Abstract

Background

The etiology of non-genetic intellectual disability (ID) is not fully known, and we aimed to identify the prenatal, perinatal and neonatal risk factors for ID.

Method

PubMed and Embase databases were searched for studies that examined the association between pre-, peri- and neonatal factors and ID risk (keywords “intellectual disability” or “mental retardation” or “ID” or “MR” in combination with “prenatal” or “pregnancy” or “obstetric” or “perinatal” or “neonatal”. The last search was updated on September 15, 2015. Summary effect estimates (pooled odds ratios) were calculated for each risk factor using random effects models, with tests for heterogeneity and publication bias.

Results

Seventeen studies with 55,344 patients and 5,723,749 control individuals were eligible for inclusion in our analysis, and 16 potential risk factors were analyzed. Ten prenatal factors (advanced maternal age, maternal black race, low maternal education, third or more parity, maternal alcohol use, maternal tobacco use, maternal diabetes, maternal hypertension, maternal epilepsy and maternal asthma), one perinatal factor (preterm birth) and two neonatal factors (male sex and low birth weight) were significantly associated with increased risk of ID.

Conclusion

This systemic review and meta-analysis provides a comprehensive evidence-based assessment of the risk factors for ID. Future studies are encouraged to focus on perinatal and neonatal risk factors and the combined effects of multiple factors.

Introduction

Intellectual disability (ID) or mental retardation (MR) is a developmental disability characterized by significant limitations in both intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior. Its onset occurs before 18 years of age[1], and its prevalence in the general population has been estimated at more than 1/100[2]. ID can be classified as genetic or non-genetic depending on its etiology. The causes of genetic ID, which accounts for only 30% to 50% of all ID cases[3], include chromosomal abnormalities (e.g. trisomy 21 syndrome), inherited genetic traits (e.g. fragile X syndrome) and single gene disorders (e.g. Prader—Willi syndrome)[4, 5]. However, the causes of non-genetic ID are not fully known. It is now suggested that the risk factors for non-genetic ID are extensive, and can be classified as prenatal, perinatal and neonatal factors according to the timing of suffering.

Numerous population-based studies have focused on specific non-genetic exposures as possible risk factors for ID. Many support the hypothesis that some prenatal (e.g. increasing maternal age, multiple gestation and maternal hypertension), perinatal (e.g. preterm birth and fetal distress) and neonatal (e.g. male sex, low birth weight and neonatal infection) exposures may increase the risk of ID[6, 7]. However, the overall conclusions of these studies are inconsistent. For example, some studies found that maternal hypertension increased the risk of ID[8, 9], whereas others did not[10–12]. The aim of the present study was to perform a meta-analysis of all pertinent available data to determine whether prenatal, perinatal, and neonatal exposures affect the onset of ID.

Material and Methods

Study identification and selection

The study was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses criteria (PRISMA) as shown in S1 File. The PubMed and Embase databases were searched using following keywords and subject terms: “intellectual disability”, “mental retardation”, “ID”, “MR” in combination with “prenatal”, “pregnancy”, “obstetric”, “perinatal”, “neonatal”. The last search was updated on September 15, 2015. There was no language restriction. All studies were initially screened by reading the titles and abstracts, and the full-texts of potential studies were independently assessed for eligibility by two reviewers (Jichong Huang and Tingting Zhu), who discussed disagreements to reach a consensus.

To be included in our analysis, the study had to: (1) evaluate the association between prenatal, perinatal, or neonatal factors and risk of ID, (2) have a cohort, case-control, or cross-sectional design, and (3) report odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) or other usable data. Studies were excluded if they: (1) did not eliminate the impact of genetic causes (e.g,. trisomy 21 syndrome, Prader-Willi syndrome and fragile X syndrome) on the risk of ID, (2) did not include a control group, or (3) overlapped with another study.

Data extraction

The following data were independently collected by two reviewers (Jichong Huang and Tingting Zhu) from each of the included studies: name of the first author, year of publication, the country in which the study was conducted, study design, age at diagnosis, total number of cases and controls, exposure assessment methods, outcome assessment methods, ID diagnostic criteria, and risk factors.

We only included risk factors that were evaluated in two or more studies. For each risk factor, we extracted the OR together with the 95% CI. When the OR was not provided in the study, we computed a crude OR.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of each included study was independently assessed by two reviewers (Jichong Huang and Tingting Zhu) using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS)[13, 14]. The quality score was evaluated based on three categories: group selection (four items), comparability between groups (one item), and outcome and exposure assessment (three items). And the maximum score was nine points. Studies were considered to be of high quality if they were scored above the median (> five points). Disagreements between the two reviewers were discussed until a consensus was reached.

Statistical analysis

A separate meta-analysis was conducted for each risk factor and the pooled OR was calculated by using the fixed-effects model (a P-value >0.10 indicated heterogeneity) or the random-effects model (a P-value <0.10 indicated heterogeneity) [15, 16]. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed by using the chi-square and I2 tests. Data were considered statistically heterogeneous if I2 >50% and P was <0.1. Publication bias was assessed by conducting tests for funnel plot asymmetry[17]. Begg’s test[18] and Egger’s test[19] were also used to assess publication bias. The statistical tests were performed by using Review Manager 5.3 and STATA 12.0 software.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

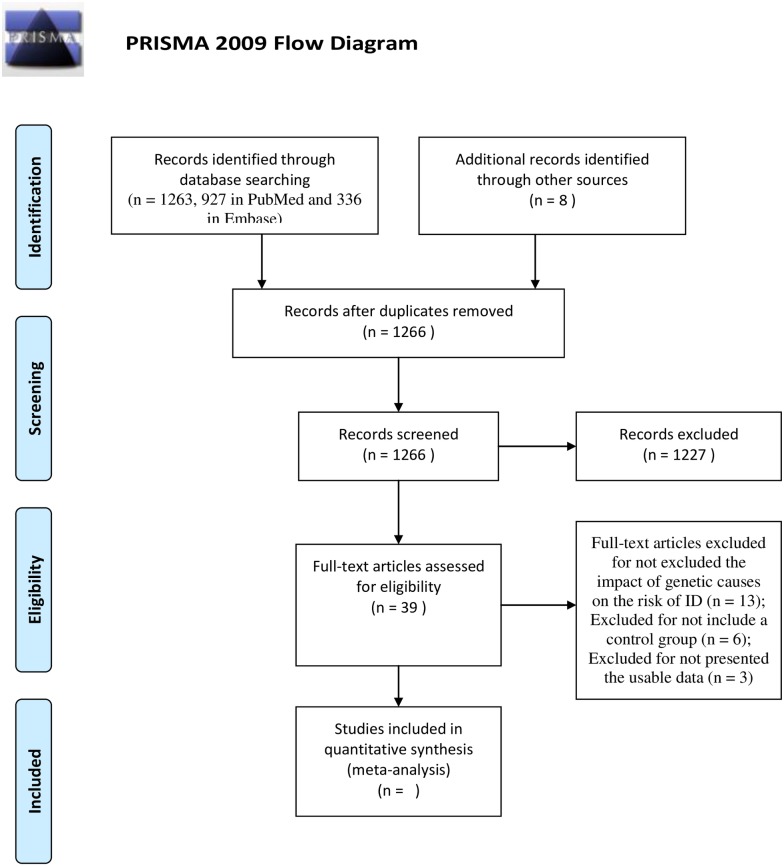

A total of 1,263 studies (927 in PubMed and 336 in Embase) and an additional eight studies culled from other sources were identified after an initial search. After reading the titles and abstracts, 1227 studies were excluded for irrelevant to the prenatal, perinatal or neonatal factors and ID risk, and five studies were excluded because of duplication. After reading the full-texts of the remaining 39 studies, 22 studies were excluded because they did not assess the effect of genetic causes on the risk of ID (13 studies), did not include a control group (six studies), or lacked usable data (three studies). Consequently, our analysis ultimately included 17 studies with a total of 55,344 patients and 5,723,749 control individuals. The meta-analysis included 15 risk factors (12 prenatal, one perinatal, and two neonatal). The selection process is shown in Fig 1, and the characteristics of each included study are presented in Table 1.

Fig 1. Flow gram of study selection process.

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies in meta-analysis.

| First author | Year | Country | Number(case/control) | Age of diagnosis | Study design | Exposure assessment | Outcome assessment | ID diagnostic criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Onicescu, G[20] | 2014 | USA | 420/6859 | 6–11 | Retrospective cohort study | Medical Record | Medical and school records | ICD9 |

| Mann, JR[21] | 2013 | USA | 3113/75562 | 3–6 | Retrospective cohort study | Medical Record | Registration data | ICD9 |

| Bilder, DA[11] | 2013 | USA | 146/16936 | 8 | Case-control study | Birth Certificate | School and health records | ICD9 |

| O'Leary, C [22](Non-Aboriginal births) | 2013 | Australia | 10576/30744 | 0–6 | Retrospective cohort study | Medical record | Registration data | DSM-IV |

| O'Leary, C [22](Aboriginal births) | 2013 | Australia | 7760/15762 | 0–6 | Retrospective cohort study | Medical record | Registration data | DSM-IV |

| Langridge, AT[8] | 2013 | Australia | 4576/376539 | 0–6 | Retrospective cohort study | Medical Record; Birth Certificate | Registration data | DSM-IIIR/ IV/ IV-TR |

| Griffith, MI[9] | 2011 | USA | 1636/79230 | 5–11 | Retrospective cohort study | Medical Record; Birth Certificate | Registration data | ICD9 |

| Mann, JR[10] | 2012 | USA | 5780/159531 | 3–6 | Retrospective cohort study | Medical Record; Birth Certificate | Registration data | ICD9 |

| Mann, JR[23] | 2009 | USA | 5388/129208 | 2–12 | Retrospective cohort study | Medical Record; Birth Certificate | Registration data | ICD9 |

| Leonard, H[12] | 2006 | Australia | 2674/236964 | 7–16 | Retrospective cohort study | Medical record | Registration data | DSM-IV |

| Croen, LA[24] | 2001 | USA | 11114/4590333 | 0–12 | Retrospective cohort study | Birth Certificate | Registration data | ICD9 |

| Drews, CD[25] | 1996 | USA | 221/400 | 10 | Case-control study | Children's mother report | Registration data;School and health records | IQ≤70 |

| Drews, CD[26] | 1995 | USA | 316/563 | 10 | Case-control study | Birth Certificate | Registration data;School and health records | IQ≤70 |

| Decoufle, F[27] | 1995 | USA | 314/562 | 10 | Case-control study | Birth Certificate | Registration data;School and health records | IQ≤70 |

| Yeargin-Allsopp, M[28] | 1995 | USA | 330/563 | 10 | Case-control study | Birth Certificate | Registration data;School and health records | IQ≤70 |

| McDermott, S[29] | 1993 | USA | 195/3098 | 5/9-10 | Case-control study | Cildren's mother report | Registration data | Raven Progressive Matrices score≤70 |

| Roeleveld, N[30] | 1992 | Netherlands | 306/322 | 0–15 | Case-control study | Medical Record | Medicaid Record;Registration data | ICD |

Abbreviation:

ICD, International Classification of Diseases;

DSM: The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders;

IQ, Intelligence Quotient.

Quality of the included studies

The methodological quality scores of the included studies ranged from four to seven points. The appraisal details are presented in S1 and S2 Tables. Ten of the 17 studies had scores of more than five points and were considered high quality. Variations in methodological quality may reflect in part the disproportionate inclusion of low-income families in some cohort studies[9, 10, 21, 23, 24] owing to the participation of these families in health insurance programs; consequently, middle- and upper-income families may have been underrepresented. In some case-control studies[25–29, 31], ID was only defined as intelligence quotient (IQ) ≤70, rather than via the diagnostic criteria of the International Classification of Diseases or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Moreover, because ID can begin before the age of 18 years, the follow-up time was insufficient in most cohort studies.

Prenatal, perinatal and neonatal risk factors

Tables 2–4 list the prenatal, perinatal, and neonatal risk factors included in the meta-analysis, as well as the summary effect estimate (ORs) with 95% CI and the P-value for each factor.

Table 2. Meta-analysis of prenatal risk factors for ID.

| Risk factor | Authors | No. of case/total | OR (95% CI) | P-value* | PHet |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilder 2013 | 29/2086 | ||||

| Mann 2012 | 209/3583 | ||||

| Advanced maternal age (≥35 vs.<35) | Mann 2009 | 51/2213 | 1.53(1.35, 1.72) | <0.001 | 0.03 |

| Croen 2001 | 1420/504751 | ||||

| Williams 1999 | 26/50 | ||||

| Drews 1996 | 32/112 | ||||

| Advanced maternal age (≥30 vs.<30) | Drews 1995 | NR | 0.81(0.62, 1.05) | 0.11 | 0.57 |

| Yeargin-Allsopp 1995 | 53/152 | ||||

| Bilder 2013 | 19/2266 | ||||

| Mann 2009 | 10/906 | ||||

| Maternal age<20 | Williams 1999 | 132/256 | 1.15(0.98, 1.35) | 0.09 | 0.2 |

| Drews 1996 | 60/129 | ||||

| Drews 1995 | NR | ||||

| Yeargin-Allsopp 1995 | 86/204 | ||||

| Onicescu 2014 | 1443/38204 | ||||

| Mann 2013 | 2892/81230 | ||||

| Mann 2012 | 321/4873 | ||||

| Maternal black race | Croen 2001 | 1650/367611 | 1.08(1.04, 1.13) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Williams 1999 | 356/624 | ||||

| Drews 1996 | 170/351 | ||||

| Drews 1995 | NR | ||||

| Yeargin-Allsopp 1995 | 232/499 | ||||

| Mann 2013 | 2399/60184 | ||||

| Mann 2012 | 1312/29950 | ||||

| Griffith 2011 | 749/31988 | ||||

| Mann 2009 | 2247/47540 | ||||

| Low maternal education (<12 vs.≥12 years) | Williams 1999 | 439/848 | 1.33(1.28, 1.37) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Drews 1996 | 121/198 | ||||

| Drews 1995 | NR | ||||

| Decoufle 1995 | 176/332 | ||||

| Yeargin-Allsopp 1995 | 177/333 |

*: Significant positive results (P<0.05).

NR, Not Report.

Table 4. Meta-analysis of peri- and neonatal risk factors for ID.

| Risk factor | Authors | No. of case/total | OR (95% CI) | P-value* | PHet |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preterm birth (GA<37 vs.≥37 weeks) | Bilder 2013 | 32/1359 | 2.03(1.79, 2.31) | <0.001 | 0.06 |

| Griffith 2011 | NR | ||||

| Onicescu 2014 | 284/3713 | ||||

| Langridge 2013 | NR | ||||

| Mann 2013 | 4028/83485 | ||||

| Mann 2012 | 2141/39669 | ||||

| Griffith 2011 | 1106/1174 | ||||

| Male sex | Croen 2001 | 7027/2350287 | 1.96(1.90, 2.01) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Mann 2009 | 3620/68610 | ||||

| Williams 1999 | 289/566 | ||||

| Drews 1996 | 138/333 | ||||

| Drews 1995 | NR | ||||

| Yeargin-Allsopp 1995 | 199/466 | ||||

| Bilder 2013 | 30/868 | ||||

| Griffith 2011 | 349/7667 | ||||

| Low birth weight (<2500g vs.≥2500g) | Croen 2001 | 8537/4314859 | 3.56(3.27, 3.89) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Drews 1996 | 39/73 | ||||

| McDermott 1993 | 195/3293 |

*: Significant positive results (P<0.05).

NR, Not Report.

The statistically significant prenatal risk factors identified in the meta-analysis were as follows: advanced maternal age (maternal age over 35) (OR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.21 to 1.96), maternal black race (OR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.33 to 2.20), low maternal education (OR, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.73 to 2.52), third or more parity (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.45 to 1.84), maternal alcohol use (OR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.30 to 1. 83), maternal tobacco use (OR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.06 to 1.15), maternal diabetes (OR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.00 to 1.41), maternal hypertension (OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.64), maternal epilepsy (OR, 2.63; 95% CI, 1.54 to 4.49) and maternal asthma (OR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.24 to 1.75) (Table 2). There was heterogeneity among the individual studies for most outcomes excepting those for third or more parity (I2 = 32%, P = 0.22), maternal tobacco use (I2 = 0%, P = 0.53), and maternal asthma (I2 = 0%, P = 0.75) (Table 2).

Significant positive associations were also found between ID risk and preterm birth (a prenatal factor) (OR, 2.50; 95% CI, 1.38 to 4.53) and between ID risk and two neonatal factors: male sex (OR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.64 to 2.07) and low birth weight (OR, 3.43; 95% CI, 2.25 to 5.32) (Table 3). Individual studies were heterogeneous for both neonatal outcomes (I2 = 93%, P <0.0001 for both) (Table 3).

Table 3. Meta-analysis of prenatal risk factors for ID (Continued).

| Risk factor | Authors | No. of case/total | OR (95% CI) | P-value* | PHet |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Croen 2001 | 3258/1412612 | ||||

| Parity = 2 (2 vs.1) | Drews 1996 | 71/236 | 1.11(0.96, 1.28) | 0.15 | 0.49 |

| Drews 1995 | NR | ||||

| Yeargin-Allsopp 1995 | 95/307 | ||||

| Croen 2001 | 4148/1347012 | ||||

| Parity≥3 (≥3 vs.1) | Drews 1996 | 79/158 | 1.63(1.45, 1.84) | <0.001 | 0.22 |

| Drews 1995 | NR | ||||

| Yeargin-Allsopp 1995 | 119/238 | ||||

| Onicescu 2014 | 8/85 | ||||

| O'leary 2013 (Non-Aboriginal births) | 265/676 | ||||

| Maternal alcohol use | O'leary 2013 (Aboriginal births) | 358/811 | 1.63(1.49, 1.78) | <0.001 | 0.02 |

| Mann 2009 | 68/1116 | ||||

| Drews 1996 | 39/104 | ||||

| Roeleveld 1992 | 204/383 | ||||

| Onicescu 2014 | 77/1180 | ||||

| Mann 2013 | 1177/30392 | ||||

| Bilder 2013 | 13/1389 | ||||

| Maternal tobacco use | Mann 2012 | 629/14503 | 1.10(1.06, 1.15) | <0.001 | 0.53 |

| Mann 2009 | 1089/27169 | ||||

| Drews 1996 | 221/400 | ||||

| Roeleveld 1992 | 154/308 | ||||

| Langridge 2013 | NR | ||||

| Maternal diabetes | Mann 2013 | 734/17988 | 1.15(1.08, 1.23) | <0.001 | 0.01 |

| Mann 2012 | 420/9784 | ||||

| Leonard 2006 | 47/2680 | ||||

| Bilder 2013 | 6/654 | ||||

| Langridge 2013 | NR | ||||

| Maternal hypertension /pre-eclampsia/eclampsia | Griffith 2011 | 155/5169 | 1.33(1.24, 1,42) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Mann 2012 | 523/11416 | ||||

| Leonard 2006 | 17/1379 | ||||

| Maternal epilepsy | Mann 2012 | 29/333 | 2.76(2.16, 3.52) | <0.001 | 0.03 |

| Leonard 2006 | 42/1147 | ||||

| Maternal asthma | Langridge 2013 | NR | 1.48(1.24, 1.75) | <0.001 | 0.75 |

| Leonard 2006 | 126/7743 |

*: Significant positive results (P<0.05).

NR, Not Report.

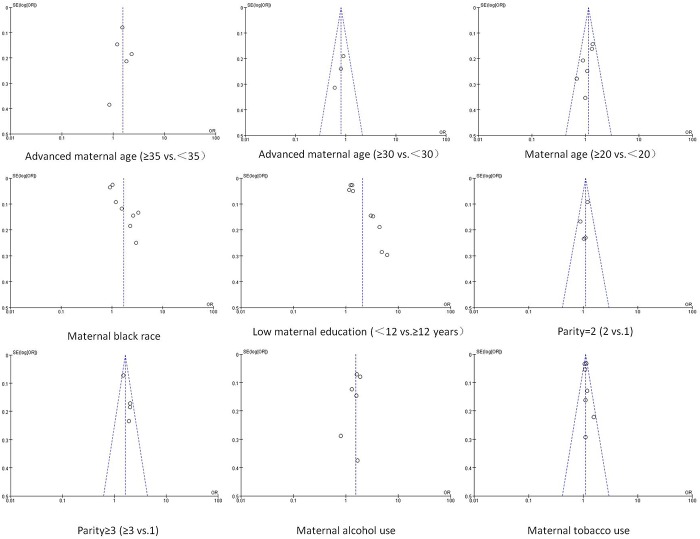

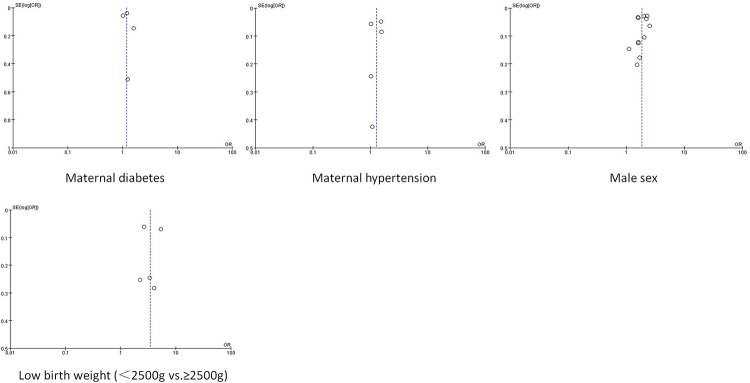

Publication bias

Publication bias was assessed for the factors examined in the pooled analysis of more than two studies (Figs 2 and 3). Significant publication bias was found for maternal black race (Begg’s test, P = 0.048; Egger’s test, P = 0.006) and low maternal education (Begg’s test, P = 0.022; Egger’s test, P <0.001).

Fig 2. Funnel plot for publication bias test.

The two oblique lines indicate the pseudo 95% confidence limits.

Fig 3. Funnel plot for publication bias test (Continued).

The two oblique lines indicate the pseudo 95% confidence limits.

Discussion

Identifying patients with a high risk of non-genetic ID is important for early detection and intervention of ID, which would benefit both clinical practice and public health. To our knowledge, this study is the first systemic review and meta-analysis of the relationship between prenatal, perinatal, and neonatal factors and the risk of ID. This meta-analysis included 17 cohort or case-control studies with a total of 55,344 patients and 5,723,749 control individuals.

The factors strongly associated with ID risk were advanced maternal age (>35 years), maternal black race, low maternal education, third or more parity, maternal alcohol use, maternal epilepsy, preterm birth, male sex, and low birth weight. Other significant factors with a lower strength of association (risk estimates less than 1.5) were maternal tobacco use, maternal diabetes, maternal hypertension and maternal asthma.

The fetus is highly susceptible to changes in maternal conditions. Risk factors such as maternal toxicant exposure and metabolic disorders can significantly affect the genetically programmed brain development of the fetus. Previous studies have shown that maternal tobacco exposure[32], alcohol exposure[33], diabetes[34] and hypertension[35] can result in abnormal brain development. These risk factors are therefore closely associated with intelligence development, as indicated by our meta-analysis. What’s more, Mann et al. have demonstrated that pre-pregnancy obesity contributes to maternal metabolic disorders, and is also associated with significantly increased risk of ID in the children[21]. Therefore, more epidemiological studies in a variety of geographic groups are needed in the future to test the consistency and generalisability of this association.

Before the 21st century, advanced maternal age was considered to be >30 years. Several studies during that period investigated but could not confirm a relationship between maternal age and risk of ID owing to insignificant results[25, 26, 28]. In recent years, the maternal age at delivery has increased, and advanced maternal age has been redefined as >35 years. Our meta-analysis demonstrates a positive association between maternal age >35 years and the risk of ID. The father’s age at the time the of child’s birth is also increasing, and has been shown to correlate with ID risk[30]. However, most studies in our meta-analysis did not exclude the potential effects of this confounder. Further well-adjusted studies are needed and should explore the other cut-off criteria besides age over 35-year-old.

There were no significant associations between ID risk and young maternal age (under 20-year-old) or second parity. The reason may be the limited number of included studies and insufficient simple size. Young maternal age often indicates a low education level, which is also related to ID risk. However, some of the studies included in our meta-analysis did not control this confounder. Moreover, since young maternal age ranges from 16 to 20 years old[36, 37], a more extensive age range should be taken into consideration in future investigations of ID risk.

Two previous meta-analyses examined the relationship between IQ score and preterm birth[38, 39]. Both reported significantly lower IQ scores in preterm as compared with full-term infants, which is consistent with our results. In addition, Kerr-Wilson et al. reported a linear dose-response relationship between the IQ score and the gestation period: the IQ score decreased steadily for each 1-week decrease in the gestation period[38]. Similarly, it is worthwhile to determine whether this relationship exists even in ID cases with different severity levels. Therefore, further studies should be performed to investigate the associations between different gestational weeks and the severity of ID in preterm infants.

Some limitations of this meta-analysis should be addressed. First, several studies presented only crude ORs and did not adjust for other potential confounders, which might have resulted in overestimation of the association between risk factors and ID. Second, the heterogeneity among studies was noted in most risk factors. This heterogeneity resulted from the different diagnostic criteria of ID, age of diagnosis, sample size, and exposure or outcome assessment methods among studies. Moreover, the number of studies in each meta-analysis limited our ability to investigate these factors. Third, only published data were included in this analysis.

Conclusions

This systemic review and meta-analysis identified prenatal, perinatal and neonatal risk factors for ID. The findings of this study indicate that prenatal factors have been the focus for studies on ID risk. In the future, more studies that focus on perinatal and neonatal factors are required, and researchers should be encouraged to investigate combinations of factors to a further study on the mechanisms leading to ID.

Supporting Information

(DOC)

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (No.81330016, 81300524, 81172174, 81270724 and 81200462), grants from the State Commission of Science Technology of China (2013CB967404, 2012BAI04B04), grants from the Ministry of Education of China (IRT0935, 313037), grants from the Science and Technology Bureau of Sichuan province (2014SZ0149), and a grant of clinical discipline program (neonatology) from the Ministry of Health of China (1311200003303).

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (No. 81330016, 81300524, 81172174, 81270724 and 81200462), grants from the State Commission of Science Technology of China (2013CB967404, 2012BAI04B04), grants from the Ministry of Education of China (IRT0935, 313037), grants from the Science and Technology Bureau of Sichuan province (2014SZ0149, 2016TD0002), and a grant of clinical discipline program (neonatology) from the Ministry of Health of China (1311200003303).

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV Washington, DC.

- 2.Maulik PK, Mascarenhas MN, Mathers CD, Dua T, Saxena S. Prevalence of intellectual disability: a meta-analysis of population-based studies. Research in developmental disabilities. 2011;32(2):419–36. 10.1016/j.ridd.2010.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curry CJ, Stevenson RE, Aughton D, Byrne J, Carey JC, Cassidy S, et al. Evaluation of mental retardation: recommendations of a Consensus Conference: American College of Medical Genetics. American journal of medical genetics. 1997;72(4):468–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaufman L, Ayub M, Vincent JB. The genetic basis of non-syndromic intellectual disability: a review. Journal of neurodevelopmental disorders. 2010;2(4):182–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rauch A, Hoyer J, Guth S, Zweier C, Kraus C, Becker C, et al. Diagnostic yield of various genetic approaches in patients with unexplained developmental delay or mental retardation. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140A(19):2063–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lyall K, Pauls DL, Santangelo S, Spiegelman D, Ascherio A. Maternal Early Life Factors Associated with Hormone Levels and the Risk of Having a Child with an Autism Spectrum Disorder in the Nurses Health Study II. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41(5):618–27. 10.1007/s10803-010-1079-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDermott S, Durkin MS, Schupf N, Stein Z. Epidemiology and etiology of mental retardation In: Jacobson JW, Mulick JA, Rojahn J, editors. Handbook of Intellectual Disabilities and Developmental Disabilities New York: Springer Press; 2007: p. 3–40. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langridge AT, Glasson EJ, Nassar N, Jacoby P, Pennell C, Hagan R, et al. Maternal conditions and perinatal characteristics associated with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. PloS one. 2013;8(1):e50963 10.1371/journal.pone.0050963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffith MI, Mann JR, McDermott S. The Risk of Intellectual Disability in Children Born to Mothers with Preeclampsia or Eclampsia with Partial Mediation by Low Birth Weight. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2011;30(1):108–15. 10.3109/10641955.2010.507837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mann JR, Pan C, Rao GA, McDermott S, Hardin JW. Children Born to Diabetic Mothers May be More Likely to Have Intellectual Disability. Matern Child Hlth J. 2013;17(5):928–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bilder DA, Pinborough-Zimmerman J, Bakian AV, Miller JS, Dorius JT, Nangle B, et al. Prenatal and perinatal factors associated with intellectual disability. American journal on intellectual and developmental disabilities. 2013;118(2):156–76. 10.1352/1944-7558-118.2.156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leonard H, De Klerk N, Bourke J, Bower C. Maternal health in pregnancy and intellectual disability in the offspring: A population-based study. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(6):448–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.GA Wells BS, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa score for non-randomized studies. Available: http://wwwohrica Accessed November, 2015. 2015.

- 14.Elyasi M, Abreu LG, Badri P, Saltaji H, Flores-Mir C, Amin M. Impact of Sense of Coherence on Oral Health Behaviors: A Systematic Review. PloS one. 2015;10(8):e0133918 10.1371/journal.pone.0133918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled clinical trials. 1986;7(3):177–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takkouche B, Cadarso-Suarez C, Spiegelman D. Evaluation of old and new tests of heterogeneity in epidemiologic meta-analysis. American journal of epidemiology. 1999;150(2):206–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khoshdel A, Attia J, Carney SL. Basic concepts in meta-analysis: A primer for clinicians. International journal of clinical practice. 2006;60(10):1287–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj. 1997;315(7109):629–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Onicescu G, Lawson AB, McDermott S, Aelion CM, Cai B. Bayesian importance parameter modeling of misaligned predictors: soil metal measures related to residential history and intellectual disability in children. Environmental science and pollution research international. 2014;21(18):10775–86. 10.1007/s11356-014-3072-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mann JR, McDermott SW, Hardin J, Pan C, Zhang Z. Pre-pregnancy body mass index, weight change during pregnancy, and risk of intellectual disability in children. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2013;120(3):309–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Leary C, Leonard H, Bourke J, D'Antoine H, Bartu A, Bower C. Intellectual disability: population-based estimates of the proportion attributable to maternal alcohol use disorder during pregnancy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55(3):271–7. 10.1111/dmcn.12029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mann JR, Mcdermott S, Barnes TL, Hardin J, Bao HK, Zhou L. Trichomoniasis in Pregnancy and Mental Retardation in Children. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19(12):891–9. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Croen LA, Grether JK, Selvin S. The epidemiology of mental retardation of unknown cause. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):art. no.-e86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drews CD, Murphy CC, YearginAllsopp M, Decoufle P. The relationship between idiopathic mental retardation and maternal smoking during pregnancy. Pediatrics. 1996;97(4):547–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drews CD, Yearginallsopp M, Decoufle P, Murphy CC. Variation In the Influence Of Selected Sociodemographic Risk-Factors for Mental-Retardation. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(3):329–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Decoufle F, Boyle CA. The relationship between maternal education and mental retardation in 10-year-old children. Ann Epidemiol. 1995(5):347–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yearginallsopp M, Drews CD, Decoufle P, Murphy CC. Mild Mental-Retardation In Black-And-White Children In Metropolitan Atlanta—a Case-Control Study. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(3):324–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDermott S, Cokert AL, McKeown RE. Low birthweight and risk of mild mental retardation by ages 5 and 9 to 11. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology. 1993;7(2):195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roeleveld N, Vingerhoets E, Zielhuis GA, Gabreels F. Mental-Retardation Associated with Parental Smoking And Alcohol-Consumption before, during, And after Pregnancy. Prev Med. 1992;21(1):110–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams LO, Decoufle P. Is maternal age a risk factor for mental retardation among children? American journal of epidemiology. 1999;149(9):814–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ekblad M, Korkeila J, Lehtonen L. Smoking during pregnancy affects foetal brain development. Acta paediatrica. 2015;104(1):12–8. 10.1111/apa.12791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson JE, Ebrahim S, Floyd L, Atrash H. Prevalence of risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes during pregnancy and the preconception period—United States, 2002–2004. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10(5 Suppl):S101–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hagberg H, Gressens P, Mallard C. Inflammation during fetal and neonatal life: implications for neurologic and neuropsychiatric disease in children and adults. Annals of neurology. 2012;71(4):444–57. 10.1002/ana.22620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robinson M, Mattes E, Oddy WH, de Klerk NH, Li J, McLean NJ, et al. Hypertensive Diseases of Pregnancy and the Development of Behavioral Problems in Childhood and Adolescence: The Western Australian Pregnancy Cohort Study. J Pediatr-Us. 2009;154(2):218–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rindfuss RR, Morgan SP, Offutt K. Education and the changing age pattern of American fertility: 1963–1989. Demography. 1996;33(3):277–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams MM, Bruce FC, Shulman HB, Kendrick JS, Brogan DJ. Pregnancy planning and pre-conception counseling. The PRAMS Working Group. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1993;82(6):955–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kerr-Wilson CO, Mackay DF, Smith GC, Pell JP. Meta-analysis of the association between preterm delivery and intelligence. Journal of public health. 2012;34(2):209–16. 10.1093/pubmed/fdr024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhutta AT, Cleves MA, Casey PH, Cradock MM, Anand KJ. Cognitive and behavioral outcomes of school-aged children who were born preterm: a meta-analysis. Jama. 2002;288(6):728–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC)

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.