Summary

Many schools have instituted later morning start times to improve sleep, academic, and other outcomes in response to the mismatch between youth circadian rhythms and early morning start times. However, there has been no systematic synthesis of the evidence on the effects of this practice. To examine the impact of delayed school start time on students’ sleep, health, and academic outcomes, electronic databases were systematically searched and data were extracted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Six studies satisfied selection criteria and used pre-post, no control (n=3), randomized controlled trial (n=2), and quasi-experimental (n=1) designs. School start times were delayed 25 to 60 minutes, and correspondingly, total sleep time increased from 25 to 77 minutes per weeknight. Some studies revealed reduced daytime sleepiness, depression, caffeine use, tardiness to class, and trouble staying awake. Overall, the evidence supports recent non-experimental study findings and calls for policy that advocates for delayed school start time to improve sleep. This presents a potential long-term solution to chronic sleep restriction during adolescence. However, there is a need for rigorous randomized study designs and reporting of consistent outcomes, including objective sleep measures and consistent measures of health and academic performance.

Keywords: students, schools, education, sleep, sleep deprivation, sleep restriction, circadian rhythm, eveningness, start time

Introduction

Research conducted over the past four decades has demonstrated that acquiring adequate sleep and maintaining a sleep schedule that is consistent with physiological circadian rhythmicity is a component of normal growth and development during childhood and adolescence.[1] Adequate sleep is needed to achieve optimal mental and physical alertness, daytime functioning, and learning capacity in youth,[2, 3] qualities that are of particular importance in the school setting.

Although guidelines differ in terms of recommendations for total sleep time,[4] the National Sleep Foundation released recommendations in February 2015 that school-aged children (6 to 13 years) and adolescents (14 to 17 years) obtain at least 9 to 11 hours and 8 to 10 hours of sleep per night, respectively.[5] Yet, by some estimates, only one in ten adolescents meet these recommendations on weeknights.[6, 7] The high prevalence of sleep restriction may be due to early school start times that conflict with the normal developmental shift in circadian biology that favors phase delay (late morning-late day activities and later bedtimes) during puberty development, as indicated by daily endocrine rhythms.[8, 9] In addition to the physiological underpinnings, evening chronotype preference may be driven by social pressures rooted in involuntary (e.g. staying awake to complete homework) or voluntary (e.g. engaging with social media) actions.[10]

The large proportion of adolescents who do not obtain optimal sleep duration [6, 7] is particularly alarming because chronic sleep restriction, defined as partial sleep deprivation, sleep loss, insufficient or deficient sleep, leads to a myriad of health, safety, behavioral, and cognitive and academic deficits. Disrupted sleep-wake cycles and sleep restriction also contribute to pathophysiological effects on the renal, cardiovascular, thermoregulatory, digestive, and endocrine systems.[2, 11] Sleep restriction can lead to insulin resistance and changes in the satiety hormones leptin and ghrelin,[12, 13] all mechanisms for the development of metabolic abnormalities, obesity, and type 2 diabetes.[14–17] Inadequate sleep is also associated with many risky health behaviors, such as lack of physical activity, suicidal ideation, and substance use,[6, 18–20] as well as motor vehicle accidents related to drowsy driving[21, 22] and sport-related injuries.[23]

Sleep restriction also contributes to several cognitive and behavioral problems that adversely impact academic performance and functioning. For instance, adolescents who are chronically sleep restricted perform academically poorer in morning classes and in overall performance,[24] have increased absenteeism and tardiness,[25] and a decreased ability to learn and retain material, actively participate in class, and perform decision-making tasks.[7, 26, 27] Furthermore, sleep compromised adolescents are also more likely to be depressed, anxious, irritable, defiant, apathetic, and impulsive than adolescents who achieve optimal sleep.[28–31]

To address the public health issue of chronic sleep restriction among adolescents, schools have made efforts over the past 15 years to change start times to occur later in the morning to better align with adolescents’ circadian timing, social and environmental pressures, and to improve academic performance. Indeed, numerous cross-sectional and observational studies have suggested the benefit of delayed school start times. These studies usually compared one school district or class with another that used a later start time and revealed that adolescents in schools with later start times have less daytime sleepiness and sleep restriction,[8, 32–35] improved sleep quality,[36] better behavior, attention and concentration in class,[34, 35] less tardiness,[37] higher academic achievement in some[35, 38] but not all schools,[39] and fewer motor vehicle accidents.[21] The effects of later school start times compared favorably with other educational interventions in terms of overall cost and commensurate academic success.[40]

While these studies suggest improvements relative to other schools or classrooms, interpretation of these findings is limited because they do not include assessment of within-subjects changes in sleep or other outcomes. Further, given the public advocacy for delayed school start times,[41] the recent policy statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics to delay the start of class to 8:30 a.m. or later,[42] and some estimates that over 80 U.S. school districts have already adopted later school start times,[43] a review of the experimental literature is needed. Although others have written reviews with a similar focus, one was published in a journal that was not peer-reviewed,[44] and a second consisted of a narrative review,[45] a method that is not systematic in terms of the literature search or appraisal of quantitative data. Further, the American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement has called for research to document the effects of changes in school start times over time.[42] Thus, the purpose of this paper is to systematically review the evidence on the impact of delayed school start time interventions on students’ sleep, health, and academic outcomes.

Methods

Literature Search

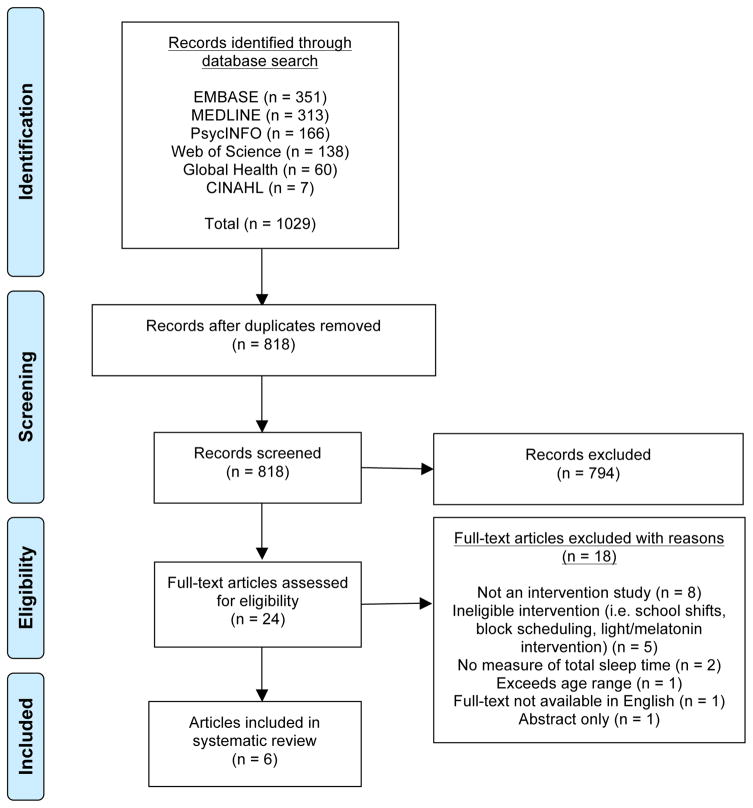

We conducted a systematic review to synthesize the results of experimental research. The review began with a search of the literature to locate articles that used quantitative methods to assess the impact of delayed school start time interventions among youth. Relevant sources were identified by the first author through searches of the following electronic bibliographic databases in May 2014 with the assistance of a medical librarian to ensure balance of sensitivity and specificity: Ovid EMBASE, Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid PsycINFO, Web of Science, Global Health, and CINAHL. The results were limited to full-article peer-reviewed publications written in English. The search terms included the following keywords: “Students” AND “Schools OR Education” AND “Sleep Deprivation OR Sleep OR Circadian Rhythm OR School Start Time OR Start Time OR Start Late OR Start Delay OR Start Stagger OR Start Early OR Eveningness OR Wakefulness”. We did not search for intervention-related terms, as there is no clear way to capture intervention studies, especially those that do not use a randomized design. An example of the full search strategy is available (“See supplementary Table S1”). Results were not limited to chronological age of the student or year of publication. To identify any articles that may have been missed during the literature search, reference lists of candidate articles were reviewed, yielding no additional articles. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting flowchart was used to document the literature search process (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of literature search

Study Selection Criteria

The titles and abstracts of all citations identified by the literature search were reviewed. Potentially relevant published articles reporting their selection criteria were retrieved. The selection criteria were specified in advance and included the following: 1) published in English in a peer-reviewed journal; 2) available in full-text; 3) primary or secondary school-aged youth were the subject of research; 4) experimental study design (i.e. randomized controlled trial (RCT), quasi-experimental, pre-post no control); 5) reported total sleep time; and 6) studies that examined the impact of delayed school start time on the same subjects. Observational, correlational and descriptive studies were excluded, as were technical reports, reviews, editorials, unpublished manuscripts, dissertations, and abstracts. If multiple articles were available from a single study, the most recently published article or article containing the most comprehensive description of study characteristics was selected for review.

Article Review and Data Extraction

As suggested by a recent review of knowledge synthesis techniques,[46] the PRISMA reporting guideline was adopted for this article to improve transparency and reduce the risk of bias[47] (see Figure 1).

Data extraction was conducted by using a data display matrix to obtain reliable and consistent data from the primary studies. Information was extracted pertaining to study characteristics: author, year, country, study aim, school description (student body, type of school, location), sample description (mean age, age range, percent girls, percent non-white, sample size), study description (study design, sampling method, intervention intent (research study or policy change)), and intervention description (start time change, minutes of delayed start, treatment length, dates of data collection, sleep data collection instrument). A second data display matrix was created to extract data related to the study outcomes, including sleep-related outcomes (e.g. bed time, wake time, total sleep time (sleep duration), other sleep characteristics), health-related outcomes (e.g. body mass index (BMI), depression, psychosocial health, use of school nurse), and academic-related outcomes (e.g. academic achievement, tardiness, absenteeism, staying awake in class). Where reported, we extracted the results of statistical tests (95% confidence intervals or p-values) and considered the suitability for meta-analysis of the effects of delayed school start time on total sleep time. Additional information was extracted pertaining to group characteristics, including effects of delayed start time by gender, race/ethnicity, grade level, and day vs. boarding students. We also included evidence of non-significant findings.

Data Synthesis

Studies were categorized based on their year of publication and geographical affiliation. Where available, outcomes for each study were summarized and compared in terms of the net change in sleep, health, and academic characteristics. Due to significant variation in study designs, participants, and treatment lengths, we were unable to conduct a meta-analysis. Furthermore, many studies failed to report confidence intervals for the main outcomes, thus we would have been unable to construct a forest plot.

Results

Literature Search

A total of 1029 articles were identified and imported into Endnote software (Figure 1). Duplicates were removed via the Endnote duplicate function and any remaining duplicates were manually removed, leaving a total of 818 articles. A thorough review of all article titles and abstracts was conducted to identify articles to review in full-text (N = 24). The majority of articles excluded after review of their title or abstract was due to a cross-sectional design or not related to a delayed start time intervention. After full-text review, 18 of the 24 articles were excluded most often due to a non-experimental study design (e.g. observational, naturalistic, comparative design) or an ineligible intervention that assessed changes in school shifts, block scheduling, or the effects of a light intervention on melatonin. Thus, a final sample of 6 articles was identified for this review.

Characteristics of Selected Studies

The authors of all studies sought to examine the impact of a delayed school start time on at least one of the following outcomes: sleep characteristics (sleep patterns, sleepiness, sleep duration), attention performance, academic achievement, motor vehicle crashes, mood, and health-related outcomes (“See table 1”). The type of schools varied from private (n=2) to public (n=4) ownership and high school (n=4) to middle school (n=2). For those students enrolled in the primary studies, the mean sample size ranged from 47 to 10,656 with the majority of sample sizes fewer than 600 students. Participants’ mean age varied widely across studies, from 10.8 to 16.4 years, although all but one study had a mean age of 13 years or older upon enrollment. In samples where the gender was reported, most had a slight oversampling of girls. Geographically, three studies were conducted in the United States and one each in China, Israel, and Norway.

Table 1.

Characteristics of reviewed studies

| Author (Country) | Aim | School Description | Sample Description | Study Description | Intervention Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boergers, Gable, & Owens, 201452 (USA) | To examine the impact of a very modest (25 min) experimental delay in school start time on students’ sleep patterns, sleepiness, mood, and health-related outcomes at a competitive independent boarding school. |

Students (n): 849 boarding | 203 day | Total: 1052 School type: Private coeducational residential high school |

Mean age: 15.6 years Grade(s): 9–12 Girls: 59% Non-white: 48% (mostly Asian, 31%) Sample size (n)a: 197 |

Study design: Pre-post, no control Sampling method: Convenience; all students invited to participate Intervention recipients: Research study, entire school |

Start time change: 8:00am → 8:25am Minutes of delayed start: 25 (classes ended 25 mins later) Treatment length: 4 months; December 2010 – March 2011 Dates of data collection: November 2010, April 2011 Sleep data collection instrument: S-R; School Sleep Habits Survey |

|

| |||||

| Danner & Philips, 200849 (USA) | To assess the effects of delayed high school start times on sleep and motor vehicle crashes |

Students (n): NR School type: Public high school Location: Kentucky county |

Mean age: NR Grade(s): 9–12 (ages 14–18 years) Girls: NR Non-white: NR Sample size (n)a: 10,656 |

Study design: Pre-post, no control Sampling method: Convenience Intervention recipients: Policy change, county-level |

Start time change: 7:30am → 8:30am Minutes of delayed start: 60 Treatment length: April 1998 onward Dates of data collection: April 1998 and April 1999 Sleep data collection instrument: S-R; Epworth Sleepiness Scale |

|

| |||||

| Li et al., 201350 (China) | To examine the effectiveness of a school-based sleep intervention scheme using a comparative cross- sectional analysis of pre- and post- intervention surveys. |

Students (n): 586 School type: Public primary school Location: Shanghai |

Mean age: 10.81 (SD 0.33) years Grade(s): 4–5 (ages 9.6– 12.0 years) Girls: 49.2% Non-white: NR Sample size (n)a: 553 |

Study design: RCT, 3 group (control, intervention 1, intervention 2) × 2 times (baseline, 2 year follow- up) design Sampling method: 6/10 primary schools selected based on inclusion criteria: 1) no differences in sleep duration and daytime sleepiness between schools; 2) performing the same school schedule, including school starting time (7:30am) and school finishing time (3:30pm); 3) be similar in term of socioeconomic background and student educational achievements. Intervention recipients: Research study, entire schools |

Start time change: Intervention 1: 7:30am → 8:00am Intervention 2: 7:30am → 8:30am (classes ended 30 and 60 mins later, respectively) Minutes of delayed start: Intervention 1:30 Intervention 2: 60 Treatment length: 2 years; September 2007 – September 2009 Dates of data collection: September 2007, September 2009 Sleep data collection instrument: S-R; Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire |

|

| |||||

| Lufi, Tzischinsky, & Hadar, 201151 (Israel) | To examine the impact of delaying school starting time one hour on sleep duration and attention performance. |

Students (n): 47 School type: Public school Location: Northern Israel |

Sample mean age: 13.78 (SD 0.82) years Grade(s): 8 Girls: 57.45% Non-white: NR Sample size (n)a: 47 (Control: 21; Intervention: 26) |

Study design: RCT, 2 group (control and intervention) × 2 times (after week 1 of intervention and after week 2 of normal schedule) Sampling method: 2 classes chosen at random to be the control and intervention groups Intervention recipients: Research study, 2 classes in school |

Start time change: 7:30am → 8:30am (classes ended 60 mins later) Minutes of delayed start: 60 Treatment length: 1 week Dates of data collection: NR Sleep data collection instrument: Objective; Actigraph | S-R; Sleep diary |

|

| |||||

| Owens, Belon, & Moss, 201053 (USA) | To assess the impact of a delay in school start time from 8:00 to 8:30am at an independent school in the northeastern United States. |

Students (n): 357 School type: Independent coeducational college preparatory boarding and day school Location: Southern New England *Note: School had a lights-out schedule and procedure for dormitory students, ranging from 10:30pm – 11:30pm in grades 9, 10, and 11. |

Mean age: 16.4 years Grade(s): 9–12 Girls: 57.3% Non-white: 18% (school total, not sample) Sample size (n)a: 225 |

Study design: Pre-post, no control Sampling method: Convenience Intervention recipients: Research study, entire school |

Start time change: 8:00am → 8:30am (classes ended at normal time (3:00pm four days/wk; 1:00pm on Wednesdays; 11:00am on Saturdays). Minutes of delayed start: 30 Treatment length: 2 months; January 2009 – March 2009 Dates of data collection: December 25, 2008 (baseline), March 5, 2009 (follow-up) Sleep data collection instrument: S-R; Sleep Habits Survey |

| Vedaa, Saxvig, & Wilhelmsen-Langeland, 201248 (Norway) | To investigate the effects of delayed school start time for only one day of the week. |

Students (n): NR School type: Junior high school Location: Norway |

Mean age: NR Grade(s): 10 (ages 13–16 years) Girls: Intervention: 54.5%; Control: 35.3% Non-white: NR Sample size (n)a: 106 (Control: 51; Intervention: 55) |

Study design: Quasi-experimental (control group but not randomized) Sampling method: 2 schools, 2 classes per school. One school selected for intervention group, other served as control group Intervention recipients: School policy change, 2 classes in each school |

Start time change: 8:30am → 9:30am on Mondays Minutes of delayed start: 60 minutes, only on Mondays Treatment length: 2 years Dates of data collection: February and March Sleep data collection instrument: S-R; Karolinska Sleepiness Scale; Sleep diary |

Where possible, sample size is identified as those participants completing both time points from which the analyses are derived.

Abbreviations: Mins: Minutes; NR: not reported; RCT: randomized clinical trial; S-R: self-report.

Studies reported pre-post, no control (n=3), RCT (n=2), and quasi-experimental (n=1) designs. Most studies employed a convenience sampling recruitment technique. Two studies reported on the outcomes of a policy change in later school start times,[48, 49] whereas the remainder altered start times for experimental research purposes; it is unknown if the later start times were continued after the interventions concluded. All studies had a delayed start that ranged from 25 to 60 minutes, but treatment lengths varied from 1 week to indeterminate. Sleep-related data were collected by each study using a self-reported instrument, and one study also employed an objective measurement of sleep (i.e. actigraphy).

Outcomes

All six studies reported on the effect of delayed school start time on sleep outcomes; three reported on health-related outcomes; and five studies reported academic-related outcomes (“See table 2”).

Table 2.

Sleep, health and academic outcomes of reviewed interventions

| Author | Sleepa | Health | Academic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boergers, Gable, & Owens, 201452 |

Bedtime: Pre: 11:48pm (1:03) | Post: 11:44pm (1:06) | Change: 0:04 Wake time: Pre: 7:02am (0:34) | Post: 7:26am (0:36) | Change: 0:24 (p ≤ .001) Total sleep time: Pre: 7:01 (1:00) | Post: 7:30 (1:12) | Change: 0:29 (p ≤ .001) Weekend total sleep time (Saturday night): Pre: 9:04 (1:16) | Post: 9:06 (1:15) | Change: 0:02 Napped on school days: Pre: 44% | Post: 33% (p ≤ .01) |

Visits to school clinic for fatigue-related symptomsc: NS Depressiong: Pre: 10.98 | Post: 10.12 (p ≤ .001) Weekly caffeine use (n per week)g: Pre: 7.62 | Post: 5.89 (p < .05) |

Academic achievement (received B or better): Pre: 93% | Post: 91% Tardiness: Pre: 25% | Post: 16% (p < .05) Presenteeism (sleepiness/falling asleep in class): Pre: 72% | Post: 55% (p ≤ .001) Too tired to do schoolwork Pre: 76% | Post: 61% (p ≤ .001) Too tired to play sports Pre: 45% | Post: 44% Too tired to socialize Pre: 45% | Post: 38% |

|

| |||

| Danner & Philips, 200849 |

Total sleep time: Change: 0:30 (Grade 12) (p ≤ .001) Weekend oversleepf (Friday night) Pre: 1:54 | Post: 1:06 | Change: −0:48 (p ≤ .001) Sleepiness Scaleg Pre: 8.9 | Post: 8.2 (p ≤ .001) |

Too tired to play sportsc: NS Hours spent on homeworkc: NS Participation in school sportsc: NS Participation in organized community sportsc: NS Music activitiesc: NS Volunteer workc: NS Hanging out with friendsc: NS |

|

|

| |||

| Li et al., 201350 |

Bedtime: Control: Pre: 9:19pm (0:35) | Post: 9:32pm (0:34) | Change: 0:13 (p ≤ .001) Intervention 1: Pre: 9:20pm (0:31) | Post: 9:34pm (0:40) | Change: 0:14 (p ≤ .001) Intervention 2: Pre: 9:25pm (0:26) | Post: 9:37pm (0:37) | Change: 0:12 (p ≤ .001) Wake time: Control: Pre: 6:54am (0:23) | Post: 7:01am (0:23) | Change: 0:07 Intervention 1: Pre: 6:52am (0:22) | Post: 7:13am (0:28) | Change: 0:21 (p ≤ .001) Intervention 2: Pre: 6:42am (0:20) | Post: 7:16am (0:25) | Change: 0:34 (p ≤ .001) Total sleep time: Control: Pre: 9:17 (0:44) | Post: 9:01 (0:40) | Change: −0:16 (p ≤ .001) Intervention 1: Pre: 9:20 (0:38) | Post: (0:40) | Change: 0:26 (p ≤ .001) Intervention 2: Pre: 9:18 (0:35) | Post: 9:56 (0:40) | Change: 0:38 (p ≤ .001) Daytime sleepiness (%): No/Rarely: Control: Pre: 64 (40.7) | Post: 71 (37.1) Intervention 1: Pre: 76 (35.1) | Post: 87 (42.1) Intervention 2: Pre: 53 (35.0) | Post: 86 (54.0) Sometimes: Control: Pre: 56 (35.4) | Post: 50 (26.3) Intervention 1: Pre: 82 (38.4) | Post: 62 (29.1) Intervention 2: Pre: 58 (38.0) | Post: 34 (21.3) Frequently: Control: Pre: 38 (23.9) | Post: 71 (36.6) Intervention 1: Pre: 57 (26.7) | Post: 59 (28.8) Intervention 2: Pre: 41 (27.0) | Post: 39 (24.7) (p ≤ .01) for interventions 1 & 2 vs. Control for daytime sleepiness score |

BMI (kg/m2): Control: Pre: 17.46 ± 2.99 | Post: 17.53 ± 2.99 Intervention 1: Pre: 17.69 ± 3.33 | Post: 17.61 ± 3.33 Intervention 2: Pre: 18.36 ± 3.98 | Post: 18.04 ± 3.98 |

|

|

| |||

| Lufi, Tzischinsky, & Hadar, 201151 |

Bedtimee: Control: Pre: 10:58pm (0:23) | Post: 11:04pm (0:35) | Change 0:06 Intervention: Pre: 10:41pm (0:21) | Post: 10:42pm (0:35) | Change: 0:01 Wake timee: Control: Pre: 6:27am (0:23) | 6:22am (0:19) | Change: −0:05 Intervention: Pre: 7:07am (0:16) | Post: 6:13 am (0:13) | Change: −1:06 (p ≤ .01) Total sleep timee: Control: Pre: 7:29am (0:11) | Post: 7:18am (0:19) | Change: −0:11 Intervention: Pre: 8:26am (0:13) | Post: 7:31am (0:19) | Change: −1:05 (p ≤ .01) Sleep efficiencyb: Control: Pre: 92.43%| Post: 94.50% (p < .05) Intervention: Pre: 95.72%| Post: 96.94% (p < .05) (p ≤ .01) for intervention vs. control for wake time; (p < .05) for intervention vs. control for TST |

Overall attention levelg

(mean, SD): Control: Pre: −0.17 (1.03) | Post: −1.18 (0.77) (p ≤ .01) Intervention: Pre: −1.13 (0.64) | Post: −1.37 (0.53) (p ≤ .01) (p < .05) for intervention vs. control for overall attention level |

|

|

| |||

| Owens, Belon, & Moss, 201053 |

Bedtime: Pre: 11:39pm (0:51) | Post: 11:21pm (1:04) | Change: −0:19 (p ≤ .001) Wake time: Pre: 6:54am (0:29) | Post: 7:25am (0:32) | Change: 0:31 (p ≤ .001) Total sleep time: Pre: 7:07 (0:46) | Post: 7:52 (1:13) | Change: 0:45 (p ≤ .001) Weekend bedtime: Pre: 12:56am (1:03) | Post: 12:33am (0:51) | Change: −0:23 Weekend wake time: Pre: 10:22am (1:18) | Post: 10:20am (1:11) | Change: −0:02 Weekend total sleep time (Saturday night): Pre: 9:32 (1:46) | Post: 9:20 (1:27) | Change: −0:12 Weekend oversleepf: Pre: 3:28 | Post: 2:55 | Change: −0:33 (p ≤ .001) (95% CI 0:19 – 0:46) Rarely or never getting enough sleep: Pre: 69.1% | Post: 33.7% (p ≤ .001) Never being satisfied with sleep: Pre: 36.8% | Post: 9.2% (p ≤ .001) Never getting a good night’s sleep: Pre: 28.6% | Post: 11.9% (p ≤ .001) Sleep-Wake Behavior Problems Scaleg: Pre: 31.5 | Post: 25.6 (p ≤ .001) Daytime sleepiness: Pre: 49.1% | Post: 20.0% (p ≤ .001) Takes naps at least sometimes: Pre: 52.4% | Post: 36.3% (p ≤ .001) Require assistance to wake up in the morning (e.g., alarm clock): Pre: 96.6% | Post: 89.0% (p ≤ .001) |

Visit health center for fatigue-related symptoms: Pre: 15.3% | Post: 4.6% (p < .05) Rest visits to health center (n): Pre: 69 | Post: 30 (p < .05) Physician visits (n): Pre: 54 | Post: 48 (NS) Depressed mood scoreg: Pre: 1.84 | Post: 1.56 (p ≤ .001) Somewhat unhappy or depressed: Pre: 65.8% | Post: 45.1% (p ≤ .001) Irritated or annoyed: Pre: 84.0% | Post: 62.6% (p ≤ .001) |

Academic achievement (B’s or better): Pre: 87.1% | Post: 82.2% (NS) Tardiness: Pre: 36.7% | Post: 22.6% (p ≤ .001) Presenteeism (struggled to stay awake during class): Pre: 85.1% | Post: 60.5% (p ≤ .001) Too tired to do schoolwork: Pre: 90.0% | Post: 66.2% (p ≤ .001) Fell asleep during morning class: Pre: 38.9% | Post: 18.0% (p ≤ .001) Late to class owing to oversleeping (n): Pre: 80 | Post: 44 (p < .05) |

| Vedaa, Saxvig, & Wilhelmsen-Langeland, 201248 |

Total sleep timed

(Pre=Saturday night | Post=Sunday night): Control: Pre: 8:52 (1:47) | Post: 6:20 (1:42) | Change: −2:33 (2.23) Intervention: Pre: 8:43 (2:03) | Post: 7:26 (1:25) | Change: −1:17 (2.38) (p < .05) for intervention vs. control for TST Bedtimed (Pre=Saturday night | Post=Sunday night): Control: Pre: 2:17am (1:47) | Post: 12:09am (1:18) | Change: −2:08 Intervention: Pre: 1:47am (1:40) | Post: 11:57pm (1:25) | Change: −1:50 Sleep onset latencyd (Pre=Saturday night | Post=Sunday night): Control: Pre: 0:11 (0:15) | Post: 0:34 (0:42) Intervention: Pre: 0:15 (0:14) | Post: 0:23 (0:25) (p < .05) for intervention vs. control for sleep onset latency Daytime sleepinessg: Controld: Pre: 4.9 (2.2) | Post: 5.0 (1.8) Interventiond: Pre: 4.5 (5.2) | Post: 4.0 (1.8) No significant difference between groups |

Positive affect (mean, SD): Controld: Pre: 28.6 (9.0) | Post: 27.4 (6.0) Interventiond: Pre: 26.3 (7.1) | Post: 26.9 (6.2) No significant difference between groups Negative affect (mean, SD): Controld: Pre: 14.5 (4.7) | Post: 14.0 (3.7) Interventiond: Pre: 13.2 (3.1) | Post: 12.8 (3.4) No significant difference between groups |

Reaction test timeg: Lapses (mean, SD): Controld: Pre: 9.7 (10.6) | Post: 11.1 (11.2) Interventiond: Pre: 14.6 (19.1) | Post: 7.3 (9.8) Median (SD): Controld: Pre: 270.6 (53.0) | Post: 273.1 (61.9) Interventiond: Pre: 322.1 (140.2) | Post: 273.0 (56.2) (p < .05) for intervention vs. control for number of lapses; (p < .05) for better performance in median reaction time for intervention vs. control |

Unless stated otherwise, values are reported in HH:MM. All data pertain to weeknights unless stated differently. Data are expressed as mean (SD).

Sleep efficiency: reported in percentages using the following formula: (sleep time/time in bed × 100).

Mean values were not reported in manuscript.

Did not compare pre-post values for statistical significance.

Values are reversed as baseline was during the intervention; negative number indicates improvement.

Difference between school day and non-school day wake times.

Lower values of the scale are favorable.

Abbreviations: BMI: body mass index, CI: confidence interval; NS: non-significant; SD: standard deviation; TST: total sleep time.

Effects of Delayed School Start Time on Sleep

Total Sleep Time

All six studies reported the effects of delayed school start time on weekday total sleep time, the main outcome observed in our review. Relative to pre-intervention, there was a significant positive net change in all studies, indicating an increase in the total minutes of sleep. The net increase ranged from an additional 25 minutes to 77 minutes (1:17) of sleep per weeknight. For those studies employing a control condition,[48, 50, 51] there was a significant difference between intervention and control groups in total sleep time, with the intervention group having a longer sleep duration. This finding was confirmed by the one study that used actigraphy to objectively measure sleep, noting a net increase in total sleep time for intervention versus control condition (65 min. vs. −11 min., p ≤ .01), and a sleep efficiency of 97% for the intervention group.[51]

Changes in weekend total sleep time were evaluated in three studies that used a pre-post, no control design.[49, 52, 53] The results were mixed in that two studies did not report a significant difference in weekend total sleep time, whereas one study reported a significant decrease of 48 minutes of weekend total sleep time.[49]

Bedtime

Five studies[48, 50–53] evaluated the effects of delayed school start times on bedtime. Three studies[48, 51, 52] found either no difference or earlier bedtimes in the intervention group before and after the delayed start time intervention. However, two studies reported a modest, but significant change in bedtimes, ranging from a later bedtime of 12 to 14 minutes[50] to an earlier bedtime of 19 minutes.[53] Of these studies, those that used a randomized design[50] [48, 51] reported no significant difference in bedtime between the control and intervention groups after the delayed start time, suggesting students went to at the same time regardless of their assigned experimental condition.

Wake Time

Four studies reported the effect of delayed school start time on wake times,[48, 50–53] and each found a significant net delay in wake times. Relative to pre-intervention assessments, wake times increased from 21 minutes to 66 minutes (1:06) later. One study[53] also reported on the effect of delayed school start time on weekend oversleep, or the difference between school day and non-school day wake times, and found a significant decrease of 33 minutes.

Daytime Sleepiness and Sleep Satisfaction

Five studies[48–50, 52, 53] evaluated the effect of delayed start times on measures of daytime sleepiness, including overall sleepiness, napping and assistance required to wake up in the morning (e.g. alarm clock). Each study found a significant improvement in measures of daytime sleepiness, with the exception of one that found no significant difference between intervention and control groups in improvements of daytime sleepiness.[48] Owens and colleagues reported change in sleep satisfaction and found significant improvements in perceptions of getting a good night’s sleep, getting enough sleep, being satisfied with sleep, and fewer sleep-wake behavior problems.[53]

Effects of Delayed School Start Time on Health-related Outcomes

Healthcare Utilization

One study[52] reported no significant decrease in the number of visits to a school clinic for fatigue-related symptoms. Yet another study[53] reported significantly fewer visits to the health clinic to rest (69 to 30 visits) and for fatigue-related symptoms (15.3% to 4.6%) upon post-intervention assessment. However, the authors of this study found no significant difference in number of physician visits.

Depression and Affect

Two studies[52, 53] that used a pre-post, no control design found significant decreases in the depression scale, depressed mood score, and proportion of students who were irritated or annoyed relative to post-intervention. However, one quasi-experimental study[48] did not find a significant difference between the intervention and control groups in terms of positive or negative affect.

BMI

One study conducted by Li and colleagues evaluated the effects of delayed school start time on BMI. The authors found a decrease in BMI for the intervention groups and an increase in the control group, but this finding was not statistically significant.[50]

Caffeine Use

One study[52] reported the effect of delayed school start time on weekly caffeine use and found a significant decrease in the consumption of caffeinated beverages per week (7.62 to 5.89 beverages per week, p<.05).

Effects of Delayed School Start Time on Academic Outcomes

Academic Achievement, Attendance, and Attention

The two studies[52, 53] that evaluated the effects of delayed school start times on academic achievement found no significant difference in self-reported grades of B or higher from pre- to post-intervention. However, these two studies reported significant declines in tardiness, presenteeism (struggling to stay awake during class), and Owens and colleagues reported declines in falling asleep during class and arriving late to class due to oversleeping.[53] Both studies also found that significantly fewer students reported being too tired to complete schoolwork from pre- to post-intervention. However, one other study found no significant difference in the amount of hours students spent on homework.[49]

In addition, one other study found significant improvements in attention levels in class following the delayed school start time.[51] Another noted improved reaction test time when comparing control and intervention groups post-intervention.[48]

Extracurricular Activities

The two studies[49, 52] that evaluated the effects of delayed school start times on whether students were too tired to play sports found no significant change. Similarly, Danner & Phillips (2008) examined a number of other extracurricular activities, and found no significant difference in terms of participation in music activities, volunteer work, or socializing with friends from pre- to post-intervention. The latter findings was also noted by Boergers and colleagues.[52]

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review conducted to evaluate and examine the effect of delayed school start times on sleep, health and academic parameters. Our review of primary experimental studies published in peer-reviewed journals provides initial, cumulative evidence that delaying school start times can be an effective method to improve important sleep outcomes, such as total sleep time and reduce daytime sleepiness; health outcomes, including reduced depression and caffeine use; and academic outcomes, such as tardiness and staying awake in class. These findings suggest that delayed school start times can increase sleep duration in adolescence with corresponding effects on markers of improved health and classroom engagement and behavior. To achieve these outcomes, we support the recent American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement[42] to delay middle and high school start times to 8:30 a.m. or later to become congruent with evening preference chronotype during adolescent years.[1]

Despite the range of outcomes each study reported, all of the studies reported total sleep time and observed a significant increase in sleep duration. The number of minutes school was delayed ranged from 25 to 60 minutes, and correspondingly, students’ increased their total sleep time from 25 to 77 minutes, suggesting a clinically meaningful dose-response relationship. Importantly, among the studies that examined bedtimes and wake times, authors found delays only in wake times while bedtimes had either no change or were earlier. This provides evidence countering the hypothesis that students will simply stay awake later if school start time is delayed, and verifies the developmental shift in circadian timing that favors phase delay during later childhood.[8] Increased sleep duration also contributed to reductions in daytime sleepiness (e.g. napping, overall sleepiness), which has implications for enhancing engagement in learning and achieving success in school due to improved cognitive functioning, problem solving, attention, decision-making, memory and creativity.[2, 7, 26, 27, 37, 54, 55]

Consistent with these explanations, our review found improved school-related outcomes following a delayed school start time intervention including decreased tardiness, presenteeism, falling asleep in class, being too tired to do homework, and improved reaction time; similar result have been observed in cross-sectional or observational studies employing a non-experimental design.[7, 21, 26] Interestingly, the finding that sleep duration did not change or significantly decreased for total weekend sleep time after the intervention suggests that students were not “binge-sleeping” and did not experience the jet-lag effect associated with weekend oversleep due to accumulated sleep debt over the course of the week, which has been shown to adversely impact school performance.[55] Delayed school start times also improved reaction time, which has implications for mitigating drowsy driving-related motor vehicle accidents. For instance, one observational study comparing two neighboring school districts in Virginia found student drowsy driving-related car crashes were 41% higher in the district that did not have a 75-minute delayed start.[21]

Although surrogate markers of academic achievement significantly improved relative to baseline or control condition, the two studies examining changes in self-reported grades found no overall improvement. However, because the findings were derived from self-report data and occurred in private boarding schools, results may be biased or not generalizable to the general population. Nonetheless, since students’ academic success, and public school funding, is often predicated on grades and standardized testing scores, and non-experimental studies provide initial evidence that adolescents with better grades have a longer sleep duration,[6] the importance of testing these outcomes in future studies cannot be overstated.

Overall findings regarding changes in health-related outcomes were mixed with some studies reporting no change in health care utilization for fatigue-related visits and no change in BMI, while others observed a significant reduction in depression and caffeine use. However, too few studies were available to make substantive inferences in this domain. To illustrate this point, one study reported a decrease in BMI for the youth who had a delayed school start time compared with the control condition.[50] However, this finding was not statistically significant.

Despite the benefits of later school start times, school districts may encounter barriers related to modifying transportation schedules and the associated costs, for families where older siblings provide childcare for younger sibling, and delay of sports, social activities, part-time employment, and other afterschool extracurricular activities.[45, 56] With regard to the latter concern, our study found no difference following the delayed start time intervention among those studies that examined participation in afterschool activities. Another concern is that students may stay awake later in order to complete homework or socialize, however two of the reviewed studies found that significantly fewer students reported being too tired to complete schoolwork from pre- to post-intervention, and no studies found students went to bed at a later time following the intervention. Nevertheless, instituting a delay in school start times is achievable with sufficient strategizing and preparation[45], as demonstrated by several school districts[57, 58], and internet-based resources exist that address these barriers and provide guidance for school districts considering implementing a later school start time policy (e.g. www.SchoolStartTime.org; www.StartSchoolLater.net). Involving key players and gaining support of adolescents, parents, teachers, coaches, administrators, transportation directors, sleep professionals, and school boards is critical to ensuring success.

However, before suggestions are heeded for widespread dissemination and implementation of delaying school start times, additional experimental and more rigorous research is needed to determine the effectiveness of delayed school start times. Although the studies included in this review provide evidence that delayed school start times improve total sleep time, half of the studies had a non-randomized study design, and most lacked a reliable and objective measure of sleep. Furthermore, few studies examined the same outcomes in terms of health indicators (i.e., BMI) or academic parameters (i.e., test scores) to comment extensively on those outcomes. In light of these limitations, future studies ought to incorporate a randomized study design, use objective measures to quantify sleep architecture and duration (i.e., actigraphy), and examine the impact of delayed school start time on diverse student populations as well as changes in sleep architecture. Results of outcomes including total sleep time, BMI and academic performance, in particular, are warranted to assess whether delayed school start time can improve test scores while also serving as a mechanism of obesity prevention, and provide robust evidence to advocate for a national public policy debate on delaying school start times.

In addition to the methodological limitations of the primary studies included in this review, our findings must be interpreted in the context of the following limitations. First, although exhaustive search methods were used to eliminate any potential bias, it is possible that not all quantitative studies were identified. In addition, the exclusion of unpublished and grey literature may have contributed an element of publication bias, with potential implications for the robustness of the findings, but such studies may have lower methodological quality[59] and likely would not have used a within-subjects design. Furthermore, the school characteristics were omitted from several of the reviewed studies, potentially influencing the generalizability of the findings to other contexts.

In summary, the cumulative evidence from our systematic review indicates that delayed school start time interventions increase total sleep time, and correspondingly, wake times, therefore presenting a potential long-term solution to chronic sleep restriction during adolescence. This study also verifies the wealth of non-experimental research suggesting the importance of delayed school start times, particularly during adolescence, to improve cognitive performance, academic functioning, mood and health; all faculties that affect students, as well as their peers, teachers, and families. Nonetheless, additional experimental research is needed to examine the effectiveness of these interventions on academic and health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Table S1: Literature search terms and strategy for OVID databases

Practice Points.

Delaying middle and high school start time to 8:30am or later can be an effective method to:

improve important sleep outcomes in adolescence, including weeknight total sleep time and reduce daytime sleepiness;

improve health and academic outcomes, such as depression, caffeine use, tardiness to class and staying awake in class; and

circumvent changes in weeknight bedtime or reduced participation in extracurricular activities.

Research Agenda.

Future studies of delayed school start time are needed to:

examine the effectiveness of delaying school start time on sleep, health, and academic outcomes using a randomized study design;

assess academic- and BMI-related outcomes in public school settings;

use objective measures to quantify sleep architecture and duration; and

examine the facilitators and barriers schools encounter when adopting a later school start time.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: KM was funded by a pre-doctoral fellowship from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease/NIH (T32-DK07718). NSR was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research/NIH (P20-NR014126).

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- NS

non-significant

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- S/R

self-report

- TST

total sleep time

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Statements:

Mr Minges conceptualized and designed the study, carried out the initial analyses, drafted the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Dr Redeker contributed to the conception of the study and interpretation of data, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- *1.Crowley SJ, Acebo C, Carskadon MA. Sleep, circadian rhythms, and delayed phase in adolescence. Sleep Med. 2007;8:602–12. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfson AR, Carskadon MA. Sleep schedules and daytime functioning in adolescents. Child Dev. 1998;69:875–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *3.Curcio G, Ferrara M, De Gennaro L. Sleep loss, learning capacity and academic performance. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:323–37. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matricciani LA, Olds TS, Blunden S, Rigney G, Williams MT. Never enough sleep: a brief history of sleep recommendations for children. Pediatrics. 2012;129:548–56. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Sleep Foundation. Teens and sleep. Washington, D.C: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Brien EM, Mindell JA. Sleep and risk-taking behavior in adolescents. Behav Sleep Med. 2005;3:113–33. doi: 10.1207/s15402010bsm0303_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noland H, Price JH, Dake J, Telljohann SK. Adolescents’ sleep behaviors and perceptions of sleep. J School Health. 2009;79:224–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carskadon MA, Wolfson AR, Acebo C, Tzischinsky O, Seifer R. Adolescent sleep patterns, circadian timing, and sleepiness at a transition to early school days. Sleep. 1998;21:871–81. doi: 10.1093/sleep/21.8.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagenauer MH, Perryman JI, Lee TM, Carskadon MA. Adolescent changes in the homeostatic and circadian regulation of sleep. Dev Neurosci. 2009;31:276–84. doi: 10.1159/000216538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carskadon MA, Acebo C, Jenni OG. Regulation of adolescent sleep: implications for behavior. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1021:276–91. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meier-Ewert HK, Ridker PM, Rifai N, Regan MM, Price NJ, Dinges DF, et al. Effect of sleep loss on C-reactive protein, an inflammatory marker of cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:678–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spiegel K, Knutson K, Leproult R, Tasali E, Cauter EV. Sleep loss: a novel risk factor for insulin resistance and Type 2 diabetes. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:2008–19. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00660.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taheri S, Lin L, Austin D, Young T, Mignot E. Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased body mass index. PLoS Med. 2004;1:e62. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0010062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knutson KL, Spiegel K, Penev P, Van Cauter E. The metabolic consequences of sleep deprivation. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11:163–78. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lowry R, Eaton DK, Foti K, McKnight-Eily L, Perry G, Galuska DA. Association of sleep duration with obesity among US high school students. J Obesity. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/476914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bass J, Turek FW. Sleepless in America: a pathway to obesity and the metabolic syndrome? Arch Int Med. 2005;165:15–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matthews KA, Dahl RE, Owens JF, Lee L, Hall M. Sleep duration and insulin resistance in healthy black and white adolescents. Sleep. 2012;35:1353–8. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKnight-Eily LR, Eaton DK, Lowry R, Croft JB, Presley-Cantrell L, Perry GS. Relationships between hours of sleep and health-risk behaviors in US adolescent students. Prev Med. 2011;53:271–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pasch KE, Laska MN, Lytle LA, Moe SG. Adolescent sleep, risk behaviors, and depressive symptoms: are they linked? Am J Health Behav. 2010;34:237. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.34.2.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu X. Sleep and adolescent suicidal behavior. Sleep. 2004;27:1351–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.7.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vorona RD, Szklo-Coxe M, Wu A, Dubik M, Zhao Y, Ware JC. Dissimilar teen crash rates in two neighboring southeastern virginia cities with different high school start times. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7:145–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaca F, Harris JS, Garrison HG, Vaca F, McKay MP. Drowsy driving. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45:433–4. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Milewski MD, Skaggs DL, Bishop GA, Pace JL, Ibrahim DA, Wren TA, et al. Chronic lack of sleep is associated with increased sports injuries in adolescent athletes. J Pediatr Orthop. 2014;34:129–33. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *24.Dewald JF, Meijer AM, Oort FJ, Kerkhof GA, Bögels SM. The influence of sleep quality, sleep duration and sleepiness on school performance in children and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:179–89. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drake C, Nickel C, Burduvali E, Roth T, Jefferson C, Badia P. The Pediatric Daytime Sleepiness Scale (PDSS): sleep habits and school outcomes in middle-school children. Sleep. 2003;26:455–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gibson ES, Powles A, Thabane L, O’Brien S, Molnar DS, Trajanovic N, et al. “Sleepiness” is serious in adolescence: two surveys of 3235 Canadian students. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Killgore WD, Kahn-Greene ET, Lipizzi EL, Newman RA, Kamimori GH, Balkin TJ. Sleep deprivation reduces perceived emotional intelligence and constructive thinking skills. Sleep Med. 2008;9:517–26. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kahn-Greene ET, Lipizzi EL, Conrad AK, Kamimori GH, Killgore WD. Sleep deprivation adversely affects interpersonal responses to frustration. Pers Indiv Differ. 2006;41:1433–43. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bates JE, Viken RJ, Alexander DB, Beyers J, Stockton L. Sleep and adjustment in preschool children: Sleep diary reports by mothers relate to behavior reports by teachers. Child Dev. 2002;73:62–75. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gregory AM, Sadeh A. Sleep, emotional and behavioral difficulties in children and adolescents. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16:129–36. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alfano CA, Zakem AH, Costa NM, Taylor LK, Weems CF. Sleep problems and their relation to cognitive factors, anxiety, and depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26:503–12. doi: 10.1002/da.20443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dexter D, Bijwadia J, Schilling D, Applebaugh G. Sleep, sleepiness and school start times: a preliminary study. Wisc Med J. 2003;102:44–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borlase BJ, Gander PH, Gibson RH. Effects of school start times and technology use on teenagers’ sleep: 1999–2008. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2013;11:46–54. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Epstein R, Chillag N, Lavie P. Starting times of school: effects on daytime functioning of fifth-grade children in Israel. Sleep. 1998;21:250–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/21.3.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perkinson-Gloor N, Lemola S, Grob A. Sleep duration, positive attitude toward life, and academic achievement: the role of daytime tiredness, behavioral persistence, and school start times. J Adol. 2013;36:311–8. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guerin N, Reinberg A, Testu F, Boulenguiez S, Mechkouri M, Touitou Y. Role of school schedule, age, and parental socioeconomic status on sleep duration and sleepiness of Parisian children. Chronobiol Int. 2001;18:1005–17. doi: 10.1081/cbi-100107974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolfson AR, Spaulding NL, Dandrow C, Baroni EM. Middle school start times: the importance of a good night’s sleep for young adolescents. Behav Sleep Med. 2007;5:194–209. doi: 10.1080/15402000701263809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carrell SE, Maghakian T, West JE. A’s from Zzzz’s? The causal effect of school start time on the academic achievement of adolescents. Am Econ J. 2011;3:62–81. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hinrichs P. When the bell tolls: the effects of school starting times on academic achievement. Educ Finance Policy. 2011;6:486–507. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edwards F. Early to rise? The effect of daily start times on academic performance. Econ Educ Rev. 2012;31:970–83. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoffman J. The New York Times. Vol. 2014. New York, NY: Mar 14, 2014. To keep teenagers alert, sleep in; p. A1. [Google Scholar]

- *42.American Academy of Pediatrics Adolescent Sleep Working Group. School Start Times for Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014 doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lamberg L. High schools find later start time helps students’ health and performance. J Am Med Assoc. 2009;301:2200–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yan B, Slagle M. School start time and academic achievement: a literature review. Blue Valley School District; Kentucky, USA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kirby M, Maggi S, D’Angiulli A. School start times and the sleep-wake cycle of adolescents: a review and critical evaluation of available evidence. Educ Researcher. 2011;40:56–61. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whittemore R, Chao A, Jang M, Minges KE, Park C. Methods for knowledge synthesis: An overview. Heart & lung. 2014;43:453–61. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *48.Vedaa O, Saxvig IW, Wilhelmsen-Langeland A, Bjorvatn B, Pallesen S. School start time, sleepiness and functioning in Norwegian adolescents. Scand J Educ Res. 2012;56:55–67. [Google Scholar]

- *49.Danner F, Phillips B. Adolescent sleep, school start times, and teen motor vehicle crashes. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:533–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *50.Li S, Arguelles L, Jiang F, Chen W, Jin X, Yan C, et al. Sleep, school performance, and a school-based intervention among school-aged children: a sleep series study in China. Plos One. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *51.Lufi D, Tzischinsky O, Hadar S. Delaying school starting time by one hour: Some effects on attention levels in adolescents. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7:137–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *52.Boergers J, Gable CJ, Owens JA. Later school start time is associated with improved sleep and daytime functioning in adolescents. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2014;35:11–7. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *53.Owens JA, Belon K, Moss P. Impact of delaying school start time on adolescent sleep, mood, and behavior. Arch Ped Adol Med. 2010;164:608–14. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wolfson AR, Carskadon MA. Understanding adolescents’ sleep patterns and school performance: a critical appraisal. Sleep Med Rev. 2003;7:491–506. doi: 10.1016/s1087-0792(03)90003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bergin C, Bergin D. Sleep: The E-ZZZ Intervention. Educ Leadership. 2009;67:44–7. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wrobel GD. The impact of school starting time on family life. Phi Delta Kappan. 1999;80:360–64. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Center for Applied Research and Educational Improvement. School start time study. [Accessed March 20, 2015];Final report summary. 1998 http://www.cehd.umn.edu/carei/Reports/summary.html.

- 58.Start School Later. [Accessed December 21, 2014];Success Stories. 2014 http://www.startschoollater.net/success-stories.html.

- 59.Egger M, Juni P, Bartlett C, Holenstein F, Sterne J. How important are comprehensive literature searches and the assessment of trial quality in systematic reviews?: Empirical study. Health Technol Assess. 2003;7:1–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: Literature search terms and strategy for OVID databases