Abstract

Objective:

The purpose of this study was to elicit the opinions of Emergency Department (ED) physicians, currently practicing in the United States, regarding the impact of economic and regulatory factors on their management of patients exhibiting “drug seeking” behavior.

Methods:

A descriptive, cross-sectional study, utilizing a convenience sample of ED physicians located in Florida and Georgia was conducted for a period of 2 months. The inclusion criteria specified that any ED physician, currently practicing within the United States, could participate.

Results:

Of the ED physicians surveyed (n = 141), 71% reported a perceived pressure to prescribe opioid analgesics to avoid administrative and regulatory criticism and 98% related patient satisfaction scores as being too highly emphasized by reimbursement entities as a means of evaluating their patient management. Rising patient volumes and changes in the healthcare climate were cited by ED physicians as impacting their management of patients exhibiting “drug seeking” behavior.

Conclusions:

The ED physician faces unique challenges in changing healthcare and economic climates. Requirements to address pain as the “fifth vital sign,” patient satisfaction based reimbursement metrics and an economically driven rise in ED patient volume, may have inadvertently created an environment conducive to exploitation by prescription opioid abusers. There is an identified need for the development of continuing medical education and standardized regulatory and legislative protocols to assist ED physicians in the appropriate management of patients exhibiting “drug seeking” behavior.

Keywords: Drug seeking, opioids, prescribing practices, prescription monitoring

INTRODUCTION

Background

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), between 2004 and 2008, Emergency Department (ED) visits, related to the abuse of prescribed opioids, increased by 111% with a concurrent rise in visits for benzodiazepines increasing by 89%.[1] On July 1, 2011, the Florida Surgeon General declared the state to be in a public health emergency citing an average of seven deaths occurring daily due to prescription opioids and other controlled substances.[2] In November 2011, the director of the CDC, Dr. Thomas Frieden, stated “Overdoses involving prescription painkillers are at epidemic levels and now kill more Americans than heroin and cocaine combined.”[3]

Importance

Certain regulatory and economic initiatives, designed to insure the quality of medical care, were identified anecdotally by ED physicians as key challenges in the management of patients exhibiting drug seeking behavior. Increased patient volumes and time constraints associated with the use of electronic medical records (EMRs),[4] in addition to new reimbursement strategies based upon patient satisfaction scores and reduction of door-to-discharge times, create an ethical dilemma for the ED physicians attempting to curb the prescription opioid abuse epidemic.

Goals of this investigation

This study sought to elicit the opinions of practicing ED physicians to determine if economic and regulatory factors were perceived as impacting their management of patients exhibiting drug seeking behavior. Survey results may serve to identify factors impacting the public health crisis of prescription opioid abuse. Findings could be instrumental in the development of continuing medical education (CME), curricula for medical schools and residency programs, and modification of administrative protocols and legislation instrumental to the deterrence of prescription opioid abuse.

METHODS

Study design

A descriptive, cross-sectional, epidemiological study was conducted utilizing an online survey tool to assess the current opinions of practicing ED physicians with regard to the impact of economic and regulatory factors during management of patients exhibiting “drug seeking” behavior. This study design was to identify trends and commonalities observed from participant's clinical experience and training.

Selection of participants

A convenience sample of Florida and Georgia ED physicians were invited to complete the survey instrument. The inclusion criteria specified that participants must be current practicing ED physicians within the United States. Invitations were distributed to various medical/professional organizations and individual clinicians, utilizing publicly obtained E-mail and physical addresses.

Interventions

The questions were revised and tested for content validity by a group of experts in emergency medicine and education. The current survey questions were distributed and tested for content validity. The survey includes a maximum number of 39 multiple choice questions with an optional essay question at the conclusion allowing for the physician to provide additional comments. Questions were designed using a four column Likert-type scale. Options included “always,” “frequently,” “occasionally,” and “never.” Screening questions within the survey reinforced inclusion criteria. To decrease study limitations, all applicable survey questions included a provision allowing participants to provide additional comments. The provision was also made at the conclusion of the survey to add comments not addressed by survey questions. The survey received IRB approval by the University of South Florida (IRB #9509).

Methods and measurements

A pilot of this survey was developed and tested in February 2012. The final survey was conducted during October and November 2013 utilizing an online survey instrument. Subsequent to the advertised study closure date, the data were downloaded electronically by the primary researcher from the online survey tool to an Excel Spreadsheet. The data were then analyzed using SPSS analytical software.

Outcomes

Survey results are presented graphically and elaborated upon in the results section. Results are presented in these categories: Management of patients exhibiting drug seeking behavior, regulatory factors impacting ED physician practices, and economic changes impacting ED physician practices.

Analysis

The survey was conducted during October and November 2013 utilizing on online survey instrument and subsequently analyzed utilizing SPSS software (SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0). Demographics included age, length of time practicing as an ED physician, board certification status, practice venue, and description.

To evaluate trends and overall responses, descriptive statistics (e.g., averages, standard deviations, frequencies, and confidence intervals) were applied in conjunction with all survey questions. Chi-square statistics were utilized to determine differences of participants with categorical variables. A probability of 0.05 or less was considered significant when calculating the difference between the observed and anticipated responses. For questions using a Likert-type scale, Spearmen's correlation measured associations between the ranked variables. A range of −1 to +1 was used to determine the strength of correlation, and the actual value would be subjected to significance testing to determine the probability of chance. Analysis of covariance was utilized when comparing a variable in the two sub-samples with other covariates. A calculated P < 0.05 was caused to reject the relative null hypothesis and accept the alternative hypotheses indicating there are differences among sub-samples.

RESULTS

Sample demographics

The sample for this study was comprised 141 ED physicians, between 31-70 years of age, currently practicing in the United States. Forty percentage of the participants had a minimum of 20 years in emergency medicine while 9% had <2 years of experience. The majority of the participants (88%) were boarded in emergency medicine. The participants treat adult, pediatric, or a combination of these patients. Clinical practice environment includes both for-profit and nonprofit hospitals.

Management of patients exhibiting drug seeking behavior

Training

Nearly half (47%) of the participants have received CME in the last 3 years on recognition and management of prescription opioid abuse, 22% had no training at all on this topic. A majority of respondents (84%) agreed that physicians “should receive some type of specialized CME to assist them with recognition and management of prescription opioid abuse.”

Opioid abuse identification

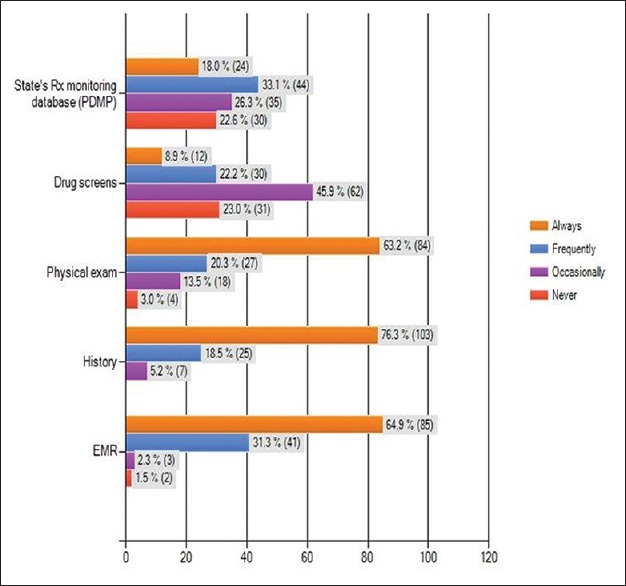

Participants were asked to comment on five methods of opioid abuse identification: Physical examination, history, use of the EMR, query of the states’ prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) database, and drug screening. Results are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Utilization of opioid abuse identification methods

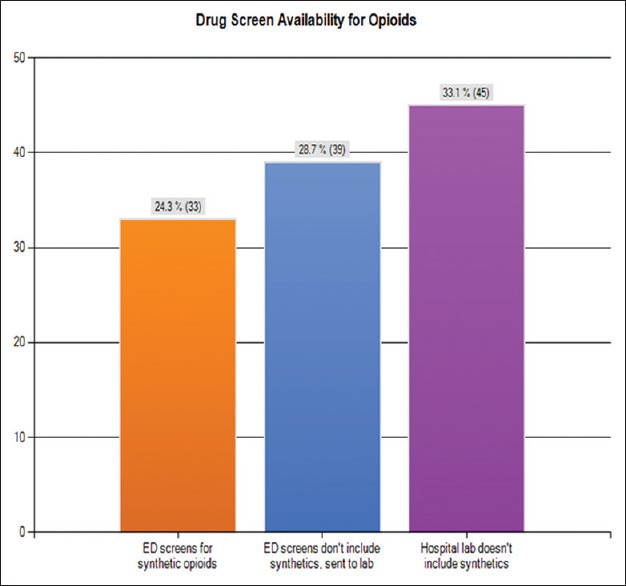

Only 25% of the respondents had the ability to screen for synthetic opioids in their respective ED's. In 29% of the respondents, testing for synthetic opioids required submission to the hospital laboratory and 33% had to send samples to an outside laboratory. Results are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Drug screen availablilty for opioids

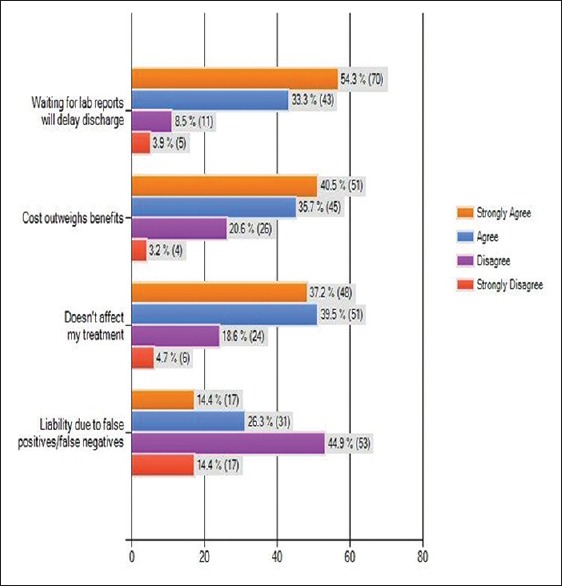

Of note, <1/5 of respondents (18%) “always” queried their state's PDMP as a means of identifying potential opioid abuse. Of those that did query the PDMP, 68% reported having received responses indicating “doctor shopping” behavior. Factors cited as discouraging use of the PDMP included being “too busy” (74%), process is too time-consuming (76%), and patient satisfaction scores could be negatively affected should opioids be refused based upon database findings (41%) and lack of awareness on how to access the PDMP (36%). Results are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Factors influencing nonutilization of drug screens prior to prescribing opioids

Factors cited as encouraging use of the PDMP included an examination indicative of drug-seeking behavior (92%), a PDMP query indicating “doctor shopping” would support their refusal to prescribe opioids (80%) and a history of past drug abuse (72%).

Opioid prescribing practices

Obtaining the patient's history, performing a physical examination and reviewing past medical records were reported as always being conducted as part of the participant's opioid prescribing practice. Twelve percentage of the respondents reported always using drug screens and the PDMP prior to prescribing opioids and while 49% “occasionally” conduct drug screens as part of their practice. The chief factor discouraging respondents from performing a drug screen prior to prescribing opioids (87%) was cited as being delayed discharge due to lab delays. Additional reasons included the perception that cost outweighs benefit (77%), and treatment is not affected by laboratory results (77%). Of those respondents utilizing drug screens, 60% reported the finding of illicit drugs and 53% found drugs not prescribed to the patient.

Regulatory and administrative factors impacting Emergency Department physician practices

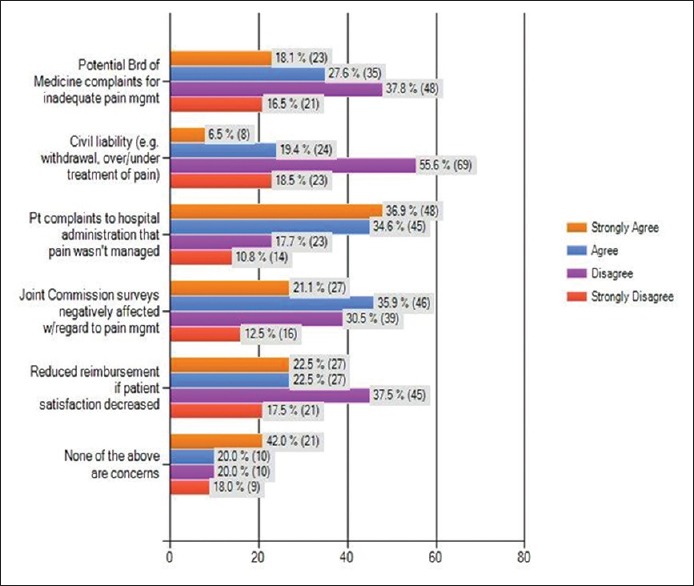

Participants were asked to provide their opinions as to how regulatory and administrative factors possibly affected their opioid prescribing practices. In 40% of the responses, either the respondent or one of their colleagues had been formally disciplined for failure to prescribe opioids. A majority of respondents (72%) felt pressured to prescribe in order to avoid administrative complaints from the patient that pain was inadequately treated. Analysis of results demonstrated several trends which are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Perceived pressures to prescribe opioids

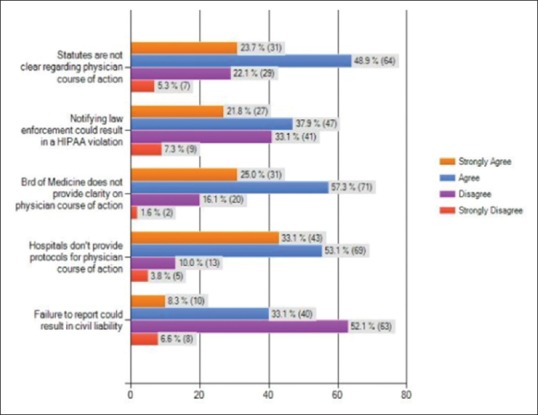

Another concern expressed that a course of action is not provided for physicians, by regulatory and administrative entities, should “doctor shopping” be suspected. A lack of clarity by hospitals (86%), by the Board of Medicine (82%) and by state statues (73%) were reported by participants. Violations of HIPAA from notifying law enforcement was cited by 60% and 41% are concerned regarding civil liability for failure to report. Analysis of results demonstrated several trends which are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Physician course of action when “doctor shopping” indicated

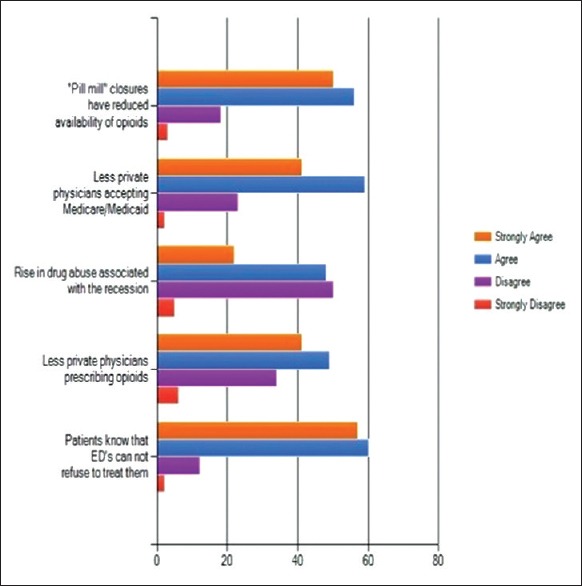

Economic changes impacting Emergency Department physician practices

A significant number of ED physicians (72%) reported an increased volume of ED patients manifesting “drug seeking” behavior within the 2 years prior to the survey. Independent t-tests revealed that respondents cited possible reasons including “less private physicians accepting Medicare/Medicaid” due to decreased reimbursement (80%) (t = −3.068, P = 0.003) and patient perception that ED's are obligated to treat them (90%) (t = −2.329, P = 0.021). Additional reasons cited were decreases in “pill mills” (83%) and less physicians being willing to prescribe opioids (70%). Analysis of results demonstrated several trends which are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Factors influencing Emergency Department patient volume

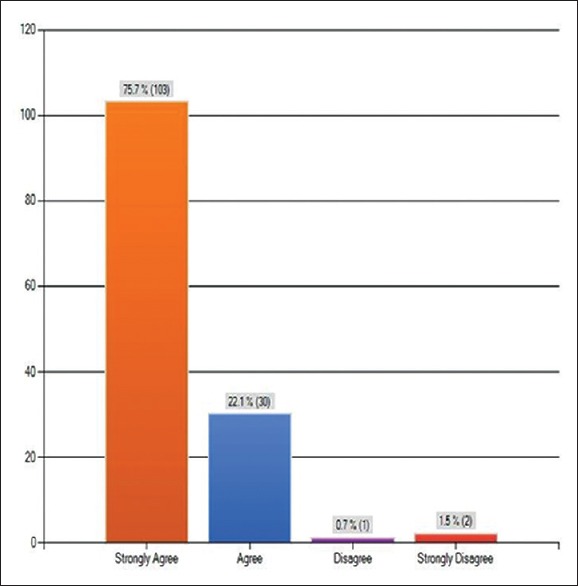

A pressure to prescribe was reported by 57% in order to avoid negative impact on Joint Commission surveys and by 46% to avoid decreased patient satisfaction scores and their direct relevance to reimbursement. A majority of respondents (98%) were of the opinion that patient satisfaction scores should not be used as a metric to assess quality patient care [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

Emphasis on patient satisfaction scores

DISCUSSION

ED physicians face a number of unique challenges in today's changing healthcare and economic climates. Ironically, a number of regulatory and economic initiatives, originally designed for the protection of patients, are now being viewed as negatively impacting ED physicians in their efforts to decrease prescription opioid abuse. Regulatory requirements to address pain as the “fifth vital sign”, healthcare entities utilizing “patient satisfaction” as a reimbursement metric and an economically driven increase in ED patient volume may have inadvertently created an environment conducive to exploitation by the prescription opioid abuser.

Management of patients exhibiting drug seeking behavior

Training

In light of the current prescription opioid epidemic, the Office of National Drug Control Policy is encouraging physician education on this topic, not only for medical schools and postgraduate programs, but also for physicians currently in practice and possessing a DEA license.

The need for some type of specialized CME in this area was supported by a large majority of survey participants. However, what is also evidenced through this study is that ED physicians would benefit most from CME-specific to emergency medicine. Unlike the private practitioner, ED physicians do not elect, which patients enter into their practice and must provide unrestricted access to all persons seeking emergency medical care as part of the EMTALA legislation. The management and care of ED patients will obviously differ from the palliative care offered by non-ED practitioners.

Opioid abuse identification

The use of a history, physical examination, and review of EMR were noted as routinely being used as means of identifying potential prescription opioid abuse. Drug screening and PDMP databases are also effective tools for identifying prescription opioid abuse yet the literature, as well as the results of our survey, suggest these entities are under-utilized. Of those respondents who did employ drug screens, greater than half of those reported finding evidence of substance abuse. This information could quite possibly impact an ED physician's prescribing practices as well as infer the need for potential dependency treatment.

When asked what discouraged participants from utilizing drug screens, only one-fourth of the respondents had the ability detect synthetic opioids (e.g., dilaudid, oxycontin, Percocet et al.) in their ED drug screens. Waiting for results from often over-burdened laboratories can result in delayed door-to-discharge times and consequently lower patient satisfaction scores– both of which are utilized by entities such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) as reimbursement metrics.

Factors discouraging PDMP utilization were observed to be both administrative and economic. Approximately, one-fourth of the sample was not registered with the PDMP, and 36% were unaware of how to gain access. This is another aspect that could be covered during training as the state departments of health can use training opportunities to share information regarding their state's PDMP. Economic concerns were again cited as the most significant factor discouraging use. The need to see increased patient volumes, the reimbursement metrics, and the time constraints necessary to query the database were all cited as concerns.

Another factor discouraging PDMP utilization is a lack of clarity as to the physician's course of action should a PDMP query indicate that the patient is “doctor shopping.” Among the specific concerns cited were decreased patient satisfaction scores should the physician refuse to prescribe an opioid and conversely, the potential civil liability for prescribing to a patient with evidence of dependency.

Ironically, what motivates some respondents to avoid using the PDMP is what motivates other to utilize the program. Many respondents view a positive PDMP query as supporting their refusal to prescribe an opioid in the event of an administrative complaint.

Opioid prescribing practices

History, physical examination, and review of EMR received the highest percentage of responses as “always” being used prior to prescribing opioids. When asked about usage of the PDMP and drug screening as prerequisites for prescribing, it was observed that fewer participants utilized the PDMP for prescribing purposes than for identification purposes. As already discussed, the vast majority of respondents are not utilizing drug screens in general and therefore are not considered part of their opioid prescribing practices.

Regulatory factors impacting Emergency Department physician practices

In 1995, the American Pain Society initiated a campaign to view pain as the “fifth vital sign” which was later adopted by The Joint Commission as is reflected in their hospital accreditation surveys.[5,6] A favorable survey and subsequent accreditation is crucial to hospitals and is also directly linked to reimbursement from agencies such as CMS.

An administrative expectation exists therefore that ED physicians will insure adequate pain management or risk decreased survey scores. Acquiescing to a patient's requests for medication, including analgesics, is not a new dilemma for ED physicians. Forty percentage of the respondents cited that either they or one of their colleagues have been formally disciplined for failure to acquiesce to a patient's request for an opioid prescription. Regulatory concerns for over- and under-prescribing opioids are well documented in the literature. A review of case law on this topic revealed no judgments found against ED physicians specifically; however, a Massachusetts physician was found to be at fault in a civil litigation where the patient lost consciousness and was involved in a fatal car accident after being prescribed an opioid analgesic.[7]

Forty-six percentage of respondents cited concerns that failure to treat pain could result in a potential Board of Medicine complaint. In a California case, Bergman versus Chin,[8] the court adjudicated on behalf of a victim's family in a case of inadequate pain management. What was significant was that the Board of Medicine had already reviewed the case and exerted no disciplinary action. Other regulatory concerns were demonstrated in that 60% of the participants were concerned that reporting “doctor shopping” patients to law enforcement could result in an HIPAA violation but conversely, failure to report “doctor shopping” could result in civil liability.

The changing economic and healthcare climates

Patient satisfaction surveys have been utilized for many years with one of the most notable surveys conducted by the Press Ganey organization. In 2002, CMS initiated their own survey which was referred to as the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS)[9] as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, HCAHPS data was implemented as a metric to calculate incentive payments as part of the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing program.[10] This represented a paradigm shift from fee-for-service reimbursement to “pay by performance” as an example, CMS can withhold 30% of the hospital's incentive monies due to unsatisfactory patient scores.

Subsequent to the Great Recession of 2008, ED patient volumes have increased significantly including a large percentage of patients financially supported by Medicaid.[11] Ninety-one percentage of the respondents confirmed the noted rise in patient volume over the last 2 years and 72% specifically noted a rise in patients exhibiting drug seeking behavior. A large majority of respondents attribute the reduced availability of opioids subsequent to “pill mill” closures. Other factors cited for the volume increase include less private physicians accepting Medicare/Medicaid (79%), a reduced number of private physicians willing to write opioid prescriptions (68%) and patient awareness that ED's are obligated to take them as patients.

A little over half of the participants cited that their hospital does support the use of the PDMP, however, three-fourths of the hospitals represented by participants do not have an active administrative protocol in place. The majority of participants expressed their preference for the initiation of a protocol with approximately 70% stating they felt this would protect them from the potential disciplinary action. However, an almost equal number felt that the protocols could potentially limit the professional judgment of the ED physician.

Limitations

To decrease study limitations, all applicable survey questions included a provision at the end of the question which provided an option for the participants to provide an opinion not included in the multiple choice options for that particular question. The provision was also made at the conclusion of the survey for participants to add comments not addressed by survey questions.

While self-reporting may represent limited accuracy, overall trends, and correlations may be helpful in future educational endeavors. Other potential limitations include:

Sampling was limited to ED physicians in Florida and Georgia potentially restricting the ability to “generalize” the population and thereby potentiating internal validity errors

The number of participants responding was voluntary therefore noncontrolled

The instrument being utilized could be completed online, therefore, the potential for errors could not be controlled by the researcher

The potential for bias could not be controlled.

As this research is nonexperimental, there is no control for extraneous variables.

CONCLUSION

In summary, the results of this study have identified several gaps in training, regulation, and administrative healthcare practices that are potentially deterring efforts of ED physicians in their management of patients with “drug-seeking” behavior. Further research is needed to identify appropriate interventions to bridge these identified gaps.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Emergency department visits involving nonmedical use of selected prescription drugs – United States, 2004–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:705–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Florida Department of Health. Declaration of Public Health Emergency. [Last accessed on 2015 Jan 10]. Available from: http://www.newsroom.doh.state.fl.us/wp-content/uploads/newsroom/2011/07/07012011-EmergencyDeclaration.pdf .

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prescription Painkiller Overdoses at Epidemic Levels. [Last accessed on 2015 Jan 10]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2011/p1101_flu_pain_killer_overdose.html .

- 4.Kunins HV, Farley TA, Dowell D. Guidelines for opioid prescription: Why emergency physicians need support. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:841–2. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-11-201306040-00631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veterans Health Administration. Pain as the 5th Vital Sign Toolkit. 2000. Oct, [Last accessed on 2015 Jan 10]. p. 5. Available from: http://www.va.gov/painmanagement/docs/toolkit.pdf .

- 6.4th ed. Glenview, IL: American Pain Society; 1999. American Pain Society. Principles of Analgesic Use in the Treatment of Acute Pain and Cancer Pain. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coombes v Florio 450 Mass 182; 877 N.E.2d; Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts. 2007 Dec 10; [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rich B. Physicians’ legal duty to relieve suffering. [Last accessed on 2015 Jan 10];West J Med. 2001 175:151–2. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.175.3.151. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1071521/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). HCAHPS: Patients’ Perspectives of Care Survey. [Last accessed on 2015 Jan 10]. Available from: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-instruments/HospitalQualityInits/Downloads/HospitalHCAHPSFactSheet201007.pdf .

- 10.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). HCAHPS: Patients’ Perspectives of Care Survey. [Last accessed on 2015 Jan 10]. Available from: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/HospitalHCAHPS.html .

- 11.American College of Emergency Physicians. Emergency Visits Are Increasing, New Poll Finds; Many Patients Referred by Primary Care Doctors? [Last accessed on 2015 Jan 10]. Available from: http://www.acep.org/Contentasp?id=78646 .