Highlights

-

•

Intestinal malrotation refers to the partial or complete failure of rotation of midgut around the superior mesenteric vessels in embryonic life which increases the risk of twisting midgut and subsequent obstruction and necrosis.

-

•

Malrotation in adults is a rare cause of midgut volvulus as though it should be considered in differential diagnosis in patients presented with acute abdomen and intestinal ischemia.

-

•

Typical radiological signs are corkscrew sign.

Keywords: Malrotation, Intestinal obstruction, Ladd’s procedure, Whirlpool sign

Abstract

Introduction

Intestinal malrotation refers to the partial or complete failure of rotation of midgut around the superior mesenteric vessels in embryonic life. Arrested midgut rotation results due to narrow-based mesentery and increases the risk of twisting midgut and subsequent obstruction and necrosis.

Presentation of case

40 years old female patient admitted to emergency service with acute abdomen and computerized tomography scan showed dilated large and small intestine segments with air-fluid levels and twisted mesentery around superior mesenteric artery and vein indicating “whirpool sign”.

Discussion

Malrotation in adults is a rare cause of midgut volvulus as though it should be considered in differential diagnosis in patients presented with acute abdomen and intestinal ischemia. Even though clinical symptoms are obscure, adult patients usually present with vomiting and recurrent abdominal pain due to chronic partial obstruction. Contrast enhanced radiograph has been shown to be the most accurate method. Typical radiological signs are corkscrew sign, which is caused by the dilatation of various duodenal segments at different levels and the relocation of duodenojejunal junction due to jejunum folding. As malrotation commonly causes intestinal obstruction, patients deserve an elective laparotomy.

Conclusion

Malrotation should be considered in differential diagnosis in patients presented with acute abdomen and intestinal ischemia. Surgical intervention should be prompt to limit morbidity and mortality.

1. Introduction

Intestinal malrotation refers to the partial or complete failure of 270 ° counterclockwise rotation of midgut around the superior mesenteric vessels in embryonic life [1]. Ligament of Treitz is not formed and distal duodenum and jejunum is aligned on the right side of columna vertebralis in these patients [2]. Arrested midgut rotation results due to narrow-based mesentery and increases the risk of twisting midgut and subsequent obstruction and necrosis. Most of the patients with malrotation present within first month of life and intestinal malrotation in adults is in the ratio of 0.2–0.5% [3]. The rate of incidence is approximately the same for men and women [4]. Adult malrotation usually presents with intermittent colicky pain and bile stained vomiting. Malrotation is the most frequent reason of midgut volvulus in adults and obstruction is observed mostly in colon [5]. In this article, we reviewed a case presented with cecal volvulus on grounds of malrotation.

2. Presentation of case

40 years old female patient admitted to emergency service with abdominal pain, vomiting and inability to pass flatus and stool for 24 h. Her medical history was unremarkable besides anxiety disorder. Blood pressure, pulse and fever were measured as 90/60 mmHg, pulse 120/min and 38 °C, respectively. Her physical examination revealed diffuse abdominal pain and muscular defense in each four quadrant as well as the abdominal distention. Rectal examination revealed formed stool without blood. Air-fluid level was present on abdominal radiograph (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Air-fluid level was present on abdominal radiograph.

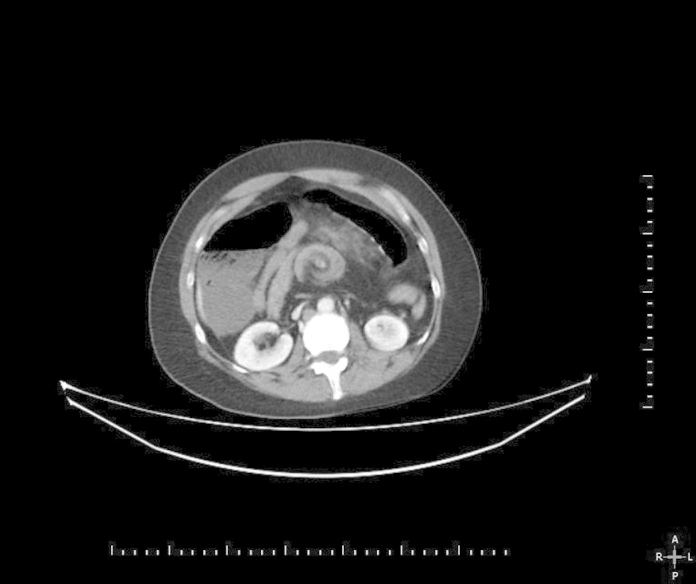

Computerized tomography scan showed dilated large and small intestine segments up to 67 mm diameter with air-fluid levels with twisted mesentery around superior mesenteric artery and vein indicating “whirpool sign” (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Computerized tomography scan shows dilated bowel loops and whirpool sign.

The patient immediately underwent emergency laparotomy. Exploration revealed twisted small bowels and ascending colon around mesentery (Fig. 3). Once bowel was untwisted, ascending colon and distal half of small bowel were found necrotic, most of the remaining small bowel was dusky and only 80 cm of proximal small bowel was looked healthy. Bowel were packed with warm pads for 10 min, some of the dusky segments were turned to pink. Ascending colon, ceacum and 100 cm of adjacent small bowels remained necrotic of which were resected and ileostomy were performed.

Fig. 3.

Exploration revealed twisted small bowels and ascending colon around mesentery.

Second-look laparotomy was performed after initial 24 h of the first laparotomy. It was discovered that 100 cm of small bowel from ileostomy was affected from a frank necrosis. Ischemic bowel segments were resected and only 80 cm of healthy looking small bowel was left. End-jejunostomy was reconstructed. Postoperatively the patient was put on parenteral hyperalimentation. After a stable period, the patient developed fever and abdominal sensitivity on the postoperative 12th day. Computerized tomography scan showed an abscess in the left lower abdominal quadrant. Abscess was drained percutaneously. Upon presence of intestinal content in drainage, patient developed intestinal fistula. At the postoperative 30rd day, patient developed fever, pancytopenia, hypotension, and anuria and did not respond to inotropic support. Patient died on postoperative day 33.

3. Discussion

Most of the malrotation cases are observed in the first month of life. Yet, it may be seen in adults [2]. Even though clinical symptoms are obscure, adult patients visit hospital mostly with complaints such as vomiting and recurrent abdominal pain, probably due to chronic partial obstruction [6], [7]. Some may present with malabsorption due to inability to eat and protein loss associated with diarrhea caused by chronic volvulus [1]. Imaging studies such as plain radiography, contrast enhanced stomach-duodenum radiography, ultrasonography and computerized tomography scan can help diagnose malrotation. Contrast enhanced radiograph has been shown to be the most accurate method [8]. Typical radiological signs are corkscrew sign, which is caused by the dilatation of various duodenal segments at different levels and the relocation of duodenojejunal junction due to jejunum folding [9]. In ultrasonography, the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) lies to the left or anterior to the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). Doppler USG may show the whirlpool sign with rotation of SMV around SMA which is typical for malrotation [10]. Besides, jejunal arteries lie to the right instead of to the left in computerized tomography scan as another diagnostic sign of malrotation [11]. Since malrotation commonly causes intestinal obstruction all patients deserve elective laparotomy [12]. Ladd’s procedure has been the standard procedure of elective treatment of intestinal malrotation since 1936 [13]. This procedure consists of following steps: first, midgut volvulus is untwisted; bands causing obstruction are divided; segments of colon and small bowel are set to neutral position and appendectomy is added to prevent future difficulty of diagnosis of appendicitis. Due to small and large bowel ischemia, Ladd’s procedure was not an option in our case and resection of ischemic segments was mandatory. In some patients, extensive small bowel resection may be required. However, short bowel syndrome and subsequent complications may be unavoidable in those patients. Other alternatives such as cecopexy, endoscopic untwisting and laparoscopic management have been used in previous cases in the literature. Laparoscopic Ladd’s procedure for elective cases has been shown to be effective, even superior to conventional procedure in some aspects [14]. Yet, it is clear that surgical options should be patient based.

The present case focuses attention at this critical rare subject by several points. First, presentation of adult malrotation cases can be obscure, even though whirlpool sign in abdomen computed tomography scan may give suspicion of bowel twisting. Yet, an acute presentation is commonly associates with extensive bowel necrosis and may lead to massive resection. We observed wide necrosis in small bowel and proximal large bowel during laparotomy. Thus, limited resection to save a segment of borderline ischemic bowel was performed, followed by a second look laparotomy after 24 h. Unfortunately, borderline ischemic bowel segment was not recovered and has to be removed in the second operation. End-jejunostomy has been performed instead of jejunocolostomy to avoid anastomotic leakage and further evaluate the viability of bowel-end. As the remaining length of small bowel was insufficient, the patient inevitably suffered from short bowel syndrome. Extensive labour was instituted to overcome high fluid-electrolyte loss and to deliver nutritional requirements. Management of patients with short bowel syndrome due to massive small bowel resection is a challenging situation and commonly complicating the patient’s status with electrolyte disturbances, malnutrition, immune deficiency, organ failure and sepsis. Refeeding enteroclysis is a helpful option in such patients, usually requires a considerable amount of healthy distal small bowel for absorption of nutrients, bile salts and fluids [15]. Our patients was left with a short segment of large bowel, therefore refeeding distally was thought to be not contributive to reabsorption of nutritional elements. Despite vigorous effort to maintain her fluid-electrolyte balance and to supply nutritional requirement via parenteral formulas, she developed intraabdominal abscess and subsequent enterocutaneus fistula, which both worsen her medical condition. Finally, she ended up with multiple organ failure due to uncontrolled sepsis. This case shows us timely recognition of malrotation is the key to save life if possible, but massive small bowel resection is sometimes unavoidable and may associate with fatal consequences.

4. Conclusion

Malrotation should be considered in differential diagnosis in patients presented with acute abdomen and intestinal ischemia. Patients may be asymptomatic or have obscure symptoms. Therefore, only anamnesis, physical examination and imaging may lead the surgeon to accurate diagnosis. Surgical intervention should be prompt to limit morbidity and mortality.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was not required and patient identifying knowledge was not presented in this report.

References

- 1.Sahu S.K., Raghuvanshi S., Sinha A., Sachan P.K. Adult intestinal malrotation presenting as midgut volvulus; case report. India Cer San D (J. Surg. Arts) 2012;1:18–21. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emanuwa O.F., Ayantunde A.A., Davies T.W. Midgut malrotation first presenting as acute bowel obstruction in adulthood: a case report and literature review. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2011;6(1):22. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-6-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palepu R.P., Harmon C.M., Goldberg S.P., Clements R.H. Intestinal malrotation discovered at the time of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2007;11(7):898–902. doi: 10.1007/s11605-006-0035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamal I.M. Defusing the intra-abdominal ticking bomb: intestinal malrotation in children. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2000;162(9):1315–1317. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernstein S.M., Russ P.D. Midgut volvulus: a rare cause of acute abdomen in an adult patient. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1998;171(3):639–641. doi: 10.2214/ajr.171.3.9725289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wanjari A.K., Deshmukh A.J., Tayde P.S., Lonkar Y. Midgut malrotation with chronic abdominal pain. North Am. J. Med. Sci. 2012;4(4):196. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.94950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ameh E.A., Nmadu P.T. Intestinal volvulus: aetiology, morbidity, and mortality in Nigerian children. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2000;16(1–2):50–52. doi: 10.1007/s003830050013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duran C., Ozturk E., Uraz S., Kocakusak A., Mutlu H., Killi, R Midgut volvulus: value of multidetector computed tomography in diagnosis. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2008;19(3):189–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gamblin T.C., Stephens R.E., Johnson R.K., Rothwell M. Adult malrotation: a case report and review of the literature. Curr. Surg. 2003;60(5):517–520. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7944(03)00030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orzech N., Navarro O.M., Langer J.C. Is ultrasonography a good screening test for intestinal malrotation? J. Pediatr. Surg. 2006;41(5):1005–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.12.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Applegate K.E., Anderson J.M., Klatte E.C. Intestinal malrotation in children: a Problem-solving approach to the upper gastrointestinal series 1. Radiographics. 2006;26(5):1485–1500. doi: 10.1148/rg.265055167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.P.K. Hota, D. Abhishek, V. Bhaskar, Adult midgut malrotation with ladd’s band: a rare case report with review of literatures M.M. Malek, R.S. Burd, The Optimal Management of Malrotation Diagnosed After Infancy: a Decision Analysis 1 The American journal of surgery 191 (2006) 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Malek M.M., Burd R.S. The optimal management of malrotation diagnosed after infancy: a decision analysis. Am. J. Surg. 2006;191(1):45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazziotti M.V., Strasberg S.M., Langer J.C. Intestinal rotation abnormalities without volvulus: the role of laparoscopy. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 1997;185(2):172–176. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(97)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coetzee E., Rahim Z., Boutall A., Goldberg P. Refeeding enteroclysis as an alternative to parenteral nutrition for enteric fistula. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16(10):823–830. doi: 10.1111/codi.12727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]