Abstract

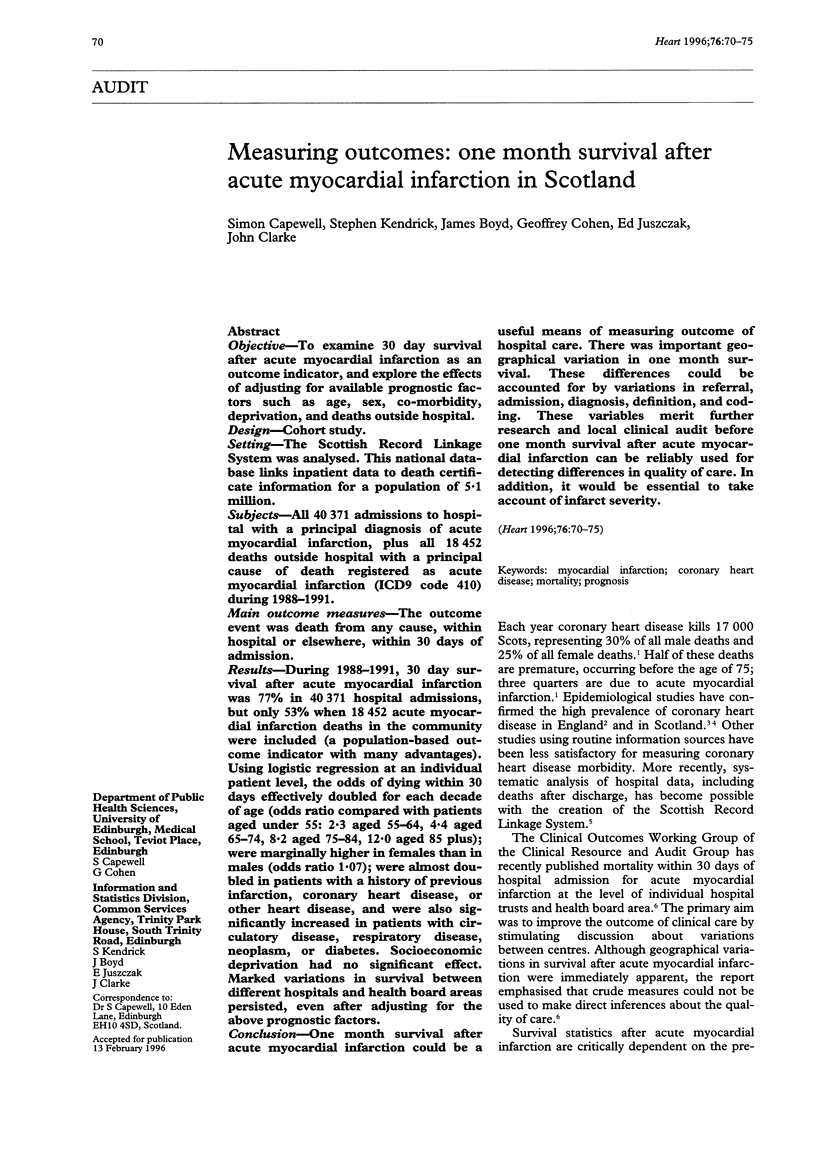

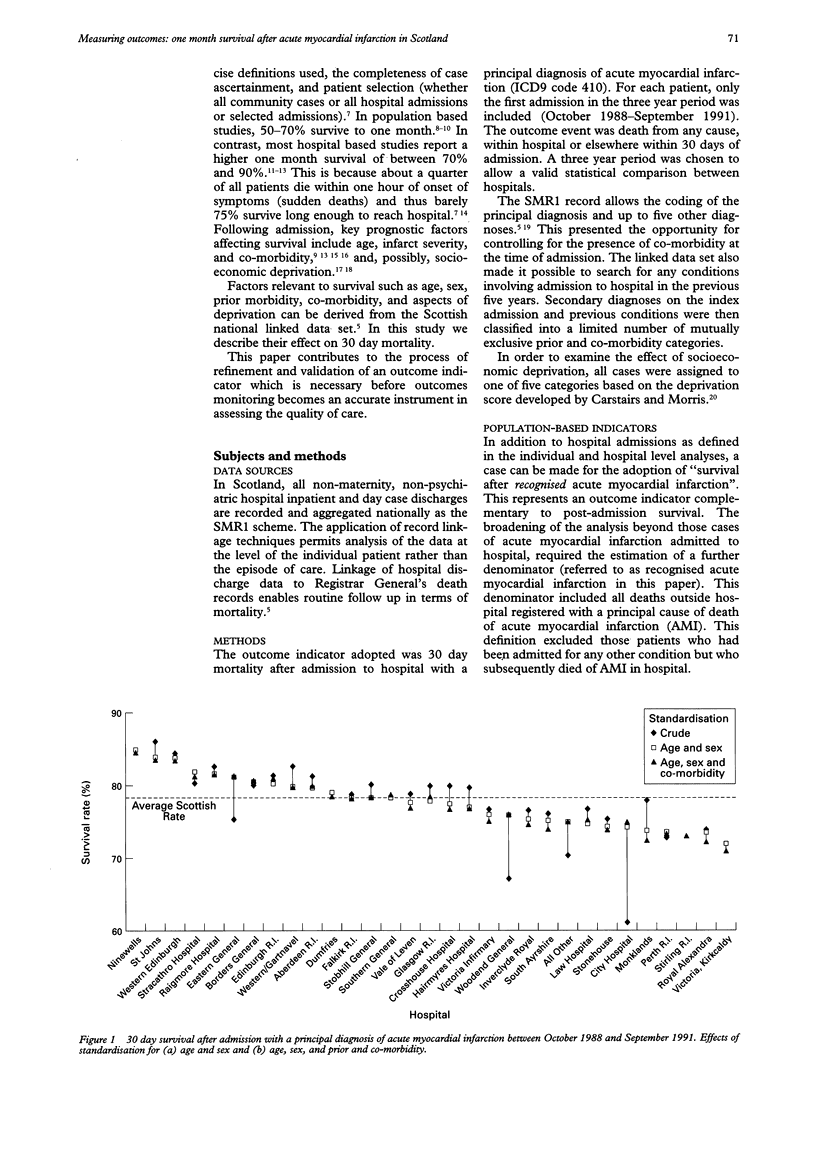

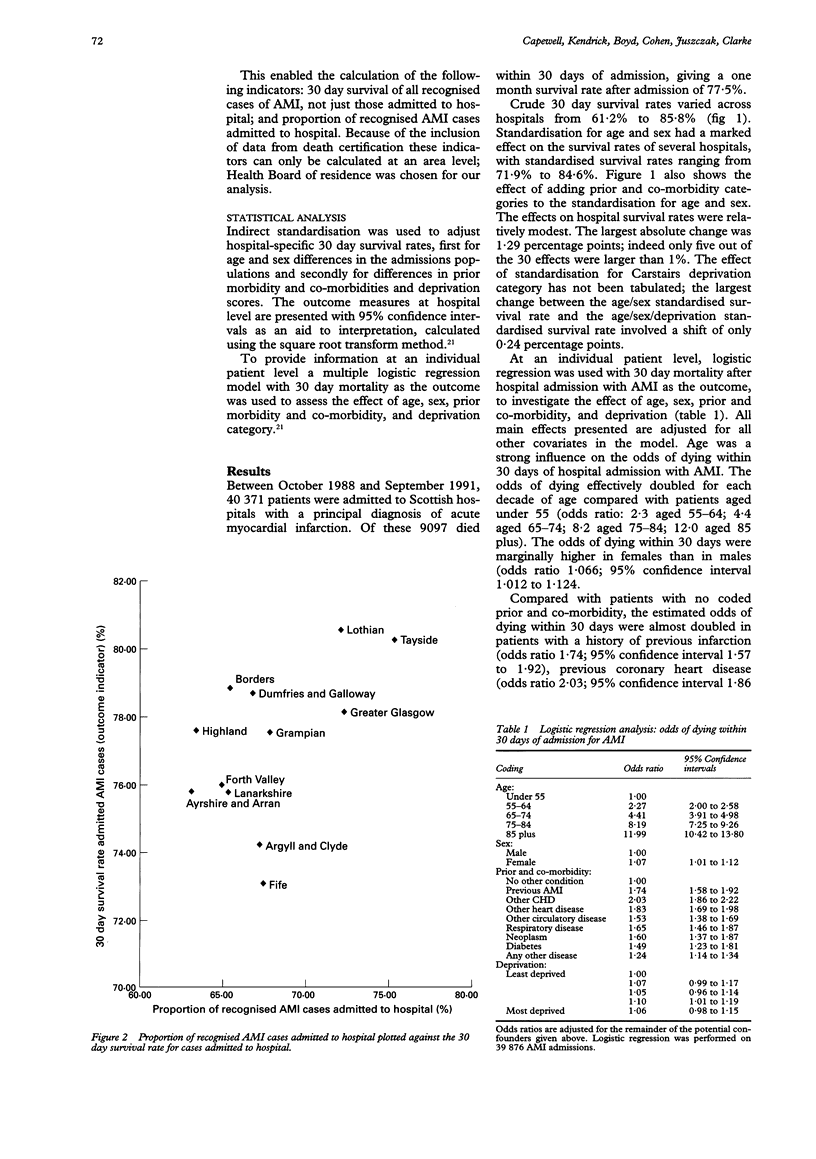

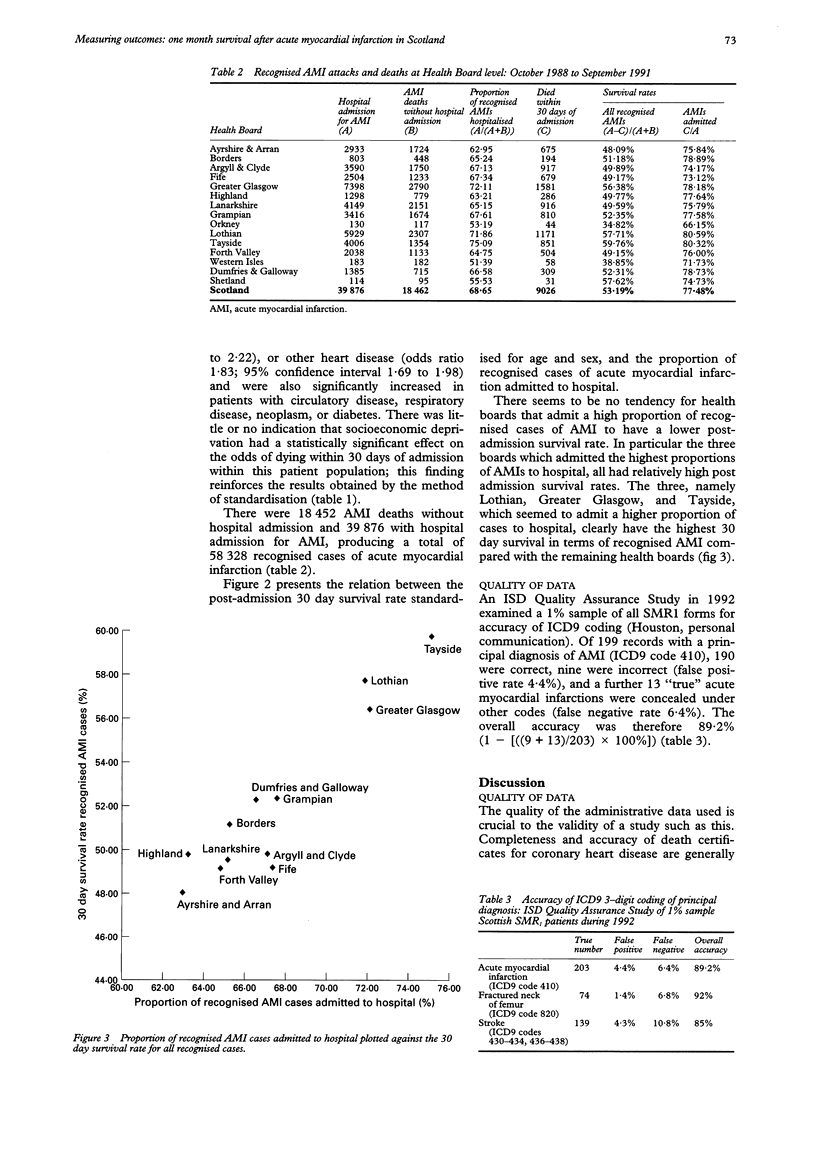

OBJECTIVE: To examine 30 day survival after acute myocardial infarction as an outcome indicator, and explore the effects of adjusting for available prognostic factors such as age, sex, co-morbidity, deprivation, and deaths outside hospital. DESIGN: Cohort study. SETTING: The Scottish Record Linkage System was analysed. This national data-base links inpatient data to death certificate information for a population of 5.1 million. SUBJECTS: All 40,371 admissions to hospital with a principal diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction, plus all 18,452 deaths outside hospital with a principal cause of death registered as acute myocardial infarction (ICD9 code 410) during 1988-1991. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES: The outcome event was death from any cause, within hospital or elsewhere, within 30 days of admission. RESULTS: During 1988-1991, 30 day survival after acute myocardial infarction was 77% in 40,371 hospital admissions, but only 53% when 18,452 acute myocardial infarction deaths in the community were included (a population-based outcome indicator with many advantages). Using logistic regression at an individual patient level, the odds of dying within 30 days effectively doubled for each decade of age (odds ratio compared with patients aged under 55: 2.3 aged 55-64, 4.4 aged 65-74, 8.2 aged 75-84, 12.0 aged 85 plus); were marginally higher in females than in males (odds ratio 1.07); were almost doubled in patients with a history of previous infarction, coronary heart disease, or other heart disease, and were also significantly increased in patients with circulatory disease, respiratory disease, neoplasm, or diabetes. Socioeconomic deprivation had no significant effect. Marked variations in survival between different hospitals and health board areas persisted, even after adjusting for the above prognostic factors. CONCLUSION: One month survival after acute myocardial infarction could be a useful means of measuring outcome of hospital care. There was important geographical variation in one month survival. These differences could be accounted for by variations in referral, admission, diagnosis, definition, and coding. These variables merit further research and local clinical audit before one month survival after acute myocardial infarction can be reliably used for detecting differences in quality of care. In addition, it would be essential to take account of infarct severity.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Colling A., Dellipiani A. W., Donaldson R. J., MacCormack P. Teesside coronary survey: an epidemiological study of acute attacks of myocardial infarction. Br Med J. 1976 Nov 13;2(6045):1169–1172. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6045.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlavitch S. A., Crow R., Burke G. L., Baxter J. Secular trends in Q wave and non-Q wave acute myocardial infarction. The Minnesota Heart Survey. Circulation. 1991 Feb;83(2):492–503. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.2.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans A. E., Patterson C. C., Mathewson Z., McCrum E. E., McIlmoyle E. L. Incidence, delay and survival in the Belfast MONICA Project coronary event register. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 1990;38(5-6):419–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick B., Watt G. C., Tunstall-Pedoe H. Potential impact of emergency intervention on sudden deaths from coronary heart disease in Glasgow. Br Heart J. 1992 Mar;67(3):250–254. doi: 10.1136/hrt.67.3.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guadagnoli E., Hauptman P. J., Ayanian J. Z., Pashos C. L., McNeil B. J., Cleary P. D. Variation in the use of cardiac procedures after acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1995 Aug 31;333(9):573–578. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508313330908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammar N., Larsen F. F., Sandberg E., Alfredsson L., Theorell T. Time trends in survival from myocardial infarction in Stockholm County 1976-1984. Int J Epidemiol. 1992 Dec;21(6):1090–1096. doi: 10.1093/ije/21.6.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton J. R., McWilliam A. Purchasing for quality: the providers' view. Purchasing care for patients with acute myocardial infarction. Qual Health Care. 1992 Mar;1(1):68–73. doi: 10.1136/qshc.1.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isles C. G., Hole D. J., Hawthorne V. M., Lever A. F. Relation between coronary risk and coronary mortality in women of the Renfrew and Paisley survey: comparison with men. Lancet. 1992 Mar 21;339(8795):702–706. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90599-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson R., Stewart A., Beaglehole R. Trends in coronary heart disease mortality and morbidity in Auckland, New Zealand, 1974-1986. Int J Epidemiol. 1990 Jun;19(2):279–283. doi: 10.1093/ije/19.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendrick S., Clarke J. The Scottish Record Linkage System. Health Bull (Edinb) 1993 Mar;51(2):72–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohli H. S., Knill-Jones R. P. How accurate are SMR1 (Scottish Morbidity Record 1) data? Health Bull (Edinb) 1992 Jan;50(1):14–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kottke T. E., Young D. T., McCall M. M. Effect of social class on recovery from myocardial infarction--a followup study of 197 consecutive patients discharged from hospital. Minn Med. 1980 Aug;63(8):590–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau J., Antman E. M., Jimenez-Silva J., Kupelnick B., Mosteller F., Chalmers T. C. Cumulative meta-analysis of therapeutic trials for myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1992 Jul 23;327(4):248–254. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199207233270406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mant J., Hicks N. Detecting differences in quality of care: the sensitivity of measures of process and outcome in treating acute myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1995 Sep 23;311(7008):793–796. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7008.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C. A., Thompson P. L., Armstrong B. K., Hobbs M. S., de Klerk N. Long-term prognosis after recovery from myocardial infarction: a nine year follow-up of the Perth Coronary Register. Circulation. 1983 Nov;68(5):961–969. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.68.5.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern P. G., Folsom A. R., Sprafka J. M., Burke G. L., Doliszny K. M., Demirovic J., Naylor J. D., Blackburn H. Trends in survival of hospitalized myocardial infarction patients between 1970 and 1985. The Minnesota Heart Survey. Circulation. 1992 Jan;85(1):172–179. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.1.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris R. M., Brandt P. W., Lee A. J. Mortality in a coronary-care unit analysed by a new coronary prognostic index. Lancet. 1969 Feb 8;1(7589):278–281. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(69)91036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näyhä S. Improved survival after acute myocardial infarction in Finland, 1974-1985. Int J Epidemiol. 1992 Feb;21(1):30–35. doi: 10.1093/ije/21.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons R. W., Jamrozik K. D., Hobbs M. S., Thompson D. L. Early identification of patients at low risk of death after myocardial infarction and potentially suitable for early hospital discharge. BMJ. 1994 Apr 16;308(6935):1006–1010. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6935.1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pears J., Alexander V., Alexander G. F., Waugh N. R. Audit of the quality of hospital discharge data. Health Bull (Edinb) 1992 Sep;50(5):356–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilote L., Califf R. M., Sapp S., Miller D. P., Mark D. B., Weaver W. D., Gore J. M., Armstrong P. W., Ohman E. M., Topol E. J. Regional variation across the United States in the management of acute myocardial infarction. GUSTO-1 Investigators. Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries. N Engl J Med. 1995 Aug 31;333(9):565–572. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508313330907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaper A. G., Pocock S. J., Walker M., Phillips A. N., Whitehead T. P., Macfarlane P. W. Risk factors for ischaemic heart disease: the prospective phase of the British Regional Heart Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1985 Sep;39(3):197–209. doi: 10.1136/jech.39.3.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith W. C., Kenicer M. B., Tunstall-Pedoe H., Clark E. C., Crombie I. K. Prevalence of coronary heart disease in Scotland: Scottish Heart Health Study. Br Heart J. 1990 Nov;64(5):295–298. doi: 10.1136/hrt.64.5.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson R., Ranjadayalan K., Wilkinson P., Roberts R., Timmis A. D. Short and long term prognosis of acute myocardial infarction since introduction of thrombolysis. BMJ. 1993 Aug 7;307(6900):349–353. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6900.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofler G. H., Muller J. E., Stone P. H., Davies G., Davis V. G., Braunwald E. Comparison of long-term outcome after acute myocardial infarction in patients never graduated from high school with that in more educated patients. Multicenter Investigation of the Limitation of Infarct Size (MILIS). Am J Cardiol. 1993 May 1;71(12):1031–1035. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90568-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udvarhelyi I. S., Gatsonis C., Epstein A. M., Pashos C. L., Newhouse J. P., McNeil B. J. Acute myocardial infarction in the Medicare population. Process of care and clinical outcomes. JAMA. 1992 Nov 11;268(18):2530–2536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]