Abstract

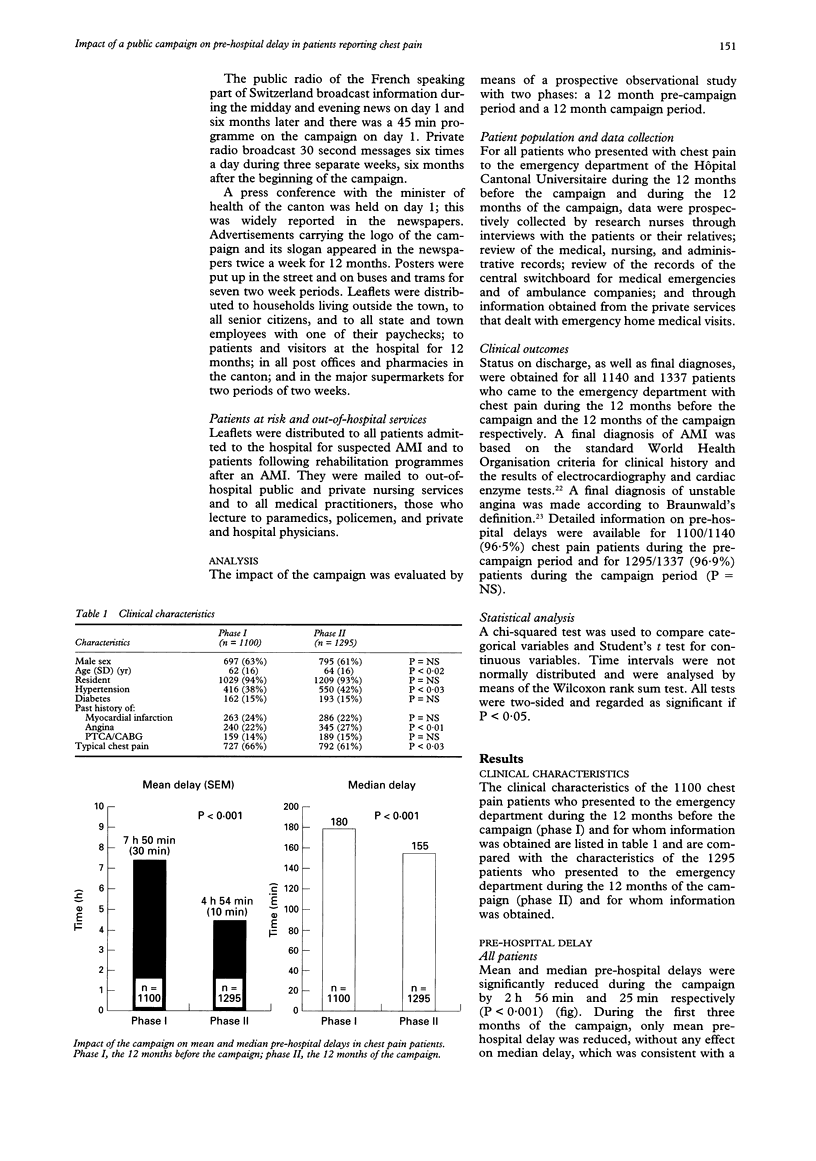

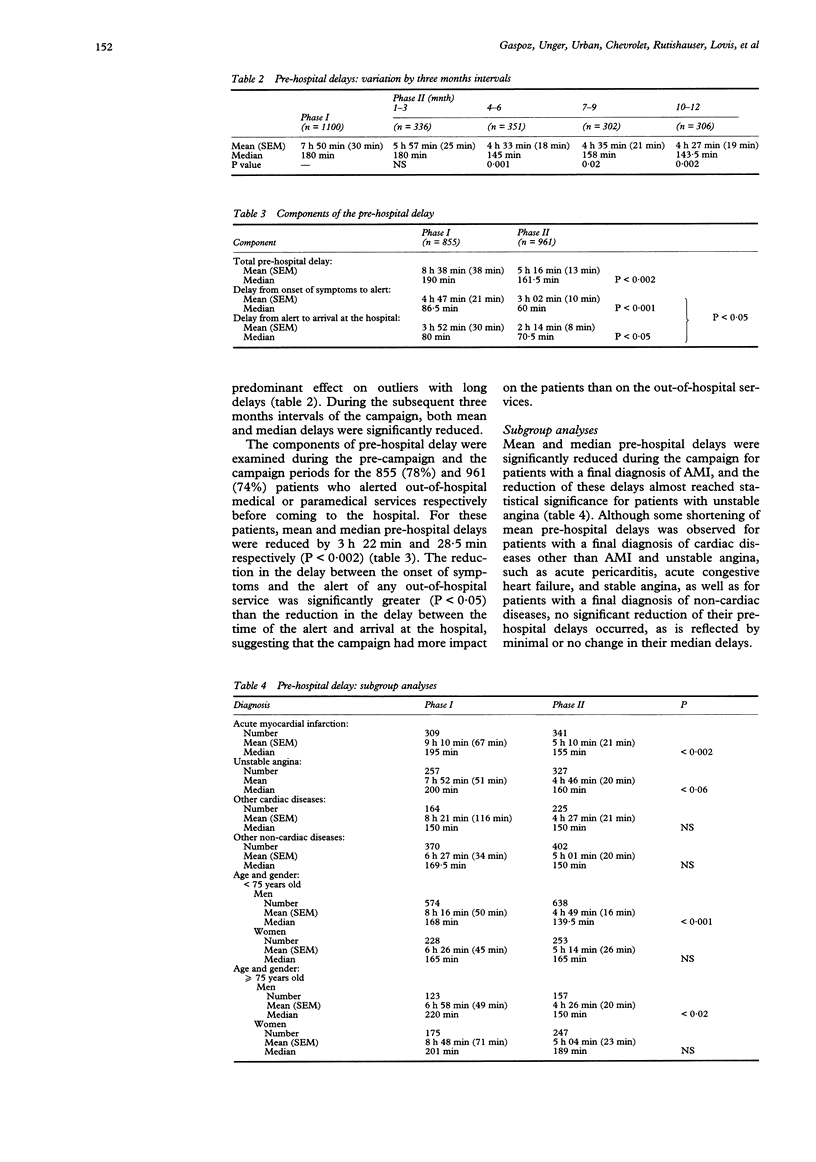

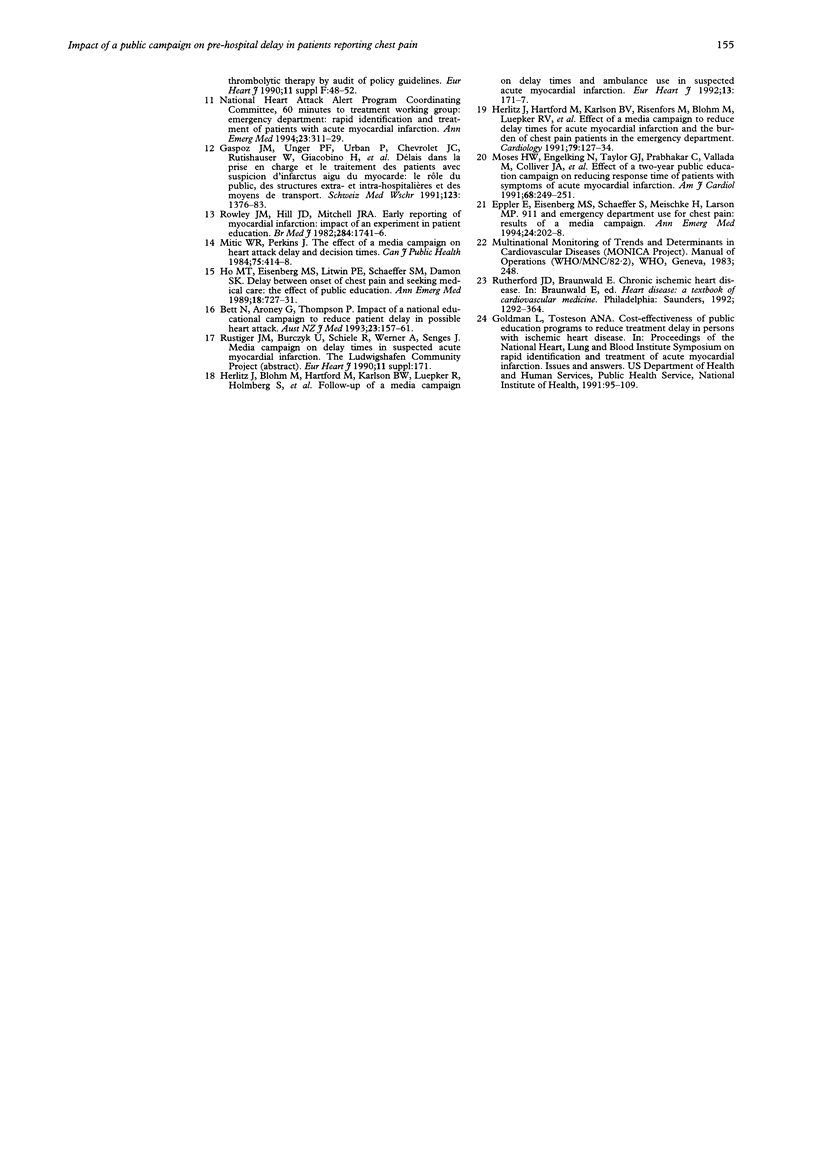

OBJECTIVE: To decrease pre-hospital delay in patients with chest pain. DESIGN: Population based, prospective observational study. SETTING: A province of Switzerland with 380000 inhabitants. SUBJECTS: All 1337 patients who presented with chest pain to the emergency department of the Hôpital Cantonal Universitaire of Geneva during the 12 months of a multimedia public campaign, and the 1140 patients who came with similar symptoms during the 12 months before the campaign started. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES: Pre-hospital time delay and number of patients admitted to the hospital for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and unstable angina. RESULTS: Mean pre-hospital delay decreased from 7h 50 min before the campaign to 4 h 54 min during it, and median delay from 180 min to 155 min (P < 0.001). For patients with a final diagnosis of AMI, mean delay decreased from 9 h 10 min to 5 h 10 min and median delay from 195 min to 155 min (P < 0.002). Emergency department visits per week for AMI and unstable angina increased from 11.2 before the campaign to 13.2 during it (P < 0.02), with an increase to 27 (P < 0.01) during the first week of the campaign; visits per week for non-cardiac chest pain increased from 7.6 to 8.1 (P = NS) during the campaign, with an increase to 17 (P < 0.05) during its first week. CONCLUSIONS: Public campaigns may significantly reduce pre-hospital delay in patients with chest pain. Despite transient increases in emergency department visits for non-cardiac chest pain, such campaigns may significantly increase hospital visits for AMI and unstable angina and thus be cost effective.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bett N., Aroney G., Thompson P. Impact of a national educational campaign to reduce patient delay in possible heart attack. Aust N Z J Med. 1993 Apr;23(2):157–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1993.tb01810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouten M. J., Simoons M. L., Hartman J. A., van Miltenburg A. J., van der Does E., Pool J. Prehospital thrombolysis with alteplase (rt-PA) in acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 1992 Jul;13(7):925–931. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppler E., Eisenberg M. S., Schaeffer S., Meischke H., Larson M. P. 911 and emergency department use for chest pain: results of a media campaign. Ann Emerg Med. 1994 Aug;24(2):202–208. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(94)70131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspoz J. M., Unger P. E., Urban P., Chevrolet J. C., Rutishauser W., Giacobino H., Héliot C., Khatchatrian N., Waldvogel F. A. Délais dans la prise en charge et le traitement des patients avec suspicion d'infarctus aigu du myocarde: le rôle du public, des structures extra- et intra-hospitalières et des moyens de transports. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1993 Jul 13;123(27-28):1376–1383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlitz J., Blohm M., Hartford M., Karlson B. W., Luepker R., Holmberg S., Risenfors M., Wennerblom B. Follow-up of a 1-year media campaign on delay times and ambulance use in suspected acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 1992 Feb;13(2):171–177. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlitz J., Hartford M., Karlson B. V., Risenfors M., Blohm M., Luepker R. V., Wennerblom B., Holmberg S. Effect of a media campaign to reduce delay times for acute myocardial infarction on the burden of chest pain patients in the emergency department. Cardiology. 1991;79(2):127–134. doi: 10.1159/000174870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho M. T., Eisenberg M. S., Litwin P. E., Schaeffer S. M., Damon S. K. Delay between onset of chest pain and seeking medical care: the effect of public education. Ann Emerg Med. 1989 Jul;18(7):727–731. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(89)80004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitic W. R., Perkins J. The effect of a media campaign on heart attack delay and decision times. Can J Public Health. 1984 Nov-Dec;75(6):414–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak C. Y., Eun H. M., McArthur R. G., Yoon J. W. Association of cytomegalovirus infection with autoimmune type 1 diabetes. Lancet. 1988 Jul 2;2(8601):1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92941-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley J. M., Hill J. D., Hampton J. R., Mitchell J. R. Early reporting of myocardial infarction: impact of an experiment in patient education. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982 Jun 12;284(6331):1741–1746. doi: 10.1136/bmj.284.6331.1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver W. D., Cerqueira M., Hallstrom A. P., Litwin P. E., Martin J. S., Kudenchuk P. J., Eisenberg M. Prehospital-initiated vs hospital-initiated thrombolytic therapy. The Myocardial Infarction Triage and Intervention Trial. JAMA. 1993 Sep 8;270(10):1211–1216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston C. F., Penny W. J., Julian D. G. Guidelines for the early management of patients with myocardial infarction. British Heart Foundation Working Group. BMJ. 1994 Mar 19;308(6931):767–771. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6931.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]