Abstract

Total pancreatectomy with islet auto-transplantation (TPIAT) may relieve the pain of chronic pancreatitis while avoiding post-surgical diabetes. Minimizing hyperglycemia after TPIAT limits beta cell apoptosis during islet engraftment. Closed loop (CL) therapy combining an insulin pump with a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) has never previously been investigated in islet transplant recipients. Our objective was to determine the feasibility and efficacy of CL therapy to maintain glucose profiles close to normoglycemia following TPIAT. Fourteen adult subjects (36% male; age 35.9±11.4 years) were randomized to subcutaneous insulin via CL pump (n=7) or multiple daily injections with blinded CGM (n=7) for 72 hours at transition from IV to subcutaneous insulin. Mean serum glucose values were significantly lower in the CL pump than the control group (111±4 v. 130±13 mg/dL; p=0.003 without increased risk for hypoglycemia (% time <70 mg/dl: CL pump 1.9%, control 4.8%, p=0.46). Results from this pilot study suggest that CL therapy is superior to conventional therapy in maintaining euglycemia without increased hypoglycemia. This technology shows significant promise to safely maintain euglycemic targets during the period of islet engraftment following islet transplantation. (clinicaltrials.gov #: NCT01945138)

INTRODUCTION

Islet transplantation is a promising therapy to restore or preserve endogenous beta cell function in type 1 diabetes (allogenic islet transplantation) or after surgical pancreatectomy (auto-islet transplantation). Emerging diabetes therapies are often divided into the groups of (1) immune or cell-based therapies including islet transplantation and medications to modulate cell-mediated immunity, or (2) technological therapies utilizing continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) pumps, continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), and engineering that combines CSII and CGM to create a mechanical artificial pancreas (AP). To date, cell-based therapies have rarely been paired with advances in diabetes technology. However, these two new areas of research are not mutually exclusive, and may even be complementary.

Following allogenic or autologous islet infusion, islets are initially stripped of their native blood supply and are reliant on diffusion of nutrients and oxygen to the islet core until neovascularization is complete, a process that may take weeks to months (1, 2). During this engraftment period, the transplanted islets are especially vulnerable to overstimulation by hyperglycemia in an anoxic environment, which contributes to beta-cell loss (3, 4).

Extensive preclinical and limited clinical data suggest that hyperglycemia increases beta-cell apoptosis, while maintenance of euglycemia reduces the number of islets necessary to prevent post-surgical diabetes (5–11). In the immediate post-operative period, intravenous continuous insulin infusion therapy is the standard of care and it is relatively easy to successfully achieve a narrow range of euglycemia (12). After several days, however, the patient must be transitioned to subcutaneous insulin therapy, and it becomes more challenging to maintain strict euglycemia without risk of hypoglycemia. During this vulnerable period, closed loop (CL) artificial pancreas technology may offer an opportunity to improve early post-transplant glycemic outcomes, and thereby improve the engraftment of the newly transplanted islets via reduced hyperglycemic stress on the devascularized islet graft. The success of islet allotransplantation for type 1 diabetes is impacted by immune factors such as auto- or alloimmunity, and by the potential for beta-cell toxicity of common immunosuppressive agents. In contrast, islet auto-transplantation in patients with chronic pancreatitis (CP) undergoing total pancreatectomy with Islet Auto-Transplantation (TPIAT) because of intractable pain (13–15) is not subject to auto- or alloimmune interference and there is no need for anti-rejection drugs.

Thus, studying new applications of diabetes technology in TPIAT recipients provides a unique “non-immune” setting allowing for the isolated refinement of techniques to improve islet engraftment and survival with the potential to ultimately benefit both patients with CP and patients with type 1 diabetes (16). Current research on CL pump therapy in type 1 diabetes demonstrates an overall common theme of successful glycemic control, particularly overnight when activity and unannounced meals are absent, with blood glucose (BG) values in target range 70–100% of the time (17). Based on these observations, we postulated that CL pump technology would allow near normal glycemic control early after TPIAT, when patients are on a continuous enteral nutrition feeding regimen. The present study randomized adult TPIAT patients to standard insulin therapy or 72 hours of CL pump therapy using Medtronic’s ePID (external physiological insulin delivery) 2.0 controller modified with specific parameters for the post-TPIAT patient population (18–20), with a base Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) controller and an additional term for insulin feedback (IFB) previously described in detail by Ruiz et al. (18). We hypothesized that CL pump technology would permit safely targeting lower mean blood glucose values while minimizing the occurrence of hypoglycemia associated with aggressive insulin therapy, during the time when patients transitioned from intravenous to subcutaneous insulin therapy.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Patient Population

Participants in this pilot study for efficacy and feasibility of CL pump therapy after TPIAT were adult (age 21–64y), non-diabetic patients with chronic pancreatitis scheduled for TPIAT at the University of Minnesota between February 2014 and March 2015. Patients with pre-existing diabetes mellitus by American Diabetes Association criteria, those who required acetaminophen or corticosteroids, and those with significant psychiatric disease or developmental delay impacting ability to provide informed consent were excluded.

The clinical trial was approved by the University of Minnesota (UMN) Investigational Review Board (IRB, #1307M37923); informed consent was obtained from all participants. As the study involves the use of an investigational device, an IDE was obtained from the United States Food and Drug Agency (FDA, #G130178). The study is registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01945138).

Randomization

Participants were block randomized 1:1 at the time of TPIAT surgery to receive subcutaneous insulin via either closed loop insulin pump (CL pump arm) or by multiple daily injections (control arm, standard-of-care). A computer based random number generator was used to generate random number schedules.

Total Pancreatectomy and Islet Auto-Transplantation Procedure

All participants underwent total pancreatectomy consisting of partial duodenectomy, Roux-en-Y duodenojejunostomy, choledochojejunostomy, and splenectomy as previously described (12, 21, 22). Isolation and purification of the patient’s own islet cells was performed in the UMN Molecular and Cellular Therapeutics Good Manufacturing Practices Facility. Using a pressure-controlled pump system, the pancreas was distended with cold enzyme solution (23). The pancreas was then digested using the semi-automated method described by Ricordi (24). The islets were infused into a tributary of the portal vein, or if elevated portal pressures prevented infusion of all the islets intraportally, the remaining islets were transplanted into the peritoneal cavity.

Immediately after surgery all patients were started on a continuous intravenous (IV) insulin infusion protocol (IIP) with the goal of maintaining bedside glucometer BG in the range of 80–125 mg/dL. As per the standar d management protocol for TPIAT recipients at our institution, patients had no oral intake after surgery or during the subsequent study period due to post-surgical gastroparesis; all nutrition was delivered by continuous enteral feeds administered via a jejunal tube. IV insulin was discontinued and subcutaneous insulin started once patients reach full enteral nutrition (generally 4–8 days after surgery).

Subcutaneous Insulin Investigational Period

Participants began their 72 hour study period of conventional multiple daily insulin injections (MDI) vs CL pump therapy at the time of transition from IV insulin to subcutaneous therapy. Participants randomized to the control arm received multiple daily insulin injections per standard post-TPIAT care as directed by the primary endocrinology team, without influence or input by the research team. This consisted of a basal insulin analog (glargine) administered once or twice daily, and rapid-acting insulin (aspart) every 4 hours as needed when blood glucose was above target range of 80–125 mg/dL; starting doses were estimated based on daily IV insulin needs, and therapy was then adjusted daily to achieve target range. To collect comparison data from the control group, during the 72 hour study period, trained study staff obtained YSI reference serum glucose values every 4 hours, and daily morning paired C-peptide and glucose levels. Control participants wore 2 blinded CGM devices (1 primary and 1 backup; iPro2). YSI performed glucose analysis provided serum glucose values and the continuous glucose monitors provided sensor glucose values.

Participants randomized to the experimental arm (CL pump group) received SQ insulin as directed by the Medtronic ePID 2.0 Control Tool system. Participants in this group wore a Medtronic Paradigm REAL-Time Insulin pump loaded with insulin aspart as well as two Enlite 2 Glucose Sensors attached to MiniLink REAL-Time Transmitters. Sensor glucose levels were calculated based on a calibration factor estimated from a linear regression of plasma glucose and filtered sensor current with a fixed sensor delay time of 10 minutes to account for delayed glucose shifts between the intravenous and interstitial compartments (25, 26). The PID portion of the controller then used a series of equations to determine the insulin requirements for a given minute based on the sensor data in a “treat-to-target” fashion with the target being set at either 110 or 100 mg/dL. Initial controller settings were determined by the Medtronic PID Gains Calculator, which was modified specifically for the post-TPIAT population, using daily totals and hourly rates of IV insulin prior to transition.

During the 72 hour investigational period participants in the CL pump group had their SQ insulin infusion rate adjusted every minute based on the control tool algorithm. During this time period all insulin dosing decisions for the experimental group were determined by the algorithm. CGM sensors were recalibrated for 2 values in a row with an absolute relative difference (ARD) between YSI and CGM reading of ≥20% or one value with an ARD of ≥30%. Serum glucose values were obtained every 30 minutes or more frequently as required by the safety protocol. Insulin rate, sensor glucose values and serum glucose values were presented in real-time on the Control Tool software for review by trained study staff. Every four hours serum glucose by YSI at predefined time points were used for comparison statistics with the control group, to avoid bias of having more frequent glucose assessments in the CL pump group. Paired C-peptide and glucose levels were obtained each morning. At the end of the investigational period, CGM data was extracted from the Control Tool for analysis.

Data Analysis

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at UMN (27). All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (Cary, NC).

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or as percentage (95% confidence interval), except where otherwise noted. Hypothesis testing was conducted using two-sided Student’s t-test with equal variance. Values of p ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant. Area under the curve (AUC) for CGM analysis of experimental and control patients was determined via Riemann sums method with width of 5 and 1 minutes, respectively. Analysis for confounding and effect modification was conducted using multiple least-squares linear regression.

RESULTS

Patient Population, Demographics, and Pre-Transplant History

Twenty-one patients met initial recruitment criteria and were consented for possible study participation (Figure 1). Of these, 7 were not subsequently started on the study protocol due to canceled surgery in 2, only partial completion of surgical procedure in 2, post-surgery complications in 2 and withdrawal of consent in 1. Of the 14 patients who met inclusion and exclusion criteria at the time of SQ transition, 7 were randomized to the experimental arm and 7 were randomized to the control arm.

Figure 1.

Recruitment Flow Chart

Enrolled patients consisted of 5 men and 9 women with an average age of 35.9±11.4 years. Demographic and pre-transplant characteristics were not significantly different between the two study groups (Table 1). Overall transplanted islet mass was good when compared to other TPIAT studies (28) (5432±2983 islet equivalents per kilogram body weight (IEq/kg)) and did not differ between groups. One patient in the MDI group and two patients in the CL group received a portion of their islets in the peritoneal cavity. The time between surgery and SQ transition (days on intravenous insulin drip) was about 2 days shorter for the CL pump group than for the control group (5.1±1.1 days v. 6.9±1.1 days; p=0.011). Average meter BG did not differ between the MDI and CL groups for the intravenous insulin drip period (117±6 v. 114±4 mg/dL; p=0.270).

Table 1.

Demographic and Baseline Patient Characteristics

| Control Group | CL pump Group | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 33.1 ± 13.3 | 38.6 ± 9.4 | 0.394 |

| Sex M/F (% male) | 4/3 (57%) | 1/6 (14%) | 0.109 |

| Wt at Tx (kg) | 76.7 ± 23.7 | 66.1 ± 10.3 | 0.298 |

| BMI at Tx (kg/m2) | 24.9 ± 5.7 | 25.3 ± 4.5 | 0.899 |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | 5.4 ± 0.5 | 5.1 ± 0.2 | 0.132 |

| Fasting Serum Glucose (mg/dL) | 95 ± 13 | 89 ± 6 | 0.308 |

| Fasting C-peptide (ng/mL) | 3.0 ± 3.7 | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 0.543 |

| Peak MMTT C-peptide (ng/mL) | 5.8 ± 4.4 | 6.4 ± 2.2 | 0.740 |

| Islet mass (IEq/kg) | 4245 ± 2174 | 6619 ± 3357 | 0.142 |

| Intraportal (IEq/kg) | 4047 ± 1767 | 5930 ± 2577 | 0.137 |

| Intraperitoneal (IEq/kg) | 199 ± 525 | 689 ± 1423 | 0.409 |

| Days on Insulin Drip (days) | 6.9 ± 1.1 | 5.1 ± 1.1 | 0.011 * |

| BG on Insulin Drip (mg/dL) | 117 ± 6 | 114 ± 4 | 0.270 |

| Primary Etiology of CP | |||

| Identified Genetic Mutation (PRSS1, SPINK1, CFTR) | 1 (14%) | 3 (43%) | |

| Mechanical Dysfunction | |||

| (Pancreatic Divisum, Sphincter of Oddi Dysfunction, Annular Pancreas) | 4 (57%) | 3 (43%) | |

| Idiopathic Pancreatitis | 2 (29%) | 1 (14%) |

indicates statistical significance with p < 0.05;

Abbreviations: yrs=years, Wt=weight, Tx=Transplant, BG=Blood Glucose, MMTT=Mixed Meal Tolerance Test, IEq=Islet Equivalents, CP=Chronic Pancreatitis

Mean serum glucose and variability in CL pump vs control groups

During the 72 hour investigational period, mean serum glucose was significantly lower in the CL pump group than in the control group (111±4 mg/dL v. 130±13 mg/dL; p=0.003; Table 2). When assessed by individual patients, the highest patient’s average serum glucose in the CL pump group was lower than the lowest control group patient’s average serum glucose (Figure 2). The standard deviation for serum glucose for the CL pump group trended lower than that for the control group (14.1±3.3 mg/dL v. 21.0±10.2 mg/dL; p=0.12), but did not reach statistical significance in this pilot study.

Table 2.

Group Comparison for 72h Investigational Period

| Control Group | CL pump Group | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum Glucose Avg (mg/dL) | 130 ± 13 | 111 ± 4 | 0.003 * |

| Serum Glucose StDev (mg/dL) | 21.0 ± 10.2 | 14.1 ± 3.3 | 0.115 |

| Sensor Glucose Avg (mg/dL) | 125 ± 20 | 114 ± 4 | 0.193 |

| Sensor Glucose StDev (mg/dL) | 21.0 ± 10.3 | 20.1 ± 5.1 | 0.848 |

| % in Range 70–140 mg/dL (%) | 70.6 (48.0, 93.1) | 89.2 (83.5, 94.8) | 0.074 |

| Hypoglycemia | |||

| AUC < 70 mg/dL (min*mg/dL/day) | 1615 ± 4267 | 146 ± 270 | 0.381 |

| % < 70 mg/dL (%) | 4.8 (−6.9, 16.6) | 1.1 (−0.3, 2.6) | 0.461 |

| Hyperglycemia | |||

| AUC > 140 mg/dL (min*mg/dL/day) | 7860 ± 11444 | 2025 ± 1177 | 0.205 |

| % > 140 mg/dL (%) | 23.7 (1.5, 46.0) | 9.7 (4.9, 14.5) | 0.157 |

| AM C-Peptide Avg (ng/mL) | 1.6 ± 1.0 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 0.443 |

| TDD of Insulin (U/kg/day) | 0.56 ± 0.31 | 0.26 ± 0.17 | 0.040 * |

indicates statistical significance with p < 0.05;

Abbreviations: BG=Blood Glucose, Avg=Average, StDev=Standard Deviation, AUC=Area Under the Curve, TDD=Total Daily Dose

Figure 2.

Serum Glucose Values by Patient and Study Group. Large circle denotes mean, box denotes 25th percentile, median and 75th percentile and small circles denote outliers.

Time spent in hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia based on continuous glucose monitoring

The Area Under the Curve analysis from CGM suggested a trend towards fewer values for the CL pump group compared to the control group for hyperglycemia (AUC>140 mg/dL: 2025±1177 min*mg/dL/day v. 7860±11444 min*mg/dL/day; p=0.205). There was a trend towards significant difference between groups in time spent in target range; the CL pump group was in the target range of 70–140 mg/dL 89.2 % (83.5, 94.8) of the time and the control group was in range 70.6% (48.0, 93.1) of the time (p=0.074).

Improved glycemia was not associated with increased risk for hypoglycemia in the CL pump group, an important safety consideration with more aggressive glycemic control. Hypoglycemia AUC <70 mg/dl was 146±270 min*mg/dL/day for the CL group v. 1615±4267 min*mg/dL/day for controls, p=0.381. Similarly, percent time spent with glucose < 70 mg/dl was 1.1% for the CL group and 4.8% for the control group, p=0.46. While neither the differences in hyperglycemia nor hypoglycemia measures were statistically significant, within this pilot study the trend was in the hypothesized direction.

Morning C-peptide levels were similar between the two groups during this study period. The total daily insulin dose required in the CL pump group was significantly lower than in the control group (0.26±0.17 v. 0.56±0.31; p=0.040).

Analysis for Confounders and Effect Modifiers

For the four a priori defined endpoints of mean serum glucose, standard deviation of serum glucose, sensor glucose AUC in hypoglycemia and sensor glucose AUC in hyperglycemia, additional analyses were conducted to investigate for possible confounding or effect modification.

First, because the number of days on the IV insulin drip (days from surgery to study start) was significantly less in the CL pump group, this raised concern for the possibility of this factor as a potential confounder for the differences observed between the 2 groups. Multiple least-squares regression analyses conducted to evaluate the relationship between days on drip and study group effects on the 4 primary endpoints indicated that the number of days on insulin drip prior to transition had no effect on the study outcomes.

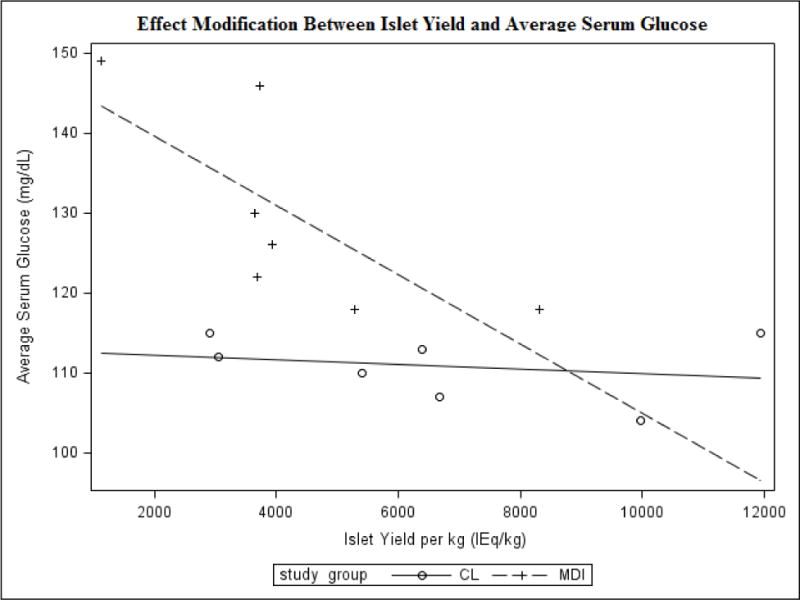

Second, due to the importance of islet mass on insulin secretion and glycemic regulation we hypothesized that the number of islets transplanted may be an effect modifier for glucose control outcomes. Islet mass was thus included in a multiple least-squares regression analysis looking at the relationship between islet mass (IEq/kg) and study group effects on the 4 primary endpoints. Islet mass was significantly inversely associated with mean serum glucose (p=0.018), standard deviation in serum glucose (p=0.034), and sensor glucose AUC in hyperglycemia (p=0.016). Islet mass had no effect on sensor glucose AUC in hypoglycemia (p=0.8).

Of particular interest, we observed an interaction between the study group assignment and the islet mass transplanted. Specifically, islet mass transplanted had a marked effect on glycemic outcomes in the control group, but minimal impact in the CL pump group. The covariance plots illustrate that within the control group only, higher islet mass transplanted correlated with lower average serum glucose (Figure 3, p-value for interaction term of islet mass-treatment assignment p=0.03). Similar interactions were observed between treatment assignment and islet mass transplanted for the outcomes of sensor glucose AUC in hyperglycemia (p=0.014) and standard deviation in serum glucose (p=0.08).

Figure 3.

Multiple Least-Squares Linear Regression Analysis for Effect Modification

Safety Analysis

No participants in either group experienced a severe adverse event. No participants required withdrawal from the investigational protocol for safety concerns. One participant in the control group experienced a grade 2 event of seizure without hypoglycemia. This was determined by the primary team to be a reaction to narcotic medications used for post-surgery pain control. One participant in the control group experienced 2 episodes of symptomatic hypoglycemia with serum glucose values in the 50–60 mg/dL range that resolved with IV dextrose. Two participants in the CL pump group each experienced one episode of asymptomatic hypoglycemia documented in the 50–60 mg/dL range that resolved with IV dextrose; in review, both events appear to be related to incorrect device calibration.

CONCLUSIONS

Success of islet engraftment is heavily dependent on maintenance of narrow-range euglycemia in the post-transplant period. Closed loop insulin pump systems have never previously been used in islet transplant populations but have been shown to maintain narrow-range euglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes. This study aimed to assess the efficacy and feasibility of a CL system in patients after TPIAT. To our knowledge, this is the first study to ever pair islet cell replacement therapy and closed loop pump technology. Overall the results from this efficacy and feasibility pilot study support the effectiveness and safety of CL systems to improve glycemic control in the TPIAT population in the post-transplant period.

The major goal of insulin therapy in the post-transplant period is to limit dysglycemia during the immediate post-transplant period. Dysglycemia is the combined effect of hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia, and glycemic variability. Overall the CL pump system was very effective in controlling serum glucose in a narrow range after TPIAT, more so than conventional standard of care. This system allowed a lower mean serum glucose and increased percent time in a near-normal glycemic range, without increasing hypoglycemia, when compared to conventional MDI therapy.

Islet mass transplanted is a critical predictor in the success of islet auto- or allo-transplantation (16), but survival and engraftment of these transplanted islets is likely to be equally important albeit more difficult to assess. With improved post-transplant immunosuppressive strategies and improved islet harvesting techniques, successful reversal of diabetes has improved in both forms of islet transplantation, with similar islet function observed (29). Improved islet survival through reduced post-transplant dysglycemia also holds significant promise to improve outcomes in both autoislet transplantation for chronic pancreatitis and alloislet transplantation for type 1 diabetes (30).

The overall effect of CL therapy was demonstrated in this study to be successful in reducing hyperglycemia with likely reduction in glycemic variability without adversely increasing hypoglycemia. The overall time spent in the target blood glucose range compares favorably with other studies using closed loop systems in healthy outpatient type 1 diabetes patients during overnight or fasting conditions. O’Grady and colleagues recently utilized a similar PID system overnight in 8 patients with T1DM and found 84.5% time in target range of 70–144 mg/dL (31). Elleri and colleagues used a MPC system overnight in patients with T1DM and found 82% time in target range of 71–145 mg/dL (32).

The time from surgery to SQ conversion (days on insulin drip) was significantly shorter for the CL group than for the control group. This was likely attributable to the conversion process being driven by the experimental team in the CL group and by the endocrine service in the control group. In our clinical observation, glucose levels are more labile in the immediate post-operative period than farther out due to greater physical stress, more severe pain, and variable GI absorption of feeds. For these reasons, we postulate that any bias from the CL pump group transitioning to subcutaneous insulin earlier should bias the results towards the null hypothesis, and statistical analysis with multiple least squares regression did not suggest this as a confounder of outcomes. In fact, this may represent a clinical advantage to use of a CL pump therapy, since with the CL pump, we were able to confidently convert immediately to subcutaneous therapy once goal enteral feeds were reached; in contrast with standard MDI therapy, it is conventional to observe a patient for a full day on goal-rate enteral feeds in order to calculate insulin needs and ensure that feeds are tolerated.

Sub-analysis for the treatment groups showed a striking effect modification based on islet mass transplanted. For the CL group, islet mass transplanted had little effect on mean serum glucose, serum glucose standard deviation, or AUC in hyperglycemia, whereas for the control group, a lower islet mass transplanted was associated with higher values for these 3 glycemic markers. We postulate that in the CL group more aggressive and rapidly adaptable continuous insulin therapy was able to maintain near normo-glycemia, allowing for significant islet cell rest, and thus a lack of variation based on islet cell yield. In contrast, the control group receiving intermittent insulin therapy may have had to rely more on endogenous insulin production from transplanted islets to handle variations in glycemia; in this situation, patients with greater transplanted islet mass would be better able to control glucose fluctuations in the short-term, but the lack of beta cell rest might ultimately endanger engraftment and long-term success of the surgery.

Participants in this study continue in long-term follow up; C-peptide levels from two and four weeks post-transplant did not show any apparent functional differences between groups (Table 3). However, we consider it unlikely that only 3 days of improved glycemic control, though both clinically and statistically significant in magnitude, would produce observable improvements in long term islet function. While such a study has never been conducted previously in islet transplant patients, this hypothesis is based on the limited findings from the Buckingham “metabolic study” which did not show improved beta-cell survival with intensive CL therapy shortly after diagnosis of type 1 diabetes (33). However, type 1 diabetes with ongoing immune-driven beta cell loss is a very different setting than cell transplantation; in autologous cell transplant or appropriately immunosuppressed allogenic islet cell transplant, there is a markedly more hypoxic islet environment, and hyperglycemia is likely to be a bigger contributing factor to beta cell loss than in the setting of new onset type 1 diabetes. Thus, the potential for benefit with longer duration CL pump therapy is likely greater in the cell transplant setting.

Table 3.

Follow Up Visit Data

| Control Group | Experimental Group | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 14 Post-TPIAT (n=14) | |||

| BG (mg/dL) | 135 ± 81 | 108 ± 16 | 0.4012 |

| C-peptide (ng/mL) | 1.0 ± 0.9 | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 0.2208 |

| Day 28 Post-TPIAT (n=14) | |||

| BG (mg/dL) | 113 ± 29 | 100 ± 21 | 0.3258 |

| C-Peptide (ng/mL) | 1.0 ± 1.2 | 1.7 ± 1.2 | 0.3116 |

These results add to a growing body of research combining new technologies with cell replacement therapy. Much of this research has focused on micro- or nano-encapsulation technologies to protect islets from immunity, or engineered bioscaffolds to increase vascularlization and islet survival (34–37). Artificial CL systems represent a new potential technology application to the islet transplant field. Currently, feasibility of long-term implementation of CL pump therapy in islet transplantation is limited by the investigational nature of such devices and need for high intensity inpatient monitoring. At this stage of device development, 30 min serum glucose sampling, constant supervision by a trained medical provider, and manual sensor recalibrations several times daily are required for use. However, we expect that as the sensor-pump technologies advance, CL pump therapy may present a real option for longer duration use in TPIAT and other cell transplant settings. Next generation CGM sensors are advertised as being more stable and requiring fewer recalibrations. The transmitters for these sensors will also communicate with low energy Bluetooth rather than RF signals, further reducing missed communication errors. The current CL pump system appeared to be safe overall, with no SAEs and minimal hypoglycemia.

This study was conducted in adult patients undergoing TPIAT; although we postulate that these findings are relevant to other forms of cell replacement therapy for type 1 diabetes, we acknowledge that the findings from this pilot study may have limited generalizability to other post- transplant populations. The overall islet mass transplanted in both study groups was relatively high (5432±2983 IEq/kg) and this may limit conclusions about glycemic control as it pertains to patients receiving lower islet mass. Although the total number of patients in this study (14 overall with 7 in each group) compares favorably with other initial device studies, and serves as an initial exploration of the efficacy, feasibility and safety of CL systems in patients after TPIAT, a larger sample size would likely improve the significance and generalizability of the findings. Future directions include the use of more advanced AP systems in a larger number of patients (including children), for a longer duration, and on an outpatient basis with less intensive monitoring. In such work use an impartial secondary CGM device (e.g. the new FreeStyle Libre) in both subject populations may be beneficial to more equally compare continuous glucose endpoints between groups.

Conclusions

CL insulin pump systems are a valuable emerging tool for narrow range glycemic control in patients requiring insulin therapy. This technology was shown in this study to provide some statistically and clinically significant improvements in glycemic parameters in adults after total pancreatectomy with islet auto-transplantation without producing associated increased episodes of hypoglycemia or adverse events. Further work in this area is necessary to validate and expand upon these findings. Continued improvements in CL pump systems, notably in CGM devices, will be essential towards moving this technology from experimentally effective to clinically feasible. This technology has the ability to provide essential islet cell rest after transplantation and may play a role in long term islet survival.

Acknowledgments

G.F wrote the manuscript, designed the study, conducted the clinical research, and acquired data. M.B. contributed to writing the manuscript, reviewed/edited the manuscript, designed the study, conducted the clinical research, and acquired data. B.N. and A.M. designed the study and reviewed/edited the manuscript. T.D, G.B., and T.P. conducted the surgeries, reviewed/edited the manuscript, and acquired data. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose except as described below regarding funding for this project.

Funding for this study was provided by the Vikings Children’s Research Fund and the Clinical Translational Sciences Institute (CTSI) pilot study award at the University of Minnesota. Medtronic Diabetes provided supplies as part of investigator initiated grant. The UMN CTSI is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Award Number UL1TR000114. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The authors would like to thank our patients for participation in this project. We would also like to acknowledge the dedicated support of the research nursing staff, in particular Marnee Brandenberg and Nancee Nichols; and the dedicated medical staff on hospital units 4D and 7A. We would also like to thank Martin Cantwell and Dr. Natalie Kurtz from Medtronic who developed the custom algorithm for this study and provided teaching and training on the experimental device, James Hodges who provided guidance on statistical analysis, Dr. Sriram Sankaranarayanan who provided instruction and review of control systems theory and Dr. Stuart Weinzimer who assisted with the FDA IDE master file.

Abbreviations

- TPIAT

total pancreatectomy with islet auto-transplantation

- CP

chronic pancreatitis

- CL

closed loop

- CGM

continuous glucose monitor

- CSII

continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion

- AP

artificial pancreas

- ePID

external physiological insulin delivery

- UMN

University of Minnesota

- FDA

Food and Drug Agency

- IIP

insulin infusion protocol

- MDI

multiple daily injections

- ARD

absolute relative difference

- AUC

area under the curve

- CTSI

clinical translational sciences institute

References

- 1.Hathout E, Chan NK, Tan A, Sakata N, Mace J, Pearce W, et al. In vivo imaging demonstrates a time-line for new vessel formation in islet transplantation. Pediatric transplantation. 2009;13(7):892–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2008.01088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Speier S, Nyqvist D, Cabrera O, Yu J, Molano RD, Pileggi A, et al. Noninvasive in vivo imaging of pancreatic islet cell biology. Nature medicine. 2008;14(5):574–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finzi G, Davalli A, Placidi C, Usellini L, La Rosa S, Folli F, et al. Morphological and ultrastructural features of human islet grafts performed in diabetic nude mice. Ultrastructural pathology. 2005;29(6):525–33. doi: 10.1080/01913120500323563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nacher V, Merino JF, Raurell M, Soler J, Montanya E. Normoglycemia restores beta-cell replicative response to glucose in transplanted islets exposed to chronic hyperglycemia. Diabetes. 1998;47(2):192–6. doi: 10.2337/diab.47.2.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biarnes M, Montolio M, Nacher V, Raurell M, Soler J, Montanya E. Beta-cell death and mass in syngeneically transplanted islets exposed to short- and long-term hyperglycemia. Diabetes. 2002;51(1):66–72. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davalli AM, Scaglia L, Zangen DH, Hollister J, Bonner-Weir S, Weir GC. Vulnerability of islets in the immediate posttransplantation period. Dynamic changes in structure and function. Diabetes. 1996;45(9):1161–7. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.9.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Juang JH, Bonner-Weir S, Wu YJ, Weir GC. Beneficial influence of glycemic control upon the growth and function of transplanted islets. Diabetes. 1994;43(11):1334–9. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.11.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jimbo T, Inagaki A, Imura T, Sekiguchi S, Nakamura Y, Fujimori K, et al. A novel resting strategy for improving islet engraftment in the liver. Transplantation. 2014;97(3):280–6. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000437557.50261.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merino JF, Nacher V, Raurell M, Biarnes M, Soler J, Montanya E. Optimal insulin treatment in syngeneic islet transplantation. Cell transplantation. 2000;9(1):11–8. doi: 10.1177/096368970000900102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrer-Garcia JC, Merino-Torres JF, Perez Bermejo G, Herrera-Vela C, Ponce-Marco JL, Pinon-Selles F. Insulin-induced normoglycemia reduces islet number needed to achieve normoglycemia after allogeneic islet transplantation in diabetic mice. Cell transplantation. 2003;12(8):849–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellin MD, Sutherland DE, Chinnakotla S, Dunn T, Kim Y, Johnson J, et al. Insulin Independence After Islet Autotransplant is Associated with Sublte Differences in Early Post-Transplant Glycemic Control. Diabetes. 2012 Jun;61(Supplement 1):A43. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forlenza GP, Chinnakotla S, Schwarzenberg SJ, Cook M, Radosevich DM, Manchester C, et al. Near-euglycemia can be achieved safely in pediatric total pancreatectomy islet autotransplant recipients using an adapted intravenous insulin infusion protocol. Diabetes technology & therapeutics. 2014;16(11):706–13. doi: 10.1089/dia.2014.0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yadav D, Timmons L, Benson JT, Dierkhising RA, Chari ST. Incidence, prevalence, and survival of chronic pancreatitis: a population-based study. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2011;106(12):2192–9. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steer ML, Waxman I, Freedman S. Chronic pancreatitis. The New England journal of medicine. 1995;332(22):1482–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506013322206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muniraj T, Aslanian HR, Farrell J, Jamidar PA. Chronic pancreatitis, a comprehensive review and update. Part II: Diagnosis, complications, and management. Disease-a-month : DM. 2015;61(1):5–37. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robertson RP. Islet transplantation for type 1 diabetes, 2015: what have we learned from alloislet and autoislet successes? Diabetes care. 2015;38(6):1030–5. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah VN, Shoskes A, Tawfik B, Garg SK. Closed-loop system in the management of diabetes: past, present, and future. Diabetes technology & therapeutics. 2014;16(8):477–90. doi: 10.1089/dia.2014.0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruiz JL, Sherr JL, Cengiz E, Carria L, Roy A, Voskanyan G, et al. Effect of insulin feedback on closed-loop glucose control: a crossover study. Journal of diabetes science and technology. 2012;6(5):1123–30. doi: 10.1177/193229681200600517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steil GM, Rebrin K, Darwin C, Hariri F, Saad MF. Feasibility of automating insulin delivery for the treatment of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2006;55(12):3344–50. doi: 10.2337/db06-0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weinzimer SA, Steil GM, Swan KL, Dziura J, Kurtz N, Tamborlane WV. Fully automated closed-loop insulin delivery versus semiautomated hybrid control in pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes using an artificial pancreas. Diabetes care. 2008;31(5):934–9. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bellin MD, Sutherland DE. Pediatric islet autotransplantation: indication, technique, and outcome. Current diabetes reports. 2010;10(5):326–31. doi: 10.1007/s11892-010-0140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farney AC, Najarian JS, Nakhleh RE, Lloveras G, Field MJ, Gores PF, et al. Autotransplantation of dispersed pancreatic islet tissue combined with total or near-total pancreatectomy for treatment of chronic pancreatitis. Surgery. 1991;110(2):427–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lakey JR, Warnock GL, Ao Z, Shapiro AM, Korbutt G, Kneteman N, et al. Intraductal collagenase delivery into the human pancreas using syringe loading or controlled perfusion. Transplantation proceedings. 1998;30(2):359. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(97)01306-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ricordi C, Lacy PE, Scharp DW. Automated islet isolation from human pancreas. Diabetes. 1989;38(Suppl 1):140–2. doi: 10.2337/diab.38.1.s140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basu A, Dube S, Veettil S, Slama M, Kudva YC, Peyser T, et al. Time lag of glucose from intravascular to interstitial compartment in type 1 diabetes. Journal of diabetes science and technology. 2015;9(1):63–8. doi: 10.1177/1932296814554797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basu A, Dube S, Slama M, Errazuriz I, Amezcua JC, Kudva YC, et al. Time lag of glucose from intravascular to interstitial compartment in humans. Diabetes. 2013;62(12):4083–7. doi: 10.2337/db13-1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of biomedical informatics. 2009;42(2):377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chinnakotla S, Radosevich DM, Dunn TB, Bellin MD, Freeman ML, Schwarzenberg SJ, et al. Long-term outcomes of total pancreatectomy and islet auto transplantation for hereditary/genetic pancreatitis. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2014;218(4):530–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bellin MD, Sutherland DE, Beilman GJ, Hong-McAtee I, Balamurugan AN, Hering BJ, et al. Similar islet function in islet allotransplant and autotransplant recipients, despite lower islet mass in autotransplants. Transplantation. 2011;91(3):367–72. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318203fd09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rickels MR, Liu C, Shlansky-Goldberg RD, Soleimanpour SA, Vivek K, Kamoun M, et al. Improvement in beta-cell secretory capacity after human islet transplantation according to the CIT07 protocol. Diabetes. 2013;62(8):2890–7. doi: 10.2337/db12-1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Grady MJ, Retterath AJ, Keenan DB, Kurtz N, Cantwell M, Spital G, et al. The use of an automated, portable glucose control system for overnight glucose control in adolescents and young adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes care. 2012;35(11):2182–7. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elleri D, Allen JM, Biagioni M, Kumareswaran K, Leelarathna L, Caldwell K, et al. Evaluation of a portable ambulatory prototype for automated overnight closed-loop insulin delivery in young people with type 1 diabetes. Pediatric diabetes. 2012;13(6):449–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2012.00903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buckingham B, Beck RW, Ruedy KJ, Cheng P, Kollman C, Weinzimer SA, et al. Effectiveness of early intensive therapy on beta-cell preservation in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes care. 2013;36(12):4030–5. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coronel MM, Stabler CL. Engineering a local microenvironment for pancreatic islet replacement. Current opinion in biotechnology. 2013;24(5):900–8. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robles L, Storrs R, Lamb M, Alexander M, Lakey JR. Current status of islet encapsulation. Cell transplantation. 2014;23(11):1321–48. doi: 10.3727/096368913X670949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weir GC. Islet encapsulation: advances and obstacles. Diabetologia. 2013;56(7):1458–61. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2921-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang EY, Kronenfeld JP, Stabler CL. Engineering biomimetic materials for islet transplantation. Current diabetes reviews. 2015;11(3):163–9. doi: 10.2174/1573399811666150317130440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]