Abstract

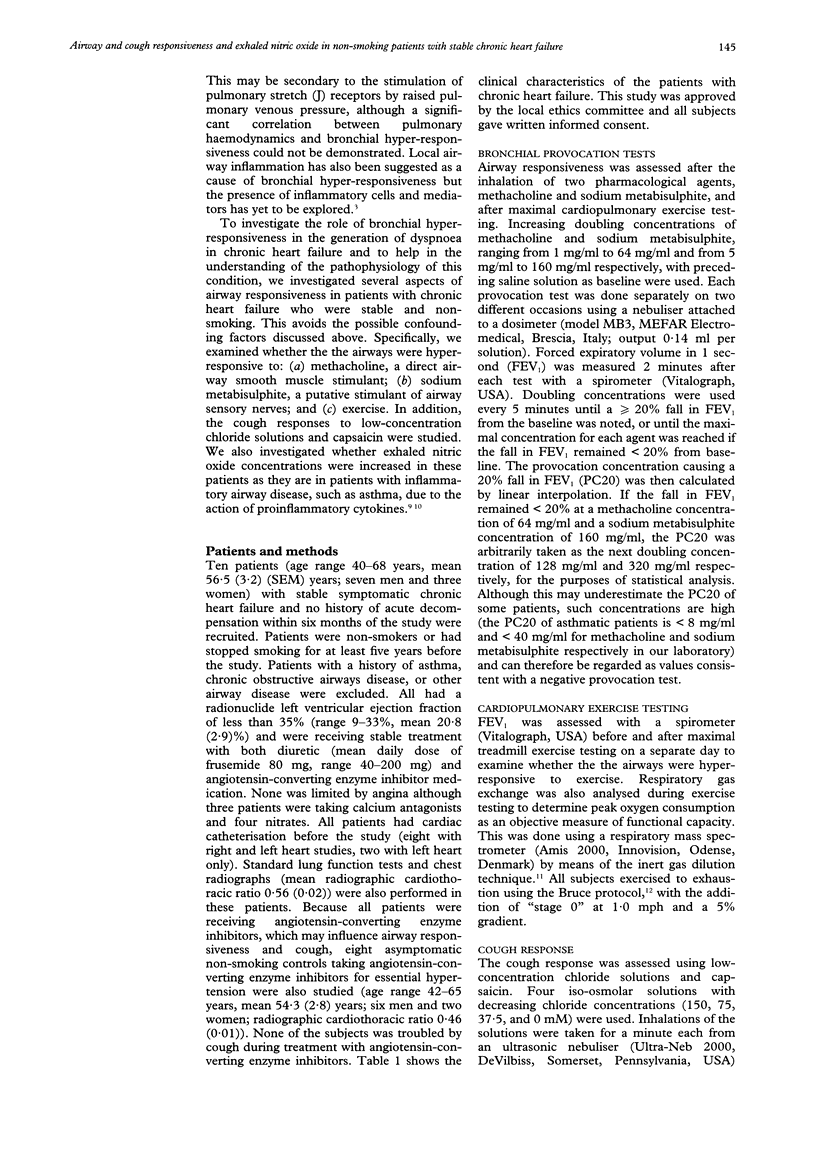

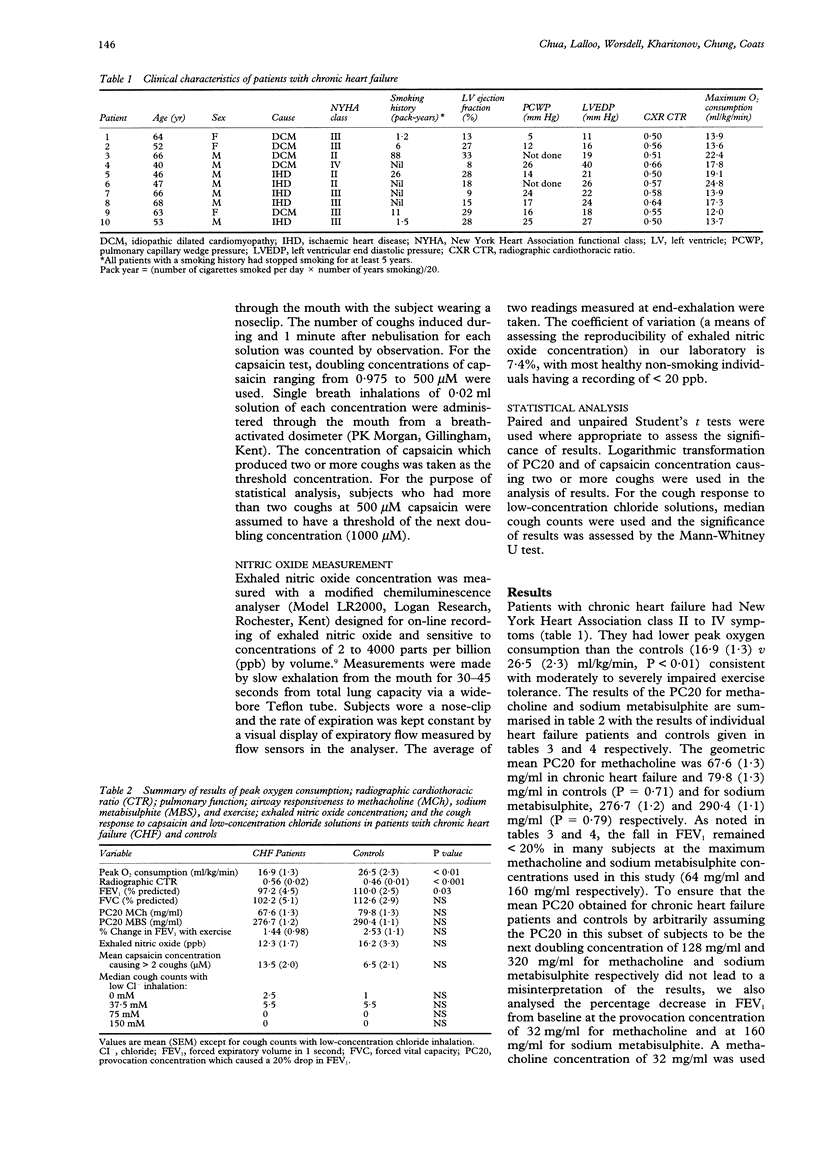

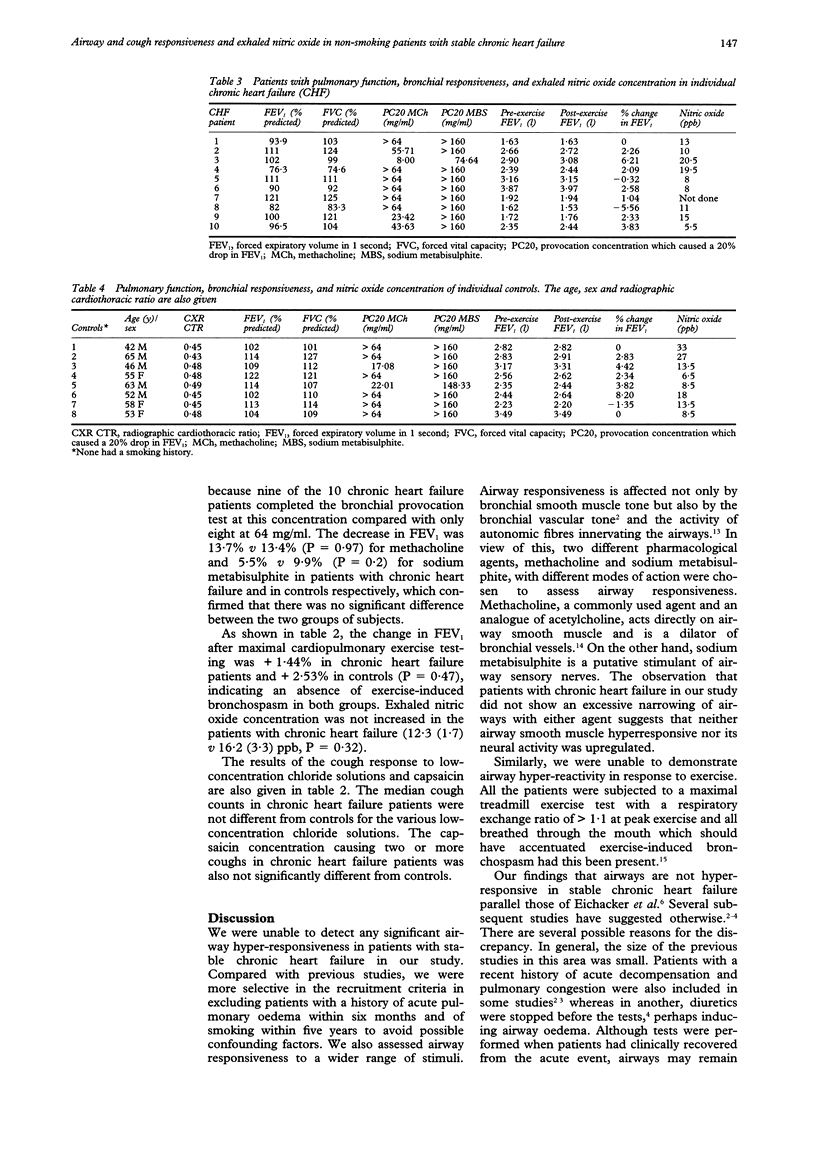

OBJECTIVE: To investigate the airway and cough responsiveness in non-smoking patients with stable chronic heart failure. Cough and wheeze, features associated with hyper-responsive airways, are not uncommon especially in decompensated chronic heart failure. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness has previously been demonstrated in chronic heart failure but this may have been confounded by smoking and acute decompensation. DESIGN: Case-control study. SETTING: Tertiary specialist hospital. PATIENTS AND INTERVENTIONS: Airway responsiveness to methacholine (a direct stimulant of smooth muscle in the airways), sodium metabisulphite (a putative stimulant of airway sensory nerves), and exercise was examined in 10 non-smoking patients with stable chronic heart failure (age 56.5 (3.2) (SEM) years; 7 men; radionuclide left ventricular ejection fraction 20.8 (2.9)%; radiographic cardiothoracic ratio 0.56 (0.02)). Exhaled nitric oxide, a product of the action of proinflammatory cytokines, was also measured to assess the contribution of local inflammation to airway responsiveness. The cough responses to low-concentration chloride solutions and to capsaicin were studied. Because all patients were receiving angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, which may influence airway responsiveness and cough, 8 asymptomatic non-smoking controls taking angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors for essential hypertension were also studied (age 54.3 (2.8) years; 6 men; radiographic cardiothoracic ratio 0.46 (0.01)). RESULTS: The mean provocative concentration that induced a 20% decrease in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) was 67.6 v 79.8 mg/ml (P = 0.71) for methacholine and 276.7 v 290.4 mg/ml (P = 0.79) for sodium metabisulphite in chronic heart failure patients and controls respectively. The change in FEV1 after maximal cardiopulmonary exercise testing was +1.44% in patients and +2.53% in controls (P = 0.47), indicating that there was no exercise-induced bronchospasm in either group (peak oxygen consumption was 16.9 (1.3) v 26.5 (2.3) ml/kg/min respectively, P < 0.01). Exhaled nitric oxide concentration was not increased in chronic heart failure (12.3 (1.7) v 16.2 (3.3) ppb, P = 0.32). The median cough counts after nebulised 0 mM and 37.5 mM chloride solutions were 2.5 v 1.0 (P = 0.6) and 5.5 v 5.5 (P = 0.5) respectively and the capsaicin concentration causing two or more coughs was 13.5 v 6.5 microM (P = 0.5). CONCLUSION: Airway hyper-responsiveness is not a predominant feature in non-smoking patients with stable chronic heart failure treated with, and tolerant to, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. It is unlikely to contribute to the exertional dyspnoea seen in these patients.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

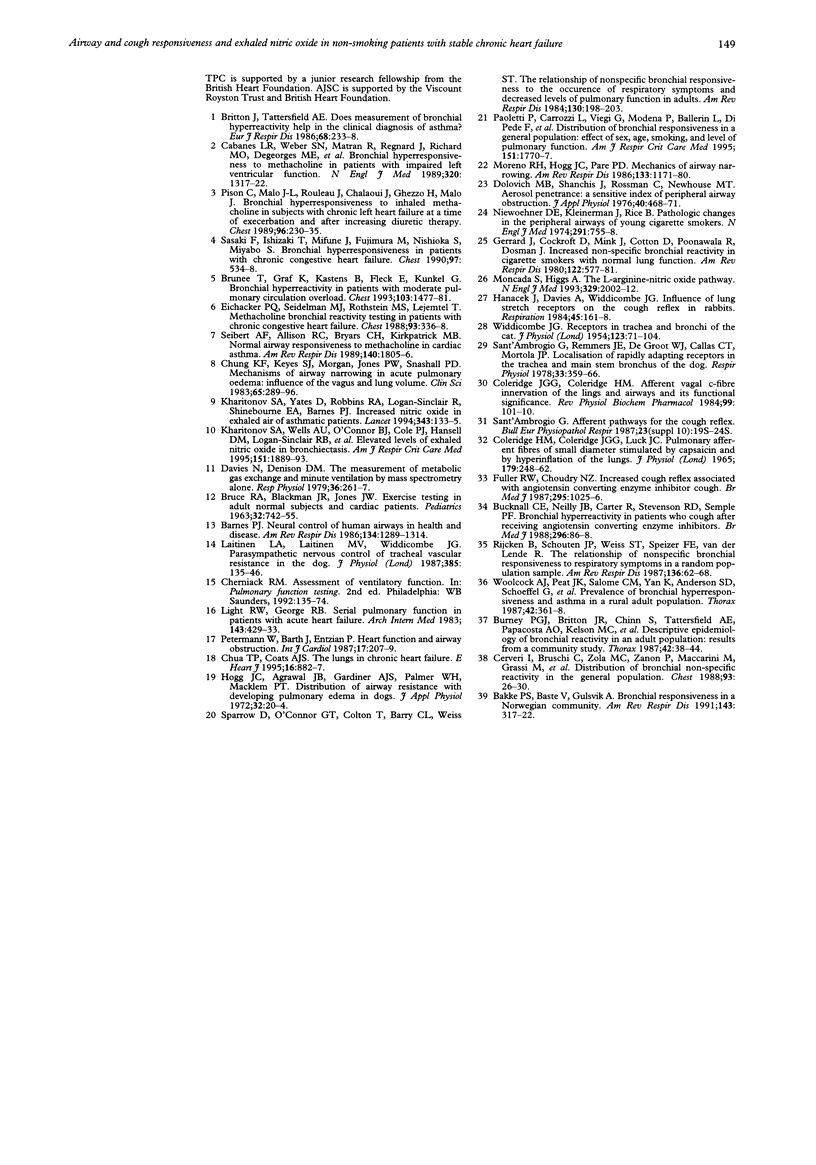

- BRUCE R. A., BLACKMON J. R., JONES J. W., STRAIT G. EXERCISING TESTING IN ADULT NORMAL SUBJECTS AND CARDIAC PATIENTS. Pediatrics. 1963 Oct;32:SUPPL–756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakke P. S., Baste V., Gulsvik A. Bronchial responsiveness in a Norwegian community. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991 Feb;143(2):317–322. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes P. J. Neural control of human airways in health and disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986 Dec;134(6):1289–1314. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.134.5.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton J., Tattersfield A. E. Does measurement of bronchial hyperreactivity help in the clinical diagnosis of asthma? Eur J Respir Dis. 1986 Apr;68(4):233–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunnée T., Graf K., Kastens B., Fleck E., Kunkel G. Bronchial hyperreactivity in patients with moderate pulmonary circulation overload. Chest. 1993 May;103(5):1477–1481. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.5.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burney P. G., Britton J. R., Chinn S., Tattersfield A. E., Papacosta A. O., Kelson M. C., Anderson F., Corfield D. R. Descriptive epidemiology of bronchial reactivity in an adult population: results from a community study. Thorax. 1987 Jan;42(1):38–44. doi: 10.1136/thx.42.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabanes L. R., Weber S. N., Matran R., Regnard J., Richard M. O., Degeorges M. E., Lockhart A. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness to methacholine in patients with impaired left ventricular function. N Engl J Med. 1989 May 18;320(20):1317–1322. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198905183202005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerveri I., Bruschi C., Zoia M. C., Zanon P., Maccarini L., Grassi M., Rampulla C. Distribution of bronchial nonspecific reactivity in the general population. Chest. 1988 Jan;93(1):26–30. doi: 10.1378/chest.93.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua T. P., Coats A. J. The lungs in chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 1995 Jul;16(7):882–887. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a061019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung K. F., Keyes S. J., Morgan B. M., Jones P. W., Snashall P. D. Mechanisms of airway narrowing in acute pulmonary oedema in dogs: influence of the vagus and lung volume. Clin Sci (Lond) 1983 Sep;65(3):289–296. doi: 10.1042/cs0650289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleridge H. M., Coleridge J. C., Luck J. C. Pulmonary afferent fibres of small diameter stimulated by capsaicin and by hyperinflation of the lungs. J Physiol. 1965 Jul;179(2):248–262. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1965.sp007660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies N. J., Denison D. M. The measurement of metabolic gas exchange and minute volume by mass spectrometry alone. Respir Physiol. 1979 Feb;36(2):261–267. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(79)90029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolovich M. B., Sanchis J., Rossman C., Newhouse M. T. Aerosol penetrance: a sensitive index of peripheral airways obstruction. J Appl Physiol. 1976 Mar;40(3):468–471. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1976.40.3.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichacker P. Q., Seidelman M. J., Rothstein M. S., Lejemtel T. Methacholine bronchial reactivity testing in patients with chronic congestive heart failure. Chest. 1988 Feb;93(2):336–338. doi: 10.1378/chest.93.2.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller R. W., Choudry N. B. Increased cough reflex associated with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor cough. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987 Oct 24;295(6605):1025–1026. doi: 10.1136/bmj.295.6605.1025-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard J. W., Cockcroft D. W., Mink J. T., Cotton D. J., Poonawala R., Dosman J. A. Increased nonspecific bronchial reactivity in cigarette smokers with normal lung function. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980 Oct;122(4):577–581. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1980.122.4.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanácek J., Davies A., Widdicombe J. G. Influence of lung stretch receptors on the cough reflex in rabbits. Respiration. 1984;45(3):161–168. doi: 10.1159/000194614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg J. C., Agarawal J. B., Gardiner A. J., Palmer W. H., Macklem P. T. Distribution of airway resistance with developing pulmonary edema in dogs. J Appl Physiol. 1972 Jan;32(1):20–24. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1972.32.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharitonov S. A., Wells A. U., O'Connor B. J., Cole P. J., Hansell D. M., Logan-Sinclair R. B., Barnes P. J. Elevated levels of exhaled nitric oxide in bronchiectasis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995 Jun;151(6):1889–1893. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.6.7767536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharitonov S. A., Yates D., Robbins R. A., Logan-Sinclair R., Shinebourne E. A., Barnes P. J. Increased nitric oxide in exhaled air of asthmatic patients. Lancet. 1994 Jan 15;343(8890):133–135. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90931-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laitinen L. A., Laitinen M. V., Widdicombe J. G. Parasympathetic nervous control of tracheal vascular resistance in the dog. J Physiol. 1987 Apr;385:135–146. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light R. W., George R. B. Serial pulmonary function in patients with acute heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 1983 Mar;143(3):429–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncada S., Higgs A. The L-arginine-nitric oxide pathway. N Engl J Med. 1993 Dec 30;329(27):2002–2012. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno R. H., Hogg J. C., Paré P. D. Mechanics of airway narrowing. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986 Jun;133(6):1171–1180. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.133.6.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niewoehner D. E., Kleinerman J., Rice D. B. Pathologic changes in the peripheral airways of young cigarette smokers. N Engl J Med. 1974 Oct 10;291(15):755–758. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197410102911503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti P., Carrozzi L., Viegi G., Modena P., Ballerin L., Di Pede F., Grado L., Baldacci S., Pedreschi M., Vellutini M. Distribution of bronchial responsiveness in a general population: effect of sex, age, smoking, and level of pulmonary function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995 Jun;151(6):1770–1777. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.6.7767519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petermann W., Barth J., Entzian P. Heart failure and airway obstruction. Int J Cardiol. 1987 Nov;17(2):207–209. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(87)90132-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pison C., Malo J. L., Rouleau J. L., Chalaoui J., Ghezzo H., Malo J. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness to inhaled methacholine in subjects with chronic left heart failure at a time of exacerbation and after increasing diuretic therapy. Chest. 1989 Aug;96(2):230–235. doi: 10.1378/chest.96.2.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijcken B., Schouten J. P., Weiss S. T., Speizer F. E., van der Lende R. The relationship of nonspecific bronchial responsiveness to respiratory symptoms in a random population sample. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987 Jul;136(1):62–68. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/136.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sant'Ambrogio G., Remmers J. E., de Groot W. J., Callas G., Mortola J. P. Localization of rapidly adapting receptors in the trachea and main stem bronchus of the dog. Respir Physiol. 1978 Jun;33(3):359–366. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(78)90062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki F., Ishizaki T., Mifune J., Fujimura M., Nishioka S., Miyabo S. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness in patients with chronic congestive heart failure. Chest. 1990 Mar;97(3):534–538. doi: 10.1378/chest.97.3.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibert A. F., Allison R. C., Bryars C. H., Kirkpatrick M. B. Normal airway responsiveness to methacholine in cardiac asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989 Dec;140(6):1805–1806. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.6.1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WIDDICOMBE J. G. Receptors in the trachea and bronchi of the cat. J Physiol. 1954 Jan;123(1):71–104. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1954.sp005034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welty C., Weiss S. T., Tager I. B., Muñoz A., Becker C., Speizer F. E., Ingram R. H., Jr The relationship of airways responsiveness to cold air, cigarette smoking, and atopy to respiratory symptoms and pulmonary function in adults. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984 Aug;130(2):198–203. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.130.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolcock A. J., Peat J. K., Salome C. M., Yan K., Anderson S. D., Schoeffel R. E., McCowage G., Killalea T. Prevalence of bronchial hyperresponsiveness and asthma in a rural adult population. Thorax. 1987 May;42(5):361–368. doi: 10.1136/thx.42.5.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]