Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the care and outcomes of patients with TIA or minor stroke admitted to the hospital vs discharged from the emergency department (ED).

Methods:

We used the Ontario Stroke Registry to create a cohort of patients with minor ischemic stroke/TIA who presented to the hospital April 1, 2008, to March 31, 2009, or April 1, 2010, to March 31, 2011, in the province of Ontario, Canada. We compared processes of care and outcomes (death or recurrent stroke/TIA) in patients admitted to the hospital and discharged with and without stroke prevention clinic follow-up.

Results:

In our sample of 8,540 patients, the use of recommended interventions was highest in admitted patients, followed by discharged patients referred to prevention clinics, followed by those discharged without clinic referral. Eight percent of nonadmitted patients returned to the hospital with recurrent stroke/TIA within 1 week of the index event. One-year stroke case-fatality was similar in admitted and discharged patients (adjusted hazard ratio 1.11; 95% confidence interval 0.92–1.34). Among patients discharged from EDs, referral to a stroke prevention clinic was associated with a markedly lower risk of mortality (adjusted hazard ratio 0.49; 95% confidence interval 0.38–0.64).

Conclusions:

Patients with minor ischemic stroke or TIA discharged from the ED are less likely than admitted patients to receive timely stroke care interventions. Among discharged patients, referral to a stroke prevention clinic is associated with improved processes of care and lower mortality. Additional strategies are needed to improve access to high-quality outpatient TIA care.

TIA carries a substantial risk of subsequent stroke, at approximately 10% to 20% within 90 days of the index TIA, and with half of recurrent events occurring within the first 2 days.1 Stroke risk following TIA varies depending on the underlying mechanism of vascular disease, as well as the presence or absence of comorbid conditions and initial presenting symptoms.2,3

Guidelines recommend that patients with TIA and minor ischemic stroke undergo rapid screening for significant symptomatic carotid artery stenosis, identification and management of risk factors including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and atrial fibrillation, and initiation of antithrombotic therapy.4,5 Previous research has found that patients with TIA have low rates of recommended investigations and interventions compared to those with stroke6; however, these observations antedate the recognition of TIA as a high-risk condition, as well as the creation of stroke centers, rapid outpatient TIA clinics, and stroke prevention clinics. Observational studies have found that urgent outpatient management strategies are superior to usual ambulatory care for TIA and minor stroke; however, less is known about how such outpatient care compares to hospitalization.7–17

We used data from a clinical stroke registry in Ontario, Canada, linked with administrative databases, to compare the care and outcomes of patients with TIA and minor ischemic stroke admitted to the hospital and discharged from the emergency department (ED), and in those referred and not referred to stroke prevention clinics after discharge.

METHODS

Setting.

Ontario is Canada's most populous province, with a population of approximately 12.6 million, more than 150 acute care hospitals, and an established system of regionalized stroke care delivery.18 Provincial residents have universal access to hospital care, physicians' services, and diagnostic testing, and residents older than 65 years have universal access to prescription medications covered by the provincial drug formulary. We conducted a cohort study of Ontarians with TIA (defined as transient focal neurologic symptoms of less than 24 hours' duration, with no evidence of infarction on neuroimaging) or minor ischemic stroke (defined as a Canadian Neurological Scale score greater than 10 at the time of initial assessment in ED, corresponding to an NIH Stroke Scale score of less than 3) seen in the ED of any Ontario hospital and included in the Ontario Stroke Registry.

Data sources and study sample.

The Ontario Stroke Registry (formerly known as the Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network/RCSN) performs periodic audits to collect detailed information about the ED and in-hospital care of individuals with acute stroke or TIA seen at all 150 acute care institutions in the province. Validation by duplicate chart abstraction has shown excellent agreement for key variables including stroke type and admission to the hospital.19

The registry is housed at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences where it is linked to population-based administrative databases using unique encoded patient identifiers. We used the Discharge Abstract Database and the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System databases maintained by the Canadian Institute for Health Information to identify recurrent admissions and ED visits for stroke or TIA, using the ICD-10-CA codes I60, I61, I63, I64, and G45 in the primary diagnosis position. We used the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System database to identify times of ED overcrowding, defined as a mean length of stay in the ED of greater than 4 hours for patients of similar acuity seen in the ED on the same shift as the index patient.20 We used the Ontario Registered Persons Database to identify all-cause mortality, the Office of the Registrar General deaths database to identify the underlying cause of death, the Ontario Health Insurance Plan database to identify procedures performed following hospital discharge, the Ontario Drug Benefits database to identify medication claims for patients older than 65 years, and the 2010 Canada Census to provide information on socioeconomic status based on median neighborhood income for each patient. These databases are validated and routinely used for health services research.21

For the present study, we included all patients with TIA or minor ischemic stroke who were aged 18 years or older and who were seen in the ED or admitted to the hospital between April 1, 2008, and March 31, 2009, or April 1, 2010, and March 31, 2011. Although registry data were available dating back to 2001, we selected this particular study period in order to evaluate the contemporary management of patients with TIA and minor stroke. For patients with more than one event during the study time frame, only the first event was included.

Stroke prevention clinics.

In 2001, the provincial government established a network of designated stroke prevention clinics, with the goal of coordinating testing and treatment for high-risk patients with stroke and TIA. Currently, there are 43 stroke prevention clinics, with the majority located in designated stroke centers, operating 3 to 5 days per week with no weekend availability. Although Canadian clinical practice guidelines recommend that patients with acute TIA or minor stroke who are not admitted to the hospital be referred to a stroke prevention clinic, standardized referral and triage algorithms were not in place in all sites at the time of this study.22 In an audit of stroke prevention clinics performed in 2011, the median time from referral to clinic visit ranged from 6 days for emergent cases to 23 days for elective cases.22

Outcomes.

We evaluated the following processes of stroke care: (1) brain imaging (either CT or MRI) within 7 days of the index event; (2) carotid imaging (with carotid Doppler ultrasound, or CT, magnetic resonance, or catheter angiography) within 48 hours of the index event; (3) screening for cardiac arrhythmias with telemetry or other ambulatory cardiac rhythm monitoring within 30 days of the index event; (4) echocardiography within 30 days of the index event; (5) antithrombotic therapy (antiplatelet or oral anticoagulants) at discharge; (6) oral anticoagulation at discharge in the subgroup with atrial fibrillation; (7) antihypertensive and lipid-lowering therapy within 30 days of discharge (in the subgroup of patients older than 65 years); (8) carotid revascularization within 14 days of the index event; and (9) consultation by a neurologist in the ED or during hospitalization. We also evaluated the outcomes of death, death due to cardiovascular disease (stroke, myocardial infarction, or congestive heart failure), and recurrent stroke or TIA resulting in an ED visit or hospitalization within 1 year of the index event. For hospitalized patients, we evaluated the proportion who experienced a new stroke/TIA or neurologic worsening during admission; however, because information on the timing of these events was not available, we could not include these events in the analyses comparing admitted and discharged patients.

Analysis.

We compared baseline characteristics, processes of care, and outcomes among 3 groups of patients: those admitted to the hospital from the ED, those discharged from the ED with referral to a stroke prevention clinic, and those discharged from the ED with no referral. We used χ2 tests for categorical variables and 1-way analysis of variance for continuous variables. Secondary analyses were performed in the subgroups with TIA alone and minor ischemic stroke alone, and in the subset of patients seen at hospitals with a designated stroke prevention clinic on-site.

We then compared the outcomes of death and recurrent stroke/TIA in patients who were admitted to the hospital vs discharged from the ED. We used Cox proportional hazard models to determine the effect of admission on the hazard of death, with adjustment for the following: (1) patient characteristics (age, sex, residence before admission, rural residence, neighborhood income group, prestroke functional status, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, smoking, atrial fibrillation, and coronary artery disease); (2) characteristics of the index event (motor or speech deficits, duration of symptoms, ABCD2 score2); (3) characteristics of the care encounter (ED overcrowding, presentation off-hours); and (4) hospital characteristics (hospital size, peer group [regional stroke center/district stroke center/nondesignated hospital], availability of a stroke unit, presence of a stroke prevention clinic on-site, and number of days of operation of the clinic) and region of care, based on Ontario's 14 local health integration networks. A robust, sandwich-type variance estimator was used to account for the clustering of patients with hospitals. For the outcome of stroke/TIA, we estimated the incidence of stroke/TIA as a function of time in admitted vs discharged patients using cumulative incidence functions to account for the competing risk of death,23 and Cox proportional hazard models to estimate the effect of admission on the cause-specific hazard of stroke/TIA (i.e., the rate of occurrence of stroke/TIA in those who are currently event-free) with adjustment for the same predictor variables listed above.

We repeated the above analyses to compare outcomes in patients discharged from the ED who were referred to a stroke prevention clinic and discharged patients who were not referred to such a clinic. We used referral rather than an actual assessment at a clinic as the exposure variable, in order to avoid survival-treatment bias, because early mortality would have precluded assessment in clinic. Since patients referred to stroke prevention clinics are likely to be systematically different from those who are not, we performed secondary analyses in which we used inverse probability of treatment weighting using the propensity score to account for confounding due to measured baseline covariates.24 We used Cox proportional hazard models to estimate the effect of referral to a stroke prevention clinic on the hazard of death, using the stabilized weights to adjust for confounding. In the sample weighted by the stabilized weights, we computed standardized differences to assess the balance of measured baseline covariates between treatment groups. Finally, using the original unmatched cohort, we used χ2 tests to compare the proportions of patients who were discharged with and without clinic referral who died due to cardiovascular disease vs other causes.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

Data collection for the registry is done without patient consent, since the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences is named as a prescribed entity under provincial privacy legislation. The study was approved by the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre Research Ethics Board.

RESULTS

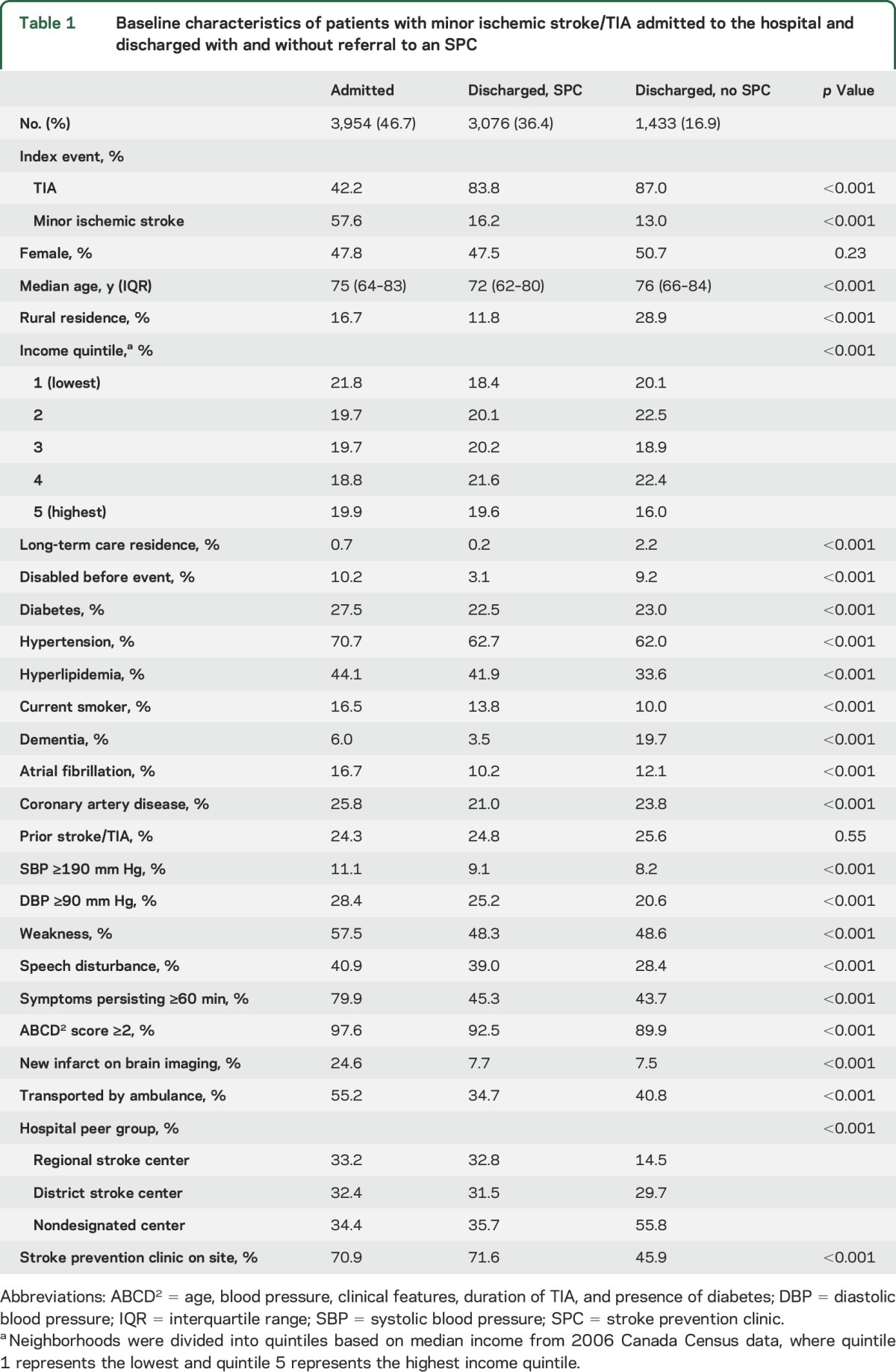

The study sample consisted of 8,540 patients seen in the ED with TIA or minor ischemic stroke. Overall, 3,954 patients (46.7%) were admitted to the hospital. The baseline characteristics of participants are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with minor ischemic stroke/TIA admitted to the hospital and discharged with and without referral to an SPC

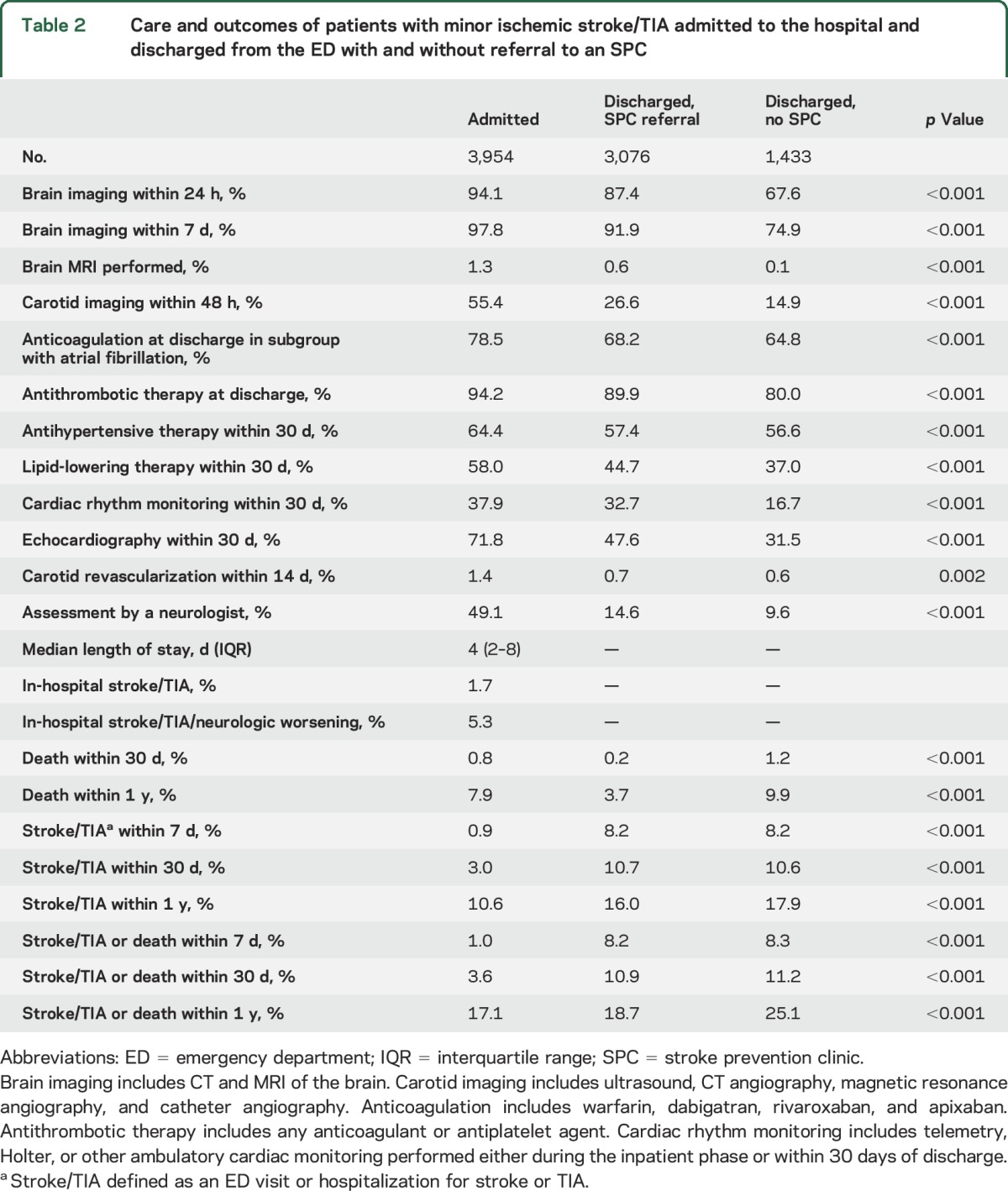

The use of brain and carotid imaging, cardiac rhythm monitoring, echocardiography, consultations by neurologists, and medications for secondary stroke prevention were highest in admitted patients, followed by discharged patients referred to prevention clinics, followed by those discharged without clinic referral (table 2). The proportion who died within 1 year of the index event was 7.9% of those admitted to the hospital, 3.7% of those discharged from the ED with a stroke clinic referral, and 9.9% of those discharged without such a referral (p < 0.001) (table 2). The proportion with a repeat ED visit or hospitalization for stroke/TIA within 7 days was 0.9% of those admitted, 8.2% of those discharged with a stroke prevention clinic referral, and 8.3% of those discharged without a clinic referral (p < 0.001) (table 2). Results were similar in the subgroups with TIA alone and minor stroke alone, and in the subset of patients seen at hospitals where there was a designated stroke prevention clinic on-site (tables e-1 to e-3 on the Neurology® Web site at Neurology.org). Among admitted patients, the median length of stay was 4 days, 1.7% had a new stroke/TIA, and 5.3% experienced neurologic worsening or a new stroke/TIA.

Table 2.

Care and outcomes of patients with minor ischemic stroke/TIA admitted to the hospital and discharged from the ED with and without referral to an SPC

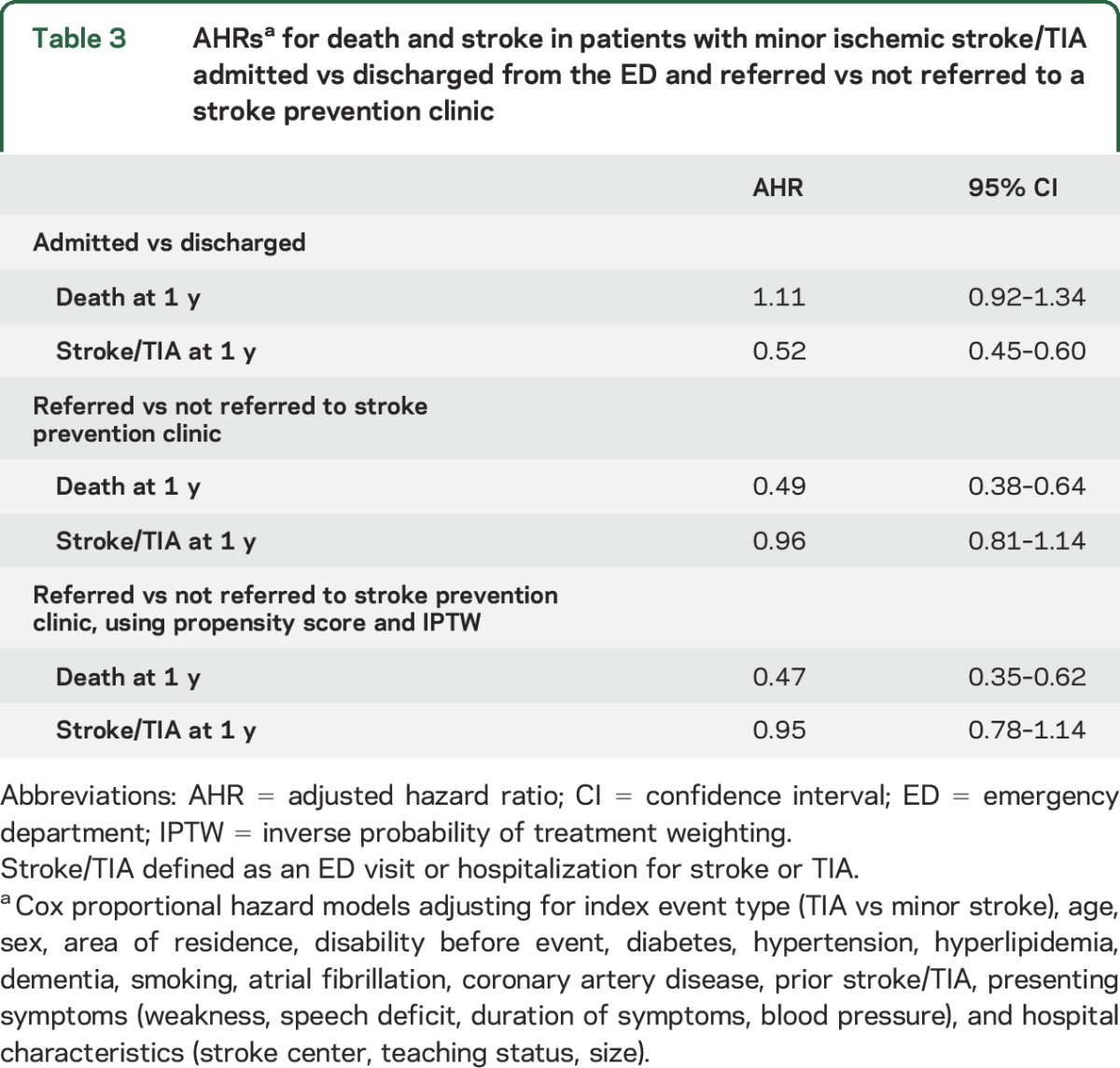

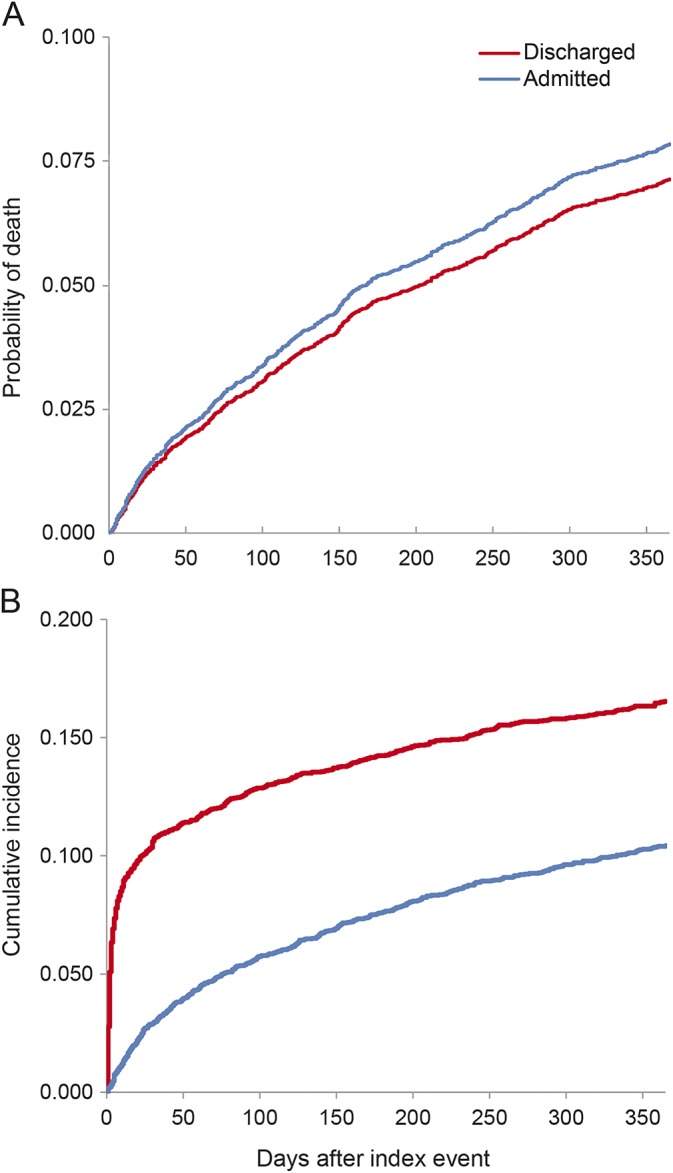

After adjustment for age, sex, comorbid conditions, and other factors in the multivariable analyses, the hazard of mortality in admitted patients was similar to that in discharged patients (adjusted hazard ratio [AHR] for admitted vs discharged patients 1.11; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.92–1.34), while the hazard of readmissions or repeat ED visits for stroke/TIA was lower in admitted vs discharged patients (AHR 0.52; 95% CI 0.45–0.60) (table 3 and figure 1, A and B).

Table 3.

AHRsa for death and stroke in patients with minor ischemic stroke/TIA admitted vs discharged from the ED and referred vs not referred to a stroke prevention clinic

Figure 1. Adjusted probability of death in admitted vs discharged patients with TIA or minor stroke and cumulative incidence of recurrent stroke/TIA in admitted vs discharged patients.

(A) Adjusted probability of death in patients with TIA or minor stroke admitted to the hospital or discharged from the emergency department. Adjusted for index event type (TIA vs minor stroke), age, sex, area of residence, disability before event, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, dementia, smoking, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, prior stroke/TIA, presenting symptoms (weakness, speech deficit, duration of symptoms, blood pressure), and hospital characteristics (stroke center, teaching status, size). The p value = 0.15 for difference between discharged and admitted patients, based on Cox proportional hazards model. (B) Cumulative incidence of recurrent stroke/TIA in admitted vs discharged patients. Cumulative incidence of recurrent emergency department visit or hospitalization for stroke/TIA within 1 year of the index event in patients with minor ischemic stroke/TIA admitted to the hospital vs discharged from the emergency department. Figures constructed using cumulative incidence functions that account for the competing risk of death. For difference between discharged and admitted patients, p < 0.001, using Gray's test for equality of cumulative incidence functions.

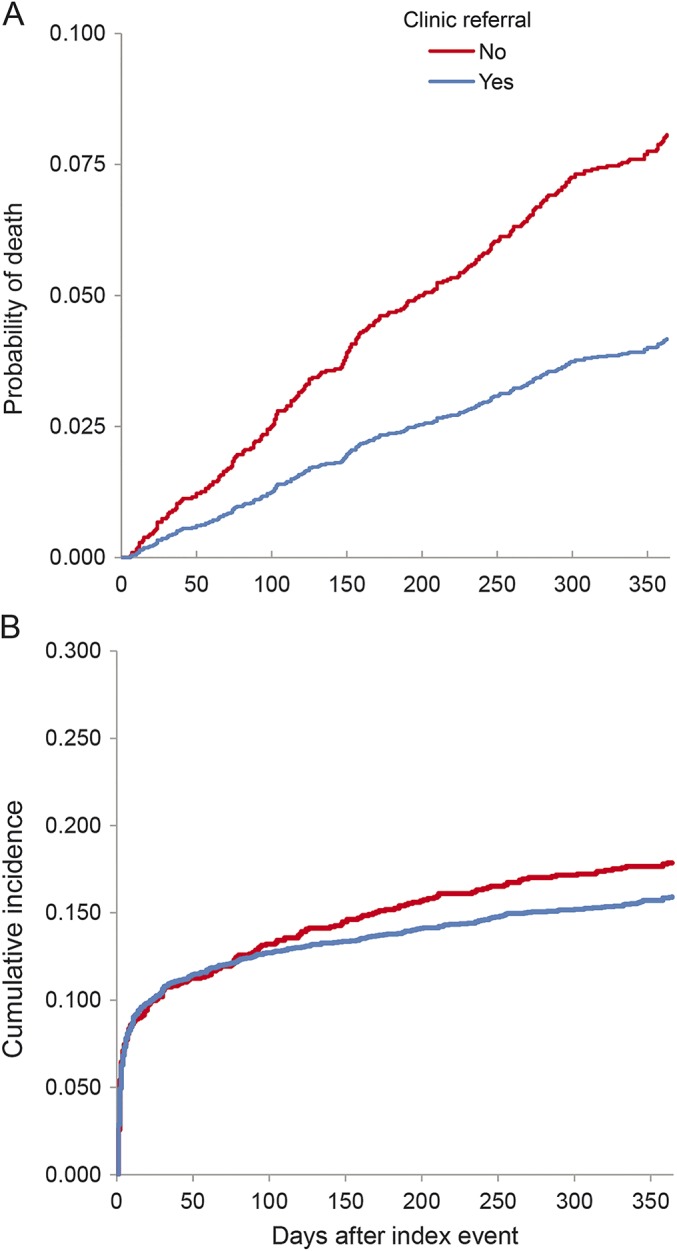

In the subgroup of patients discharged from the ED, the adjusted hazard of mortality was lower in those referred to stroke prevention clinics compared to those not referred (AHR 0.49; 95% CI 0.38–0.64) (table 3 and figure 2A), and results were similar when the analyses were performed using propensity score methods (table 3). Among patients who died within 1 year, the cause of death was cardiovascular disease (stroke, myocardial infarction, or congestive heart failure) in 22 of 114 patients referred to stroke prevention clinics (19%) vs 43 of 142 patients not referred (30%) (p = 0.045). The adjusted hazard of readmissions/ED visits for stroke/TIA was similar in discharged patients with and without a referral to a stroke prevention clinic (AHR 0.96; 95% CI 0.81–1.14) (table 3 and figure 2B).

Figure 2. Adjusted probability of death and cumulative incidence of stroke/TIA in patients referred and not referred to stroke prevention clinics.

(A) Adjusted probability of death in patients referred and not referred to stroke prevention clinics. Adjusted for index event type (TIA vs minor stroke), age, sex, area of residence, disability before event, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, dementia, smoking, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, prior stroke/TIA, presenting symptoms (weakness, speech deficit, duration of symptoms, blood pressure), and hospital characteristics (stroke center, teaching status, size). The p value is <0.001 for the difference between patients referred and not referred to stroke prevention clinics, based on Cox proportional hazards model. (B) Cumulative incidence of stroke/TIA in patients referred vs not referred to a stroke prevention clinic. Adjusted probability of death in patients referred and not referred to stroke prevention clinics. Adjusted for index event type (TIA vs minor stroke), age, sex, area of residence, disability before event, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, dementia, smoking, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, prior stroke/TIA, presenting symptoms (weakness, speech deficit, duration of symptoms, blood pressure), and hospital characteristics (stroke center, teaching status, size). For difference between patients referred and not referred to stroke prevention clinics, p < 0.001, based on Cox proportional hazards model.

DISCUSSION

In this population-based study, we found that patients with TIA or minor ischemic stroke who were discharged from the ED were much less likely than admitted patients to receive recommended tests and treatments, with fewer patients undergoing prompt brain imaging, carotid imaging, arrhythmia monitoring, and initiation of antithrombotic, antihypertensive, and lipid-lowering therapy. Referral to a stroke prevention clinic was associated with improved processes of care and decreased mortality.

The striking discrepancy in the quality of care between admitted and discharged patients is concerning in light of the high early risk of stroke following TIA and the improved outcomes that can be achieved with early investigation and treatment.9,12 Although hospitalization of all patients with TIA or minor ischemic stroke is neither feasible nor desirable, usual systems of outpatient care are unlikely to provide the rapid treatment required by this patient group.25,26 Same-day or next-day clinics, rapid evaluation units, and outpatient access to stroke teams are alternatives to hospitalization that have been studied in various jurisdictions and have been associated with improved outcomes compared to standard care.7,8,10,11,13–17,27,28 Although such urgent outpatient units have been established in other jurisdictions, these are currently not widely available in North America, and we could not include such units as a comparison group in our analyses. We found that patients with TIA or minor stroke referred to stroke prevention clinics had improved processes of care compared to those who were not referred; however, these still lagged behind what was provided during hospitalization. This likely reflects the current structure of Ontario's stroke prevention clinics, none of which operate on weekends or off-hours and which have a median waiting time of 6 days for evaluation of emergent patients.22 Although hospitalization does not prevent all recurrent events (1.7% of our hospitalized cohort experienced a new stroke and 5.3% experienced a new stroke or neurologic worsening), our finding that approximately 8% of those discharged from the ED either revisited an ED or were hospitalized for stroke or TIA within 7 days suggests that, to be effective, outpatient clinics should accommodate patients with minor stroke and TIA within the first week of presentation. New algorithms for the triage of patients with minor ischemic stroke and TIA might help clinics prioritize appointments for high-risk patients.29,30

Ontario has a well-established regional system of stroke care that includes provincial quality-improvement initiatives.18 In general, the quality of stroke care in the province is excellent, with the most recent audit from fiscal year 2012/2013 documenting province-wide use of brain imaging within 24 hours in 93%, carotid imaging in 82%, and antiplatelet therapy in 94% of patients.31 Thus, the low use of recommended tests and treatments in our cohort with minor stroke/TIA discharged from the ED falls well below provincial benchmarks and differs from the stroke care typically provided in the province. This suggests that targeted quality-improvement initiatives are needed to address gaps in care for this particular population.

We found lower mortality in discharged patients referred to stroke prevention clinics compared to those without such a referral, even after using both multivariable and propensity-matched analyses to adjust for differences in baseline characteristics, a finding that was also observed in a previous Ontario study using a different patient cohort that included admitted patients and those with more severe strokes.15 Although we found no differences in ED visits or hospitalizations for stroke/TIA in patients referred and not referred to stroke prevention clinics, mortality due to cardiovascular causes was lower in referred patients. Further research is needed to determine whether there is a true causal relationship between stroke prevention clinic care and reduced mortality after minor stroke or TIA, or whether our findings are attributable to patient selection and referral patterns.

Some limitations of our study warrant emphasis. Given the challenges in distinguishing TIA from stroke mimics in the ED setting, the lower use of tests and treatments in discharged patients may be partly attributable to a lower frequency of true stroke or TIA in this cohort. We only had information on whether a referral had been made to a stroke prevention clinic, and not on when or whether a visit occurred. However, using clinic referral rather than assessment as our exposure variable prevented survival-treatment bias. Although the Ontario Stroke Registry includes detailed information on baseline factors, there may have been unmeasured differences that accounted for some of the observed differences in outcomes among groups. Finally, our results were obtained in the context of an organized system of stroke care within a universal health care system and may not be generalizable to other settings or populations. Despite this, our findings from a large, province-wide sample of patients from every hospital, with detailed clinical information linked with administrative data to provide complete follow-up for deaths and readmissions, provide important insights into contemporary patterns of care of patients with TIA and minor stroke, and identify gaps in care that can be addressed through targeted interventions.

We found that patients with minor ischemic stroke and TIA who were discharged from the ED received lower quality of care than those who were admitted to the hospital and were at high risk of death and recurrent stroke. Stroke prevention clinic referral was associated with improved care and lower mortality after minor stroke and TIA. Future activities should focus on improving rapid access to appropriate outpatient care for patients who are not admitted to the hospital.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Mr. Brennan Rashkovan for his assistance in formatting tables and references for this manuscript and Dr. David Juurlink for helpful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript.

GLOSSARY

- ABCD2

age, blood pressure, clinical features, duration of TIA, and presence of diabetes

- AHR

adjusted hazard ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- ED

emergency department

- ICD-10-CA

International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Canada

Footnotes

Editorial, page 1568

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Moira Kapral drafted the manuscript. Jiming Fang conducted the statistical analyses. Peter Austin provided additional statistical expertise related to the study design, analyses, and interpretation. Frank Silver, Moira Kapral, Ruth Hall, and Melissa Stamplecoski supervised data acquisition. All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, interpretation of the data, and revisions of the work for important intellectual content. All authors have given final approval of the version of the manuscript submitted for publication, and agree to be accountable for the work. Moira Kapral had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

STUDY FUNDING

This study was funded by the Ontario Stroke Network, which is funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The Ontario Stroke Registry is funded by the Canadian Stroke Network and the MOHLTC. The Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) is supported by an operating grant from the MOHLTC. The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred.

DISCLOSURE

M. Kapral is supported by Career Investigator awards from the Heart and Stroke Foundation, Ontario Provincial Office. R. Hall and J. Fang report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. P. Austin was previously supported by a Career Investigator award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation. F. Silver has served as a speaker for Boehringer Ingelheim Canada and Servier Canada and as a Canadian study coordinator for Boehringer Ingelheim Canada. D. Gladstone, L. Casaubon, and M. Stamplecoski report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. J. Tu is supported by Career Investigator awards from the Heart and Stroke Foundation, Ontario Provincial Office. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Giles MF, Rothwell PM. Risk of stroke early after transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:1063–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, et al. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischemic attack. Lancet 2007;369:283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Flossman E, et al. A simple score (ABCD) to identify individuals at high early risk of stroke after transient ischemic attack. Lancet 2005;366:29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coutts SB, Wein TH, Lindsay MP, et al. Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations: Secondary Prevention of Stroke guidelines, update 2014. Int J Stroke 2015;10:282–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2014;45:2160–2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gladstone DJ, Kapral MK, Fang J, Laupacis A, Tu JV. Management and outcomes of transient ischemic attacks in Ontario. Can Med Assoc J 2004;170:1099–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horer S, Haberl RL, Schulte-Altedorneburg G. Management of patients with transient ischemic attack is safe in an outpatient clinic based on rapid diagnosis and risk stratification. Cerebrovasc Dis 2011;32:504–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kehdi EE, Cordato DJ, Thomas PR, et al. Outcomes of patients with transient ischaemic attack after hospital admission or discharge from the emergency department. Med J Aust 2008;189:9–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lavallee PC, Meseguer E, Abboud H, et al. A transient ischaemic attack clinic with round-the-clock access (SOS-TIA): feasibility and effects. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:953–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olivot JM, Wolford C, Castle J, et al. Two aces: transient ischemic attack work-up as outpatient assessment of clinical evaluation and safety. Stroke 2011;42:1839–1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ross MA, Compton S, Medado P, Fitzgeral M, Kilanowski P, O'Neil BJ. An emergency department diagnostic protocol for patients with transient ischemic attack: a randomized controlled trial. Emerg Med 2007;50:109–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rothwell DM, Giles MF, Chandratheva A, et al. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS Study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet 2007;370:1432–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torres Macho J, Pena Lillo G, Perez Martinez D, et al. Outcomes of atherothrombotic transient ischemic attack and minor stroke in an emergency department: results of an outpatient management program. Ann Emerg Med 2011;57:510–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wasserman J, Perry D, Dowlatshahi D, et al. Stratified, urgent care for transient ischemic attack results in low stroke rates. Stroke 2010;41:2601–2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Webster F, Saposnik G, Kapral MK, Fang J, O'Callaghan C, Hachinski V. Organized outpatient care: stroke prevention clinic referrals are associated with reduced mortality after transient ischemic attack and ischemic stroke. Stroke 2011;42:3176–3182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Weitzel-Mudersbach PV, Johnsen SP, Andersen G. Low risk of vascular events following urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack: the Aarhus TIA Study. Eur J Neurol 2011;18:1285–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu CM, Mann BJ, Hill MD, Ghali WA, Donalson C, Buchan AM. Rapid evaluation after high-risk TIA is associated with lower stroke risk. Can J Neurol Sci 2009;36:450–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kapral MK, Fang J, Silver FL, et al. Effect of a provincial system of stroke care delivery on stroke care and outcomes. Can Med Assoc J 2013;185:E483–E491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kapral MK, Silver FL, Richards J, et al. Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network: Progress Report 2001–2005. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asplin BR. Measuring crowding: time for a paradigm shift. Acad Emerg Med 2006;13:459–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juurlink DN, Preyra C, Croxford R, et al. Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database: A Validation Study. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall RE, Khan F, O'Callaghan C, et al. Ontario Stroke Evaluation Report 2013: Spotlight on Secondary Stroke Prevention and Care. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Austin PC. The performance of different propensity score methods for estimating marginal odds ratios. Stat Med 2007;26:3078–3094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joshi JK, Ouyang B, Prabhakharan S. Should TIA patients be hospitalized or referred to a same-day clinic? A decision analysis. Neurology 2011;77:2078–2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly AG, Rothwell PM. Evaluating patients with TIA: to hospitalize or not to hospitalize? Neurology 2011;77:2078–2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez-Martinez MM, Martinez-Sanchez P, Fuentes B, et al. Transient ischemic attacks clinics provide equivalent and more efficient care than early in-hospital assessment. Eur J Neurol 2013;20:338–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paul NLM, Koton S, Geraghty OC, Luengo-Fernandez R, Rothwell PM. Feasibility, safety and cost of outpatient management of acute minor ischaemic stroke: a population-based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012;84:356–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casaubon LK, Kelloway L, Jaspers S. Ontario Stroke Network (OSN) ambulatory care triage algorithm for patients with suspected or confirmed transient ischemic attack or stroke. Ontario Stroke Network 2014. Available at: http://ontariostrokenetwork.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/OSN-Triage-algorithm-ver5-2014Dec1-FINAL.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2015.

- 30.Health Quality Ontario and Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Quality-Based Procedures: Clinical Handbook for Stroke (Acute and Post-Acute). Available at: http://www.hqontario.ca/Portals/0/Documents/eds/clinical-handbooks/community-stroke-20151802-en.pdf.2015. Accessed July 21, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall RE, Khan F, O'Callaghan C, et al. Ontario Stroke Evaluation Report 2014: On Target for Stroke Prevention and Care. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2014. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.