Abstract

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death for Americans. As coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) remains a mainstay of therapy for CVD and native vein grafts are limited by issues of supply and lifespan, an effective readily available tissue-engineered vascular graft (TEVG) for use in CABG would provide drastic improvements in patient care. Biomechanical mismatch between vascular grafts and native vasculature has been shown to be the major cause of graft failure, and therefore, there is need for compliance-matched biocompatible TEVGs for clinical implantation. The current study investigates the biaxial mechanical characterization of acellular electrospun glutaraldehyde (GLUT) vapor-crosslinked gelatin/fibrinogen cylindrical constructs, using a custom-made microbiaxial optomechanical device (MOD). Constructs crosslinked for 2, 8, and 24 hrs are compared to mechanically characterized porcine left anterior descending coronary (LADC) artery. The mechanical response data were used for constitutive modeling using a modified Fung strain energy equation. The results showed that constructs crosslinked for 2 and 8 hrs exhibited circumferential and axial tangential moduli (ATM) similar to that of the LADC. Furthermore, the 8-hrs experimental group was the only one to compliance-match the LADC, with compliance values of 0.0006±0.00018 mm Hg−1 and 0.00071±0.00027 mm Hg−1, respectively. The results of this study show the feasibility of meeting mechanical specifications expected of native arteries through manipulating GLUT vapor crosslinking time. The comprehensive mechanical characterization of cylindrical biopolymer constructs in this study is an important first step to successfully develop a biopolymer compliance-matched TEVG.

Introduction

CVD continues to be the major cause of death in the U.S. [1]. In 2010, CVD accounted for 787,650 of all 2,468,435 deaths in the U.S., approximately 1 out of every 3 Americans [1]. The highest percentage of CVD-related deaths were attributed to coronary artery disease. About 158,000 CABG procedures were performed in 2010 [1]. There is an increasing demand for affordable, biocompatible, and more easily accessible coronary vascular grafts. Biological grafts, such as saphenous veins grafts and autologous native vessels, have been the gold standards for CABGs for many years. Unfortunately, these biological grafts are limited by issues related to availability and shorter durability due to calcification [2]. Additionally, inherent compliance mismatch between the native vessel and graft can lead to graft failure via intimal hyperplasia [3,4].

TEVGs offer an alternative source for grafts which may be engineered to be nonthrombogenic, biocompatible, nonimmunogenic, resistant to infection, mechanically stable, and compliance-matched to the native vessel. Electrospinning is a popular method to produce nonwoven fibrous scaffolds for cell culture and has been used extensively to create cylindrical constructs implemented to develop TEVGs. Synthetic polymers have been used by many researchers to fabricate electrospun scaffolds [5–9]. Some researchers have mixed native nonsynthetic biopolymers into their synthetic material composition to more closely resemble the microstructure of vasculature [10–14]. Small-diameter synthetic polymer grafts, which introduce an exogenous nonbiological material into the body, have been shown to be biocompatible and/or biodegradable in some small animal models [15–20] but may not be suitable for some large animal models [21,22] and clinical patients [3,23,24], due to acute thrombogenicity and anastomotic intimal hyperplasia. While some researchers have attempted to address this issue by reducing the thrombogenetic nature of the synthetic polymer [8,25], others have considered nonsynthetic biopolymers to fabricate their scaffolds [26–32].

Coronary arteries are primarily composed of an extracellular matrix of collagen and elastin. Some researchers have suggested developing electrospun scaffolds composed of collagen, elastin, and other synthetic polymers to provide mechanical support, in an effort to match the structural, mechanical, and geometric properties of native coronary arteries [33–35]. However, electrospinning collagen and elastin into constructs does not provide the necessary mechanical integrity [36]; therefore, some have resorted to utilizing crosslinking methods to alter the mechanical properties of the biopolymer scaffold [33,37,38].

Gelatin is a structurally similar derivative of collagen acquired by denaturing the triple-helix structure of collagen. Gelatin has been found to be a cost-effective biodegradable biopolymer [39] with more availability of arginylglycylaspartic acid sequence cell binding sites compared to collagen [40]. Additionally, relative to collagen, gelatin has been reported to reduce the potential of an antigenic response in vivo [41]. The nonantigenicity of gelatin has been attributed to the absence of aromatic groups. Specifically, gelatin is deficient in both tyrosine and tryptophan and contains only low levels of phenylalanine [41,42]. Researchers have electrospun gelatin/fibrinogen sheets and successfully cultured human cardiomyocytes with brief mechanical characterization [43]. Along those lines, our group investigated the feasibility of growing porcine vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) on electrospun gelatin/fibrinogen scaffolds [44]. Our results showed that SMCs proliferated and migrated within the scaffold. In addition, transforming growth factor beta 2 (TGFβ2) was shown to have a significant effect on the proliferation and collagen deposition of the SMCs, which suggests that seeded SMCs could have the ability to modify the mechanical properties of the scaffold over time by manipulating the biochemical environment.

There are many factors that may lead to vascular graft failure including biological factors, vascular injury, hemodynamic factors, compliance mismatch, and other differences in mechanical properties between graft and native vessel [45]. Many biomechanical researchers have acknowledged the importance of evaluating graft compliance, burst pressure, and suture retention in the development of TEVGs [20,46–49]. Compliance mismatch is one of the major causes of restenosis and graft failure due to perturbations in local hemodynamics [50]. Therefore, it is crucial that the mechanical properties of the TEVG be comparable to that of native vessels. For the purposes of this manuscript, we sought to develop an acellular graft whose mechanical properties can be modulated to be compliance-matched. These grafts can be used as acellular small-diameter vascular grafts (in vivo rat studies currently ongoing in our laboratory) or as a means to grow a functional TEVG in an ex vivo flow/stretch bioreactor that will be later implanted. In the latter context, the goal of creating an acellular compliance-matched TEVG in this work is to create a graft that will encourage cell-mediated extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition and remodeling as our constructs are grown in a flow/stretch bioreactor. Our hypothesis for this study was that varying the degree of crosslinking of electrospun gelatin/fibrinogen tubular constructs would yield TEVGs with mechanical properties similar to native vessels. As such, in this study we investigated the feasibility of developing an acellular gelatin/fibrinogen TEVG that could compliance-match with porcine LADC artery via examination of the effects of crosslinking time, axial load, and intraluminal pressure on the mechanical properties and performing a comprehensive tubular biaxial mechanical analysis of the constructs under normal physiological conditions.

Materials

Porcine Coronary Artery Data.

Our research group has previously collected mechanical data from porcine LADC extracted from hearts obtained from the University of Arizona Meat Sciences Laboratory [51]. Biaxial stress–strain mechanical data were determined for the proximal, middle, and distal sections of the coronary arteries. Datasets also included artery outer diameter and thickness. For this study, the LADC distal section dataset (n = 3) was chosen exclusively as the gold standard dataset to compare to our TEVGs.

Fabricating Electrospun Constructs.

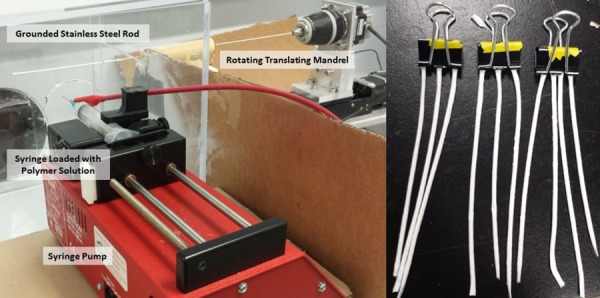

A custom-made electrospinning apparatus was used to fabricate the tubular constructs. Gelatin extracted from porcine skin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and fraction I bovine fibrinogen (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFP) (Sigma-Aldrich) at a 80:20 ratio to create a 10% (w/v) solution. Constructs with this composition have been shown by our group to promote cell adherence and proliferation compared to alternative ratios [44]. In a ventilation hood, the solution was loaded into a 5 ml BD syringe with a 23 gauge stainless steel dispensing needle and attached to a NE-100 single syringe pump (New Era Pump Systems, Farmingdale, NY). A voltage difference of 15 kV was generated between the dispensing tip and a grounded rotating translating stainless steel mandrel (1.4 mm OD) at a rotational speed of 25 rpm and a translational speed of 10 mm/s. The syringe tip and the rotating translating rod were enclosed in an acrylic housing for additional insulation and control. The internal environment's temperature and relative humidity remained constant at about 25 ± 2.0 °C and 38 ± 3%, respectively. The complete electrospinning setup and fabricated noncrosslinked electrospun constructs are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

(Left) Electrospinning setup which includes a syringe pump setup with a syringe loaded with the gelatin/fibrinogen solution. The rotating translating mandrel is enclosed in an acrylic housing. (Right) Electrospun constructs after being removed from mandrel before being placed in the cross-linking chamber.

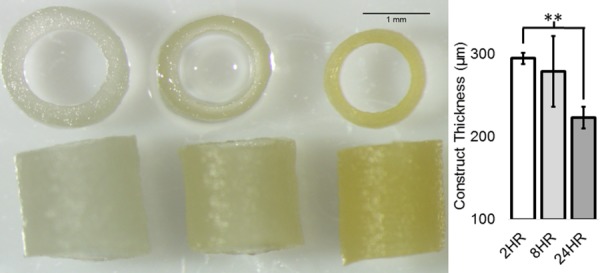

For each construct, the loaded syringe dispensed 0.35 ml of the biopolymer solution at a rate of 30 μl/min. The high-voltage difference created a driving force that pulled the polymer from the solution forming fibers, which were deposited onto the grounded rotating translating mandrel. After electrospinning, the newly created fibrous constructs were removed carefully from the mandrel. The constructs were then placed into a desiccant chamber containing 25% (v/v) liquid GLUT at the bottom of the chamber for crosslinking. The constructs were suspended inside the chamber and exposed to the GLUT vapor phase for 2, 8, and 24 hrs. After crosslinking, the constructs were suspended in a convection oven at 42 °C for 24 hrs before they were placed in deionized water for another 24 hrs to maximize the GLUT removal from the constructs. Before mechanical testing, the constructs were placed in Nerl blood bank saline (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) for conditioning. Representative cross-sectional and en face views of constructs from each cross-linking time experimental group were imaged using a dissecting microscope and are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

(Left) Representative construct images. (Right) Average thickness of 2, 8, and24 hrs crosslinked constructs with error bars indicating standard deviation. Double asterisks indicate p value < 0.01 (n = 3).

Methods

Biaxial Mechanical Testing

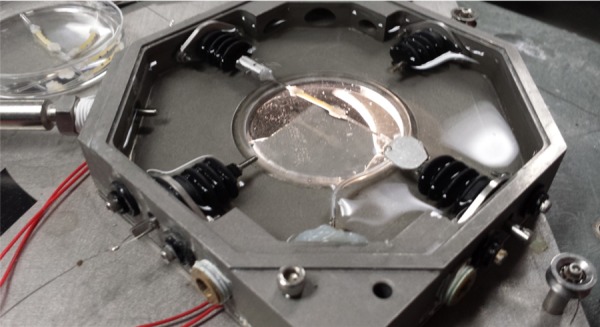

Microbiaxial Optomechanical Device.

A custom-made MOD, shown in Fig. 3, has been used by our research group to conduct extensive studies on the mechanical behavior of porcine and mouse arteries [51–56]. This device has the capability of stretching the tubular samples axially, while recording axial load, pressure, and circumferential/axial strain information simultaneously. Similar to the methods that have been described in the literature published by our research group [51], the mechanical properties of the tubular constructs were assessed both circumferentially and axially. Briefly, each construct was cannulated on both ends with glass capillary tubes and attached to the MOD system to be intraluminally pressurized in a bath, filled with Nerl™ blood bank saline (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) kept at 37 °C. Each construct was preconditioned axially to at least 20% strain at 0.01 mm/s several times. The constructs were also preconditioned circumferentially by applying an intraluminal pressure from 0 mm Hg to 120 mm Hg at a rate of approximately 1 mm Hg/s seven times. After preconditioning, a standard preload of 3.5±0.4 g was applied to the construct to allow it to be taut before testing. According to previous studies by our laboratory group, the in situ axial loads for LADCs were found to be around 30 g at an axial strain of 34±6% [51]. Therefore, for circumferential testing, each construct was axially stretched at a rate of 0.01 mm/s to axial loads of 0 g, 10 g, and 30 g at 0 mm Hg, which correspond to 0%, 33%, and 100% of LADC in situ axial loads, respectively. At each axial load, the constructs were pressurized from 0 mm Hg to 120 mm Hg and then back down to 0 mm Hg at a rate of approximately 1 mm Hg/s. For axial testing, the pressure was kept constant at 0, 70, and 120 mm Hg and the constructs were stretched axially to about 20% axial strain at a rate of 0.01 mm/s. For both these tests, the axial load and the intraluminal pressure were monitored and recorded. Furthermore, the outer radius and axial strain were tracked using image processing software integrated into the MOD. This software tracked the outer radius and the local axial Green strain during biaxial mechanical testing, based off real-time marker tracking of two small cyanoacrylate/ceramic powder markers placed on the constructs.

Fig. 3.

Gelatin/fibrinogen tubular construct loaded into the MOD

Constitutive Modeling.

Equation (1) was used to calculate the circumferential Green strain, which assumes no shear in the sample:

| (1) |

where Eθθ and are the circumferential Green strain and the circumferential stretch ratio (unitless), respectively. is defined as , where is the deformed outer radius (m) and is the undeformed outer radius (m). Similarly, axial circumferential Green strain was determined by using the following equation:

| (2) |

where is the axial Green strain and is the axial stretch ratio (unitless). is defined as , where and are the deformed distance (m) and the undeformed distance (m) between the markers parallel to the construct longitudinal axis, respectively. The axial Cauchy stress was determined using the following equation:

| (3) |

where , , and are the Cauchy stress (Pa), the axial load (N), and the deformed cross-sectional area (m2), respectively. Assuming incompressibility (constant volume), the deformed and undeformed cross-sectional areas were related using the following equation:

| (4) |

where is the construct undeformed cross-sectional area. The hoop stress at the midpoint of the construct/LADC thickness was calculated using a thick-wall assumption by using the following equation [57]:

| (5) |

where is the hoop stress (Pa), is the intraluminal pressure (Pa), is the outer radius of the construct (m), and is the inner radius (m). Equation (5) determines hoop stress at the midpoint between and , which was assumed to be the representative hoop stress of the construct throughout the construct thickness. The circumferential and axial second Piola–Kirchhoff stresses, and , respectively, were calculated using Eqs. (6) and (7), respectively, assuming no shear stresses:

| (6) |

| (7) |

The stress–strain data were fit to the following modified Fung stain-energy constitutive equation [51]:

| (8) |

where , is the strain energy density, and (kPa), , , and are the material constants. Coefficients of determination (R2) and qualitative visual assessment were used to evaluate the accuracy of the fit.

Generation of Averaged Stress–Strain Plots.

For each construct replicate from each experimental group, the axial and circumferential second Piola–Kirchhoff stresses were plotted against the circumferential and axial Green strain, respectively. In order to average the mechanical data for all the replicates for each experimental group, the data from each replicate were fit to a third-order single variable polynomial equation. R2 values and visual assessment were used to evaluate the accuracy of the fit. The resulting fitted polynomial curve for each replicate was averaged within the same experimental group in strain ranges that overlapped between the replicates. These plots were generated for all experimental groups, including the LADC data.

Tangential Moduli and Statistics.

The circumferential tangential moduli (CTM) and the ATM were extracted from each stress–strain curve by calculating the slopes of the fitted polynomial curve for each test replicate. All ATM and CTM values were averaged for the same experimental group. The CTM were determined at pressures of 0, 70, and 120 mm Hg for the circumferential stress–strain curves at axial loads of 0, 10, and 30 g. The ATM were determined at axial Green strains of 0, 0.05, 0.1, and 0.15 for the axial stress–strain plots at 0, 70, and 120 mm Hg. These values were plotted against the equivalent values for the LADC comparison. To determine statistical significance, a two-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to determine the effect(s), if any, of axial load and cross-linking time on the CTM. In addition, a two-factor ANOVA was performed to determine the effect(s), if any, of intraluminal pressure and cross-linking time on the ATM. To determine the statistically significant factors, individual two-sample two-tailed t tests were conducted post-hoc comparing the circumferential and ATM of each experimental group to that of the LADC. For all statistical tests, a critical p value of 0.05 was used to define significance.

Compliance and Statistics.

To calculate the compliance of each experimental group at each axial load, the below equation was used [9]

| (9) |

where is the diameter of the vessel at 120 mm Hg (m) and is the diameter of the vessel at 70 mm Hg (m). A two-way ANOVA was performed to determine the significance of the effect of axial load and crosslinking time on compliance.

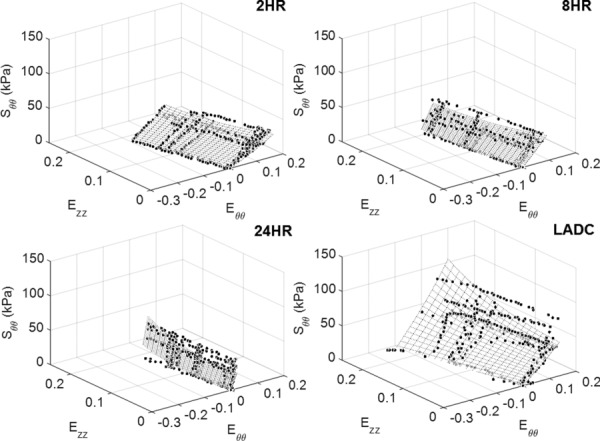

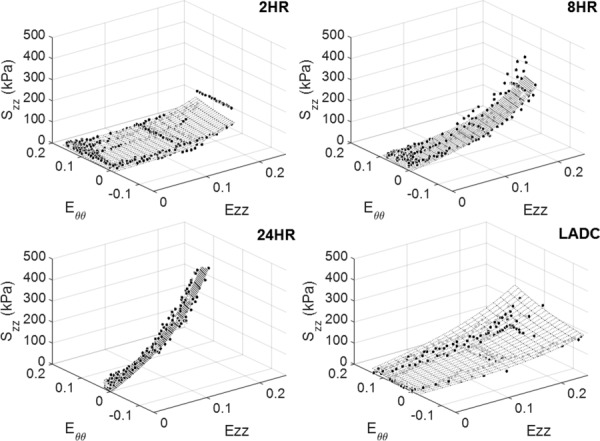

Mechanical Response Surfaces.

For further construct mechanical characterization and visualization, the axial and circumferential second Piola–Kirchhoff stresses of each biaxial mechanical test were plotted against the axial Green strains and the circumferential Green strains in a 3D scatter plot. A surface plot was generated for each replicate by fitting the data generated by the axial and circumferential tests to a multivariable exponential equation. R2 values and visual assessment were used to evaluate the accuracy of the fit. The individual surface plots for each test of the same experimental group were averaged to generate an averaged surface plot. Furthermore, adding and subtracting one standard deviation from the averaged plot was performed to generate upper limit and lower limit surface plots for each experimental group, respectively.

Construct Fiber Orientation

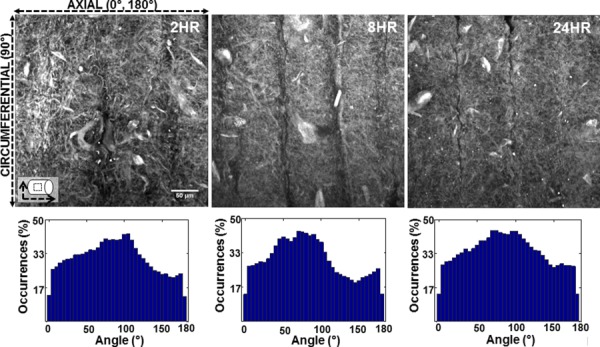

Multiphoton Imaging.

To further characterize the gelatin/fibrinogen constructs and to investigate possible explanations for any mechanical anisotropy, the constructs were imaged using the advanced intravital microscope (AIM) for multiphoton imaging at the University of Arizona's BIO5 Institute [55] at 0 mm Hg intraluminal pressure with no axial stretch. The AIM is a Zeiss LSM 510 NLO upright laser-scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss) coupled to a Mira 900 150-fs pulsed Ti-Sapphire laser (Coherent). An Olympus XLUMPLFL 20 × water immersion objective with a numerical aperture of 0.9 was used to collect the backscattered signal over a 2505 × 2505 μm field of view at 2 μm z-steps, resulting in multiple two-photon images of the fiber autofluorescence imaged to a depth of about 120 μm. This autofluorescent signal was split with a 580 nm dichroic mirror and collected through a 550/88 bandpass filter. All slice images were combined into a maximum intensity projection (MIP). This imaging process was performed for the constructs crosslinked for 2, 8, and 24 hrs. An in-house matlab image processing software (IAGUI) was used to determine fiber orientation data based off the MIP image for each experimental group [52,53]. The software detects fiber orientation and assigns intensity values for each angle value. This resulted in fiber angle histograms that describe the fiber orientation distribution. The plots generated by IAGUI were used to qualitatively determine the effect of crosslinking on fiber orientation.

Results

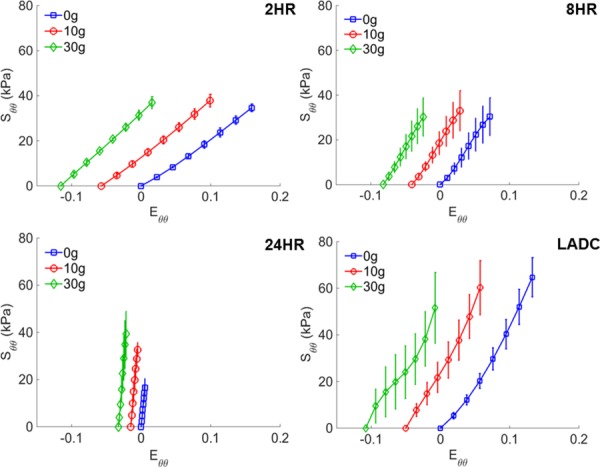

Stress–Strain Curves.

The maximum average circumferential stresses for all axial loads for the 2, 8, and 24 hrs constructs at 120 mm Hg were 37.9±2.8 kPa, 33.0±9.0 kPa, and 39.3±9.6 kPa, respectively, compared to that of the LADC at 64.7±8.4 kPa, nearly double the maximum circumferential stresses of the construct at the same axial loads. The circumferential stress–strain curves, shown in Fig. 4, qualitatively demonstrate that crosslinking time changes the material properties of the constructs, specifically increasing the material stiffness in the circumferential direction. The LADC was the only experimental group that exhibited circumferential strain-stiffening.

Fig. 4.

Averaged circumferential stress–strain curves for gelatin/fibrinogen constructs at 0, 10, and 30 g of axial load for constructs crosslinked for 2, 8, and 24 hrs and for the distal section of LADC. Error bars represent one standard deviation.

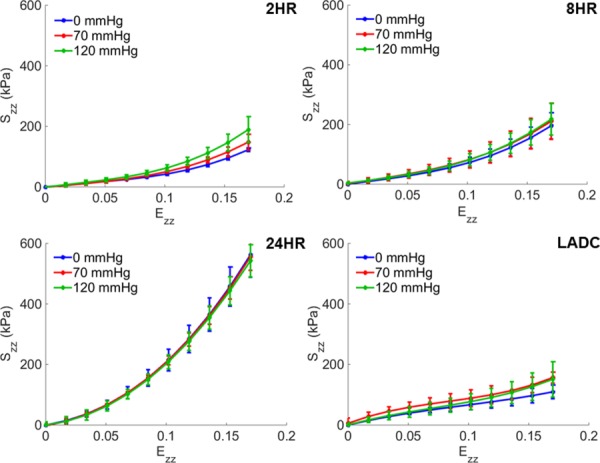

Due to deformability limitations, some 2-hrs constructs snapped at an axial Green strain of about 0.17. Therefore, all experimental groups were plotted up to an axial Green strain of 0.17 for proper comparison. The maximum average axial stresses for the 2, 8, and 24 hrs constructs were 189.4±43.0 kPa, 217.6±52.9 kPa, and 562.2±74.0 kPa, respectively, at 0.17 Green strain. The LADC exhibited a maximum average axial stress of 156.7±18.2 kPa, which was a value comparable to the maximum axial stresses of the constructs. The axial stress–strain averaged curves, shown in Fig. 5, qualitatively suggest that crosslinking time has a strain-stiffening effect for all levels of crosslinking in the axial direction. Strain-stiffening behavior was also noticeable for the LADC, although to a lesser extent.

Fig. 5.

Averaged axial stress–strain curves at 0, 70, and 120 mm Hg for gelatin/fibrinogen constructs crosslinked for 2, 8, and 24 hrs and for the distal section of LADCs. Error bars represent one standard deviation.

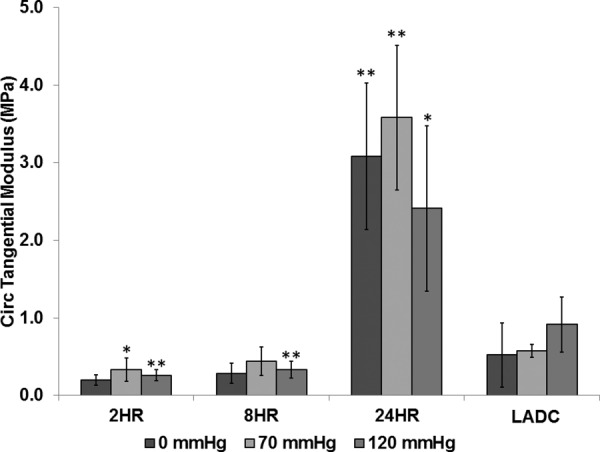

Tangential Moduli Statistical Results.

CTM values were determined at 0, 70, and 120 mm Hg for each replicate for all experimental groups at 0 g, 10 g, and 30 g axial load. Two-way ANOVA tests were performed to determine the effect of axial load and crosslinking time. The results revealed that the effect of the cross-linking time was statistically significant with p values <0.0001 at each pressure. The effects of axial load on the CTM were not significant with p values of 0.77, 0.24, and 0.81 for 0, 70, and 120 mm Hg, respectively. There were no significant interactions between crosslinking time and axial load with p values of 0.62, 0.68, and 0.99 for 0, 70, and 120 mm Hg, respectively. Therefore, the CTM values for the different axial loads were grouped together for each crosslinking time for further statistical processing. Individual two-factor two-tailed t tests were performed comparing the CTM for each construct experimental group at 0, 70, and 120 mm Hg to that of the LADC at 0, 70, and 120 mm Hg, respectively. The comparison of CTM values between construct experimental groups and the LADC is shown in Fig. 6. The CTM of the 2-hrs constructs were not statistically different compared to the LADC at 0 mm Hg with a p value of 0.051. The 8-hrs constructs had CTM values not statistically different compared to the LADC at 0 and 70 mm Hg with p values of 0.14 and 0.06, respectively. All other CTM comparisons between the constructs and the LADC at different pressures showed statistical significance with p values <0.01, with some p values <0.001. The constructs crosslinked for 24 hrs showed statistically significant higher values compared to the LADC for all three pressures. Consistent with Fig. 4, Fig. 6 shows in more detail the qualitative strain-stiffening behavior of the LADC compared to the constructs, while showing that all three construct experimental groups do not show a strain-stiffening behavior in the circumferential direction.

Fig. 6.

CTM comparison between experimental groups and the LADC at 0, 70, and 120 mm Hg. The asterisks indicate statistical significance of the difference between each constructs experimental group and the LADC at the respective pressures, with a single asterisk indicating a p value < 0.01 and double asterisks indicating a p value < 0.001.

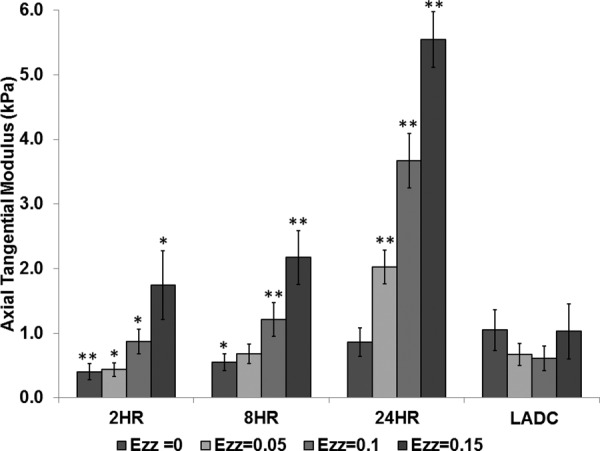

For the axial tests, the ATM values were determined at axial Green strain values of 0, 0.05, 0.1, and 0.15 for each replicate for all experimental groups for pressures of 0, 70, and 120 mm Hg. The two-way ANOVA test indicated that the effect of crosslinking time on ATM was significant with p values <0.0001 at each pressure. The effect of intraluminal pressure on the ATM was not significant with p values of 0.28, 0.70, 0.44, and 0.27 for axial Green strain values of 0, 0.05, 0.1, and 0.15, respectively. There were no significant interactions between intraluminal pressure and cross-linking time with p values of 0.61, 0.99, 0.94, and 0.59 for 0, 0.05, 0.1, and 0.15 axial Green strains, respectively. Therefore, similar to the circumferential test, the ATM for the different pressures were grouped together for each crosslinking time and compared to that of the LADC. The comparison of ATM between construct experimental groups and the LADC is shown in Fig. 7. The ATM of the 8-hrs constructs at 0.05 axial Green strain were not statistically different compared to the LADC at 0.05 axial Green strain with a p value of 0.88, while the ATM of the 24-hrs construct at zero Green strain were not statistically different compared to the LADC at zero Green strain. All other ATM comparisons between the constructs and the LADC at different pressures showed statistical significance with p values <0.05. As shown in Fig. 5, all three crosslinking times displayed an axial strain-stiffening behavior in the axial direction. The LADC did not exhibit the same strain-stiffening for the considered axial Green strain range.

Fig. 7.

Axial tangential modulus comparison between experimental groups and the LADC at axial Green strain values of 0, 0.05, 0.1, and 0.15. The asterisks indicate statistical significance of the difference between each constructs experimental group and the LADC at the respective axial Green strains, with a single asterisk indicating a p value < 0.05 and double asterisks indicating a p value < 0.001.

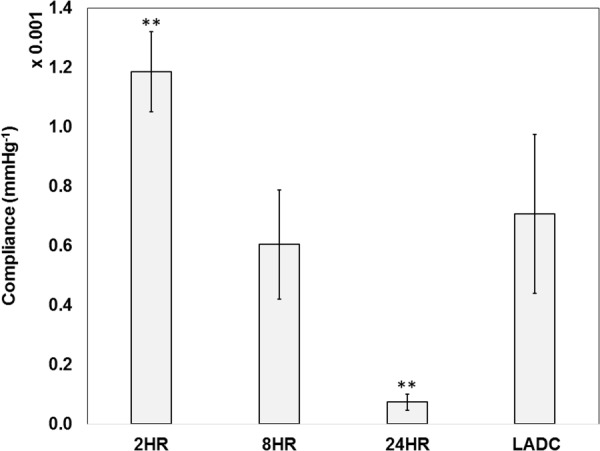

Compliance.

Similar to the CTM, the two-way ANOVA test revealed that the effect of crosslinking time on compliance was significant with a p value <0.0001. The effect of axial load was not significant with a p value of 0.54, with no significant interaction between these two factors with a p value of 0.35. So the compliance values of the same experimental group were grouped together and a two-tailed two-factor t test was performed to compare the compliance values of each experimental group to the LADC. The 8-hrs constructs compliance values (0.00060 ± 0.00018 mm Hg−1) were not significantly different from the LADC (0.00071±0.00027 mm Hg−1) with a p value of 0.36. The 2-hrs and 24-hrs constructs showed compliance values of 0.0012±0.00013 mm Hg−1 and 0.00007±0.00003 mm Hg−1, respectively. Both compliance values were statistically different than that of the LADC with p values <0.001. The comparison of compliance between experimental groups and the LADC is shown in Fig. 8. The only experimental group that exhibited compliance matching was the 8-hrs experimental group. The construct compliance decreases with crosslinking time, which is consistent with trends shown by the circumferential stress–strain curves and CTM graphs.

Fig. 8.

Compliance comparison between experimental groups and the LADC. The asterisks indicate statistical significance of the difference between each constructs experimental group and the LADC at the respective axial Green strains, with double asterisks indicating a p value < 0.001.

Strain Energy Equation Fit

Stress–Strain Surface Plotting.

The circumferential and axial stress–strain Fung fit surfaces for all the experimental groups are shown in Figs. 9 and 10, respectively, which display data for strain ranges in which all three replicates overlap. The strain ranges were restricted by deformability limitations exhibited by the crosslinked material. This is especially noticeable in Fig. 10 where crosslinking time reduces the circumferential strain range. In addition, both Figs. 9 and 10 show that the range of data collected for the LADC is larger compared to the constructs. This is due to the LADC having the capacity to endure higher stresses and strains compared to the gelatin/fibrinogen constructs. The Fung equation constants, R2 values, and the strain energy density values, W, at 30 g axial load for 70 and 120 mm Hg intraluminal pressure for each experimental group are shown in Table 1, which displays the fitted constants for the average, upper limit, and lower limit Fung equation surface plots. Overall, the Fung strain energy equation accurately captures the behaviors of the material with the highest and lowest R2 values for the 24-hrs constructs and LADC at 0.94±0.02 and 0.79±0.04, respectively. Table 1 also displays 1/ 2 as a measure of anisotropy for the constructs.

Fig. 9.

Circumferential stress–strain fitted Fung equation surface plots for each experimental group plotted against data points from all three replicates displayed for fit evaluation and visualization. The surface plots and data points are shown only for strain ranges that overlap between all three replicates.

Fig. 10.

Axial stress–strain fitted Fung equation surface plots for each experimental group plotted against data points from all three replicates displayed for fit evaluation and visualization. The surface plots and data points are shown only for strain ranges that overlap between all three replicates.

Table 1.

Fung strain energy equation constants, 1/2 values, R2 values, and the strain energy density values, W, at 30 g axial load for 70 and 120 mm Hg intraluminal pressure for the average, upper, and lower limit Fung equation surfaces. R2 values compare the Fung equation surface plots to the combined data points of all three replicates for the respective experimental group.

| Group | Dataset | c (kPa) | R2 | W30 g, 70 mm Hg (kPa) | W30 g, 120 mm Hg (kPa) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2HR | Upper limit | 23.7 | 24.0 | 7.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 0.71 | 17.0 | 22.4 |

| Average | 31.0 | 18.4 | 5.6 | 2.6 | 3.3 | 0.90 | 11.1 | 8.3 | |

| Lower limit | 50.5 | 11.4 | 3.4 | 1.7 | 3.3 | 0.91 | 9.9 | 2.6 | |

| 8HR | Upper limit | 54.4 | 17.7 | 9.2 | 3.5 | 1.9 | 0.77 | 31.3 | 10.8 |

| Average | 49.1 | 16.7 | 7.9 | 3.0 | 2.1 | 0.88 | 21.4 | 7.4 | |

| Lower limit | 44.6 | 15.1 | 6.3 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 0.76 | 17.1 | 5.9 | |

| 24HR | Upper limit | 87.3 | 23.7 | 13.1 | 4.5 | 1.8 | 0.94 | 60.1 | 19.4 |

| Average | 83.6 | 22.6 | 12.1 | 4.1 | 1.9 | 0.96 | 41.6 | 11.3 | |

| Lower limit | 80.6 | 21.3 | 10.9 | 3.6 | 2.0 | 0.92 | 37.0 | 9.8 | |

| LADC | Upper limit | 73.5 | 9.0 | 4.8 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 0.79 | 40.6 | 5.0 |

| Average | 87.4 | 7.1 | 3.8 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 0.82 | 31.0 | 2.6 | |

| Lower limit | 126.5 | 4.7 | 2.4 | 0.9 | 1.9 | 0.75 | 12.1 | 0.4 |

Multiphoton Imaging and Fiber Orientation.

Qualitatively, the fiber orientation analysis showed the constructs becoming less fibrous and denser with crosslinking time. There was a slight change in fiber orientation as crosslinking time increased with most of the fibers oriented in the circumferential direction for all three crosslinking times. These MIP images and the fiber orientation distributions are shown in Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.

Representative MIP images obtained from multiphoton imaging (top), and fiber orientation distribution histograms (bottom) of the constructs crosslinked for 2, 8, and 24 hrs. Ninety degree angles correspond to fibers oriented in the circumferential direction and 0 deg and 180 deg angles correspond to fibers oriented in the axial direction.

Discussion

Electrospun cylindrical constructs were fabricated from gelatin/fibrinogen and crosslinked in a GLUT vapor chamber for 2, 8, and 24 hrs. The constructs were then mechanically characterized in a tubular biaxial mechanical configuration and compared to porcine LADC. The constructs crosslinked for 8 hrs showed the most mechanical similarity with the LADC in the circumferential direction, while both the 2 and 8 hrs constructs were mechanically similar to the LADC in the axial direction. The 24-hrs constructs were stiffer in both directions compared to the LADC for most of the studied pressures and axial strains. Statistically, the difference between the CTM values of the 2-hrs constructs and the LADC was not significant at 0 mm Hg. The 8-hrs constructs statistically showed no difference with the LADC for both the 0 and 70 mm Hg. Generally, both the CTM values for the 2 and 8 hrs constructs were within the same order of magnitude, while the CTM values for the 24-hrs constructs were significantly higher than the LADC for all three pressures. The 8-hrs constructs showed no statistical difference with the LADC at 0.05 Green strain, while the 24-hrs constructs showed no statistical difference with the LADC at zero axial Green strain. The 8-hrs constructs were the only experimental group to compliance-match the LADC with no statistically significant difference. Overall, the mechanical behaviors of the 8-hrs constructs were the most similar to that of the LADC in both the circumferential and axial directions out of the three construct experimental groups. From the biaxial stress–strain curves (Figs. 4 and 5), it is safe to assume that all constructs exhibited anisotropic mechanical behavior, which is consistent with the LADC and most soft tissues. In addition, it should be noted that Table 1, which lists a measure of anisotropy, 1/2, for all the experimental groups, suggests that crosslinking reduces the anisotropy of the gelatin/fibrinogen constructs. Table 1 also shows that the 1/2 values of 8-hrs and 24-hrs constructs are comparable to that of the LADC. Also, the stored energy density values, W, for the LADC are comparable to that of the 8-hrs and 24-hrs groups. This suggests that these constructs are capable of storing the necessary energy to function at physiological axial loads and intraluminal pressures.

Fiber orientation realignment is one possible factor to evaluate when considering explanations to the crosslinking effect on mechanical properties. Since the stiffening effect is noticeable in both directions, it would be unlikely that fibers realigned in one direction versus the other, as realigning in one direction would stiffen that specific direction and not the other. The absence of fiber realignment is confirmed in the fiber angle orientation analysis in Fig. 11, where the representative multiphoton images from each crosslinking time qualitatively show no change in fiber angle distribution due to crosslinking. Therefore, it is more likely that crosslinking changes the material properties of the actual gelatin/fibrinogen fibers, which resulted in the overall change in mechanical properties of the constructs. Furthermore, from Fig. 11, most of the fibers seemed to be oriented in the circumferential direction for all three crosslinking times, which may explain the anisotropic behavior of these constructs. The Fung strain energy function was shown to be a suitable constitutive model to model the behavior of all three construct experimental groups and the LADC. The surface plots shown in Figs. 9 and 10 allow a more comprehensive global comparison between the different experimental groups over different circumferential and axial strain ranges. It should be mentioned that we additionally considered the Holzapfel constitutive model [58] as a possible strain energy model to fit to the construct experimental data. However, when evaluated, it was found that the R2 values of the Fung model fit were slightly higher than that of Holzapfel model for all four experimental groups. Furthermore, the Fung model was found to be visually more representative of the experimental data. Based on these findings, the Fung equations were used as the only constitutive model to represent the biomechanical data of the constructs in this study.

Many researchers have mechanically evaluated vascular grafts [9,10,27,34,38,43,59]. Some authors limited their scope to synthetic polymers. Tai et al. [9] fabricated and calculated compliance values of three types of isotropic vascular grafts composed of synthetic polymers using a patented chemical method. Compliance values of the synthetic grafts were compared to that of human muscular artery. The results showed that only the graft made of poly(carbonate)polyurethane compliance matched the artery with average compliance values of 0.00081±0.00004 mm Hg−1 and 0.00080±0.00059 mm Hg−1, respectively. These compliance values were in the same order of magnitude of the compliance values of our 8-hrs constructs and the porcine LADC, which showed compliance values of 0.00060±0.00018 mm Hg−1 and 0.00071±0.00027 mm Hg−1, respectively. In our study, electrospinning was used as the fabricating method to create fibrous constructs which, similar to arteries, exhibited anisotropic mechanical behavior. In contrast to Tai et al. [9], our study focused on using nonsynthetic endogenous biopolymers to fabricate vascular grafts.

A few researcher groups have electrospun biopolymers but provided little information on the evaluation of their mechanical performance [31,32,60]. There are, however, several reports of vascular grafts mechanically characterized assuming they are linear, isotropic, and undergo infinitesimal deformations. Kumar et al. [27] fabricated acellular vascular grafts composed of collagen and elastin and evaluated their grafts using planar tensile testing to quantify graft compliance, burst pressure, and Young's modulus. Likewise, Mitra et al. [59] evaluated the mechanical effect of crosslinking on collagen scaffold tensile strength alone. McClure et al. [34] subjected TEVGs composed of polydioxanone, elastin, and collagen to cyclic uniaxial loading and determined tangential moduli, peak stress, and strain at break. In the case of gelatin, Zhang et al. [38] created electrospun crosslinked and noncrosslinked gelatin flat sheets and briefly mechanically evaluated them by measuring stress and strain and calculating Young's modulus. Balasubramanian et al. [43] electrospun fibrous flat sheets composed of gelatin and fibrinogen crosslinked with GLUT at different ratios including an 80:20 ratio, which is consistent with the ratio used in our study. Their study found the Young's modulus values for their gelatin/fibrinogen scaffolds using uniaxial tests to be 0.46 MPa. This is comparable to the CTM values of our 2-hrs constructs at low pressures (0.20 MPa), but not comparable to the ATM values at low axial strains for the same 2-hrs constructs (0.40 kPa). This may be explained by a higher number of fibers aligned in the circumferential direction as previously shown in Fig. 11. The difference between CTM and ATM values for all our experimental groups highlights the importance of considering the inherent anisotropy of electrospun scaffolds. Our research team is currently more thoroughly investigating the source of mechanical anisotropy by using the MOD and nonlinear optical microscopy to investigate the load-dependent changes in construct microstructural organization.

There are a number researchers who have published studies that fit experimental biomechanical data of native vasculature to constitutive models [61,62], including our research group [52,53,60]. Some studies have used constitutive modeling to fit biomechanical data of developed synthetic TEVGs [64,65]. However, few researchers have used constitutive modeling as a means of comparing TEVGs to native tissue. Mandru et al. [66] characterized porcine carotid and thoracic artery by fitting experimental data to a power-law model and a polynomial equation for hyperelastic material. They also compared the longitudinal Young's moduli value of the native artery to that of TEVGs fabricated from PTFE and Dacron. However, this study does not fit the synthetic TEVG experimental data to the same constitutive models. Our modeling approach fits nonsynthetic TEVGs and native LADC data to the same models for proper comparison of material properties, including anisotropy, as is shown in Table 1.

The current study has a number of limitations. The gelatin/fibrinogen constructs showed little to no strain-stiffening in the circumferential direction compared to the LADC, which showed clear strain-stiffening behavior as shown in Fig. 4. However, none of the constructs reached the circumferential stresses reached by the LADC due to limited construct deformability. It is possible that these constructs could be strain-stiffening in the circumferential direction if allowed to experience similar circumferential stress by possibly increasing the pressure, increasing the undeformed radius, and/or decreasing the undeformed thickness. Furthermore, the LADC may display strain-stiffening behavior in the axial direction at higher axial strains not shown in Fig. 5. However, the comparison was limited by low allowable axial strains of the 2-hrs construct experimental group, which were stretched to failure around an axial Green strain of 0.18. These strain limitations are more clearly shown in the Fung strain energy surface plots displayed in Figs. 9 and 10, where the LADC surface plot does extend over a larger axial strain compared to the constructs in both directions. Future studies in our laboratory will investigate a more clear understanding between crosslinking time and compliance. The addition of other biopolymers, such as collagen and tropoelastin, will be investigated as means to provide the constructs higher deformability, which could allow these constructs to reach the necessary stresses and strains exhibited by the LADC. Suture retention and burst pressure of the gelatin/fibrinogen constructs were not evaluated in this study. These properties are important indicators to the suitability of constructs to be transplanted and will be further investigated by our research group. Only noncellularized electrospun constructs were evaluated in this study. However, we are currently conducting experiments to determine the effects of SMC-mediated gelatin/fibrinogen remodeling and ECM deposition on construct mechanical properties. Finally, our previous paper [44] demonstrated that our gelatin/fibrinogen materials do promote cell division, migration, and collagen deposition ex vivo. Even though ex vivo experiments do not always translate into in vivo experiments, we do believe that if our acellular constructs were implanted in vivo, cell infiltration and native construct remodeling would occur. The degree to which this will lead to function or dysfunction of our construct postimplantation is currently unknown and will only be revealed after in vivo studies, something that is currently ongoing in our laboratory.

The current study evaluates the mechanical behavior of gelatin/fibrinogen cylindrical constructs crosslinked with GLUT for three different periods of time. The constructs are compared to native porcine LADC and the collected data suggested that some of the construct groups behaved very similarly to the LADC. The results of this study suggest that it is possible to modify the mechanical properties to meet specifications required by vascular graft transplantation through manipulating the crosslinking time. Complete mechanical biaxial characterization of tubular biopolymer constructs is currently lacking in the literature. This study offers a comprehensive method of evaluating electrospun crosslinked biopolymer cylindrical constructs in the circumferential and axial directions at physiological conditions. However, the effect of crosslinking on biocompatibility and biodegradability is still largely unknown. Our laboratory has already shown that SMCs can grow with excellent viability on the gelatin/fibrinogen fibers used to fabricate the constructs discussed in this paper after being crosslinked with GLUT [44]. Preliminary studies in our laboratory have qualitatively suggested that seeded SMCs have a significant mechanical effect on gelatin/fibrinogen constructs. Future studies will further investigate this effect and will be focused on the mechanism in which SMCs remodel the fibrous constructs, which would shed light on methods of reducing manufacturing time for TEVGs while maintaining mechanical integrity. Blood compatibility and thrombogenicity remain important factors for these constructs and should be evaluated. To accommodate this concern, possible modifications to the constructs could include surface modification to the lumen of the construct by making it more hydrophilic, which would inhibit protein absorption. Our laboratory is also currently focused on endothelializing the construct lumen of our constructs. The immunogenicity and inflammation due to the presence of the gelatin/fibrinogen construct is another concern. While gelatin has been shown to have a reduced antigenic response in animal models, Telemeco et al. [67] reported that grafts made of electrospun gelatin produced a foreign body giant cell response and fibrosis. It should be noted that in vivo physiological responses depend on the material chemistry of the graft. Gelatin can have different exposed functional groups, depending on the extraction process and source [41]. In addition, the foreign body reaction that causes inflammation depends on the location of the implant. The gelatin grafts developed by Telemeco et al. were not placed in their animal model in a functional position as they were implanted subcutaneously and not as vascular conduits. Furthermore, preliminary results from our recent ex vivo experiments have shown our gelatin/fibrinogen constructs to be biodegradable, and therefore, any signs of inflammation and immunogenicity will most likely be reduced as the gelatin becomes degraded. Finally, for full clinical translational use of this approach one must consider issues related to potential toxicities of the crosslinking agent used in this study. While GLUT is utilized for preservation of implant biologic materials, such as valves, cartilage, and tendons [25,68–70], there have been many studies that reported information regarding cytotoxicity and immunogenicity of using GLUT as a crosslinking agent in the literature [71–74]. Most of these studies do not discuss the in vivo responses due to the presence of biopolymer grafts crosslinked with GLUT vapor. Tillman et al. [75] investigated the patency and structural integrity of PCL/collagen constructs crosslinked with GLUT and found that their constructs do not elicit abnormal inflammatory responses. Similarly, we expect that our gelatin/fibrinogen GLUT-crosslinked constructs will have minimal immunoresponse after being implanted in an animal model. All these different factors are important considerations in developing suitable clinical tissue-engineered constructs for use in the benefit of CVD patients.

The long-term goal of this project is to use crosslinking and SMC cell culture to modulate the biomechanical properties of small-diameter biopolymer constructs to match the different properties of native artery. The purpose of this manuscript was to evaluate if an acellular construct could be compliance-matched to native tissue. Our laboratory group is currently in the process of implanting our acellular constructs in a rat animal model to evaluate the feasibility and in vivo response of our TEVG. Our laboratory is also initiating ex vivo studies focused exclusively on cell-mediated ECM remodeling and deposition in a tubular biaxial bioreactor designed for this purpose. In these bioreactors, we will also be able to monitor construct remodeling and cell migration/proliferation using intravital nonlinear optical microscopy. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to quantify and compare the anisotropic behavior of electrospun biopolymers to that of native porcine coronary tissue. This was accomplished using the custom-made MOD that evaluated the anisotropic cylindrical geometries using tubular biaxial protocols, which serves as a more comprehensive evaluation of the mechanical suitability of electrospun biopolymer constructs for use as vascular grafts. The biaxial mechanical evaluation shown in the current study is an important first step of many to transitioning over to performing preclinical in vivo studies in efforts to result in advanced customized cell-based TEVG development.

Acknowledgment

This research was funded by the NIH, Grant No. NHLBI-1R21HL111990-01A1 to JPVG. The imaging was performed on an NIH sponsored shared device NIH/NCRRS10RR023737. We would also like to acknowledge Jamie Hernandez, Corina MacIsaac, and Joshua Uhlorn for their assistance and support.

Contributor Information

E. Tamimi, Graduate Interdisciplinary Program , of Biomedical Engineering, , The University of Arizona, , Tucson, AZ 85721

D. C. Ardila, Graduate Interdisciplinary Program , of Biomedical Engineering, , The University of Arizona, , Tucson, AZ 85721

D. G. Haskett, Graduate Interdisciplinary Program , of Biomedical Engineering, , The University of Arizona, , Tucson, AZ 85721

T. Doetschman, Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, , The University of Arizona, , Tucson, AZ 85721; Sarver Heart Center, , The University of Arizona, , Tucson, AZ 85724; BIO5 Institute for Biocollaborative Research, , The University of Arizona, , Tucson, AZ 85721

M. J. Slepian, Graduate Interdisciplinary Program , of Biomedical Engineering, , The University of Arizona, , Tucson, AZ 85721; Sarver Heart Center, , The University of Arizona, , Tucson, AZ 85724; BIO5 Institute for Biocollaborative Research, , The University of Arizona, , Tucson, AZ 85721; Department of Biomedical Engineering, , The University of Arizona, , Tucson, AZ 85721; ACABI, The Arizona Center for Accelerated , BioMedical Innovation, , The University of Arizona, , Tucson, AZ 85721

R. S. Kellar, Center for Bioengineering Innovation, , Northern Arizona University, , Flagstaff, AZ 86011; Department of Mechanical Engineering, , Northern Arizona University, , Flagstaff, AZ 86011; Department of Biological Sciences, , Northern Arizona University, , Flagstaff, AZ 86011

J. P. Vande Geest, Associate Professor , Graduate Interdisciplinary Program , of Biomedical Engineering, , The University of Arizona, , Tucson, AZ 85721;; Department of Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering, , The University of Arizona, , Tucson, AZ 85721; BIO5 Institute for Biocollaborative Research, , The University of Arizona, , Tucson, AZ 85721; Department of Biomedical Engineering, , The University of Arizona, , Tucson, AZ 85721 , e-mail: jpv1@email.arizona.edu

References

- [1]. Go, A. S. , Mozaffarian, D. , Roger, V. L. , Benjamin, E. J. , Berry, J. D. , Blaha, M. J. , Dai, S. , Ford, E. S. , Fox, C. S. , Franco, S. , Fullerton, H. J. , Gillespie, C. , Hailpern, S. M. , Heit, J. A. , Howard, V. J. , Huffman, M. D. , Judd, S. E. , Kissela, B. M. , Kittner, S. J. , Lackland, D. T. , Lichtman, J. H. , Lisabeth, L. D. , Mackey, R. H. , Magid, D. J. , Marcus, G. M. , Marelli, A. , Matchar, D. B. , McGuire, D. K. , Mohler, E. R. , 3rd, Moy, C. S. , Mussolino, M. E. , Neumar, R. W. , Nichol, G. , Pandey, D. K. , Paynter, N. P. , Reeves, M. J. , Sorlie, P. D. , Stein, J. , Towfighi, A. , Turan, T. N. , Virani, S. S. , Wong, N. D. , Woo, D. , and Turner, M. B. , 2014, “ Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2014 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association,” Circulation, 129(3), pp. e28–e292. 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Kurobe, H. , Maxfield, M. W. , Breuer, C. K. , and Shinoka, T. , 2012, “ Concise Review: Tissue-Engineered Vascular Grafts for Cardiac Surgery: Past, Present, and Future,” Stem Cells Transl. Med., 1(7), pp. 566–571. 10.5966/sctm.2012-0044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Kannan, R. Y. , Salacinski, H. J. , Butler, P. E. , Hamilton, G. , and Seifalian, A. M. , 2005, “ Current Status of Prosthetic Bypass Grafts: A Review,” J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B, 74(1), pp. 570–581. 10.1002/jbm.b.30247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Rocco, K. A. , Maxfield, M. W. , Best, C. A. , Dean, E. W. , and Breuer, C. K. , 2014, “ In Vivo Applications of Electrospun Tissue-Engineered Vascular Grafts: A Review,” Tissue Eng. Part B, 20(6), pp. 628–640. 10.1089/ten.teb.2014.0123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. He, J. , Qin, T. , Liu, Y. , Li, X. , Li, D. , and Jin, Z. , 2014, “ Electrospinning of Nanofibrous Scaffolds With Continuous Structure and Material Gradients,” Mater. Lett., 137, pp. 393–397. 10.1016/j.matlet.2014.09.045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Hong, Y. , Ye, S. H. , Nieponice, A. , Soletti, L. , Vorp, D. A. , and Wagner, W. R. , 2009, “ A Small Diameter, Fibrous Vascular Conduit Generated From a Poly(Ester Urethane)Urea and Phospholipid Polymer Blend,” Biomaterials, 30(13), pp. 2457–2467. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Nieponice, A. , Soletti, L. , Guan, J. , Deasy, B. M. , Huard, J. , Wagner, W. R. , and Vorp, D. A. , 2008, “ Development of a Tissue-Engineered Vascular Graft Combining a Biodegradable Scaffold, Muscle-Derived Stem Cells and a Rotational Vacuum Seeding Technique,” Biomaterials, 29(7), pp. 825–833. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.10.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Soletti, L. , Hong, Y. , Guan, J. , Stankus, J. J. , El-Kurdi, M. S. , Wagner, W. R. , and Vorp, D. A. , 2010, “ A Bilayered Elastomeric Scaffold for Tissue Engineering of Small Diameter Vascular Grafts,” Acta Biomater., 6(1), pp. 110–122. 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.06.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Tai, N. R. , Salacinski, H. J. , Edwards, A. , Hamilton, G. , and Seifalian, A. M. , 2000, “ Compliance Properties of Conduits Used in Vascular Reconstruction,” Br. J. Surg., 87(11), pp. 1516–1524. 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01566.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. McClure, M. J. , Sell, S. A. , Simpson, D. G. , Walpoth, B. H. , and Bowlin, G. L. , 2010, “ A Three-Layered Electrospun Matrix to Mimic Native Arterial Architecture Using Polycaprolactone, Elastin, and Collagen: A Preliminary Study,” Acta Biomater., 6(7), pp. 2422–2433. 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Merkle, V. , Zeng, L. , Teng, W. , Slepian, M. , and Wu, X. , 2013, “ Gelatin Shells Strengthen Polyvinyl Alcohol Core–Shell Nanofibers,” Polymer, 54(21), pp. 6003–6007. 10.1016/j.polymer.2013.08.056 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Merkle, V. M. , Zeng, L. , Slepian, M. J. , and Wu, X. , 2014, “ Core-Shell Nanofibers: Integrating the Bioactivity of Gelatin and the Mechanical Property of Polyvinyl Alcohol,” Biopolymers, 101(4), pp. 336–346. 10.1002/bip.22367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Stitzel, J. D. , Pawlowski, K. J. , Wnek, G. E. , Simpson, D. G. , and Bowlin, G. L. , 2001, “ Arterial Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation on a Novel Biomimicking, Biodegradable Vascular Graft Scaffold,” J. Biomater. Appl., 16(1), pp. 22–33. 10.1106/U2UU-M9QH-Y0BB-5GYL [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Wise, S. G. , Byrom, M. J. , Waterhouse, A. , Bannon, P. G. , Weiss, A. S. , and Ng, M. K. , 2011, “ A Multilayered Synthetic Human Elastin/Polycaprolactone Hybrid Vascular Graft With Tailored Mechanical Properties,” Acta Biomater., 7(1), pp. 295–303. 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Bergmeister, H. , Seyidova, N. , Schreiber, C. , Strobl, M. , Grasl, C. , Walter, I. , Messner, B. , Baudis, S. , Fröhlich, S. , Marchetti-Deschmann, M. , Griesser, M. , di Franco, M. , Krssak, M. , Liska, R. , and Schima, H. , 2015, “ Biodegradable, Thermoplastic Polyurethane Grafts for Small Diameter Vascular Replacements,” Acta Biomater., 11, pp. 104–113. 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Catto, V. , Fare, S. , Cattaneo, I. , Figliuzzi, M. , Alessandrino, A. , Freddi, G. , Remuzzi, A. , and Tanzi, M. C. , 2015, “ Small Diameter Electrospun Silk Fibroin Vascular Grafts: Mechanical Properties, Ex Vivo Biodegradability, and In Vivo Biocompatibility,” Mater. Sci. Eng. C: Mater. Biol. Appl., 54, pp. 101–111. 10.1016/j.msec.2015.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Hu, Z.-J. , Li, Z.-L. , Hu, L.-Y. , He, W. , Liu, R.-M. , Qin, Y.-S. , and Wang, S.-M. , 2012, “ The In Vivo Performance of Small-Caliber Nanofibrous Polyurethane Vascular Grafts,” BMC Cardiovasc. Disord., 12(1), p. 115. 10.1186/1471-2261-12-115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Matsumura, G. , Isayama, N. , Matsuda, S. , Taki, K. , Sakamoto, Y. , Ikada, Y. , and Yamazaki, K. , 2013, “ Long-Term Results of Cell-Free Biodegradable Scaffolds for In Situ Tissue Engineering of Pulmonary Artery in a Canine Model,” Biomaterials, 34(27), pp. 6422–6428. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.05.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Udelsman, B. V. , Khosravi, R. , Miller, K. S. , Dean, E. W. , Bersi, M. R. , Rocco, K. , Yi, T. , Humphrey, J. D. , and Breuer, C. K. , 2014, “ Characterization of Evolving Biomechanical Properties of Tissue Engineered Vascular Grafts in the Arterial Circulation,” J. Biomech., 47(9), pp. 2070–2079. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Zhang, L. , Zhou, J. , Lu, Q. , Wei, Y. , and Hu, S. , 2008, “ A Novel Small-Diameter Vascular Graft: in vivo Behavior of Biodegradable Three-Layered Tubular Scaffolds,” Biotechnol. Bioeng., 99(4), pp. 1007–1015. 10.1002/bit.21629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Shinoka, T. , Shum-Tim, D. , Ma, P. X. , Tanel, R. E. , Isogai, N. , Langer, R. , Vacanti, J. P. , and Mayer, J. E., Jr. , 1998, “ Creation of Viable Pulmonary Artery Autografts Through Tissue Engineering,” J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg., 115(3), pp. 536–546. 10.1016/S0022-5223(98)70315-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Wang, S. , Mo, X. M. , Jiang, B. J. , Gao, C. J. , Wang, H. S. , Zhuang, Y. G. , and Qiu, L. J. , 2013, “ Fabrication of Small-Diameter Vascular Scaffolds by Heparin-Bonded P(LLA-CL) Composite Nanofibers to Improve Graft Patency,” Int. J. Nanomed., 8, pp. 2131–2139. 10.2147/IJN.S44956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Catto, V. , Fare, S. , Freddi, G. , and Tanzi, M. C. , 2014, “ Vascular Tissue Engineering: Recent Advances in Small Diameter Blood Vessel Regeneration,” ISRN Vasc. Med., 2014, p. 923030. 10.1155/2014/923030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Nemeno-Guanzon, J. G. , Lee, S. , Berg, J. R. , Jo, Y. H. , Yeo, J. E. , Nam, B. M. , Koh, Y.-G. , and Lee, J. I. , 2012, “ Trends in Tissue Engineering for Blood Vessels,” J. Biomed. Biotechnol., 2012, p. 956345. 10.1155/2012/956345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Salles, C. A. , Buffolo, E. , Andrade, J. C. , Palma, J. H. , Silva, R. R. , Santiago, R. , Casagrande, I. S. , and Moreira, M. C. , 1998, “ Mitral Valve Replacement With Glutaraldehyde Preserved Aortic Allografts,” Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg., 13(2), pp. 135–143. 10.1016/S1010-7940(97)00320-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Huang, Z.-M. , Zhang, Y. Z. , Ramakrishna, S. , and Lim, C. T. , 2004, “ Electrospinning and Mechanical Characterization of Gelatin Nanofibers,” Polymer, 45(15), pp. 5361–5368. 10.1016/j.polymer.2004.04.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Kumar, V. A. , Caves, J. M. , Haller, C. A. , Dai, E. , Liu, L. , Grainger, S. , and Chaikof, E. L. , 2013, “ Acellular Vascular Grafts Generated From Collagen and Elastin Analogs,” Acta Biomater., 9(9), pp. 8067–8074. 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.05.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. L'Heureux, N. , Paquet, S. , Labbe, R. , Germain, L. , and Auger, F. A. , 1998, “ A Completely Biological Tissue-Engineered Human Blood Vessel,” FASEB J., 12(1), pp. 47–56. http://www.fasebj.org/content/12/1/47.short [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. Matthews, J. A. , Wnek, G. E. , Simpson, D. G. , and Bowlin, G. L. , 2002, “ Electrospinning of Collagen Nanofibers,” Biomacromolecules, 3(2), pp. 232–238. 10.1021/bm015533u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30]. McManus, M. C. , Boland, E. D. , Koo, H. P. , Barnes, C. P. , Pawlowski, K. J. , Wnek, G. E. , Simpson, D. G. , and Bowlin, G. L. , 2006, “ Mechanical Properties of Electrospun Fibrinogen Structures,” Acta Biomater., 2(1), pp. 19–28. 10.1016/j.actbio.2005.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31]. Nivison-Smith, L. , Rnjak, J. , and Weiss, A. S. , 2010, “ Synthetic Human Elastin Microfibers: Stable Crosslinked Tropoelastin and Cell Interactive Constructs for Tissue Engineering Applications,” Acta Biomater., 6(2), pp. 354–359. 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32]. Perumcherry, S. R. , Chennazhi, K. P. , Nair, S. V. , Menon, D. , and Afeesh, R. , 2011, “ A Novel Method for the Fabrication of Fibrin-Based Electrospun Nanofibrous Scaffold for Tissue-Engineering Applications,” Tissue Eng. Part C, 17(11), pp. 1121–1130. 10.1089/ten.tec.2010.0734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33]. Boland, E. D. , Matthews, J. A. , Pawlowski, K. J. , Simpson, D. G. , Wnek, G. E. , and Bowlin, G. L. , 2004, “ Electrospinning Collagen and Elastin: Preliminary Vascular Tissue Engineering,” Front. Biosci.: J. Virtual Library, 9, pp. 1422–1432. 10.2741/1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34]. McClure, M. J. , Sell, S. , Simpson, D. , and Bowlin, G. , 2009, “ Electrospun Polydioxanone, Elastin, and Collagen Vascular Scaffolds: Uniaxial Cyclic Distension,” J. Eng. Fibers Fabr., 4(2), pp. 18–25.http://www.jeffjournal.org/papers/Volume4/4.2Bowlin.pdf [Google Scholar]

- [35]. Wong, C. S. , Liu, X. , Xu, Z. , Lin, T. , and Wang, X. , 2013, “ Elastin and Collagen Enhances Electrospun Aligned Polyurethane as Scaffolds for Vascular Graft,” J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med., 24(8), pp. 1865–1874. 10.1007/s10856-013-4937-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36]. Zeugolis, D. I. , Khew, S. T. , Yew, E. S. , Ekaputra, A. K. , Tong, Y. W. , Yung, L. Y. , Hutmacher, D. W. , Sheppard, C. , and Raghunath, M. , 2008, “ Electro-Spinning of Pure Collagen Nano-Fibres—Just an Expensive Way to Make Gelatin?” Biomaterials, 29(15), pp. 2293–2305. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37]. McClure, M. J. , Sell, S. , Barnes, C. , Bowen, W. , and Bowlin, G. , 2008, “ Cross-Linking Electrospun Polydioxanone-Soluble Elastin Blends: Material Characterization,” J. Eng. Fibers Fabr., 3(1), pp. 1–10.http://www.jeffjournal.org/papers/Volume3/Bowlin.pdf [Google Scholar]

- [38]. Zhang, S. , Huang, Y. , Yang, X. , Mei, F. , Ma, Q. , Chen, G. , Ryu, S. , and Deng, X. , 2009, “ Gelatin Nanofibrous Membrane Fabricated by Electrospinning of Aqueous Gelatin Solution for Guided Tissue Regeneration,” J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A, 90(3), pp. 671–679. 10.1002/jbm.a.32136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39]. Sell, S. A. , Wolfe, P. S. , Garg, K. , McCool, J. M. , Rodriguez, I. A. , and Bowlin, G. L. , 2010, “ The Use of Natural Polymers in Tissue Engineering: A Focus on Electrospun Extracellular Matrix Analogues,” Polymers, 2(4), pp. 522–553. 10.3390/polym2040522 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [40]. Grover, C. N. , Gwynne, J. H. , Pugh, N. , Hamaia, S. , Farndale, R. W. , Best, S. M. , and Cameron, R. E. , 2012, “ Crosslinking and Composition Influence the Surface Properties, Mechanical Stiffness and Cell Reactivity of Collagen-Based Films,” Acta Biomater., 8(8), pp. 3080–3090. 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41]. Rose, J. , Pacelli, S. , Haj, A. , Dua, H. , Hopkinson, A. , White, L. , and Rose, F. , 2014, “ Gelatin-Based Materials in Ocular Tissue Engineering,” Materials, 7(4), pp. 3106–3135. 10.3390/ma7043106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42]. Gorgieva, S. , and Kokol, V. , 2011, “Collagen-vs. Gelatine-Based Biomaterials and Their Biocompatibility: Review and Perspectives,” Biomaterials Applications for Nanomedicine, R. Pignatello, ed., INTECH, Rijeka, Croatia: 10.5772/24118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [43]. Balasubramanian, P. , Prabhakaran, M. P. , Kai, D. , and Ramakrishna, S. , 2013, “ Human Cardiomyocyte Interaction With Electrospun Fibrinogen/Gelatin Nanofibers for Myocardial Regeneration,” J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed., 24(14), pp. 1660–1675. 10.1080/09205063.2013.789958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44]. Ardila, D. C. , Tamimi, E. , Danford, F. L. , Haskett, D. G. , Kellar, R. S. , Doetschman, T. , and Vande Geest, J. P. , 2014, “ TGFbeta2 Differentially Modulates Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation and Migration in Electrospun Gelatin-Fibrinogen Constructs,” Biomaterials, 37C, pp. 164–173. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.10.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45]. Ghista, D. , and Kabinejadian, F. , 2013, “ Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Hemodynamics and Anastomosis Design: A Biomedical Engineering Review,” Biomed. Eng. Online, 12(1), p. 129. 10.1186/1475-925X-12-129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46]. Amoroso, N. J. , D'Amore, A. , Hong, Y. , Rivera, C. P. , Sacks, M. S. , and Wagner, W. R. , 2012, “ Microstructural Manipulation of Electrospun Scaffolds for Specific Bending Stiffness for Heart Valve Tissue Engineering,” Acta Biomater., 8(12), pp. 4268–4277. 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47]. Liu, S. , Dong, C. , Lu, G. , Lu, Q. , Li, Z. , Kaplan, D. L. , and Zhu, H. , 2013, “ Bilayered Vascular Grafts Based on Silk Proteins,” Acta Biomater., 9(11), pp. 8991–9003. 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.06.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48]. Naito, Y. , Lee, Y. U. , Yi, T. , Church, S. N. , Solomon, D. , Humphrey, J. D. , Shin'oka, T. , and Breuer, C. K. , 2014, “ Beyond Burst Pressure: Initial Evaluation of the Natural History of the Biaxial Mechanical Properties of Tissue-Engineered Vascular Grafts in the Venous Circulation Using a Murine Model,” Tissue Eng. Part A, 20(1–2), pp. 346–355. 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49]. Wang, F. , Mohammed, A. , Li, C. , Ge, P. , Wang, L. , and King, M. W. , 2014, “ Degradable/Non-Degradable Polymer Composites for In-Situ Tissue Engineering Small Diameter Vascular Prosthesis Application,” Biomed. Mater. Eng., 24(6), pp. 2127–2133. 10.3233/BME-141023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50]. Chung, J. , and Li, J. K. , 2004, “ Hemodynamic Simulation of Vascular Prosthesis Altering Pulse Wave Propagation,” Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, (IEMBS '04), Sept. 1–5, Vol. 5, pp. 3678–3680. 10.1109/IEMBS.2004.1404033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51]. Keyes, J. T. , Lockwood, D. R. , Utzinger, U. , Montilla, L. G. , Witte, R. S. , and Vande Geest, J. P. , 2013, “ Comparisons of Planar and Tubular Biaxial Tensile Testing Protocols of the Same Porcine Coronary Arteries,” Ann. Biomed. Eng., 41(7), pp. 1579–1591. 10.1007/s10439-012-0679-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52]. Haskett, D. , Speicher, E. , Fouts, M. , Larson, D. , Azhar, M. , Utzinger, U. , and Vande Geest, J. P. , 2012, “ The Effects of Angiotensin II on the Coupled Microstructural and Biomechanical Response of C57BL/6 Mouse Aorta,” J. Biomech., 45(2), pp. 722–729. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53]. Haskett, D. G. , Azhar, M. , Utzinger, U. , and Vande Geest, J. P. , 2013, “ Progressive Alterations in Microstructural Organization and Biomechanical Response in the apoE Mouse Model of Aneurysm,” Biomatter, 3(2), p. e24648. 10.4161/biom.24648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54]. Haskett, D. G. , Doyle, J. , Gard, C. , Chen, H. , Ball, C. , Estabrook, M. A. , Encinas, A. C. , Dietz, H. C. , Utzinger, U. , Vande Geest, J. P. , and Axzhar, M. , 2012, “ Altered Tissue Behavior of Non-Aneurysmal Descending Thoracic Aorta in the Mouse Model of Marfan Syndrome,” Cell Tissue Res., 347(1), pp. 267–277. 10.1007/s00441-011-1270-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55]. Keyes, J. T. , Borowicz, S. M. , Rader, J. H. , Utzinger, U. , Azhar, M. , and Vande Geest, J. P. , 2011, “ Design and Demonstration of a Microbiaxial Optomechanical Device for Multiscale Characterization of Soft Biological Tissues With Two-Photon Microscopy,” Microsc. Microanal., 17(2), pp. 167–175. 10.1017/S1431927610094341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56]. Keyes, J. T. , Utzinger, U. , and Vande Geest, J. P. , 2011, “ Adaptation of a Two-Photon-Microscope-Interfacing Planar Biaxial Testing Device for the Microstructural and Macroscopic Characterization of Small Tubular Tissue Specimens,” ASME J. Biomech. Eng., 133(7), p. 075001. 10.1115/1.4004495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57]. Hearn, E. J. , 1997, “ Thick Cylinders,” Mechanics of Materials 1, 3rd ed., Hearn E. J., ed., Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, pp. 215–253. 10.1016/B978-075063265-2/50011-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [58]. Haskett, D. , Johnson, G. , Zhou, A. , Utzinger, U. , and Vande Geest, J. , 2010, “ Microstructural and Biomechanical Alterations of the Human Aorta as a Function of Age and Location,” Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol., 9(6), pp. 725–736. 10.1007/s10237-010-0209-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59]. Mitra, T. , Sailakshmi, G. , Gnanamani, A. , and Mandal, A. B. , 2011, “ Cross-Linking With Acid Chlorides Improves Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Collagen Based Biopolymer Material,” Thermochim. Acta, 525(1–2), pp. 50–55. 10.1016/j.tca.2011.07.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [60]. Dong, B. , Arnoult, O. , Smith, M. E. , and Wnek, G. E. , 2009, “ Electrospinning of Collagen Nanofiber Scaffolds From Benign Solvents,” Macromol. Rapid Commun., 30(7), pp. 539–542. 10.1002/marc.200800634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61]. Caulk, A. W. , Nepiyushchikh, Z. V. , Shaw, R. , Dixon, J. B. , and Gleason, R. L. , 2015, “ Quantification of the Passive and Active Biaxial Mechanical Behaviour and Microstructural Organization of Rat Thoracic Ducts,” J. R. Soc. Interface, 12(108), p. 20150280. 10.1016/j.tem.2010.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62]. Wan, W. , Dixon, J. B. , and Gleason, J., Jr. , and Rudolph, L. , 2012, “ Constitutive Modeling of Mouse Carotid Arteries Using Experimentally Measured Microstructural Parameters,” Biophys. J., 102(12), pp. 2916–2925. 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.04.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63]. Keyes, J. T. , Lockwood, D. R. , Simon, B. R. , and Vande Geest, J. P. , 2013, “ Deformationally Dependent Fluid Transport Properties of Porcine Coronary Arteries Based on Location in the Coronary Vasculature,” J. Mech. Behav. Biomed Mater., 17, pp. 296–306. 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2012.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64]. Dahl, S. L. M. , Vaughn, M. E. , Hu, J.-J. , Driessen, N. J. B. , Baaijens, F. P. T. , Humphrey, J. D. , and Niklason, L. E. , 2008, “ A Microstructurally Motivated Model of the Mechanical Behavior of Tissue Engineered Blood Vessels,” Ann. Biomed. Eng., 36(11), pp. 1782–1792. 10.1007/s10439-008-9554-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65]. Zaucha, M. T. , Gauvin, R. , Auger, F. A. , Germain, L. , and Gleason, R. L. , 2011, “ Biaxial Biomechanical Properties of Self-Assembly Tissue-Engineered Blood Vessels,” J. R. Soc. Interface, 8(55), pp. 244–256. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.171600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66]. Mandru, M. , Ionescu, C. , and Chirita, M. , 2009, “ Modelling Mechanical Properties in Native and Biomimetically Formed Vascular Grafts,” J. Bionic Eng., 6(4), pp. 371–377. 10.1016/S1672-6529(08)60137-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [67]. Telemeco, T. A. , Ayres, C. , Bowlin, G. L. , Wnek, G. E. , Boland, E. D. , Cohen, N. , Baumgarten, C. M. , Mathews, J. , and Simpson, D. G. , 2005, “ Regulation of Cellular Infiltration Into Tissue Engineering Scaffolds Composed of Submicron Diameter Fibrils Produced by Electrospinning,” Acta Biomater., 1(4), pp. 377–385. 10.1016/j.actbio.2005.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68]. Chauvaud, S. , Jebara, V. , Chachques, J. C. , el Asmar, B. , Mihaileanu, S. , Perier, P. , Dreyfus, G. , Relland, J. , Couetil, J. P. , and Carpentier, A. , 1991, “ Valve Extension With Glutaraldehyde-Preserved Autologous Pericardium. Results in Mitral Valve Repair,” J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg., 102(2), pp. 171–177; Discussion 177–178.http://europepmc.org/abstract/med/1907700 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69]. Hunziker, E. B. , Lippuner, K. , and Shintani, N. , 2014, “ How Best to Preserve and Reveal the Structural Intricacies of Cartilaginous Tissue,” Matrix Biol., 39, pp. 33–43. 10.1016/j.matbio.2014.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70]. Ramesh, R. , Kumar, N. , Sharma, A. K. , Maiti, S. K. , and Singh, G. R. , 2003, “ Acellular and Glutaraldehyde-Preserved Tendon Allografts for Reconstruction of Superficial Digital Flexor Tendon in Bovines: Part I—Clinical, Radiological and Angiographical Observations,” J. Vet. Med., 50(10), pp. 511–519. 10.1111/j.1439-0442.2004.00578.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71]. Gough, J. E. , Scotchford, C. A. , and Downes, S. , 2002, “ Cytotoxicity of Glutaraldehyde Crosslinked Collagen/Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) Films is by the Mechanism of Apoptosis,” J. Biomed. Mater. Res., 61(1), pp. 121–130. 10.1002/jbm.10145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72]. Jayakrishnan, A. , and Jameela, S. R. , 1996, “ Glutaraldehyde as a Fixative in Bioprostheses and Drug Delivery Matrices,” Biomaterials, 17(5), pp. 471–484. 10.1016/0142-9612(96)82721-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73]. Schmidt, C. E. , and Baier, J. M. , 2000, “ Acellular Vascular Tissues: Natural Biomaterials for Tissue Repair and Tissue Engineering,” Biomaterials, 21(22), pp. 2215–2231. 10.1016/S0142-9612(00)00148-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74]. Zhai, W. , Zhang, H. , Wu, C. , Zhang, J. , Sun, X. , Zhang, H. , Zhu, Z. , and Chang, J. , 2014, “ Crosslinking of Saphenous Vein ECM by Procyanidins for Small Diameter Blood Vessel Replacement,” J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B, 102(6), pp. 1190–1198. 10.1002/jbm.b.33102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75]. Tillman, B. W. , Yazdani, S. K. , Lee, S. J. , Geary, R. L. , Atala, A. , and Yoo, J. J. , 2009, “ The In Vivo Stability of Electrospun Polycaprolactone-Collagen Scaffolds in Vascular Reconstruction,” Biomaterials, 30(4), pp. 583–588. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]