Abstract

The plant specific transcription factor LEAFY (LFY) plays a pivotal role in the developmental switch to floral meristem identity in Arabidopsis. Our recent study revealed that LFY additionally acts downstream of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR5/MONOPTEROS to promote flower primordium initiation. LFY also promotes initiation of the floral organ and floral organ identity. To further investigate the interplay between LFY and auxin during flower development, we examined the phenotypic consequence of disrupting polar auxin transport in lfy mutants by genetic means. Plants with compromised LFY activity exhibit increased sensitivity to disruption of polar auxin transport. Compromised polar auxin transport activity in the lfy mutant background resulted in formation of fewer floral organs, abnormal gynoecium development, and fused sepals. In agreement with these observations, expression of the auxin response reporter DR5rev::GFP as well as of the direct LFY target CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON2 were altered in lfy mutant flowers. We also uncovered reduced expression of ETTIN, a regulator of gynoecium development and a direct LFY target. Our results suggest that LFY and polar auxin transport coordinately modulate flower development by regulating genes required for elaboration of the floral organs.

Keywords: Arabidopsis thaliana, auxin transport, CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON2, ETTIN, flower development, LEAFY, PIN-FORMED1, PINOID

1. Introduction

The phytohormone auxin is a central regulator of lateral organ initiation [1,2,3,4]. Auxin accumulates in a graded and dynamic manner with the sites of auxin maxima correlating with the sites of primordium initiation [3,5]. The formation of auxin gradients is established by local auxin biosynthesis and polar auxin transport [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Direct transport is controlled by the PINFORMED (PIN) proteins, which encode auxin efflux carriers and exhibit polarized plasma membrane localization [1,2,3,4,5]. The Ser/Thr protein kinase PINOID (PID) catalyzes PIN phosphorylation and contributes to the regulation of apical-basal PIN polarity [9,10]. NAKED PINS IN YUC MUTANT (NPY) family genes, which encode NONPHOTOTROPIC HYPOCOTYL 3-like proteins, regulate PIN endocytosis and control auxin accumulation in incipient organ primordia [11,12,13]. On the other hand, YUCCA (YUC) flavin monooxygenase catalyzes a rate-limiting step in a tryptophan-dependent auxin biosynthesis pathway [14,15,16]. Mutations in PIN1, PINOID, NPY, and YUC result in inflorescences that form only a few flowers and grow as a pin-like structure [1,12,16,17].

Subsequent to determination of the primordium initiation site by an auxin maximum, the incipient flower primordium undergoes extensive growth. The AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR5/MONOPTEROS (ARF5/MP) has a central role translating local auxin concentration into specific gene expression outputs and flower initiation [18,19]. In the absence of auxin, MP activity is inhibited by the physical interaction between MP and Aux/IAA proteins such as BODENLOS/IAA12 [20,21], this represses transcription of downstream target genes involved in flower formation. Auxin sensing promotes the degradation of BDL/IAA12, resulting in MP-dependent transcriptional activation of target genes [20,21,22]. MP directly binds to the regulatory region of LEAFY (LFY), which specifies floral fate [23,24], and to two transcription factors, AINTEGUMENTA and AINTEGUMENTA-LIKE6/PLETHORA3 (AIL6/PLT3), key regulators of floral meristem outgrowth [25,26,27,28]. The lfy ant ail6 triple mutant is defective in flower primordium initiation, while reintroduction of LFY and ANT activity into mp mutants partially rescues the organogenesis defect [22]. These results suggest that upregulation of LFY, ANT, and AIL6/PLT3 by MP contributes to flower primordium initiation.

In addition to regulating floral primordium initiation, auxin also regulates floral organ development [29]. Plant harboring mutations in PIN1, PID, YUC, and NPY produce a few abnormal flowers [1,12,16,17]. These flowers typically have fewer sepals and stamens, more petals, fused floral organs, and valveless gynoecia. The observed alterations in gynoecium patterning are similar to those resulting from mutations in ETTIN (ETT), which encodes AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR3, or from treatment with an auxin transport inhibitor [30]. Floral organ fusion phenotypes are caused by loss-of-function mutations in the CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON (CUC) genes [31,32]. lfy single mutants do not display any defects in floral primordium initiation or in floral organ development, similarly to pin or pid mutants [1,17,23]. However, LFY interacts genetically with PID in lateral organ primordium initiation [33].

Here, we further probe the interactions between LFY and polar auxin transport. We have examined the consequences of loss-of-LFY function in plants compromised in polar auxin transport by genetic means. These experiments demonstrate that LFY promotes not only flower primordium initiation, but also subsequent floral organ initiation and development, in concert with polar auxin transport. LFY executes this role likely via regulating downstream direct targets, such as CUC2 and ETT, whose activity is also controlled by polar auxin transport. Our study uncovers a complex set of interactions between LFY and the auxin pathway in flower development.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Loss-of-LFY Function Enhances Floral Primordium Initiation Defects of pin1 and pid Mutants

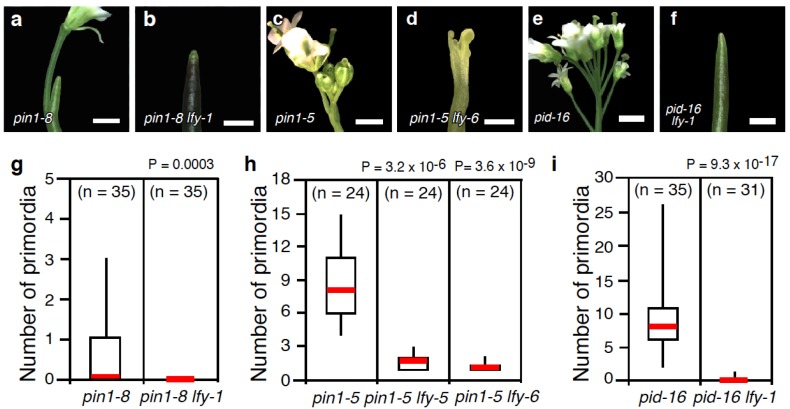

Because pin1 and pid single mutants make several flowers, they provide a sensitized background in which to study the interplay between LFY and auxin transport during flower primordium initiation. We first introduced the lfy-1 (Col) null mutant into pin1 mutants. The strong pin1-8 allele formed naked inflorescences with a few flowers, as reported previously (Figure 1a,g) [1,34]. In pin1-8 lfy-1 double mutants, no flowers were produced (Figure 1b,g; p < 10−3). By contrast, the weak pin1-5 allele formed approximately 8 flowers per inflorescence, as described previously (Figure 1c,h) [17]. While flowers were produced in double mutants between pin1-5 and the weak lfy-5 or lfy-6 (Ler) null mutants, they were dramatically reduced in number compared to the pin1-5 single mutant (Figure 1d,h). These genetic interactions suggest that LFY acts synergistically with polar auxin transport to promote flower primordium initiation.

Figure 1.

lfy enhances the floral primordium initiation defects of auxin transport mutants. (a–f) Close-up view of the inflorescences formed in a strong pin1 mutant allele, pin1-8 (a); and pin1-8 lfy-1 (b); a weak pin1 mutant allele, pin1-5 (c); and pin1-5 lfy-6 (d); pid-16 (e) and pid-16 lfy-6 (f); (g–i) Quantification of the flower initiation defects in pin1-8 and pin1-8 lfy-1 (g); pin1-5, pin1-5 lfy-5, and pin1-5 lfy-6 (h); and pid-16 and pid-16 lfy-6 (i). Note that lfy-1 and lfy-6 carry the exact same mutation (Q32stop) but are the Columbia (Col) and Landsberg erecta (Ler) cultivar, respectively. We employ both alleles as to eliminate mixed genetic backgrounds when generating double mutants. Scale bar, 200 µm (a,b,d,f), 5 mm (c,e).

We next investigated the effect of introducing lfy-1 into pid mutant background using the strong pid-16 allele (Figure 1e,i). pid-16 lfy-1 produced only a few flowers compared to the pid-16 single mutant (Figure 1i; (p < 10−16)). Taken together, the inability of lfy mutants to initiate flower primordia in genetic backgrounds defective in polar auxin transport confirms the proposed role for LFY in auxin-mediated flower primordium initiation [22]. Consistent with this finding, a recent genetic screen identified a pid mutation as a second site enhancer of weak lfy-5 mutants [33].

Previously, it has been reported that pin-like apices of pin1 single and pin1 lfy double mutants retain auxin responsiveness with respect to formation of lateral organs such as flowers and cauline leaves in the inflorescence [2,4]. By contrast, strong mp mutants are no longer responsive to auxin [2]. These findings are consistent with the observation that additional direct MP targets act in parallel with LFY in flower primordium initiation [22]. Our data are consistent with the strikingly enhanced defects in lateral organ initiation observed in mp pid or mp pin double mutants [35], which suggest that MP and MP targets like LFY act, in part, in parallel with these regulators of polar auxin transport.

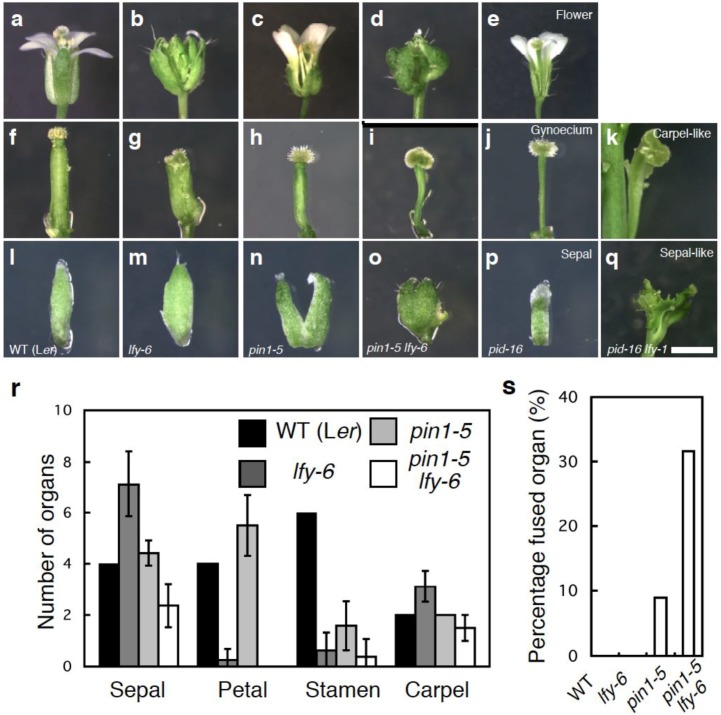

2.2. Mutations in LFY Enhance Floral Organ Initiation and Growth Defects of pin1 Mutants

Because only pin1-5 lfy-6 inflorescences make a reasonable number of flowers prior to a naked pin, we first examined the effect of loss of LFY function on floral organ development in the pin1-5 mutant. Floral organs in wild-type plants are arranged in a series of whorls: four sepals in the outer whorl, followed by four petals, six stamens, and two carpels (Figure 2a,r). As reported previously, lfy mutant flowers display floral homeotic defects. lfy null mutants rarely form petals and stamens and largely consist of sepal- and carpel-like organs [23] (Figure 2b,r). This is consistent with molecular and genetic data, which show that LFY plays a major role in the up-regulation of the class B and class C floral homeotic genes [36,37,38]. On the other hand, the weak pin1-5 flowers formed all four types of floral organs, like wild-type flowers (Figure 2c,r). However, pin1-5 flowers showed an increase in the number of petals, and a decrease in the number of stamens formed (Figure 2r) [17]. In addition, pin1-5 resulted in a reduction of the valve region and expansion of the stylar and stigmatic regions of the gynoecium (Figure 2f–h). Finally, pin1-5 sepals are often fused (Figure 2l–n). These phenotypes are common in flowers of auxin defective mutants [15,16,30].

Figure 2.

lfy enhances the flower developmental defects of auxin transport mutants. (a–e) Side view of the flowers formed in wild type (a), lfy-6 (b), pin1-5 (c), pin1-5 lfy-6 (d), pid-16 (e); (f–k) Side view of the gynoecium formed in wild type (f), lfy-6 (g), pin1-5 (h), pin1-5 lfy-6 (i), pid-16 (j), pid-16 lfy-1 (k); (l–q) Side view of the sepal formed in wild type (l), lfy-6 (m), pin1-5 (n), pin1-5 lfy-6 (o), pid-16 (p), pid-16 lfy-1 (q); (r) Floral organ number in wild-type, lfy-6, pin1-5, and lfy-6 pin1-5 flowers; (s) Incidence of sepal fusion in wild-type, lfy-6, pin1-5, and lfy-6 pin1-5 flowers. Scale bar, 2 mm.

pin1-5 lfy-6 exhibited a reduction in the number of all four floral organs formed, compared with the wild-type or parental lines and generally lacked petals and stamens (Figure 2d,r). The sepal fusion and abnormal gynoecium phenotype of pin1-5 was enhanced in the double pin1-5 lfy-6 mutants (Figure 2h,i,n,o). The length of the fused sepal margin increased when compared with pin1-5 single mutant flowers. The incidence of sepal fusion also increased in pin1-5 lfy-6 flowers (32%) compared to pin1-5 flowers (8.9%) (Figure 2s). In individual plants, sepal fusions became more severe and frequent acropetally (Figure 2n,o). Additionally, the size of the stigmatic and ovary regions in the gynoecium increased and decreased, respectively when compared with pin1-5 single mutant flowers (Figure 2h,i). Although pin1-5 formed a few seeds, pin1-5 lfy-6 flowers were infertile, like lfy-6 mutants (data not shown).

To further confirm the role of LFY in auxin transport-mediated flower development, we examined genetic interaction between LFY and PID. pid-16 single mutants produced several flowers with fewer floral organs (Figure 2e). The flowers produced by pid-16 lfy-1 plants exhibited more severe phenotypic defects than those observed in pid-16 alone (Figure 2e,j,k,p,q). pid-16 lfy-1 flowers never formed petals and stamens (Figure 2k). Flowers of pid-16 lfy-1 double mutants were comprised of either several fused carpel-like or sepal-like organs (Figure 2k,q). In addition these abnormal flowers often displayed fusion with the pedicel (Figure 2k,q). Thus, LFY may act together with polar auxin transport in sepal and gynoecium development.

2.3. The Relationship between LFY and Auxin-Mediated Sepal Initiation

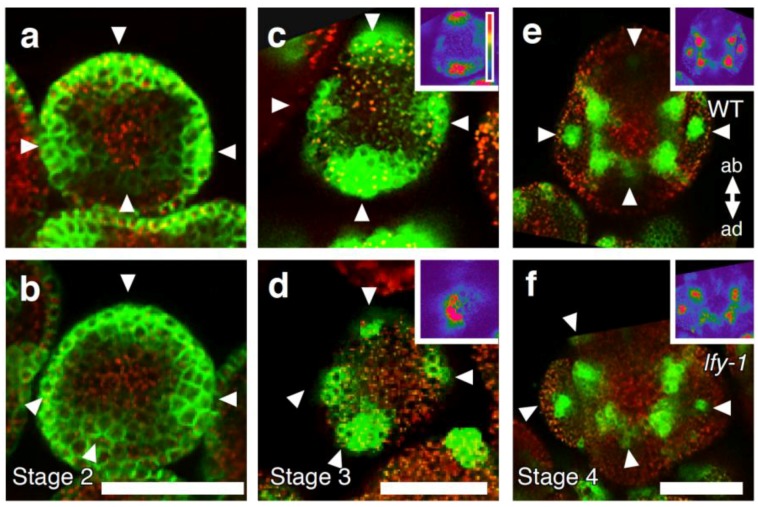

The sepal phenotype observed in pin1 lfy flowers may be due to an alteration in the positioning of sepal primordia in the floral meristem and/or the inability to establish boundaries between adjacent organs. To better understand how loss of LFY function affects sepal formation, we examined sepal primordium positioning by monitoring expression of the auxin efflux carrier protein, PIN1, and the auxin response promoter DR5. In stage 2 wild-type flowers, PIN1-GFP was expressed in the incipient sepal primordia at symmetrical positions within the flower meristem (Figure 3a). The PIN1-GFP positive sites of sepal primordium initiation in stage 2 flowers of lfy mutants were not properly spaced, as in the wild type. Frequently two incipient sepal primordia formed in close proximity (Figure 3a,b). In wild-type plants, DR5rev::GFP was expressed in the sepal primordia, as reported previously [3,39]. On the basis of DR5rev::GFP, wild-type sepals developed four discrete sepal primordia at symmetrical positions (Figure 3c). Like lfy floral primordia [22,33], lfy sepal primordia showed slightly reduced DR5 expression, especially at the abaxial and the lateral side of the sepals (Figure 3c,d insets). Although we saw an increase in the number of sepals in lfy mutants at later stages, stage 3 lfy-1 mutant flowers only had four sepal primordia based on DR5 expression (Figure 3c,d). These data suggest that additional sepal primordia form after stage 3 in lfy flowers. As seen for the PIN1-GFP expression, the sites of sepal initiation marked by DR5 in stage 3 flowers of lfy mutants were not properly spaced in the floral primordium; frequently two sepal primordia formed in close proximity (Figure 3b,d). At stage 4 of flower development, DR5 expression in lfy sepals was often not perfectly cruciform, but somewhat twisted (Figure 3e,f). Hence, LFY is required for proper positioning of sepal primordia.

Figure 3.

Floral organ primordium initiation in lfy loss-of-function mutant flowers. (a,b) pPIN1::PIN1-GFP expression in wild-type (a) and lfy (b) flowers at stage 2. (c–f) DR5rev::GFP expression in wild-type (c,e) and lfy (d,f) flowers at stage 3 (c,d) and stage 4 (e,f). Strongly increased GFP signal was observed in sepal primordia (arrowheads), as reported previously [3,39]. Insets show color-coded GFP intensity, with background levels being purple and blue, green, yellow, and red to signifying increasing DR5rev::GFP signal. ab, abaxial; ad, adaxial. Scale bar, 25 µm.

2.4. A Link between LFY and Polar Auxin Transport in Sepal Boundary Formation

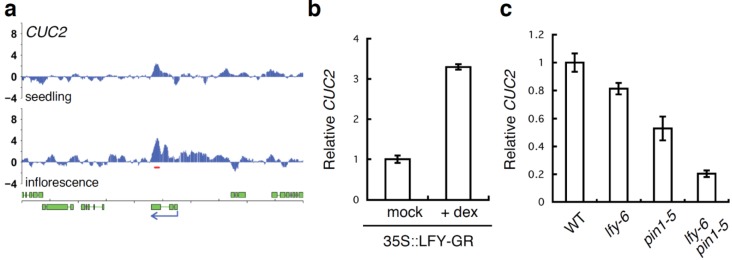

A further connection between LFY and sepal development was suggested by genome-wide identification of LFY binding sites [37,40]. The most highly enriched Gene Ontology terms among direct LFY targets in the inflorescence were “organ development” and “flower development” [37,40]. Amongst the candidate direct LFY targets identified by these studies, one gene with a known role in organ boundary formation stood out, CUC2. Although LFY is already expressed prior to flower formation [41], LFY only bound to the 5'-regulatory region of the CUC2 gene in inflorescences (Figure 4a), suggesting that LFY regulates CUC2 expression specifically at this stage. We further found that CUC2 mRNA levels rapidly increased upon 35S::LFY-GR activation in inflorescences (Figure 4b). In addition, CUC2 showed a subtle, but reproducible reduction of expression in lfy-6 null mutants relative to the wild type (Figure 4c). CUC2 mRNA levels were also reduced in pin1-5 mutants. Furthermore, a more dramatic reduction in CUC2 expression was observed in pin1-5 lfy-6 compared to the wild type or the parental lines, suggesting that both LFY and auxin transport are important for proper CUC2 induction in the flower.

Figure 4.

LFY regulates CUC2 gene expression. (a) LFY binds to the regulatory regions of CUC2 gene based on a published ChIP-chip data set [37]. Screenshots of the binding peaks (blue vertical lines). Significant LFY-binding peaks are indicated by a red horizontal line below the peaks. Green boxes below the graphs denote exons, blue arrows indicate the direction of transcription; (b) Expression of the CUC2 gene based on qRT-PCR three hours after mock or dexamethasone (dex) treatment of lfy-6 35S::LFY-GR inflorescences; (c) Expression of the CUC2 gene based on qRT-PCR in lfy-6 null mutant, the weak pin1-5 mutant, and pin1-5 lfy-6 double mutant inflorescence apices compared to wild-type inflorescence apices. RNA from floral bud clusters (containing stages 1–6 flowers) was used in this study.

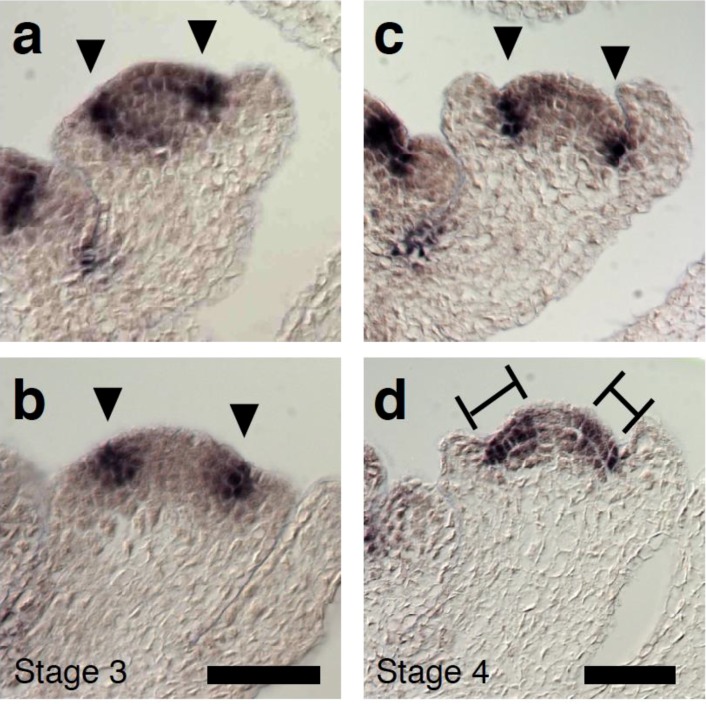

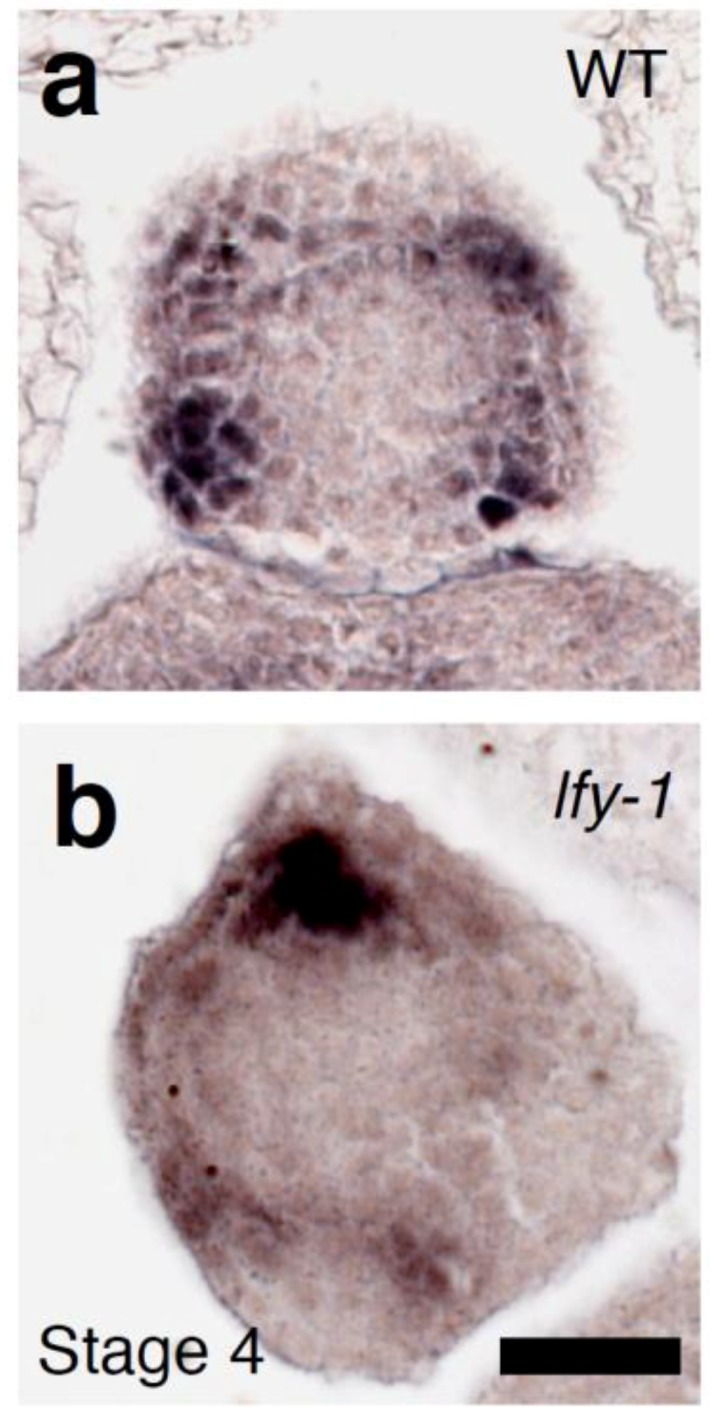

To further test the relationship between LFY and CUC2, we performed in situ hybridization. In wild-type plants, CUC2 was expressed in the sepal boundary of stage 3 flowers, as reported for CUC1 or CUC3 (Figure 5a) [42,43]. CUC2 expression pattern and levels were essentially the same in stage 3 wild type and lfy-1 flowers (Figure 5b). In stage 4 wild-type flowers, strong CUC2 expression was observed in the boundary region between the sepal primordia and the floral meristem dome, where growth is retarded (Figure 5c,e). However, CUC2 expression in the boundary between the sepal primordia and the floral meristem dome was frequently weaker in stage 4 lfy-1 flowers and CUC2 expression was overall more diffuse (Figure 5d). Occasionally, CUC2 expression was entirely missing from a boundary region (Appendix Figure A1).

Figure 5.

Altered CUC2 gene expression in LFY loss-of-function flowers. (a–d) CUC2 expression in wild-type (a,c) and lfy (b,d) flowers at stage 3 (a,b) and stage 4 (c,d). Arrowheads denote the boundary between the floral meristem and the sepals. Bars indicate diffused CUC2 expression. Scale bar, 25 µm.

It has been reported that CUC1 and CUC2 genes act redundantly in regulating formation of the sepal boundary [31], and that CUC2 expression is affected by auxin transport [44]. Since we could observe both a sepal fusion phenotype and a dramatic reduction of CUC2 mRNA levels in pin1 lfy double mutants, the combined data are consistent with the idea that LFY and polar auxin transport may modulate CUC2 expression in the sepal boundary.

2.5. A Link between LFY and Auxin Transport in Gynoecium Development

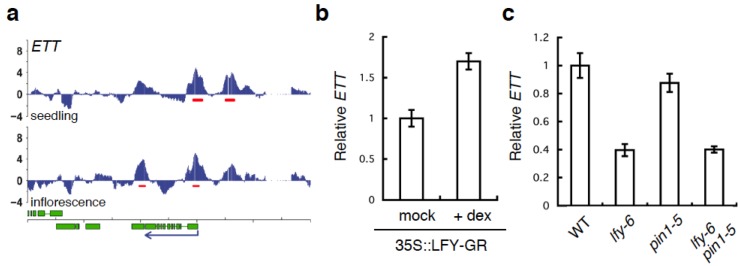

Among the LFY-bound genes identified by ChIP-Seq or ChIP-chip are many genes in the auxin pathway [22,37,40], several of which have been implicated in gynoecium development [12,15,30]. Thus, several potential direct LFY target genes may underlie the gynoecium formation defects observed in pin lfy mutants. Because the single ett null mutant displays gynoecium defects very similar to those we observed here [30], we focused on the relationship between LFY and ETT. Two strong LFY binding peaks were present at the ETT locus in inflorescences, one in the promoter and one in the ninth intron (Figure 6a). When we tested ETT expression by qRT-PCR, we found that ETT mRNA was reduced in lfy mutants and rapidly increased upon 35S::LFY-GR activation in inflorescences (Figure 6b,c). These results suggest that LFY may activate ETT to regulate gynoecium development. However, we did not see a strong reduction of ETT expression in pin1-5 mutants compared to wild type (Figure 6c). Moreover, no further change in ETT expression was observed in pin1-5 lfy-6 mutant relative to lfy-6 mutant inflorescences (Figure 6c). Thus, additional regulators of gynoecium development besides ETT may contribute to the developmental defects observed in pin1 lfy double mutants.

Figure 6.

LFY regulates the ETT gene. (a) LFY binds to the regulatory regions of the ETT gene based on a published ChIP-chip data set [37]. Screenshots of the LFY binding peaks (blue vertical lines). Significant LFY-binding peaks are indicated by a red horizontal line below the peaks. Green boxes below the graphs denote exons, blue arrows indicate the direction of transcription; (b) Expression of the ETT gene based on qRT-PCR three hours after mock or dexamethasone (dex) treatment of lfy-6 35S::LFY-GR inflorescences (c) Expression of the ETT gene based on qRT-PCR in lfy-6 null mutant, weak pin1-5 mutant, and pin1-5 lfy-6 double mutant inflorescence apices compared to wild-type inflorescence apices. RNA from floral bud clusters (containing stages 1-6 flowers) was used in this study.

Alternatively, reduced ETT accumulation in lfy mutants combined with reduced ETT activity in pin1-5 may cause the observed gynoecium defect. Although the ETT protein lacks the conserved domains III and IV for interaction with AUX/IAA proteins [45], it has been reported that the transcriptional repressor ETT suppresses a synthetic AuxRE-based reporter in protoplasts in an auxin-dependent manner [46], and pin1 mutants have reduced auxin accumulation [1]. In agreement with this study, treatment with the auxin transport inhibitor NPA enhanced the gynoecium defects of weak ett mutants to phenocopy ett null mutants, while ett null mutant gynoecium defects were not enhanced by this treatment [30]. Thus, we favor a model in which the reduction of ETT mRNA level (due to the lfy mutation) and attenuated ETT protein activity (due to the pin1 mutation/low auxin level) cause gynoecium developmental defects in pin1 lfy double mutants. Further studies are required to resolve how auxin modulates ETT activity in the gynoecium.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Plants were grown at 23 °C in a 16 h light/8 h dark cycle. Arabidopsis thaliana accessions Columbia (Col) or Landsberg erecta (Ler) were used in this study. Mutants employed were: lfy-1 [23], lfy-6 [23], pin1-5 [17], pin1-8 (SALK_97114) [34], pid-16 (SALK_082564), 35S::LFY-GR [47], and DR5rev::GFP [3]. For dexamethasone treatments, plants were grown in soil. Dexamethasone treatments were performed by spraying 30-day-old plants once with 5 µM dexamethasone.

3.2. Statistical Tests

The Student t-test (two-tailed) was used for all experiments that displayed a normal distribution based on the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test [48].

3.3. Genetics and PCR Genotyping

lfy/+ plants were crossed to pin1-5, pin1-8/+, or pid-16/+ plants. Double mutants were identified in the F2 or later generations as plants with new phenotypes and confirmed by PCR genotyping. lfy mutations were PCR genotyped as described previously. Genotyping primers are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sets used in this study.

| Primer name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Genotyping | |

| lfy-1/-6-FW | AAGCAGCCGTCTGCGGTGTCAGCAGCTGTT |

| lfy-1/-6-RV | CTGTCAATTTCCCAGCAAGACAC |

| pid-16-LP | TCCGTCATAGACAACCTCACC |

| pid-16-RP | GAGTAAGCGTACGAATGAGCG |

| pin1-8-LP | AACTGGCTTCACAGCAGAAAG |

| pin1-8-RP | TCAACAAAAAGGGCATTGTTC |

| LBb1.3 | ATTTTGCCGATTTCGGAAC |

| Primer name | Sequence |

| qRT-PCR | |

| CUC2-FW | GGAAGAGCTCCGAAAGGAGA |

| CUC2-RV | TCCGGTGCTAGCTAAAGTGG |

| ETT-FW | CAGGGACATTTGGAACAAGC |

| ETT-RV | CAGGAAGAAGAGAGACTTGAGCA |

| EIF4-FW | AAACTCAATGAAGTACTTGAGGGACA |

| EIF4-RV | TCTCAAAACCATAAGCATAAATACCC |

| In situ hybridization | |

| CUC2-FW | CGGAATTCATGGACATTCCGTATTACCA |

| CUC2-RV | CCACTAGTTCAGTAGTTCCAAATACAGT |

3.4. Confocal Microscopy

Imaging of GFP signal was performed as described by [22]. For imaging of GFP signal, inflorescence apices were dissected to remove older flowers and imaged for green and red fluorescence using a Leica confocal microscope (Leica, LCS SL) equipped with an argon-krypton ion laser with the appropriate filter sets for visualizing GFP and propidium iodide. For comparisons of GFP fluorescence, the same offset and gain settings were used in the analysis of plants that were transformed with the same transgene. At least ten inflorescences were prepared from different plants, and representative images are shown.

3.5. Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA from floral bud clusters (containing stages 1–6 flowers) was used in this study. Total RNA was extracted from inflorescences using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) and was treated with DNase (Qiagen) prior to RT. cDNA was synthesized from 0.5 ng of total RNA with the Super Script III (Invitrogen). qRT-PCR was performed as previously described by Yamaguchi et al. [22]. Real-time PCR was performed with the 7100 Real-Time PCR system and Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), as described by the manufacturer. The means and standard errors were determined using two to three biological replicates with three technical replicates each. Plant materials were grown and harvested at different times. One representative experiment is shown. Gene-specific signals were normalized over that of the EUKARYOTIC TRANSLATION INITIATION FACTOR 4A-1 (EIF4; At1g54270). Primers are shown in Table 1.

3.6. Screenshot

Significant LFY binding to regulatory regions of CUC2 and ETT in seedlings and inflorescences were generated by Winter et al. [37].

3.7. In situ Hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed as described previously [49,50]. The CUC2 probe consisted of base pairs 29 to 1137 (TSS = 1). Cloning primers are shown in Table 1. Probes were cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega). Antisense CUC2 probe was digested with EcoRI and transcribed with the T7 polymerase. The Riboprobe Combination System (Promega) and DIG RNA labeling mix (Roche) were used for probe synthesis.

4. Conclusions

The plant specific transcription factor LFY is necessary and sufficient for the developmental transition to flower formation [23,24] Previous genomic, genetic, and molecular analyses have suggested a role for LFY downstream of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR5/MONOPTEROS in flower primordium initiation [22,37,40]. In addition, LFY feedback regulates the auxin pathway [22,33]. Finally, like MP, LFY also acts in a pathway parallel to the polar auxin transport regulators PID and PIN1 in lateral organ initiation (this study) [33,35]. We have uncovered enhanced sensitivity of lfy mutants to alterations in polar auxin transport in other aspects of flower morphogenesis such as floral organ initiation and sepal and gynoecium development. It is difficult to know whether the interactions between auxin transport and LFY are direct, via changes in auxin concentrations, or indirect via combinatorial effects on gene expression. Disruption of polar auxin transport has a dramatic effect on expression of a spectrum of genes [51]. We provide evidence that transcriptional regulation of the organ boundary regulator CUC2 and the gynoecium development regulator ETT by LFY (this study) and auxin [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17] may contribute to defects in sepal and gynoecium development observed in double mutants between polar auxin transport regulators and lfy. Our study combined with prior investigations reveals a complex set of interactions between LFY and polar auxin transport in developing flowers.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jiri Friml for pPIN1::PIN1-GFP and DR5rev::GFP seeds, and the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center for insertion seeds. This work was supported by NSF grant IOS-1257111 to D.W. and JSPS postdoctoral fellowships for research abroad to N.Y.

Appendix

Figure A1.

Altered CUC2 gene expression in LFY loss-of-function flowers. (a,b) CUC2 expression in wild-type (a) and lfy (b) flowers at stage 4. Arrowheads denote the boundary between the floral meristem and the sepals. Scale bar, 25 µm.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Okada K., Ueda J., Komaki M.K., Bell C.J., Shimura Y. Requirement of the Auxin Polar Transport System in Early Stages of Arabidopsis Floral Bud Formation. Plant Cell. 1991;3:677–684. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.7.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reinhardt D., Mandel T., Kuhlemeier C. Auxin regulates the initiation and radial position of plant lateral organs. Plant Cell. 2000;12:507–518. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.4.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benkova E., Michniewicz M., Sauer M., Teichmann T., Seifertova D., Jurgens G., Friml J. Local, efflux-dependent auxin gradients as a common module for plant organ formation. Cell. 2003;115:591–602. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00924-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reinhardt D., Pesce E.R., Stieger P., Mandel T., Baltensperger K., Bennett M., Traas J., Friml J., Kuhlemeier C. Regulation of phyllotaxis by polar auxin transport. Nature. 2003;426:255–260. doi: 10.1038/nature02081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heisler M.G., Ohno C., Das P., Sieber P., Reddy G.V., Long J.A, Meyerowitz E.M. Patterns of auxin transport and gene expression during primordium development revealed by live imaging of the Arabidopsis inflorescence meristem. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:1899–1911. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stepanova A.N., Rovertson-Hoyt J., Yun J., Benavente L.M., Xie D.Y., Dolezal K., Schlereth A., Jurgens G., Alonso J.M. TAA-mediated auxin biosynthesis is essential for hormone crosstalk and plant development. Cell. 2008;133:177–191. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao Y. Auxin biosynthesis and its role in plant development. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010;61:49–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robert H.S., Grones P., Stepanova A.N., Robles L.M., Lokerse A.S., Alonso J.M., Weijers D., Friml J. Local auxin sources orient the apical-basal axis in Arabidopsis embryos. Curr. Biol. 2013;23:2506–2512. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friml J., Yang X., Michniewicz M., Weijers D., Quint A., Tietz O., Benjamins R., Ouwerkerk P.B., Ljung K., Sandberg G., et al. A PINOID-dependent binary switch in apical-basal PIN polar targeting directs auxin efflux. Science. 2004;306:862–865. doi: 10.1126/science.1100618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michniewicz M., Zago M.K., Abas L., Weijers D., Schweighofer A., Meskiene I., Marcus G.H., Ohno C., Zhang J., Huang F., et al. Antagonistic regulation of PIN phosphorylation by PP2A and PINOID directs auxin flux. Cell. 2007;130:1044–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng Y., Qin G., Dai X., Zhao Y. NPY1, a BTB-NPH3-like protein, plays a critical role in auxin-regulated organogenesis in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:18825–18829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708506104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng Y., Qin G., Dai X., Zhao Y. NPY genes and AGC kinases define two key steps in auxin-mediated organogenesis in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:21017–21022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809761106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furutani M., Nakano Y., Tasaka M. MAB4-induced auxin sink generates local auxin gradients in Arabidopsis organ formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;11:1198–1203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316109111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao Y., Christensen S.K., Fankhauser C., Cashman J.R., Cohen J.D., Weigel D., Chory J. A role for flavin monooxygenase-like enzymes in auxin biosynthesis. Science. 2001;291:306–309. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5502.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng Y., Dai X., Zhao Y. Auxin biosynthesis by the YUCCA flavin monooxygenase controls the formation of floral organs and vascular tissues in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1790–1799. doi: 10.1101/gad.1415106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng Y., Dai X., Zhao Y. Auxin synthesized by the YUCCA flavin monooxygenases is essential for embryogenesis and leaf formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2430–2439. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.053009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett S.R.M., Alvarez J., Bossinger G., Smyth D.R. Morphogenesis in pinoid mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1995;8:505–520. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Przemeck G.K., Mattsson J., Hardtke C.S., Sung Z.R., Berleth T. Studies on the role of the Arabidopsis gene MONOPTEROS in vascular development and plant cell axialization. Planta. 1996;200:229–237. doi: 10.1007/BF00208313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardtke C.S., Berleth T. The Arabidopsis gene MONOPTEROS encodes a transcription factor mediating embryo axis formation and vascular development. EMBO J. 1998;17:1405–1411. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamann T., Benkova E., Baurle I., Kientz M., Jurgens G. The Arabidopsis BODENLOS gene encodes an auxin response protein inhibiting MONOPTEROS-mediated embryo patterning. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1610–1615. doi: 10.1101/gad.229402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weijers D., Schlereth A., Ehrismann J.S., Schwank G., Kientz M., Jurgens G. Auxin triggers transient local signaling for cell specification in Arabidopsis embryogenesis. Dev. Cell. 2006;10:265–270. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamaguchi N., Wu M-F., Winter C., Berns M., Nole-Wilson S., Yamaguchi A., Coupland G., Krizek B., Wagner D. A molecular framework for auxin-mediated initiation of floral promordia. Dev. Cell. 2013;24:271–282. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weigel D., Alvarez J., Smyth D.R., Yanofsky M.F., Meyerowitz E.M. LEAFY controls floral meristem identity in Arabidopsis. Cell. 1992;69:843–859. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90295-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weigel D., Nilsson O. A developmental switch sufficient for flower initiation in diverse plants. Nature. 1995;377:495–500. doi: 10.1038/377495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elliott R.C., Betzner A.S., Huttner E., Oakes M.P., Tucker W.Q.J., Gerentes D., Perez P., Smyth D.R. AINTEGUMENTA, an APETALA2-like gene of Arabidopsis with pleiotropic roles in ovule development and floral organ growth. Plant Cell. 1996;8:155–168. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.2.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krizek B.A. Ectopic expression of AINTEGUMENTA in Arabidopsis plants results in increased growth of floral organs. Dev. Genet. 1999;25:224–236. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1999)25:3<224::AID-DVG5>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mizukami Y., Fischer R.L. Plant organ size control: AINTEGUMENTA regulates growth and cell numbers during organogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:942–947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krizek B.A. AINTEGUMENTA and AINTEGUMENTA-LIKE6 act redundantly to regulate Arabidopsis floral growth and patterning. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:1916–1929. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.141119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krizek B.A. Auxin regulation of Arabidopsis flower development involves members of the AINTEGUMENTA-LIKE/PHETHORA (AIL/PLT) family. J. Exp. Bot. 2011;62:3311–3319. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nemhauser J.L., Feldman L.J., Zambryski P.C. Auxin and ETTIN in Arabidopsis gynoecium morphogenesis. Development. 2000;127:3877–3888. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.18.3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aida M., Ishida T., Fukaki H., Fujisawa H., Tasaka M. Genes involved in organ separation in Arabidopsis: An analysis of the cup-shaped cotyledon mutant. Plant Cell. 1997;9:841–857. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.6.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sieber P., Wellmer F., Gheyselinck J., Riechmann J.L., Meyerowitz E.M. Redundancy and specillization among plant microRNAs: Role of the MIR164 familiy in developmental robstness. Development. 2007;134:1051–1060. doi: 10.1242/dev.02817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li W., Zhou Y., Liu X., Yu P., Cohen J.D., Meyeriwitz E.M. LEAFY controls auxin response pathways in floral primordium formation. Sci. Signal. 2013;6:ra23. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawamura E., Horiguchi H., Tsukaya H. Mechanisms of leaf tooth formation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2010;62:429–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schuetz M., Berleth T., Mattsson J. Multiple MONOPTEROS-dependent pathways are involved in leaf initiation. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:870–880. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.119396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weigel D., Meyerowitz E.M. Activation of floral homeotic genes in Arabidopsis. Science. 1993;261:1723–1726. doi: 10.1126/science.261.5129.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winter C.M., Austin R.S., Blanvillain-Baufume S., Reback M.A., Monniaux M., Wu M.F., Sang Y., Yamaguchi A., Yamaguchi N., Parker J.E., et al. LEAFY Target Genes Reveal Floral Regulatory Logic, cis motifs, and a link to biotic stimulus response. Dev. Cell. 2011;20:430–443. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu M.F., Sang Y., Bezhani S., Yamaguchi N., Han S.K., Li Z., Su Y., Slewinski T.L., Wagner D. SWI2/SNF2 chromatin remodeling ATPases overcome polycomb repression and control floral organ identity with the LEAFY and SEPALLATA3 transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:3576–3581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113409109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lampugnani E.R., Kilinc A., Smyth D.R. PETAL LOSS is a boundary gene that inhibits growth between developing sepals in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2012;71:724–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moyroud E., Minguet E.G., Ott F., Yant L., Pose D., Monniaux M., Blanchet S., Bastien O., Thevenon E., Weigel D., et al. Prediction of regulatory interactions from genome sequences using a biophysical model for the Arabidopsis LEAFY transcription factor. Plant Cell. 2011;23:1293–1306. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.083329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blazquez M.A., Soowal L.N., Lee I., Weigel D. LFY expression and flower initiation in Arabidopsis. Development. 1998;121:3835–3844. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.19.3835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takada S., Hibara K., Ishida T, Tasaka M. The CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON1 gene of Arabidopsis regulates shoot apical meristem formation. Development. 2001;128:1127–1135. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.7.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hibara K., Karim M.R., Takada S., Taoka K., Furutani M., Aida M., Tasaka M. Arabidopsis CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON3 regulates postembryonic shoot meristem and organ boundary formation. Plant Cell. 2006;18:2946–2957. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.045716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bilsborough G.D., Runions A., Barkoulas M., Jenkins H.W., Hasson A., Galinha C., Laufs P., Hay A., Prusinkiewicz P., Tsiantis M. Model for the regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana leaf margin development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:3424–3429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015162108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hagen G., Guilfoyle T. Auxin-responsive gene expression: Genes, promoters and regulatory factors. Plant Mol. Biol. 2002;49:373–385. doi: 10.1023/A:1015207114117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tiwari S.B., Hagen G., Guilfoyle T. The roles of auxin response factor domains in auxin responsive transcription. Plant Cell. 2003;15:533–543. doi: 10.1105/tpc.008417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wagner D., Sablowski R.W., Meyerowitz E.M. Transcriptional activation of APETALA1 by LEAFY. Science. 1999;285:582–584. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5427.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Massay F.J. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for goodness of fit. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1951;46:68–78. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1951.10500769. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Long J.A., Barton M.K. The development of apical embryonic pattern in Arabidopsis. Development. 1998;125:3027–3035. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.16.3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu M.F., Wagner D. RNA in situ hybridization in Arabidopsis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012;883:75–86. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-839-9_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nemhauser J.L., Hong F., Chory J. Different plant hormones regulate similar processes through largely nonoverlapping transcriptional responses. Cell. 2006;126:467–475. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]