Abstract

Background

Alcohol-induced blackouts, or memory loss for all or portions of events that occurred during a drinking episode, are reported by approximately 50% of drinkers and are associated with a wide range of negative consequences, including injury and death. As such, identifying the factors that contribute to and result from alcohol-induced blackouts is critical in developing effective prevention programs. Here, we provide an updated review (2010–2015) of clinical research focused on alcohol-induced blackouts, outline practical and clinical implications, and provide recommendations for future research.

Methods

A comprehensive, systematic literature review was conducted to examine all articles published between January 2010 through August 2015 that focused on examined vulnerabilities, consequences, and possible mechanisms for alcohol-induced blackouts.

Results

Twenty-six studies reported on alcohol-induced blackouts. Fifteen studies examined prevalence and/or predictors of alcohol-induced blackouts. Six publications described consequences of alcohol-induced blackouts, and five studies explored potential cognitive and neurobiological mechanisms underlying alcohol-induced blackouts.

Conclusions

Recent research on alcohol-induced blackouts suggests that individual differences, not just alcohol consumption, increase the likelihood of experiencing an alcohol-induced blackout, and the consequences of alcohol-induced blackouts extend beyond the consequences related to the drinking episode to include psychiatric symptoms and neurobiological abnormalities. Prospective studies and a standardized assessment of alcohol-induced blackouts are needed to fully characterize factors associated with alcohol-induced blackouts and to improve prevention strategies.

Keywords: Alcohol, Blackouts, Ethanol, Memory Impairments

Introduction

Alcohol use is a pervasive problem with well-known deleterious effects on memory. Alcohol-induced memory impairments vary in severity, ranging from mild deficits to alcohol-induced blackouts (Heffernan, 2008; White, 2003). Alcohol-induced blackouts are defined as amnesia, or memory loss, for all or part of a drinking episode. During a blackout, a person is able to actively engage and respond to their environment; however, the brain is not creating memories for the events. Alcohol-induced blackouts are often confused with passing out from alcohol, but blacking out and passing out are very different states of consciousness. A person experiencing a blackout is conscious and interacting with his or her environment; whereas, a person who has passed out from alcohol has lost consciousness and capacity to engage in voluntary behavior. Memory deficits during a blackout are primarily anterograde, meaning memory loss for events that occurred after alcohol consumption (White, 2003). It is important to note that short-term memory remains intact during an alcohol-induced blackout, and as such, an intoxicated person is able to engage in a variety of behaviors, including having detailed conversations and other more complex behaviors like driving a vehicle, but information about these behaviors is not transferred from short-term to long-term memory, which leads to memory deficits and memory loss for these events (White, 2003). There is no objective evidence that a person is in an alcohol-induced blackout (Pressman and Caudill, 2013), thus it can be difficult or impossible to know whether or not a drinker is experiencing a blackout (Goodwin, 1995). This is similar to the fact that one cannot know whether another person has a headache; the experience is happening inside that person’s brain, with no clear observable indices.

Based on the duration and extent of alcohol-induced memory loss, researchers have described two qualitatively distinct types of blackouts: en bloc and fragmentary (Goodwin et al., 1969a; Goodwin et al., 1969b). En bloc blackouts typically occur at higher blood alcohol concentrations (BAC), have a distinct onset, and involve complete memory loss for a specific period of the drinking event. Fragmentary blackouts (also known as “brown outs” or “gray outs”), however, involve partial amnesia during a drinking episode, but one may be able to recall events of the episode with relevant cues (Jennison and Johnson, 1994). Fragmentary blackouts occur more frequently than en bloc blackouts (Goodwin et al., 1969b; Hartzler and Fromme, 2003; White et al., 2004), but neither type appear to occur until breath alcohol concentrations (BrACs) are 0.06 g/dl or greater (Hartzler and Fromme, 2003). Estimates of BrACs indicated that most blackouts occurred around 0.20 g/dl, but as low as 0.14 g/dl (Ryback, 1970). According to a study of amnesia in people arrested for alcohol-related offenses (Perry et al., 2006), the probability of a fragmentary or an en bloc blackout was 50/50 at a BrAC of 0.22 g/dl and the probability of an en bloc blackout was 50/50 at a BrAC of 0.31 g/dl. As such, blackouts typically occur during binge or excessive drinking episodes. Further, gulping drinks and drinking on an empty stomach (Goodwin, 1995; Perry et al., 2006), which cause a rapid rise and high peak BAC, can also increase the likelihood of experiencing an alcohol-induced blackout.

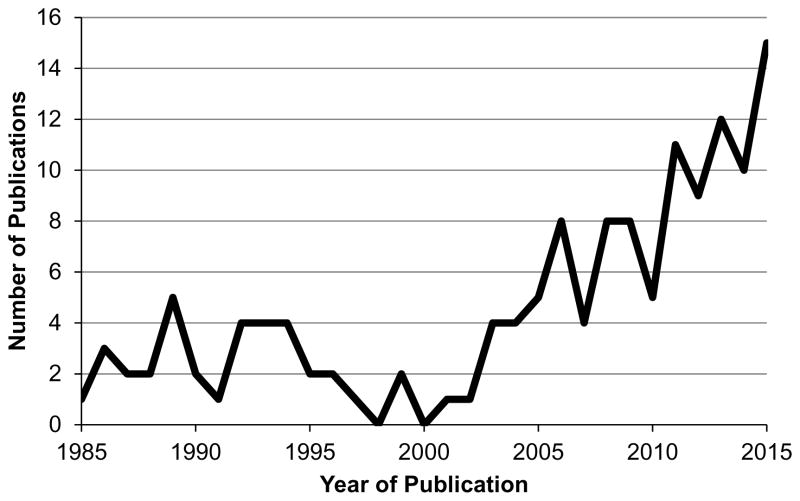

Although alcohol-induced blackouts were previously thought to occur only in individuals who were alcohol dependent (Jellinek, 1946), we now know that blackouts are quite common among healthy young adults. In fact, approximately 50% of college students who consume alcohol report having experienced an alcohol-induced blackout (Barnett et al., 2014; White et al., 2002). Consequently, there has been increased media and research interest in alcohol-induced blackouts over the past two decades with at least three reviews describing the phenomenon (Lee et al., 2009; Rose and Grant, 2010; White, 2003) a brief, descriptive section in a review on excessive alcohol use (White and Hingson, 2013) and a recently published memoir that poignantly describes the phenomenology of blackouts (Hepola, 2015) (Figure 1). Therefore, this systematic review provides an update (2010–2015) on the clinical research focused on alcohol-induced blackouts, outlines practical and clinical implications, and provides recommendations for future research.

Figure 1.

Number of published journal articles or reviews that evaluate alcohol-induced blackouts per year (1985 to 2015). The graph represents published articles and reviews published in English and includes both animal and human studies with the terms “blackout” and “alcohol” in the title, abstract, and/or keyword.

Materials and Methods

A Medline search was conducted in September 2015 to identify publications that included either “alcohol” or “ethanol” as one search term and at least one blackout-related search term (e.g., “blackouts”, “blacked out”). The wildcard character “*” was used to include all forms of the root word. The most recent review of blackouts was published in 2010 (Rose and Grant, 2010) and there has since been extensive new research; therefore we limited our review to articles published between January 2010 and August 2015. After removing duplicates, case studies, articles that were not published in English, and studies not conducted in humans, the remaining publications were reviewed to determine whether they met inclusion criteria, namely that the study examined vulnerabilities, consequences, and possible mechanisms for alcohol-induced blackouts.

Results

Study Characteristics

A total of 26 publications met the criteria to be included in the review (see Table 1 for study details). Fifteen studies examined prevalence and/or predictors of alcohol-induced blackouts. Six publications described consequences of alcohol-induced blackouts, and five studies explored potential cognitive and neurobiological mechanisms underlying alcohol-induced blackouts.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Published Studies Examining Alcohol-Induced Blackouts between 2010 and 2015

| Study reference | Design | Sample | Methods

|

Blackout-related findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies on prevalence and predictors of alcohol-induced blackouts | ||||

| Barnett and colleagues (2014) | Multisite, multicohort, prospective | 1,053 first-year college students, Ages: 16–21 (M=18.4), 58% female |

|

Blackouts and getting physically sick were

most common negative consequences 54.2% of subjects endorsed a blackouts during first year of college Almost 1 in 5 drinking weeks resulted in a blackout |

| Boekeloo and colleagues (2011) | Cross-sectional | 307 incoming freshman college students, 59% female |

|

Freshman who Drink to Get Drunk (DTGD) were

more likely to have consumed alcohol prior to going out, participated in

a drinking game, drank heavily on a non-school night, used liquor/beer,

combined alcohol and drugs, experienced a hangover, vomited, passed out,

and/or blacked out 50% of those who DTGD endorsed a blackout during past 30 days |

| Brister and colleagues (2011) | Cross-sectional | 150 21-year-olds, 50% female |

|

40% reported experiencing a blackout

during their 21st birthday celebration Physical (e.g., blackout and hangover) and behavioral risks were predicted by higher estimated BACs |

| Chartier and colleagues (2011) | Prospective | 166 subjects from the community who consume alcohol, Ages: 23–29 (M=25.9), 60% female |

|

Drinking in hazardous situations, blackouts,

and tolerance were most common alcohol problem Blackouts were more prevalent in whites and males Age of onset for blackouts occurred at ~19 years of age |

| Clinkinbeard and Johnson (2013) | Cross-sectional | 272 college students, Ages: 18–25 (M=19.9), 52% male |

|

Binge drinkers were more likely to define binge drinking in an extreme manner such that the drinking results in vomiting or blacking out |

| Hallett and colleagues (2013) | Cross-sectional | 942 Australian university students participating in an Internet-based intervention trial and scored ≥8 on AUDIT, Ages: 17–24 (M=19.4), 53% male |

|

Blackouts were one of the most frequently

reported non-academic problem (44.8%) Several negative consequences, including blackouts, were rated as positive by a large proportion of the sample |

| LaBrie and colleagues (2011) | Multisite, cross-sectional | 2,546 college students, 59% female |

|

25% of students reported blacking out

during at least one occasion in which prepartying occurred in the past

30 days Greek affiliation, family history of alcohol abuse, frequency of prepartying, and both playing drinking games and consuming shots of liquor while prepartying increased the likelihood of blacking out |

| Marino and Fromme (2015) | Prospective | 1,154 young adults, Mean age 23.8 years, 65% female |

|

66% of sample reported experiencing an

alcohol-induced blackout Women were more likely to report blackouts than men Compared with women with a maternal family history of problematic alcohol use, men with a maternal family history of problematic alcohol use were more than twice as likely to report blackouts |

| Merrill and Read (2010) | Cross-sectional | 192 regularly drinking college students, Ages: 18–24 (M=19.1), 52% male |

|

SEM analyses revealed a direct association between enhancement motives and blackouts |

| Merrill and colleagues (2014) | Prospective | 552 college students, Ages: 18–24, 57% age 21, 62% female |

|

SEM analyses revealed an indirect association between enhancement motives at Time 1 and blackouts at Time 2 through increased levels of alcohol use at Time 2 |

| Ray and colleagues (2014) | Prospective | 336 first-year student drinkers, Ages: 18–20 (M=18.2), 53% male |

|

Students who reported higher levels of alcohol

quantity across events were more likely to report experiencing

blackout Controlling for individual differences in typical drinking, those who played drinking games more frequently were more likely to experience a blackout When women, compared to men, consumed 1 more drink than their usual amount, odds of experiencing a blackout increased by 13% |

| Sanchez and colleagues (2015) | Field study | 1,222 nightclub patrons in Sao Paulo, Brazil, Ages: 51% ≤ 24, 57% male |

|

Blackouts were more prevalent in those who engaged in binge drinking while at the nightclub |

| Schuckit and colleagues (2015) | Prospective | 1,402 drinking adolescents, Ages: 15–19 (M=15.5), 60% female |

|

In the 2 years prior to age 15, almost

30% of youth reported experiencing an alcohol-induced

blackout At age 19, 74% of youth reported experiencing an alcohol-induced blackout Four latent trajectory classes were identified:

|

| Wahl and colleagues (2013) | Multisite, cross-sectional | 757 9th and 10th grade students in Germany Ages: 15–16 (M=15.6) 50% female |

|

Predrinking is associated with experiencing alcohol-induced blackouts |

| Wilhite and Fromme (2015) | Prospective | 829 college students Mean age of 21.8 years 66% female |

|

Alcohol dependence symptoms in Year 4

predicted increased frequency of blackouts and social/emotional

consequences during the following year Blackouts during Year 4 predicted increased alcohol-related social and emotional consequences, but not alcohol dependence symptoms in Year 5 |

| Studies on consequences of alcohol-induced blackouts | ||||

| Bae and colleagues (2015) | Cross-sectional | 42,347 subjects, 54% female |

|

Blackouts were associated with suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts in males, and suicidal ideation in females |

| Mundt and Zakletskaia (2012) | Multisite, prospective | 954 undergraduate and graduate students, Ages: 18–41, 44% between the ages 18–20, 51% female |

|

At baseline, 52% of males and

50% of females had experienced an alcohol-induced blackout in

the past year One in eight emergency department visits over a two-year period were associated with blackouts Estimates indicated that blackout-associated emergency department visit costs ranged from $469,000–$546,000/year |

| Mundt and colleagues (2012) | Multisite, prospective | 954 undergraduate and graduate students, Ages: 18–41, 44% ages 18–20, 51% female |

|

Approximately 7% of the sample

reported experiencing 6 or more blackouts in the past

year Alcohol-induced blackouts at baseline exhibited a dose-response on odds of alcohol-related injury during follow-up increasing from 1.57 among those who reported 1–2 blackouts to 2.64 for those reporting six or more blackouts |

| Neupane and Bramness (2013) | Multisite, cross-sectional | 188 AUD patients in residential alcohol treatment, Ages: 14–64, median=35, 89% male |

|

History of alcohol-induced blackouts was predictive of comorbid MD diagnosis |

| Read and colleagues (2013) | Prospective | 997 incoming first year college students, Ages: 18–24 (M=18.1), 65% female |

|

Blackout experience during the first year

predicted later increases in drinking among males Blackout experience during the first year predicted decreased drinking the following year among females |

| Winward and colleagues (2014) | Prospective | 23 heavy episodic drinking youth and 23 demographically-matched non-drinking youth, Ages: 16–18 (M=17.7), 50% female |

|

Heavy episodic drinking youth responded with

greater emotional response to the PASAT-C, but emotional responses

decreased with sustained abstinence Among heavy episodic drinking youth, greater lifetime and recent alcohol consumption, alcohol-induced blackouts, and withdrawal symptoms were associated with increased negative affect with PASAT-C exposure |

| Studies on potential cognitive and neurobiological mechanisms | ||||

| Chitty and colleagues (2014) | Cross-sectional | 64 patients with bipolar disorder and 49 controls, Ages: 18–30 (M=23), 66% female |

|

In both patients and controls, reduced hippocampal-GSH was associated with blackout presence/severity |

| Silveri and colleagues (2014) | Cross-sectional | 48 young adults were included in analyses (21 binge drinkers and 27 light drinkers) Ages: 18–24 ~50% female |

|

Overall, binge drinkers had lower gamma

amino-butyric acid and N-acetyl-aspartate in the anterior cingulate

cortex than light drinkers When stratified by blackout history, binge drinkers with a history of blackouts had lower anterior cingulate cortex glutamate than light drinkers |

| Wetherill and colleagues (2013) | Multicohort, prospective | 60 substance-naïve youth who later transition into heavy drinking and experienced a blackout (n=20) or not (n=20) or youth who remain abstinent (n=20) Ages: 12–14 at baseline 55% male |

|

Prior to initiating substance use, youth who

later transitioned into heavy drinking and experienced blackouts showed

greater activation during inhibitory processing than nondrinkers and

youth who transitioned into heavy drinking but did not experience

blackouts Mean activation during correct inhibitory processing in the left and right middle frontal brain regions at baseline predicted future blackout experience, after controlling for follow-up externalizing behaviors and lifetime alcohol consumption |

| Wetherill and Fromme (2011) | Cross-sectional | 88 college students who consume alcohol (44 with a history of fragmentary blackouts; 44 without a history of blackouts) Ages: 21–22 (M=21.6) 50% female |

|

Individuals with and without a history of

blackouts showed similar memory performance when

sober Individuals who consumed alcohol and had a positive history of fragmentary blackouts showed greater contextual memory impairments than those who had not previously experienced a blackout |

| Wetherill and colleagues (2012) | Cross-sectional | 24 college students who consume alcohol (12 with a history of fragmentary blackouts and 12 without a history of fragmentary blackouts) Ages: 21–23 (M=21.3) 50% female |

|

Groups did not show significant differences

when sober Individuals with a history of fragmentary blackouts showed attenuated neural responses to contextual memory recollection in the right posterior parietal cortex and bilateral dorsolateral PFC |

AEQ-A, Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire – Adolescent; BPRS, APS, Alcohol Problems Scale; AREAS, Academic Role Expectations and Alcohol Scale; AUD, alcohol use disorder; AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; BIS-11, Barratt Impulsiveness Scale; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; BrAC, breathe alcohol concentration; BSSS, Brief Sensation-Seeking Scale; CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist; CDDR, Customary Drinking and Drug Use Record; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; DASS, Depression Anxiety Stress Scale; DDQ, Daily Drinking Questionnaire; ESYTC, Edinburgh Study of Youth Transitions and Crime; FHAM, Family History Assessment Module; FTQ, Family Tree Questionnaire; GNG, go-nogo; GSH, glutathione; HDRS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; 1H-MRS, Proton magnetic resonance imaging spectroscopy; HSS, Health Screening Survey; IPAS, Important People and Activities Scale; IPIP-NEO, International Personality Inventory Pool form of the NEO 5-factor Personality Inventory; MD, major depression, MEPS, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PANAS, Positive and Negative Affect Scale; PASAT-C, Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test-Computerized Version; PDS, Pubertal Development Scale; POMS, Profile of Mood States; RAPI, Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders; SDQ, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; SEM, Structural equation modeling; SRE, Self-ratings of the effects of alcohol; SSAGA-I, Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism-I; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; TLFB, Timeline Followback; TMT, Trail Making Test, WAIS-III, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – 3rd edition; WASI, Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence; WHO-ASSIST, World Health Organization’s Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test; WMS-III, Wechsler Memory Scale – 3rd edition; WRAT, Wide Range Achievement Test; YAACQ, Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire; YAAPST, Youth Adult Alcohol Problems Screening Test; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale; YSR/ASR, Youth Self-Report/Adult Self-Report.

Prevalence and Predictors of Alcohol-Induced Blackouts

The majority of the publications identified for this review examined binge drinking and alcohol-related consequences, including blackouts, among young adults and college students and reported prevalence rates ranging from approximately 20–55% (Barnett et al., 2014; Boekeloo et al., 2011; Brister et al., 2011; Chartier et al., 2011; Clinkinbeard and Johnson, 2013; Hallett et al., 2013; Sanchez et al., 2015; Wilhite and Fromme, 2015). Although prevalence rates were typically around 50%, one study reported a prevalence rate of only about 20%; however, this was a qualitative study examining how university students define binge drinking (Clinkinbeard and Johnson, 2013). As such, participants were not directly asked whether they had experienced an alcohol-induced blackout, but rather participants were asked to describe binge drinking and then researchers categorized whether the responses described alcohol-induced blackouts. In addition to their prevalence rate of 54%, Barnett and colleagues (2014) found that college students reported experiencing an alcohol-induced blackout nearly once every five drinking weeks during the first year of college. Thus, alcohol-induced blackouts are not only common among those who consume alcohol, but also recur over time.

Using longitudinal methods, Schuckit and colleagues (2015) and Wilhite and Fromme (2015) focused specifically on prospective analyses of alcohol-induced blackouts. Schuckit and colleagues (2015) used latent class growth analysis to evaluate the pattern of occurrence of alcohol-induced blackouts across 4 time points in 1,402 drinking adolescents between the ages of 15–19. Surprisingly, 30% of the adolescents reported experiencing an alcohol-induced blackout at the age of 15, which increased to 74% at age 19. Analyses revealed 4 classes in the patterns of the occurrence for blackouts (i.e., no blackouts, blackouts rapidly increasing with age, blackouts slowly increasing, and blackouts consistently reported), with female sex, higher drinking quantities, smoking, externalizing characteristics, and estimated peer substance use predicting class membership (Schuckit et al., 2015). In general, these findings are consistent with previous research (Rose and Grant, 2010; White et al., 2002) and indicate that alcohol-induced blackouts are common even among early adolescents, which is particularly concerning given that the adolescent brain is undergoing significant developmental changes.

Wilhite and Fromme (2015) examined the associations between alcohol-induced blackouts, alcohol dependence symptoms ((as measured by the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (White and Labouvie, 1989)), and social and emotional negative consequences across 2 years among 829 young adults who were transitioning out of college. They found that alcohol dependence symptoms predicted an increased frequency of blackouts and consequences the following year. Alcohol-induced blackouts during the past three months prospectively predicted increased social and emotional negative consequences, but not alcohol dependence symptoms the following year. These findings contradict Jellinek’s theory of alcoholism, which posits that alcohol-induced blackouts are a precursor of alcoholism (Jellinek, 1952).

Potential genetic influences

Behavioral genetic research suggests that there is a heritable component to experiencing alcohol-induced blackouts (Luczak et al., 2006; Nelson et al., 2004; Slutske et al., 1999). Two recent studies explored genetic influences by examining the potential effects of family history of alcohol problems on blackout occurrence (LaBrie et al., 2011; Marino and Fromme, 2015). In a study of 2,546 college students, LaBrie and colleagues (2011) found that a family history of alcohol problems increased the likelihood of blacking out. Using data from a longitudinal study of college students, Marino and Fromme (2015) explored whether maternal or paternal family history of problematic alcohol use were better predictors than a general measure of overall family history on the likelihood of experiencing an alcohol-induced blackout. They further tested whether gender moderated the association in a sample of 1,164 college students. Although prenatal alcohol exposure was not assessed and could influence findings, the researchers found that compared to women with a maternal history of problematic alcohol use, men with a maternal history of problematic alcohol use were more than twice as likely to report experiencing an alcohol-induced blackout.

Based on the Marino and Fromme (2015) findings, one could speculate that a genetic vulnerability to alcohol-induced blackouts is expressed only under certain environmental conditions, representing a possible gene by environment interaction. For example, a mother with problematic drinking habits might contribute to an environment that is characterized by lower parental monitoring and increased alcohol availability. These environmental factors, in turn, could create stress and contribute to early initiation of alcohol use and maladaptive drinking behaviors in her offspring, especially sons, who are genetically predisposed to alcohol misuse and alcohol-induced blackouts. Given the potential impact of these findings on prevention and intervention programs, additional research examining genetic and environmental factors contributing to alcohol-induced blackouts is needed.

Prepartying and drinking games

Three studies examined high-risk drinking behaviors common among young adults known as “prepartying,” “pregaming,” and “drinking games” (LaBrie et al., 2011; Ray et al., 2014; Wahl et al., 2013). Typically, these drinking behaviors involve fast-paced drinking over a short period of time and can cause a rapid rise and high peak BAC, which increases the likelihood of experiencing an alcohol-induced blackout (Goodwin, 1995; Perry et al., 2006). LaBrie and colleagues (2011) examined risk factors for blackouts among 2,546 college students who reported past month prepartying. Of these students, 25% reported blacking out during at least one occasion over the past month when prepartying had occurred. Similarly, Wahl and colleagues (2013) examined predrinking and associated behaviors among 757 German high school students and found that those who reported engaging in predrinking were more likely to experience alcohol-induced blackouts. Using an event-level approach, Ray and colleagues (2014) found that students consumed more alcohol during drinking game events compared to non-drinking game events, and all students were more likely to experience an alcohol-induced blackout during events when drinking games occurred. This provides additional support for the importance of drinking style (e.g., pace and type of alcohol), as well as amount of alcohol consumed, in the occurrence of alcohol-induced blackouts.

Drinking motives

Because drinking motives are predictors of alcohol use and consequences, recent research has also examined the association between drinking motives and alcohol-induced blackouts (Boekeloo et al., 2011; Merrill and Read, 2010; Merrill et al., 2014). Merrill and Read (2010) examined whether affect-relevant motivations for alcohol use (i.e., coping: drinking to alleviate negative affect; enhancement: drinking to increase positive affect) were associated with specific types of consequences, including alcohol-induced blackouts, in 192 regularly drinking college students. Using structural equation modeling (SEM), the authors reported a direct path between enhancement motives and blackouts, suggesting that individuals who drink to increase positive affect might consume alcohol in a manner that results in a rapid increase in BAC and alcohol-induced blackouts, such as taking shots of liquor or drinking rapidly. Merrill and colleagues (2014) conducted a follow-up, longitudinal study examining whether coping and enhancement motives predicted alcohol consequences, including alcohol-induced blackouts, over the course of one year in 552 college students and reported that enhancement motives indirectly predicted blackouts the following year. Although enhancement motives did not directly predict alcohol-induced blackouts in the longitudinal study, drinking to increase positive affect seems to involve a style of drinking that increases the likelihood of blackouts.

Boekeloo and colleauges (2011) examined a different type of drinking motive -“drinking to get drunk,” which the authors defined as “pre-meditated, controlled, and intentional consumption of alcohol to reach a state of inebriation” (p. 89). They explored the prevalence and correlates of this type of drinking behavior in 307 incoming freshman who reported consuming alcohol over the past 30 days. Nearly 77% of the incoming freshmen reported drinking alcohol in a pre-meditated, intentional manner with the goal of becoming intoxicated. Compared to those who did not drink to get drunk, individuals who reported drinking to get drunk were more likely to experience an alcohol-induced blackout. Further, consistent with the prepartying and drinking games studies described previously (LaBrie et al., 2011; Ray et al., 2014; Wahl et al., 2013), individuals who reported drinking to get drunk were also more likely to have prepartied and participated in drinking games.

Consequences of Alcohol-Induced Blackouts

As indicated by the research described above, alcohol-induced blackouts typically occur following a rapid rise and high peak level of alcohol intoxication, and as such, alcohol-induced blackouts are associated with and predictive of other consequences and behaviors. Using SEM, Read and colleagues (2013) examined whether alcohol-related consequences, including alcohol-induced blackouts, predicted college students’ alcohol consumption one year later and whether these associations differed between men and women. Findings revealed that alcohol-induced blackouts during the first year of college predicted alcohol use the following year, with blackouts predicting later drinking increases in men and decreases in women (Read et al., 2013). Further, using data from a randomized controlled trial of screening and brief physician intervention for problem alcohol use among 954 undergraduate and graduate students, Mundt and colleagues (2012) examined whether baseline alcohol-induced blackouts prospectively identified individuals with alcohol-related injury over the subsequent 2 years after controlling for heavy drinking days (Mundt and Zakletskaia, 2012; Mundt et al., 2012). Findings indicated that alcohol-induced blackouts at baseline predicted alcohol-related injury over time with individuals who reported experiencing 1–2 blackouts at baseline being 1.5 times more likely to experience an alcohol-related injury, and those who reported 6 or more blackouts being over 2.5 times more likely to experience an alcohol-related injury. Mundt and Zakletskaia (2012) conducted a follow-up analysis on the same sample and found that one in eight emergency department visits for alcohol-related injuries involved an alcohol-induced blackout. Thus, among young adults, experiencing a blackout increases the likelihood of having an alcohol-related injury over time, even after controlling for heavy drinking.

Recent research has also investigated the associations between alcohol-induced blackouts and psychiatric symptomatology (Bae et al., 2015; Neupane and Bramness, 2013; Winward et al., 2014). Using data provided by the Korea National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey from 2007–2011, Bae and colleagues (2015) examined associations between alcohol consumption and suicidal behavior in 42,347 Korean subjects and reported that alcohol-induced blackouts were associated with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in males and suicidal ideation in females. Further, in a sample of 188 Nepalese patients in treatment for alcohol use disorder, a history of alcohol-induced blackouts was predictive of having comorbid major depression (Neupane and Bramness, 2013).

Winward and colleagues (2014) used the Paced Auditory Serial Attention Test (PASAT-C) Computer Version to examine affective reactivity, cognitive performance, and distress tolerance in relation to blackouts, during early abstinence among 23 heavy episodic drinking adolescents (ages 16–18) compared to 23 matched, non-drinking controls. Findings revealed that heavy episodic drinking adolescents responded with greater emotional response to the PASAT-C compared to controls, and among heavy episodic drinking adolescents, greater frequency of alcohol-induced blackouts during the past three months was correlated with greater increases in frustration and irritability during the PASAT-C. Overall, these findings suggest that alcohol-induced blackouts can have profound effects on an individual’s overall health and well-being, above and beyond the effects of heavy alcohol consumption.

Potential Neurobiological Mechanisms of Alcohol-Induced Blackouts

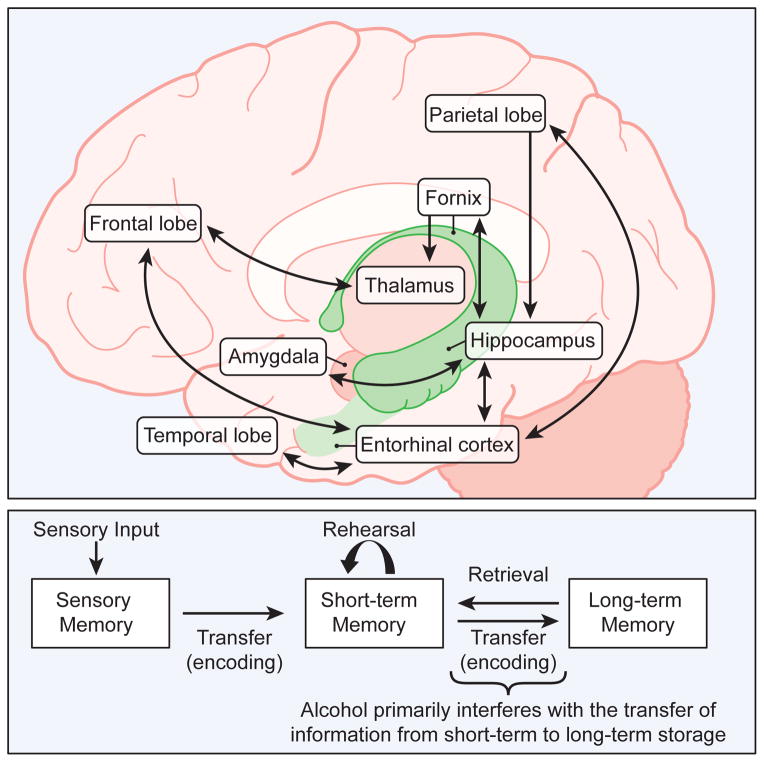

Although early theories posited that alcohol’s effects on cognition and behavior were due to alcohol’s general disruption of brain function and depression of the central nervous system, preclinical and clinical research now indicates that alcohol-induced cognitive and memory deficits are caused by alcohol’s effects on the hippocampus and related neural structures (Figure 2) (White et al., 2000). Briefly, the hippocampus is a brain structure involved in memory formation for events and has been found to be particularly sensitive to alcohol. Indeed, animal research published prior to the period of the current review revealed that blackouts are caused by alcohol disrupting the transfer of information from short-term to long-term memory by interfering with hippocampal, medial septal, and frontal lobe functioning (White, 2003; White et al., 2000). Although the mechanism of alcohol-induced blackouts is now known, our understanding of the specific neurobiological vulnerability and why some individuals are more likely to experience alcohol-induced blackouts while others are not has been an area of growing interest.

Figure 2.

General overview of alcohol’s effects on memory and alcohol-induced blackouts. Top panel: Sagittal representation of the human brain and the primary structures and associations involved in episodic memory. Bottom panel: A general model of memory formation, storage, and retrieval reproduced with permission from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism publication (White, 2003). Alcohol interferes with all stages of the memory process, but the alcohol’s primary effect appears to be on the transfer of information from short-term to long-term storage. Intoxicated individuals are typically able to recall information immediately after it is presented and can keep the information active in short-term memory for one minute or more if they are not distracted. Individuals may also be able to recall long-term memories formed before they became intoxicated; however, after just one or two drinks, individuals show memory impairments. Alcohol can interfere with these memory processes so severely that once sober, the individual is not able to recall all or portions of the events that occurred during the drinking episode.

Contextual memory (often described more broadly as source memory) refers to memory for details associated with a specific event (e.g., where a person was for the event, who was at the event). These memory details facilitate recall by enabling a person to consciously re-experience past events (Tulving, 2002). As such, Wetherill and Fromme (2011) examined the effects of acute alcohol consumption on contextual memory and recall among individuals with and without a history of fragmentary blackouts in an attempt to better understand why some individuals experience alcohol-induced memory impairments whereas other do not, even when these individuals have similar drinking histories and are at comparable BrACs (Wetherill and Fromme, 2011). Using longitudinal data to identify 88 young adults (mean age: 21.6 years ± 0.5; alcohol consumed 3 times a week, 3 standard drinks per occasion over the past 3 months) with (n=44) and without (n=44) a history of alcohol-induced blackouts who reported comparable drinking histories, denied other illicit drug use, and were demographically matched, Wetherill and Fromme conducted an alcohol administration (target BrAC of .08 g/dl versus no alcohol) with memory assessments and found that while sober, individuals with and without a history of alcohol-induced blackouts did not differ in memory performance; however, after alcohol consumption, individuals with a history of blackouts exhibited contextual memory impairments, while those without a history of blackouts did not.

Wetherill and colleagues (2012) conducted a follow-up study that used a within subject alcohol challenge followed by two functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) sessions under no alcohol and alcohol (target BrAC of .08 g/dl) conditions. During fMRI scanning, participants completed a contextual memory task. Findings again revealed that individuals with and without a history of fragmentary blackouts did not differ in contextual memory performance or neural activity while sober, yet after alcohol consumption, individuals with a history of fragmentary blackouts showed less neural activation during encoding and recollection of contextual details in prefrontal and parietal regions, suggesting that alcohol had differential effects on frontoparietal brain activity (Wetherill et al., 2012).

Subsequently, Wetherill and colleagues (2013) explored whether frontoparietal abnormalities exist among substance-naïve youth who later transition into heavy drinking and experience alcohol-induced blackouts. Specifically, 60 substance-naïve youth completed fMRI scanning during a go/no-go response inhibition task shown to engage frontal and posterior parietal brain regions (Tapert et al., 2007) at baseline and were followed annually. After approximately five years, youth had either remained substance-naïve (n=20) or had transitioned into heavy drinking and were classified as either alcohol-induced blackout positive (n=20) or alcohol-induced blackout negative (n=20). Groups were demographically matched and youth who experienced alcohol-induced blackouts were matched on follow-up substance use. Although groups did not differ in inhibitory processing performance, prior to initiating substance use, youth who later transitioned into heavy drinking and experienced an alcohol-induced blackout showed greater neural activation during inhibitory processing in frontal and cerebellar regions compared to controls and those who did not experience alcohol-induced blackouts. Further, activation during correct inhibitory processing compared to go responses in the left and right middle frontal gyri at baseline predicted future blackout experience, after controlling for alcohol consumption and externalizing behaviors (Wetherill et al., 2013). Findings from this study suggest that some individuals have inherent vulnerabilities to inhibitory processing difficulties that likely contribute to alcohol-induced memory impairments. Overall, these neuroimaging findings provide strong evidence for neurobiological vulnerabilities to alcohol-induced memory impairments and alcohol-induced blackouts that exist prior to the onset of alcohol use but become more evident after alcohol consumption.

Silveri and colleagues (2014) and Chitty and colleagues (2014) used magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) to examine potential neurochemical differences among individuals who experience blackouts and those who do not. Using MRS in a sample of 23 young adults who were binge drinkers and 31 young adult light drinkers, researchers found in vivo evidence of lower frontal lobe (i.e. anterior cingulate cortex, ACC) gamma amino-butyric acid (GABA) and N-acetyl-apartate (NAA) in binge drinkers than light drinkers, with post hoc analyses revealing that these lower neurochemical profiles were driven by binge drinkers who reported a history of alcohol-induced blackouts (Silveri et al., 2014). Further, in a sample of 113 18–30 year olds (64 individuals with bipolar disorder and 49 healthy comparison controls), reduced hippocampal glutathione, the brain’s most potent antioxidant, concentration was associated with blackout occurrence and severity (Chitty et al., 2014). Chitty and colleagues (2014) interpreted these findings as support for the role of the hippocampus in alcohol-induced memory impairments. Together, these MRS findings indicate that binge drinking and riskier alcohol use affect the neurochemistry of some individuals more than others, which may contribute to the recurrence of and vulnerability to alcohol-induced memory impairments.

Practical and Clinical Implications of Alcohol-induced Blackouts

From a review of 26 empirical studies, Pressman and Caudill (2013) concluded that only short-term memory is impaired during a blackout and that other cognitive functions, such as planning, attention, and social skills, were not affected. Because cognitive functions other than memory are not necessarily impaired during a blackout (Pressman and Caudill, 2013), a critical question is whether or not people are responsible for their behavior while in a blackout. This is often a key factor in alcohol-related crimes, when the perpetrator or victim claim to have no memory for their actions (van Oorsouw et al., 2004). For example, Pressman and Caudill (2013) reference a quadruple murder in which the defendant claimed he had no memory of committing the murders because he was in an alcohol-induced blackout at the time. Applying Daubert legal standards to this case ((Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, 509 U.S. 579 (1993)), the authors concluded that the accused’s blackout could not be used as a viable defense. Equally important, however, may be the memory of a potential victim of a crime. For example, alleged victims of sexual assault may claim they have no memory for events that led up to the sexual activities ((United States v. Pease, Navy-Marine Corps Court of Criminal Appeals 201400165, (2015)). Whereas there is legal precedent to prevent voluntary intoxication and blackouts from being viable defenses against committing a crime (Cunnien, 1986; Marlowe et al., 1999), a remaining question is the extent to which alleged victims in a blackout should be held accountable for their actions, despite their lack of memories. Unquestionably, when a victim is incapacitated from alcohol and unable to provide consent, there are grounds for a conviction of sexual assault. However, as reviewed above, blackouts can occur at BrACs well below the level of incapacitation. If people maintain their ability to make conscious decisions and execute voluntary behaviors while in a blackout, questions remain about whether or not they are responsible for their actions.

It is important to remember that when examining the impact of blackouts, the accused, victim, patient, or research subject is typically being asked to remember not remembering. This is a critical challenge to understanding and studying blackouts, and also raises questions about the accuracy of memories that are reported following a blackout. In an effort to fill in gaps in their memory because of alcohol-induced blackouts, people use a variety of strategies to reconstruct their experiences (Nash and Takarangi, 2011). The most common reconstruction strategy is to ask friends who were present, and who may or may not have also been intoxicated. Consequently, in their quest to learn about their actions while in a blackout, people may be given misinformation from their friends, leading to inaccurate reconstructions of the events. People may also look for photos/videos or other types of physical evidence to help fill gaps in their memories due to blackouts. Regardless of how many different approaches a person takes in order to help reconstruct their memory of what occurred during a blackout, there is rarely a way to validate the memories as accurate because the process of memory reconstruction is inherently fallible.

The fallibility of memory, even in the absence of alcohol or blackouts, has been documented through decades of rigorous experimental and field research. Leading this research, Elizabeth Loftus has authored over 200 books and thousands of peer-reviewed articles which demonstrate the many ways in which memory for events can be distorted or contaminated during the process of recall (Loftus and Davis, 2006; Morgan et al., 2013; Patihis et al., 2013). Provision of misinformation, the passage of time, and being asked or interviewed about prior events can all lead to memory distortions as the individual strives to reconstruct prior events (Loftus and Davis, 2006; Nash and Takarangi, 2011). Consequently, the reliability or accuracy of memories that are recalled following a period of alcohol-induced amnesia are likely to be suspect.

There are also important clinical implications of blackouts, as alcohol-induced blackouts have been associated with psychiatric symptomatology (Bae et al., 2015; Neupane and Bramness, 2013; Winward et al., 2014), as well as feeling embarrassed or distressed when learning about their behavior during a blackout (White et al., 2004). Efforts to reconcile their intoxicated behavior with their personal values may further contribute to significant emotional angst (Wilhite and Fromme, 2015). As such, educating people about the nature and consequences of alcohol-induced blackouts is needed. Although heavy episodic drinking, a common correlate of alcohol-induced blackouts, is often a focus of alcohol prevention programs, rarely are blackouts considered as a target for intervention. For example, a recent study on the effects of a motivational invention on alcohol consumption and blackouts found that the intervention decreased both alcohol consumption and the number of blackouts experienced (Kazemi et al., 2013). Thus, educating people about the factors that contribute to (e.g., predrinking/prepartying; family history of alcohol problems) and consequences of blackouts may help reduce the likelihood of experiencing blackouts and related negative emotional consequences (Wilhite and Fromme, 2015).

Challenges and Future Research

There are several challenges that hinder research on blackouts. First, alcohol-induced blackouts are amnestic periods, and as such, researchers are relying on self-report of alcohol consumption for a period of time that the individual cannot recall. Further, individuals who experienced a blackout often rely on other individuals to help reconstruct the events that occurred during the blackout, but the information from these other individuals is likely unreliable because they may also be consuming alcohol (Nash and Takarangi, 2011). As such, future research should use alternative methodologies to better understand the phenomenology of alcohol-induced blackouts. For example, information might be obtained from a research observer, posing as a confederate, who is not drinking but is present at the drinking event. Also, because short-term memory remains intact, use of ecological momentary assessment with smart phones might also be useful for gathering information about the drinker’s experiences while he or she is in a blackout state. Subsequent interviews could then determine what aspects of those events were remembered and whether they were remembered in the same way that they were reported during the drinking event.

Another complicating factor for research on blackouts is the potential use of other drugs (illicit or prescription) that might also contribute to memory loss. Although several research studies statistically control for or exclude individuals who report co-occurring illicit drug use, research clearly indicates that some individuals who report blackouts also report other drug use (Baldwin et al., 2011; Haas et al., 2015). Thus, researchers must be cautious and account for factors other than alcohol that might contribute to blackouts.

Perhaps the greatest impediment to rigorous tests of alcohol-induced blackouts and behavior is that researchers are not ethically permitted to provide alcohol in sufficient doses to cause a blackout to occur. BrACs of 20 g/dl and above are typically required to induce a blackout, thereby limiting the ability to safely dose research participants to the point of blackout. As such, researchers may consider conducting field studies in order to better characterize and understand alcohol-induced blackouts, as it is quite likely that the events and consequences that occur during a blackout are underestimated given the limits of laboratory research and self-report of events. Finally, given the growing literature on alcohol-induced memory impairments and blackouts, a standardized assessment for alcohol-induced blackouts is sorely needed. Most of the existing research on alcohol-induced blackouts either uses a single item from the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index or the investigator’s own description/definition of an alcohol-induced blackout. Moreover the frequency of occurrence for blackouts is currently measured in widely different ways, including dichotomous measures (e.g., Yes/No blackouts) and proportion of times drinking that blackouts were experienced (e.g., always, sometimes, never). In an effort to better characterize blackouts, researchers should collect detailed information about past and current alcohol consumption patterns, as well as other illicit drug use. It will be important for future studies to conduct a thorough assessment of the alcohol consumption that occurred during the drinking event in which the blackout occurred (i.e., duration of drinking, type of alcohol consumed, pace of consumption), as well as gender and weight, in order to calculate more accurate estimations of BACs. Optimally, actual BrACs or blood draws could be collected to back-extrapolate peak BACs to the time of blackout. This information will enable researchers to statistically control for the direct effects of alcohol consumption and examine factors that influence alcohol-induced blackouts over and beyond the amount of alcohol consumed.

Despite the increase in research on and our understanding of alcohol-induced blackouts, additional rigorous research is still needed. Studies examining potential genetic and environmental influences, as well as their interactions, are clearly warranted given recent research findings of Marino and Fromme (2015). Sex differences in alcohol-induced blackouts are another area in need of study. Although previous research indicates that women are more vulnerable to alcohol-induced blackouts due to the effect of sex differences in pharmacokinetics and body composition on alcohol bioavailability (Rose and Grant, 2010), the influence of biological sex on alcohol-induced blackouts are inconsistent. Specifically, several studies either did not assess sex differences (Clinkinbeard and Johnson, 2013; Sanchez et al., 2015; Wetherill and Fromme, 2011; Wetherill et al., 2013), reported no sex differences (Barnett et al., 2014; Boekeloo et al., 2011; Brister et al., 2011, Wilhite and Fromme, 2015), reported that males reported higher rates of alcohol-induced blackouts (Chartier et al., 2011) or reported that being a female contributed to the likelihood of experiencing an alcohol-induced blackout (Hallett et al., 2013; Schuckit et al., 2015). These inconsistent findings could be due in part to methodological differences across research studies and assessment of alcohol-induced blackouts, and future studies should address this issue. Additional areas for future study include interventions targeting alcohol-induced blackouts, whether the risk for alcohol-induced blackouts increases as individuals age and become more susceptible to memory deficits, and whether there is a “window of vulnerability” such that experiencing an alcohol-induced blackout increases the risk of experiencing another alcohol-induced blackout within a short time frame (akin to second impact syndrome for concussions).

The literature on alcohol-induced blackouts continues to grow, and the recent research reviewed here suggests that there are individual factors that contribute to the occurrence of alcohol-induced memory impairments beyond the amount of alcohol consumed and that alcohol-induced blackouts have consequences beyond memory loss for a drinking episode. Although our understanding of alcohol-induced blackouts has improved dramatically, additional research is clearly necessary. By fine-tuning our approach to studying blackouts, we will improve our understanding of alcohol-induced blackouts, and consequently, be better situated to improve prevention strategies.

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon work supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism under grants K23 AA023894 awarded to Reagan Wetherill and R01 AA020637 awarded to Kim Fromme.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants K23AA023894 (PI: Wetherill) and R01AA020637 (PI: Fromme) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The authors would like to thank Diantha LaVine for her assistance with the artwork.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have not been involved in financial relationships that pose a conflict of interest for this work. The authors are in agreement regarding the content of this manuscript.

References

- Bae HC, Hong S, Jang SI, Lee KS, Park EC. Patterns of Alcohol Consumption and Suicidal Behavior: Findings From the Fourth and Fifth Korea National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (2007–2011) J Prev Med Public Health. 2015;48:142–150. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.14.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin K, Barrowman NJ, Farion KJ, Shaw A. Attitudes and practice of Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (Ottawa, Ontario) paediatricians and residents toward literacy promotion in Canada. Paediatr Child Health. 2011;16:e38–42. doi: 10.1093/pch/16.5.e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Clerkin EM, Wood M, Monti PM, O’Leary Tevyaw T, Corriveau D, Fingeret A, Kahler CW. Description and predictors of positive and negative alcohol-related consequences in the first year of college. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75:103–114. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boekeloo BO, Novik MG, Bush E. Drinking to Get Drunk among Incoming Freshmen College Students. Am J Health Educ. 2011;42:88–95. doi: 10.1080/19325037.2011.10599176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brister HA, Sher KJ, Fromme K. 21st birthday drinking and associated physical consequences and behavioral risks. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25:573–582. doi: 10.1037/a0025209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier KG, Hesselbrock MN, Hesselbrock VM. Alcohol problems in young adults transitioning from adolescence to adulthood: The association with race and gender. Addict Behav. 2011;36:167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitty KM, Lagopoulos J, Hickie IB, Hermens DF. The impact of alcohol and tobacco use on in vivo glutathione in youth with bipolar disorder: an exploratory study. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;55:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinkinbeard SS, Johnson MA. Perceptions and practices of student binge drinking: an observational study of residential college students. J Drug Educ. 2013;43:301–319. doi: 10.2190/DE.43.4.a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunnien AJ. Alcoholic blackouts: phenomenology and legal relevance. Behav Sci Law. 1986;4:364–370. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin DW. Alcohol amnesia. Addiction. 1995;90:315–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1995.tb03779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin DW, Crane JB, Guze SB. Alcoholic “blackouts”: a review and clinical study of 100 alcoholics. Am J Psychiatry. 1969a;126:191–198. doi: 10.1176/ajp.126.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin DW, Crane JB, Guze SB. Phenomenological aspects of the alcoholic “blackout”. Br J Psychiatry. 1969b;115:1033–1038. doi: 10.1192/bjp.115.526.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas AL, Wickham R, Macia K, Shields M, Macher R, Schulte T. Identifying Classes of Conjoint Alcohol and Marijuana Use in Entering Freshmen. Psychol Addict Behav. 2015 doi: 10.1037/adb0000089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallett J, Howat P, McManus A, Meng R, Maycock B, Kypri K. Academic and personal problems among Australian university students who drink at hazardous levels: web-based survey. Health Promot J Austr. 2013;24:170–177. doi: 10.1071/HE13094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzler B, Fromme K. Fragmentary and en bloc blackouts: similarity and distinction among episodes of alcohol-induced memory loss. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64:547–550. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan TM. The impact of excessive alcohol use on prospective memory: a brief review. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2008;1:36–41. doi: 10.2174/1874473710801010036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepola S. Blackout: Remembering the things I drank to forget. Grand Central Publishing; New York, NY: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jellinek EM. Phases in the drinking history of alcoholics: analysis of a survey conducted by the official organ of Alcoholics Anonymous. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1946;7:1–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellinek EM. Phases of alcohol addiction. Q J Stud Alcohol. 1952;13:673–684. doi: 10.15288/qjsa.1952.13.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennison KM, Johnson KA. Drinking-induced blackouts among young adults: results from a national longitudinal study. Int J Addict. 1994;29:23–51. doi: 10.3109/10826089409047367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi DM, Levine MJ, Dmochowski J, Nies MA, Sun L. Effects of motivational interviewing intervention on blackouts among college freshmen. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2013;45:221–229. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer J, Kenney S, Lac A, Pedersen E. Identifying factors that increase the likelihood for alcohol-induced blackouts in the prepartying context. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46:992–1002. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2010.542229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Roh S, Kim DJ. Alcohol-induced blackout. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6:2783–2792. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6112783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftus EF, Davis D. Recovered memories. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2006;2:469–498. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luczak SE, Shea SH, Hsueh AC, Chang J, Carr LG, Wall TL. ALDH2*2 is associated with a decreased likelihood of alcohol-induced blackouts in Asian American college students. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67:349–353. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino EN, Fromme K. Alcohol-induced blackouts and maternal family history of problematic alcohol use. Addict Behav. 2015;45:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe DB, Lambert JB, Thompson RG. Voluntary intoxication and criminal responsibility. Behav Sci Law. 1999;17:195–217. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0798(199904/06)17:2<195::aid-bsl339>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Read JP. Motivational pathways to unique types of alcohol consequences. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010;24:705–711. doi: 10.1037/a0020135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Wardell JD, Read JP. Drinking motives in the prospective prediction of unique alcohol-related consequences in college students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75:93–102. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan CA, 3rd, Southwick S, Steffian G, Hazlett GA, Loftus EF. Misinformation can influence memory for recently experienced, highly stressful events. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2013;36:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundt MP, Zakletskaia LI. Prevention for college students who suffer alcohol-induced blackouts could deter high-cost emergency department visits. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:863–870. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundt MP, Zakletskaia LI, Brown DD, Fleming MF. Alcohol-induced memory blackouts as an indicator of injury risk among college drinkers. Inj Prev. 2012;18:44–49. doi: 10.1136/ip.2011.031724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash RA, Takarangi MK. Reconstructing alcohol-induced memory blackouts. Memory. 2011;19:566–573. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2011.590508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EC, Heath AC, Bucholz KK, Madden PA, Fu Q, Knopik V, Lynskey MT, Lynskey MT, Whitfield JB, Statham DJ, Martin NG. Genetic epidemiology of alcohol-induced blackouts. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:257–263. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupane SP, Bramness JG. Prevalence and correlates of major depression among Nepalese patients in treatment for alcohol-use disorders. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2013;32:170–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patihis L, Frenda SJ, LePort AK, Petersen N, Nichols RM, Stark CE, McGaugh JL, Loftus EF. False memories in highly superior autobiographical memory individuals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:20947–20952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314373110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry PJ, Argo TR, Barnett MJ, Liesveld JL, Liskow B, Hernan JM, Trnka MG, Brabson MA. The association of alcohol-induced blackouts and grayouts to blood alcohol concentrations. J Forensic Sci. 2006;51:896–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2006.00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pressman MR, Caudill DS. Alcohol-induced blackout as a criminal defense or mitigating factor: an evidence-based review and admissibility as scientific evidence. J Forensic Sci. 2013;58:932–940. doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.12134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray AE, Stapleton JL, Turrisi R, Mun EY. Drinking game play among first-year college student drinkers: an event-specific analysis of the risk for alcohol use and problems. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2014;40:353–358. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2014.930151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wardell JD, Bachrach RL. Drinking consequence types in the first college semester differentially predict drinking the following year. Addict Behav. 2013;38:1464–1471. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose ME, Grant JE. Alcohol-induced blackout. Phenomenology, biological basis, and gender differences. J Addict Med. 2010;4:61–73. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181e1299d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryback RS. Alcohol amnesia. Observations in seven drinking inpatient alcoholics. Q J Stud Alcohol. 1970;31:616–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez ZM, Ribeiro KJ, Wagner GA. Binge Drinking Associations with Patrons’ Risk Behaviors and Alcohol Effects after Leaving a Nightclub: Sex Differences in the “Balada com Ciencia” Portal Survey Study in Brazil. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0133646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Heron J, Hickman M, Macleod J, Munafo MR, Kendler KS, Dick DM, Davey-Smith G. Latent trajectory classes for alcohol-related blackouts from age 15 to 19 in ALSPAC. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:108–116. doi: 10.1111/acer.12601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveri MM, Cohen-Gilbert J, Crowley DJ, Rosso IM, Jensen JE, Sneider JT. Altered anterior cingulate neurochemistry in emerging adult binge drinkers with a history of alcohol-induced blackouts. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38:969–979. doi: 10.1111/acer.12346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutske WS, True WR, Scherrer JF, Heath AC, Bucholz KK, Eisen SA, Goldberg J, Lyons MJ, Tsuang MT. The heritability of alcoholism symptoms: “indicators of genetic and environmental influence in alcohol-dependent individuals” revisited. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:759–769. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1999.tb04181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapert SF, Schweinsburg AD, Drummond SP, Paulus MP, Brown SA, Yang TT, Frank LR. Functional MRI of inhibitory processing in abstinent adolescent marijuana users. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;194:173–183. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0823-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulving E. Episodic memory: from mind to brain. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002;53:1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Oorsouw K, Merckelbach H, Ravelli D, Nijman H, Mekking-Pompen I. Alcoholic blackout for criminally relevant behavior. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2004;32:364–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl S, Sonntag T, Roehrig J, Kriston L, Berner MM. Characteristics of predrinking and associated risks: a survey in a sample of German high school students. Int J Public Health. 2013;58:197–205. doi: 10.1007/s00038-012-0409-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherill RR, Castro N, Squeglia LM, Tapert SF. Atypical neural activity during inhibitory processing in substance-naive youth who later experience alcohol-induced blackouts. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;128:243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherill RR, Fromme K. Acute alcohol effects on narrative recall and contextual memory: an examination of fragmentary blackouts. Addict Behav. 2011;36:886–889. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherill RR, Schnyer DM, Fromme K. Acute alcohol effects on contextual memory BOLD response: differences based on fragmentary blackout history. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:1108–1115. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01702.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A, Hingson R. The burden of alcohol use: excessive alcohol consumption and related consequences among college students. Alcohol Res. 2013;35:201–218. doi: 10.35946/arcr.v35.2.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. J Stud Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AM. What happened? Alcohol, memory blackouts, and the brain. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27:186–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AM, Jamieson-Drake DW, Swartzwelder HS. Prevalence and correlates of alcohol-induced blackouts among college students: results of an e-mail survey. J Am Coll Health. 2002;51:117–119. 122–131. doi: 10.1080/07448480209596339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AM, Matthews DB, Best PJ. Ethanol, memory, and hippocampal function: a review of recent findings. Hippocampus. 2000;10:88–93. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(2000)10:1<88::AID-HIPO10>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AM, Signer ML, Kraus CL, Swartzwelder HS. Experiential aspects of alcohol-induced blackouts among college students. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30:205–224. doi: 10.1081/ada-120029874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhite ER, Fromme K. Alcohol-Induced Blackouts and Other Negative Outcomes During the Transition Out of College. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2015;76:516–524. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winward JL, Bekman NM, Hanson KL, Lejuez CW, Brown SA. Changes in emotional reactivity and distress tolerance among heavy drinking adolescents during sustained abstinence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38:1761–1769. doi: 10.1111/acer.12415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]