Abstract

Abnormalities in the ability of cells to properly degrade proteins have been identified in many neurodegenerative diseases. Recent work has implicated Synaptojanin 1 (SynJ1) in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, although the role of this polyphosphoinositide phosphatase in protein degradation has not been thoroughly described. Here we dissected in vivo the role of SynJ1 in endolysosomal trafficking in zebrafish cone photoreceptors using a SynJ1-deficient zebrafish mutant, nrca14. We found that loss of SynJ1 leads to specific accumulation of late endosomes and autophagosomes early in photoreceptor development. An analysis of autophagic flux revealed that autophagosomes accumulate due to a defect in maturation. In addition we found an increase in vesicles that are highly enriched for PI(3)P, but negative for an early endosome marker in nrca14 cones. A mutational analysis of SynJ1 enzymatic domains found that activity of the 5’ phosphatase, but not the Sac1 domain, is required to rescue both aberrant late endosomes and autophagosomes. Finally, modulating activity of the PI(4,5)P2 regulator, Arf6, rescued the disrupted trafficking pathways in nrca14 cones. Our study describes a specific role for SynJ1 in autophagosomal and endosomal trafficking and provides evidence that PI(4,5)P2 participates in autophagy in a neuronal cell type.

Keywords: Synaptojanin1, Arf6, phosphoinositides, autophagy, photoreceptor, zebrafish, neuron

Graphical abstract

Loss of SynJ1 causes late endosomal and autophagic defects in cone photoreceptors. Modulating the activity of the PI(4,5)P2-regulator Arf6a rescues autophagy defects in the absence of SynJ1. We propose that SynJ1 negatively regulates the formation of autophagosome precursors through actions on membrane PI(4,5)P2.

Introduction

Cells must balance synthesis of new proteins with the degradation of old and damaged proteins to maintain their cellular proteome. Neuronal cell types are particularly susceptible to breakdowns in protein homeostasis because they are post-mitotic, long-lived cells. Many neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis show cellular phenotypes that are consistent with abnormalities in protein turnover[1]. In the retina, degeneration of photoreceptors causes blindness[2]. Understanding the proteins and cellular processes that underlie protein turnover is vital to understanding the underlying pathology of these diseases as well as developing treatments. Protein degradation is accomplished by two main pathways; the ubiquitin-proteasome system and the endolysosomal system. Membrane proteins are removed from the plasma membrane by endocytosis. The endocytosed proteins are delivered to early endosomes where they are sorted. Proteins destined for degradation will continue through the endolysosomal pathway, first through late endosomes and finally to the lysosome. Cytosolic proteins can be degraded either by the proteasome or by autophagy[3]. The term autophagy generally refers to macroautophagy, a process in which a double membrane structure forms in the cytoplasm, non-specifically engulfing cytoplasmic contents including proteins and organelles. In order to degrade their contents, autophagosomes must fuse with the lysosome. In yeast, autophagosomes fuse directly with the vacuole. In mammalian systems, autophagosomes can also fuse directly with the lysosome or first fuse with other endosomal compartments, forming an amphisome, before fusing with the lysosome[4].

Important regulators of the endolysosomal pathway are the phosphoinositide (PIP) lipids. The inositol head group of these phospholipids can be phosphorylated at three positions, giving rise to seven different PIP species. The differential subcellular distribution of PIPs in different membranes confers membrane identity and allows the spatial and temporal control of effector proteins to endosomal membranes[5]. The identities, levels, and distributions of PIPs are tightly controlled through the actions of kinases and phosphatases.

Two PIPs, phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate (PI(3)P) and phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate (PI(3,5)P2) are found on membranes of endolysosomal organelles, and play key roles in regulating their formation, maturation and trafficking[6]. PI(3)P is found on early endosomes whereas PI(3,5)P2 is found on late endosomes and lysosomes[7,8]. The production of PI(3)P is also vital for the process of autophagy; knocking out the kinase that produces PI(3)P prevents autophagosomes from forming[9].

Another phosphoinositide suggested to play a role in autophagy is phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2). PI(4,5)P2 is found on the plasma membrane where it plays vital roles in cytoskeletal remodeling, signal transduction, and endocytosis[10]. Recent studies have demonstrated that PI(4,5)P2 is also involved in autophagy in mammalian cells; both in the initial formation of autophagosome precursors [11] as well as in autophagic lysosome reformation [12]. PI(4,5)P2 is synthesized primarily by type 1 phosphadylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinases (PIP5Ks). PIP5K has been demonstrated to be activated by the small GTPase Arf6[13]. Arf6 is also able to stimulate PI(4,5)P2 production indirectly by activating phospholipase D (PLD), that produces phosphatidic acid (PA), a cofactor for PIP5K stimulation[14]. Arf6 has been found to play an important role in membrane trafficking between endosomes and the plasma membrane. Perturbing Arf6 activity through the expression of a constitutively active (CA) mutation results in the accumulation of PI(4,5)P2 positive endosomes that sequester endocytic cargo[15]. Arf6 increases autophagy by regulating the delivery of membranes from the plasma membrane to autophagosome precursors linking the production of PI(4,5)P2 at the plasma membrane to autophagic trafficking[11].

Further evidence for a role of PI(4,5)P2 in autophagy and protein degradation comes from examining the phenotype associated with the loss of the polyphosphoinositide phosphatase Synaptojanin1 (SynJ1). SynJ1 has well characterized role in clathrin-mediated endocytosis where it dephosphorylates of PI(4,5)P2. Knocking out SynJ1 in neurons, results in an inability to uncoat vesicles and a decrease in the pool of synaptic vesicles [16]. Loss of SynJ1 also leads to defects in protein degradative pathways in photoreceptor neurons. These defects include enlarged acidic vesicles, abnormal late endosomes, an increase in autophagosomes as well as an abnormal accumulation of synaptic proteins within photoreceptor cell bodies[17,18]. Alterations in SynJ1 function have been linked to Alzheimer’s [19] and Parkinson’s [20,21] diseases. Importantly, in an Alzheimer’s mouse model, altering SynJ1 expression causes changes in delivery of amyloid beta to lysosomes[22]. Understanding the functional role of SynJ1 in protein turnover in the endolysosomal and autophagic pathways would help us understand the pathologies of these diseases.

The goal of this study was to define the specific trafficking steps altered in the SynJ1-deficient zebrafish mutant nrca14 and to identify the functional role of SynJ1 in these pathways. To dissect the defect in the autophagic/endolysosomal pathway we used multiple strategies that exploit the ability to image fluorescent molecules in live zebrafish. The zebrafish model is also a unique tool to characterize vesicle transport and associated diseases in the retina due to the rapid development of the eye. In zebrafish, photoreceptors develop and become functional long before SynJ1-deficient animals die[23–25].

We found that autophagic and late endosomal trafficking pathways are specifically altered in nrca14 cones early in photoreceptor development and misregulation of these pathways is not a general consequence of compromised photoreceptor function. The accumulation of autophagosomes is due to a defect in autophagosome maturation and an increase in the formation of autophagosome precursors. We also demonstrate that the 5’ phosphatase, but not Sac1, domain of SynJ1 is involved in regulating endolysosomal and autophagic trafficking in cones. Finally we show that altering activity of the small GTPase Arf6a, which is involved in regulating endocytic membrane traffic through actions on PI(4,5)P2, can rescue the autophagy defects in nrca14 cones, but that abnormal late endosomes in nrca14 cones did not respond to modulating Arf6a activity in the same manner. Based on our data, we propose that SynJ1 negatively regulates the formation of autophagosome precursors through actions on membrane PI(4,5)P2.

Results

Loss of SynJ1 specifically disrupts endolysosomal trafficking early during cone photoreceptor development

Cone photoreceptors from 5 days post fertilization (dpf) nrca14 zebrafish larvae, which lack SynJ1, have abnormal endolysosomal and autophagic trafficking [18]. At 5dpf, cone photoreceptors are fully differentiated and functional [26]. To correlate the endolysosomal defects observed in nrca14 cones [18] with initial stages of photoreceptor development, we examined late endosomes and autophagosomes in cone photoreceptors starting at 3dpf. Retinal development is rapid in zebrafish; at 3dpf cone photoreceptors have begun to form outer segments (OSs) but have not formed fully functional synaptic connections. By 4dpf, cone photoreceptors have formed OSs, established synaptic connections, and can reliably respond to visual stimuli [26]. We analyzed fixed retinal sections of wild type (WT) and nrca14 Tg(TαCP:GFP-map1lc3b) and Tg(TαCP:GFP-rab7) larvae (Figure 1A–C); these fish lines express the autophagosome marker GFP-LC3 or the late endosome marker GFP-Rab7 respectively, in cone photoreceptors[18].

Figure 1. Abnormalities in nrca14cones are specific to late endosomes and autophagosomes and appear early in development.

Images of fixed WT and nrca14 retinas from Tg(TαCP:GFP-map1lc3b) (A) and Tg(TαCP:GFP-rab7) (B) larvae at 3 and 4dpf. nrca14 cones contain more LC3 positive puncta than WT cones by 3dpf (C, compare left panels in A). Abnormally enlarged Rab7 structures are present in nrca14 cones by 3dpf (B). Images of fixed WT and nrca14 retinas from 5dpf Tg(TαCP:GFP-Rab5a) larvae (D). There is no difference in the appearance or number of Rab5a positive early endosomes between WT and nrca14. Scale bar=2μm in all images. Graph (C) shows average LC3 puncta per cell at 3dpf or 4dpf, error bars are SEM. n=8 WT larvae and 7 nrca14 larvae on 3dpf and n=8 WT larvae and 9 nrca14 larvae on 4dpf. (*=p-value<0.05, ***=p-value<0.001 as assessed by Mann-Whitney test). Graph (E) shows average Rab5a puncta per cell at 5dpf, error bars are SEM. n=4 WT larvae and 4 nrca14 larvae. (ns=p-value>0.05 as assessed by Mann-Whitney test).

WT cones contain more LC3 positive structures at 3dpf than at 4dpf (2.02±0.14 vs. 0.77±0.07 LC3 puncta/cell, Figure 1A & C). Autophagy and protein degradation have been found to play roles in neuron development [27,28] and our results suggest that similar processes are involved in cone photoreceptor development. At 3dpf, cones lacking SynJ1 already display differences in late endosomes and autophagosomes relative to WT cones (Figure 1A–C). These differences include an increase in the number of LC3 positive puncta (2.02±0.14 vs. 2.89±0.27 LC3 puncta/cell, Figure 1A & C), as well as the presence of enlarged and abnormal Rab7 positive structures (Figure 1B). By 4dpf, the severity of both phenotypes had sharply increased (0.77±0.07 vs. 4.86±0.27 LC3 puncta/cell, Figure 1A, B & C).

In order to determine if an increase in autophagosomes is the primary phenotype of the nrca14 mutation or a characteristic of dysfunctional photoreceptors, we examined the number of GFP-LC3 positive structures in 5dpf pde6cw59 mutant larvae[29] (Figure S1). The pde6cw59 mutation results in cone photoreceptor degeneration. In contrast to the dramatic accumulation of autophagosomes in nrca14 cones, we observed no significant difference in the number of LC3 positive puncta between WT and pde6cw59 mutant cones (0.99±0.08 vs. 0.77±0.13 LC3 puncta/cell, Figure S1B). This indicates that an accumulation of autophagosomes is not an indirect effect of the nrca14 mutation on cone function.

We further investigated whether the defects in nrca14 cones are specific to the late stages of endolysosomal trafficking, we examined the subcellular distribution of early endosomes in WT and nrca14cones. We generated the line Tg(TαCP:GFP-rab5a) that expresses the early endosome marker GFP-Rab5a in cones. We observed no apparent difference in the subcellular distribution of Rab5a positive early endosomes between WT and nrca14 cones at 5dpf (Figure 1D). There was a slight, but not significant decrease in the number of Rab5a positive structures in nrca14 cones (2.94±0.24 vs. 2.16±0.10 Rab5a puncta/cell, Figure 1E). These data show that the trafficking defects in nrca14 cones primarily affect the late endolysosomal pathway and are present at very early stages of cone development.

Maturation of autophagosomes is disrupted in cones lacking SynJ1

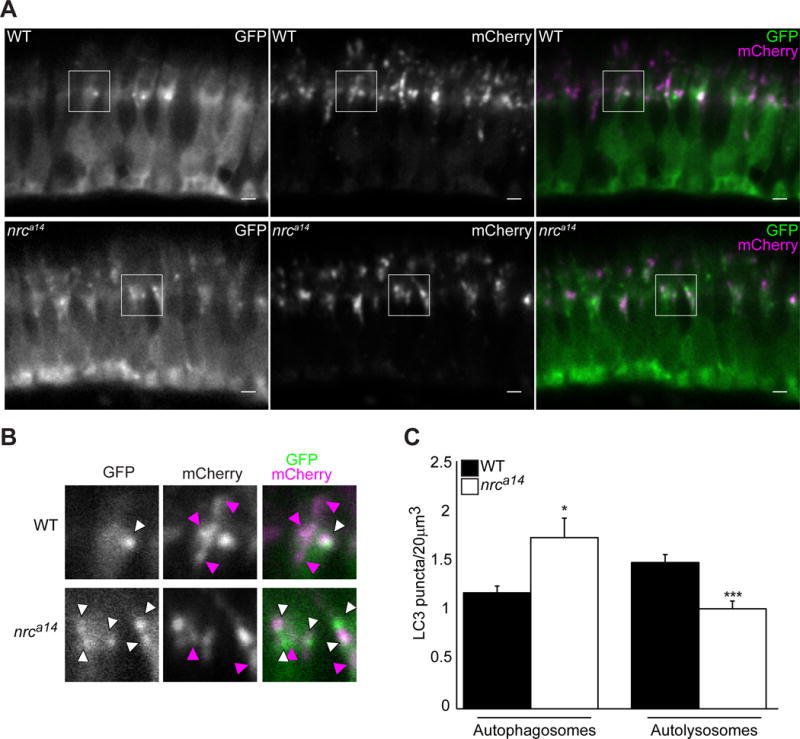

Autophagy is a dynamic process; the increased GFP-LC3 puncta in nrca14 cones could result from increased formation of new autophagosomes, decreased autophagosome maturation and turnover, or a combination thereof. To examine autophagic flux, we generated the fish line Tg(TαCP:mCherry-GFP-map1lc3b) that expresses the tandem construct mCherry-GFP-LC3 in cones. LC3 protein accumulates in autophagosome membranes, resulting in the presence of punctate structures exhibiting both mCherry and GFP fluorescence. In order to degrade their contents, autophagosomes fuse with the acidic endosomes and finally the lysosome, becoming an autolysosome. The autolysosomes have primarily mCherry fluorescence due to quenching and loss of the pH sensitive GFP signal in the tandem construct [30].

In 5dpf WT cones expressing mCherry-GFP-LC3, we observed GFP signal that was primarily cytosolic with a few punctate structures, similar to what we have previously observed in the Tg(TαCP:GFP-map1lc3b) fish line (Figure 2A & B, top panels, white arrowheads). The mCherry signal concentrated in punctate structures in the inner segments (ISs) of WT cones (Figure 2A & B, top panels, magenta arrowheads). As expected, nrca14 cones expressing mCherry-GFP-LC3 displayed more GFP positive autophagosomes than WT cones (1.75±0.32 vs. 1.19±0.15 GFP+, mCherry+ puncta/20um3, Figure 2C). Although we observed the presence of autolysosomes in nrca14 cone ISs, the number of autolysosomes compared to WT was decreased (1.02±0.17 vs. 1.50±0.16 GFP-, mCherry+ puncta/20um3, Figure 2C). We have previously reported that abnormal acidic compartments accumulate in nrca14 cones, suggesting that the decrease in autolysosomes we observe here is not due to defects in acidification of endolysosomal compartments in nrca14 cones[18]. Together, these results indicate a defect, but not complete block, in the ability of autophagosomes to fuse with acidic compartments in nrca14 cones.

Figure 2. Maturation of autophagosomes is blocked in nrca14cones.

Expression of the tandem mCherry-GFP-LC3 probe in cones of WT and nrca14 5dpf larvae. In WT photoreceptors autolysosomes (magenta-only puncta) were visible (A, top panel). Fewer magenta-only puncta were visible in nrca14cones (A, bottom panel), indicating that the LC3 positive autophagosomes had not fused with an acidic compartment. (B) Shows enlargement of areas shown in boxes in (A). White arrow heads indicate GFP+, mCherry+ autophagosomes, magenta arrowheads point to GFP-, mCherry+ autolysosomes. Scale bar=2μm in A. Graph in (C) shows average number of autophagosomes (GFP+, mCherry+) and autolysosomes (GFP-, mCherry +) per 20um3. Error bars are SEM and n=7 WT larvae and 6 nrca14 larvae. (***=p-value<0.001, *=p-value<0.05 respectively as assessed by Mann-Whitney test).

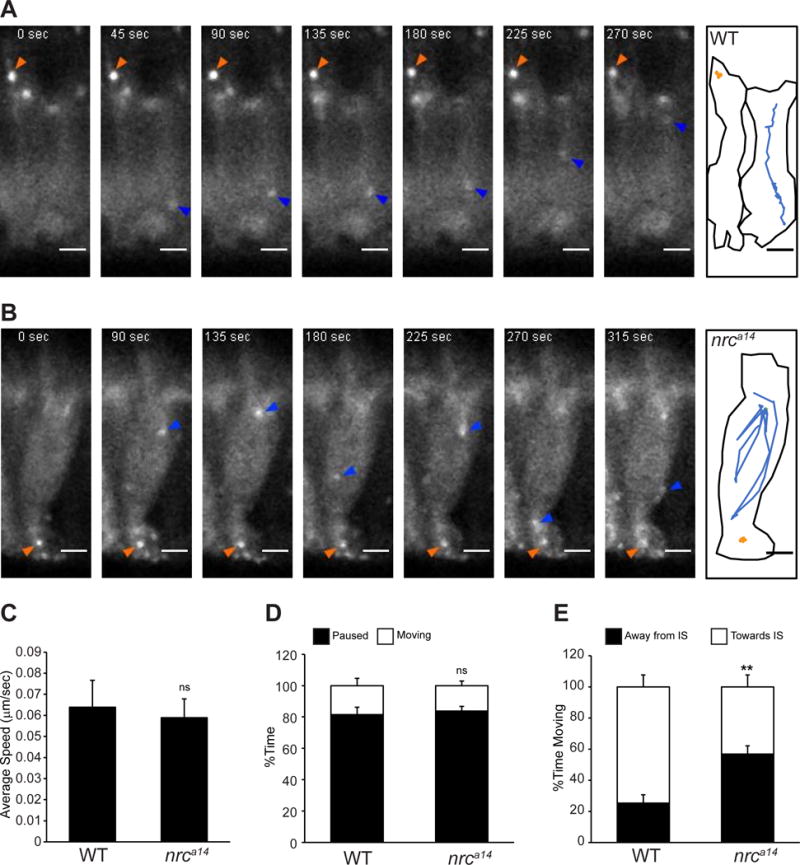

An accumulation of autophagosomes and defect in autophagosome-lysosome fusion could occur due to the inability of autophagosomes to move throughout the cell. To examine the dynamics of LC3 positive autophagosomes in WT and nrca14 cones we used live time-lapse confocal microscopy. We found that LC3-labeled autophagosomes were highly mobile in both WT and nrca14 cones (Figure 3 and Supplementary Movies). The movements of autophagosomes in WT and nrca14 cones were qualitatively similar. Vesicles traversed between the IS and synapse and also displayed short range movements within the IS or synapse. We did not detect autophagosome transport within the OS. We found that there was no difference in the average speed of LC3 positive vesicles (Figure 3C), or the relative amount of time they spent moving (Figure 3D). We did observe a change in the directionality of LC3 positive vesicles between WT and nrca14 cones; whereas vesicles in WT cells often stopped or disappeared after moving towards the ISs (Figure 3A and Supplementary movie 1 blue arrow), vesicles in nrca14 cones often reversed direction after reaching the IS (Figure 3A and Supplementary movie 2 blue arrow). This observation was reflected in the relative amount of time LC3 positive vesicles spent moving towards or away from the IS in WT and nrca14 cones (Figure 3E). These data demonstrate that the block in autophagosome maturation observed in nrca14 cones does not occur due to a loss of autophagosome mobility.

Figure 3. Mobility of autophagosomes is not reduced in nrca14 cones.

Live time-lapse images of Tg(TαCP:GFP-map1lc3b) 5dpf zebrafish larvae show that autophagosomes are highly mobile in both WT and nrca14 cones. Images were acquired in 5 second frame intervals. Select time points are shown for WT (A) and nrca14 (B) cones. A schematic showing the outline of the cell(s) and movement of two representative LC3 positive particles are shown for each genotype. Puncta in nrca14 cones exhibit similar movements to those found in WT. The average speed (C) and relative amount of time LC3 positive vesicles were mobile (D) is the same in WT and nrca14 cells. In nrca14 cells, LC3 vesicles spent significantly more time moving away from the IS than in WT cells (E). Error bars are SEM and n=15 vesicles from 3 WT larvae and 15 vesicles from 3 nrca14 larvae. (ns=p-value>0.05, **=p-value<0.01 as assessed by Mann-Whitney test). Scale bar=2μm.

PI(3)P positive vesicles lacking endosome markers accumulate in cones lacking SynJ1

To further dissect the vesicle trafficking defects in nrca14cones, we analyzed the subcellular distribution of PI(3)P and PI(3,5)P2. These two PIPs are found throughout the endolysosomal system and serve as markers of different endocytic compartments. We generated the transgenic fish lines Tg(TαCP:YFP-2XFYVE) and Tg(TαCP:mCherry-ML1NX2) that express a PI(3)P probe [7] and PI(3,5)P2 probe [31] respectively under the cone specific TαCP promoter. In metazoan cells, PI(3)P is found primarily in the membranes of early endosomes and autophagosomes [7,32]. In WT cones the PI(3)P probe localized to small punctate structures at the synapses and larger punctate structures in the IS (Figure 4A left panel). In nrca14 cones, we observed a similar subcellular distribution of PI(3)P containing structures although the number of puncta, particularly at synaptic terminals, was increased (Figure 4A right panel).

Figure 4. nrca14 cone photoreceptors have an increased number of PI(3)P positive puncta, but no change in distribution of PI(3)P.

(A). PI(3)P was visualized in WT and nrca14 Tg(TαCP:YFP-2XFYVE) transgenic larvae at 5dpf. The PI(3)P probe localizes to punctate structures in the IS and synaptic terminals of both WT and nrca14 cones. More PI(3)P positive puncta are visible at the synaptic terminals of nrca14 cones relative to WT cones. PI(3)P was marked using Tg(TαCP:tagRFPt-2XFYVE) in 5dpf cones expressing GFP-LC3 (B), GFP-Rab5a (C) or GFP-Rab7 (D). Examples of puncta with only GFP signal, only tagRFPt signal, or both signals are denoted by green, magenta or white arrowheads respectively. (E) Percent colocalization of indicated marker with 2XFYVE. (F) Percent colocalization of the 2XFYVE probe with indicated marker. We found no significant difference in the percent colocalization of either LC3, Rab5a or Rab7 with 2XFYVE between WT and nrca14 cones (E & F). Error bars are SEM and n=7–8 WT larvae and 4–6 nrca14 larvae. (ns=p-value>0.05 as assessed by Mann-Whitney test). Scale bar=2μm.

We further characterized the subcellular distribution of PI(3)P in WT and nrca14 cone photoreceptors by analyzing the colocalization of this PIP with our markers for autophagosomes, and early and late endosomes. We generated the fish line Tg(TαCP:tRFP-t-2XFYVE) which expresses a red-fluorescent protein tagged version of the PI(3)P marker shown in Figure 4A. We quantified colocalization as percent pixels of one probe that overlapped with the second probe after background intensity corrections (refer to Materials and Methods section for description of analysis) and found that the relative colocalization of the PI(3)P probe with LC3-positive autophagosomes, early endosomes, and late endosomes in zebrafish photoreceptors agreed with the distribution of this probe in mammalian cells (Figure 4F) [7]. We first looked at the colocalization between PI(3)P and our autophagosome marker, LC3 (Figure 4B top panels). The synthesis of PI(3)P occurs early in autophagosome biogenesis, whereas lipidation and concentration of LC3 in the membrane of autophagosomes occurs at later stages[33]. The PI(3)P marker 2XFYVE has been found to colocalize with LC3 in Drosophila melanogaster [34], but to varying degrees in mammalian cells[35]. In WT zebrafish cones, we found that very few LC3 positive puncta were also positive for PI(3)P (Figure 4B, green arrowheads). Interestingly, puncta that were positive for both PI(3)P and LC3 were often found at synaptic terminals (Figure 4B, white arrowheads), whereas PI(3)P-negative, LC3-positive autophagosomes were more often found in the ISs where lysosomes reside (Figure 4B, green arrowheads). These data suggests that the amount of PI(3)P signal on LC3-positive autophagosomes may reflect their maturation status. In nrca14 cones we observe a similar co-localization pattern of LC3 and PI(3)P (11.9±1.3% colocalization of LC3 with 2XFYVE in WT vs. 15.3±1.4% in nrca14, Figure 4E); most of the LC3-positive puncta were negative for PI(3)P (Figure 4B, green arrowheads). Most of PI(3)P puncta in nrca14 cones were LC3-negative similar to WT (4.2±0.3% colocalization of 2XFYVE with LC3 in WT vs. 4.2±0.2% in nrca14, Figure 4B&F), indicating that these vesicles either represent structures in the endocytic system, or immature autophagosomes that have not yet acquired LC3.

Next, we investigated colocalization between PI(3)P and our early endosome marker, Rab5a. As expected, PI(3)P is found on Rab5a early endosomes in both WT and nrca14 cones (Figure 4C, examples shown by white arrowheads). In nrca14 cones we observed that many of the PI(3)P positive puncta were negative for Rab5a compared to WT cones (Figure 4C, examples shown by magenta arrowheads). We found a decrease in the percent colocalization of the 2XFYVE marker with Rab5a in nrca14 cones compared to WT (9.9±1.9% colocalization of 2XFYVE with Rab5a in WT vs. 6.9±1.0% in nrca14, Figure 4C&F) suggesting that the additional PI(3)P positive puncta are not early endosomes. In the endocytic pathway PI(3)P is found primarily on early endosomes, but is also found on the luminal vesicles of multivesicular bodies[7], and localizes to Rab7 positive membranes[36]. In both WT and nrca14 cones we observed that some Rab7 positive structures are positive for PI(3)P (Figure 4D, white arrowheads). Overall, the same proportion of 2XFYVE structures were positive for Rab7 in WT and nrca14 cells (18.6±1.5% colocalization of 2XFYVE with Rab7 in WT vs. 22.0±2.0% in nrca14, Figure 4D&F) consistent with an increase in the overall increase in Rab7 vesicles observed in nrca14 cones. These results indicate that many of the additional PI(3)P puncta observed in nrca14 cones are not early or late endosomes, suggesting that they likely represent early autophagosomal structures.

PI(3,5)P2 is found on late endosomes and lysosomes and has been found to colocalize with markers for both immature and mature autophagosomes [6,8,37]. In WT photoreceptors the PI(3,5)P2 probe localized to punctate structures in the IS and showed diffuse cytoplasmic staining (Figure 5A, left panel). In nrca14 photoreceptors we found a very similar subcellular distribution; the probe localized to punctate structures and also showed diffuse signal in the cytoplasm (Figure 5A, right panel). We looked at the colocalization of PI(3,5)P2 with autophagosomes and late endosomes. In WT cones, we rarely observed overlap of PI(3,5)P2 and LC3 (Figure 5B). In nrca14 cones, LC3 and PI(3,5)P2 colocalized more often (Figure 5B, bottom panels, white arrowhead). These structures are most likely mature autophagosomes that have not fused with acidic compartments to quench the GFP-LC3 signal, consistent with the observed decrease in autolysosomes (Figure 2C). We found that PI(3,5)P2 positive structures colocalized with punctate Rab7 positive structures in both WT and nrca14 cones (Figure 5C, white arrowheads). We did not observe the accumulation of PI(3,5)P2 on enlarged Rab7 structures in nrca14 cones, indicating that an accumulation of PI(3,5)P2 is not causing the formation of these abnormal structures.

Figure 5. The distribution of PI(3,5)P2 positive late endosomal compartments is the same in WT and nrca14 cells.

(A) The PI(3,5)P2 probe ML1NX2 localizes to small, punctate structures in the ISs of WT and nrca14 cone photoreceptors in 5dpf Tg(TαCP:mCherry-ML1NX2) transgenic larvae. (B) Some PI(3,5)P2 puncta overlap with LC3 positive puncta in nrca14 but not WT cones, agreeing with the decrease in acidic LC3-positive structures observed in Figure 2. (C) The PI(3,5)P2 partially overlaps with Rab7 puncta in both WT and nrca14 cone photoreceptors, but is not found on abnormal Rab7 structures in nrca14 cones. Scale bar=2μm in all images.

The distributions of PI(4,5)P2 and PI(4)P are not altered in the absence of SynJ1

We analyzed the subcellular distribution of the canonical vertebrate SynJ1 substrates, PI(4,5)P2 and PI(4)P to determine if a change in distribution of these two PIPs could account for the trafficking defects in nrca14 photoreceptors. We transiently expressed the genetically encoded probes PLCδ-PH[38] and FAPP1-PH[39] to detect PI(4,5)P2 and PI(4)P respectively. In WT photoreceptors, PI(4,5)P2 was localized throughout the plasma membrane and concentrated at synaptic terminals (Figure 6A & B). Interestingly, although we observed the PLCδ-PH signal extending up until the ends of the calycal processes at the apical end of the IS, we did not detect PI(4,5)P2 in photoreceptor OSs (n>100 cells). Between 3 and 6dpf, the subcellular distribution of PI(4,5)P2 in WT and nrca14 photoreceptors appeared the same (Figure 6B). We did not observe an accumulation of PI(4,5)P2 on intracellular structures that could be attributed to abnormal late endosomes or autophagosomes in nrca14 photoreceptors.

Figure 6. PI(4,5)P2 and PI(4)P distributions are not altered in nrca14 cones.

The PI(4,5)P2 probe GFP-PLCδ-PH was expressed in photoreceptors using the crx promoter (A, B). In WT cells at 5dpf this probe localized to the plasma membrane and concentrated at synapses, but did not extend above the mitochondria (magenta) into the OS (A). The PLCδ-PH probe showed the same distribution in nrca14 photoreceptors from 3dpf to 6dpf. PI(4)P was visualized with the probe RFP-FAPP1-PH (C). In both WT and nrca14 photoreceptors at 5dpf, the RFP-FAPP1-PH probe (magenta) overlapped with the medial Golgi marker Man2a-GFP (green). There was no difference in the subcellular distribution of PI(4)P between WT and nrca14 photoreceptors. Scale bar=2μm in all images.

PI(4)P is found predominantly on the Golgi apparatus [40]. We transiently expressed the PI(4)P probe, RFP-FAPP1, in cones of WT and nrca14 larvae expressing a Golgi marker. This line, Tg(crx:man2a-GFP), expresses GFP fused to the medial Golgi targeting sequence from Mannosidase2a (Man2a) in photoreceptors and retinal bipolar cells [18]. Although we observed variability in the distribution of the RFP-FAPP1 PI(4)P probe in transient expression experiments, we did not observe consistent differences in PI(4)P subcellular distribution between WT and nrca14 photoreceptors (Figure 6C). The probe localized to the Golgi and partially overlapped with the medial Golgi marker in both WT and nrca14 photoreceptor cells (Figure 6C). Thus, misaccumulation of PI(4)P or PI(4,5)P2 on endosomal structures within cones does not explain SynJ1 trafficking defects.

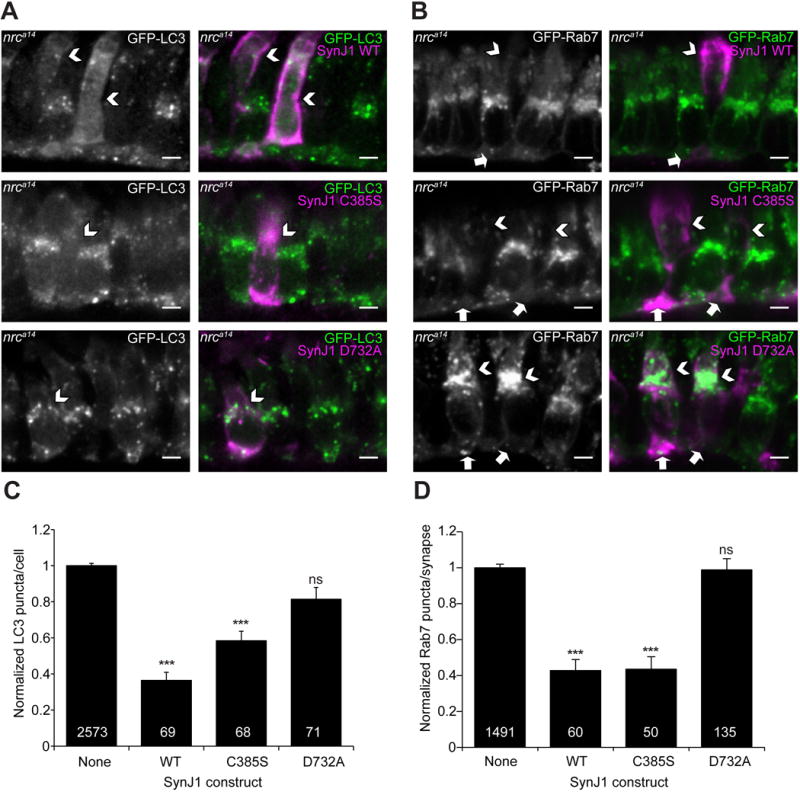

The activity of the 5’phosphatase domain, but not Sac1 domain, of SynJ1 is required for proper autophagic and endolysosomal trafficking

SynJ1 contains two enzymatic PIP phosphatase domains. To define the enzymatic activity of SynJ1 involved in regulating the endolysosomal and autophagic systems in photoreceptors, we performed rescue experiments in nrca14 cones with WT SynJ1 or SynJ1 containing mutations in the two conserved phosphatase domains. The 5’ phosphatase domain has specific activity towards 5’ phosphates, and the less-specific Sac1 domain has both 3′- and 4′-phosphatase activities [41]. We transiently expressed FLAG-tagged zebrafish SynJ1 constructs (SJCs) in cones of nrca14 Tg(TαCP:GFP-map1lc3b) and Tg(TαCP:GFP-rab7) larvae. Injection of DNA constructs into zebrafish larvae results in mosaic expression [42], allowing us to examine both SJC positive and negative cones within the same retina. Rescue of the autophagosome and late endosome phenotypes by the SJCs in nrca14 cones was assessed qualitatively by examining the morphology of Rab7 vesicles and quantitatively by counting the total number of LC3 puncta or synaptic Rab7 puncta per cell. The number of puncta in the SJC expressing cells was normalized to the number of puncta in the non-SJC expressing cells in the same larvae.

We observed that WT and mutant SynJ1 localized to the plasma membrane and was concentrated at synaptic terminals (Figure 7 and S2). We did not observe that any of the SJCs localized to intracellular structures. In addition, expression of WT and mutant SynJ1 did not affect the appearance or number of autophagosomes or late endosomes in WT cones (Figure S2).

Figure 7. 5’phosphatase activity of SynJ1 is required to rescue late endosome and autophagy phenotypes in nrca14 cones.

Fixed sections of 5dpf nrca14 Tg(TαCP:GFP-map1lc3b) (A) and Tg(TαCP:GFP-rab7) (B) larvae transiently expressing SJCs in cones. WT SynJ1 was able to significantly rescue both the late endosome and autophagosome abnormalities in nrca14 cones. SynJ1 lacking SacI catalytic activity (C385S) also significantly rescued the late endosome and autophagosome defects. In contrast, the D732A construct was not able to rescue either the late endosome or autophagosome phenotypes. Arrows point to SJC expressing cells (magenta in merge). Scale bar=2μm in all images. Results were quantified by counting the number of total LC3 puncta (B) or Rab7 synaptic puncta (D) in the SJC expressing cells and normalized to the number of puncta in the non-SJC expressing cells in the same nrca14 larvae. Graph in B shows average normalized LC3 puncta per cell, and Graph in D shows average normalized synaptic Rab7 puncta per cell. Error bars are SEM and n≥50 cells for all conditions (exact n shown on graph). The rescue of both the total LC3 puncta and Rab7 synaptic puncta was significant for the WT and C385S SJCs, but not for the D732A SJC. (***=p-value<0.001 by One-Way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison correction).

Expression of WT SynJ1 in nrca14 cones significantly rescued the number of LC3 puncta (64±4% reduction in LC3 puncta, Figure 7A & C), synaptic Rab7 puncta (57±6% reduction in synaptic Rab7 puncta, Figure 7B & D) and the abnormally enlarged Rab7 structures in nrca14 ISs. Late endosomes appeared punctate in nrca14 cones expressing the WT SJC, similar to the Rab7 structures observed in WT cones (Figure 7B). Further, we observed significant rescue of both aberrant vesicles in ISs and synaptic morphology by EM analysis of nrca14 mutant cones stably expressing a GFP-SynJ1 transgene (Figure S3).

Next we determined whether SynJ1 with a point mutation in the Sac1 catalytic domain could rescue the endolysosomal defects in nrca14 cones. The Sac1 domain of zebrafish SynJ1 contains a conserved CX5R(T/S) catalytic motif [43]. Mutating the conserved cysteine to serine results in a catalytically dead Sac1 domain in yeast [44], mouse [45] and human[20] Synaptojanin homologues. We generated the homologous C385S mutation in the Sac1 domain of zebrafish SynJ1. We found that the Sac1 mutant SJC was able to significantly rescue the total number of LC3 puncta (42±5% reduction in LC3 puncta, Figure 7C). The degree of rescue compared to WT SynJ1 was slightly reduced, however; this difference was not statistically significant. The Sac1 mutant also rescued the number of synaptic Rab7 puncta (56±7% reduction in synaptic Rab7 puncta, Figure 7D) in nrca14 cones, as well as the appearance of abnormal Rab7 structures in cone ISs (Figure 7A & B middle panels). This observation indicates that the Sac1 phosphatase activity of SynJ1 is not required for proper endolysosomal and autophagic trafficking in cones. This rules out a direct role of SynJ1 in regulating PI(4)P or PI(3)P in endolysosomal and autophagic trafficking.

Finally, we generated a catalytically dead D732A mutation in the 5’ phosphatase domain of zebrafish SynJ1. The conserved motif XWXGDXN(F/Y)R is found in many 5’ phosphatases [46] and mutating the aspartate to alanine results in the loss of 5’ phosphatase activity of yeast [47], worm[48], and mouse [45] Synaptojanin. In contrast to the Sac1 C385S point mutation, the D732A mutation was not able to rescue either the LC3 (Figure 7C) or Rab7 (Figure 7D) phenotype in nrca14 cones. The nrca14 cones expressing the D732A SJC still exhibited an accumulation of GFP-LC3 puncta as well as abnormal Rab7 structures (Figure 7A & B bottom panels). This result indicates that SynJ1 is required to regulate a PIP species with a 5’ phosphate, and that defects in this process are responsible the observed late endosome and autophagosome abnormalities observed in nrca14 cones.

The PI(4,5)P2 regulator, Arf6, affects autophagy in cone photoreceptors and rescues trafficking defects caused by loss of SynJ1

Our mutational analysis of SynJ1 has indicated that SynJ1 regulates a PIP with a 5’ phosphate. Although our earlier experiments did not detect an obvious change in the subcellular distribution of PI(4,5)P2, this PIP is the canonical substrate of SynJ1 in vertebrate cells and is a likely candidate to explain the abnormalities we observe in nrca14 cones. In order to determine if alterations in the level of PI(4,5)P2 are involved in the trafficking defects observed in nrca14 cones, we altered the activity of the small GTPase Arf6. Arf6 is involved in controlling PI(4,5)P2 levels by activating PIP5K at the plasma membrane[13,15]. Additionally, this protein has been implicated in the formation of pre-autophagosomal membranes through its effects on PI(4,5)P2[11]. This small GTPase also has characterized mutations that result in constitutively active (CA) or dominant negative (DN) activity.

Similar to our SynJ1 rescue experiments, we cloned the zebrafish Arf6 homologue, Arf6a, from zebrafish cDNA. We then generated CA and DN constructs, transiently expressed these constructs in cones of nrca14 Tg(TαCP:GFP-map1lc3b) and Tg(TαCP:GFP-rab7) larvae and assessed the number of LC3 or Rab7 positive structures. When expressed in cones, the localization of the Arf6a constructs agreed with published data [14,15,49,50].

Previous studies have shown that the small GTPase Arf6 is involved in the formation of autophagosome precursors through both PIP5K and Phospholipase D (PLD)[11]. We found that expressing WT Arf6a had no significant effect on the number of LC3-positive autophagosomes in either WT or nrca14 cones (Figure 8). Expression of a GTP-hydrolysis defective, CA mutant Arf6a-Q67L has previously been reported to decrease the number of pre-autophagosomal structures and autophagosomes in cell culture, presumably by sequestering PI(4,5)P2 in endosomal structures[11]. When expressed in WT cones, the Arf6a Q67L mutant had no effect on the number of LC3 positive autophagosomes (Figure 8A & C). In nrca14 cones, expression of Arf6a Q67L resulted in a significant decrease in the number of autophagosomes (38±7% reduction in LC3 puncta, Figure 8B & C). We found that expression of a GDP-bound DN Arf6 construct, Arf6 T44N, was able to significantly reduce the number of autophagosomes in both WT (33±9% reduction) and nrca14 (29±6% reduction) cones (Figure 8C). Finally, we tested whether an Arf6a mutant with defective PLD binding, N48R, would affect the autophagy phenotype in nrca14 mutants. The Arf6 N48R mutation has been shown to decrease the formation of LC3-II in Bafilomycin-treated cells[11]. We found that Arf6a N48R had no effect on autophagy in WT cones, but significantly rescued the number of LC3 puncta in nrca14 cones (36±6% reduction). These results indicate that Arf6a and SynJ1 are acting in the same pathway to modulate autophagy in cone photoreceptors. As Arf6 has been shown to positively regulate levels of the canonical SynJ1 substrate PI(4,5)P2 through actions on PIP5K and PLD, it is likely that both Arf6 and SynJ1 are acting on autophagy through this lipid.

Figure 8. Altered Arf6a activity can rescue autophagy phenotype in nrca14 cones.

Fixed sections of 5dpf WT (A) and nrca14 (B) Tg(TαCP:GFP-map1lc3b) larvae transiently expressing Arf6a-tagRFPt construct in cones. WT Arf6a did not significantly affect the number of autophagosome in WT or nrca14 cones. CA Arf6a Q67L significantly rescued autophagosome defects nrca14 cones. DN GDP-bound Arf6a T44N rescued the autophagy phenotype in nrca14 cones, and decreased the number of autophagosomes in WT cones. DN PLD-binding deficient Arf6a N48R also significantly rescued the autophagy defect in nrca14 cones. Arrowheads point to Arf6a expressing cells (magenta in merge). Scale bar=2μm in all images. Results were quantified by counting the number of total LC3 puncta in the Arf6a expressing cells and background corrected using the number of puncta in the non-Arf6a expressing cells in the same larvae. Graph in C shows average corrected LC3 puncta per cell. Error bars are SEM and n≥50 cells for all conditions (exact n shown on graph). (*=p-value<0.05, ***=p-value<0.001 relative to cells not expressing Arf6a in nrca14, #= p-value<0.05 in WT, by One-Way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison correction).

We also examined the effects of Arf6 on the late endosome phenotype in nrca14 mutants (Figure 9). Arf6 has been shown to play a role in sorting and maturation steps of late endosomes[51]. We found that expression of WT Arf6 had no effect on the number of synaptic Rab7 vesicles in either WT or nrca14 cones. Expression of the Arf6 Q67L mutant resulted in a significant increase in the number of Rab7 positive vesicles at the synapses of WT cones (65±22% increase in synaptic Rab7 puncta, Figure 9C). Expression of Arf6 Q67L had the opposite effect in nrca14 cones; it resulted in a significant decrease in the number of synaptic Rab7 positive vesicles (35±7% reduction, Figure 9C). To our knowledge the effect of the Arf6 Q67L of Rab7 positive vesicles has not been studied. It has been reported that expression of Arf6 Q67L results in the entrapment of cargo in Arf6-Q67L positive endosomal structures [15,52]. It is possible that the presence of this trapped cargo results in an upregulation of the degradative pathway, resulting in the presence of an increased number of Rab7 positive compartments in WT cones and possibly ameliorating the protein degradation block observed in nrca14 cones. Further work will need to be done to test this idea, and understand the effects of this Arf6 construct on late endosomes. Despite significantly rescuing the autophagy phenotype, expression of the dominant negative mutants Arf6 T44N or Arf6 N48R had no significant effects on the number of synaptic Rab7 vesicles in either WT or nrca14 cones (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Constitutively active Arf6a Q67L rescues late endosome phenotype in nrca14 cones.

Fixed sections of 5dpf WT (A) and nrca14 (B) Tg(TαCP:GFP-rab7) larvae transiently expressing Arf6a-tagRFPt construct in cones. WT and DN Arf6a did not significantly affect the number of synaptic Rab7 puncta in WT or nrca14 cones. CA Arf6a Q67L significantly rescued the synaptic Rab7 puncta in nrca14 cones. Arf6a Q67L significantly increased the number of synaptic Rab7 puncta in WT cones. Arrowheads point to Arf6a expressing cells (magenta in merge), arrows point to Arf6a-expresssing synaptic terminals. Scale bar=2μm in all images. Results were quantified by counting the number of synaptic Rab7 puncta in the Arf6a expressing cells and background corrected using the number of puncta in the non-Arf6a expressing cells in the same larvae. Graph in C shows average corrected synaptic Rab7 puncta per cell. Error bars are SEM and n≥50 cells for all conditions (exact n shown on graph). (*=p-value<0.05, ***=p-value<0.001 in nrca14, #= p-value<0.05 in WT relative to cells not expressing Arf6a by One-Way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison correction).

These Arf6 experiments revealed that Arf6 and SynJ1 act in the same pathway to modulate autophagy, implicating PI(4,5)P2 in this process. Additionally we observed that the dominant negative T44N and N48R mutations rescue the autophagy phenotype, but not the Rab7 phenotype suggesting that the two phenotypes are distinct and not caused by one another. However, caution needs to be taken in interpreting these results, as expression levels of DN constructs as well as the sensitivity of the LC3 and Rab7 assays may differ.

Together our data show that SynJ1 is acting on a PIP species with a 5’ phosphate to cause changes in both the formation of PI(3)P positive structures, that may be pre-autophagosomes, as well as the maturation of autophagosomes. Because altering the activity Arf6a is able to rescue the nrca14 autophagy phenotype, we propose that the most likely identity of the D-5 SynJ1 substrate is PI(4,5)P2. We have established a specific role for SynJ1 in endolysosomal trafficking, defined the functional activity required to regulate this process and implicated PI(4,5)P2 in the formation of autophagosomes in cone photoreceptor neurons.

Discussion

We have presented evidence that SynJ1 plays a novel role in autophagic and endolysosomal pathways. Zebrafish cones lacking SynJ1 display dramatic accumulations of autophagosomes and abnormal late endosomes. These abnormalities appear early in photoreceptor development, prior to the onset of synaptic activity. In addition we have shown that these defects are specific to protein degradation pathways, and not a general consequence of altered photoreceptor function. We found evidence for both a defect in maturation as well as an increase in formation of autophagosomes. The proper regulation of both the autophagic and late endosomal phenotypes requires activity of the 5’ phosphatase domain of SynJ1. Finally we performed rescue experiments in nrca14 cones with the PI(4,5)P2 regulator Arf6 and found that modulation of Arf6 activity could rescue the accumulation of autophagosomes by inhibiting their formation. These findings support the idea that SynJ1 negatively regulates the formation of autophagosome precursors through actions on membrane PI(4,5)P2.

SynJ1 is well known for its key role in neurons in clathrin-mediated endocytosis both pre- and post-synaptically [16,53]. However, recent studies have also uncovered roles for this PIP phosphatase in cellular functions other than clathrin-mediated endocytosis. In an Alzheimer mouse model, SynJ1 knockdown resulted in accelerated delivery of amyloid beta (Aβ) to lysosomes[22]. Further, our recent work shows that in photoreceptors, SynJ1 plays a role in vesicle trafficking distinct from synaptic vesicle recycling, and is specifically involved in the autophagic and endolysosomal pathways[18]. In addition, the involvement of SynJ1 in protein degradation pathways could help explain the pathology observed in a recently identified human synj1 mutation in a young patient with a taupathy[54] as well as the involvement of SynJ1 in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease [19–21,55]. The study we present here represents a detailed mechanistic analysis of SynJ1 function in protein degradation trafficking pathways.

In order to link the enzymatic activity of SynJ1 and autophagic and late endosomal trafficking pathways, we conducted a mutational analysis of the two SynJ1 phosphatase domains. The 5’ phosphatase specifically removes phosphates from the 5’ position of the inositol ring. The Sac1 domain of SynJ1 is less specific and acts on phosphates at both the 3′ and 4′ positions on the inositol ring [41,45]. Previous studies examining the roles of the different SynJ1 domains have focused on the contribution of these domains in synaptic vesicle recycling. While both enzymatic domains play roles in this process, loss of 5’ phosphatase activity had more severe consequences than loss of Sac1-like activity and caused impaired endocytosis defects over a broader range of stimuli [45,48]. Further, recent studies examining patients with early onset Parkinson’s disease have discovered linked mutations in the Sac1 domain of SynJ1 and thus prolonged loss of this activity appears to also have dire effects [20,21]. Our work indicates that loss of the 5’ phosphatase activity of SynJ1 is more detrimental than the loss of Sac1 activity in endolysosomal trafficking in cone photoreceptors. We found that constructs lacking 5’ phosphatase activity could not rescue the accumulation of late endosomes and autophagosomes in nrca14 cones; however constructs lacking activity of the Sac1 domain could significantly rescue these phenotypes. Our data revealed a slight (but not significant) impairment in the ability of SynJ1 lacking Sac1 activity to rescue the accumulation of autophagosomes relative to WT SynJ1. Overall, our results indicate that a PIP with a 5’ phosphate is likely involved in the pathology characterized in this study.

The plasma membrane has been found to be a source of membranes for the formation autophagosome precursors that are positive for ATG16L, a protein involved in the initial steps of autophagosome biogenesis, but negative for LC3[56]. Increasing PI(4,5)P2 on the plasma membrane leads to an increase in both LC3 negative autophagosome precursors as well as LC3 positive autophagosomes[11]. As PI(4,5)P2 is a known substrate of SynJ1, it is possible that an increase in PI(4,5)P2 in nrca14 cones photoreceptors could be the cause of the defects in autophagy. We did not detect any changes in PI(4,5)P2 using the PLC-δ-PH probe; however changes in levels of PI(4,5)P2 are difficult to quantify with this probe. As an alternate strategy to determine if PI(4,5)P2 is involved in the disrupted trafficking pathways in nrca14 cones we altered the activity of the small GTPase Arf6. This small GTPase has been shown to play numerous roles in endocytic trafficking [15,49,57], and has recently been linked to the formation of autophagosomes through its actions on PI(4,5)P2 levels[11].

We found that altering Arf6 activity significantly rescued the autophagy defects observed in nrca14 cones. Overexpression of the constitutively active Arf6 mutant Q67L results in the formation of endosomal structures that accumulate PI(4,5)P2 and sequester endocytic cargo[15]. The Arf6 Q67L mutant also decreases the number of autophagosomes in both basal and starvation conditions on cell culture[11]. We observed a similar decrease in the number of autophagosomes in nrca14 cones expressing Arf6a Q67L. Knocking down Arf6 protein or expression of a PLD-binding deficient mutant have also been shown to decrease autophagy[11]. We overexpressed a GDP-locked Arf6a mutant, T44N, as well as a PLD-binding deficient mutant Arf6a, N48R, and observed rescue of the nrca14 autophagy phenotype.

These results indicate that the increased accumulation of autophagosomes in nrca14 cones results from a pathway that can be altered by both Arf6 and SynJ1, implicating PI(4,5)P2. Further support of a model in which SynJ1 negatively regulates the delivery of endocytic membranes to forming autophagosomes comes from a recent study of the role of Endophilin in clathrin independent endocytosis[58]. They observed that overexpression of Synaptojanin inhibited recruitment of Endophilin to the plasma membrane, whereas knockdown of Synaptojanin had the opposite effect. They concluded that Synaptojanin negatively regulates this endocytic pathway by dephosphorylating plasma membrane PI(4,5)P2.

We also investigated the role of Arf6a activity in the nrca14 late endosome phenotype. The role of Arf6 in late endosome trafficking is less well characterized; however recent studies have linked the actions of Arf6 to sorting[51] and acidification[59] at late endosomes. We found that only the Q67L mutation had any effect on late endosomes. Expression of Arf6a Q67L in nrca14 cones rescued the accumulation of Rab7 positive late endosomes at synaptic terminals. Interestingly, this mutation had the opposite effect in WT cells and resulted in a significant increase in the number of Rab7 positive structures at WT cone synapses. The observation the DN Arf6 constructs rescued the autophagosome, but not the late endosome, phenotype in nrca14 cones supports the idea that the accumulation of autophagosomes is not directly caused by defects in late endosome function. This observation along with the increased number of PI(3)P structures in nrca14 cones strongly suggest that there is an increase in the formation of autophagosomes in the absence of SynJ1. Definitive proof of this awaits the development of reagents that recognize pre-autophagosomal structures in zebrafish [60].

The role of SynJ1 in the proper regulation of late endosome dynamics is less clear. Our SynJ1 rescue experiments indicate that the 5’ phosphatase activity of SynJ1, and therefore a PIP with a D-5 phosphate, is involved this process. However, we found that modulating activity of Arf6a did not have the same effects on the late endosome phenotype as the autophagy phenotype suggesting that plasma membrane PI(4,5)P2 levels are not regulating these two processes in the same manner. It is also possible that the late endosome phenotype is less sensitive to alterations in Arf6a activity, and significant changes could not be detected using our methods. In either case, the origin of the abnormal Rab7 structures is unknown, and could arise from dysfunction in either the proper formation, fusion, maturation, or turnover of late endosomes. PI(4,5)P2 has been demonstrated to positively regulate homotypic vacuole fusion in yeast[61], suggesting that an increase in PI(5,4)P2 caused by SynJ1 deficiency could cause the enlarged structures we observe in nrca14 cones. Further work will be required to dissect the role of SynJ1 in late endosome dynamics.

Together we present a model in which SynJ1 negatively regulates the formation of autophagosomes by decreasing plasma membrane PI(4,5)P2. Our study has defined a novel role for SynJ1 in a degradative pathway in cone photoreceptors, and provides a framework for understanding the contribution of SynJ1 to neurodegenerative disease pathology.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The protocol, 3113-01, was approved by IACUC of the University of Washington.

Cloning and plasmids

The tandem mCherry-GFP-LC3 clone was created by inserting mCherry with a C-terminal linker and EcoRI cut site into a pDONR221 vector. GFP-tagged zebrafish LC3 [62] was then amplified with an N-terminal EcoRI site and inserted into the pME mCherry vector. The PLCδ pleckstrin homology domain was purchased from Addgene (plasmid #21262). The PLCδ PH and FAPP1 PH (Tim Levine, [39]) were PCR amplified and inserted into Gateway pDONRP2R-P3 vectors using standard Gateway cloning protocols (Invitrogen). The PI(3)P probe 2XFYVE has previously been characterized [7]. The YFP-2XFYVE (Harold Stenmark) clone was created by inserting YFP with a C-terminal linker and EcoRI cut site into a pDONR221 vector. 2XFYVE was then amplified with an N-terminal EcoRI site and inserted into the pME YFP vector. The mCherry-ML1NX2 (Haoxing Xu) clone has been previously characterized [31], and was inserted into a pDONR221 vector. The full length zebrafish synJ1 gene cDNA has previously been cloned by our lab [17]. An N-terminal FLAG tag was added using overhang PCR methods and the full length clone FLAG-tagged clone was inserted into a pCR8/GW Gateway vector (Invitrogen). The C385S and D732A mutations were created using standard site-directed mutagenesis (primer sequences in Table S1). Full length zebrafish arf6a was cloned from larval zebrafish cDNA. Constitutively active and dominant negative mutations were created using standard site-directed mutagenesis (primer sequences in Table S1). Expression constructs and other fluorescent protein fusions were generated using the MultiSite Gateway System (Invitrogen) and the Tol2 kit. Expression was driven by the cone transducin alpha promoter (TαCP) [63] or the cone-rod homeobox promoter (crx) [64].

Fish husbandry and generation of transgenic zebrafish

Zebrafish were reared and maintained in the University of Washington fish facility as previously described[65]. Embryos were maintained in embryo media (EM) at 28°C on a 14/10hour light/dark cycle prior to experimentation or rearing in the fish facility. Homozygous nrca14 mutants were identified by the optokinetic response assay (OKR) or by genotyping as previously described [18,66]. Because WT and nrca14 heterozygotes appear indistinguishable in every phenotypic assay we have performed, we refer to all OKR-positive larvae as WT. The Tg(crx:Man2a-GFP), Tg(TαCP:GFP-rab7) and Tg(TαCP:GFP-map1lc3b) fish lines have been previously described [18]. We created other transgenic fish lines as previously described [18,67]. Newly identified transgenic fish were assayed by OKR at 5dpf to ensure that transgene expression did not affect visual responses. List of all transgenic lines used in this study in Table S2.

Immunohistochemistry

All zebrafish larvae were fixed at the indicated developmental stage between 12pm and 1pm to minimize variation caused by circadian effects. Retinal slices were prepared as previously described [68]. To detect FLAG-tagged SJCs, slices were incubated with 1:1000 anti-FLAG M2 (Sigma) primary antibody at 4°C overnight followed by secondary anti-mouse Alexa 568 (Invitrogen, A11002) at 1:200 for 1 hour at room temperature. Nuclei were counter stained with 5μM Hoechst (Invitrogen). Slides were mounted with a coverslip and Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotech). Imaging of retinal sections was performed on an Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope with a 60X 1.35NA oil immersion objective. Fluoview software (Olympus version 2.0c) was used to acquire images.

Live Imaging

Larvae were treated with 0.003% 1-phenyl-2-thiourea (PTU) in EM at ~24 hours post fertilization (hpf) to prevent melanization. Larvae were anaesthetized in Tricaine (Sigma) and mounted in warm 0.5–1% low mount agarose. Embedded larvae were covered in EM containing PTU and Tricaine and imaged. Imaging was performed on an Olympus FV1000 at room temperature using a 40X 0.8NA water immersion objective. Fluoview software (Olympus version 2.0c) was used to acquire images.

Transmission electron microscopy

Transmission electron microscopy was performed at the UW Vision Core as previously described [26]. For quantification, the entire retina was imaged.

Image processing and data analysis

Images were processed using NIH ImageJ (v1.49). Representative images in Figures are 2μm MAX projections of confocal stacks (Figures 1,–3, 4A, 5A, 7–9), average projections of a single cell (Figure 6), or single optical slices (Figures 4B, 5B). Contrast was adjusted and a 1 pixel median filter was applied to representative images in ImageJ, any adjustments were applied to in the exact same manner to WT and nrca14 images. All puncta scoring was performed using blind manual counting on individual slices of unprocessed z-stacks. For qualitative comparisons between WT and nrca14 larvae, at least 6 larvae of each genotype were analyzed. For quantitative data, the number of larvae analyzed is included in the text and Figure legends. R (v3.0.1) was used for statistical analysis. Error bar values and statistical tests are described in Figure legends.

Analysis of LC3 vesicle dynamics

Images were acquired in 5 second intervals for 10 minutes. Timelapses were analyzed using the SpotTracker2D plugin in ImageJ [69]. Images were processed using the StackReg [70] and SpotEnhancing Filter2D plugins. Images were assigned random numbers prior to tracking. Particles were chosen randomly in the first frame and tracked until the particle disappeared, or the timelapse ended. Particles that did not persist for at least 12 frames (1 minute) were discarded. A pause was defined as a movement of less than 0.475μm between frames (0.095μm/s).

Colocalization analysis

Background correction was performed using a modified flat-field correction method[71]. After correction, images from each channel were thresholded and converted to a binary image using an automated method to avoid user bias. Using the Calculator Plus plugin we created binary images that represent overlap from the two channels, and quantified the number of voxels in each image. We express colocalization as percent colocalization. Figure 4E shows the percent colocalization of the indicated marker with 2XFYVE defined as [number of voxels positive for both the marker and 2XFYVE/the number of voxels positive for the marker] × 100%. Figure 4F shows the percent colocalization of the indicated marker with 2XFYVE defined as [number of voxels positive for both the marker and 2XFYVE/the number of voxels positive for 2XFYVE] × 100%.

Supplementary Material

Synopsis.

The phosphoinositide phosphatase, Synaptojanin 1 (SynJ1) is linked to neurodegenerative diseases that have dysfunctional protein degradation. We examined in vivo the role of SynJ1 in protein degradation pathways in cone photoreceptors and found that the 5’ phosphatase, but not Sac1, domain of SynJ1 regulates autophagosome and late endosome function. Altered Arf6 activity rescues autophagy defects in the absence of SynJ1. We defined a link between SynJ1 and protein degradation that advances our understanding of SynJ1, Arf6, and PI(4,5)P2 in neuronal function.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jing Huang and Ed Parker at the UW Vision core for help with preparing retinal slices and electron microscopy respectively. We thank Harold Stenmark (Oslo University Hospital), Haoxing Xu (University of Michigan) and Tim Levine (University College London) for contributing plasmids. We thank Neil Wilson (University of Washington) for assistance with Gateway cloning and Daryl Phuong and Van Tran (University of Washington) for assistance with genotyping and fish screening. This work is supported by NIH grant EY015165 (SEB), and NEI grant EY001730, which supports the UW Vision Core. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CA

constitutively active

- crx

cone-rod homeobox

- DN

dominant negative

- dpf

days post fertilization

- FAPP1

Four-phosphate-adaptor protein 1

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- hpf

hours post fertilization

- IS

inner segment

- LC3

Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3

- Man2a

mannosidase2a

- nrca14

no optokinetic response c

- OKR

Optokinetic response

- OS

outer segment

- PH

pleckstrin homology

- PI

phosphatidylinositol

- PI(x)Py

phosphatidylinositol x-yphosphate

- PLCδ

Phospholipase C delta

- PLD

Phospholipase D

- PTU

1-phenyl-2-thiourea

- SJC

Synaptojanin1 construct

- SynJ1

Synaptojanin1

- Tg

transgenic

- TαCP

cone transducin alpha promoter

- YFP

yellow fluorescent protein

- zf

zebrafish

References

- 1.Fecto F, Esengul YT, Siddique T. Protein recycling pathways in neurodegenerative diseases. Alzheimer’s research & therapy. 2014;6:13. doi: 10.1186/alzrt243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartong DT, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet. 2006;368:1795–809. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69740-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldberg AL. Protein degradation and protection against misfolded or damaged proteins. Nature. 2003;426:895–9. doi: 10.1038/nature02263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klionsky DJ. Autophagy: from phenomenology to molecular understanding in less than a decade. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2007;8:931–7. doi: 10.1038/nrm2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huotari J, Helenius A. Endosome maturation. The EMBO journal. 2011;30:3481–500. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho CY, Alghamdi TA, Botelho RJ. Phosphatidylinositol-3,5-bisphosphate: no longer the poor PIP2. Traffic. 2012;13:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gillooly DJ, Morrow IC, Lindsay M, Gould R, Bryant NJ, et al. Localization of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate in yeast and mammalian cells. The EMBO journal. 2000;19:4577–88. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.17.4577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong XP, Shen D, Wang X, Dawson T, Li X, et al. PI(3,5)P(2) controls membrane trafficking by direct activation of mucolipin Ca(2+) release channels in the endolysosome. Nat Commun. 2010;1:38. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dall’Armi C, Devereaux KA, Di Paolo G. The role of lipids in the control of autophagy. Current biology: CB. 2013;23:R33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Billcliff PG, Lowe M. Inositol lipid phosphatases in membrane trafficking and human disease. The Biochemical journal. 2014;461:159–75. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moreau K, Ravikumar B, Puri C, Rubinsztein DC. Arf6 promotes autophagosome formation via effects on phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and phospholipase D. J Cell Biol. 2012;196:483–96. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201110114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rong Y, Liu M, Ma L, Du W, Zhang H, et al. Clathrin and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate regulate autophagic lysosome reformation. Nature cell biology. 2012;14:924–34. doi: 10.1038/ncb2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Honda A, Nogami M, Yokozeki T, Yamazaki M, Nakamura H, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase alpha is a downstream effector of the small G protein ARF6 in membrane ruffle formation. Cell. 1999;99:521–32. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81540-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jovanovic OA, Brown FD, Donaldson JG. An effector domain mutant of Arf6 implicates phospholipase D in endosomal membrane recycling. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:327–35. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-06-0523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown FD, Rozelle AL, Yin HL, Balla T, Donaldson JG. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and Arf6-regulated membrane traffic. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:1007–17. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cremona O, Di Paolo G, Wenk MR, Luthi A, Kim WT, et al. Essential role of phosphoinositide metabolism in synaptic vesicle recycling. Cell. 1999;99:179–88. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holzhausen LC, Lewis AA, Cheong KK, Brockerhoff SE. Differential role for synaptojanin 1 in rod and cone photoreceptors. J Comp Neurol. 2009;517:633–44. doi: 10.1002/cne.22176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.George AA, Hayden S, Holzhausen LC, Ma EY, Suzuki SC, et al. Synaptojanin 1 is required for endolysosomal trafficking of synaptic proteins in cone photoreceptor inner segments. PLoS One. 2014;9:e84394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berman DE, Dall’Armi C, Voronov SV, McIntire LB, Zhang H, et al. Oligomeric amyloid-beta peptide disrupts phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate metabolism. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:547–54. doi: 10.1038/nn.2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krebs CE, Karkheiran S, Powell JC, Cao M, Makarov V, et al. The Sac1 domain of SYNJ1 identified mutated in a family with early-onset progressive Parkinsonism with generalized seizures. Human mutation. 2013;34:1200–7. doi: 10.1002/humu.22372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quadri M, Fang M, Picillo M, Olgiati S, Breedveld GJ, et al. Mutation in the SYNJ1 gene associated with autosomal recessive, early-onset Parkinsonism. Human mutation. 2013;34:1208–15. doi: 10.1002/humu.22373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu L, Zhong M, Zhao J, Rhee H, Caesar I, et al. Reduction of synaptojanin 1 accelerates Abeta clearance and attenuates cognitive deterioration in an Alzheimer mouse model. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:32050–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.504365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allwardt BA, Lall AB, Brockerhoff SE, Dowling JE. Synapse formation is arrested in retinal photoreceptors of the zebrafish nrc mutant. J Neurosci United States. 2001:2330–42. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-07-02330.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Epps HA, Yim CM, Hurley JB, Brockerhoff SE. Investigations of photoreceptor synaptic transmission and light adaptation in the zebrafish visual mutant nrc. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:868–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Epps HA, Hayashi M, Lucast L, Stearns GW, Hurley JB, et al. The zebrafish nrc mutant reveals a role for the polyphosphoinositide phosphatase synaptojanin 1 in cone photoreceptor ribbon anchoring. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8641–50. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2892-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmitt EA, Dowling JE. Early retinal development in the zebrafish, Danio rerio: light and electron microscopic analyses. J Comp Neurol. 1999;404:515–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rowland AM, Richmond JE, Olsen JG, Hall DH, Bamber BA. Presynaptic terminals independently regulate synaptic clustering and autophagy of GABAA receptors in Caenorhabditis elegans. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2006;26:1711–20. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2279-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen W, Ganetzky B. Autophagy promotes synapse development in Drosophila. The Journal of cell biology. 2009;187:71–9. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200907109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stearns G, Evangelista M, Fadool JM, Brockerhoff SE. A mutation in the cone-specific pde6 gene causes rapid cone photoreceptor degeneration in zebrafish. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13866–74. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3136-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kimura S, Noda T, Yoshimori T. Dissection of the autophagosome maturation process by a novel reporter protein, tandem fluorescent-tagged LC3. Autophagy. 2007;3:452–60. doi: 10.4161/auto.4451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X, Wang X, Zhang X, Zhao M, Tsang WL, et al. Genetically encoded fluorescent probe to visualize intracellular phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate localization and dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:21165–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311864110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindmo K, Stenmark H. Regulation of membrane traffic by phosphoinositide 3-kinases. Journal of cell science. 2006;119:605–14. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ktistakis NT, Karanasios E, Manifava M. Dynamics of autophagosome formation: a pulse and a sequence of waves. Biochem Soc Trans. 2014;42:1389–95. doi: 10.1042/BST20140183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Juhasz G, Hill JH, Yan Y, Sass M, Baehrecke EH, et al. The class III PI(3)K Vps34 promotes autophagy and endocytosis but not TOR signaling in Drosophila. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:655–66. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Molejon MI, Ropolo A, Re AL, Boggio V, Vaccaro MI. The VMP1-Beclin 1 interaction regulates autophagy induction. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1055. doi: 10.1038/srep01055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stein MP, Feng Y, Cooper KL, Welford AM, Wandinger-Ness A. Human VPS34 and p150 are Rab7 interacting partners. Traffic. 2003;4:754–71. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vicinanza M, Korolchuk VI, Ashkenazi A, Puri C, Menzies FM, et al. PI(5)P Regulates Autophagosome Biogenesis. Mol Cell. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balla T, Varnai P. Visualizing cellular phosphoinositide pools with GFP-fused protein-modules. Sci STKE. 2002;2002:pl3. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.125.pl3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levine TP, Munro S. Targeting of Golgi-specific pleckstrin homology domains involves both PtdIns 4-kinase-dependent and -independent components. Curr Biol. 2002;12:695–704. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00779-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Matteis MA, Di Campli A, Godi A. The role of the phosphoinositides at the Golgi complex. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1744:396–405. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo S, Stolz LE, Lemrow SM, York JD. SAC1-like domains of yeast SAC1, INP52, and INP53 and of human synaptojanin encode polyphosphoinositide phosphatases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12990–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.12990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stuart GW, McMurray JV, Westerfield M. Replication, integration and stable germ-line transmission of foreign sequences injected into early zebrafish embryos. Development (Cambridge, England) 1988;103:403–12. doi: 10.1242/dev.103.2.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hughes WE, Cooke FT, Parker PJ. Sac phosphatase domain proteins. The Biochemical journal. 2000;350(Pt 2):337–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stefan CJ, Audhya A, Emr SD. The yeast synaptojanin-like proteins control the cellular distribution of phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate. Molecular biology of the cell. 2002;13:542–57. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-10-0476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mani M, Lee SY, Lucast L, Cremona O, Di Paolo G, et al. The dual phosphatase activity of synaptojanin1 is required for both efficient synaptic vesicle endocytosis and reavailability at nerve terminals. Neuron. 2007;56:1004–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jefferson AB, Majerus PW. Mutation of the conserved domains of two inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatases. Biochemistry. 1996;35:7890–4. doi: 10.1021/bi9602627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whisstock JC, Romero S, Gurung R, Nandurkar H, Ooms LM, et al. The inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatases and the apurinic/apyrimidinic base excision repair endonucleases share a common mechanism for catalysis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37055–61. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006244200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dong Y, Gou Y, Li Y, Liu Y, Bai J. Synaptojanin cooperates in vivo with endophilin through an unexpected mechanism. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.05660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.D’Souza-Schorey C, van Donselaar E, Hsu VW, Yang C, Stahl PD, et al. ARF6 targets recycling vesicles to the plasma membrane: insights from an ultrastructural investigation. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:603–16. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.3.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Macia E, Luton F, Partisani M, Cherfils J, Chardin P, et al. The GDP-bound form of Arf6 is located at the plasma membrane. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2389–98. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ghossoub R, Lembo F, Rubio A, Gaillard CB, Bouchet J, et al. Syntenin-ALIX exosome biogenesis and budding into multivesicular bodies are controlled by ARF6 and PLD2. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3477. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Naslavsky N, Weigert R, Donaldson JG. Convergence of non-clathrin- and clathrin-derived endosomes involves Arf6 inactivation and changes in phosphoinositides. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:417–31. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-04-0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gong LW, De Camilli P. Regulation of postsynaptic AMPA responses by synaptojanin 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:17561–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809221105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dyment DA, Smith AC, Humphreys P, Schwartzentruber J, Beaulieu CL, et al. Homozygous nonsense mutation in SYNJ1 associated with intractable epilepsy and tau pathology. Neurobiol Aging. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McIntire LB, Berman DE, Myaeng J, Staniszewski A, Arancio O, et al. Reduction of synaptojanin 1 ameliorates synaptic and behavioral impairments in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2012;32:15271–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2034-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ravikumar B, Moreau K, Jahreiss L, Puri C, Rubinsztein DC. Plasma membrane contributes to the formation of pre-autophagosomal structures. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:747–57. doi: 10.1038/ncb2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aikawa Y, Martin TF. ARF6 regulates a plasma membrane pool of phosphatidylinositol(4,5)bisphosphate required for regulated exocytosis. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:647–59. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boucrot E, Ferreira AP, Almeida-Souza L, Debard S, Vallis Y, et al. Endophilin marks and controls a clathrin-independent endocytic pathway. Nature. 2015;517:460–5. doi: 10.1038/nature14067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hurtado-Lorenzo A, Skinner M, El Annan J, Futai M, Sun-Wada GH, et al. V-ATPase interacts with ARNO and Arf6 in early endosomes and regulates the protein degradative pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:124–36. doi: 10.1038/ncb1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Varga M, Fodor E, Vellai T. Autophagy in zebrafish. Methods. 2015;75:172–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mayer A, Scheglmann D, Dove S, Glatz A, Wickner W, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate regulates two steps of homotypic vacuole fusion. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:807–17. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.3.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.He C, Bartholomew CR, Zhou W, Klionsky DJ. Assaying autophagic activity in transgenic GFP-Lc3 and GFP-Gabarap zebrafish embryos. Autophagy. 2009;5:520–6. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.4.7768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kennedy BN, Alvarez Y, Brockerhoff SE, Stearns GW, Sapetto-Rebow B, et al. Identification of a zebrafish cone photoreceptor-specific promoter and genetic rescue of achromatopsia in the nof mutant. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:522–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Suzuki SC, Bleckert A, Williams PR, Takechi M, Kawamura S, et al. Cone photoreceptor types in zebrafish are generated by symmetric terminal divisions of dedicated precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303551110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Westerfield M. The Zebrafish Book: A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Brachydanio rerio) Eugene: University of Oregon Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brockerhoff SE. Measuring the optokinetic response of zebrafish larvae. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2448–51. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kikuta H, Kawakami K. Transient and stable transgenesis using tol2 transposon vectors. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;546:69–84. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-977-2_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brockerhoff SE, Hurley JB, Niemi GA, Dowling JE. A new form of inherited red-blindness identified in zebrafish. J Neurosci. 1997;20:1–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04236.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sage D, Neumann FR, Hediger F, Gasser SM, Unser M. Automatic tracking of individual fluorescence particles: application to the study of chromosome dynamics. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2005;14:1372–83. doi: 10.1109/tip.2005.852787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thevenaz P, Ruttimann UE, Unser M. A pyramid approach to subpixel registration based on intensity. IEEE Trans Image Process. 1998;7:27–41. doi: 10.1109/83.650848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leong FJ, Brady M, McGee JO. Correction of uneven illumination (vignetting) in digital microscopy images. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:619–21. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.8.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Donaldson JG. Phospholipase D in endocytosis and endosomal recycling pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791:845–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dall’Armi C, Hurtado-Lorenzo A, Tian H, Morel E, Nezu A, et al. The phospholipase D1 pathway modulates macroautophagy. Nat Commun. 2010;1:142. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.