Abstract

Objective

Carotid artery stenting (CAS) has become an alternative to carotid endarterectomy (CEA) for select patients with carotid atherosclerosis. We hypothesized that the choice of CAS vs CEA varies as a function of treating physician specialty, which would result in regional variation in the relative use of these treatment types.

Methods

We used Medicare claims (2002–2010) to calculate annual rates of CAS and CEA and examined changes by procedure type over time. To assess regional preferences surrounding CAS, we calculated the proportion of revascularizations by CAS, across hospital referral regions, defined according to the Dartmouth Atlas of Healthcare. We then examined relationships between patient factors, physician specialty, and regional use of CAS.

Results

The annual number of all carotid revascularization procedures decreased by 30% from 2002 to 2010 (3.2 to 2.3 per 1000; P = .005). Whereas rates of CEA declined by 35% during these 8 years (3.0 to 1.9 per 1000; P < .001), CAS utilization increased by 5% during the same interval (0.30 to 0.32 per 1000; P = .014). Variation in utilization of carotid revascularization varied across the Unites States, with some regions performing as few as 0.7 carotid procedure per 1000 beneficiaries (Honolulu, Hawaii) and others performing nearly 8 times as many (5.3 per 1000 in Houma, La). Variation in procedure type (CEA vs CAS) was evident as well, as the proportion of carotid revascularization procedures that were constituted by CAS varied from 0% (Casper, Wyo, and Meridian, Miss) to 53% (Bend, Ore). The majority of CAS procedures were performed by cardiologists (49% of all CAS cases), who doubled their rates of CAS during the study period from 0.07 per 1000 in 2002 to 0.15 per 1000 in 2010.

Conclusions

Variation in rates of carotid revascularization exists. Whereas rates of carotid revascularization have declined by more than 30% in recent years, utilization of CAS has increased. The proportion of all carotid revascularization procedures performed as CAS varies markedly by geographic region, and regions with the highest proportion of cardiologists perform the most CAS procedures. Evidence-based guidelines for carotid revascularization will require a multidisciplinary approach to ensure uniform adoption across specialties that care for patients with carotid artery disease.

Several randomized trials have established that carotid revascularization is an important tool for stroke prevention among patients with symptomatic carotid artery stenosis.1,2 However, for patients with asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis, who constitute roughly half of patients undergoing carotid revascularization3, many consider medical therapy alone a reasonable treatment option, particularly as nonoperative therapies for atherosclerosis have improved.4 In fact, recent studies examining trends in carotid revascularization have shown that rates of carotid endarterectomy (CEA) are decreasing, likely because of a decrease in the enthusiasm for invasive treatments in patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis.5,6

Whereas the utilization of carotid revascularization is declining, rates of carotid artery stenting (CAS) have increased despite payer-based attempts to limit utilization and controversies about its safety and effectiveness compared with CEA and medical therapy alone.5–7 After regulatory approval was issued for CAS in 2004, early reports by our group and others in 2010 suggested significant regional variation in utilization of CAS across the United States.8,9 This variation is indicative of uncertainty about (1) which patients are best treated by revascularization for carotid atherosclerosis and (2) how they should be treated—with endarterectomy or with stenting. Now, several years later, a better understanding of the extent of variation in utilization of CEA and CAS will help physicians and policymakers in directing patients toward the best treatment decisions for carotid disease. Further, a clearer description of the factors associated with different utilization patterns in CAS and CEA, such as physician specialty, will help inform payers such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, in which stakeholders are needed to best design health policy surrounding this controversial procedure.

It is our hypothesis that continued variation in the use of CAS across different regions of the United States persists and that this variation is related to physician specialty. Therefore, the current study aimed to define regional utilization of CAS and to explore the relationship between provider subspecialty and rates of CAS using Medicare claims data.

METHODS

Establishing a cohort of Medicare patients undergoing carotid revascularization

We used the Medicare Physician/Supplier Procedure Summary Master File to study all claims from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for the years 2002 to 2010. We used Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes to identify patients undergoing CEA (35301) for all years or CAS (37215, 37216) between 2005 and 2010. Before 2005, CPT codes for CAS were not available in Medicare claims data. Therefore, to determine the incidence of CAS in 2002–2004, we used a previously validated coding algorithm.6,8 First, we identified all patients with a procedure code for peripheral stent insertion and a concomitant International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis code for cerebrovascular disease to indicate that the stent was placed for cerebrovascular disease. Next, to be certain of all patients undergoing peripheral artery stenting for conditions unrelated to cerebrovascular disease, we excluded all patients with an ICD-9 diagnosis code for peripheral vascular disease in any position.

Institutional Board Review processes were waived. Informed consent was not required or obtained from individuals.

Calculating annual rates of CEA and CAS

To adjust for changes in the size of the Medicare population over time, we used the Medicare Denominator File to determine the total number of enrolled beneficiaries for each year 2002 through 2010. These data were used to calculate normalized annual rates of carotid revascularization procedures per 1000 beneficiaries during the study period. Trends over time were assessed by comparing the rates of carotid revascularization in 2002 with those in 2010 using χ2 analyses.

Defining regional variation in carotid revascularization

Similar to our previous work in 2009,8 we examined geographic variation in the rates of CEA and CAS within each of the 306 health referral regions (HRRs) as defined by the Dartmouth Atlas of Healthcare.10 Each HRR represents a distinct region containing several small health care centers and at least one tertiary care referral center. Because our preliminary analyses suggested that rates of CAS have increased over time, we examined regional variation in two ways, each using data from 2010. First, we defined crude rates of carotid revascularization (CEA plus CAS) for each HRR. Then, to explore associations between regional variation and utilization of CAS specifically, we calculated the proportion of all carotid revascularization procedures that were CAS for each HRR. Next, to examine if CAS has replaced CEA, we examined the difference between the rates of CEA and CAS per 1000 patients in 2010 compared with 2004 within each HRR. This was done using χ2 analyses. The year 2004 was chosen for comparison because this was the year CAS was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Examining trends among specialties over time

Specialty designation of physicians performing the procedure was taken from the Medicare Part B file Healthcare Provider Taxonomy Code. Designation is self-reported and does not necessarily imply subspecialty board certification. For the purposes of this study, each provider was classified as a radiologist, a cardiologist, or a surgeon using the self-designated taxonomy code. Therefore, radiologist classification includes both diagnostic and interventional radiologists and surgeon classification includes general surgeons, vascular surgeons, neurosurgeons, and cardiothoracic surgeons. Change over time among specialties was examined by comparing the rate of CAS performed by each specialty in 2002 with that in 2010. This was done using χ2 analyses.

All analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel 2010 and Stata/IC 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Tex). All tests with a P < .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Trends in carotid revascularization

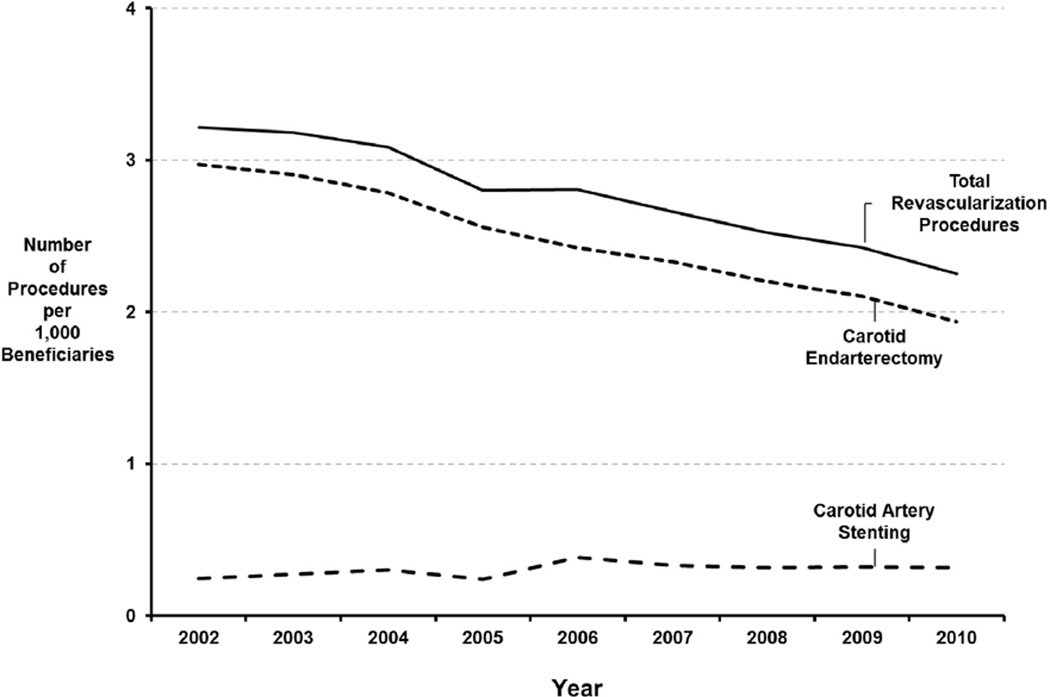

In total, data from 456,267 Medicare beneficiaries who underwent carotid revascularization between 2002 and 2010 were analyzed. The majority of these were CEA (88%). Overall, annual rates of carotid revascularization decreased by 30% over time (3.2 procedures per 1000 Medicare patients in 2002 vs 2.3 per 1000 in 2010; P < .001). This decrease is largely attributable to a decline in the number of CEAs being performed. As Fig 1 demonstrates, the annual rate of CEAs decreased 35% between 2002 and 2010 (3.0 to 1.9 CEAs per 1000 patients; P < .001). However, since its approval by the FDA in 2004, the rate of CAS has increased by 5% (0.30 vs 0.32 per 1000; P = .014).

Fig 1.

Annual rates of carotid revascularization per 1000 Medicare beneficiaries, 2002 to 2010.

The average age of patients undergoing carotid surgery over the entire study period was 75.7 years. However, this varied by procedure type, with those undergoing CAS being slightly older (75.6 years for patients undergoing CEA vs 75.8 years for those undergoing CAS; P < .001). Whereas the majority of all patients undergoing carotid revascularization were men (57%), there was a higher proportion of men undergoing CAS compared with CEA (58.5% vs 56.9%; P < .001). More than 94% of all patients undergoing carotid revascularization were white. More nonwhite patients were treated with CAS than with CEA (94.4% of patients undergoing CEA were white vs 92.5% for CAS; P < .001). Although these differences were statistically significant, this is most likely the result of a large sample size, and no clinically significant changes in patient age, sex, or race were noted over time (Table I).

Table I.

Patient demographics for those undergoing carotid endarterectomy (CEA) and carotid artery stenting (CAS) in 2002 and 2010

| 2002 |

2010 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | CEA | CAS | Total | CEA | CAS | |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 75.4 (5.8) | 75.4 (5.8) | 75.0 (5.9) | 75.7 (6.3) | 75.7 (6.2) | 75.9 (6.4) |

| Male, % | 55.8 | 56.3 | 49.4 | 57.8 | 57.5 | 59.7 |

| Race, % | ||||||

| White | 94.9 | 95.2 | 91.6 | 93.7 | 94.0 | 91.9 |

| Black | 2.9 | 2.8 | 4.8 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 4.9 |

| Other | 2.1 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 3.3 |

SD, Standard deviation.

Regional variation in carotid revascularization

In 2010, rates of carotid revascularization varied dramatically across the Unites States, with some regions performing as few as 0.7 carotid procedure per 1000 beneficiaries (Honolulu, Hawaii) and others performing nearly 8 times as many (5.3 per 1000 in Houma, La).

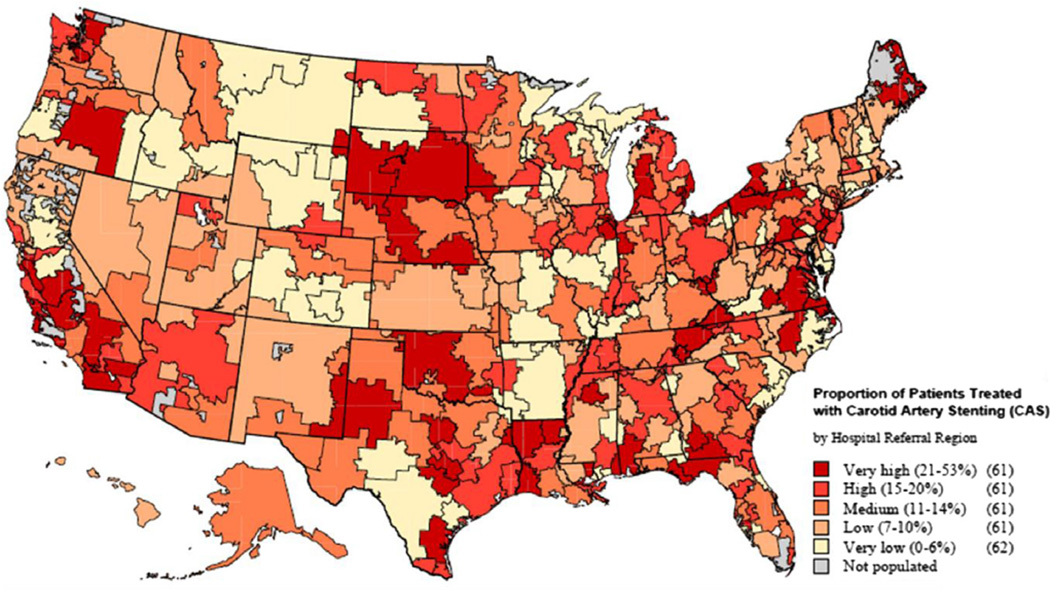

When we examined regional variation in the proportion of carotid revascularization procedures that were CAS, we found that on average, hospital referral regions used CAS 14% of the time and CEA the remaining 86%. However, this proportion varied substantially among HRRs, with some regions (Casper, Wyo, and Meridian, Miss) performing little CAS (0%), whereas others (Bend, Ore) used CAS to revascularize patients with carotid disease in more than half of cases (53%; Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Regional variation in utilization of carotid artery stenting (CAS). Variation reflects the proportion of all carotid revascularization procedures that are CAS.

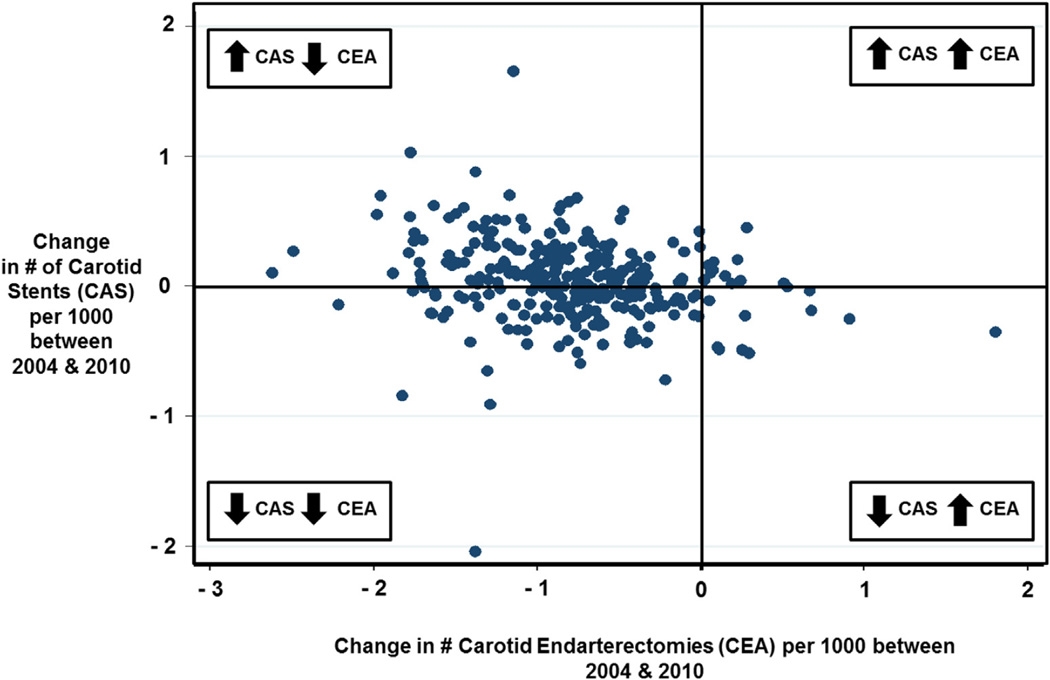

Relationship of regional rates of change in use of CEA and CAS

Next, to determine if increases in the use of CAS were related to decreases in the use of CEA, we examined the relationship between change in the rates of CEA and CAS for each region over time (Fig 3). Each point represents a single HRR. On the x-axis, we demonstrate the change in the regional rate of CEA between 2004 and 2010, and the y-axis represents the corresponding regional change in the rate of CAS during the same time period. Nearly every region decreased use of CEA (94%) between 2004 and 2010. However, fewer than half of the regions (44%) experienced a reduction in the number of CAS procedures per 1000 beneficiaries over time, and a majority of these regions had an increase in the use of CAS during that period.

Fig 3.

Change in the number of revascularizations by carotid endarterectomy (CEA; x-axis) and carotid artery stenting (CAS; y-axis) per 1000 Medicare beneficiaries performed from 2004 to 2010 for each of the 306 hospital referral regions (HRRs).

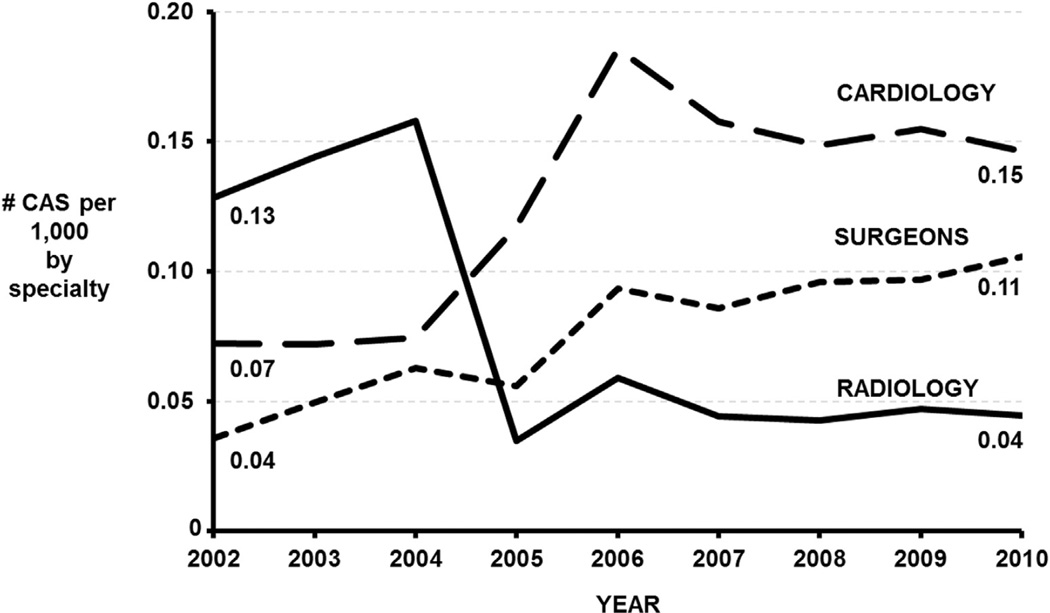

Specialty specific trends in carotid stenting

Fig 4 shows rates of CAS by specialty for each year between 2002 and 2010. Whereas the absolute number of CAS procedures remains relatively small, the rate of CAS by surgeons has nearly tripled, from 0.04 to 0.11 per 1000 beneficiaries (P < .001). Similarly, the rate of stenting by cardiologists has increased, nearly doubling between 2002 and 2010 (0.07 to 0.15 per 1000; P < .001). However, among radiologists, the use of carotid stenting has declined, from 0.13 stents per 1000 beneficiaries in 2002 to 0.04 per 1000 in 2010 (P < .001).

Fig 4.

Annual number of carotid artery stents (CAS) placed by cardiologists, surgeons, and radiologists per 1000 Medicare beneficiaries from 2002 to 2010. The change in rate from 2002 to 2010 was statistically significant for each speciality (P < .001 for each).

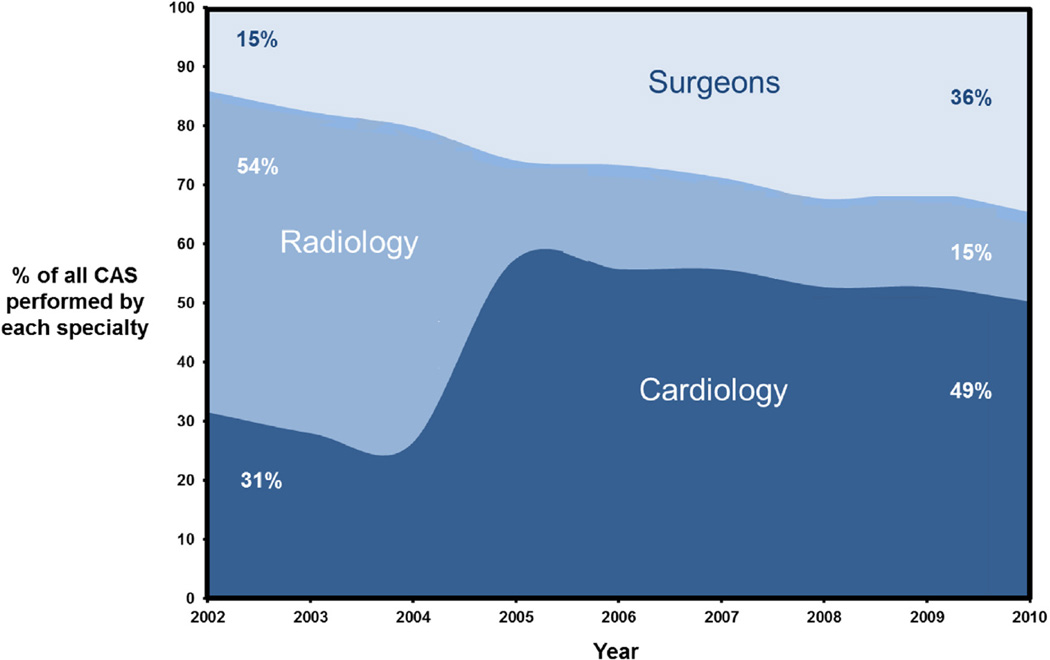

We then examined the percentage of CAS performed by each specialty. In 2002, the majority of stents (54%) were placed by radiologists and the remaining 31% and 15% by cardiologists and surgeons, respectively. However, by 2010, this distribution shifted dramatically, with carotid stenting by radiologists declining to only 15% and both cardiologists and surgeons increasing their use of stenting to account for 49% and 36% of all stents placed, respectively (Fig 5).

Fig 5.

Proportion of all carotid artery stenting (CAS) performed by surgeons, radiologists, and cardiologists for each year 2002 to 2010.

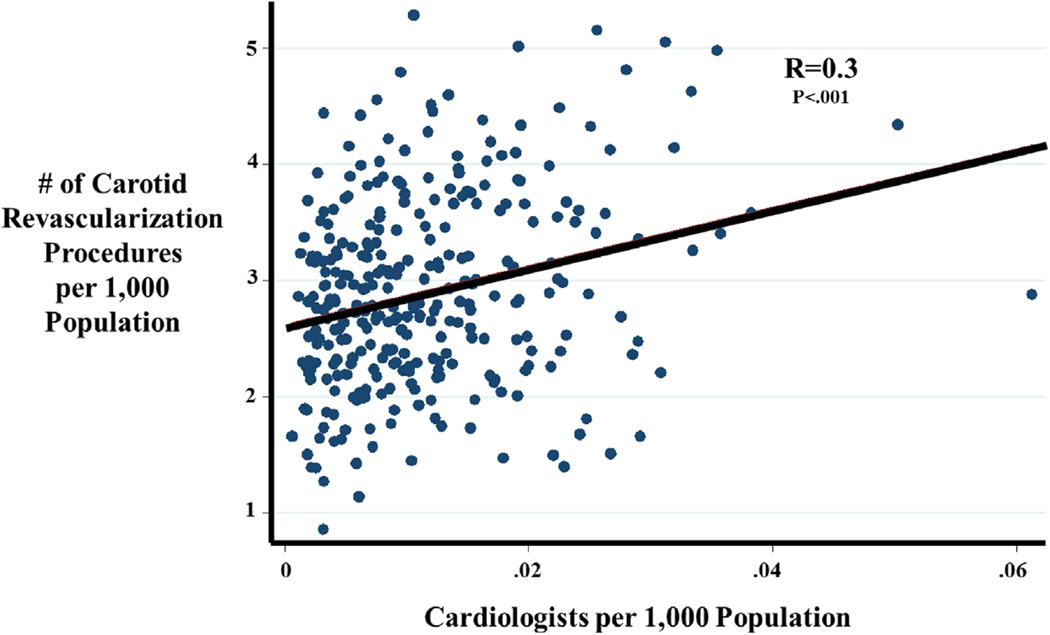

Finally, we examined the relationship between regional density of cardiologists (defined as number of cardiologists per person for each HRR) and utilization of carotid revascularization procedures. We found that carotid revascularization increases as the density of cardiologists increases (R = 0.3; P < .001; Fig 6).

Fig 6.

Relationship between utilization of carotid revascularization procedures (either endarterectomy or stenting) and number of cardiologists (each per 1000 Medicare beneficiaries). Reported by hospital referral region (HRR).

DISCUSSION

Our national study of practice patterns in Medicare patients demonstrates that annual rates of carotid revascularization have decreased by 30% between 2002 and 2010. This is attributable to a 35% decrease in the number of CEAs performed each year in Medicare patients, even while the rate of CAS has increased by 5% since 2004. Second, among those patients selected for carotid revascularization, certain regions almost never perform CAS, whereas providers in other regions use CAS for more than half of their carotid revascularization procedures. Further, provider specialty is associated with the choice of procedure type, as regions with the highest density of cardiologists more commonly choose CAS for carotid revascularization.

Utilization of carotid revascularization over time and region

Several prior studies have examined trends in utilization of CEA and CAS over time (Table II). For example, in 2012, Skerritt et al5 examined the incidence of carotid revascularization procedures using the National Inpatient Sample. This large study demonstrated a significant decline in total number of revascularization procedures performed across the country between 1998 and 2008 (26.8%; P < .0001). These authors also noted a 36% decrease in the performance of CEA and a concomitant rise in the incidence of CAS (5%; P < .001). Similarly, in 2010, Patel et al9 studied Medicare claims data from 2003 to 2006 and demonstrated a decrease in CEA over time (18.8%). This study also highlighted an increase in utilization of CAS between 2005 and 2006 (33%). Our prior work6,8 and the current study support these findings. Overall rates of carotid revascularization continue to decline since 2002, with an associated and significant (35%) drop in the rate of CEA. However, the incidence of CAS has not decreased and in fact appears to be increased since the device was first approved by the FDA in 2004.

Table II.

Summary of studies reporting trends and patterns of variation in carotid revascularization

| Author (year) |

Study years | Data source |

Change in carotid revascularization (P value) |

Change in CEA (P value) |

Change in CAS (P value) |

Regional variation findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birkmeyer (1998)11 |

1995 | Medicare | — | — | — | 10.1-fold variation in utilization of CEA across HRRs |

| Kresowik (2001)12 |

1995–1996 | Medicare in 10 states |

— | — | — | 1.5-fold variation in utilization of CEA across states (25.7–38.4 procedures per 10,000 beneficiaries) |

| Nowygrod (2006)21 |

1998–2003 | NIS | 5.3% absolute decrease (NR) |

14.9% decrease in incidence (<.001) |

116% increase in incidence (<.001) |

— |

| Goodney (2008)6 |

1998–2004 | Medicare | 11% decrease in incidence (<.02) |

17% decrease in incidence (<.01) |

149% increase in incidence (<.01) |

— |

| Goodney (2010)8 |

1998–2007 | Medicare | 18.4% decrease in incidence (<.0001) |

30.6% decrease in incidence (<.0001) |

600% increase in incidence (<.001) |

10-fold variation in utilization of CEA across HRRs in both 1998 and 2007; 6-fold variation in utilization of CAS across HRRs in 2007 |

| Patel (2010)9 |

2003–2006 | Medicare | 6.3% decrease in incidence (NR) |

18.8% decrease in incidence (NR) |

33% increase in incidence between 2005 and 2006 (NR) |

9-fold variation in utilization of CEA across HRRs in 2003–2004, decreased to 7-fold variation in 2005–2006; also demonstrated marked variation in utilization of CAS across HRRs in 2006 |

| Eslami (2011)22 |

2005–2007 | NIS | — | 90.7% of all procedures were CEA in 2005; 86% were CEA in 2006 |

9.3% of procedures were CAS in 2005; 14% were CAS in 2006 |

— |

| Nallamothu (2011)16 |

2005–2007 | Medicare |

— | — | Increase in CAS across all provider types |

Cardiologists perform 52% of all CAS; regions where cardiologists account for >50% of procedures have higher population-based utilization rates |

| Skerritt (2012)5 |

1998–2008 | NIS | 26.8% decrease in incidence (<.0001) |

36% decrease in incidence (<.001) |

5% increase in incidence (<.001) |

— |

| Dumont (2012)7 |

1998–2008 | NIS | — | 97.2% of all procedures were CEA in 1998; 87.4% were CEA in 2008 |

2.8% of all procedures were CAS in 1998; 12.6% of all procedures were CAS in 2008 |

— |

CAS, Carotid artery stenting; CEA, carotid endarterectomy; HRRs, hospital referral regions; NIS, National Inpatient Sample; NR, not reported.

Others have also examined regional variation in utilization of CEA and CAS (Table II). Before the widespread introduction of CAS, Birkmeyer et al11 and Kresowik et al12 examined variation in CEA across HRRs and a sample of states, respectively. Birkmeyer et al highlighted 10-fold variation in rates of CEA in 1995, and Kresowik confirmed in 1996 that variation persists at the state level as well, demonstrating a 1.5-fold difference in CEA utilization across the 10 sampled states. One might assume this variation would diminish in subsequent years, following completion of randomized trials providing evidence to support CEA; however, more recent studies by Goodney et al8 and Patel et al,9 both published in 2010, have shown persistent 9- to 10-fold variation in utilization of CEA across HRRs. Furthermore, each of these studies demonstrates significant regional variation in CAS as well.

Our current work informs this discussion in two important ways. First, we provide more recent data showing that the rise in CAS that was evident in 2007 continues, despite persistent decline in the rates of overall carotid revascularization and CEA. Second, our analysis suggests that variation in the choice of carotid revascularization type (CEA vs CAS) is dramatic despite recent publication of relevant clinical trials. Whereas CAS is rarely used for carotid revascularization in some regions, it accounts for more than half of carotid revascularization procedures in others, and much of this effect is related to physician specialty.

Specialty-based practice preferences

Many who have studied patterns in utilization of surgical procedures, including carotid revascularization, have hypothesized potential explanations for continued variation. The most widely accepted explanation to date is what Halm has termed the “enthusiasm” hypothesis.13 This concept originates with Wennberg’s definition of preference-sensitive care: care that “comprises treatments for conditions where legitimate treatment options exist” and is dictated by informed patients’ preferences, values, and beliefs.10 Despite the implicit patient centeredness in this type of care, variation in preference-sensitive care is largely driven by the physician, as the preference of many patients is to rely on their providers to dictate appropriate treatment. Thus, variation is the result of fluctuating enthusiasm for a treatment among providers. As Halm points out, provider enthusiasm can be driven by many things,13 and the current study suggests that provider specialty is a strong contributor.

Enthusiasm for CAS is a controversial topic. Cardiologists and interventionalists have led efforts to extend funding for CAS,14 whereas surgeons and neurologists have exercised caution in expanding the approval of CAS outside of clinical trials and registries, especially in asymptomatic patients.15 Our specialty-associated findings are similar to those reported by Nallamothu et al,16 who examined physician specialty in CAS for the years 2005–2007. These authors found that the majority of carotid stents are placed by cardiologists for asymptomatic disease and that HRRs where cardiologists performed the majority of stenting were also more likely to be high utilization than others (4.3 CAS procedures per 10,000 enrollees in regions where cardiologists place >50% of all stents vs 2.5 per 10,000 in regions where cardiologists place <25% of stents).

Professional societies interested in generating guidelines across specialties for the use of CAS have found, at best, limited success. The heterogeneous approaches used to identify candidates for CEA and CAS have made it difficult to find agreeable approaches. Multidisciplinary studies, such as the recently approved National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke-funded Carotid Revascularization for Primary Prevention of Stroke (CREST-2) trial,17 are necessary not only to discern best practice evidence but also to build the requisite collaborations that allow a uniform approach in choosing the right procedure for the right patient, regardless of the provider’s specialty type. CREST-2 is a double-armed multicenter, randomized trial of carotid revascularization and intensive medical management vs medical management alone in patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis. One arm of the trial will randomize patients to CEA vs no CEA, and the second arm will randomize patients to CAS vs no CAS. Medical management will be uniform for all treatment groups. This trial, along with a clear understanding of regional practice patterns in utilization of carotid revascularization, provides important information to support shared decision-making for both patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis and their providers.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, this study uses administrative data, the weaknesses of which are well described and include (1) the implicit dependence on accurate coding for reliable analyses, particularly for the years 2002–2004, when CAS was identified by a unique coding algorithm as a CPT for CAS was not yet in existence, and (2) the inability to completely capture clinically relevant data pertaining to patient factors such as comorbidities, symptom status, and degree of carotid stenosis. However, the current study represents a descriptive analysis of “real-world” use of carotid revascularization procedures, and the degree of variation demonstrated in the current study is too large to be explained by differences in these patient factors alone. Second, provider specialty designation is self-reported and does not necessarily imply subspecialty board certification. However, this classification scheme is widely used and accepted throughout the literature.16,18,19 Third, Medicare claims data pertaining to the utilization of CEA and CAS after 2010 were not examined for the current study. However, the data presented reflect important nationwide trends in the practice of carotid revascularization that according to more recent discharge data from the National Inpatient Sample appear to persist beyond the time frame of this study. In 2010, the National Inpatient Sample documented 90,914 discharges after CEA and only 426 national discharges for CAS. However, by 2012, the number of CEAs performed had decreased even further to 81,400 (an 11% decline), and CAS remains on the rise (1195, nearly a 3-fold increase).20 Finally, the current study does not examine outcomes to support the assumption that variation is detrimental or to indicate whether high utilization regions are overusing CAS or, on the contrary, low utilization regions are underusing CAS. Important postprocedural outcomes are difficult to assess using claims data, and therefore our future work will aim to examine this using a linked clinical claims database.

CONCLUSIONS

Annual rates of carotid revascularization have decreased markedly since 2002. This is due to a decrease in the number of CEAs performed annually. However, despite payer-based attempts to limit utilization of CAS and controversies about its safety and effectiveness compared with CEA and medical therapy alone, rates of CAS continue to increase over time. The majority of CAS procedures are performed by cardiologists, with persistent regional variation in the proportion of all carotid revascularization constituted by CAS. Future studies are needed to define which practices are the most beneficial and cost-effective for patients who will benefit from carotid revascularization, and these findings need to be disseminated across all providers who treat patients with carotid artery stenosis.

Acknowledgments

P.P.G. was supported by a K08 Award (K08 HL05676) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and an SVS Foundation Lifeline Award.

Footnotes

Author conflict of interest: none.

The editors and reviewers of this article have no relevant financial relationships to disclose per the JVS policy that requires reviewers to decline review of any manuscript for which they may have a conflict of interest.

Presented at the Thirty-eighth Annual Spring Meeting of the Peripheral Vascular Surgery Society, San Francisco, Calif, May 30–June 1, 2013.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: JW, JC, PG

Analysis and interpretation: JW, BN, DS, RP, JB, JC, PG

Data collection: BN, DS, RP, JB, JC, PG

Writing the article: JW

Critical revision of the article: JW, BN, DS, RP, JB, JC, PG

Final approval of the article: JW, BN, DS, RP, JB, JC, PG

Statistical analysis: JW, PG

Obtained funding: Not applicable

Overall responsibility: PG

REFERENCES

- 1.Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:445–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108153250701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study. JAMA. 1995;273:1421–1428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnett HJ, Eliasziw M, Meldrum HE, Taylor DW. Do the facts and figures warrant a 10-fold increase in the performance of carotid endarterectomy on asymptomatic patients? Neurology. 1996;46:603–608. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.3.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spence JD. Asymptomatic carotid stenosis: mainly a medical condition. Vascular. 2010;18:123–126. doi: 10.2310/6670.2010.00023. discussion: 127–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skerritt MR, Block RC, Pearson TA, Young KC. Carotid endarterectomy and carotid artery stenting utilization trends over time. BMC Neurol. 2012;12:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodney PP, Lucas FL, Travis LL, Likosky DS, Malenka DJ, Fisher ES. Changes in the use of carotid revascularization among the medicare population. Arch Surg. 2008;143:170–173. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2007.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dumont TM, Rughani AI. National trends in carotid artery revascularization surgery. J Neurosurg. 2012;116:1251–1257. doi: 10.3171/2012.3.JNS111320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodney PP, Travis LL, Malenka D, Bronner KK, Lucas FL, Cronenwett JL, et al. Regional variation in carotid artery stenting and endarterectomy in the Medicare population. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:15–24. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.864736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel MR, Greiner MA, DiMartino LD, Schulman KA, Duncan PW, Matchar DB, et al. Geographic variation in carotid revascularization among Medicare beneficiaries, 2003–2006. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1218–1225. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wallaert JB, De Martino RR, Finlayson SR, Walsh DB, Corriere MA, Stone DH, et al. Carotid endarterectomy in asymptomatic patients with limited life expectancy. Stroke. 2012;43:1781–1787. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.650903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Birkmeyer JD, Sharp SM, Finlayson SR, Fisher ES, Wennberg JE. Variation profiles of common surgical procedures. Surgery. 1998;124:917–923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kresowik TF, Bratzler D, Karp HR, Hemann RA, Hendel ME, Grund SL, et al. Multistate utilization, processes, and outcomes of carotid endarterectomy. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33:227–234. doi: 10.1067/mva.2001.111881. discussion: 234–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halm EA. The good, the bad, and the about-to-get ugly: national trends in carotid revascularization: comment on “Geographic variation in carotid revascularization among Medicare beneficiaries, 2003–2006”. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1225–1227. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White CJ, Jaff MR. Catch-22: carotid stenting is safe and effective (Food and Drug Administration) but is it reasonable and necessary (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services)? JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:694–696. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbott AL, Adelman MA, Alexandrov AV, Barber PA, Barnett HJ, Beard J, et al. Why calls for more routine carotid stenting are currently inappropriate: an international, multispecialty, expert review and position statement. Stroke. 2013;44:1186–1190. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nallamothu BK, Lu M, Rogers MA, Gurm HS, Birkmeyer JD. Physician specialty and carotid stenting among elderly medicare beneficiaries in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1804–1810. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. [Accessed May 13, 2015];Carotid Revascularization for Primary Prevention of Stroke (CREST-2) Available at: http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/clinical_trials/NCT02089217.htm.

- 18.Goodney PP, Beck AW, Nagle J, Welch HG, Zwolak RM. National trends in lower extremity bypass surgery, endovascular interventions, and major amputations. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Axelrod DA, Fendrick AM, Birkmeyer JD, Wennberg DE, Siewers AE. Cardiologists performing peripheral angioplasties: impact on utilization. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4:191–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Accessed July 15, 2015];Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/ [PubMed]

- 21.Nowygrod R, Egorova N, Greco G, Anderson P, Gelijns A, Moskowitz A, et al. Trends, complications, and mortality in peripheral vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:205–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eslami MH, McPhee JT, Simons JP, Schanzer A, Messina LM. National trends in utilization and postprocedure outcomes for carotid artery revascularization 2005 to 2007. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.08.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]