Abstract

Long-lived plasma cells (LLPCs) can persistently produce anti-factor VIII (FVIII) antibodies which disrupt therapeutic effect of FVIII in hemophilia A patients with inhibitors, The migration of plasma cells to BM where they become LLPCs is largely controlled by an interaction between the chemokine ligand CXCL12 and its receptor CXCR4. AMD3100 combined with G-CSF inhibit their interactions, thus facilitating the mobilization of CD34+ cells and blocking the homing of LLPCs. These reagents were combined with anti-CD20 to reduce B-cells and the specific IL-2/IL-2mAb (JES6-1) complexes to induce Treg expansion for targeting anti-FVIII immune responses. Groups of mice primed with FVIII plasmid and protein respectively were treated with the combined regimen for six weeks, and a significant reduction of anti-FVIII inhibitor titers was observed, associated with the dramatic decrease of circulating and bone marrow CXCR4+ plasma cells. The combination regimens are highly promising in modulating pre-existing anti-FVIII antibodies in FVIII primed subjects.

Keywords: Factor VIII; Hemophilia A; Inhibitors; Plasma cells, Immune tolerance; Immunomodulation; AMD3100; G-CSF

1. INTRODUCTION

Hemophilia A (HemA) is an inherited, X-linked, recessive disorder caused by deficiencies of functional plasma clotting factor VIII (FVIII)[1]. In clinical practice, the regular infusion of FVIII is currently the most effective strategy for treating severe HemA patients. Unfortunately, 25-30% of HemA patients develop inhibitory anti-FVIII antibodies (FVIII inhibitors), which significantly increase morbidity and lower the quality of life. Anti-FVIII antibodies neutralize the coagulant function of FVIII[2, 3] and represent the greatest limitation to successful FVIII replacement therapy[2, 4, 5]. As a result, strategies to treat FVIII inhibitor patients by eliminating inhibitory anti-FVIII Abs and inducing immune tolerance to FVIII have attracted much research interests[6-8].

Specific immunosuppressive reagents have been investigated previously for blocking the T cell-mediated immune responses by the induction or enhancement of Treg cell (Treg) activities, using a specific IL-2/IL-2mAb (JES6-1) complexes[9, 10] and/or rapamycin[11, 12]. In order to suppress the T effector cells and T memory cells functions, we and others also applied anti-CD3 as the therapeutic strategy[13, 14]. These strategies successfully prevented antibody production in HemA mice. However, it is much more challenging to down-modulate FVIII-specific immune responses in primed hemophilia subjects or animals with pre-existing inhibitory antibodies. It is believed that memory B and/or long-lived plasma cells (LLPCs) play a key role in maintaining established antibody responses. Importantly, FVIII-specific memory B cells are present in hemophilia patients with inhibitors whereas such cells are absent in healthy controls or patients without inhibitors[15]. FVIII-specific plasma cells (PCs) have also been identified in both spleen and bone marrow (BM) in HemA mice after FVIII infusions[16]. In our previous experiments, we found that B-cell depletion agents including anti-CD20 or combined therapies did not completely eliminate antibody production in HemA mice with pre-existing inhibitors (HemA inhibitor mice)[11, 17, 18]. CD20-targeted B cell depletion therapy in humans has been successful in the treatment of some antibody mediated autoimmune diseases and malignant B cell disorders[19, 20]. However, anti-CD20 does not directly target PCs since these cells express little, if any, CD20 and thus may be only partially effective in eradicating existing, long-lasting antibody responses. In the case of hemophilia with pre-existing inhibitory antibodies, long-lived humoral immunity may be manifested by the ability of long-lived spleen- and BM-PCs to survive for extended periods, independent of antigenic stimulation.

LLPCs survive in their niche and are refractory to immunosuppression, B cell depletion, and irradiation, thus providing persistent antibody production[21]. Elimination of LLPCs remains a therapeutic challenge. The migration of plasmablasts to the BM is a crucial differentiation step for the generation of LLPCs. Although a small proportion of LLPCs persists in the spleen, most LLPCs are maintained in the BM and provide humoral memory. PCs newly generated in the periphery enter the BM across the endothelium and migrate via CXC receptor 4 (CXCR4; the receptor for CXC type chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12)) to the CXCL12-abundant reticular (CAR) cells, a subpopulation of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs)[22-24]. CAR cells together with contribution from other hematopoietic components make up a protective PC survival niche. In this niche, PCs can survive for decades and maintain persistent antibody titers[25, 26]. If newly generated PCs cannot successfully enter this niche in a competitive process[27], or if long-lived PCs are dislocated from their niche[28], they undergo apoptosis. The development of novel therapeutic strategies that target the CXCL12/CXCR4 pathway to reduce LLPCs may represent a promising approach for treating patients with HemA inhibitors.

Based on this hypothesis, we aimed at identifying novel therapeutic strategies targeting LLPCs to eliminate or reduce inhibitor titers in HemA mice. AMD3100, an antagonist of CXCR4, was used to block the CXCL12/CXCR4 interaction, thus inhibiting the homing and retention of LLPCs. G-CSF (Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor) is a hematopoietic growth factor, which stimulates the mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells and enhances the activity of Tregs to promote the induction of T cell tolerance. In this study, we investigated the treatment protocols by each single agent, AMD3100 and G-CSF respectively, and combined treatment protocols using AMD3100, G-CSF, anti-CD20 and/or IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes targeting both T and B cell simultaneously in HemA inhibitor mice. Although the single agent regimens and two of the 3-agent combined regimens treated inhibitor mice showed transiently reduced inhibitor titers, the titers rose back up to high levels in a few weeks. However, in mice treated with 4-agent combination regimen, the inhibitor titers were significantly reduced or completely eliminated after three cycles of treatment and the low/no antibody titers were maintained over time.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Mice

All mice were maintained at a specific pathogen-free (SPF) facility according to the National Institutes of Health guidelines for animal care and the guidelines of Seattle Children's Research Institute. HemA mice in a 129/SV × C57BL/6 mixed genetic background were generated by targeted disruption of exon 16 of FVIII gene[29] and were used at the age of 6-8 wks.

2.2. Generation of HemA inhibitor mice

In order to generate HemA mice with pre-existing inhibitors, HemA mice were intravenously (i.v.) injected with 50 μg of FVIII plasmid (pBS-HCRHPI-FVIIIA[30]) in 2 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) via tail vein in 8-10 seconds, or intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected with low dose FVIII protein (2U/mouse/wk; Kogenate®, Bayer (Whippany, NJ)) consecutively for 4 weeks. 4-6 weeks after the hydrodynamic or intraperitoneal injection, plasma samples were collected for examining the inhibitor titers by Bethesda assay[31]. Previously we have characterized the T and B cell responses from mice treated with FVIII protein using i.v. and i.p. injection routes and found that the responses are the same within the two groups. Thus we adopted i.p. injection method for the experiments.

2.3. Immunomodulation by injection of IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes to induce in vivo expansion of Treg cells

IL-2/anti-IL-2mAb (JES6-1A12) complexes were prepared as described[32]. 1 μg recombinant mouse IL-2 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) was mixed with 5 μg anti-IL-2mAb (JES6-1A12) (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), incubated at 37° C for 30 mins, and then injected i.p. into mice according to schedules specified in Results. Blood samples were taken from the retro-orbital plexus at serial time points and assessed for FVIII activities and anti-FVIII antibody levels.

2.4. B cells depletion by anti-CD20, AMD3100 and G-CSF treatment

Anti-CD20 IgG2a antibody (clone 18B12, kindly provided by Biogen Idec), AMD3100 (R & D system, USA) and recombinant murine G-CSF (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) were administered two weeks per cycle for 3 cycles to deplete B cells in inhibitor mice. Anti-CD20 was given at 250 μg/mouse three i.v. doses 14 days apart; AMD3100 (plerixafor; Mozobil®), at 200 μg/d/mouse in sterile 200 μl of PBS were injected i.p. consecutively for 10-days; G-CSF was administered by daily i.p. injection at a dose of 250 μg/kg/d for 6 days. To assess B cell depletion, peripheral blood was collected at different time points and lymphocytes were isolated for staining and flow cytometry analysis.

2.5. Flow cytometry and antibodies

Cell suspensions of peripheral blood and spleens of each treated mouse group were prepared according to standard protocols. Cell suspensions were stained for FACS analysis using the following antibodies [obtained from eBioscience unless otherwise stated]: PE-Cy5-anti-mouse CD25; FITC-anti-mouse CD62L (L-selectin); Alexa Fluor® 647-anti-mouse/rat Foxp3; PE-anti-mouse CD152 (CTLA-4); Alexa Flour®700-anti-mouse CD4 (BD Pharmingen™; San Jose, CA); PE-Cy7-anti-mouse GITR (BD Pharmingen™); FITC anti-mouse/human Helios (BioLegend; San Diego, CA); Alexa Fluor®700-anti-mouse B220; FITC-anti-mouse IgD; PE-Cy7-anti-mouse IgM and PE-anti-mouse CD138. Cells were first stained for T cell surface markers CD4, CD25, CD62L, and GITR, and subsequently stained with intracellular Treg markers Foxp3 and CTLA-4 following the company protocol (eBioscience). For B cell populations, cells were stained with surface markers B220, IgD, IgM and CD138. Samples were analyzed on an LSRII flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Palo Alto, CA) and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

2.6. FVIII activities and inhibitor titers assays

Peripheral blood samples were taken from the experimental mice and collected in a 3.8% sodium citrate solution. FVIII activities were evaluated from the activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) by a modified clotting assay using FVIII deficient plasma and reagents[30, 33]. FVIII activities were calculated from a standard curve generated with serially diluted normal human pooled plasma. Anti-FVIII antibody titers were measured by Bethesda assay as previously described [17].

2.7. Quantitation of anti-FVIII IgG1 levels

Plasma samples were prepared from peripheral blood of mice treated with IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes + anti-CD20 + AMD3100 + G-CSF, Anti-CD20 + AMD3100 + G-CSF, hFVIII plasmid only, or untreated naive mice. Anti-FVIII-IgG1 concentrations in plasma were evaluated using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) [34], and the data were interpolated against the linear range on the standard curves.

2.8. The enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay

A FVIII specific antibody-secreting cells (ASCs) ELISPOT assay was performed as described previously[16, 35]. The CD138+ plasma cells isolated from the spleen and bone marrow (CD138 isolation kit, Mitenyi Biotec. Auburn, CA) were plated at 1×10^6 cells/well first into the capture antibody-coated assay plate in a final volume of 100 μl per well. Plates were gently tapped on each side to ensure even distribution of the cells as they were settled and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator. Following completion of the ELISPOT protocol, the plates were air dried in a laminar flow hood prior to analysis. ELISPOT plates were scanned and analyzed using an ImmunoSpot®5.0 UV Reader (Cellular Technology Ltd, Shakwe Heights, OH). Spots were counted automatically by using ImmunoSpot®5.0 software for each well. For FVIII specific-memory B cells ELISPOT assay, 5×10^5 cells (200 μl/well) of the CD138− fraction were cultured and stimulated with FVIII (2U/well) in a 96-well round bottom plate. Cultures were kept at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 6-days. The newly formed ASCs were detected and analyzed using the ImmunoSopt®5.0 UV Reader..

2.9. Statistical analysis

Results are presented as means±SD. The statistical significance of the difference between means was determined using the two-tailed Student's t test. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Complete elimination of inhibitor titers in FVIII plasmid-primed HemA inhibitor mice following combined treatment with IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes, Anti-CD20, AMD3100 and G-CSF

We have shown previously that treatment with IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes to expand Tregs in vivo has successfully prevented anti-FVIII antibodies formation in HemA mice following FVIII plasmid-mediated gene therapy[11]. In addition, administration of anti-murine CD20 depleted 98% of B cells and reduced ~30% of inhibitor titers in the HemA inhibitor mice[17]. However, inhibitor titers were not completely eliminated by either IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes or anti-CD20 alone in the inhibitor mice (data not shown). Therefore, we investigated strategies aiming at reducing/eradicating LLPCs in this study to reduce pre-existing inhibitor titers. We first used AMD3100 only treatment for contiguous 10-days in FVIII-plasmid primed inhibitor mice. It was found that both inhibitor titers and PCs were initially reduced compared to the inhibitor only control mice (Supplemental Fig. 1); however, the titers returned to higher levels afterwards. Moreover, G-CSF only treatment in the FVIII-plasmid primed inhibitor mice showed transiently reduced inhibitor titers (Supplemental Fig. 2A), total B cells (%; Supplemental Fig. 2C) and CXCR4+ PCs (LLPCs, numbers; Supplemental Fig. 2D) compared to the inhibitor only control (Supplemental Fig. 2B). In order to improve the immune modulation effects, we then investigated IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes/Rapamycin plus AMD3100 treatment in the inhibitor mice for 4-weeks (Supplemental Fig. 3). Rapamycin was reported to sustain Treg cells activities. IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes/Rapamycin induced more than 5-fold Treg expansion (Supplemental Fig. 4) which is similar to the expansion achieved by the IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes only treatment. The inhibitor titers were significantly decreased during the treatment period specifically 2 weeks post treatment, indicating that homing of LLPCs was effectively blocked by using AMD3100 due to the reduction of CXCR4+ PCs (%) (Supplemental Fig. 5D). However, the titers increased afterwards (Supplemental Fig. 3A) compared to the inhibitor only control mice which showed persistently high inhibitor titers (Supplemental Fig. 3B).

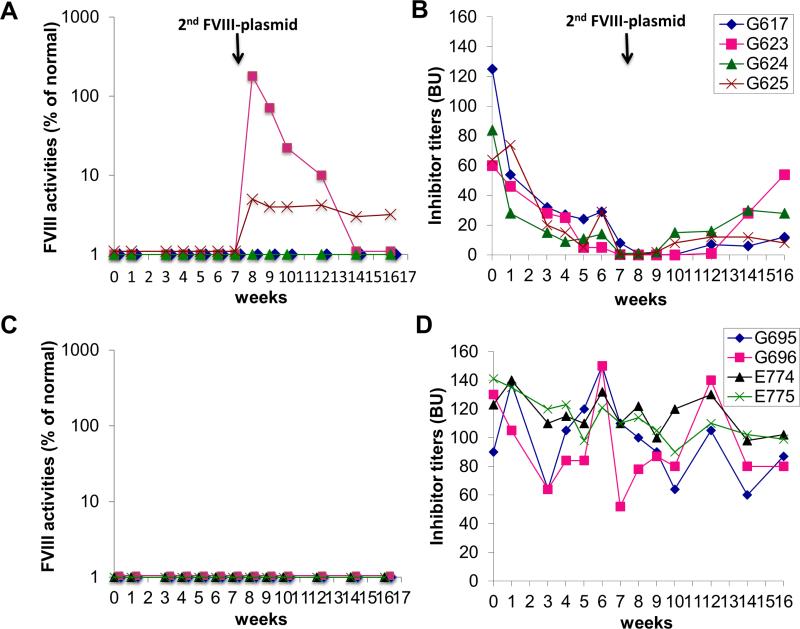

Thus, in order to more effectively reduce pre-existing anti-FVIII antibodies, we evaluated the combination strategy by targeting both functional PCs and LLPCs simultaneously. FVIII plasmid primed HemA inhibitor mice (n=4/group) were treated with the combination of IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes + anti-CD20 + AMD3100 + G-CSF one cycle per two weeks (Supplemental Fig. 6) for three cycles. FVIII plasmid-primed HemA inhibitor only mice which did not receive any further treatment were served as the control group (n=4/group). After 6 weeks of combined treatments, inhibitor titers were almost completely eliminated in all treated mice after the combined treatment (Fig. 1B) compared to the inhibitor only control mouse group (Fig. 1D) of which the inhibitor titers remained at high levels. After challenged 2nd time with FVIII plasmid, two mice had recovered its FVIII activity after treatment (Fig. 1A, G623 and G625). In contrast, the control FVIII-plasmid primed inhibitor mice did not show any FVIII activities at all times (Fig. 1C). Although most of the treated mice eventually lost their FVIII activities, the inhibitor titers remained at persistently lower levels compared to their initial titers. This set of experiments was repeated without second plasmid challenge, the inhibitor titers were significantly reduced or eliminated and remained at low levels over time (Supplemental figure 7). In addition, a separate group with the same combination treatment plus rapamycin yielded similar results. These results indicate that partial tolerance to FVIII was induced by the combined immunomodulation protocol in a gene therapy setting.

Figure 1. FVIII activities and inhibitor titers following treatment with combination regimen in FVIII-plasmid primed HemA inhibitor mice.

HemA mice were initially primed with FVIII-plasmids for induction of inhibitor titers. (A, B) One group of inhibitor mice (n=4) were treated with the combination regimen IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes + anti-CD20 + G-CSF + AMD3100; (C, D) the inhibitor mice (n= 4) were setup as the non-treated inhibitor only control group. Combined treatment was scheduled at 2-weeks per cycle for three cycles. Peripheral blood was then collected on weeks 1, 3, 6 and 10 for evaluation of FVIII activities (A, C) and inhibitor titers (B, D) at different time points. 2nd FVIII-plasmid challenge was scheduled on week 8 when the inhibitor titers were decreased to zero in mice after 3-cycles of combination regimen. Data shown is representative of two independent experiments.

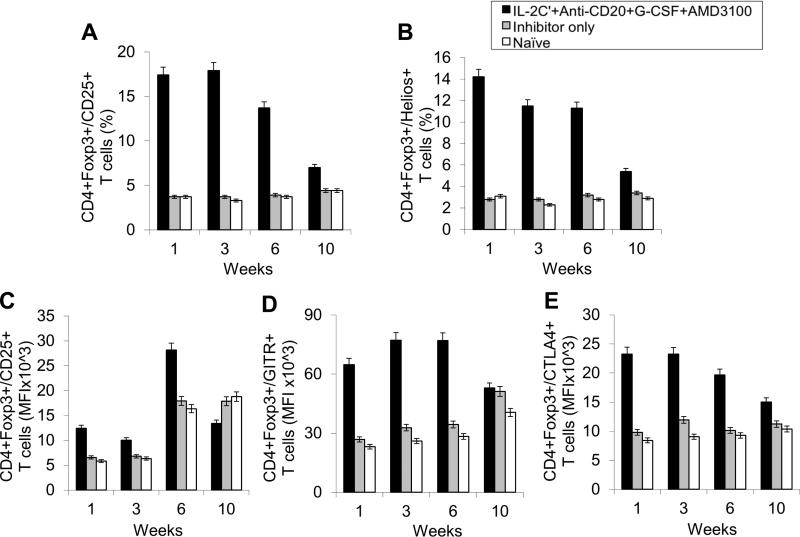

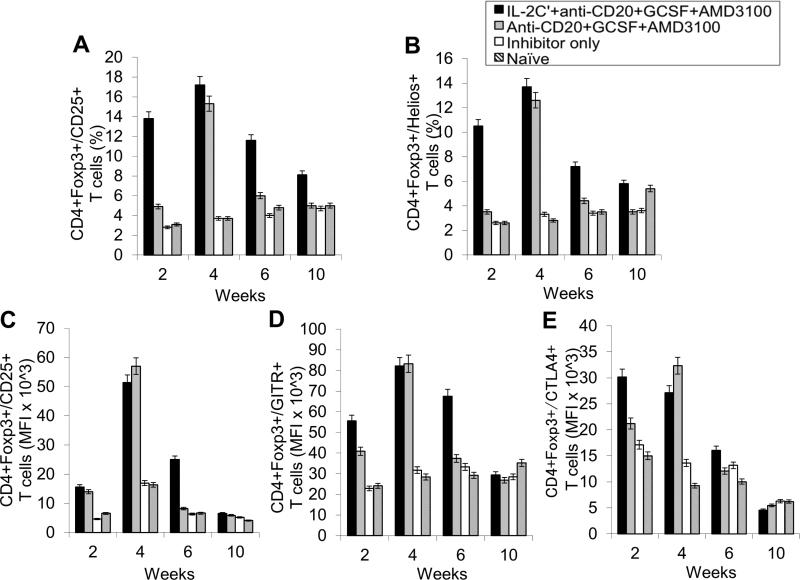

Next, we evaluated changes in T- and B-cell populations in different mouse groups. As expected, the percentages of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells (Fig. 2A and Supplemental Fig. 8A) and CD4+CD25+Helios+ T cells (Fig. 2B and Supplemental Fig. 8A) within the CD4+ T cell compartment were significantly increased in treated group during treatment period due to the use of IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes. The expanded Tregs declined rapidly to baseline levels within 2 weeks post treatment. Similarly to our previous studies[11], IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes-expanded Tregs showed considerably higher expression of molecules crucial for the suppressive function of Tregs, including CD25 (Fig. 2C), glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor (GITR) (Fig.2D), and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) (Fig. 2E) during the treatment period.

Figure 2. Effects of immunomodulation on CD4+ T cells, CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs cells and T cell activation markers in peripheral blood of combination regimen treated FVIII-plasmid primed inhibitor mice on weeks 1, 3, 6 and 10.

Lymphocytes were isolated from peripheral blood of IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes + anti-CD20 + G-CSF + AMD3100 treated inhibitor mice (black bar; n=4), inhibitor only mice (gray bar; n=4) and naive mice (white bar; n=4) at different time points. (A) CD4+Foxp3+/CD25+ Tregs in CD4+ T cells and (B) CD4+Foxp3+/Helios+ cells in CD4+ T cells were stained and analyzed by flow cytometry during treatment. Blood cells were also stained and analyzed for Treg activation markers: (C) CD25, (D) GITR and (E) CTLA4. Data shown are median fluorescence intensity (MFI) values of the three activation markers, and representative of two independent experiments.

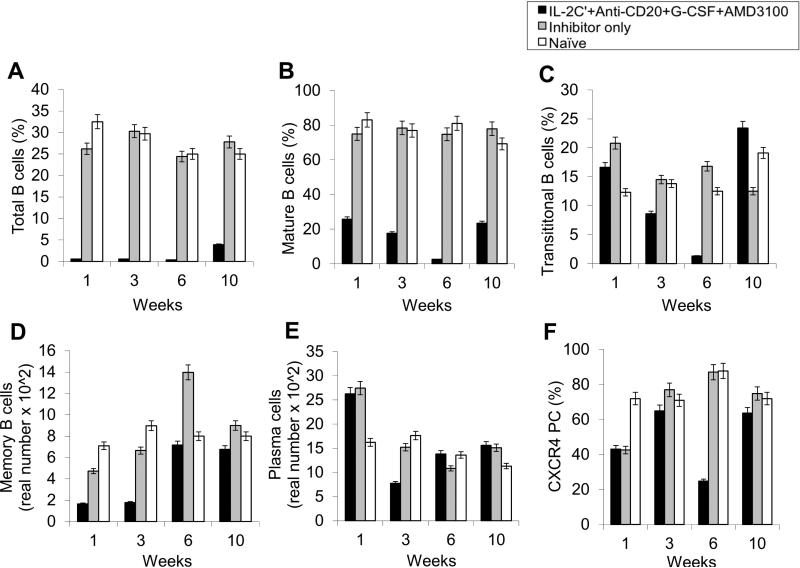

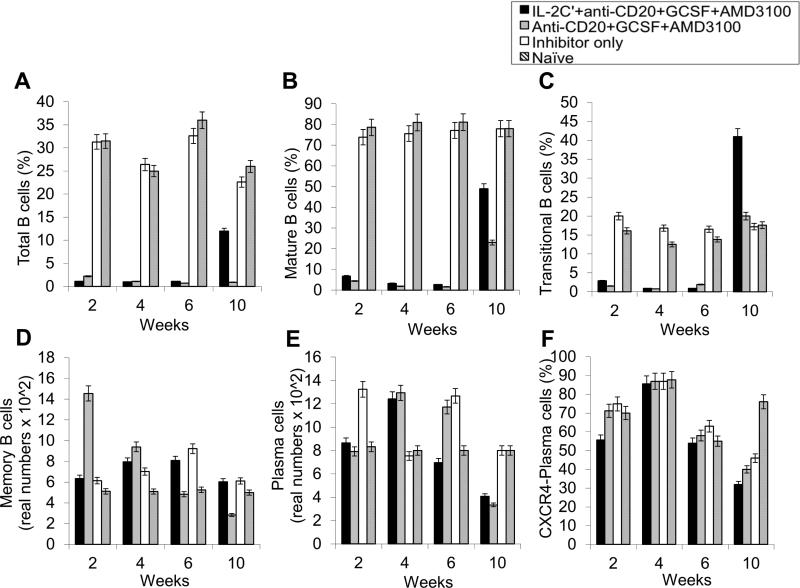

The important Effects of anti-CD20, AMD3100 as well as G-CSF on various B-cell populations including especially LLPCs were evaluated in the HemA inhibitor mice. After three cycles of combined treatments, we observed significant decreases in total B-cells (B220+ cells) (%) (Fig. 3A and Supplemental Fig. 8B); mature B-cells (IgD+IgMlow) (%) (Fig. 3B and Supplemental Fig. 8B); transitional B-cells (IgM+IgDlow) (%) (Fig. 3C and Supplemental Fig. 8B); memory B-cells (IgM−IgD−) (real numbers) (Fig. 3D and Supplemental Fig. 8B); plasma cell (B220−CD138+) (real numbers) and CXCR4+ plasma cells (B220−CD138+CXCR4+) (%) (Fig. 3E, F and Supplemental Fig. 8B) on week 3 and week 6 respectively in the treated mice compared to the control inhibitor mice and naive mice. There are increases in the granularity of CD4− cells probably due to cell activation by drug treatment and the increases promptly returned to normal levels after treatment.

Figure 3. Effects of immunomodulation on total B, mature B, transitional B, memory B, plasma, and CXCR4+ plasma cells in peripheral blood of each mouse group.

Lymphocytes were isolated from the peripheral blood of IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes + anti-CD20 + G-CSF + AMD3100 combination treated inhibitor mice (black bar; n=4), inhibitor only mice (gray bar; n=4) and naive mice (white bar; n=4) at different time points during the treatment period (week 1, 3, 6 and 10). (A) B220+ (total) B cell, (B) IgM+IgDhi (mature) B cells, (C) IgMhiIgD+ (transitional) B cells, (D) IgM−IgD− (memory) B cell, (E) B220−CD138+ PCs as well as (F) CXCR4+ specific PCs populations were investigated using flow cytometry analysis. Data shown are cell percentages (A-C, and F) and real numbers (D and E), and representative of two independent experiments.

3.2. Combination treatments similarly reduced inhibitor titers and LLPCs in FVIII protein-primed HemA inhibitor mice

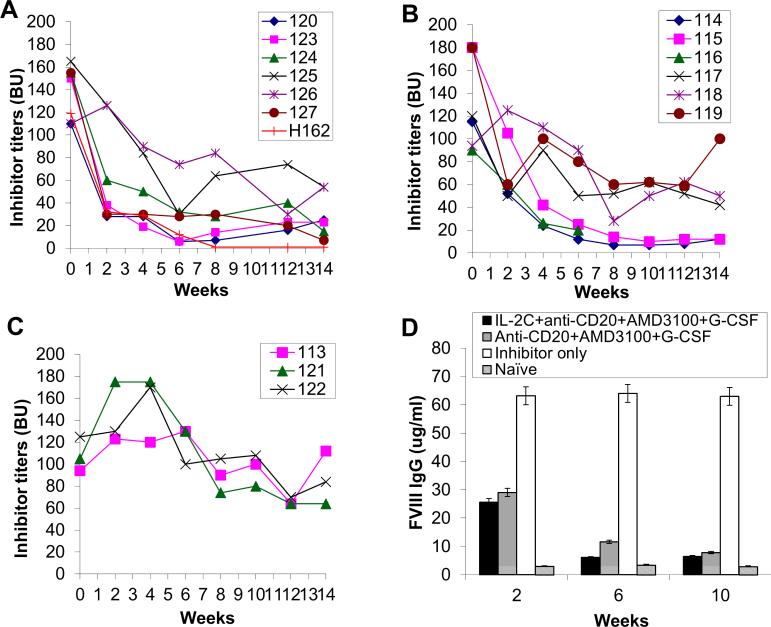

With the encouraging results obtained from FVIII plasmid-primed HemA inhibitor mice, we next studied if similar combination treatment can eliminate/reduce inhibitor titers in FVIII protein-primed HemA inhibitor mice. Two groups of FVIII-protein primed HemA inhibitor mice were treated with different combination therapy two weeks per cycle for three cycles: (1) IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes + anti-CD20 + AMD3100 + G-CSF (n=7/group), (2) anti-CD20 + AMD3100 + G-CSF (n=6/group). The FVIII protein-primed HemA inhibitor mice (n=3) which did not receive any further treatments were served as the control group. After 6 weeks treatment, the inhibitor titers were significantly reduced/eliminated in 5 out of 7 IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes + anti-CD20 + AMD3100 + G-CSF treated mice (Fig. 4A) compared to the control inhibitor mouse group (Fig. 4C). In addition, 3 out of 6 anti-CD20 + AMD3100 + G-CSF (Fig. 4B) combined treatment group (Fig. 4B) showed significant reduction of their inhibitor titers following treatment. In accordance with these results, high levels of anti-FVIII IgG1 examined by ELISA persisted in the plasma of FVIII protein-primed inhibitor mice over time (Fig. 4D; white bar), whereas anti-FVIII IgG1 levels were significantly reduced on weeks 2, 6 and 10 in the plasma of both the IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes + anti-CD20 + AMD3100 + G-CSF treated group (Fig. 4D; black bar) and the anti-CD20 + AMD3100 + G-CSF treated group (Fig. 4D; gray bar). Additionally, two more separated FVIII protein-primed HemA inhibitor mouse group were set-up using the same combination treatment strategy, and similar results were obtained (Supplemental figure 9).

Figure 4. Inhibitor titers and anti-FVIII IgG1 levels in FVIII protein primed HemA mice with pre-existing inhibitors following combination treatment.

Two groups of HemA mice were treated separately with different combination regimens 2-weeks per cycle for 3 cycles: (A) IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes + anti-CD20 + AMD3100 + G-CSF (n=7), (B) Anti-CD20 + AMD3100 + G-CSF (n=6), and (C) Inhibitor mice only (n=3) as the control group. Peripheral blood was collected at different time points following the combination treatment. Anti-FVIII antibody titers were assessed by Bethesda assay over time. Each symbol represents data obtained from an individual mouse. (D) Anti-FVIII IgG1 levels were examined in each treated mouse group by ELISA. Data shown is representative of two independent experiments.

The changes in T- and B-cell populations were investigated for the FVIII protein-primed HemA inhibitor mice treated using the combination therapy. Peripheral blood of mice treated with IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes + anti-CD20 + AMD3100 + G-CSF (n=6; Fig. 5, black bar), mice treated with anti-CD20 + AMD3100 + G-CSF (n=6; Fig. 5, gray bar), inhibitor only mice (n=3; Fig. 5, white bar) and naive mice (n=3; Fig. 5, slant bar) were collected at weeks 2, 4, 6 and 10 and subjected to flow cytometry analysis (Supplemental Fig. 7). Fig 5A showed that the percentage of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells (Fig. 5A) and CD4+CD25+Helios+ T cells (Fig. 5B) within the CD4+ T cell compartment were significantly increased in IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes treated mice compared to the other groups during 6-weeks treatment period. Tregs also showed expansion in the anti-CD20+AMD3100+G-CSF treated group (Fig. 5A). This is not surprising since G-CSF has been reported to induce CD4+CD25+ Treg cells in blood and spleen. The induction maximum in our experiment is at 4 weeks (Fig. 5), consistent with other reports [36]. The expanded Treg cells from both treated groups showed considerably higher expression of molecules (shown by MFI levels) crucial for the suppressive function of Treg cells, including CD25 (Fig. 5C), GITR (Fig. 5D), and CTLA-4 (Fig. 5E).

Figure 5. Effects of immunomodulation of CD4+ T cells, CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ s and T cell activation markers in peripheral blood of treated HemA inhibitor mice on weeks 2, 4, 6 and 10.

Lymphocytes were isolated from the peripheral blood of mice treated with combination regimens IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes + anti-CD20 + AMD3100 + G-CSF (n=7, black bar) and Anti-CD20 + AMD3100 + G-CSF (n=6, gray bar), and inhibitor only mice (n=3, white bar). Peripheral blood were collected at different time points following the combination treatment.(A) CD4+Foxp3+/CD25+ cells (%) in CD4+ T cells and(B) CD4+Foxp3+/Helios+ cells (%) in CD4+ T cells were stained and analyzed by flow cytometry during treatment. Blood cells were also stained and analyzed for Treg markers: (C) CD25, (D) GITR and (E) CTLA4. Data shown are MFI values of the three activation markers, and representative of two independent experiments.

Effects of anti-CD20, AMD3100 as well as G-CSF were evaluated on B-cell populations especially the PCs and CXCR4+ LLPCs in the hemophilia A inhibitor mice treated with different combination therapies. After three cycles of combined treatments, proportions of B-cell populations were measured by flow cytometry. We observed significant reduction in total B-cells (B220+ cells) (%) (Fig. 6A); mature B-cells (IgD+IgMlow) (%) (Fig. 6B); transitional B-cells (IgM+IgDlow) (%) (Fig. 6C); memory B-cells (IgM−IgD−) (real numbers) (Fig. 6D); PCs (B220−CD138+) (real numbers) (Fig. 6E) and CXCR4+ LLPCs (B220−CD138+CXCR4+) (%) (Fig. 6F) in both inhibitor mouse groups treated with combination therapies compared to the inhibitor only and naive untreated mouse groups.

Figure 6. Effects of immunomodulation on total B, mature B, transitional B, memory B, plasma B and CXCR4+ plasma B cells in peripheral blood of treated HemA inhibitor mice.

Lymphocytes were isolated from the peripheral blood of naive (slant bar; n=3), inhibitor only (white bar; n=3), anti-CD20 + G-CSF + AMD3100 (gray bar; n=6) and IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes + anti-CD20 + G-CSF + AMD3100 (black bar, n=7) treated mice. (A) B220+ (Total) B cells, (B) IgM+IgDhi (mature) B cells, (C) IgMhiIgD+ (transitional) B cell, (D)IgM−IgD− (memory) B cells, (E) B220−CD138+ PCs and (F) CXCR4+ PCs were stained and analyzed by flow cytometry during treatment period (week 2, 4, 6 and 10). Data shown are cell percentages (A-C, and F) and real numbers (D and E), and representative of two independent experiments.

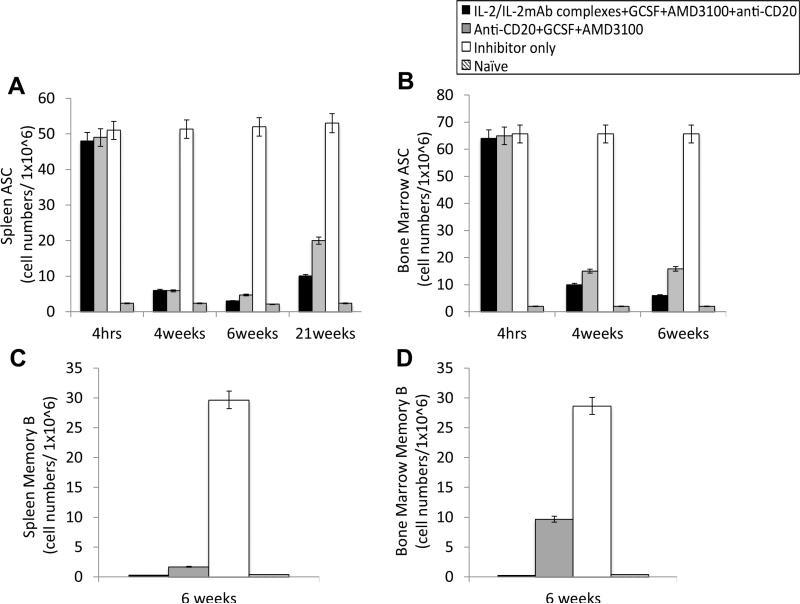

3.3. Antibody-secreting cells (ASCs) and FVIII-specific memory B cells were depleted using the combined treatment strategy targeting LLPCs

We next investigated ASCs and FVIII-specific memory B cells at 4hrs, 4-weeks, 6-weeks and 21-weeks following the first treatment of combination therapies in the FVIII-protein primed inhibitor mice. As shown in Fig 7, ASCs isolated from the spleens (Fig. 7A and C) and BM (Fig. 7B and D) of both mouse groups treated with IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes + G-CSF + AMD3100 + anti-CD20 (black bar) and anti-CD20 + G-CSF + AMD3100 (gray bar) were significantly reduced on weeks 4 compared to the inhibitor only (white bar) and naive mice (slant bar) by the ELISPOT assay, indicating that the combination therapies are effective to reduce the numbers of LLPCs, leading to the reduction of anti-FVIII antibodies in HemA inhibitors. In addition, the two combination therapy treated groups showed significant depletion of their FVIII-specific memory B cells in the spleens (Fig. 7C) and BM (Fig. 7D) on week 6 following combination therapy. Similar results were obtained from FVIII-plasmid primed inhibitor mice (data not shown).

Figure 7. Depletion of FVIII-specific antibody-secreting cells (ASCs) and memory B cells in the inhibitor mice treated with two different combination regimens.

FVIII protein-primed inhibitor mice were treated with IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes + G-CSF + AMD3100 + anti-CD20 (black bar, n=2), Anti-CD20 + G-CSF + AMD3100 (gray bar, n=2), inhibitor only control (white bar, n=2), and naïve mice control (slant bar, n=2). Cells were isolated by MACS from spleens (A, C) and BMs (B, D) at 4hrs, 4weeks, 6weeks and 21 weeks following the first combination treatment. 1×106 cells were used to detect FVIII-specific ASC (A, B) and FVIII-specific memory B cells (C, D) by ELISPOT assays. The two mouse groups treated with combination regimens showed dramatically depletion of their ASCs at 4 and 6 weeks both in spleen and BM compare to the inhibitor only control. FVIII-specific memory B cells were significantly depleted on weeks 6 following combination treatment. Data shown are the average spot numbers of ELISPOT results.

4. DISCUSSION

It is highly challenging to treat HemA patients with pre-existing inhibitors. Likewise, it has been difficult to modulate pre-existing anti-FVIII neutralizing antibodies in FVIII-plasmid or FVIII protein-primed HemA mice. Pre-established anti-FVIII antibodies can circulate for long periods of time and is mostly attributed to the persistence of memory B cells and LLPCs. Without first reducing the inhibitor titers, even if new antibody formation can be blocked by novel strategies, administration of FVIII or gene therapy will not help correct FVIII deficiency due to pre-existing inhibitory antibodies. Therefore, it is paramount to treat patients with high-titer inhibitory antibodies with effective strategies to reduce and best eliminate pre-existing inhibitory antibodies before attempting tolerance induction. Blockade of co-stimulatory pathway has been shown to prevent FVIII-specific murine memory B cells from becoming re-stimulated by FVIII in vitro and in vivo[37]. In our previous experiments, we have demonstrated that the combination treatment of IL-2/IL-2mAb complexes + rapamycin + anti-CD20 + FVIII reduced FVIII-specific memory B cells and ASCs from the spleen, leading to transient decreases of pre-existing neutralizing antibody titers [17]. However, the inhibitor titers rose back to higher levels. Monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody depletes short-lived plasmablasts, whereas LLPCs survive and continue to produce antibodies. Thus, strategies for targeting LLPCs may be important for treating pre-existing antibodies and provide potent new treatment modalities.

LLPCs reside in multiple lymphoid organs and can migrate to non-lymphoid organs in diseased states. BM houses the majority of PCs in healthy individuals [38, 39]. The process of cells homing to and retention in the BM remains poorly understood. However, it is widely accepted that a niche in the BM is required for not only recruitment but also survival of LLPCs for years. CXCL12 and its receptor CXCR4 are assumed to play important roles for the recruitment of ASCs to the BM and their retention/maturation at the site [40] to become antigen-specific LLPCs, which in our case, persistently generate anti-FVIII inhibitory antibodies. Several factors have been proposed to mediate PC survival in the BM, including IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and APRIL [41, 42]. It is suggested that APRIL and its receptor, B cell mature antigen (BCMA), are the most important components of the niche in the survival of all ASCs [43, 44]. Migration and homing of plasmablasts to BM is a complex process, which involves many factors in the microenvironment. In transgenic mice reconstituted with CXCR4-deficient fetal liver cells, PCs fail to accumulate in the BM in normal numbers [45, 46]. Nevertheless, CXCR4 expression is not an absolute prerequisite for homing, and other chemokines may be involved in the entry pathway into the BM. Thus, further understanding of PC differentiation is important, particularly as it relates to the selection of high-affinity clones into the LLPC pool.

In order to specifically target LLPCs and prevent new antibody production, we explored drugs that target migration or retention of PCs. The migration of plasmablasts to their survival niche in BM or spleen is a crucial differentiation step for the generation and maintenance of LLPCs. AMD3100, a CXCR4 chemokine receptor antagonist, is a novel stem-cell mobilizing agent originally identified as an anti-HIV agent. The interaction of CXCR4 receptor with its ligand CXCL12 is important of retaining CD34+ cells in BM; blocking this interaction leads to the mobilization of stem cells into the peripheral blood [47]. Liles et al.[48, 49] first recognized the potential clinical application of AMD3100 for CD34+ cell mobilization in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. G-CSF, the prototypical mobilizing cytokine, also induces hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell mobilization from the BM to circulation[50]. This process is mediated through suppression of osteoblasts and disruption of CXCR4/CXCL12 signaling. Currently, GCSF is the most widely used agent to induce PC mobilization due to its potency, predictability, and safety[51]. The mechanism mediating the G-CSF induced decrease of CXCL12 protein expression in the BM has not been defined. However, AMD3100 in combination with G-CSF resulted in ~17-fold more efficient mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells than AMD3100 or G-CSF alone [52].

As shown in our ELISPOT data (Fig. 7), the combination treatment including AMD3100 and G-CSF significantly reduced the numbers of FVIII-specific ASC cells in the treated mice. In addition, FVIII-specific memory B cells were eliminated by anti-CD20 treatment in the combination strategy. Lastly, we used IL2/anti-IL2mAb complexes to induce in vivo expansion of Tregs to promote tolerance induction. By using the combination of these agents, we achieved significant reduction/elimination of inhibitor titers shown in Figs. 1 and 4. We also found that G-SCF can induce significant expansion of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+Treg cells. It will be interesting to compare the efficacy of reducing inhibitor titers by replacing IL2/anti-IL2mAb complexes with additional G-CSF treatment. Furthermore, following elimination of anti-FVIII inhibitors, part of the treated mice challenged 2nd time with FVIII-plasmid generated increased FVIII activity, indicating that FVIII can exert its functional role after reduction/elimination of the preexisting inhibitors. Taken these results together, our results indicated that blocking the migration pathway of PCs can efficiently decrease the numbers of LLPCs in the spleen and BM, leading to significant reduction of pre-existing inhibitory antibody titers and facilitating the recovery of FVIII function.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

AMD3100 combined with G-CSF effectively reduced FVIII-specific PCs, resulting in decreases of pre-exisitng inhibitor titers in hemophilia mice.

Reduction of LLPCs and associated persistent inhibitors was paramount for the recovery of FVIII activity to ensure the success of immune tolerance induction to FVIII.

Transient combination regimens targeting both T and B cells significantly reduced anti-FVIII inhibitor titers and maintained low inhibitor titers over time.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a R01 grant (R01 HL69049) from NIH-NHLBI and by a special project grant from Bayer Hemophilia Foundation to CHM. We also thank Bayer (Whippany, NJ) for providing recombinant FVIII (Kogenate®) and Dr. Chérie Butt at Biogen Idec (Weston, MA) for providing anti-mouse CD20 for our experiments.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Addendum

CLL and CHM designed the experiments, CLL, MJL, SCS performed the experiments. CLL and CHM wrote the paper.

Competing Interest Statement

None of the authors has competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antonarakis SE, Youssoufian H, Kazazian HH., Jr. Molecular genetics of hemophilia A in man (factor VIII deficiency). Mol Biol Med. 1987;4:81–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darby SC, Keeling DM, Spooner RJ, Wan Kan S, Giangrande PL, Collins PW, Hill FG, Hay CR, Organisation UKHCD The incidence of factor VIII and factor IX inhibitors in the hemophilia population of the UK and their effect on subsequent mortality, 1977-99. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:1047–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2004.00710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lacroix-Desmazes S, Navarrete AM, Andre S, Bayry J, Kaveri SV, Dasgupta S. Dynamics of factor VIII interactions determine its immunologic fate in hemophilia A. Blood. 2008;112:240–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-124941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehrenforth S, Kreuz W, Scharrer I, Linde R, Funk M, Gungor T, Krackhardt B, Kornhuber B. Incidence of development of factor VIII and factor IX inhibitors in haemophiliacs. Lancet. 1992;339:594–8. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90874-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lusher JM, Arkin S, Abildgaard CF, Schwartz RS. Recombinant factor VIII for the treatment of previously untreated patients with hemophilia A. Safety, efficacy, and development of inhibitors. Kogenate Previously Untreated Patient Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:453–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302183280701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott DW, Pratt KP, Miao CH. Progress toward inducing immunologic tolerance to factor VIII. Blood. 2013;121:4449–56. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-478669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sack BK, Merchant S, Markusic DM, Nathwani AC, Davidoff AM, Byrne BJ, Herzog RW. Transient B cell depletion or improved transgene expression by codon optimization promote tolerance to factor VIII in gene therapy. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lillicrap D, Fijnvandraat K, Santagostino E. Inhibitors - genetic and environmental factors. Haemophilia. 2014;20(Suppl 4):87–93. doi: 10.1111/hae.12412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu CL, Ye P, Lin J, Djukovic D, Miao CH. Long-term tolerance to factor VIII is achieved by administration of interleukin-2/interleukin-2 monoclonal antibody complexes and low dosages of factor VIII. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:921–31. doi: 10.1111/jth.12576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu CL, Ye P, Yen BC, Miao CH. In vivo expansion of regulatory T cells with IL-2/IL-2 mAb complexes prevents anti-factor VIII immune responses in hemophilia A mice treated with factor VIII plasmid-mediated gene therapy. Mol Ther. 2011;19:1511–20. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu CL, Ye P, Lin J, Miao CH. Development of novel strategies to modulate preexisting anti-factor VIII immune responses in hemophilia A inhibitor mice treated with factor VIII plasmid-mediated gene therapy.. American Society of Gene and Cell Therapy 14th Annual Meeting; Seattle, WA. May18-24, 2011Abs.p. 294. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moghimi B, Sack BK, Nayak S, Markusic DM, Mah CS, Herzog RW. Induction of tolerance to factor VIII by transient co-administration with rapamycin. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:1524–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04351.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng B, Ye P, Rawlings DJ, Ochs HD, Miao CH. Anti-CD3 antibodies modulate anti-factor VIII immune responses in hemophilia A mice after factor VIII plasmid-mediated gene therapy. Blood. 2009;114:4373–82. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-217315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waters B, Qadura M, Burnett E, Chegeni R, Labelle A, Thompson P, Hough C, Lillicrap D. Anti-CD3 prevents factor VIII inhibitor development in hemophilia A mice by a regulatory CD4+CD25+-dependent mechanism and by shifting cytokine production to favor a Th1 response. Blood. 2009;113:193–203. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-151597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Helden PM, Kaijen PH, Fijnvandraat K, van den Berg HM, Voorberg J. Factor VIII-specific memory B cells in patients with hemophilia A. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:2306–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hausl C, Maier E, Schwarz HP, Ahmad RU, Turecek PL, Dorner F, Reipert BM. Long-term persistence of anti-factor VIII antibody-secreting cells in hemophilic mice after treatment with human factor VIII. Thromb Haemost. 2002;87:840–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu CL, Ye P, Lin J, Butts CL, Miao CH. Anti-CD20 as the B-Cell Targeting Agent in a Combined Therapy to Modulate Anti-Factor VIII Immune Responses in Hemophilia a Inhibitor Mice. Front Immunol. 2014;4:502. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nozaki Y, Mitumori T, Yamamoto T, Kawashima I, Shobu Y, Hamanaka S, Nakajima K, Komatsu N, Kirito K. Rituximab activates Syk and AKT in CD20-positive B cell lymphoma cells dependent on cell membrane cholesterol levels. Exp Hematol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beckwith KA, Frissora FW, Stefanovski MR, Towns WH, Cheney C, Mo X, Deckert J, Croce CM, Flynn JM, Andritsos LA, Jones JA, Maddocks KJ, Lozanski G, Byrd JC, Muthusamy N. The CD37-targeted antibody-drug conjugate IMGN529 is highly active against human CLL and in a novel CD37 transgenic murine leukemia model. Leukemia. 2014;28:1501–10. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tedder TF. CD19: a promising B cell target for rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2009;5:572–7. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winter O, Dame C, Jundt F, Hiepe F. Pathogenic long-lived plasma cells and their survival niches in autoimmunity, malignancy, and allergy. J Immunol. 2012;189:5105–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma Q, Jones D, Springer TA. The chemokine receptor CXCR4 is required for the retention of B lineage and granulocytic precursors within the bone marrow microenvironment. Immunity. 1999;10:463–71. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suratt BT, Petty JM, Young SK, Malcolm KC, Lieber JG, Nick JA, Gonzalo JA, Henson PM, Worthen GS. Role of the CXCR4/SDF-1 chemokine axis in circulating neutrophil homeostasis. Blood. 2004;104:565–71. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zou YR, Kottmann AH, Kuroda M, Taniuchi I, Littman DR. Function of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in haematopoiesis and in cerebellar development. Nature. 1998;393:595–9. doi: 10.1038/31269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radbruch A, Muehlinghaus G, Luger EO, Inamine A, Smith KG, Dorner T, Hiepe F. Competence and competition: the challenge of becoming a long-lived plasma cell. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:741–50. doi: 10.1038/nri1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ratajczak MZ, Serwin K, Schneider G. Innate immunity derived factors as external modulators of the CXCL12-CXCR4 axis and their role in stem cell homing and mobilization. Theranostics. 2013;3:3–10. doi: 10.7150/thno.4621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hiepe F, Dorner T, Hauser AE, Hoyer BF, Mei H, Radbruch A. Long-lived autoreactive plasma cells drive persistent autoimmune inflammation. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:170–8. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tokoyoda K, Egawa T, Sugiyama T, Choi BI, Nagasawa T. Cellular niches controlling B lymphocyte behavior within bone marrow during development. Immunity. 2004;20:707–18. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bi L, Sarkar R, Naas T, Lawler AM, Pain J, Shumaker SL, Bedian V, Kazazian HH., Jr. Further characterization of factor VIII-deficient mice created by gene targeting: RNA and protein studies. Blood. 1996;88:3446–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miao CH, Ye X, Thompson AR. High-level factor VIII gene expression in vivo achieved by nonviral liver-specific gene therapy vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:1297–305. doi: 10.1089/104303403322319381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kasper CK, Aledort L, Aronson D, Counts R, Edson JR, van Eys J, Fratantoni J, Green D, Hampton J, Hilgartner M, Levine P, Lazerson J, McMillan C, Penner J, Shapiro S, Shulman NR. Proceedings: A more uniform measurement of factor VIII inhibitors. Thromb Diath Haemorrh. 1975;34:612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Webster KE, Walters S, Kohler RE, Mrkvan T, Boyman O, Surh CD, Grey ST, Sprent J. In vivo expansion of T reg cells with IL-2-mAb complexes: induction of resistance to EAE and long-term acceptance of islet allografts without immunosuppression. J Exp Med. 2009;206:751–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ye P, Thompson AR, Sarkar R, Shen Z, Lillicrap DP, Kaufman RJ, Ochs HD, Rawlings DJ, Miao CH. Naked DNA transfer of Factor VIII induced transgene-specific, species-independent immune response in hemophilia A mice. Mol Ther. 2004;10:117–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Helden PM, van den Berg HM, Gouw SC, Kaijen PH, Zuurveld MG, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, Aalberse RC, Vidarsson G, Voorberg J. IgG subclasses of anti-FVIII antibodies during immune tolerance induction in patients with hemophilia A. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:644–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hausl C, Ahmad RU, Schwarz HP, Muchitsch EM, Turecek PL, Dorner F, Reipert BM. Preventing restimulation of memory B cells in hemophilia A: a potential new strategy for the treatment of antibody-dependent immune disorders. Blood. 2004;104:115–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parker MJ, Xue S, Alexander JJ, Wasserfall CH, Campbell-Thompson ML, Battaglia M, Gregori S, Mathews CE, Song S, Troutt M, Eisenbeis S, Williams J, Schatz DA, Haller MJ, Atkinson MA. Immune depletion with cellular mobilization imparts immunoregulation and reverses autoimmune diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. Diabetes. 2009;58:2277–84. doi: 10.2337/db09-0557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reipert BM, Allacher P, Hausl C, Pordes AG, Ahmad RU, Lang I, Ilas J, Windyga J, Klukowska A, Muchitsch EM, Schwarz HP. Modulation of factor VIII-specific memory B cells. Haemophilia. 2010;16:25–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith KG, Light A, Nossal GJ, Tarlinton DM. The extent of affinity maturation differs between the memory and antibody-forming cell compartments in the primary immune response. EMBO J. 1997;16:2996–3006. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.2996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slifka MK, Matloubian M, Ahmed R. Bone marrow is a major site of long-term antibody production after acute viral infection. J Virol. 1995;69:1895–902. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1895-1902.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kabashima K, Haynes NM, Xu Y, Nutt SL, Allende ML, Proia RL, Cyster JG. Plasma cell S1P1 expression determines secondary lymphoid organ retention versus bone marrow tropism. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2683–90. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Belnoue E, Pihlgren M, McGaha TL, Tougne C, Rochat AF, Bossen C, Schneider P, Huard B, Lambert PH, Siegrist CA. APRIL is critical for plasmablast survival in the bone marrow and poorly expressed by early-life bone marrow stromal cells. Blood. 2008;111:2755–64. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-110858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Benson MJ, Dillon SR, Castigli E, Geha RS, Xu S, Lam KP, Noelle RJ. Cutting edge: the dependence of plasma cells and independence of memory B cells on BAFF and APRIL. J Immunol. 2008;180:3655–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.3655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peperzak V, Vikstrom I, Walker J, Glaser SP, LePage M, Coquery CM, Erickson LD, Fairfax K, Mackay F, Strasser A, Nutt SL, Tarlinton DM. Mcl-1 is essential for the survival of plasma cells. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:290–7. doi: 10.1038/ni.2527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'Connor BP, Raman VS, Erickson LD, Cook WJ, Weaver LK, Ahonen C, Lin LL, Mantchev GT, Bram RJ, Noelle RJ. BCMA is essential for the survival of long-lived bone marrow plasma cells. J Exp Med. 2004;199:91–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cyster JG. Homing of antibody secreting cells. Immunol Rev. 2003;194:48–60. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hargreaves DC, Hyman PL, Lu TT, Ngo VN, Bidgol A, Suzuki G, Zou YR, Littman DR, Cyster JG. A coordinated change in chemokine responsiveness guides plasma cell movements. J Exp Med. 2001;194:45–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vose JM, Ho AD, Coiffier B, Corradini P, Khouri I, Sureda A, Van Besien K, Dipersio J. Advances in mobilization for the optimization of autologous stem cell transplantation. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50:1412–21. doi: 10.1080/10428190903096701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liles WC, Broxmeyer HE, Rodger E, Wood B, Hubel K, Cooper S, Hangoc G, Bridger GJ, Henson GW, Calandra G, Dale DC. Mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells in healthy volunteers by AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. Blood. 2003;102:2728–30. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liles WC, Rodger E, Broxmeyer HE, Dehner C, Badel K, Calandra G, Christensen J, Wood B, Price TH, Dale DC. Augmented mobilization and collection of CD34+ hematopoietic cells from normal human volunteers stimulated with granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor by single-dose administration of AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. Transfusion. 2005;45:295–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.04222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Christopher MJ, Rao M, Liu F, Woloszynek JR, Link DC. Expression of the G-CSF receptor in monocytic cells is sufficient to mediate hematopoietic progenitor mobilization by G-CSF in mice. J Exp Med. 2011;208:251–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pelus LM, Horowitz D, Cooper SC, King AG. Peripheral blood stem cell mobilization. A role for CXC chemokines. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2002;43:257–75. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Clercq E. The AMD3100 story: the path to the discovery of a stem cell mobilizer (Mozobil). Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77:1655–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.