Abstract

We compared the eSwab system to a swab with an anaerobic transport semisolid agar system for their capacities to maintain the viability of 20 species of fastidious anaerobes inoculated on the bench and held at ambient or refrigerator temperature for 24 or 48 h. On average, both systems maintained similar viabilities among analogous groups of organisms at both temperatures, although there were quantitative differences among some species.

TEXT

Suitable specimen transport from collection to the laboratory is essential for accurate laboratory diagnostics. Given increasing laboratory centralization, transport times have increased as well, requiring systems to be robust enough to ensure sufficient organism collection, viability, and release. Specimens with anaerobic organisms have the added requirement of anaerobiosis for at least 48 h. The eSwab (Copan Diagnostics, Inc., Murrieta, CA) is a relatively new system compared to conventional gel-tube systems, and it lends itself to automation. The eSwab consists of a nylon-flocked swab, which provides better capillary action and stronger hydraulic uptake of liquids than do spun-fiber nylon or rayon swabs (1), and a screw-top tube containing liquid modified Amies medium. After specimen collection, the swab is inserted into the tube, and the scored shaft of the swab is easily broken to the length of the tube. A swab capture system in the cap locks the broken shaft into the lid of the tube after it is fully closed. Release studies that compared the flocked swab to conventional rayon or Dacron swabs have been performed (2), with favorable results, as have other studies that compared the viability of aerobic organisms and a small number of anaerobic organisms (1, 3–7). The recommended CLSI standard control strains have been shown in a previous study (1) to meet the requirements of the M40-A recommendations for transport systems (8). To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare numerous fastidious anaerobic bacteria. We compared the eSwab to Anaerobic Transport Medium (ATM; Anaerobe Systems, Morgan Hill, CA), both of which use a modified Amies medium in liquid or gel form, respectively, for the release and recovery of fastidious anaerobic bacteria from the swabs after 24 or 48 h at 4°C and room temperature (RT).

Materials and methods.

Twenty fastidious anaerobes, nine Gram-positive and 11 Gram-negative organisms, from various sources were selected for the study (Table 1). The organisms were identified by standard (9, 10) or molecular methods. This feasibility study of the recovery of various fastidious anaerobic bacteria was based on the CLSI document M40-A (8), which is the approved standard for quality control of transport media. A 24- to 48-h subculture of each organism was suspended in saline in the anaerobe chamber to a turbidity of a 0.5 McFarland standard (∼1.5 × 108 CFU/ml). To mimic clinical settings, the inoculation suspension was transferred to room air, and 0.1-ml aliquots were pipetted into microcentrifuge tubes to inoculate eSwabs and rayon swabs for the ATM system. Each system was set up for recovery testing at room temperature and 4°C; each temperature had separate tubes set up for subculture at t = 0, 24, and 48 h. At each sampling time, a suspension was made from each tube. The eSwab tube was vortexed for 5 s; the rayon swabs were removed from the ATM, and the tip was placed in 0.9 ml of saline and vortexed for 5 s. Each suspension was serially diluted, plated onto Brucella agar, and incubated in an anaerobic chamber for 24 to 72 h at 37°C, and colony counts were determined. The inoculum suspension was also serially diluted, and colony counts were performed. Although the CLSI M40-A quality-control standard recommends dilutions in triplicate and platings in duplicate, because this was a performance study of each transport system and not a quantitative quality-control analysis, each organism was studied once and each dilution was plated once. However, if the colony counts from the serial dilutions were inconsistent, the procedure was repeated. In addition, Clostridium difficile dilutions were also plated onto cycloserine-cefoxitin fructose agar with horse blood and taurocholate (HT) to better recover spores, which germinate more effectively in the presence of taurocholate (11).

TABLE 1.

Specimen sources of fastidious anaerobic bacteria tested

| Organism | Source |

|---|---|

| Gram negative | |

| Bacteroides fragilis | Appendix |

| Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron | Gluteal abscess |

| Bilophila wadsworthia | Appendix |

| Fusobacterium necrophorum | Tonsillar abscess |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum (1) | Facial lesion |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum (2) | Appendix |

| Porphyromonas asaccharolytica | Diabetic foot |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis | Tongue |

| Prevotella buccae | Abdominal abscess |

| Prevotella intermedia | Respiratory, sinus |

| Prevotella melaninogenica | Sputum |

| Gram positive | |

| Finegoldia magna | Respiratory, sinus |

| Parvimonas micra | Respiratory, sinus |

| Peptostreptococcus anaerobius | Unknown |

| Eggerthella lenta | Peri-rectal abscess |

| Propionibacterium acnes | Facial acne |

| Clostridium spp. | |

| Clostridium clostridioforme | Gluteal abscess |

| Clostridium difficile (1), nontoxigenic | Stool |

| Clostridium difficile (2), ribotype BI | Stool |

| Clostridium ramosum | Blood |

Release of sample from swabs.

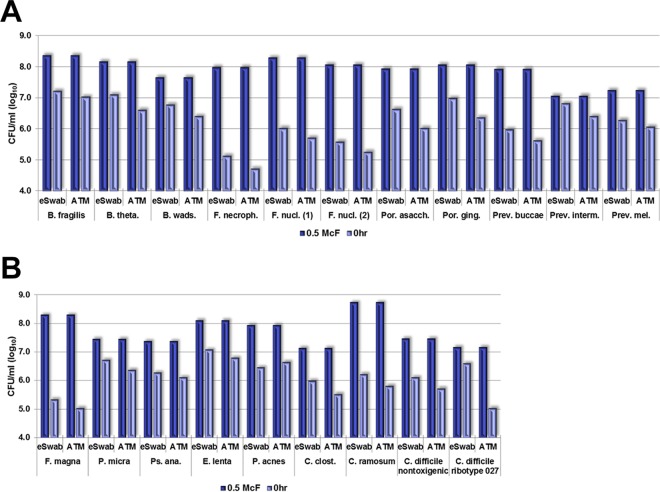

The eSwabs released more organisms than did the rayon swabs, although, on average, the difference was minor (Table 2). There were some exceptions (Fig. 1). In the Gram-negative group, the eSwabs and rayon swabs retained 1.5 and 1.9 log10 CFU/ml on average, respectively. All Fusobacterium spp. were retained ∼1 log10 CFU/ml more than the Gram-negative group average by both swab systems. In the Gram-positive group, the eSwabs and rayon swabs retained 1.5 and 1.6 log10 CFU/ml on average, respectively. Finegoldia magna was retained by both swab systems ∼1.5 log10 CFU/ml more than the Gram-positive group average. In the Clostridium spp. group, the eSwabs and rayon swabs retained 1.4 and 2.1 log10 CFU/ml on average, respectively. Clostridium ramosum was retained by 0.7 log10 CFU/ml more with the eSwab and 1.6 log10 CFU/ml more with the rayon swab compared to the Clostridium spp. group average.

TABLE 2.

Aggregate change

| Organism and time (h) | Aggregate change in: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eSwab [CFU/ml (log10)] |

ATM [CFU/ml (log10)] |

|||||

| Inoculuma | RTb | 4°C | Inoculum | RT | 4°C | |

| Gram negative (n = 11) | ||||||

| 0 | −1.5 | −1.9 | ||||

| 0–24 | −0.4 | −0.6 | −0.9 | −0.6 | ||

| 24–48 | −0.7 | −0.2 | −0.4 | −0.3 | ||

| Gram positive (n = 5) | ||||||

| 0 | −1.5 | −1.6 | ||||

| 0–24 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −0.8 | −0.5 | ||

| 24–48 | −0.1 | −0.3 | −0.2 | −0.3 | ||

| Clostridium spp. (n = 4) | ||||||

| 0 | −1.4 | −2.1 | ||||

| 0–24 | −1.2 | −1.2 | −1.0 | −1.2 | ||

| 24–48 | −0.3 | −0.4 | 0.2 | −0.1 | ||

Inoculum loss by organism retention of swab.

RT, ambient temperature.

FIG 1.

Release of inoculum by the eSwab and ATM systems. B. fragilis, Bacteroides fragilis; B. theta., Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron; B. wads., Bilophila wadsworthia; F. necroph., Fusobacterium necrophorum; F. nucl., Fusobacterium nucleatum; Por. asacch., Porphyromonas asaccharolytica; Por. ging., Porphyromonas gingivalis; Prev. buccae, Prevotella buccae; Prev. interm., Prevotella intermedia; Prev. mel., Prevotella melaninogenica; McF, McFarland standard.

Recovery of sample.

All organisms were recovered at room temperature (RT) and at 4°C at t = 0, 24, and 48 h (Fig. 2–4). Overall, both Gram-positive and Gram-negative organisms maintained similar average viabilities in both systems at RT and 4°C (Table 2); however, there were some exceptions.

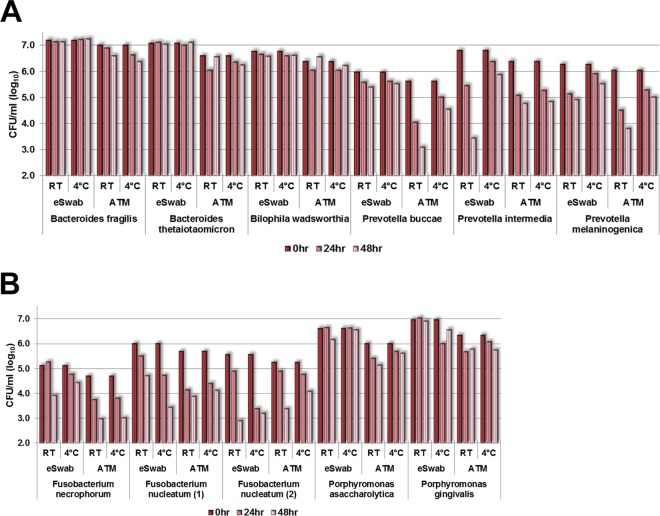

FIG 2.

Recovery of sample at t = 0, 24, and 48 h (log10 CFU/ml), Gram-negative group. P. micra, Parvimonas micra; Ps. ana., Peptostreptococcus anaerobius; E. lenta, Eggerthella lenta; P. acnes, Propionibacterium acnes; C. clost., Clostridium clostridioforme; C. ramosum, Clostridium ramosum.

In the Gram-negative group (Fig. 2), the best recoveries of all organisms over t0–24 h and t24–48 h at 4°C and RT were Bacteroides spp. and Bilophila wadsworthia, with an average loss of only 0.1 log10 CFU/ml over 48 h.

At 24 h, Fusobacterium necrophorum lost 0.9 log10 CFU/ml in ATM at 4°C and RT but had almost no loss in the eSwab. At 48 h, there was a 0.8 log10 CFU/ml loss in ATM at 4°C and RT, but, in the eSwab, there was a loss of 1.4 log10 CFU/ml at RT but only 0.3 log10 CFU/ml at 4°C. Best performance for F. necrophorum was the eSwab at 4°C. There were mixed results for the two Fusobacterium nucleatum species. One strain lost >1 log10 CFU/ml at 24 h in both systems and at both temperatures; the loss was less at 48 h for the eSwab at RT and for the ATM at 4°C and RT, but the eSwab lost >1 log10 CFU/ml at 4°C. The other F. nucleatum strain lost an average of 0.5 log10 CFU/ml in the eSwab at RT and ATM at 4°C and RT but lost 2.2 log10 CFU/ml in the eSwab at 4°C. Fusobacteria had the most loss in the Gram-negative group in both systems.

Porphyromonas asaccharolytica and Porphyromonas gingivalis had <1 log10 CFU/ml loss in both systems and at both temperatures over 48 h despite their fastidious nature.

On average, the Prevotella species lost the most during the first 24 h, 0.9 log10 CFU/ml for t0–24 h and 0.5 log10 CFU/ml for t24–48 h. After 48 h, Prevotella buccae decreased only 0.5 log10 on average at 4°C and RT in the eSwab but, in the ATM, lost 2.5 log10 CFU/ml at RT and 1.1 log10 CFU/ml at 4°C. Prevotella melaninogenica lost 2.2 and 1.0 log10 CFU/ml in the ATM at RT and 4°C; the eSwab loss was 1.3 and 0.7 log10 CFU/ml at RT and 4°C. Prevotella intermedia performed similarly to P. melaninogenica, except that the eSwab loss at RT was 3.3 log10 CFU/ml. The best performance for all Prevotella species was the eSwab at 4°C.

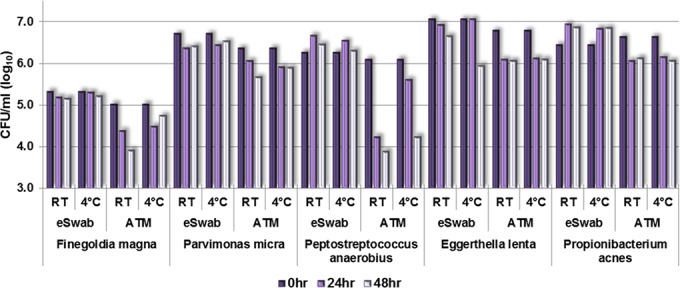

In the Gram-positive group (Fig. 3), the average loss was 0.3 and 0.2 log10 CFU/ml at t0–24 h and t24–48 h, respectively. The two systems performed similarly at RT and 4°C, with the exception of Peptostreptococcus anaerobius, which lost 2.2 and 1.9 log10 CFU/ml at RT and 4°C, respectively, over 48 h.

FIG 3.

Recovery of sample at t = 0, 24, and 48 h (log10 CFU/ml), Gram-positive group.

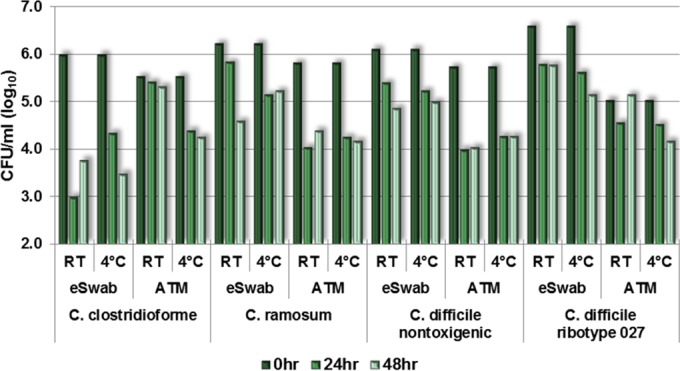

Clostridium spp. varied considerably (Fig. 4). Those strains known for producing more spores (e.g., C. difficile, ribotype 027) lost less in the first 24 h than in the second 24 h. The average loss of sample of Clostridium clostridioforme and C. ramosum was 1.1 log10 CFU/ml at t0–24 h, and there was no average loss at t24–48 h. The average loss of sample of C. difficile ribotype 027 was greater at t24–48 h than at t0–24 h. C. clostridioforme did not perform as well in the eSwab system at t0–24 h and t24–48 h.

FIG 4.

Recovery of sample at t = 0, 24, and 48 h (log10 CFU/ml), Clostridium group.

All counts were higher on HT than on Brucella agar, with the exception of the 027 ribotype of C. difficile, indicating more organism recovery from HT than from Brucella agar (results not shown).

The eSwab is an all-in-one collection device that was shown to provide equal or superior release, viability, and recovery performance for 48 h at room temperature and 4°C with the most fastidious anaerobic bacteria compared to the conventional anaerobic transport system consisting of a rayon swab and an anaerobic transport tube. In addition, the eSwab provides the added ability to be used in automated specimen-plating devices.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was funded by a research grant from Copan Diagnostics.

REFERENCES

- 1.Van Horn KG, Audette CD, Sebeck D, Tucker KA. 2008. Comparison of the Copan eSwab system with two Amies agar swab transport systems for maintenance of microorganism viability. J Clin Microbiol 46:1655–1658. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02047-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Horn KG, Audette CD, Tucker KA, Sebeck D. 2008. Comparison of 3 swab transport systems for direct release and recovery of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 62:471–473. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fontana C, Favaro M, Limongi D, Pivonkova J, Favalli C. 2009. Comparison of the eSwab collection and transportation system to an Amies gel transystem for Gram stain of clinical specimens. BMC Res Notes 2:244. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nys S, Vijgen S, Magerman K, Cartuyvels R. 2010. Comparison of Copan eSwab with the Copan Venturi Transystem for the quantitative survival of Escherichia coli, Streptococcus agalactiae and Candida albicans. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 29:453–456. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-0883-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silbert S, Kubasek C, Uy D, Widen R. 2014. Comparison of eSwab with traditional swabs for detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus using two different walk-away commercial real-time PCR methods. J Clin Microbiol 52:2641–2643. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00315-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smismans A, Verhaegen J, Schuermans A, Frans J. 2009. Evaluation of the Copan eSwab transport system for the detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a laboratory and clinical study. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 65:108–111. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stoner KA, Rabe LK, Austin MN, Meyn LA, Hillier SL. 2008. Quantitative survival of aerobic and anaerobic microorganisms in Port-A-Cul and Copan transport systems. J Clin Microbiol 46:2739–2744. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00161-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2003. Quality control of microbiological transport systems. Approved standard M40-A. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jousimies-Somer HR, Summanen P, Citron DM, Baron EJ, Wexler HM, Finegold SM. 2002. Wadsworth-KTL anaerobic bacteriology manual, 6th ed Star Publishing, Belmont, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Versalovic J, Carroll KC, Funke G, Jorgensen JH, Landry ML, Warnock DW. 2011. Manual of clinical microbiology, 10th ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tyrrell KL, Citron DM, Leoncio ES, Merriam CV, Goldstein EJ. 2013. Evaluation of cycloserine-cefoxitin fructose agar (CCFA), CCFA with horse blood and taurocholate, and cycloserine-cefoxitin mannitol broth with taurocholate and lysozyme for recovery of Clostridium difficile isolates from fecal samples. J Clin Microbiol 51:3094–3096. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00879-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]