSTAT1), which is induced by IFN-γ signaling. In mice, we found elevated pSTAT1 levels in Ly6Chi inflammatory monocytes within the peripheral blood at one day after anti-CD40 treatment indicating that monocytes become systemically activated prior to their infiltration into tumor tissue (Figure 3C). Similarly, we found that patient-derived plasma obtained at one day after anti-CD40 treatment, compared to baseline and multiple other time points, induced pSTAT1 expression in human monocytes (Figure 3D, Supplementary Figure S9A-C). We also found a striking increase in pSTAT1 expression by Ly6C+ macrophages in tumors of KPC mice one day after anti-CD40 treatment with pSTAT1 expression blocked by IFN-γ neutralization in vivo (Figure 3, E and F).

We next determined the significance of IFN-γ for Ly6C+ monocytes/macrophages to facilitate extracellular matrix degradation in PDAC. We found that neutralization of IFN-γ in vivo blocked extracellular matrix loss induced with anti-CD40 treatment (Supplementary Figure S10). Further, IFN-γ was necessary for Ly6C+ monocytes/macrophages to facilitate depletion of dominant components of the extracellular matrix including type I collagen and fibronectin (Figure 3G). Together these findings identify the IFN-γ/pSTAT1 signaling axis as a critical pathway for stimulating tumor-infiltrating monocytes/macrophages with anti-fibrotic properties.

Inflammatory monocytes regulate the MMP expression profile in PDAC tumors

Macrophages can support cancer fibrosis by interacting with fibroblasts and producing soluble factors that promote their differentiation and subsequent deposition of extracellular matrix proteins (35). We first considered the possibility that CD40 agonists might decrease fibrosis in PDAC by inducing the loss of matrix-producing fibroblasts within the tumor microenvironment. However, we previously reported no impact of anti-CD40 treatment on the frequency of FAP+ fibroblasts within PDAC tumors (31). We also observed no changes in transcript levels of matrix proteins including type I collagen and fibronectin (Supplementary Figure S11A-B, Supplementary Table S1). In addition, FAP+ fibroblast proliferation was not altered with anti-CD40 treatment (Supplementary Figure S11C). Based on this data, we next considered whether CD40 agonists might induce active degradation of extracellular matrix proteins in PDAC. Consistent with this, we found that anti-CD40 treatment selectively depleted type I collagen (TIC) and fibronectin (FN) without altering hyaluronan (HA) content within tumors (Supplementary Figure S12A-B). Because TIC and FN are long-lived resilient fibrillar proteins, this finding suggested a role for matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which are specific enzymes capable of mediating degradation of TIC and FN. In non-malignant disorders, inflammatory monocytes have been found to regulate fibrosis resolution through the production of MMPs (20). Thus, we hypothesized that inflammatory monocytes responding to anti-CD40 treatment may acquire expression of distinct MMPs which selectively degrade components of the extracellular matrix that surrounds PDAC.

To investigate the role of MMPs in PDAC, we established a transplantable tumor model that reproduced a microenvironment indistinguishable from tumors arising spontaneously in the KPC mouse model (Supplementary Figure S13A-F). This was achieved by deriving low passage (<12 passages) tumor cell lines from spontaneously arising PDAC tumors isolated from KPC mice backcrossed onto the C57BL/6 genetic background. PDAC tumors established by subcutaneous injection in C57BL/6 mice developed a microenvironment marked by extensive fibrosis and an immune infiltrate dominated by myeloid cells (Supplementary Figure S13A-F). In this model, similar to our findings in KPC mice, we observed a decrease in extracellular matrix content with anti-CD40 treatment that was dependent on a robust infiltration of Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes/macrophages (Supplementary Figure S14A-D). Gene expression analysis of whole tumor lysates revealed an increase in multiple Mmps in response to anti-CD40 treatment (Supplementary Figure S15) suggesting a shift in the MMP profile within the tumor microenvironment. In contrast, minimal effect on other extracellular matrix proteins and adhesion molecules was observed (Supplementary Figure S15). Consistent with this analysis, we also found by qRT-PCR a shift in the gene expression profile of Mmps, but not tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (Timps), within tumors treated with a CD40 agonist compared to control (Figure 4A, Supplementary Table S1).

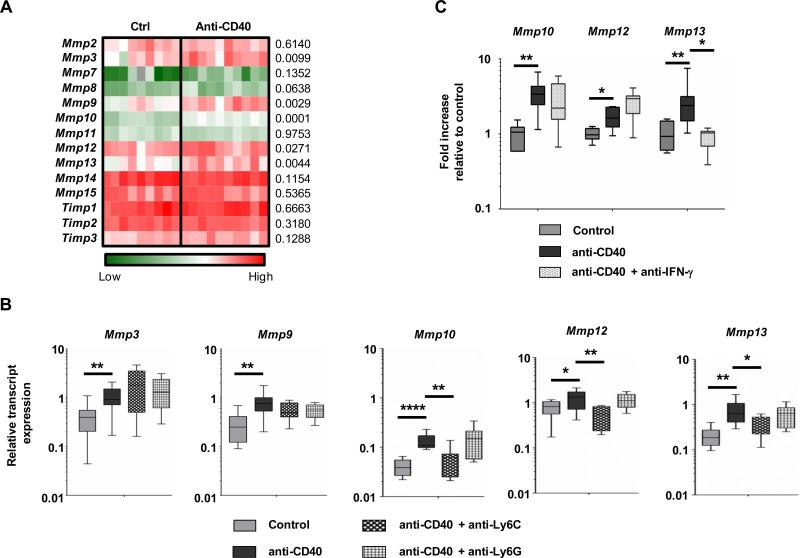

Figure 4. CD40 agonist induces a shifts in the MMP gene expression profile in tumors that is dependent on inflammatory monocytes and IFN-γ.

(A) Heat map showing global gene expression in tumor homogenates from mice with implanted PDAC tumors one day after treatment with control (n = 9) or anti-CD40 (n = 10). Statistical significance was determined using one-way Anova with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons testing. P values are shown to right of heat map. (B) Tumor-bearing mice were treated with control or anti-CD40 with or without depletion of Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes or Ly6G+ granulocytes. Shown is relative transcript expression for Mmp3, Mmp9, Mmp10, Mmp12, and Mmp13. n=5-10 mice per group. (C) qRT-pCR analysis from tumor homogenate cDNA isolated one day after treatment. Displayed are fold changes in Mmp genes relative to control treatment. For panels B-C, significance testing was performed using unpaired 2-tailed Student's t test. *, P < 0.05; **, P<0.01; ****, P<0.0001.

Because Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes/macrophages were necessary for anti-fibrotic activity induced with a CD40 agonist, we next examined their requirement for shifting the MMP profile within tumors. We found that anti-CD40 treatment enhanced expression of Mmp 3, 9, 10, 12 and 13 but only changes in Mmp 10, 12, and 13 were dependent on Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes/macrophages (Figure 4B). Further, these changes in Mmp expression were still observed when Ly6G+ granulocytes were depleted (Figure 4B). Thus, these data indicate a role for Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes/macrophages in altering the Mmp profile within the tumor microenvironment of PDAC.

MMP production is necessary for anti-CD40 agonists to degrade fibrosis in PDAC

To understand the mechanism by which Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes/macrophages acquire the capacity to facilitate degradation of fibrosis in PDAC, we developed an in vitro model to simulate the tumor microenvironment in which murine-derived myeloid cells were applied to a collagen-based matrix containing human PDAC tumor cells. With this in vitro system, changes in Mmp expression unique to myeloid cells compared to tumor cells could be detected based on Mmp gene sequence variations seen between species. We found that myeloid cells applied to this system expressed low levels of Mmp10 and Mmp13 and high levels of Mmp12 (Supplementary Figure S16A-C). In response to stimulation with IFN-γ, myeloid cells exhibited a significant increase in only Mmp13 expression when applied to this in vitro model (Supplementary Figure S16C) consistent with our in vivo findings after anti-CD40 treatment (Figure 4C). Here, we found that CD40-dependent changes in Mmp13 expression seen in tumors in vivo were abrogated with IFN-γ neutralization, which demonstrates the importance of IFN-γ for shifting the Mmp profile in tumors (Figure 4C). Consistent with this premise, we also detected increased Mmp13 transcripts by RNA in situ hybridization in PDAC tumors from KPC mice one day after anti-CD40 treatment (Supplementary Figure S17).

We next examined for MMP protein expression within PDAC tumors after anti-CD40 treatment compared to control. To do this, we first administered a pan-MMP substrate (MMPsense), which becomes fluorescent in vivo when cleaved by a broad spectrum of active MMPs. While we found evidence of enzymatically active MMPs primarily within F4/80+ macrophages and Ly6Chi macrophages within the tumor microenvironment, we detected no change in the total presence of active MMPs among these cells with anti-CD40 treatment (Supplementary Figure S18A-B). This finding is again consistent with a shift in the MMP expression profile within tumors that is induced by a CD40 agonist rather than induction of global MMP activity. In further support of this notion, we observed an increase in MMP13 expressing cells within tumors one day after anti-CD40 treatment that was abrogated by anti-Ly6C antibody treatment as well as IFN-γ neutralization (Figure 5A). Interestingly, MMP13 expression was detected not only in F4/80+ myeloid cells but also FAP+ fibroblasts (Figure 5B, Supplementary Figure S19A-C).

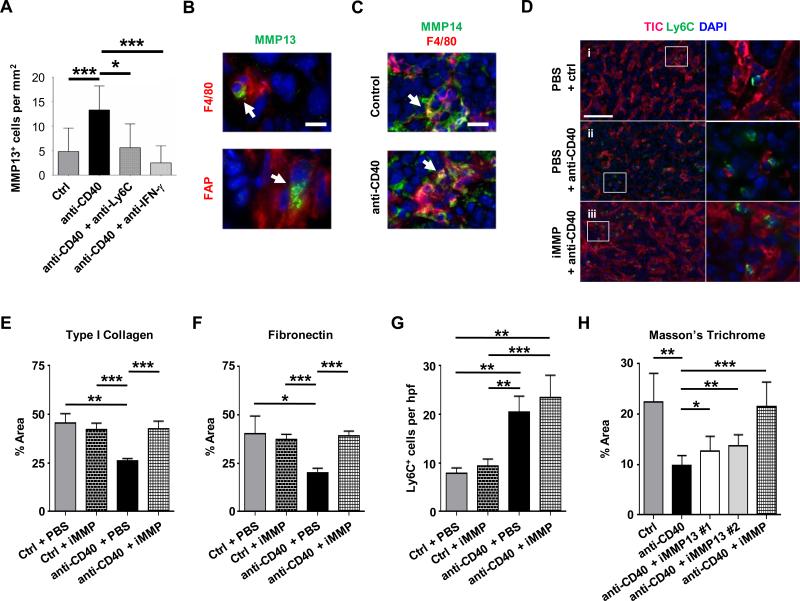

Figure 5. Anti-fibrotic activity of a CD40 agonist is dependent on MMPs.

Mice with implanted PDAC tumors were analyzed one day after treatment with isotype control or anti-CD40 antibody with or without anti-Ly6C or anti-IFN-γ antibodies. (A) Shown is quantification by immunofluorescence staining of MMP13 expressing cells in tumors. n=5-12 mice per group. (B) Representative immunofluorescence images showing MMP13 (green) expression by F4/80+ (red, top panel) and FAP+ (red, bottom panel) cells in tumors one day after treatment with anti-CD40. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Representative immunofluorescence images showing MMP14 (green) expression by F4/80+ (red) cells in tumors after treatment with control (top panel) and anti-CD40 (bottom panel). Scale bar, 20 μm. (D) Mice with implanted tumors were analyzed one day after treatment with isotype control or anti-CD40 with or without a broad spectrum MMP inhibitor (iMMP; Actinonin). Representative immunofluorescence images show type I collagen (TIC, red) among Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes (green) one day after treatment. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). One representative image is shown out of five images per tumor section per group. Scale bar, 100 μm. (E) Quantification of type I collagen and (F) fibronectin within tumors after isotype control (Ctrl) or anti-CD40 treatment with or without MMP inhibitor (iMMP; Actinonin). n=3-4 mice per group. (G) Quantification of Ly6C+ cells in tumor tissue after treatment. n=3-4 mice per group. (H) Quantification of extracellular matrix detected in tumors by Masson's Trichrome one day after treatment with isotype control or anti-CD40 antibodies with or without selective inhibitors of MMP13 (iMMP13 #1, WAY-170523; iMMP13 #2, 544678-85-5) or a broad spectrum MMP inhibitor (iMMP, Actinonin). n=4-8 per group. For panels A and E-H, significance testing was performed using unpaired 2-tailed Student's t-test. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

Like most MMPs, MMP13 is secreted as an inactive pro-form that must be cleaved for it to actively degrade collagen. Therefore, we examined for the presence of enzymes which have known capacity to activate MMP13. These enzymes include MMP2 and MMP14 (36, 37). By gene expression analysis, Mmp14 was expressed at five-fold higher levels than Mmp2 although neither was altered by treatment with a CD40 agonist (Supplementary Figure S20). Analysis of MMP14 protein expression within tumors by immunofluorescence imaging also revealed robust staining of MMP14 which was primarily seen within F4/80+ macrophages of control and anti-CD40 treated tumors in both the implantable (Figure 5C) and KPC PDAC models (Supplementary Figure S19C). Thus, tumors may be primed and ready to activate MMP13, which when expressed can then degrade the collagen-dense matrix that surrounds tumors.

We next examined the effect of MMP inhibition on the capacity of monocytes/macrophages responding to anti-CD40 treatment to mediate depletion of fibrosis in PDAC. Within 18 hours of anti-CD40 therapy, Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes/macrophages were found dispersed within tumor tissue and importantly, were located within areas displaying a loss of extracellular matrix (Figure 5D). In contrast, MMP inhibition was found to block TIC and FN degradation (Figure 5D-F, Supplementary Figure S21A-B) without impairing Ly6C+ inflammatory monocyte/macrophage recruitment to the tumor microenvironment (Figure 5G). Finally. consistent with a role for MMP13 in fibrosis degradation induced by tumor-infiltrating inflammatory monocytes/macrophages, we found that collagen degradation detected by Masson's trichrome was blocked, at least in part, by two selective inhibitors of MMP13 (Figure 5H, Supplementary Figure S22).

CD40 agonists enhance chemotherapy efficacy in an IFN-γ, MMP and Ly6C-dependent manner

Dense fibrosis that surrounds PDAC is a significant barrier to chemotherapeutic efficacy (6, 7, 38). Based on our findings that CD40 agonists alter extracellular matrix components in PDAC, we hypothesized that they may also be used to improve the efficacy of chemotherapy. To investigate this possibility, we first examined the kinetics of fibrosis depletion within PDAC tumors after anti-CD40 treatment. We found that the anti-fibrotic effect induced by a CD40 agonist was maintained for approximately one week with the onset of new matrix deposition first seen at approximately 4 days after treatment (Figure 6, A and B). Anti-CD40 therapy was also found to induce a hemorrhagic necrosis within tumors that was most pronounced on day 2 after therapy and could be seen on gross imaging of bisected tumors (Figure 6, A and C, Supplementary Figure S23A-C). However, in contrast to data reported with targeting hyaluronan (6, 7), we found that CD31+ blood vessels remained collapsed (Supplementary Figure S24A-B) despite fibrosis degradation and enhanced vascular leakage detected using Evans Blue dye (Supplementary Figure S23B).

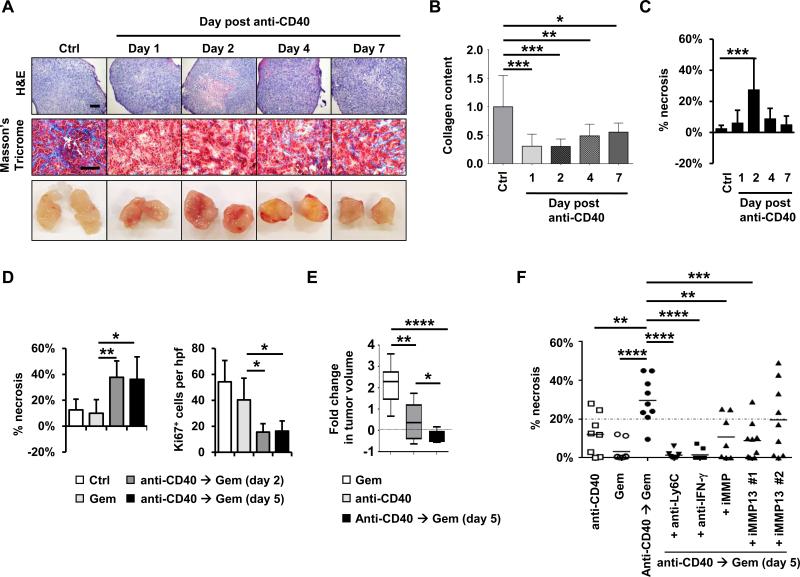

Figure 6. CD40 agonist improves gemcitabine efficacy in PDAC.

(A) Representative H&E, Masson's Trichrome, and gross images of implanted PDAC tumors obtained from mice at defined time points after treatment with anti-CD40 antibodies with comparison to isotype control (Ctrl). Scale bars, 500 μm (H&E) and 100 μm (Masson's Trichrome). (B) Quantification of collagen content in PDAC tumors detected by Masson's trichrome relative to control treatment. n=7-8 tumors per group. (C) Quantification of tumor necrosis seen on H&E imaging. n=7-8 tumors per group. (D) Mice with implanted PDAC tumors were treated with anti-CD40 on day 0 followed by gemcitabine on day 2 or 5 as indicated with comparison to gemcitabine alone. Shown is quantification of tumor necrosis and cellular proliferation (Ki67) detected by H&E and immunohistochemical staining, respectively, at one day after gemcitabine treatment. n=5 mice per group. (E) Mice with implanted PDAC tumors were treated with or without anti-CD40 antibody on day 0 followed by gemcitabine on day 5. Shown is fold change in tumor volume from time of gemcitabine treatment to 6 days later. n = 8-9 mice per group. (F) Effect of anti-Ly6C, anti-IFN-γ, broad spectrum MMP inhibitor (iMMP, Actinonin) and MMP13 specific inhibitors (iMMP13 #1, WAY-170523; iMMP13 #2, 544678-85-5) on tumor necrosis induced with gemcitabine administered 5 days after anti-CD40 therapy with comparison to anti-CD40 and gemcitabine alone. Tumor necrosis is quantified one day after treatment with gemcitabine. For panels B-F, significance testing was performed using one-way Anova with Bonferroni correction for multiple pairwise comparisons or unpaired 2-tailed Student's t test. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001.

We next examined the capacity of a CD40 agonist to “condition” the tumor microenvironment for enhanced chemotherapeutic efficacy. We found that gemcitabine administered two days after treatment with a CD40 agonist produced extensive tumor necrosis and significantly inhibited tumor proliferation, as determined by decreased Ki67 expression within tumor cells (Figure 6D, Supplementary Figures S25A-B and S26A-B). In contrast, no significant impact on tumor cell death or proliferation was observed with gemcitabine alone which is consistent with its minimal clinical activity (39).

We then tested the impact on tumor growth of administering gemcitabine after a CD40 agonist. We found that gemcitabine treatment at two days after anti-CD40 therapy induced tumor stasis/regression that was superior to gemcitabine alone and was dependent on both Ly6C+ cells and MMPs (Supplementary Figure S27). However, administering gemcitabine treatment at this time after a CD40 agonist was poorly tolerated and mice showed significant weight loss (Supplementary Figure S28), with a 30% mortality and a requirement for supportive care with fluid therapy. This poor tolerability to gemcitabine treatment when administered after a CD40 agonist has been reported previously (40). However, our observation that the anti-fibrotic effect of a CD40 agonist is maintained for at least one week (Figure 6A and C) suggested the possibility that delaying gemcitabine treatment to a later time may also be efficacious.

We next examined the anti-tumor effect and tolerability of gemcitabine administered five days after a CD40 agonist as this timing of treatment was previously found to be well-tolerated in patients and to produce promising clinical activity (10, 11). With this treatment timing, we found that a CD40 agonist significantly enhanced the anti-tumor activity of gemcitabine with marked necrosis and inhibition of tumor proliferation seen one day after gemcitabine treatment that was comparable to administering gemcitabine two days after anti-CD40 therapy (Figure 6D, Supplementary Figure S25). In addition, combination treatment with a CD40 agonist followed by gemcitabine five days later was well-tolerated (Supplementary Figure S28) and induced tumor regression/stasis that was superior to either treatment alone (Figure 6E). Moreover, the capacity of a CD40 agonist to enhance the efficacy of gemcitabine chemotherapy was dependent on Ly6C+ cells, IFN-γ, and MMPs including MMP13 (Figure 6F). Together, our findings reveal a novel mechanism by which tumor-infiltrating Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes/macrophages responding to IFN-γ and CCL2 can be induced to shift the MMP profile within tumors for rapid degradation of fibrosis in PDAC leading to enhanced tumor sensitivity to gemcitabine chemotherapy.

Discussion

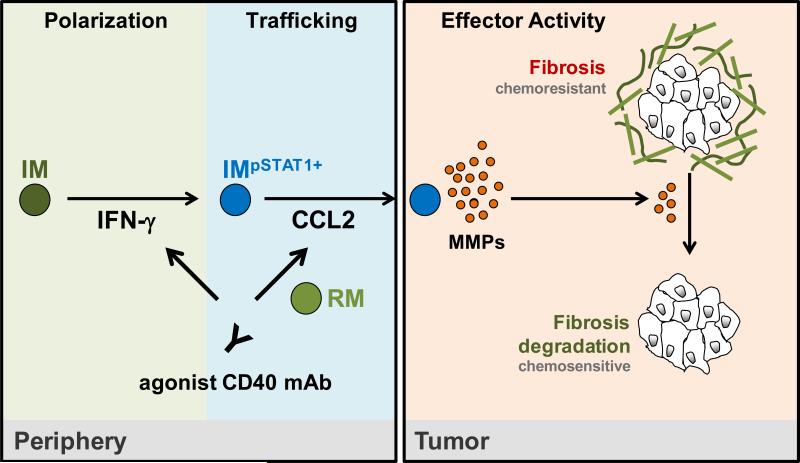

Inflammatory monocytes/macrophages are continually recruited to the tumor microenvironment where they most commonly support tumor development, growth, and metastasis (17, 34). For this reason, strategies are underway in the clinic to evaluate the therapeutic benefit achieved with inhibiting monocyte recruitment to tumor tissue, depleting monocytes in vivo, and blocking pro-tumor activities of monocytes (16, 30, 34, 41-44). However, these approaches which seek to sequester or inhibit monocytes may be at risk for a rapid rebound in tumor growth when therapy is interrupted (41). An alternative approach is to harness the myeloid response to cancer for its potential to be anti-fibrotic and to produce anti-tumor activity. We previously demonstrated that macrophages originating from peripheral blood monocytes were necessary for the efficacy of a CD40 agonist in PDAC (11). Anti-CD40 treatment was found to deplete the stroma that surrounds PDAC and to induce major tumor regressions in both mice and humans. This result implied that fibrosis in PDAC, often considered to be a rigid and irreversible phenomenon, is rather a dynamic and bidirectional process with the capacity to undergo resolution in the proper setting. Our data now show the importance of IFN-γ and CCL2 for a CD40 agonist to redirect inflammatory monocytes/macrophages to facilitate depletion of cancer fibrosis. This process was dependent on resident monocytes/macrophages which directed the mobilization of inflammatory monocytes into the peripheral blood from the bone marrow with subsequent CCL2-dependent infiltration into the tumor microenvironment. Tumor-infiltrating inflammatory monocytes/macrophages were then necessary to induce a shift in the MMP profile within tumor tissue leading to degradation of dominant extracellular matrix proteins, including type I collagen and fibronectin. These findings demonstrate the plasticity of both the myeloid response in PDAC as well as the fibrotic reaction that is a hallmark of this disease. In addition, our results reveal the key mechanistic steps (i.e monocyte polarization, trafficking, and effector activity) that are required for modulating this microenvironment through re-education of tumor-infiltrating monocytes/macrophages (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Proposed step-wise model for anti-fibrotic activity induced with a CD40 agonist in PDAC.

Treatment with a CD40 agonist induces the systemic release of IFN-γ which activates CCR2+ inflammatory monocytes (IM) and polarizes their phenotype toward anti-fibrotic (Step 1: Polarization). Inflammatory monocytes are then recruited to the tumor microenvironment in a CCL2-dependent manner that is regulated by resident monocytes/macrophages (RM) residing outside of the tumor microenvironment (Step 2: Trafficking). Within the tumor microenvironment, tumor infiltrating inflammatory monocytes alter the MMP profile leading to rapid degradation of extracellular matrix proteins including type I collagen and fibronectin (Step 3: Effector Activity). Together, depletion of extracellular matrix components induced by inflammatory monocytes enhances the sensitivity of tumors to gemcitabine chemotherapy.

In our study, IFN-γ was necessary for a CD40 agonist to redirect tumor-infiltrating monocytes/macrophages with anti-fibrotic properties. This finding suggests that alternative immunomodulatory approaches such as toll-like receptor agonists or activators of anti-tumor T cell immunity, which can induce the systemic release of IFN-γ, may also be capable of stimulating monocytes/macrophages in vivo to degrade cancer fibrosis. We also found selective activation of the IFN-γ/pSTAT1 pathway in tumor-infiltrating Ly6C+ macrophages and in Ly6Chi inflammatory monocytes within the peripheral blood suggesting a role for IFN-γ produced outside of the tumor microenvironment in modulating the polarity of monocytes/macrophages prior to their infiltration into tumor tissue. The source of IFN-γ that directs this biology in vivo in response to anti-CD40 treatment is unknown but is unlikely to be T cells as they were dispensable for treatment efficacy (11). We have also found that depletion of NK cells in vivo does not alter the serum levels of IFN-γ induced with a CD40 agonist (data not shown) consistent with previously published work (45). While macrophages have also been suggested to be a source of IFN-γ induced by CD40 ligation in vivo (45), we did not observe any impact of depleting macrophages in vivo using clodronate encapsulated liposomes on the capacity of a CD40 agonist to induce the systemic release of IFN-γ (data not shown).

Chemokines direct the infiltration of monocytes into tumor tissue (46, 47). Within PDAC tumors, both malignant and non-malignant cells may produce CCL2 (34). We have found CCL2 to be necessary for anti-CD40 treatment to recruit anti-fibrotic monocytes to PDAC tumors. The importance of CCL2 for anti-CD40 efficacy suggests that tumors which lack or lose the capacity to produce CCL2 may be unresponsive to anti-CD40 therapy. Previous work in a breast cancer model has highlighted the importance of CCL2 produced by both malignant and non-malignant cells for recruiting monocytes to metastatic lesions (34). At present, the precise role of CCL2 production by malignant and non-malignant cells in PDAC for anti-CD40 efficacy remains unknown. However, variability in CCL2 expression by tumor cells may explain the treatment response heterogeneity that was seen in patients with PDAC treated with a CD40 agonist in combination with gemcitabine chemotherapy (10).

The anti-fibrotic mechanism mediated by inflammatory monocytes was dependent on MMPs in which MMP13 was found to be the only up-regulated MMP capable of degrading both collagen and fibronectin. However, additional MMPs, including MMP10 and MMP12, were also increased by anti-CD40 treatment in an inflammatory monocyte-dependent manner. These MMPs may be important for degrading fibronectin and other extracellular matrix proteins that comprise the dense fibrotic matrix that surrounds PDAC. MMP13 is a member of the family of zinc-dependent endopeptidases and is secreted in an inactive pro-form that is then cleaved to the active enzyme by extracellular proteinases, including MMP2 and MMP14 (36, 48). We observed expression of both MMP2 and MMP14 which may be required for activating collagenase activity by MMP13. Recently, MMP13 has been suggested to be a key enzyme produced by monocytes during the resolution phase of liver fibrosis induced with carbon tetrachloride (21). We propose that the balance of MMPs, rather than a single MMP, present within the tumor microenvironment is regulated by monocytes and can be shifted from pro- to anti-fibrotic. As monocytes have been found to be critical regulators of the resolution phase of fibrosis in several non-malignant disorders including lung and liver fibrosis (20, 49, 50), our data suggest the importance of tumor-infiltrating inflammatory monocytes as therapeutic targets to manipulate fibrosis in cancer. Moreover, our findings provide new insights into the importance of MMPs in tumors for regulating chemotherapeutic efficacy. In particular, we have identified a novel role for MMP13 for enhancing the anti-tumor activity of gemcitabine chemotherapy in PDAC.

Communication between a tumor and its surrounding microenvironment is a complex process. Whereas some elements of fibrosis (e.g myofibroblasts) have been found to suppress tumor aggressiveness (8, 9), these same components which establish a dense extracellular matrix can protect malignant cells from cytotoxic therapies by impeding the penetration of small molecules delivered to the tumor bed (6, 7, 38). Elimination of this fibrotic barrier can improve the delivery of chemotherapy to tumor tissue resulting in enhanced survival in mouse models of PDAC. In our studies, we have found that monocyte-dependent resolution of fibrosis in PDAC induced with a CD40 agonist also improves the efficacy of gemcitabine chemotherapy. This enhancement in chemotherapy efficacy was dependent on IFN-γ, Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes/macrophages, and MMPs, in particular MMP13. This finding demonstrates the potential of the immune response to cancer to be harnessed for improving standard cytotoxic therapies. The timing of chemotherapy administration after a CD40 agonist, though, is critical. Whereas gemcitabine administered at 2 days post a CD40 agonist was poorly tolerated, delaying gemcitabine to 5 days post anti-CD40 treatment was both well-tolerated and efficacious. This is the same timing of treatment that was previously investigated in PDAC patients and found to be safe with evidence of therapeutic activity.

Immune based strategies (e.g. CD40 agonists) also offer the additional therapeutic possibility of direct anti-tumor activity. To this end, we observed significant tumor necrosis within 48 hours after anti-CD40 treatment. Tumor-associated macrophages from PDAC tumors treated with a CD40 agonist were previously shown to acquire direct anti-tumor activity which may be critical for controlling tumor outgrowth after modulating the stroma (11). This finding may explain why immunotherapies capable of depleting stromal elements (10-12) can suppress tumor outgrowth whereas strategies that merely eliminate stromal elements may accelerate tumor progression (8, 9).

In summary, the immune reaction to PDAC is emerging as a key target for cancer therapy. Within the tumor microenvironment, myeloid cells dominate and support a microenvironment that is immunosuppressive, resistant to standard therapies and conducive to tumor outgrowth (15, 18, 31, 33, 51). While the use of CD40 agonists has previously suggested the ability to shift the polarity of this microenvironment in vivo (11), the mechanistic basis of this biology and therapeutic implications have remained unknown. Our data now define the key steps in this process and show that the myeloid infiltrate recruited to PDAC can be re-educated (Figure 7). In addition, our findings identify a novel role for a CD40 agonist as a “lead-in” therapy to enhance the efficacy of chemotherapeutic and possibly biologic treatments for PDAC. Given the strong tropism of inflammatory monocytes for human cancers, these data support the investigation of therapeutic approaches that redirect inflammatory monocytes, rather than deplete them, in order to harness their recruitment to tumors and unleash their anti-fibrotic and anti-tumor potential.

Methods

Animals

KrasLSL-G12D/+, Trp53LSL-R172H/+, Pdx1-Cre (KPC) mice have been previously described (29). These mice were backcrossed to the C57BL/6 genetic background. Details are described in supplementary methods. Animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institute of Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Pennsylvania.

Clinical samples

Plasma was collected by centrifugation of peripheral blood from patients treated on a previously described study (10, 11) that evaluated CP-870,893, a fully human agonist CD40 monoclonal antibody, in combination with gemcitabine for the treatment of patients with chemotherapy naive advanced PDAC. Samples were stored at −80C. Quantification of soluble cytokine and chemokines was determined using Luminex bead array technology (Life Technologies) as previously described (52). Written informed consent was required. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by local institutional review boards.

Animal experiments

For KPC mice, tumors were detected by palpation and confirmed by ultrasonography as previously described (11). In some experiments, low-passage PDAC cell lines derived from backcrossed KPC mice were implanted subcutaneously into syngeneic C57BL/6 mice and allowed to develop over 14-17 days to approximately 5 mm in diameter before mice were enrolled into treatment studies. Treatment studies are described in more detail in supplementary methods.

Histology, immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence analysis

Immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence and histopathology were performed on frozen tissue sections. RNA in situ hybridization was performed on paraffin embedded tissue sections. Frozen sections were air dried and fixed with 3% formaldehyde. Primary antibodies against mouse antigens and detailed methods are described in supplementary methods. Fluorescence and brightfield images were acquired on IX83 inverted (Olympus) and BX43 upright (Olympus) microscopes, respectively.

Immune analysis of mouse samples

Peripheral blood samples were obtained from the tail vein of mice as previously described (11). Flow cytometry analysis of peripheral blood cell subsets and cytokines is described in detail in the supplementary methods.

Cell lines

7940B was derived from a primary spontaneous PDAC tumor arising in the body of the pancreas (C57BL/6) of a male transgenic Pdx-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D; LSL-Trp53R172H (KPC) mouse. Passage 5 of the cell line was established and cryopreserved. Cell lines between passage 6-12 were used in experiments. Cell line authentication was based on histological analysis of the implanted cell line with comparison to the primary tumor from which the cell line was derived (Supplementary Figure S13A-F). Cell lines were tested for mycoplasma contamination and grown in DMEM with 10% FBS supplemented with 83 μg/mL gentamicin.

RNA and gene expression array

Tumor tissue was processed and stored in TRIzol at −80C. Tumor lysates were thawed on ice and allowed to equilibrate to room temperature before RNA was isolated using a Qiagen RNeasy Mini kit according to manufacturer protocol. RNA was collected in RNase-free water and quantified using a NanoDrop Spectrophotometer. Gene expression array analyses and qRT-PCR used are described in detail in supplementary methods.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism software. Box plots represent the first to third quartile of data with the median shown. Whiskers in the box plot represent the minimum and maximum values. Multiple comparisons testing was performed using one-way Anova with Bonferroni correction. All other comparisons were determined by Student's t or Mann-Whitney tests where indicated.

Supplementary Material

Statement of significance.

We report that CD40 agonists improve chemotherapy efficacy in pancreatic carcinoma by redirecting tumor-infiltrating monocytes/macrophages to induce fibrosis degradation that is dependent on matrix metalloproteinases. These findings provide novel insight into the plasticity of monocytes/macrophages in cancer and their capacity to regulate fibrosis and modulate chemotherapy efficacy in pancreatic carcinoma.

Acknowledgements

We thank Michael Kalos and Erica Suppa for human cytokine analyses and Qian-Chun Yu, Hongwei Yu, Daniel Martinez, Jonathan P. Katz, Adam Bedenbaugh and Santiago Lombo Luque for advice and technical assistance. We also thank Cynthia Clendenin for technical assistance and provision of KPC mice used in some experiments.

Financial support: This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant K08 CA138907 (G.L.B.), NCI T32 CA009140 (JAF), a Molecular Biology and Molecular Pathology and Imaging Cores of the Penn Center for the Molecular Studies in Digestive and Liver Diseases grant (P30 DK050306), W.W. Smith Charitable Trust grant #C1204 (G.L.B.), Department of Defense W81XWH-12-0411 (G.L.B.), the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation grant DRR-15-12 for which G.L.B. is the Nadia's Gift Foundation Innovator of the Damon Runyon-Rachleff Innovation Award and by Grant 2013107 from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (G.L.B.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryan DP, Hong TS, Bardeesy N. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;371:1039–49. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1404198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark CE, Beatty GL, Vonderheide RH. Immunosurveillance of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: insights from genetically engineered mouse models of cancer. Cancer Lett. 2009;279:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feig C, Gopinathan A, Neesse A, Chan DS, Cook N, Tuveson DA. The pancreas cancer microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4266–76. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feig C, Jones JO, Kraman M, Wells RJ, Deonarine A, Chan DS, et al. Targeting CXCL12 from FAP-expressing carcinoma-associated fibroblasts synergizes with anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:20212–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320318110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Provenzano PP, Cuevas C, Chang AE, Goel VK, Von Hoff DD, Hingorani SR. Enzymatic targeting of the stroma ablates physical barriers to treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:418–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobetz MA, Chan DS, Neesse A, Bapiro TE, Cook N, Frese KK, et al. Hyaluronan impairs vascular function and drug delivery in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2013;62:112–20. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhim AD, Oberstein PE, Thomas DH, Mirek ET, Palermo CF, Sastra SA, et al. Stromal elements act to restrain, rather than support, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:735–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozdemir BC, Pentcheva-Hoang T, Carstens JL, Zheng X, Wu CC, Simpson TR, et al. Depletion of carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and fibrosis induces immunosuppression and accelerates pancreas cancer with reduced survival. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:719–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beatty GL, Torigian DA, Chiorean EG, Saboury B, Brothers A, Alavi A, et al. A phase I study of an agonist CD40 monoclonal antibody (CP-870,893) in combination with gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:6286–95. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beatty GL, Chiorean EG, Fishman MP, Saboury B, Teitelbaum UR, Sun W, et al. CD40 agonists alter tumor stroma and show efficacy against pancreatic carcinoma in mice and humans. Science. 2011;331:1612–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1198443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lo A, Wang LC, Scholler J, Monslow J, Avery D, Newick K, et al. Tumor-Promoting Desmoplasia Is Disrupted by Depleting FAP-Expressing Stromal Cells. Cancer research. 2015;75:2800–10. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanahan D, Coussens LM. Accessories to the crime: functions of cells recruited to the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:309–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:889–96. doi: 10.1038/ni.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qian BZ, Pollard JW. Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell. 2010;141:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Palma M, Lewis CE. Macrophage regulation of tumor responses to anticancer therapies. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:277–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franklin RA, Liao W, Sarkar A, Kim MV, Bivona MR, Liu K, et al. The cellular and molecular origin of tumor-associated macrophages. Science. 2014;344:921–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1252510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Long KB, Beatty GL. Harnessing the antitumor potential of macrophages for cancer immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2:e26860. doi: 10.4161/onci.26860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noy R, Pollard JW. Tumor-associated macrophages: from mechanisms to therapy. Immunity. 2014;41:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duffield JS, Forbes SJ, Constandinou CM, Clay S, Partolina M, Vuthoori S, et al. Selective depletion of macrophages reveals distinct, opposing roles during liver injury and repair. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:56–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI22675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramachandran P, Pellicoro A, Vernon MA, Boulter L, Aucott RL, Ali A, et al. Differential Ly-6C expression identifies the recruited macrophage phenotype, which orchestrates the regression of murine liver fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E3186–95. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119964109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pellicoro A, Ramachandran P, Iredale JP, Fallowfield JA. Liver fibrosis and repair: immune regulation of wound healing in a solid organ. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:181–94. doi: 10.1038/nri3623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murray PJ, Wynn TA. Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:723–37. doi: 10.1038/nri3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xue J, Sharma V, Hsieh MH, Chawla A, Murali R, Pandol SJ, et al. Alternatively activated macrophages promote pancreatic fibrosis in chronic pancreatitis. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7158. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Condeelis J, Pollard JW. Macrophages: obligate partners for tumor cell migration, invasion, and metastasis. Cell. 2006;124:263–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.French RR, Chan HT, Tutt AL, Glennie MJ. CD40 antibody evokes a cytotoxic T-cell response that eradicates lymphoma and bypasses T-cell help. Nat Med. 1999;5:548–53. doi: 10.1038/8426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diehl L, den Boer AT, Schoenberger SP, van der Voort EI, Schumacher TN, Melief CJ, et al. CD40 activation in vivo overcomes peptide-induced peripheral cytotoxic T-lymphocyte tolerance and augments anti-tumor vaccine efficacy. Nat Med. 1999;5:774–9. doi: 10.1038/10495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sotomayor EM, Borrello I, Tubb E, Rattis FM, Bien H, Lu Z, et al. Conversion of tumor-specific CD4+ T-cell tolerance to T-cell priming through in vivo ligation of CD40. Nat Med. 1999;5:780–7. doi: 10.1038/10503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hingorani SR, Wang L, Multani AS, Combs C, Deramaudt TB, Hruban RH, et al. Trp53R172H and KrasG12D cooperate to promote chromosomal instability and widely metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:469–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanford DE, Belt BA, Panni RZ, Mayer A, Deshpande AD, Carpenter D, et al. Inflammatory Monocyte Mobilization Decreases Patient Survival in Pancreatic Cancer: A Role for Targeting the CCL2/CCR2 Axis. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:3404–15. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beatty GL, Winograd R, Evans RA, Long KB, Luque SL, Lee JW, et al. Exclusion of T Cells From Pancreatic Carcinomas in Mice Is Regulated by Ly6C(low) F4/80(+) Extratumoral Macrophages. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:201–10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:953–64. doi: 10.1038/nri1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bayne LJ, Beatty GL, Jhala N, Clark CE, Rhim AD, Stanger BZ, et al. Tumor-derived granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor regulates myeloid inflammation and T cell immunity in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:822–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qian BZ, Li J, Zhang H, Kitamura T, Zhang J, Campion LR, et al. CCL2 recruits inflammatory monocytes to facilitate breast-tumour metastasis. Nature. 2011;475:222–5. doi: 10.1038/nature10138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Comito G, Giannoni E, Segura CP, Barcellos-de-Souza P, Raspollini MR, Baroni G, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts and M2-polarized macrophages synergize during prostate carcinoma progression. Oncogene. 2013;33:2423–31. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knauper V, Will H, Lopez-Otin C, Smith B, Atkinson SJ, Stanton H, et al. Cellular mechanisms for human procollagenase-3 (MMP-13) activation. Evidence that MT1-MMP (MMP-14) and gelatinase a (MMP-2) are able to generate active enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17124–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knauper V, Bailey L, Worley JR, Soloway P, Patterson ML, Murphy G. Cellular activation of proMMP-13 by MT1-MMP depends on the C-terminal domain of MMP-13. FEBS Lett. 2002;532:127–30. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03654-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olive KP, Jacobetz MA, Davidson CJ, Gopinathan A, McIntyre D, Honess D, et al. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling enhances delivery of chemotherapy in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Science. 2009;324:1457–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1171362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burris HA, 3rd, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML, Modiano MR, et al. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2403–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nowak AK, Robinson BW, Lake RA. Synergy between chemotherapy and immunotherapy in the treatment of established murine solid tumors. Cancer research. 2003;63:4490–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bonapace L, Coissieux MM, Wyckoff J, Mertz KD, Varga Z, Junt T, et al. Cessation of CCL2 inhibition accelerates breast cancer metastasis by promoting angiogenesis. Nature. 2014;515:130–3. doi: 10.1038/nature13862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mitchem JB, Brennan DJ, Knolhoff BL, Belt BA, Zhu Y, Sanford DE, et al. Targeting tumor-infiltrating macrophages decreases tumor-initiating cells, relieves immunosuppression, and improves chemotherapeutic responses. Cancer research. 2013;73:1128–41. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Germano G, Frapolli R, Belgiovine C, Anselmo A, Pesce S, Liguori M, et al. Role of macrophage targeting in the antitumor activity of trabectedin. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:249–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Priceman SJ, Sung JL, Shaposhnik Z, Burton JB, Torres-Collado AX, Moughon DL, et al. Targeting distinct tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells by inhibiting CSF-1 receptor: combating tumor evasion of antiangiogenic therapy. Blood. 2010;115:1461–71. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-237412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buhtoiarov IN, Lum H, Berke G, Paulnock DM, Sondel PM, Rakhmilevich AL. CD40 ligation activates murine macrophages via an IFN-gamma-dependent mechanism resulting in tumor cell destruction in vitro. J Immunol. 2005;174:6013–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murdoch C, Giannoudis A, Lewis CE. Mechanisms regulating the recruitment of macrophages into hypoxic areas of tumors and other ischemic tissues. Blood. 2004;104:2224–34. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bonecchi R, Locati M, Mantovani A. Chemokines and cancer: a fatal attraction. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:434–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mitchell PG, Magna HA, Reeves LM, Lopresti-Morrow LL, Yocum SA, Rosner PJ, et al. Cloning, expression, and type II collagenolytic activity of matrix metalloproteinase-13 from human osteoarthritic cartilage. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:761–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI118475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fallowfield JA, Mizuno M, Kendall TJ, Constandinou CM, Benyon RC, Duffield JS, et al. Scar-associated macrophages are a major source of hepatic matrix metalloproteinase-13 and facilitate the resolution of murine hepatic fibrosis. J Immunol. 2007;178:5288–95. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gibbons MA, MacKinnon AC, Ramachandran P, Dhaliwal K, Duffin R, Phythian-Adams AT, et al. Ly6Chi monocytes direct alternatively activated profibrotic macrophage regulation of lung fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:569–81. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1719OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weizman N, Krelin Y, Shabtay-Orbach A, Amit M, Binenbaum Y, Wong RJ, et al. Macrophages mediate gemcitabine resistance of pancreatic adenocarcinoma by upregulating cytidine deaminase. Oncogene. 2013;33:3812. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beatty GL, Haas AR, Maus MV, Torigian DA, Soulen MC, Plesa G, et al. Mesothelin-specific chimeric antigen receptor mRNA-engineered T cells induce antitumor activity in solid malignancies. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2:112–20. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.