Abstract

Context:

Abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) is associated with high morbidity and mortality among trauma patients. Several clinical and laboratory findings have been suggested as markers for ACS, and these may point to different types of ACS and complications.

Aims:

This study aims to identify the strength of association of clinical and laboratory variables with specific adverse outcomes in trauma patients with ACS.

Settings and Design:

A 5-year retrospective chart review was conducted at three Level I Trauma Centers in the City of Chicago, IL, USA.

Subjects and Methods:

A complete set of demographic, pre-, intra- and post-operative variables were collected from 28 patient charts.

Statistical Analysis:

Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to determine the strength of association between 29 studied variables and eight end outcomes.

Results:

Thirty-day mortality was associated strongly with the finding of an initial intra-abdominal pressure >20 mmHg and moderately with blunt injury mechanism. A lactic acid >5 mmol/L on admission was moderately associated with increased blood transfusion requirements and with acute renal failure during the hospitalization. Developing ACS within 48 h of admission was moderately associated with increased length of stay in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), more ventilator days, and longer hospital stay. Initial operative intervention lasting more than 2 h was moderately associated with risk of developing multi-organ failure. Hemoglobin level <10 g/dL on admission, ongoing mechanical ventilation, and ICU stay >7 days were moderately associated with a disposition to long-term support facility.

Conclusions:

Clinical and lab variables can predict specific adverse outcomes in trauma patients with ACS. These findings may be used to guide patient management, improve resource utilization, and build capacity within trauma centers.

Keywords: Abdominal compartment syndrome, acute renal failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, complications, intra-abdominal hypertension, length of stay, markers, multi-organ failure, patient outcomes, risk factors, trauma

INTRODUCTION

Abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) is a rare clinical entity that has been described in critically ill patients including medical, surgical, and trauma populations with high morbidity and mortality rates reported among those patients affected by it.[1,2,3] ACS is defined as “sustained intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) exceeding 20 mmHg associated with new organ dysfunction or failure.”[4] The incidence of ACS is estimated to be anywhere from 0.5% to 36% depending on the patient population studied and the definition used to describe the condition.[1,5,6] The pathophysiology of ACS is directly related to the increased IAP of the disease process and the consequent effects of this increased pressure on various organ systems. Distension of the abdomen from the increased IAP pushes up the diaphragm and compresses the thoracic cavity leading to impairment of respiration and ventilation. The increased IAP compresses the vena cava which causes a decrease in venous return (preload) and, therefore, results in a decreased cardiac output. This decreased cardiac output also results in decreased perfusion to the kidneys resulting in impairment of renal function. Adverse effects of ACS can also include ischemia within the splanchnic circulation resulting in a systemic inflammatory response leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), acute renal failure (ARF) (abrupt decline of kidney function over a period of <7 days and manifested by a rise in creatinine of 1.5 times the baseline), increased intracranial pressure, and multi-organ failure (MOF) (dysfunction of two or more organ systems requiring intervention to maintain homeostasis).[5,6,7] Treatment for ACS consists of relieving the increased IAP by means of a decompressive laparotomy. Patients surviving ACS may suffer long-term adverse sequelae including depression, chronic organ failure, the need for ventral hernia repair, and prolonged need for rehabilitation, in addition to expensive costs of hospital care.[8,9]

ACS has three main types: Primary ACS, which occurs due to an abdominopelvic pathology (e.g., penetrating trauma, intraperitoneal hemorrhage, pancreatitis); secondary ACS, which occurs due to conditions not originating from the abdominopelvic region (e.g., large-volume resuscitation, burn injuries); and recurrent ACS, which describes recurrence of ACS after a successful treatment of a previous episode.[4] Several different sets of clinical and laboratory markers of ACS have been proposed, including net fluid balance, urine output, base deficit on Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission, peak airway pressure measurement, and ratio of gastric mucosal to arterial CO2 (GAPCO2), among others.[10,11] Each ACS sub-type likely has its own unique pathophysiology and set of markers, necessitating a different diagnostic and therapeutic approach in each type.[12,13,14] In addition, some markers may be associated with the development of particular ACS complications, but these relationships have not been well-established. The purpose of this study is to identify the strength of association between different clinical and laboratory variables and the occurrence of specific adverse outcomes in trauma patients diagnosed with ACS.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study design

A 5-year retrospective chart review was conducted at three Level I Trauma Centers in the Chicago metropolitan area in Illinois, USA. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from each site included in this study. All three trauma centers serve a large, urban population and combined, they admit approximately 7000 patients annually, with approximately 25–30% of the admissions attributable to penetrating mechanisms of injury.

Patient selection and data collection

All patients with the diagnosis of ACS from August 1, 2006 to July 31, 2011, were identified using each institution's Trauma Registry of the American College of Surgeons database. The database search was performed using the following ICD-9 Codes: 958.93 traumatic compartment syndrome abdomen and ICD-729.73 nontraumatic compartment syndrome abdomen. The inclusion criteria were age >18 years, admission due to traumatic injury and survival past first 24 h of admission.

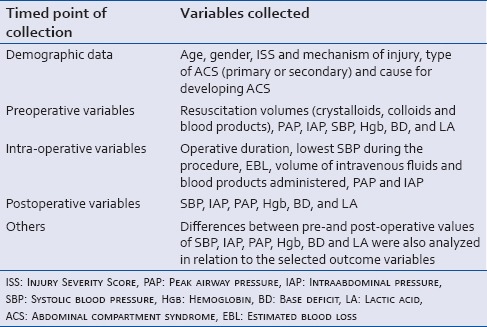

Once all eligible patients were identified, a complete set of demographic, preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative data was collected for all patients included in the study. A total of 29 variables were collected for each patient. A complete listing of the variables examined in this study can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

The complete set of collected clinical and laboratory markers

The defined operation being measured was an exploratory laparotomy for any penetrating or blunt abdominal trauma. All patients who underwent this primary operation and then were suspected to have developed ACS based on a combination of clinical exam and elevated bladder pressures (>20 mmHg) were then taken back to the operating room. Return to the operating room consisted of a decompressive laparotomy and based on the surgeon's judgment and additional operative factors including the patient's hemodynamic status and bowel edema. Fascial closure occurred at the time of the decompressive laparotomy or at a subsequent return to the operating room based on surgical findings.

Primary outcomes for the study were death and the development of major complications within 30 days after the operation. The following events were defined as major complications: ARF, ARDS, and MOF. Secondary outcomes examined in the study included hospital and ICU length of stays (LOSs), ventilator days, and final disposition of surviving patients on discharge from the hospital (i.e., home or step-down facility).

Statistical analysis

Demographic data were summarized as a percentage of totals. The complete set of collected preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative data was summarized by means with standard deviations. Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to determine the strength of association between each of the 29 studied variables and the eight end outcomes: 30 days mortality, ventilator days, hospital and ICU LOSs, development of ARF, ARDS, or MOF and final disposition from the hospital. Correlation coefficient scores between 0.4 and 0.5 were considered to show a moderate association between a variable and an outcome whereas scores higher than 0.5 were considered to show a strong association.

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA® 11 (STATA Corp, College Station, TX, USA). A significance threshold of P < 0.05 was designated for statistical significance.

RESULTS

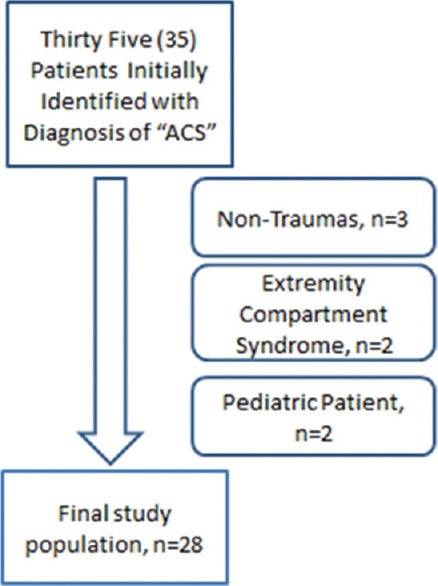

Thirty-five patients with the diagnosis of ACS were identified; seven patients were excluded; three nontrauma, two misdiagnoses for extremity compartment syndrome and two patients for being under 18 years of age. Ultimately, 28 patients were included in this study. Figure 1 provides a diagrammatic representation of the patient selection process.

Figure 1.

Patient selection

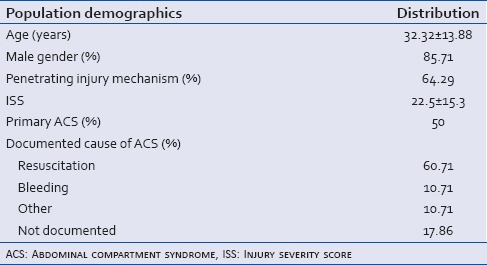

Patients diagnosed with ACS were overwhelmingly male (85.7%) and primarily victims of blunt injuries (64.3%). Massive resuscitation (>10 units of blood or blood products in a 24 h time period) was the most commonly documented cause for ACS development (60.7%), followed by bleeding and other causes (10.7% each). Primary and secondary ACS were evenly represented in the study population (50% each). The demographic data for all patients included in the study are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of demographic data for trauma patients with abdominal compartment syndrome

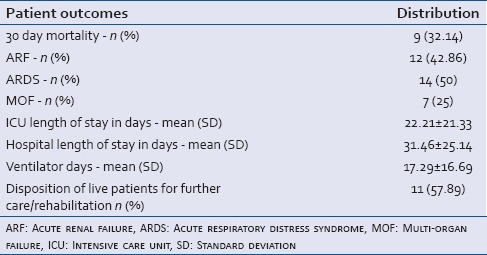

Regarding primary outcomes, the analysis showed that the overall 30-day mortality among this patient population was 32.14%. The incidence of ARF, ARDS, and MOF was 42.86%, 42.86%, 25% respectively. For secondary outcomes; the average ICU LOS was 22.21 ± 21.33 days, the average hospital LOS was 31.46 ± 25.1 days, and the average LOS on a ventilator was 17.3 ± 16.7. Regarding the disposition of surviving patients (n = 19); 42.11% were discharged home whereas 57.89% were discharged to a rehabilitation center or a nursing facility for long-term care. Table 3 summarizes the patient outcomes for this study.

Table 3.

Outcomes of trauma patients with abdominal compartment syndrome

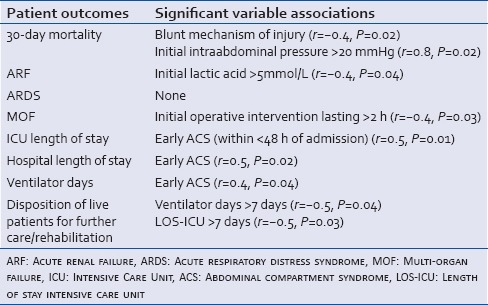

Pearson's correlation coefficient showed the following associations: Developing ACS within <48 h of admission was strongly associated with increased 30-day mortality rate (r = 0.8, P = 0.02); and strongly associated with increased LOS in the ICU (r = 0.5, P = 0.01) and longer stay in the hospital (r = 0.5, P = 0.02). It was moderately associated with longer stay on the ventilator (r = 0.4, P = 0.04) and moderately associated with a blunt mechanism of injury (r = −0.4, P = 0.02). A lactic acid level >5 mmol/L on admission was strongly associated with transfusion requirements of >10 units of blood within the first 24 h of admission (r = 0.5, P = 0.04), and was moderately associated with the development of ARF (r = 0.4, P = 0.04) during hospital stay. Initial operative intervention lasting more than 2 h was moderately associated with increased risk to develop MOF (r = −0.4, P = 0.03). Finally, a disposition to long-term support facility instead of being discharged home was moderately associated with requiring mechanical ventilation or staying in the ICU for >7 days (r = −0.5, P = 0.04) and (r = −0.5, P = 0.03) respectively. This study did not identify risk factors for developing ARDS. The correlation of pertinent clinical and laboratory markers with the eight end outcomes are outlined in Table 4.

Table 4.

Pearson's correlation coefficient showing the effects of significant clinical and laboratory markers on patient outcomes

DISCUSSION

ACS is a rare condition among trauma patients admitted to Level 1 urban trauma centers. Patients sustaining ACS in these settings were found to have a high mortality rate, and significant morbidities including ARF, ARDS, and MOF. ACS was associated with increased resource utilization, including longer ventilator days and longer stay in the ICU and in the hospital, with a high percentage of patients discharged to long-term care facilities for continued care. In addition, this study identified several clinical and laboratory variables that had strong or moderate associations with specific adverse outcomes in trauma patients diagnosed with ACS.

It is important to note that this study does not suggest a cause-effect relationship between clinical and laboratory variables with the specific patient outcomes studied. Instead, findings from this study can provide clinicians with an enhanced awareness when monitoring clinical progress and interpreting laboratory data for trauma patients who develop ACS. The findings from this study can also provide the basis for risk stratification studies that may help physicians and trauma centers to anticipate and plan for future needs for this patient population. This study was not designed to explore mechanisms by which certain variables may correlate with specific outcomes among ACS patients; rather, it invites further research to delineate these processes and offer a better understanding of the complex pathophysiological pathways by which ACS may trigger such cascades during its clinical course. Delineating the strength of association between clinical and laboratory findings to specifically observed complications may help explain pathophysiological pathway by which these complications develop.

The findings of this study are significant for several reasons; this study adds to the limited number of studies that have examined how certain clinical and laboratory markers correlate with specific outcomes observed in trauma patients diagnosed with ACS.[10,11,12] In addition, previous research on ACS consisted largely of single-institutional reviews, which may restrict the general applicability of their findings. This study drew data from three urban Level I Trauma centers, which may provide for findings that are more generalizable. In addition, applying Pearson's correlation coefficient provided tangible conclusions for the findings.

Despite its strengths, this study has several limitations, most notably the small number of patients recruited. While we do acknowledge that we were initially surprised by this finding, we have not found any epidemiological studies reporting the crude incidence of ACS among all trauma patients admitted to trauma centers; available studies have looked at subgroups of trauma patients including those admitted to the ICU, with an incidence estimated to be 1% and those undergoing damage control surgery, with an incidence of 14%; both those findings may add legitimacy to the low incidence in this study.[1,6] Other factors may have also contributed to this low number of ACS in this study, including the use of retrospective administrative data with the potential for miscoding and inaccurate or incomplete medical records. It is also possible that Chicago trauma centers were “early adopters” of the principles of damage control laparotomies and local surgeons were more likely to leave the fascia open after the index case if there was large-volume resuscitation or extensive blood loss.[15,16]

Similarly, another possible limitation is that we did not have a comparison group for our study. We considered a matched analysis, but ultimately decided against it for three main reasons. First, the matching would have been challenging; for example, patients with multiple long bone fractures and a head injury may have the same ISS as someone with a gunshot wound to the abdomen, but would clearly have different risks of ACS. Second, we acknowledge our imperfect understanding of the pathophysiology of ACS. Many patients who suffer large volume blood loss or undergo massive resuscitation do not develop ACS; in a comparison study, we may simply be identifying differences in the host response to injury, not the effects of ACS itself.[17,18] Third, if, as noted above, Chicago surgeons have been early adopters of damage control principles with temporary abdominal closures, finding a true comparison group would be unlikely.

Finally, there may be additional confounding factors that were not examined in this study, which may have skewed the findings.

Future areas of research include expanding the number of variables studied to identify the strength of association of additional markers to specific outcomes in trauma patients with intraabdominal hypertension in addition to those diagnosed with ACS. Increasing the power of the study by including patients from suburban and rural trauma centers may provide additional insights into other associations not appreciated in the current study. Due to the rarity of the condition, it is important to encourage trauma teams to continue publishing their experiences and observations among patients diagnosed with ACS, so we can improve outcomes associated with this morbid syndrome.

Financial support and sponsorship

Northwestern University.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Malbrain ML, Chiumello D, Pelosi P, Wilmer A, Brienza N, Malcangi V, et al. Prevalence of intra-abdominal hypertension in critically ill patients: A multicentre epidemiological study. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:822–9. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2169-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ivatury RR, Porter JM, Simon RJ, Islam S, John R, Stahl WM. Intra-abdominal hypertension after life-threatening penetrating abdominal trauma: Prophylaxis, incidence, and clinical relevance to gastric mucosal pH and abdominal compartment syndrome. J Trauma. 1998;44:1016–21. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199806000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daugherty EL, Hongyan Liang, Taichman D, Hansen-Flaschen J, Fuchs BD. Abdominal compartment syndrome is common in medical intensive care unit patients receiving large-volume resuscitation. J Intensive Care Med. 2007;22:294–9. doi: 10.1177/0885066607305247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malbrain ML, Cheatham ML, Kirkpatrick A, Sugrue M, Parr M, De Waele J, et al. Results from the international conference of experts on intra-abdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome. I Definitions. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:1722–32. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0349-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hong JJ, Cohn SM, Perez JM, Dolich MO, Brown M, McKenney MG. Prospective study of the incidence and outcome of intra-abdominal hypertension and the abdominal compartment syndrome. Br J Surg. 2002;89:591–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raeburn CD, Moore EE, Biffl WL, Johnson JL, Meldrum DR, Offner PJ, et al. The abdominal compartment syndrome is a morbid complication of postinjury damage control surgery. Am J Surg. 2001;182:542–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00821-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schein M, Wittmann DH, Aprahamian CC, Condon RE. The abdominal compartment syndrome: The physiological and clinical consequences of elevated intra-abdominal pressure. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:745–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugrue M. Abdominal compartment syndrome. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2005;11:333–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ccx.0000170505.53657.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheatham ML, Safcsak K, Sugrue M. Long-term implications of intra-abdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome: Physical, mental, and financial. Am Surg. 2011;77(Suppl 1):S78–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNelis J, Marini CP, Jurkiewicz A, Fields S, Caplin D, Stein D, et al. Predictive factors associated with the development of abdominal compartment syndrome in the surgical intensive care unit. Arch Surg. 2002;137:133–6. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balogh Z, McKinley BA, Holcomb JB, Miller CC, Cocanour CS, Kozar RA, et al. Both primary and secondary abdominal compartment syndrome can be predicted early and are harbingers of multiple organ failure. J Trauma. 2003;54:848–59. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000070166.29649.F3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrell BR, Melander S. Identifying the association among risk factors and mortality in trauma patients with intra-abdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome. J Trauma Nurs. 2012;19:182–9. doi: 10.1097/JTN.0b013e318261d2f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dutton RP, Mackenzie CF, Scalea TM. Hypotensive resuscitation during active hemorrhage: Impact on in-hospital mortality. J Trauma. 2002;52:1141–6. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200206000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrison CA, Carrick MM, Norman MA, Scott BG, Welsh FJ, Tsai P, et al. Hypotensive resuscitation strategy reduces transfusion requirements and severe postoperative coagulopathy in trauma patients with hemorrhagic shock: Preliminary results of a randomized controlled trial. J Trauma. 2011;70:652–63. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31820e77ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayberry JC, Goldman RK, Mullins RJ, Brand DM, Crass RA, Trunkey DD. Surveyed opinion of American trauma surgeons on the prevention of the abdominal compartment syndrome. J Trauma. 1999;47:509–13. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199909000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatch QM, Osterhout LM, Ashraf A, Podbielski J, Kozar RA, Wade CE, et al. Current use of damage-control laparotomy, closure rates, and predictors of early fascial closure at the first take-back. J Trauma. 2011;70:1429–36. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31821b245a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ivatury RR. Update on open abdomen management: Achievements and challenges. World J Surg. 2009;33:1150–3. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balogh Z, McKinley BA, Cocanour CS, Kozar RA, Valdivia A, Sailors RM, et al. Supranormal trauma resuscitation causes more cases of abdominal compartment syndrome. Arch Surg. 2003;138:637–42. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.6.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]