Abstract

It is still debated whether microglia play a beneficial or harmful role in myelin disorders such as multiple sclerosis and leukodystrophies as well as in other pathological conditions of the central nervous system. The osteopetrotic (op/op) mouse has reduced numbers of cells of monocyte lineage as a result of an inactivating mutation in the colony stimulating factor-1 gene. To determine whether this mutant mouse might be used to study the role of microglia in myelin disorders, we quantified the number of microglia in the central nervous system of op/op mice and explored their ability to respond to brain injury created by a stab wound. Microglial density in the 2-month-old op/op mice was significantly decreased in the white matter tracts compared with the -ge matched wild-type controls (by 63.6% in the corpus callosum and 86.4% in the spinal dorsal column), whereas the decrease was less in the gray matter, cerebral cortex (24.0%). A similar decrease was seen at 7 months of age. Morphometric studies of spinal cord myelination showed that development of myelin was not affected in op/op mice. In response to a stab wound, the increase in the number of microglia/macrophages in op/op mice was significantly less pronounced than that in wild-type control. These findings demonstrate that this mutant is a valuable model in which to study roles of microglia/macrophages in the pathophysiology of myelin disorders.

Keywords: osteopetrotic mice, op/op mice, myelin

Microglia, the resident macrophages in the central nervous system (CNS), were originally described solely as phagocytes that clear cell debris in the CNS (reviewed in Rezaie and Male, 2002). However, as new functions of microglia and macrophages in the CNS have been discovered, the roles of these cells in various CNS pathophysiologies have become more complex and controversial (Diemel et al., 1998; Hanisch and Kettenmann, 2007; Nguyen et al., 2002; Popovich and Longbrake, 2008; Schwartz, 2003; Stoll et al., 2002). Primarily, microglia appear to function as immunocompetent cells of the CNS, initiating inflammation by secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, and IL-6 and by releasing free radicals such as nitric oxide (NO). In addition, the expression of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) II on these cells has indicated that these cells function as antigen presenting cells that initiate T lymphocyte-mediated immune response. These activities of microglia/macrophages were initially thought to be harmful to other cells of the CNS (e.g., neurons and oligodendrocytes). However, recent evidence suggests that microglia/macrophages may protect or promote the development and survival of neurons and oligodendrocytes. In myelin disorders, for example, microglia-derived molecules such as TNF-α (Arnett et al., 2001), IL-1β (Mason et al., 2001), and MHC II (Arnett et al., 2003) have been shown to promote remyelination in a mouse model of demyelination by stimulating proliferation of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. NO has been shown to be protective against apoptotic death of oligodendrocytes (Arnett et al., 2002). Moreover, depletion of macrophages delays CNS remyelination, perhaps via induction of insulinlike growth factor-1 and transforming growth factor-β1 expression in a rat model of chemically induced demyelination (Kotter et al., 2005). These studies suggest that the ability to modulate microglial function in vivo may be a key not only to controlling deleterious inflammation but to promoting successful myelin repair. Therefore, development of rodent models that lack microglial population in the white matter may help us understand the enigmatic nature of microglia/macrophages in the pathophysiology of myelin disorders such as multiple sclerosis and the leukodystrophies.

The osteopetrotic (op/op) mouse has reduced numbers of tissue macrophages (Cecchini et al., 1994; Wiktor-Jedrzejczak et al., 1992) as a result of an inactivating mutation in the colony stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1; also called macrophage colony-stimulating factor) gene (Wiktor-Jedrzejczak et al., 1990; Yoshida et al., 1990). However, previous reports have shown differing results regarding the alteration in the number of microglia in op/op mice. Some report that microglia develop normally in the brain (Blevins and Fedoroff, 1995; Chang et al., 1994), whereas others find a decrease in the number of microglia (Kondo et al., 2007; Sasaki et al., 2000; Węgiel et al., 1998). Moreover, changes in op/op microglia have not been known in the spinal cord, which is often severely affected in many animal models of myelin disorders and thus is being extensively studied.

In this study, we examined the number of microglia as detected immunohistochemically, both in the brain and spinal cord of op/op mice. Our focus was to determine whether the op/op mouse has reduced number of microglia in white matter tracts of the CNS. We also investigated the response of op/op microglia to tissue injury by creating a stab wound in the brain. Both the reduction in the number of microglia and their attenuated response to the stab wound in the white matter of op/op mice, together with the normal development of myelin shown in this study, lead us to propose that the op/op mouse is a useful model to explore the roles of microglia in the pathophysiology of various myelin disorders.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Breeding pairs of B6C3Fe-Csf1op/J mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and maintained at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Methods for animal husbandry, surgery, and sacrifice in this study were approved by the University’s Animal Care and Use Committee. The lack of incisors, as well as genotyping by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), described below, identified the mutant op/op mice. The op/op mutants were weaned at postnatal day (P)-16 and fed with liquid diet (L10012G, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) and powdered rodent diet (Harlan Tekrad, Madison, WI) in 35-mm plastic dish lids (Corning) placed on the cage floor. This early feeding with the liquid diet enabled 100% of op/op pups to survive beyond the weaning age (P21) and facilitated subsequent healthy growth of the mice. Very occasionally (3 out of 150 total op/op mice produced in our laboratory; unpublished data) op/op mice develop hydrocephalus around 4–8 weeks old (Marks and Lane, 1976) and such mice were excluded from the study.

PCR Diagnosis of the Csf1op Mutation

We diagnosed the Csf1op mutation by PCR analysis of genomic DNA originally described by Lieschke et al. (1994). The DNA samples were prepared from the tail tip between 4 and 10 days of age. The primers were: 5′-TGTGTCCCTTCCTCAGATTACA-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGTCTCATCTATTATGTCTTGTACCAGCCAAAA-3′ (antisense). The underline indicates a mismatch sequence. The PCR mixture (20 μl) contained 2.5 mM MgCl2, 125 μM of each dNTP, 100 nM of each primer, 10× PCR buffer (Promega, Madison, WI), 0.025 unit/μl of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega), and 2 μl of genomic DNA. The samples were denatured for 2 min at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 50°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec, and the final extension reaction at 72°C for 7 min. The PCR products were digested with 5 units of Bgl I at 37°C for 1 hr and resolved by electrophoresis on an 8% polyacrylamide gel. The digestion of PCR product yields distinctive patterns of bands for the wild-type (96 and 99 bp), heterozygote (70, 96, and 99 bp), and homozygote (70 and 96 bp).

Stab Wound Surgery

Under isoflurane anesthesia, 2-month old wild-type and op/op mice (n = 4, each group) were placed on a stereotaxic frame and, through a midline incision, a burr hole was made at 1 mm caudal to the bregma and 2 mm right from the mid-line. A stab wound was created by inserting a sterile 25-gauge needle 4 mm ventral from the surface of dura through the burr hole, encompassing the cerebral cortex and subcortical white matter. The needle was slowly withdrawn, the burr hole closed with bone wax, and the mice allowed to recover on a heating pad.

Tissue Preparation

After a lethal injection of sodium pentobarbital (120 mg/kg, i.p.), the animals were perfused transcardially with 10 mM phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB). The brains and spinal cords were removed, postfixed in the same fixative overnight, cryoprotected in 15% sucrose/PB over 48 hr, snap-frozen in powdered dry ice, cut on a cryostat at 20 μm, and used for free-floating immunohistochemistry.

Some spinal cord blocks were further fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PB after perfusion fixation, embedded in Epon plastic, and cut at 1 μm for toluidine blue myelin staining.

Mice that had a stab wound were perfusion-fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in PB (n = 3 per group). The brains were removed, postfixed in the same fixative for 30 min, cryoprotected overnight, and frozen with powdered dry ice. The brains were cut at 6 μm on the cryostat, mounted on glass slides, and used for slide-mounted immunohistochemistry.

Free-floating Immunohistochemistry

The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-Iba-1 polyclonal antibody (1:5,000; WAKO), rat anti-MBP antibody (1:1,000; Chemicon), and rabbit anti-rat GST-pi antibody (1:100,000; MBL). Endogenous peroxidase activity in sections was quenched with 0.5% H2O2 in 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline containing 0.3% Triton X-100 (PBS-T, pH 7.4) for 30 min. The sections were then incubated overnight with the primary antibodies, 90 min with donkey biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG or anti-rat IgG (1:1,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), and for 1 hr with the avidin-biotin peroxidase complex (1:2,000; Vector laboratories, Burlingame, CA). PBS-T was used for diluting above regents and washing sections between the procedures. Peroxidase activity was visualized with 0.02% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB), 20 mM imidazole and 0.0045% H2O2 in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.6). For negative control staining, the primary antibodies were omitted, and no staining was observed.

Slide-mounted Immunohistochemistry

Endogenous peroxidase activity in sections was quenched with 0.5% H2O2 in PBS-T for 30 min. The slide-mounted sections were first incubated with rabbit anti-Iba-1 polyclonal antibody (1:500) for 1 hr at room temperature, for 1 hr with donkey biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (1:100), and for 1 hr with the avidin-biotin peroxidase complex (1:200). The antibodies were diluted with PBS-T containing 10% normal donkey serum. The peroxidase activity was visualized as above.

Coronal sections from the brain (striatal level) and the cervical spinal cord from 2-month-old wild-type mice (perfusion-fixed with 2% PFA; n = 3) were double-immunostained for CD45 and CSF-1 receptor. The slides were incubated sequentially with rat anti-mouse CD45 antibody (1:500; Serotec, Raleigh, NC) and rabbit anti-CSF-1 receptor antibody (1:50; ab32633, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) for 1 hr for each antibody. Then the slides were incubated with a mixture of Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:100 in PBS-T, Molecular Probes) for 1 hr. These primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in PBS-T containing 10% normal goat serum. The air-dried slides were coverslipped with SlowFade anti-fade medium (Molecular Probes). Epifluorescence was observed and photographed with the SPOT CCD camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI) on the Nikon Eclipse E800M light microscope.

Morphometric Analyses

Quantitative analyses of microglia density

The number of Iba-1 immunolabeled microglia was counted in the parasagittal brain sections and spinal cord cross sections (20 μm thickness) from the wild-type and op/op mice at 2 and 7 months of age (three animals per group). Four sequential images were taken along the corpus callosum (white matter) level and the layer III of cerebral cortex (gray matter) at the striatal level through the 40× objective lens and SPOT CCD camera on the microscope. From the cross sections of the cervical spinal cord, 2 images were taken in the dorsal column (white matter) and the laminae IV–V (gray matter), bilaterally. From 2 randomly selected brain sections and 4 randomly selected spinal cord sections, total of 8 images were obtained for each area of interest per animal, and the number of Iba-1+ microglia with a hematoxylin-stained nucleus were counted in these images, each of which has the area of 0.062 μm2, and averaged.

The number of Iba-1+ microglia was also counted in sections (6 μm thickness) containing the stab wound. Two sections that contain the entire needle tract and were 300 μm apart rostrocaudally were selected for each animal (three animals per group). Two consecutive images both lateral and medial to the stab wound (4 images total) were photographed along the subcortical white matter tract as well as along the cortical layer III for the gray matter. To avoid counting macrophages directly infiltrated through the wound, the closest pictures were taken approximately 100 μm apart from the wound edge. Yet, some macrophages in the parenchyma might have been counted because they resemble phagocytic microglia. Perivascular macrophages were excluded from counting.

The effect of tissue volume changes on the measurement appeared negligible. For instance, there were no significant differences in the thickness of cerebral cortex between the wild-type and op/op mice (1443.2 ± 19.1 μm and 1,438.9 ± 38.6, respectively at 2 months old; 1494.6 ± 29.9 μm and 1,473.2 ± 34.1 μm, respectively at 7 months old; mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]; P > 0.5, Student’s t-test).

Quantitative analyses of myelination

To compare myelination in wild type and op/op mice, we analyzed the number of myelinated axons and the thickness of myelin on the toluidine blue-stained sections (n = 3 each group). Two rectangular areas (2,489 μm2 each) bilaterally adjacent to the ventral fissure of the spinal ventral column were photographed with the SPOT CCD camera through a 100× object lens plus 2× projection lens on the Nikon Eclipse E800M light microscope. The number of nonmyelinated and myelinated axons were counted in the two rectangles per animal. The G-ratios (axon diameter/total myelinated fiber diameter) were determined by MetaVue software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Only the myelinated axons in contact with two diagonal lines drawn on each rectangle were analyzed. When the axons were not exactly circular, the shortest diameter was measured.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with SigmaStat 3.1 (Systat Software, Point Richmond, CA). Data are presented as means ± SEM. Differences in the number of microglia between groups were assessed by one-way or two-way analysis of variance followed by Holm-Sidak post hoc test. Difference in axon densities between wild-type and op/op mice was determined by unpaired t-test. Differences in the measurement for myelin, axon, and g-ratio and fold changes in microglial density between wild-type and op/op mice were determined by the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Values of P < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Reduction in the Number OF Microglia in op/op Mice

To determine whether the number of microglia is reduced in op/op mice, we examined the number of Iba-1 immunoreactive microglia in sections from the brain and spinal cord of op/op mice and their wild-type littermates at 2 and 7 months of age. Iba-1+ microglia were diffusely distributed in all regions of the brain (Fig. 1) and the spinal cord (Fig. S1) at varied cell densities for both genotypes. Expression of Iba-1 faithfully overlapped with that of CD45, which is a sensitive marker for microglia/macrophages in the CNS (Sedgwick et al., 1991) (Fig. S2). Thus, Iba-1 immunoreactivity appeared to represent the whole population of microglia without being affected by the op/op phenotype or age.

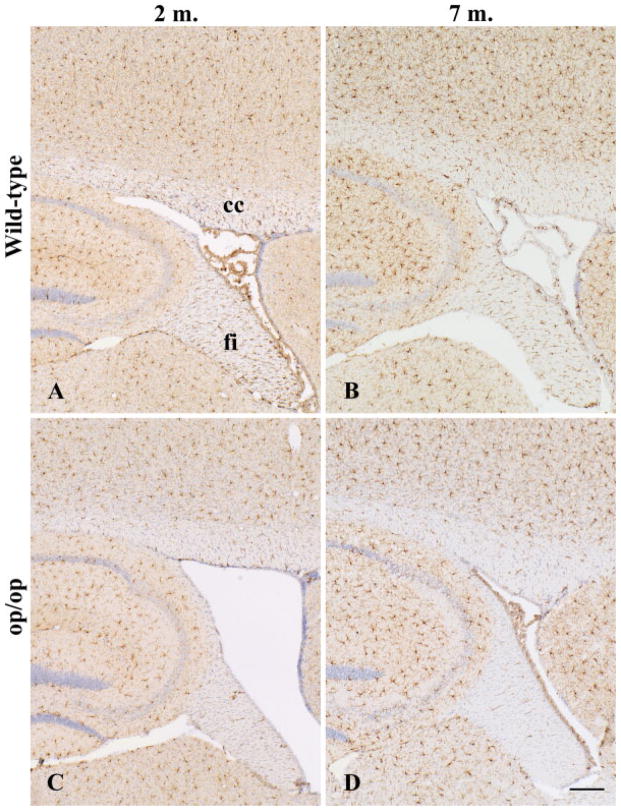

Fig. 1.

Iba-1+ microglia in the parasagittal sections of wild-type (A,B) and op/op (C,D) mouse brain at 2 (A,C) and 7 (B,D) months. Reduction in the number of microglia in op/op mice is pronounced in the white matter tracts such as corpus callosum (cc) and hippocampal fimbria (fi), although staining intensity appears to increase with age. Counterstained with hematoxylin. Scale bar = 200 μm.

Iba-1 immunohistochemistry revealed microglia in the gray matter radially extending several primary processes from a small round cell body with secondary–quaternary fine branches (Fig. 2A–D). In the white matter, the majority of microglia extend two primary branches from their spindle-shaped cell body along the axonal projection (Fig. 2E–H). There was no apparent difference in these morphologies of microglia between wild-type and op/op mice both at 2 and 7 months.

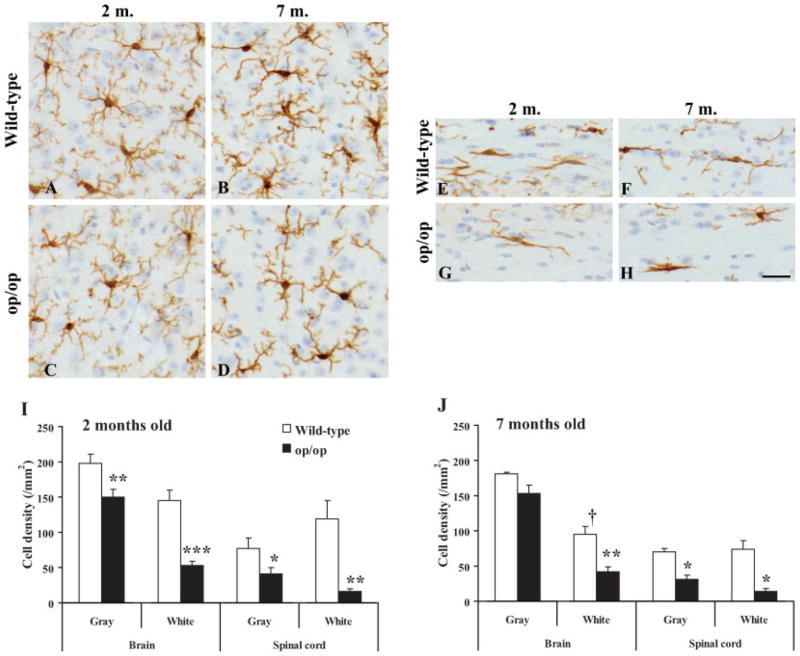

Fig. 2.

Iba-1+ microglia in the gray matter (layer III of cerebral cortex; A–D) and white matter (corpus callosum; E–H) of the parasagittal sections shown in Figure 1 at a higher magnification. There was no apparent difference between the wild-type (A,B,E,F) and op/op (C,D,G,H) mice in the morphology of microglia, including cell size and the appearance of processes. However, Iba-1 staining intensity was slightly higher in 7-month-old mice (B,D,F,H) than 2-month-old mice (A,C,E,G) both in the wild-type and op/op mice. Counterstained with hematoxylin. Scale bar = 25 μm. Changes in the number of Iba-1+ microglia in the brain and spinal cord of op/op mice at 2 (I) and 7 (J) months of age. In the brain, microglia were counted in the layer III of the cerebral cortex as the gray matter and in the corpus callosum as the white matter (n = 3 each group). In the spinal cord, microglia were counted in the layers III–VI of the gray matter and in the dorsal column as the white matter. Note that the reduction in the number of mutant microglia is more pronounced in the white matter. The levels of significance are as follows: ★P < 0.05, ★★P < 0.01, ★★★P < 0.001 (op/op vs. wild type); †significant difference (P = 0.012) against the young mouse control.

At 2 months old, the number of microglia was significantly decreased in op/op mice compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 2I). The difference was pronounced in the white matter, especially in the spinal cord (63.3% reduction in the corpus callosum and 86.4% in the spinal dorsal column, whereas 24.0% in the cerebral cortex and 47% in the spinal central gray matter). This significant reduction persisted at 7 months except for the brain gray matter (15.7% reduction but not significant) (Fig. 2B).

The Iba-1 immunoreactivity in individual microglial cells appeared to increase with age both in wild-type and op/op mice (Fig. 1–3). The number of Iba-1+ microglia was not affected by age except that there was a significant decrease (34.6% reduction, P < 0.05) with age in the corpus callosum of wild-type mice (Fig. 2).

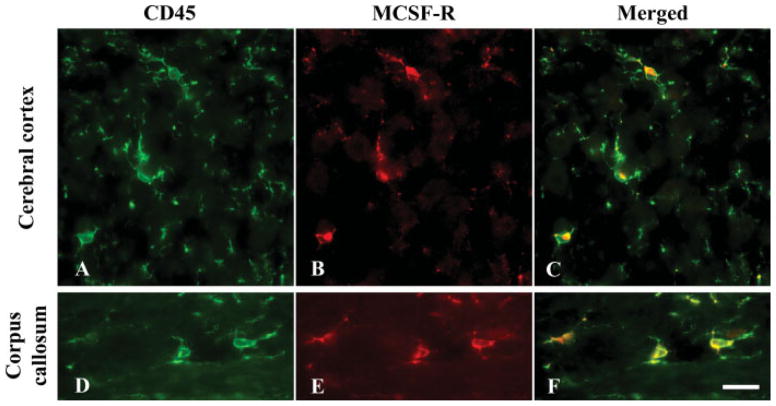

Fig. 3.

Double immunofluorescent staining for CD45 (A,D) and CSF-1 receptor (B,E) in the brain of 2-month-old wild-type mice. Merged images (C,F) show that CD45+ microglia always express CSF-1 receptor both in the gray (C) and white (F) matter. Scale bar = 20 μm.

Heterogeneity in CSF-1 Receptor Expression Was Not Found Between the Gray and White Matter

That the number of microglia in op/op mice is preferentially reduced in the white matter made us hypothesize that there might be subpopulations of microglia in the normal CNS regarding the expression of CSF-1 receptor and that there might be regional differences in its expression. However, double immunofluorescent staining showed that all microglia positive for CD45 (Fig. 3A, D) uniformly expressed CSF-1 receptor (Fig. 3B, E) both in the cerebral cortex (Fig. 3A–C) and corpus callosum (Fig. 3D–F) in 2-month-old wild-type mice. The CSF-1 receptor immunoreactivity in microglia was consistent in all other gray and white matter structures examined (coronal brain sections at the striatal level and cervical spinal cord cross sections; not shown).

Microglia in op/op Mice Are Less Reactive to the Stab Wound

Although the number of microglia was significantly reduced, there were still remaining populations of microglia in the CNS of op/op mice. To determine whether these microglia in op/op mice can respond to a pathologic insult, we created a stab wound in the brain of op/op mice and investigated the changes in the morphology and the number of microglia after injury.

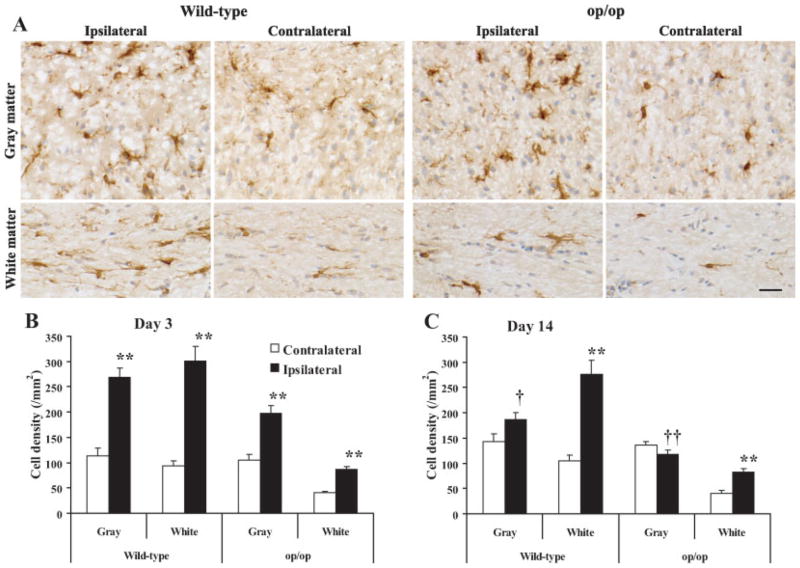

Three days after the stab wound, microglia in the ipsilateral hemisphere were activated both in the cerebral cortex and subcortical white matter of wild-type and op/op mice, showing strong Iba-1 immunoreactivity and hypertrophic cell bodies and processes (Fig. 4A). In contrast, microglia in the contralateral hemisphere remained quiescent (Fig. 4A). The number of microglia in the ipsilateral hemisphere significantly increased 3 days after the stab wound compared with that in the contralateral hemisphere (Fig. 4B). The extent of increase in the number was significantly less in op/op mice than wild-type mice (Table I). Fourteen days after the stab wound, the number of microglia in the ipsilateral gray matter was significantly reduced and returned to the level of contralateral hemisphere of both wild-type and op/op mice (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, however, the increase in the white matter was sustained in both groups at day 14 (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Reaction of microglia to the stab wound. A: Iba-1+ microglia in the ipsilateral and contralateral brain hemispheres 3 days after the stab wound surgery. Microglia in the ipsilateral hemisphere were activated. Besides the numbers of cells, the morphologies of microglia appeared similar between the wild-type and op/op mice. Counter-stained with hematoxylin. Scale bar = 25 μm. Changes in microglial density 3 days (B) and 14 days (C) after stab wound surgery in the brain. The number of Iba-1+ microglia was counted (n = 4 each group) in both the gray matter and white matter of the injured sites (ipsilateral) and the corresponding areas of intact hemisphere (contralateral); Significant difference (★★P < 0.001) against the contralateral region; significant differences (†P < 0.01 and ††P < 0.001) against 3 days after the wound.

TABLE I.

Fold Changes in Microglial Density After Stab Wound in the Brain★

| Brain matter | Day 3

|

Day 14

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | op/op | P value | Wild type | op/op | P value | |

| Gray | 2.36 ± 0.17 | 1.87 ± 0.15 | 0.0194 | 1.31 ± 0.10 | 0.87 ± 0.06 | 0.0194 |

| White | 3.22 ± 0.32 | 2.15 ± 0.13 | 0.0202 | 2.62 ± 0.26 | 2.05 ± 0.17 | 0.0814 |

Ratios of microglial density in the ipsilateral cerebral cortex and subcortical white matter over the density in the corresponding contralateral regions were calculated. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of n = 4 per group. Comparison was made between wild-type control and op/op mice by the Mann-Whitney rank sum test.

The op/op Mouse Forms Normal CNS Myelin

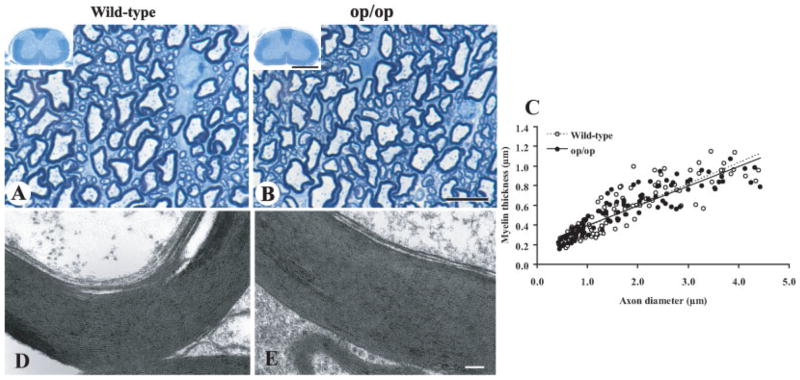

It is essential that op/op mice develop normal myelin in order for the mice to be used as a model to study white matter disorders. Thus, we evaluated the profiles of myelin and axons in the spinal cord of op/op mice. Toluidine blue myelin staining showed that wild-type and op/op mice had similar myelin formation in all white matter tracts (Fig. 5A,B). There was no significant difference in the density of axons, axon diameter, and myelin thickness between wild-type and op/op mice (Table II). The relationship between myelin thickness and axon diameter was similar in wild-type and op/op mice (Fig. 5C). The G-ratios (axon diameter/total myelinated fiber diameter) derived from these measurements were 0.607 ± 0.006 for the wild-type and 0.590 ± 0.006 for op/op mice.

Fig. 5.

Normal myelin development in op/op mice. Toluidine blue myelin staining shows a similar myelin profile in the ventral column of cervical spinal cord in wild-type (A) and op/op mice (B) at 45 days old. Insets are the entire view of the cord from which the high-power images were taken. Scale bars = 10 μm; and 1 mm for insets. (C) Correlation of axon diameter vs. myelin thickness was similar between wild-type and op/op mice at 45 days old. Diameters of axon and total myelinated fiber were scored from toluidine blue–stained ventral white matter of the spinal cord (n = 3 each group). Simple linear regression and the coefficient of determination (R2) were obtained as follows: y = 0.2169x + 0.1654, R2 = 0.7558 for wild-type mice; y = 0.1999x + 0.01952, R2 = 0.8056 for op/op mice. D,E: Representative electron micrographs of myelin in the ventral white matter of cervical spinal cord in the wild-type (D) and op/op (E) mice at 45 days old. Note that the axons are wrapped by multiple layers of compacted myelin with the similar periodicity in both phenotypes. Plastic-embedded sections cut at 80 nm were photographed with the Hitachi H-7600 electron microscope. Scale bar = 100 nm.

TABLE II.

Comparison of Myelin Profiles Between Wild-type and op/op Mice at 45 Days Old★

| Variable | Wild type | op/op | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Axon density (100 μm2) | 11.82 ± 0.37 | 11.74 ± 0.36 | 0.0804 |

| Axon diameter (μm) | 1.79 ± 0.10 | 1.65 ± 0.10 | 0.199 |

| Myelin thickness (μm) | 0.54 ± 0.03 | 0.53 ± 0.02 | 0.974 |

Data are obtained from the ventral white matter of toluidine blue–stained spinal cord sections (mean ± SEM, n = 3 each group).

In addition, immunohistochemistry for MBP and GST-pi showed similar appearance of myelination and number of oligodendrocytes in the brain, respectively, between wild-type and op/op mice (not shown). The ultrastructural integrity of myelin in op/op mice was comparable to that in the wild-type control (Fig. 5D,E).

DISCUSSION

Neurons and glial cells interact with each other to maintain the homeostasis of the CNS and respond to pathological insults. In myelin disorders, especially in demyelinating disorders, it is important to understand the interactions between microglia and oligodendrocytes and their myelin sheaths, as demyelinating lesions are generally accompanied by inflammation consisting of activation and/or accumulation of microglia and macrophages. To determine whether the CSF-1 deficient op/op mouse could be used as a future model in which to investigate the roles of microglia in the pathophysiology of myelin disorders, we have focused on the examinations of microglia and myelin development in the white matter of op/op mice and provided the following evidence. 1) The number of Iba-1 immunoreactive microglia was significantly decreased in the mutant, especially in the white matter of the brain and spinal cord up to 7 months of age. 2) Microglia in op/op mice were less reactive to the stab wound. 3) Despite the numerical and functional defects in microglia, op/op mice develop normal CNS myelin.

It is noteworthy that, although microglia have been reported to play a positive role in remyelination (Arnett et al., 2001, 2002, 2003; Kotter et al., 2005; Mason et al., 2001), the significant reduction in microglia number (86% in the spinal cord; Fig. 2) did not affect normal myelin development in the op/op mutant (Fig. 5). As demyelinated axons essentially reside in an inflammatory environment, perhaps proper regulation of inflammation by microglia, including clearance of myelin debris (reviewed in Neumann et al., 2009), is more important for effective remyelination rather than for normal myelin development.

The results of our study differ from two previous studies that reported that the number of microglia in op/op mice is comparable to that in normal control mice (Blevins and Fedoroff, 1995; Chang et al., 1994). These studies appeared to have investigated only the gray matter (cerebral cortex). This finding, to some extent, agrees to our study, in which the differences in the gray matter were much smaller with/without a statistical significance, compared with the differences in the white matter (Fig. 2).

Other in vivo models of microglia/macrophage depletion have been available to study the roles of these cells in myelin disorders. Dichloromethylene diphosphonate (Clodronate) encapsulated in liposomes, once ingested by macrophages, can effectively kill these cells in vivo (Van Rooijen, 1989), and has been used to study influence of microglia/macrophages on remyelination in rats (Kotter et al., 2001, 2005). Although the timing of macrophage depletion is controllable in this model, frequent intravenous injections of the drug are necessary for a long-term study.

Administration of ganciclovir arrests the function of microglia/macrophages in the mouse that carries the herpes simplex thymidine kinase transgene driven by the CD11b promoter (Heppner et al., 2005). In this model, this suicide gene could kill dividing CD11b hematopoietic cells. Thus, the mouse has to be rescued by transplantation of wild-type bone marrow cells followed by sublethal total body irradiation, which may modify the results via unwanted or unexpected CNS damages and repopulation of microglia derived from the bone-marrow cells.

The great advantage of using op/op mice, a naturally occurring mutant, is that microglia depletion can be achieved for the life of the mouse without any pharmacological treatments or genetic manipulations. However, some precautions must be taken. 1) A slightly low production rate of the mutant (14% of the litter) (Ramnaraine and Clohisy, 1998) may require maintenance of a relatively large mouse colony. 2) Potential modifications of the results may arise from their “osteopetrotic” phenotypes such as smaller size, lack of incisors (potential malnutrition), domed scull, and anemia in their earlier life (caused by narrowed bone marrow cavity) (Begg et al., 1993). These drawbacks, however, can readily be compensated by setting up proper control groups. 3) Recently, we have found spontaneous myelination failure in the optic nerve of op/op mice at the segment of stenotic optic canal, probably because of mechanical compression (manuscript in preparation). Similarly, other cranial nerves may need to be carefully examined for potential compression. 4) The peripheral immune functions may be altered in op/op mice as suggested by their monocytopenia and lymphocytopenia (Wiktor-Jedrzejczak et al., 1982) and a reduced severity in autoimmune glomerulonephritis on the Csf1op/op background (Lenda et al., 2004). Thus, when pathogenesis is the focus of study in immune-related CNS disorders such as experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE), involvement of peripheral immune system needs to be considered in addition to the reduction of microglial number in the CNS. However, we have observed that leukocyte infiltration is remarkably blocked in a mouse model of a leukodystrophy (unpublished data; discussed below) and EAE (unpublished data) on the Csf1op/op background. This feature makes the op/op mouse an ideal tool to investigate the CNS pathophysiology in the microglia-deficient environment without being influenced by the peripheral immunity.

Regional heterogeneity of microglia may be present as determined by their number and morphology (Lawson et al., 1990; Vela et al., 1995) or by molecular expression (Schmid et al., 2002). Thus, we hypothesized that if CSF-1 receptor was expressed on microglia differently between gray and white matter of normal mice, it may account for the preferential microglial defect in the white matter of op/op mouse. However, all CD45+ microglia homogenously expressed CSF-1 receptor in the normal brain, excluding such possibility (Fig. 3). Further studies are required to determine the molecular mechanisms by which microglial number is regionally controlled.

In addition to the significant reduction in the number of microglia in the white matter of op/op mice, the number of microglia in op/op mice increased to a lesser degree compared with that of wild-type mice in response to the stab wound (Fig. 4B,C). Interestingly, stab wound-induced morphological activation of individual microglial cells appeared similar between op/op and wild-type mice (Fig. 4A). Similarly, previous studies have demonstrated that the proliferation of microglia is impaired in the op/op mouse after cerebral ischemia (Berezovskaya et al., 1995), facial nerve axotomy (Raivich et al., 1994), and intrahippocampal injection of kinate (Rogove et al., 2002), while their activation is yet observed. Because a series of molecules work in concert to regulate microglial response (Kim and de Vellis, 2005) and the genetic deficiency of CSF-1 could have been compensated by other molecule or molecules in the op/op mouse, the results do not necessarily mean that CSF-1 is less important in microglial activation. CSF-1 may be more prerequisite for the proliferation of microglia in vivo. Nonetheless, the suppressed number of microglia in the white matter of the op/op mouse even after the injury will be the advantage to use it in future studies of white matter disorders.

The reason that op/op mice do not have a complete defect in microglia/macrophages is not known at present. Mice defective in two myeloid growth factors (CSF-1 and CSF-2) (Lieschke et al., 1994) or even three factors (CSF-3 in addition) (Hibbs et al., 2007) still retain some monocyte/macrophage populations. Further research, perhaps using genomic and proteomic approaches, may be necessary to identify molecule or molecules compensating for the development of myeloid cells in these mice. Nonetheless, the greatly reduced population of microglia in the white matter of op/op mice and their attenuated response to tissue injury suggest that the op/op mouse is a good model to study the function of microglia in the pathophysiology of white matter disorders such as multiple sclerosis and leukodystrophies. Given the 86% reduction in microglia number (Fig. 2), the spinal white matter in particular will be the suitable structure for this purpose. Indeed, the spinal white matter is severely affected in many mouse models of myelin disorders such as experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. An additional benefit is that the spinal cord is one of the best sites for quantitative studies of myelin. Recently, by cross-breeding with op/op mice, we were able to introduce macrophage depletion in the CNS of twitcher mice, a model of globoid cell leukodystrophy, in which massive accumulation of macrophages and activation of microglia in the white matter are the pathological hallmark (Y. Kondo and I. D. Duncan, 34th Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, San Diego, CA). This ongoing study will be of great significance in elucidating the roles of infiltrative macrophages in the pathophysiology of this fatal demyelinating disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Fahrenholtz, J. Ramaker, S. Martin, J. Adams, and L. Sherrington for technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH R01 NS055816, the Myelin Project, the Hunter’s Hope Foundation, and the Elizabeth Elser Doolittle Charitable Trust.

References

- Arnett HA, Mason J, Marino M, Suzuki K, Matsushima GK, Ting JP. TNFα promotes proliferation of oligodendrocyte progenitors and remyelination. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1116–1122. doi: 10.1038/nn738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett HA, Hellendall RP, Matsushima GK, Suzuki K, Laubach VE, Sherman P, Ting JP. The protective role of nitric oxide in a neurotoxicant-induced demyelinating model. J Immunol. 2002;168:427–433. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett HA, Wang Y, Matsushima GK, Suzuki K, Ting JP. Functional genomic analysis of remyelination reveals importance of inflammation in oligodendrocyte regeneration. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9824–9832. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-30-09824.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg SK, Radley JM, Pollard JW, Chisholm OT, Stanley ER, Bertoncello I. Delayed hematopoietic development in osteopetrotic (op/op) mice. J Exp Med. 1993;177:237–242. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.1.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezovskaya O, Maysinger D, Fedoroff S. The hematopoietic cytokine, colony-stimulating factor 1, is also a growth factor in the CNS: congenital absence of CSF-1 in mice results in abnormal microglial response and increased neuron vulnerability to injury. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1995;13:285–299. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(95)00013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins G, Fedoroff S. Microglia in colony-stimulating factor 1–deficient op/op mice. J Neurosci Res. 1995;40:535–544. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490400412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchini MG, Dominguez MG, Mocci S, Wetterwald A, Felix R, Fleisch H, Chisholm O, Hofstetter W, Pollard JW, Stanley ER. Role of colony stimulating factor-1 in the establishment and regulation of tissue macrophages during postnatal development of the mouse. Development. 1994;120:1357–1372. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.6.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Albright S, Lee F. Cytokines in the central nervous system: expression of macrophage colony stimulating factor and its receptor during development. J Neuroimmunol. 1994;52:9–17. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(94)90156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diemel LT, Copelman CA, Cuzner ML. Macrophages in CNS remyelination: friend or foe? Neurochem Res. 1998;23:341–347. doi: 10.1023/a:1022405516630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanisch UK, Kettenmann H. Microglia: active sensor and versatile effector cells in the normal and pathologic brain. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1387–1394. doi: 10.1038/nn1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppner FL, Greter M, Marino D, Falsig J, Raivich G, Hovelmeyer N, Waisman A, Rulicke T, Prinz M, Priller J, Becher B, Aguzzi A. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis repressed by microglial paralysis. Nat Med. 2005;11:146–152. doi: 10.1038/nm1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbs ML, Quilici C, Kountouri N, Seymour JF, Armes JE, Burgess AW, Dunn AR. Mice lacking three myeloid colony-stimulating factors (G-CSF, GM-CSF, and M-CSF) still produce macrophages and granulocytes and mount an inflammatory response in a sterile model of peritonitis. J Immunol. 2007;178:6435–6443. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SU, de Vellis J. Microglia in health and disease. J Neurosci Res. 2005;81:302–313. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo Y, Lemere CA, Seabrook TJ. Osteopetrotic (op/op) mice have reduced microglia, no Ab deposition, and no changes in dopaminergic neurons. J Neuroinflammation. 2007;4:31. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-4-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotter MR, Setzu A, Sim FJ, Van Rooijen N, Franklin RJ. Macrophage depletion impairs oligodendrocyte remyelination following lysolecithin-induced demyelination. Glia. 2001;35:204–212. doi: 10.1002/glia.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotter MR, Zhao C, van Rooijen N, Franklin RJ. Macrophage-depletion induced impairment of experimental CNS remyelination is associated with a reduced oligodendrocyte progenitor cell response and altered growth factor expression. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;18:166–175. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson LJ, Perry VH, Dri P, Gordon S. Heterogeneity in the distribution and morphology of microglia in the normal adult mouse brain. Neuroscience. 1990;39:151–170. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90229-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenda DM, Stanley ER, Kelley VR. Negative role of colony-stimulating factor-1 in macrophage, T cell, and B cell mediated autoimmune disease in MRL-Fas(lpr) mice. J Immunol. 2004;173:4744–4754. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.7.4744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieschke GJ, Stanley E, Grail D, Hodgson G, Sinickas V, Gall JA, Sinclair RA, Dunn AR. Mice lacking both macrophage- and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor have macrophages and coexistent osteopetrosis and severe lung disease. Blood. 1994;84:27–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks SC, Jr, Lane PW. Osteopetrosis, a new recessive skeletal mutation on chromosome 12 of the mouse. J Hered. 1976;67:11–18. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a108657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason JL, Suzuki K, Chaplin DD, Matsushima GK. Interleukin-1b promotes repair of the CNS. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7046–7052. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07046.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann H, Kotter MR, Franklin RJM. Debris clearance by microglia: an essential link between degeneration and regeneration. Brain. 2009;132:288–295. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen MD, Julien JP, Rivest S. Innate immunity: the missing link in neuroprotection and neurodegeneration? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:216–227. doi: 10.1038/nrn752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popovich PG, Longbrake EE. Can the immune system be harnessed to repair the CNS? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:481. doi: 10.1038/nrn2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raivich G, Moreno-Flores MT, Moller JC, Kreutzberg GW. Inhibition of posttraumatic microglial proliferation in a genetic model of macrophage colony–stimulating factor deficiency in the mouse. Eur J Neurosci. 1994;6:1615–1618. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramnaraine ML, Clohisy DR. Evaluation of mutant mouse production by mice that are heterogeneous for the Mcfsop gene. Lab Anim Sci. 1998;48:300–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezaie P, Male D. Mesoglia and microglia—a historical review of the concept of mononuclear phagocytes within the central nervous system. J Hist Neurosci. 2002;11:325–374. doi: 10.1076/jhin.11.4.325.8531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogove AD, Lu W, Tsirka SE. Microglial activation and recruitment, but not proliferation, suffice to mediate neurodegeneration. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:801–806. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki A, Yokoo H, Naito M, Kaizu C, Shultz LD, Nakazato Y. Effects of macrophage-colony-stimulating factor deficiency on the maturation of microglia and brain macrophages and on their expression of scavenger receptor. Neuropathology. 2000;20:134–142. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1789.2000.00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid CD, Sautkulis LN, Danielson PE, Cooper J, Hasel KW, Hilbush BS, Sutcliffe JG, Carson MJ. Heterogeneous expression of the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-2 on adult murine microglia. J Neurochem. 2002;83:1309–1320. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz M. Macrophages and microglia in central nervous system injury: are they helpful or harmful? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:385–394. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000061881.75234.5E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedgwick JD, Schwender S, Imrich H, Dorries R, Butcher GW, ter Meulen V. Isolation and direct characterization of resident microglial cells from the normal and inflamed central nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:7438–7442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll G, Jander S, Schroeter M. Detrimental and beneficial effects of injury-induced inflammation and cytokine expression in the nervous system. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;513:87–113. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0123-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooijen N. The liposome-mediated macrophage “suicide” technique. J Immunol Methods. 1989;124:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(89)90178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vela JM, Dalmau I, Gonzalez B, Castellano B. Morphology and distribution of microglial cells in the young and adult mouse cerebellum. J Comp Neurol. 1995;361:602–616. doi: 10.1002/cne.903610405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Węgiel J, Wiśniewski HM, Dziewįtkowski J, Tarnawski M, Kozielski R, Trenkner E, Wiktor-Jędrzejczak W. Reduced number and altered morphology of microglial cells in colony stimulating factor-1-deficient osteopetrotic op/op mice. Brain Res. 1998;804:135–139. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00618-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiktor-Jedrzejczak WW, Ahmed A, Szczylik C, Skelly RR. Hematological characterization of congenital osteopetrosis in op/op mouse. Possible mechanism for abnormal macrophage differentiation. J Exp Med. 1982;156:1516–1527. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.5.1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiktor-Jedrzejczak W, Bartocci A, Ferrante AW, Jr, Ahmed-Ansari A, Sell KW, Pollard JW, Stanley ER. Total absence of colony-stimulating factor 1 in the macrophage-deficient osteopetrotic (op/op) mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4828–4832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiktor-Jedrzejczak W, Ratajczak MZ, Ptasznik A, Sell KW, Ahmed-Ansari A, Ostertag W. CSF-1 deficiency in the op/op mouse has differential effects on macrophage populations and differentiation stages. Exp Hematol. 1992;20:1004–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H, Hayashi S, Kunisada T, Ogawa M, Nishikawa S, Okamura H, Sudo T, Shultz LD, Nishikawa S. The murine mutation osteopetrosis is in the coding region of the macrophage colony stimulating factor gene. Nature. 1990;345:442–444. doi: 10.1038/345442a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]