Abstract

The LTBPs (or latent transforming growth factor β binding proteins) are important components of the extracellular matrix (ECM) that interact with fibrillin microfibrils and have a number of different roles in microfibril biology. There are four LTBPs isoforms in the human genome (LTBP-1, -2, -3, and -4), all of which appear to associate with fibrillin and the biology of each isoform is reviewed here.

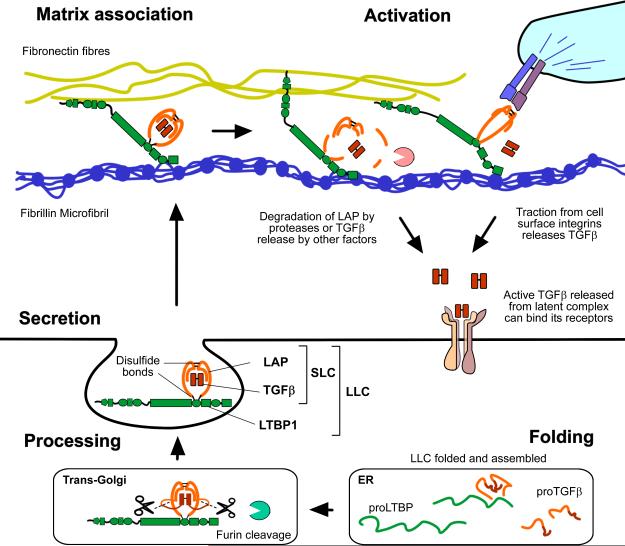

The LTBPs were first identified as forming latent complexes with TGFβ by covalently binding the TGFβ propeptide (LAP) via disulfide bonds in the endoplasmic reticulum. LAP in turn is cleaved from the mature TGFβ precursor in the trans golgi network but LAP and TGFβ remain strongly bound through non-covalent interactions. LAP, TGFβ, and LTBP together form the large latent complex (LLC). LTBPs were originally thought to primarily play a role in maintaining TGFβ latency and targeting the latent growth factor to the extracellular matrix (ECM), but it has also been shown that LTBP-1 participates in TGFβ activation by integrins and may also regulate activation by proteases and other factors. LTBP-3 appears to have a role in skeletal formation including tooth development. As well as having important functions in TGFβ regulation, TGFβ-independent activities have recently been identified for LTBP-2 and LTBP-4 in stabilizing microfibril bundles and regulating elastic fiber assembly.

Keywords: Latent TGFβ binding proteins, extracellular matrix, Latency associated protein, TGFβ activation

Introduction

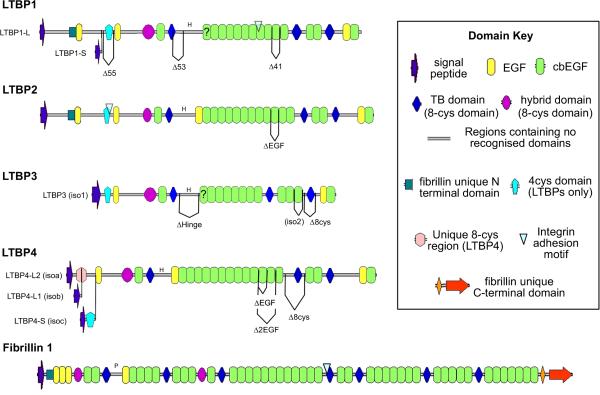

The LTBPs are a group of extracellular multi-domain proteins with several unique biological properties. They contain a number of modular domains including tandem arrays of calcium binding (cb) EGF (epidermal growth factor) domains that are interspersed with 8-Cys type domains that can be subcategorized into TGFβ-binding (TB) domains (although most of these domains do not actually bind TGFβ) and hybrid domains, which are very similar to TB domains in sequence and structure, but also contain some EGF-like features at their C-termini (Jensen et al. 2012).

Aside from LTBPs, the only other proteins that contain 8-Cys domains are the fibrillins. The fibrillins also contain cbEGF arrays and share some similarities in domain organization with the LTBPs (Figure 1). LTBP-1 and LTBP-2 also contain an N-terminal four cysteine domain that is similar in sequence to the fibrillin unique N-terminal domain (Yadin et al. 2013). However, LTBPs are clearly distinguishable from the fibrillins as they are shorter and have several regions of sequence with no disulfide bonds and no homology to known domains. These unstructured regions may introduce flexibility into these proteins (Robertson et al. 2011; Robertson et al. 2014).

Figure 1. The domain organization of the human LTBPs.

Domain symbols summarized in the key to the right of the figure. Some of the alternatively spliced forms of the LTBPs in humans are illustrated (Tsuji et al. 1990; Saharinen et al. 1999) and the domain structure of human Fibrillin-1 is also shown for comparison. The letter H denotes the “hinge” region in LTBPs, the letter P denotes the proline rich region in fibrillin-1.

All four LTBP isoforms associate with fibrillin microfibrils, and the C-termini of LTBP-1, -2 and -4 all interact with a similar region in the N-terminus of fibrillin-1 (Isogai et al. 2003; Ono et al. 2009; Massam-Wu et al. 2010). There appears to be no direct interaction between the LTBP-3 C-terminus and fibrillin-1 N-terminus in biochemical assays. However LTBP-3 co-localizes with fibrillin fibers in tissues and loss of fibrillin-1 in mice prevents matrix incorporation of LTBP-3, suggesting an important link with the microfibril (Zilberberg et al. 2012). LTBPs also bind other matrix components, such as fibronectin, ADAMTSL proteins, and the fibulins, and so have the potential to act as bridges between fibrillin fibers and other matrix proteins.

Fibrillins and fibrillin microfibrils have been detected and characterized in cnidarians (Reber-Muller et al. 1995), while LTBP-like sequences have so far only been detected in deuterostome genome sequences (a super-phylum containing sea urchins, lancelets, sea squirts and vertebrates), suggesting that LTBPs evolved later than the fibrillins, perhaps from a duplication of a fibrillin like gene that occurred after the deuterostome lineage split from the protostomes (insects, mollusks, nematodes) around 550 million years ago (Robertson and Rifkin 2013). This means LTBPs are unlikely to be essential components of the core microfibril structure (Robertson et al. 2011). However, microfibrils are crucial extracellular scaffolds that appear to have acquired additional functions through the course of evolution; functions for which LTBPs may now be essential.

LTBPs were discovered as part of a large latent complex with TGFβ and its propeptide (Kanzaki et al. 1990), and were given the name ‘latent TGFβ binding proteins’. The majority of these early studies pertained to LTBP-1, which forms a disulfide linked complex with the TGFβ propeptide (referred to as latency associated peptide or LAP) in the endoplasmic reticulum prior to secretion (Figure 2). TGFβ is cleaved from the TGFβ precursor inside the cell by furin proteases, but remains associated with LAP through strong non-covalent interactions. Association with LTBP may assist with proper folding of the TGFβ precursor protein (Brunner et al. 1989; Miyazono et al. 1991), aiding its secretion as well as directing its association with the ECM. The importance of this association is underscored when the cysteine in TGFβ1 LAP that is responsible for bonding LTBP (C33) is substituted with a serine in mice. These animals show inflammatory and tumorigenic phenotypes similar to those observed in TGFβ1 null mice (Yoshinaga et al. 2008). This suggests that covalent association of TGFβ1 LAP with LTBP (or an equivalent molecule) is important for extracellular TGFβ activity. One way in which LTBPs may contribute directly to TGFβ activity is by assisting integrin mediated latent TGFβ activation. LTBP-1 promotes activation by anchoring to the ECM and creating traction when LAP is bound by cell surface integrins, and this traction can deform LAP and release the active growth factor (Annes et al. 2004; Wipff et al. 2007; Buscemi et al. 2011). LTBPs may also have roles in other TGFβ activation processes though these mechanisms are less well understood.

Figure 2. Roles of LTBP-1 in TGFβ signaling.

LTBP-1 is folded and associates covalently with LAP via disulfide bonds while still inside the cell. This large latent complex (LLC) is then secreted and can associate with specific fibers in the ECM where TGFβ is held in a latent state. Latent TGFβ activation must then occur so that the growth factor can bind to it's receptors. Many different activation mechanisms have been described (Robertson and Rifkin 2013), and LTBP-1 may play a direct role in anchoring TGFβ for traction driven activation by integrins.

Although members of the TGFβ family are found in all metazoans, bona-fide TGFβ like proteins only appear in the deuterostomes, at the same time as the LTBPs, and the features of LTBP and LAP required for their covalent linkage are highly conserved (Robertson et al. 2011; Robertson and Rifkin 2013), suggesting the functions of LTBPs and TGFβ may have co-evolved. However, regulating TGFβ is not the sole function of the LTBP family, and whereas LTBP-1 and LTBP-3 appear to associate with all three TGFβ isoforms, LTBP-4 is reported to bind only TGFβ1 LAP and does so very inefficiently, whereas LTBP-2 does not bind any TGFβ isoform. TGFβ-independent roles have been identified for both LTBP-2 and 4 by in vivo studies, and other TGFβ-independent functions for the LTBPs may yet be discovered. Below we consider the properties of the individual LTBPs, both in vivo and in vitro.

LTBP-1

LTBP-1 is expressed in a variety of tissues and cell types (Davis et al. 2014), but expression is particularly abundant in heart, lung, spleen, kidney and stomach (Tsuji et al. 1990; Saharinen et al. 1999). A number of splice forms have been described for LTBP-1 including a short (LTBP-1S) and long (LTBP-1L) form that utilize different transcriptional start sites (Figure 1). Some unique properties have been ascribed to the different isoforms, for example LTBP-1L appears to bind the ECM more efficiently than LTBP-1S (Olofsson et al. 1995), but the significance of many LTBP-1 forms is not well understood.

As well as binding to the LAPs of all three TGFβ isoforms and interacting with fibrillin microfibrils via its C-terminus, the N-terminus of LTBP-1 also interacts with fibronectin (Dallas et al. 2005; Fontana et al. 2005; Kantola et al. 2008) and co-localizes with fibronectin fibers even when fibrillin is absent. LTBP-3 and 4 are dependent on fibrillin for ECM incorporation (Zilberberg et al. 2012) and incorporate into the ECM more slowly (Koli et al. 2005). The exact LTBP domains involved in binding fibronectin are unknown and this interaction is mediated by heparan sulfate proteoglycans (Chen et al. 2007). The fibronectin matrix is also important for latent TGFβ activation by αvβ6 integrin, as it may serve as a key anchorage point for the LLC in the ECM (Fontana et al. 2005), allowing traction to be generated between cell surface integrins and the ECM that distorts LAP to effect TGFβ release (Buscemi et al. 2011; Shi et al. 2011). Specific N-terminal regions of LTBP-1 are also required for this activation, although only a small section of the hinge region is required for activation when attached to a truncated LTBP-1 construct, whereas a larger fragment of the N-terminus is required to activate TGFβ bound to a larger and more native LTBP-1 construct (Annes et al. 2004). LTBP-1 is also cross-linked to the matrix by transglutaminase in a similar region (Nunes et al. 1997), and this may also be important for TGFβ activation. However, it has not been demonstrated whether LTBP-1 is cross-linked to fibronectin or some other matrix molecule. As well as fibrillin and fibronectin, LTBP-1 also interacts with ADAMTSL2 and 3 in surface plasmon resonance (SPR) studies (Sengle et al. 2012), IGFBP3 in a yeast 2 hybrid screen (Gui and Murphy 2003), fibulin-4 in SPR studies (Massam-Wu et al.), and heparin in solid phase assays (Chen et al. 2007).

The full significance of LTBP-1's activities in vivo is not clear and some contradiction appears in the literature; knocking out exons specific to the long form of LTBP-1 results in embryonic-lethal cardiovascular defects, including persistent truncus arteriosus and interrupted aortic arch, as well as hypoplastic endocardial cushions due to reduced epithelial mesenchymal transition in embryonic heart valve development (Todorovic et al. 2007; Todorovic et al. 2011). These studies also showed reductions in phosphorylated Smad proteins in affected tissues, indicating deficient TGFβ signaling might play a role in these defects. However, in another mouse study the first exon of LTBP-1 shared by both long and short isoforms was deleted, but these animals only had minor cranio-facial abnormalities and shortening of the long bones, but no cardiovascular abnormalities (Drews et al. 2008). The apparent explanation for this discrepancy between mouse models is that deletion of the first shared exon results in exon skipping that allows the production of near fully functional LTBP-1L (personal communication V Todorovic and (Todorovic and Rifkin 2012)).

At present no complete knockout of LTBP-1 has been published, but it is surprising that the general features of LTBP knockout animals and TGFβ knockout animals (Kulkarni et al. 1993; Kaartinen et al. 1995; Sanford et al. 1997; Taya et al. 1999; Dunker and Krieglstein 2002) do not overlap more clearly. This may suggest either notable redundancy between LTBP isoforms or that there are significant LTBP-independent mechanisms of TGFβ secretion and signaling that occur during development. A substantial amount of LTBP-1 can be secreted by cells without bound TGFβ and it also is possible that there are TGFβ-independent functions for this protein that have yet to be determined (Rifkin 2005).

LTBP-2

LTBP-2 is expressed abundantly in elastic tissues, including aorta and lung (Gibson et al. 1995). LTBP-2 is unique in the family as it is the only isoform that clearly does not bind to latent TGFβ (Saharinen and Keski-Oja 2000). It has been suggested therefore that LTBP-2 has functions that are independent of latent TGFβ storage and activation.

Like other LTBPs, LTBP-2 associates with ECM (Hyytiainen et al. 1998); LTBP-2 not only co-localizes with fibrillin microfibrils, but its deposition is dependent on preformed fibers of fibrillin-1 (Vehviläinen et al. 2009). Hirani et al. reported that C-terminal region of LTBP-2 interacts specifically with N-terminal region of fibrillin-1, and that its binding site on fibrillin-1 is the same or in close proximity to that for LTBP-1. They also showed that the binding affinity of LTBP-1 and -2 to fibrillin-1 is comparable and that they compete for the same binding site (Hirani et al. 2007). This led to a hypothesis that LTBP-2 might indirectly regulate the activation of TGFβ by releasing LTBP-1 from microfibrils.

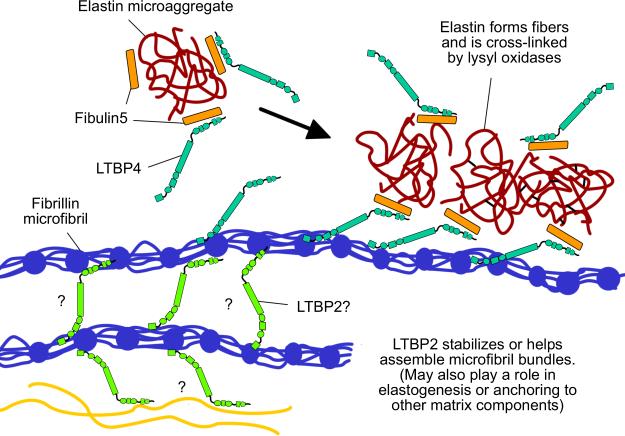

Electron microscopic examination revealed that LTBP-2 co-localizes with elastin-associated microfibrils (Gibson et al. 1995) and that LTBP-2 may have a role in the development of extracellular microfibrils and/or elastic fibers. Another major component of ECM with which LTBP-2 interacts is fibulin-5. Hirai et al. showed that the second four-cysteine domain in the N-terminal region of LTBP-2 specifically interacts with the sixth-calcium binding EGF domain of fibulin-5. Although LTBP-2 does not directly interact with elastin by itself, fibulin-5 does. Thus LTBP-2 can inhibit fibrillin-1-independent deposition of elastin and may facilitate the specific association of elastin and fibulin-5 with fibrillin-1 in fibroblast cultures (Hirai et al. 2007). In the periodontal membrane, LTBP-2 also controls the maturation of oxytalan fibers, which consist of elastin-free microfibril bundles, by regulating their coalescence through interaction with fibulin-5 (Tsuruga et al. 2012).

LTBP-2 binds to heparin and heparan sulfate proteoglycans through its N-terminus and, more weakly, through the central EGF repeat-rich region (Parsi et al. 2010). This interaction might help provide additional anchoring of microfibrils to basal membranes. A recent paper also suggested that LTBP-2 might negatively regulate elastogenesis in cultured ear cartilage cells through its interactions with fibulin-5, heparin, and elastin (Sideek et al. 2014).

LTBP-2 interacts with other members of the TGFβ family; including the pro-form of growth differentiating factor (GDF)8, also known as myostatin, pro-GDF11, and the proprotein convertase 5/6 (PC5/6) (Anderson et al. 2008; Sun et al. 2011). These observations suggest that LTBP-2 might influence the regulation of these growth factors, but its significance for their signaling in vivo is unclear. These interactions often occur within the endoplasmic reticulum; for example LTBP-2 preferentially associates with the un-glycosylated pro-form of GDF8 retained in cells (Anderson et al. 2008).

Investigation into the in vivo function of LTBP-2 was initially thought to be challenging because the first reported Ltbp2 null mice failed to develop past embryonic day 6.5 (Shipley et al. 2000), suggesting an indispensable role for LTBP-2 in early embryogenesis. However, there have been multiple recent reports of human patients bearing null mutations in LTBP2. These patients develop primary congenital glaucoma (PGC) (Ali et al. 2009), an autosomal recessive ocular disease with megalocornea, microspherophakia and lens dislocation with or without secondary glaucoma (Desir et al. 2010). A family with a mis-sense mutation in LTBP2 (V1177>M) has also been reported with Weill-Marchesani and Weill-Marchesani-like syndrome associated with ectopia lentis (Haji-Seyed-Javadi et al. 2012), although it is not clear how this change is deleterious to protein function. Interestingly patients with LTBP2 mutations clearly show no lethal birth defects or early developmental disorders. This discrepancy was not resolved until the recent report of new Ltbp2 null mice, in which the first exon was excised with minimum alterations in the genome (Inoue et al. 2014). These mice were viable and fertile without any gross abnormalities. The careful examination of these mice revealed that microfibrils of their ciliary zonules were fragmented and their lenses were dislocated. The authors also showed that the latter half of central cbEGF repeats of LTBP-2 binds to N-terminal fragment of fibrillin-1, and that the addition of recombinant LTBP-2 promotes the assembly of microfibril bundles in cultured cells and organ cultured eyeballs. These results highlight the role of LTBP-2 in the development of eye. However, the role of LTBP-2 in other tissues where it is strongly expressed, such as aorta and lungs, needs further investigation.

LTBP-2 may be a useful biomarker in certain clinical settings; LTBP-2 is expressed abundantly in lung, and its level in the serum of patients with acute dyspnoea may be a novel predictor of all-cause mortality (Breidthardt et al. 2012). LTBP-2 may also serve as a good biomarker of heart failure comparable to NT-proBNP (Bai et al. 2012), and single nucleotide polymorphisms in the LTBP-2 gene locus are associated with bone mineral density variation and prevalent fracture risk (Cheung et al. 2008).

LTBP-3

In humans LTBP-3 mRNA is expressed at high level in the heart, skeletal muscle, prostate and ovaries (Penttinen et al. 2002). The interaction of LTBP-3 with the ECM is far less well characterized than the interactions of the other LTBPs. To date, only fibrillin-1 has been identified as a protein in the ECM that is important for LTBP-3 incorporation, as absence of fibrillin-1 microfibrils both in vitro and in vivo prevents the incorporation of LTBP-3 into the ECM (Zilberberg et al. 2012). It is not known which specific domains of LTBP-3 and fibrillin-1 are involved in this interaction or if the interaction is mediated by a third partner.

Unlike LTBP-1, -2 and -4, LTBP-3 secretion is dependent on binding to LAP of one of the three TGFβ isoforms (Chen et al. 2002; Penttinen et al. 2002), making it less likely that LTBP-3 performs TGFβ-independent functions. Besides TGFβ, other proteins have been identified as binding partners of LTBP-3. One of these binding partners is GDF-8, another member of the TGFβ family and a key regulator of muscle mass. LTBP-3 interacts non-covalently with promyostatin early in the secretory pathway and following secretion, when LTBP-3 targets pro-GDF-8 to the ECM. LTBP-3 inhibits maturation of promyostatin into myostatin and thus may limit myostatin signaling. Ectopic expression of LTBP-3 in adult mouse muscles increases skeletal muscle fiber area and reduces myostatin-induced signaling (Anderson et al. 2008). Another study observed binding of LTBP-3 to proPC5/6A, a proprotein convertase. LTBP-3 interacts with proPC5/6A in the endoplasmic reticulum and targets/sequestrates it into the ECM as an inactive zymogen, preventing proPC5/6A conversion to the active convertase PC5/6A (Sun et al. 2011).

Although there is strong evidence that LTBP-1 plays an important role in protease and integrin-mediated latent TGFβ activation, no specific role for LTBP-3 in latent TGFβ activation has been described (Annes et al. 2004; Ge and Greenspan 2006; Gomez-Duran et al. 2006). In integrin-mediated latent TGFβ activation, LTBP-3 was unable to substitute for LTBP-1, suggesting that different mechanisms of activation may be involved (Annes et al. 2004). However, several lines of evidence suggest an important role for LTBP-3 in controlling TGFβ signaling; mice that lack LTBP-3 (Ltbp3−/−) have premature ossification of the skull base synchondroses, increased bone density and developmental emphysema, which are phenotypes consistent with decreased TGFβ signaling, as visualized by reduced pSmad staining in some tissues (Dabovic et al. 2002; Colarossi et al. 2005). In another study, knocking down Ltbp3 in zebrafish caused cardiovascular defects that phenocopy small-molecule inhibition of TGFβ signaling in these organisms, whereas expression of a constitutively active TGFβ type 1 receptor rescued these defects (Zhou et al. 2011). Taken together, absence of LTBP-3 in either mice or zebrafish attenuates TGFβ signaling.

Several specific roles have been described for LTBP-3 in human disease; a nonsense mutation (Y744X) in LTBP-3 was associated with oligondotia, which is a congenital tooth agenesis of six or more teeth and a common abnormality of human dentition. This autosomal-recessive mutation was also associated with short stature and was the first LTBP-3 mutation associated with a human disease (Noor et al. 2009).

In a recent study, Naba et al. defined the ECM signature of poorly and highly metastatic mammary carcinoma. They demonstrated that the presence of high levels of LTBP-3 protein is characteristic of particularly metastatic tumors and LTBP3 knockdown led to a significant inhibition of metastatic dissemination. This shows that LTBP-3 may play causative role in metastasis, and defines LTBP-3 as a potential therapeutic target (Naba et al. 2014). Although surprisingly in malignant mesothelioma knock down of LTBP3 appeared to lead to an increase in TGF-β signaling (Vehvilainen et al. 2010).

LTBP-3 and LTBP-1 may also work together to perform unique but related functions. An excellent example is the process of human mesenchymal stem cell differentiation to osteoblasts (Koli et al. 2008), in which LTBP-3 controls TGFβ levels early during the commitment phase, whereas LTBP-1 is involved in the subsequent maturation and mineralization phase.

LTBP-4

LTBP-4 is similar in domain structure to the other LTBPs and a number of alternative splice forms have been documented (Figure 1). These splice forms include a version lacking the TGFβ-binding 3rd 8-cys domain. Three different transcriptional start sites have been identified, one of which encodes LTBP-4S, where the 4-cysteine domain found in the other three LTBPs follows the signal peptide (blue pentagons in figure 1). The other two forms are termed LTBP-4L1 and LTBP-4L2, which contain an additional 4 or 8 cysteines respectively to the N-terminus, although this region of sequence has no detectable homology with other LTBPs or known protein domains.

Northern blots demonstrated LTBP4 expression in heart, skeletal muscle, pancreas, placenta, uterus, prostate, small intestine and lung (Giltay et al. 1997; Saharinen et al. 1998). LTBP-4 appears only to bind the TGFβ1 isoform, and it does so inefficiently (Saharinen and Keski-Oja 2000; Chen et al. 2005). Latent TGFβ is only bound to a small fraction of the LTBP-4S secreted by many cells (Saharinen and Keski-Oja 2000), although one report suggests that N-terminally extended LTBP-4L binds TGFβ more effectively (Kantola et al. 2010).

Inefficient binding of LTBP-4 to latent TGFβ might be explained by structure of the 3rd 8-Cys domain where several negatively charged residues involved in the interaction with LAP in LTBP-1 and –3 are absent in LTBP-4 (Saharinen and Keski-Oja 2000; Chen et al. 2005). The reduced negative charge may affect the initial docking of LAP residues and the disulfide exchange of the cysteine pair in the 8-Cys domain to form the LLC.

Ltbp4S knockout mice have severe defects including reduced terminal air sac septation in the lungs and rectal prolapse associated with deceased levels of TGFβ (Sterner-Kock et al. 2002). Human patients have also been described with homozygous null mutations in the LTBP4 gene, yielding Urban-Rifkin-Davis syndrome (URDS). These individuals suffer from disrupted pulmonary, gastrointestinal, urinary, musculoskeletal, craniofacial and dermal development (Sterner-Kock et al. 2002; Urban et al. 2009).

A study by Koli et al. on lung fibroblasts isolated from Ltbp4S−/− mice suggested that lack of LTBP-4 caused a decrease in the level of active TGF-β and an increase in expression of bone morphogenic protein (BMP)-4 (Koli et al. 2004). The authors speculated that because BMP-4 is essential for lung development, and its over expression produces abnormal lungs in mutant mice (Bellusci et al. 1996), the emphysema in Ltbp4S−/− mice might result from the switch from TGFβ to BMP-4 signaling.

The phenotypes of Ltbp4S knockout mice and URDS patients are consistent with disrupted elastic fiber assembly. In the absence of LTBP-4, elastin forms large aggregates adjacent to microfibrils instead of incorporating into microfibril bundles (Dabovic et al. 2009). The precise molecular mechanisms by which LTBP-4 regulates elastic fiber assembly are unclear but LTBP-4 interacts with fibulin-5 in vitro and in vivo and recombinant LTBP-4 enhances elastogenesis in human dermal fibroblast cultures (Noda et al. 2013). LTBP-4 also interacts with fibrillin (Isogai et al. 2003; Noda et al. 2013), therefore LTBP-4 might act as a bridge to target elastin-fibulin-5 complexes to fibrillin microfibrils and promote elastic fiber assembly (Figure 3).

Figure 3. TGFβ independent roles of LTBP-2 and LTBP-4.

LTBP-4 (turquoise in this figure) plays an important role in regulating elastogenesis. The hypothesized mechanism is that LTBP-4 binds fibulin-5 (orange) associated with elastin (dark red) and helps it specifically associate with the fibrillin microfibril (dark blue). It is not known whether in the ECM LTBP-4 first associates with fibrillin microfibrils or fibulin-5-elastin complexes, or both. Fibulin-5 may also bind to fibrillin independently of LTBP-4 but for simplicity this interaction is not shown (Ono et al. 2009). LTBP-2 (light green) is important for the formation and stability of microfibril bundles in mouse ciliary zonules. The precise interactions through which it performs this function are not clear but here LTBP-2 is drawn as serving a speculative bridging role for illustrative purposes.

In an attempt to answer the question whether LTBP-4 binding to TGFβ plays an important role in regulating TGFβ1 availability, Dabovic et al (2015) generated Ltbp4CC>SS mice in which the Ltbp4 gene was mutated to produce a form of LTBP-4 where the two cysteines (Cys 1235 and 1260) in the 8-Cys 3 domain that bind to latent TGFβ were substituted by serine residues. As previously mentioned, inhibition of the covalent association of TGFβ1 with LTBPs by introduction of a C33S substitution into the Tgfb1 gene yielded animals with a phenotype resembling TGFβ1 null mice (Yoshinaga et al. 2008), suggesting the importance of TGFβ LTBP complex formation for TGFβ1 function. Specific inhibition of LTBP-4 binding to TGFβ produces mice with no visable abnormalities suggesting that LTBP-4 has no TGFβ-dependent functions (Dabovic et al. 2015).

Interestingly, Fbln5−/−;Ltbp4S−/− double knockout mice recover some of the more severe defects seen in Ltbp4S−/− mice, such as defective alveolar septation, and their lungs resemble those of Fbln5−/− animals (Dabovic et al. 2015). LTBP-4 may control the rate of association between elastin-fibulin-5 complexes and microfibril bundles. Without LTBP-4 the uncontrolled aggregation of elastin-fibulin-5 complexes adjacent to the microfibril is more disruptive to lung development than the incorporation of elastin in the absence of both LTBP-4 and fibulin-5.

Although evidence is accumulating that LTBP-4 does not play a direct role in TGFβ regulation by binding LAP, TGFβ signaling still plays a significant role in the pathology of Ltbp4S−/− mice. When these mice were first described, reductions in TGFβ signaling were seen in some tissues (Sterner-Kock et al. 2002), but on further inspection increased TGFβ signaling was observed in the lungs (Dabovic et al. 2009). Reduced levels of TGFβ2 in Tgfβ 2−/−;Ltbp4S−/− mice rescued the defective alveolar septation but failed to restore normal elastic fiber formation (Dabovic et al. 2009). Reduction in TGFβ1 or 3 did not recover the defective alveolar septation (Dabovic et al. 2015), demonstrating that TGFβ2 is the isoform dysregulated in Ltbp4S−/− alveoli, either due to it's specific localization or other properties that make this growth factor uniquely sensitive to loss of LTBP-4.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Several predisposing genetic factors have been implicated in the pathogenesis of COPD including SNPs in the genes encoding TGFβ1 or LTBP4 (Celedon et al. 2004; Hersh et al. 2006). The Ltbp4S knockout mouse might be a good animal model of COPD, and Wempe et al reported that the inactivation of the antioxidant protein sestrin 2 (Sesn2) partially rescues the lung emphysema of Ltbp4S−/− mice (Wempe et al. 2010). That rescue is associated with activation of the TGF-β and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathways, and the authors speculated that Sesn2 antagonist could be clinically relevant to patients with COPD.

Summary

Here we have discussed how the LTBPs comprise a family of microfibril associated proteins with diverse functions related to TGFβ regulation, microfibril organization, and elastic fiber assembly. The size and complexity of these proteins introduces additional challenges when trying to study them and develop a complete understanding of their molecular functions. However, through careful analysis of in vivo and in vitro data we have begun to lift the veil on the complex associations between the LTBPs, the integrity of the ECM, and TGFβ signaling.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge funding from NIH grants R01 CA034282 (Regulation of TGF-β Activity in the Lung by LTBP-4) and P01 AR49698 (Cell Signaling in Marfan Syndrome).

References

- Ali M, McKibbin M, Booth A, Parry DA, Jain P, Riazuddin SA, Hejtmancik JF, Khan SN, Firasat S, Shires M, Gilmour DF, Towns K, Murphy A-L, Azmanov D, Tournev I, Cherninkova S, Jafri H, Raashid Y, Toomes C, Craig J, Mackey DA, Kalaydjieva L, Riazuddin S, Inglehearn CF. Null mutations in LTBP2 cause primary congenital glaucoma. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84(5):664–671. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SB, Goldberg AL, Whitman M. Identification of a novel pool of extracellular promyostatin in skeletal muscle. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283(11):7027–7035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706678200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annes JP, Chen Y, Munger JS, Rifkin DB. Integrin alphaVbeta6-mediated activation of latent TGF-beta requires the latent TGF-beta binding protein-1. J Cell Biol. 2004;165(5):723–734. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y, Zhang P, Zhang X, Huang J, Hu S, Wei Y. LTBP-2 acts as a novel marker in human heart failure - a preliminary study. Biomarkers. 2012;17(5):407–415. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2012.677860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellusci S, Henderson R, Winnier G, Oikawa T, Hogan BL. Evidence from normal expression and targeted misexpression that bone morphogenetic protein (Bmp-4) plays a role in mouse embryonic lung morphogenesis. Development. 1996;122(6):1693–1702. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.6.1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breidthardt T, Vanpoucke G, Potocki M, Mosimann T, Ziller R, Thomas G, Laroy W, Moerman P, Socrates T, Drexler B, Mebazaa A, Kas K, Mueller C. The novel marker LTBP2 predicts all-cause and pulmonary death in patients with acute dyspnoea. Clinical science (London, England : 1979) 2012;123(9):557–566. doi: 10.1042/CS20120058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner AM, Marquardt H, Malacko AR, Lioubin MN, Purchio AF. Site-directed mutagenesis of cysteine residues in the pro region of the transforming growth factor beta 1 precursor. Expression and characterization of mutant proteins. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(23):13660–13664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buscemi L, Ramonet D, Klingberg F, Formey A, Smith-Clerc J, Meister JJ, Hinz B. The single-molecule mechanics of the latent TGF-beta1 complex. Curr Biol. 2011;21(24):2046–2054. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celedon JC, Lange C, Raby BA, Litonjua AA, Palmer LJ, DeMeo DL, Reilly JJ, Kwiatkowski DJ, Chapman HA, Laird N, Sylvia JS, Hernandez M, Speizer FE, Weiss ST, Silverman EK. The transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGFB1) gene is associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(15):1649–1656. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Sivakumar P, Barley C, Peters DM, Gomes RR, Farach-Carson MC, Dallas SL. Potential role for heparan sulfate proteoglycans in regulation of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) by modulating assembly of latent TGF-beta-binding protein-1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(36):26418–26430. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703341200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Ali T, Todorovic V, O'Leary J M, Kristina Downing A, Rifkin DB. Amino acid requirements for formation of the TGF-beta-latent TGF-beta binding protein complexes. J Mol Biol. 2005;345(1):175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Dabovic B, Annes JP, Rifkin DB. Latent TGF-beta binding protein-3 (LTBP-3) requires binding to TGF-beta for secretion. FEBS Lett. 2002;517(1-3):277–280. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02648-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung C-L, Sham PC, Chan V, Paterson AD, Luk KDK, Kung AWC. Identification of LTBP2 on chromosome 14q as a novel candidate gene for bone mineral density variation and fracture risk association. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2008;93(11):4448–4455. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colarossi C, Chen Y, Obata H, Jurukovski V, Fontana L, Dabovic B, Rifkin DB. Lung alveolar septation defects in Ltbp-3-null mice. Am J Pathol. 2005;167(2):419–428. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62986-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabovic B, Chen Y, Choi J, Vassallo M, Dietz HC, Ramirez F, von Melchner H, Davis EC, Rifkin DB. Dual functions for LTBP in lung development: LTBP-4 independently modulates elastogenesis and TGF-beta activity. J Cell Physiol. 2009;219(1):14–22. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabovic B, Chen Y, Colarossi C, Obata H, Zambuto L, Perle MA, Rifkin DB. Bone abnormalities in latent TGF-[beta] binding protein (Ltbp)-3-null mice indicate a role for Ltbp-3 in modulating TGF-[beta] bioavailability. J Cell Biol. 2002;156(2):227–232. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200111080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabovic B, Robertson IB, Zilberberg L, Vassallo M, Davis EC, Rifkin DB. Function of Latent TGFβ Binding Protein 4 and Fibulin 5 in Elastogenesis and Lung Development. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2015;230(1):226–236. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallas SL, Sivakumar P, Jones CJ, Chen Q, Peters DM, Mosher DF, Humphries MJ, Kielty CM. Fibronectin regulates latent transforming growth factor-beta (TGF beta) by controlling matrix assembly of latent TGF beta-binding protein-1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(19):18871–18880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MR, Andersson R, Severin J, de Hoon M, Bertin N, Baillie JK, Kawaji H, Sandelin A, Forrest AR, Summers KM. Transcriptional profiling of the human fibrillin/LTBP gene family, key regulators of mesenchymal cell functions. Mol Genet Metab. 2014;112(1):73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desir J, Sznajer Y, Depasse F, Roulez F, Schrooyen M, Meire F, Abramowicz M. LTBP2 null mutations in an autosomal recessive ocular syndrome with megalocornea, spherophakia, and secondary glaucoma. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18(7):761–767. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drews F, Knobel S, Moser M, Muhlack KG, Mohren S, Stoll C, Bosio A, Gressner AM, Weiskirchen R. Disruption of the latent transforming growth factor-beta binding protein-1 gene causes alteration in facial structure and influences TGF-beta bioavailability. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783(1):34–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunker N, Krieglstein K. Tgfbeta2 −/− Tgfbeta3 −/− double knockout mice display severe midline fusion defects and early embryonic lethality. Anat Embryol (Berl) 2002;206(1-2):73–83. doi: 10.1007/s00429-002-0273-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana L, Chen Y, Prijatelj P, Sakai T, Fassler R, Sakai LY, Rifkin DB. Fibronectin is required for integrin alphavbeta6-mediated activation of latent TGF-beta complexes containing LTBP-1. FASEB J. 2005;19(13):1798–1808. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4134com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge G, Greenspan DS. BMP1 controls TGFbeta1 activation via cleavage of latent TGFbeta-binding protein. J Cell Biol. 2006;175(1):111–120. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson MA, Hatzinikolas G, Davis EC, Baker E, Sutherland GR, Mecham RP. Bovine latent transforming growth factor beta 1-binding protein 2: molecular cloning, identification of tissue isoforms, and immunolocalization to elastin-associated microfibrils. Molecular and cellular biology. 1995;15(12):6932–6942. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giltay R, Kostka G, Timpl R. Sequence and expression of a novel member (LTBP-4) of the family of latent transforming growth factor-beta binding proteins. FEBS Lett. 1997;411(2-3):164–168. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00685-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Duran A, Mulero-Navarro S, Chang X, Fernandez-Salguero PM. LTBP-1 blockade in dioxin receptor-null mouse embryo fibroblasts decreases TGF-beta activity: Role of extracellular proteases plasmin and elastase. J Cell Biochem. 2006;97(2):380–392. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui Y, Murphy LJ. Interaction of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 with latent transforming growth factor-beta binding protein-1. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;250(1-2):189–195. doi: 10.1023/a:1024990409102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haji-Seyed-Javadi R, Jelodari-Mamaghani S, Paylakhi SH, Yazdani S, Nilforushan N, Fan JB, Klotzle B, Mahmoudi MJ, Ebrahimian MJ, Chelich N, Taghiabadi E, Kamyab K, Boileau C, Paisan-Ruiz C, Ronaghi M, Elahi E. LTBP2 mutations cause Weill-Marchesani and Weill-Marchesani-like syndrome and affect disruptions in the extracellular matrix. Hum Mutat. 2012;33(8):1182–1187. doi: 10.1002/humu.22105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh CP, Demeo DL, Lazarus R, Celedon JC, Raby BA, Benditt JO, Criner G, Make B, Martinez FJ, Scanlon PD, Sciurba FC, Utz JP, Reilly JJ, Silverman EK. Genetic association analysis of functional impairment in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(9):977–984. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1452OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai M, Horiguchi M, Ohbayashi T, Kita T, Chien KR, Nakamura T. Latent TGF-beta-binding protein 2 binds to DANCE/fibulin-5 and regulates elastic fiber assembly. EMBO J. 2007;26(14):3283–3295. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirani R, Hanssen E, Gibson MA. LTBP-2 specifically interacts with the amino-terminal region of fibrillin-1 and competes with LTBP-1 for binding to this microfibrillar protein. Matrix biology : journal of the International Society for Matrix Biology. 2007;26(4):213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyytiainen M, Taipale J, Heldin CH, Keski-Oja J. Recombinant latent transforming growth factor beta-binding protein 2 assembles to fibroblast extracellular matrix and is susceptible to proteolytic processing and release. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273(32):20669–20676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Ohbayashi T, Fujikawa Y, Yoshida H, Akama TO, Noda K, Horiguchi M, Kameyama K, Hata Y, Takahashi K, Kusumoto K, Nakamura T. Latent TGF-beta binding protein-2 is essential for the development of ciliary zonule microfibrils. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(21):5672–5682. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isogai Z, Ono RN, Ushiro S, Keene DR, Chen Y, Mazzieri R, Charbonneau NL, Reinhardt DP, Rifkin DB, Sakai LY. Latent transforming growth factor beta-binding protein 1 interacts with fibrillin and is a microfibril-associated protein. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(4):2750–2757. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209256200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen SA, Robertson IB, Handford PA. Dissecting the fibrillin microfibril: structural insights into organization and function. Structure. 2012;20(2):215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaartinen V, Voncken JW, Shuler C, Warburton D, Bu D, Heisterkamp N, Groffen J. Abnormal lung development and cleft palate in mice lacking TGF-beta 3 indicates defects of epithelial-mesenchymal interaction. Nat Genet. 1995;11(4):415–421. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantola AK, Keski-Oja J, Koli K. Fibronectin and heparin binding domains of latent TGF-beta binding protein (LTBP)-4 mediate matrix targeting and cell adhesion. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314(13):2488–2500. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantola AK, Ryynanen MJ, Lhota F, Keski-Oja J, Koli K. Independent regulation of short and long forms of latent TGF-beta binding protein (LTBP)-4 in cultured fibroblasts and human tissues. J Cell Physiol. 2010;223(3):727–736. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanzaki T, Olofsson A, Moren A, Wernstedt C, Hellman U, Miyazono K, Claesson-Welsh L, Heldin CH. TGF-beta 1 binding protein: a component of the large latent complex of TGF-beta 1 with multiple repeat sequences. Cell. 1990;61(6):1051–1061. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90069-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koli K, Hyytiainen M, Ryynanen MJ, Keski-Oja J. Sequential deposition of latent TGF-beta binding proteins (LTBPs) during formation of the extracellular matrix in human lung fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res. 2005;310(2):370–382. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koli K, Ryynanen MJ, Keski-Oja J. Latent TGF-beta binding proteins (LTBPs)-1 and -3 coordinate proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Bone. 2008;43(4):679–688. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koli K, Wempe F, Sterner-Kock A, Kantola A, Komor M, Hofmann WK, von Melchner H, Keski-Oja J. Disruption of LTBP-4 function reduces TGF-beta activation and enhances BMP-4 signaling in the lung. J Cell Biol. 2004;167(1):123–133. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni AB, Huh CG, Becker D, Geiser A, Lyght M, Flanders KC, Roberts AB, Sporn MB, Ward JM, Karlsson S. Transforming growth factor beta 1 null mutation in mice causes excessive inflammatory response and early death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(2):770–774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massam-Wu T, Chiu M, Choudhury R, Chaudhry SS, Baldwin AK, McGovern A, Baldock C, Shuttleworth CA, Kielty CM. Assembly of fibrillin microfibrils governs extracellular deposition of latent TGF beta. J Cell Sci. 123(Pt 17):3006–3018. doi: 10.1242/jcs.073437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massam-Wu T, Chiu M, Choudhury R, Chaudhry SS, Baldwin AK, McGovern A, Baldock C, Shuttleworth CA, Kielty CM. Assembly of fibrillin microfibrils governs extracellular deposition of latent TGF beta. J Cell Sci. 2010;123(Pt 17):3006–3018. doi: 10.1242/jcs.073437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazono K, Olofsson A, Colosetti P, Heldin CH. A role of the latent TGF-beta 1-binding protein in the assembly and secretion of TGF-beta 1. EMBO J. 1991;10(5):1091–1101. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08049.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naba A, Clauser KR, Lamar JM, Carr SA, Hynes RO. Extracellular matrix signatures of human mammary carcinoma identify novel metastasis promoters. Elife. 2014;3:e01308. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda K, Dabovic B, Takagi K, Inoue T, Horiguchi M, Hirai M, Fujikawa Y, Akama TO, Kusumoto K, Zilberberg L, Sakai LY, Koli K, Naitoh M, von Melchner H, Suzuki S, Rifkin DB, Nakamura T. Latent TGF-beta binding protein 4 promotes elastic fiber assembly by interacting with fibulin-5. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(8):2852–2857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215779110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noor A, Windpassinger C, Vitcu I, Orlic M, Rafiq MA, Khalid M, Malik MN, Ayub M, Alman B, Vincent JB. Oligodontia is caused by mutation in LTBP3, the gene encoding latent TGF-beta binding protein 3. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84(4):519–523. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes I, Gleizes PE, Metz CN, Rifkin DB. Latent transforming growth factor-beta binding protein domains involved in activation and transglutaminase-dependent cross-linking of latent transforming growth factor-beta. J Cell Biol. 1997;136(5):1151–1163. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.5.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson A, Ichijo H, Moren A, ten Dijke P, Miyazono K, Heldin CH. Efficient association of an amino-terminally extended form of human latent transforming growth factor-beta binding protein with the extracellular matrix. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(52):31294–31297. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono RN, Sengle G, Charbonneau NL, Carlberg V, Bachinger HP, Sasaki T, Lee-Arteaga S, Zilberberg L, Rifkin DB, Ramirez F, Chu ML, Sakai LY. Latent transforming growth factor beta-binding proteins and fibulins compete for fibrillin-1 and exhibit exquisite specificities in binding sites. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(25):16872–16881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809348200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsi MK, Adams JRJ, Whitelock J, Gibson MA. LTBP-2 has multiple heparin/heparan sulfate binding sites. Matrix biology : journal of the International Society for Matrix Biology. 2010;29(5):393–401. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penttinen C, Saharinen J, Weikkolainen K, Hyytiainen M, Keski-Oja J. Secretion of human latent TGF-beta-binding protein-3 (LTBP-3) is dependent on co-expression of TGF-beta. J Cell Sci. 2002;115(Pt 17):3457–3468. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.17.3457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reber-Muller S, Spissinger T, Schuchert P, Spring J, Schmid V. An extracellular matrix protein of jellyfish homologous to mammalian fibrillins forms different fibrils depending on the life stage of the animal. Dev Biol. 1995;169(2):662–672. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifkin DB. Latent transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) binding proteins: orchestrators of TGF-beta availability. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(9):7409–7412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson I, Jensen S, Handford P. TB domain proteins: evolutionary insights into the multifaceted roles of fibrillins and LTBPs. Biochem J. 2011;433(2):263–276. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson IB, Handford PA, Redfield C. NMR spectroscopic and bioinformatic analyses of the LTBP1 C-terminus reveal a highly dynamic domain organisation. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e87125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson IB, Rifkin DB. Unchaining the beast; insights from structural and evolutionary studies on TGFbeta secretion, sequestration, and activation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013;24(4):355–372. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saharinen J, Hyytiainen M, Taipale J, Keski-Oja J. Latent transforming growth factor-beta binding proteins (LTBPs)--structural extracellular matrix proteins for targeting TGF-beta action. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1999;10(2):99–117. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(99)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saharinen J, Keski-Oja J. Specific sequence motif of 8-Cys repeats of TGF-beta binding proteins, LTBPs, creates a hydrophobic interaction surface for binding of small latent TGF-beta. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11(8):2691–2704. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.8.2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saharinen J, Taipale J, Monni O, Keski-Oja J. Identification and characterization of a new latent transforming growth factor-beta-binding protein, LTBP-4. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(29):18459–18469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford LP, Ormsby I, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Sariola H, Friedman R, Boivin GP, Cardell EL, Doetschman T. TGFbeta2 knockout mice have multiple developmental defects that are non-overlapping with other TGFbeta knockout phenotypes. Development. 1997;124(13):2659–2670. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.13.2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengle G, Tsutsui K, Keene DR, Tufa SF, Carlson EJ, Charbonneau NL, Ono RN, Sasaki T, Wirtz MK, Samples JR, Fessler LI, Fessler JH, Sekiguchi K, Hayflick SJ, Sakai LY. Microenvironmental regulation by fibrillin-1. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(1):e1002425. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi M, Zhu J, Wang R, Chen X, Mi L, Walz T, Springer TA. Latent TGF-beta structure and activation. Nature. 2011;474(7351):343–349. doi: 10.1038/nature10152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibahara K, Ota M, Horiguchi M, Yoshinaga K, Melamed J, Rifkin DB. Production of gastrointestinal tumors in mice by modulating latent TGF-beta1 activation. Cancer research. 2013;73(1):459–468. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipley JM, Mecham RP, Maus E, Bonadio J, Rosenbloom J, McCarthy RT, Baumann ML, Frankfater C, Segade F, Shapiro SD. Developmental expression of latent transforming growth factor beta binding protein 2 and its requirement early in mouse development. Molecular and cellular biology. 2000;20(13):4879–4887. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.13.4879-4887.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sideek MA, Menz C, Parsi MK, Gibson MA. LTBP-2 competes with tropoelastin for binding to fibulin-5 and heparin, and is a negative modulator of elastinogenesis. Matrix biology : journal of the International Society for Matrix Biology. 2014;34:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterner-Kock A, Thorey IS, Koli K, Wempe F, Otte J, Bangsow T, Kuhlmeier K, Kirchner T, Jin S, Keski-Oja J, von Melchner H. Disruption of the gene encoding the latent transforming growth factor-beta binding protein 4 (LTBP-4) causes abnormal lung development, cardiomyopathy, and colorectal cancer. Genes Dev. 2002;16(17):2264–2273. doi: 10.1101/gad.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Essalmani R, Susan-Resiga D, Prat A, Seidah NG. Latent transforming growth factor beta-binding proteins-2 and -3 inhibit the proprotein convertase 5/6A. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(33):29063–29073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.242479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taya Y, O'Kane S, Ferguson MW. Pathogenesis of cleft palate in TGF-beta3 knockout mice. Development. 1999;126(17):3869–3879. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorovic V, Finnegan E, Freyer L, Zilberberg L, Ota M, Rifkin DB. Long form of latent TGF-beta binding protein 1 (Ltbp1L) regulates cardiac valve development. Dev Dyn. 2011;240(1):176–187. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorovic V, Frendewey D, Gutstein DE, Chen Y, Freyer L, Finnegan E, Liu F, Murphy A, Valenzuela D, Yancopoulos G, Rifkin DB. Long form of latent TGF-beta binding protein 1 (Ltbp1L) is essential for cardiac outflow tract septation and remodeling. Development. 2007;134(20):3723–3732. doi: 10.1242/dev.008599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorovic V, Rifkin DB. LTBPs, more than just an escort service. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113(2):410–418. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji T, Okada F, Yamaguchi K, Nakamura T. Molecular cloning of the large subunit of transforming growth factor type beta masking protein and expression of the mRNA in various rat tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(22):8835–8839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.22.8835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuruga E, Oka K, Hatakeyama Y, Isokawa K, Sawa Y. Latent transforming growth factor-beta binding protein 2 negatively regulates coalescence of oxytalan fibers induced by stretching stress. Connect Tissue Res. 2012;53(6):521–527. doi: 10.3109/03008207.2012.702816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban Z, Hucthagowder V, Schurmann N, Todorovic V, Zilberberg L, Choi J, Sens C, Brown CW, Clark RD, Holland KE, Marble M, Sakai LY, Dabovic B, Rifkin DB, Davis EC. Mutations in LTBP4 cause a syndrome of impaired pulmonary, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, musculoskeletal, and dermal development. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85(5):593–605. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vehviläinen P, Hyytiäinen M, Keski-Oja J. Matrix association of latent TGF-beta binding protein-2 (LTBP-2) is dependent on fibrillin-1. Journal of cellular physiology. 2009;221(3):586–593. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vehvilainen P, Koli K, Myllarniemi M, Lindholm P, Soini Y, Salmenkivi K, Kinnula VL, Keski-Oja J. Latent TGF-beta binding proteins (LTBPs) 1 and 3 differentially regulate transforming growth factor-beta activity in malignant mesothelioma. Hum Pathol. 2010;42(2):269–278. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wempe F, De-Zolt S, Koli K, Bangsow T, Parajuli N, Dumitrascu R, Sterner-Kock A, Weissmann N, Keski-Oja J, von Melchner H. Inactivation of sestrin 2 induces TGF-beta signaling and partially rescues pulmonary emphysema in a mouse model of COPD. Dis Model Mech. 2010;3(3-4):246–253. doi: 10.1242/dmm.004234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wipff PJ, Rifkin DB, Meister JJ, Hinz B. Myofibroblast contraction activates latent TGF-beta1 from the extracellular matrix. J Cell Biol. 2007;179(6):1311–1323. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadin DA, Robertson IB, McNaught-Davis J, Evans P, Stoddart D, Handford PA, Jensen SA, Redfield C. Structure of the fibrillin-1 N-terminal domains suggests that heparan sulfate regulates the early stages of microfibril assembly. Structure. 2013;21(10):1743–1756. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshinaga K, Obata H, Jurukovski V, Mazzieri R, Chen Y, Zilberberg L, Huso D, Melamed J, Prijatelj P, Todorovic V, Dabovic B, Rifkin DB. Perturbation of transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta1 association with latent TGF-beta binding protein yields inflammation and tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(48):18758–18763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805411105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Cashman TJ, Nevis KR, Obregon P, Carney SA, Liu Y, Gu A, Mosimann C, Sondalle S, Peterson RE, Heideman W, Burns CE, Burns CG. Latent TGF-beta binding protein 3 identifies a second heart field in zebrafish. Nature. 2011;474(7353):645–648. doi: 10.1038/nature10094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilberberg L, Todorovic V, Dabovic B, Horiguchi M, Courousse T, Sakai LY, Rifkin DB. Specificity of latent TGF-beta binding protein (LTBP) incorporation into matrix: role of fibrillins and fibronectin. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227(12):3828–3836. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]