Abstract

Introduction

Endovascular repair of traumatic thoracic aortic injuries (TTAI) is an alternative to conventional open surgical repair. Single institution studies have shown a survival benefit with TEVAR, but it is not clear if this is being realized nationally. The purpose of our study was to document trends in the increase in utilization of TEVAR and its impact on outcomes of TTAI nationally.

Methods

Patients admitted with a traumatic thoracic aortic injury between 2005 and 2011 were identified in the National Inpatient Sample (NIS). Patients were grouped by treatment into TEVAR, open repair, or nonoperative management groups. Primary outcomes were relative utilization over time and in-hospital mortality. Secondary outcomes included postoperative complications and length of stay. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to identify independent predictors of mortality.

Results

A total of 8384 patients were included, with 2492 (29.7%) undergoing TEVAR, 848 (10.1%) open repair, and 5044 (60.2%) managed nonoperatively. TEVAR has become the dominant treatment option for TTAI over the study period, starting at 6.5% of interventions in 2005 and accounting for 86.5% of interventions in 2011 (P<.001). Nonoperative management declined concurrently with the widespread of adoption TEVAR (79.8% to 53.7%, P<.001). In-hospital mortality following TEVAR decreased over the study period (33.3% in 2005 to 4.9% in 2011, P<.001), while an increase in mortality was observed for open repair (13.9% to 19.2%, P<.001). Procedural mortality (either TEVAR or open repair) decreased from 14.9% to 6.7% (P<.001), and mortality following any TTAI admission declined from 24.5% to 13.3% over the study period (P<.001). In addition to lower mortality, TEVAR was followed by fewer cardiac complications (4.1% vs. 8.5%), P<.001), respiratory complications (47.5% vs. 54.8%, P<.001), and shorter length of stay (18.4 vs. 20.2 days, P=.012) compared to open repair. In adjusted mortality analyses, open repair proved to be associated with twice the mortality risk compared to TEVAR (OR: 2.1, 95% CI: 1.6 – 2.7), while nonoperative management was associated with more than a four-fold increase in mortality (OR: 4.5, 95% CI: 3.8 – 5.3).

Conclusions

TEVAR is now the dominant surgical approach in TTAI with substantial perioperative morbidity and mortality benefits over open aortic repair. Overall mortality following admission for TTAI has declined, which is most likely the result of both the replacement of open repair by TEVAR, as well as the broadened eligibility for operative repair.

Introduction

Traumatic thoracic aortic injuries (TTAI) remain associated with high morbidity and mortality.1 Though highly lethal, TTAI has a relatively low incidence within the general population and as such, prior studies were largely limited to single-institution retrospective series. Various studies have suggested an in-hospital mortality of 15% to 30%, beginning with Parmley’s 1958 study.2, 3 Early studies assessing perioperative outcome following open repair showed poor results, with both high surgical mortality and morbidity, of which a high paraplegia rate was most notable.4

In 1997, Kato et al. were the first to report on endovascular stent grafting for TTAI.5 Studies conducted in the following years, which were mostly institutional-based, suggested a substantial reduction in morbidity and mortality associated with TEVAR, compared to open repair and nonoperative treatment.6-11 The Society for Vascular Surgery determined that endovascular repair of TTAI remained a key area requiring clinical guidelines to aid surgeons, referring physicians, and patients in the process of decision-making. In an effort to provide guidance for clinical practice, a selected panel of experts was tasked with conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis of the existing literature.12 Although various recommendations were provided, the panel concluded that the available evidence was of very low quality and that further evaluation of operative management of TTAI was warranted.

Hong et al. were the first to utilize a national database to characterize trends in treatment of TTAI and could not confirm the perioperative mortality benefit associated with TEVAR on a national level.13 Their 2001-2007 Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) data are biased, yielding only 14 TEVAR ICD-9 codes prior to 2006 which underreport its use, as ICD-9 coding did not differentiate a TEVAR from an open repair until October 2005.

Since it remains unclear whether these favorable outcomes demonstrated in institutional series are being realized nationally and the use of endovascular treatment modalities continues to increase, the purpose of our study was to provide a contemporaneous update to the study by Hong et al. using specific TEVAR coding and further assess the relative effectiveness and trends in the use of endovascular repair for traumatic thoracic aortic injury, as well as overall outcome following TTAI admission.

Methods

Database

For this study, we utilized the NIS. The NIS is the largest US all-payer inpatient database, with over 8 million documented annual hospitalizations. The NIS is maintained by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ) as part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project.14 The NIS represents 20% of all annual U.S. hospitalizations. Through the use of hospital sampling weights, actual annual U.S. hospitalization volumes are approximated. These weighted estimates are utilized throughout this analysis, as recommended by the AHRQ. The database contains de-identified data only without any protected health information. Therefore, Institutional Review Board approval and patient consent were waived.

Patients

Patients were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9). All patients with a diagnosis code for traumatic aortic injury (901.0) between 2005 and 2011 were included. Identified TTAI patients were subsequently grouped by treatment received (TEVAR, open repair, or nonoperative management). Corresponding ICD-9 procedural codes and descriptions were: endovascular graft implantation to the thoracic aorta (39.73), open thoracic vessel replacement (38.45), or nonoperative management when neither of the procedure codes was mentioned.

Documented patient characteristics included demographics (age, sex, race), comorbid conditions (coronary artery disease, diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic kidney disease, and cerebrovascular disease) and concomitant injuries (brain, hemothorax, cardiac, pulmonary, liver, spleen, kidney, pelvic organs, gastro-intestinal, skull fracture, vertebral fracture, and major orthopedic fracture). Brain injury was defined as loss of consciousness lasting longer than 24 hours, brain laceration or contusion, or intracerebral hemorrhage. Cardiac and pulmonary injury included both contusion and laceration. A major orthopedic fracture was defined as a fracture of the spine, pelvis, or femur. Interventions to treat concurrent injuries were grouped into intracranial, thoracic, and abdominal procedures. These interventions did not include diagnostic procedures, and were only considered for patients with a reported traumatic injury in the corresponding organ. Hospital characteristics included hospital setting (rural, urban non-teaching, urban teaching) and hospital bedsize (small medium large). A hospital’s bedsize category is nested within location and teaching status. Small hospital bedsize is defined as 1-49, 50-99 and 1-299 beds, respectively for rural, urban non-teaching and urban teaching hospitals, medium bedsize as 50-99, 100-199, 300-499, respectively, and 100+, 200+, and 500+ beds is considered a large bedsize hospital, respectively. Adverse in-hospital outcomes included death, cardiac or respiratory complications, paraplegia, stroke, acute renal failure, wound dehiscence, infection, discharge to home, and length of stay. Cardiac complications include postoperative myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest, cardiogenic shock, and ventricular fibrillation (Supplemental Table I). A respiratory complication was defined as a postoperative pneumonia, pulmonary insufficiency after trauma or surgery, transfusion-related acute lung injury, or acute respiratory failure. For paraplegia as a postoperative adverse outcome, patients admitted with vertebral fractures with spinal cord injury were not included. National cause-specific age-adjusted death rates due to traumatic aortic injuries (ICD-10 code: S25.0) were also obtained from Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER), an epidemiological internet based database maintained by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).15 More information on WONDER can be found on http://wonder.cdc.gov/.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages and continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation. Trends over time were assessed using the Cochran-Armitage test for trend. Differences were determined using χ2 and Fisher’s exact testing for categorical variables, and Student’s t-test and Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables, where appropriate. These analyses included an overall test of the three treatment groups, as well as a separate analysis comparing TEVAR and open repair patients only. In order to identify risk factors for mortality, all variables were first univariately tested using logistic regression analysis. Predictors with a p-value ≤ .1 were subsequently entered into a multivariable model to identify independent risk factors for mortality. Due to the limited number of diagnoses that can be provided per patient in this dataset, less life-threatening comorbid conditions and concomitant injuries are underreported in more complex cases. Since these conditions act as confounders for less severe cases, we chose not to include comorbidities and injuries with protective risk estimates. All tests were two-sided and significance was considered when p-value <0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS Statistics 21 (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

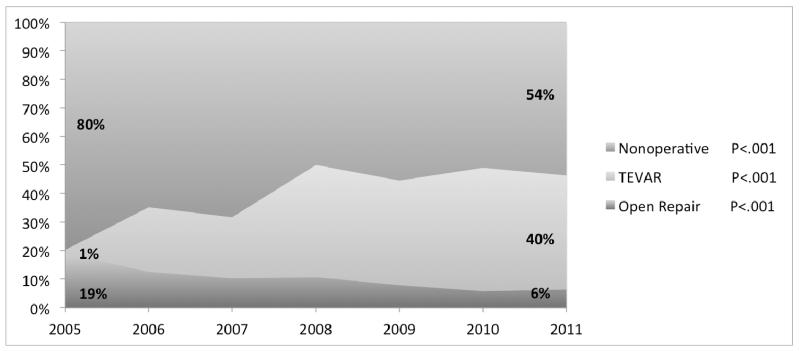

A total of 8384 patients were included, with 2492 (30%) undergoing TEVAR, 848 (10%) open repair, and 5044 (60%) undergoing no operative treatment for TTAI. Over the study period, the utilization of TEVAR increased from 6.5% of the operative volume in 2005 to 87% in 2011 (P<.001, Figure 1). Concurrently, the proportion of interventions performed with open repair decreased from 94% to 14% (P<.001), while the number of patients managed nonoperatively declined from 80% to 54% (P<.001).

Figure I.

Annual proportions of the various treatment strategies for the treatment of TTAI

Baseline and hospital characteristics

Baseline characteristics are detailed in Table I. TEVAR patients were generally older than those undergoing open repair (42.2 vs. 38.4 years, respectively, P<.001). Additionally, the TEVAR group included more non-white patients (33% vs. 28%, P=.030). TEVAR patients more commonly had coronary artery disease (3.0% vs. 1.3%, P=.007), diabetes (4.9% vs. 0.6% P<.001), hypertension (20% vs. 16%, P=.004), and cerebrovascular disease (P=5.3% vs. 2.9%, P=.005) compared to those undergoing open repair. Regarding hospital characteristics, TEVAR was more likely to be performed in urban teaching hospitals (91% vs. 85%, P<.001), while open repair was more likely performed in large bedsize centers (79% vs. 91%, P<.001). As TEVAR became more widely utilized, the proportion of patients undergoing TEVAR in small or medium bedsize hospitals increased (0% in 2005 to 28% in 2011, P<.001). For open repair, however, no changes in hospital bedsize were observed over time (7% to 8%, P=.635). No difference existed in the proportion of patients transferred from other hospitals between patients undergoing TEVAR and open repair (18% vs. 19%, P=.456). However, TEVAR was less often performed on the day of admission (57% vs. 66%, P<.001).

Table I.

Baseline and hospital characteristics

| Procedure | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| TEVAR (N=2492) |

Open Repair (N=848) |

Nonoperative (N=5044) |

Overall | TEVAR vs. OR | |

| Demographics | |||||

|

| |||||

| Age – years (SD) | 42.2 (18.3) | 38.4 (18.2) | 44.6 (20.7) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Male gender – % | 75.2% | 72.5% | 71.2% | .001 | .117 |

| Non-white race – % | 32.8% | 28.1% | 32.4% | .080 | .030 |

|

| |||||

| Comorbidities | |||||

|

| |||||

| Coronary disease – % | 3.0% | 1.3% | 6.5% | <.001 | .007 |

| Diabetes – % | 4.9% | 0.6% | 5.3% | <.001 | <.001 |

| Hypertension – % | 20.2% | 15.8% | 19.5% | .016 | .004 |

| Heart Failure – % | 1.0% | 1.1% | 4.2% | <.001 | .803 |

| COPD – % | 3.0% | 3.4% | 3.3% | .726 | .553 |

| Chronic kidney disease – % | 1.2% | 1.1% | 1.3% | .765 | .809 |

| Cerebrovasc disease – % | 5.3% | 2.9% | 2.2% | <.001 | .005 |

|

| |||||

| Hospital Characteristics | |||||

|

| |||||

| Hospital Setting – % | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| Rural | 2.4% | 1.2% | 2.8% | ||

| Urban non-teaching | 6.2% | 13.9% | 14.2% | ||

| Urban teaching | 91.4% | 85.0% | 83.0% | ||

| Hospital Bedsize – % | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| Small | 2.6% | 0.5% | 2.3% | ||

| Medium | 18.1% | 8.2% | 19.6% | ||

| Large | 79.3% | 91.4% | 78.1% | ||

|

| |||||

| Transf. from other hospital | 17.5% | 18.6% | 12.3% | <.001 | .456 |

| Emergency admission | 91.8% | 91.1% | 93.5% | .004 | .550 |

| Surgery on day of admissionα – % | 57.0% | 65.6% | - | - | <.001 |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

among emergent admissions only (10% missing cases)

Concomitant injuries and interventions

Concomitant injuries were more pronounced in TEVAR patients as compared to open repair patients (Table II). Brain injuries were diagnosed concomitantly in 26% of TEVAR patients vs. 17% of open repair patients (P<.001). Similarly, the TEVAR group more commonly had cardiac injuries (3.9% vs. 1.1%, P<.001), pulmonary injuries (32% vs. 22%, P<.001), and spleen juries (25% vs. 21%, P=.007). Also, patients undergoing TEVAR more frequently suffered a skull fracture (19% vs. 15%, P=.017), and vertebral fractures without spinal cord injury (35% vs. 29%, P=.002). Regarding the treatment of concurrent injuries, TEVAR patients more often underwent intracranial interventions (4.8% vs. 2.5%, P<.001), while no difference was observed in the frequency of thoracic (16.9% vs. 18.9%, P=.405), and abdominal interventions (13.7% vs. 13.5%, P=.991).

Table II.

Concomitant injuries and interventions

| Procedure | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| TEVAR (N=2492) |

Open Repair (N=848) |

Nonoperative (N=5044) |

Overall | TEVAR vs. OR | |

| Number of injuries – median (IQR) |

3 (1-4) | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-3) | <.001 | <.001 |

|

| |||||

| Brain – % | 26.2% | 17.2% | 24.4% | <.001 | <.001 |

|

| |||||

| Thoracic | |||||

|

| |||||

| Hemothorax – % | 11.2% | 11.8% | 10.4% | .341 | .659 |

| Cardiac – % | 3.9% | 1.1% | 3.8% | <.001 | <.001 |

| Pulmonary – % | 31.6% | 22.4% | 24.6% | <.001 | <.001 |

|

| |||||

| Abdominal | |||||

|

| |||||

| Liver – % | 24.1% | 21.3% | 21.4% | .028 | .104 |

| Spleen – % | 25.4% | 20.9% | 22.3% | .003 | .007 |

| Kidney – % | 13.5% | 12.0% | 9.6% | <.001 | .278 |

| Pelvic organs – % | 3.1% | 2.2% | 2.6% | .284 | .201 |

| GI-tract – % | 9.7% | 9.5% | 8.9% | .482 | .912 |

|

| |||||

| Fractures | |||||

|

| |||||

| Skull fracture – % | 18.7% | 15.1% | 14.2% | <.001 | .017 |

| Vertebral fracture – % | 37.4% | 32.1% | 31.2% | <.001 | .005 |

| Spinal involv – % | 3.7% | 3.4% | 4.9% | .023 | .671 |

| No spinal involv – % | 34.7% | 28.7% | 27.6% | <.001 | .002 |

| Major orthopedic – % | 57.9% | 56.8% | 48.0% | <.001 | .587 |

|

| |||||

| Interventions | |||||

|

| |||||

| Intracranial – % | 4.8% | 2.5% | 2.6% | <.001 | .003 |

| Thoracic – % | 16.9% | 18.9% | 17.2% | .405 | .190 |

| Abdominal – % | 13.7% | 13.5% | 13.7% | .991 | .954 |

Perioperative outcomes

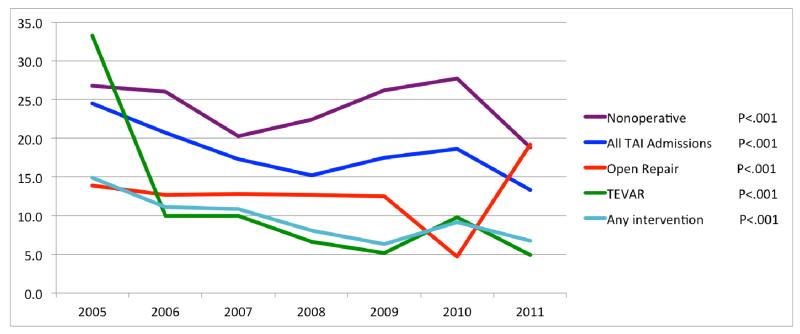

With an average of 7.8% over the study period, death following TEVAR was considerably lower compared to open repair (13%, P<.001, Table III), and nonoperative management (24% P<.001). This mortality difference held when comparing TEVAR versus open repair for procedures performed on day of admission (8.5% vs. 13%, P=.003). Over time, in-hospital mortality after TEVAR decreased from 33% in 2005 to 4.9% in 2011 (P<.001, Figure II). Death among patients who underwent open repair remained stable at first, but as the proportion of patients undergoing open repair further declined, mortality increased (14% to 19%, P<.001). Concurrently with the widespread adoption of TEVAR, death following any intervention (i.e. either TEVAR or open repair) decreased from 15% to 6.7% (P<.001). Nonoperative management remained associated with the highest mortality with a general trend towards lower mortality, although there was random variation over time (27% to 19%, P<.001). Overall mortality following admission for TTAI decreased from 25% to 13% (P<.001). A similar decrease in death due to TTAI was seen in national CDC data, with mortality declining from 5 to 3 per 10,000 (40%) between 2000 and 2011 with a continuing downward trend in more recent years.15 In addition to lower mortality, TEVAR was associated with fewer cardiac complications (4.1% vs. 8.5%, P<.001), and respiratory complications (48% vs. 55%, P<.001) compared to open repair. Furthermore, TEVAR was associated with a shorter length of stay (18.4 vs. 20.2 days, P=.012). Hospital charges, however, were significantly higher for TEVAR compared to open repair ($238,392 vs. $182,403, P<.001). No differences were found in rates of paraplegia, stroke, acute renal failure, postoperative infection, and wound dehiscence (Table III).

Table III.

Postoperative outcomes

| Procedure | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| TEVAR (N=2492) |

Open Repair (N=848) |

Nonoperative (N=5044) |

Overall | TEVAR vs. OR | |

| Death – % | 7.8% | 12.7% | 24.2% | <.001 | <.001 |

| Death surgery on day 1 – % | 8.5% | 13.4% | - | - | .003 |

|

| |||||

| Cardiac complication – % | 4.1% | 8.5% | 13.0% | <.001 | <.001 |

| Paraplegia α – % | 0.8% | 0.5% | 0.6% | .428 | .480 |

| Stroke complication – % | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.5% | .711 | .867 |

| Acute renal failure – % | 9.7% | 10.0% | 10.5% | .584 | .791 |

| Respiratory – % | 47.5% | 54.8% | 38.3% | <.001 | <.001 |

| Wound Dehiscence – % | 1.2% | 1.2% | 0.9% | .357 | .974 |

| Postoperative infection – % | 1.8% | 2.8% | 1.8% | .117 | .070 |

|

| |||||

| Length of stay – days (SD) | 18.4 (18.6) | 20.2 (18.1) | 14.8 (18.8) | <.001 | .012 |

| Discharge to home – % | 64.0% | 65.8% | 68.5% | <.001 | .336 |

| Total hospital charges – $ | 279,828 | 238,392 | 182,403 | <.001 | <.001 |

excluding patients admitted with spinal involved vertebral fractures

Figure II.

Changes in in-hospital mortality over time stratified by treatment strategy

Independent predictors of mortality

Predictors of mortality are listed in Table IV. In adjusted analyses, open repair had twice the mortality risk compared to TEVAR (OR: 2.1, 95% CI: 1.6 – 2.7), while nonoperative management was associated with a four fold higher mortality (OR: 4.5, 95% CI: 3.8 – 5.3). Other risk factors for mortality included age (OR: 1.1 per 10 years of age, 95% CI: 1.1 – 1.2), male gender (OR: 1.3, 95% CI: 1.1 – 1.5), and cerebrovascular disease (OR: 2.4, 95% CI: 1.8 – 3.2). Surgery on day of admission was also associated with higher mortality risks (OR: 1.6, 95% CI: 1.2 – 2.2). Concomitant injuries predictive of mortality included brain injury (OR: 1.4, 95% CI: 1.2 – 1.6), hemothorax (OR: 1.6, 95% CI: 1.3 – 1.9), cardiac injury (OR: 1.5, 95% CI: 1.1 – 2.0), and major orthopedic injury (OR: 1.3, 95% CI: 1.1 – 1.5). In addition, intracranial (OR: 3.0, 95% CI: 2.2 – 4.0), thoracic (OR: 1.9, 95% CI: 1.6 – 2.2), and abdominal interventions (OR: 2.1, 95% CI: 1.8 – 2.5) were established as risk factors for mortality.

Table IV.

Multivariable predictors of mortality after thoracic aortic injury

| Management | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|

| |||

| TEVAR | Reference | - | - |

| Open Repair | 2.1 | 1.6 – 2.7 | <.001 |

| Nonoperative | 4.5 | 3.8 – 5.3 | <.001 |

|

| |||

| Baseline Characteristics | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|

| |||

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.1 | 1.1 – 1.2 | <.001 |

| Male gender | 1.3 | 1.1 – 1.5 | .001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.2 | 0.9 – 1.6 | .299 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 2.4 | 1.8 – 3.2 | <.001 |

|

| |||

| Concomitant injuries | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|

| |||

| Brain injury | 1.4 | 1.2 – 1.6 | <.001 |

| Hemothorax | 1.6 | 1.3 – 1.9 | <.001 |

| Cardiac injury | 1.5 | 1.1 – 2.0 | .006 |

| Major orthopedic injury | 1.3 | 1.1 – 1.5 | <.001 |

|

| |||

| Other interventions | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|

| |||

| Intracranial intervention | 3.0 | 2.2 – 4.0 | <.001 |

| Thoracic intervention | 1.9 | 1.6 – 2.2 | <.001 |

| Abdominal intervention | 2.1 | 1.8 – 2.5 | <.001 |

|

| |||

| Timing | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|

| |||

| Surgery on day of admission | 1.6 | 1.2 – 2.2 | .002 |

We were unable to differentiate between emergent admissions and relatively stable patients (e.g., transferred and readmitted patients). However, sensitivity analyses were performed among all patients coded as non-elective (93% of the total cohort), and no notable differences were observed compared to the multivariable model for the cohort as a whole.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that TEVAR is now the dominant treatment modality for TTAI, with open repair only rarely being performed in recent years. Since the proportion of patients managed nonoperatively decreased by 26% (80% to 54%), our study indicates that TEVAR may have broadened patient eligibility for surgical repair, which has been suggested previously.13 This is also supported by the observation that TEVAR patients had more pre-operative comorbidities and concomitant injuries compared to patients undergoing open repair. Despite their worse condition at admission, this study demonstrates that in-hospital mortality and postoperative morbidity of patients selected for TEVAR are substantially lower compared to open repair. Due to the shift from open repair towards TEVAR, overall procedural mortality has declined, which was confirmed with national CDC data. In addition, as TEVAR became more widely used and the proportion of patients managed nonoperatively decreased, total mortality following admission for TTAI declined as well.

The first comprehensive study on TTAI was carried out in 1958, which defined the pathological mechanisms, histopathology, and epidemiologic characteristics of the untreated TTAI and was the first to propose management strategies for this highly lethal injury.2 Subsequently, open repair became the standard of care. In 1997, a large prospective multicenter trial conducted by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) reported that the operative mortality after open repair was 31%, with paraplegia occurring in 9% of patients.3 These rates are substantially higher than those for open repair in the present study where mortality was 12.7% and paraplegia was 0.8%. In that same year, endovascular stent-graft placement for TTAI was first described.5 The comparative literature of open repair vs. TEVAR has largely been at the institutional level. These studies consistently determined that TEVAR was associated with substantial decreases in perioperative morbidity and mortality compared to open repair.7-9, 11, 16-19 A second AAST analysis was published in 2008, in which 65% of patients were treated using endovascular repair.20 With an operative mortality of 7.2% and an incidence of paraplegia lower than 1%, perioperative outcomes following TEVAR were comparable to our study. In line with the institutional series, this AAST follow-up study found favorable perioperative results for TEVAR.20 Yet, Hong et al. could not confirm the perioperative mortality benefits associated with TEVAR on a national level utilizing the NIS for the years 2001 to 2007.13 The conflicting results between these data and the present study may be explained by lower patient numbers in the Hong et al. study, as well as confounding resulting from the inclusion of data from 2001-2005, prior to the introduction of a specific ICD-9 procedure code for TEVAR. In addition, mortality trend analysis showed a dramatic decrease in perioperative mortality for TEVAR in the later years of our analysis, during which more TEVARs were performed as a proportion of total interventions. This could represent a learning curve for both surgeons and hospitals,21-23 and may also explain why the earlier NIS study did not find such a difference between TEVAR and open repair. Similar to the present study, de Mestral et al. showed a rapid increase in the utilization of endovascular repair for TTAI using the Canadian National Trauma Registry.24 Interestingly, they reported a concurrent increase in nonoperative treatment that was associated with a decline in mortality. As a result, de Mestral et al. recommended that nonoperative treatment for TTAI should be a major focus in the endovascular era. In our study, however, the proportion of patients treated nonoperatively decreased, and the associated mortality remained substantially higher compared to TEVAR over the entire length of the study. Further data are needed comparing outcomes of patients undergoing TEVAR and those treated nonoperatively stratified by grade of the aortic injury.

An unadjusted comparison of adverse postoperative events between TEVAR and open repair is complicated by the high diversity and prevalence of concomitant injuries. However, as length of stay was shorter, and the incidence of postoperative complications such as cardiac and respiratory complications was lower among TEVAR patients despite comorbidities and concomitant injuries being more pronounced, this further supports the benefits of TEVAR over open repair in the perioperative period. Earlier series showed high rates of paraplegia following open repair.3 Our results demonstrated similar low occurrence rates for paraplegia, as well as acute renal failure, for open repair and TEVAR, which is in line with more recent studies.16, 20 Shorter length of stay after TEVAR has also been reported previously.8, 18

In regards to the clinical practice guideline from the SVS selected expert committee, our results confirm the recommendation that TEVAR should be preferentially performed over open surgical repair and nonoperative management.12 The use of TEVAR is further supported by recent studies demonstrating good long-term results of endovascular repair for TTAI.25-27 The expert panel additionally advised that aortic repair should be performed within 24 hours after admission barring other serious concomitant nonaortic injuries. However, our results showed that surgery on the day of admission was an independent risk factor for in-hospital mortality. Since this increased risk may very well be driven by patients with relatively severe aortic injuries requiring more urgent treatment, we believe that these data should not be used for deriving recommendations in regards to the timing of surgery.

TEVAR was more commonly performed in urban teaching hospitals. This was anticipated, as novel techniques and technologies such as TEVAR are typically introduced first to high volume academic centers. Also, the majority of these patients were likely transferred or brought directly to Level 1 trauma centers, which are predominantly urban and teaching. Prior literature evaluating differences in hospital costs between TEVAR and open repair is conflicting. While a study from Canada found comparable procedural costs between TEVAR and open repair,28 a recent study conducted in Houston found higher hospital charges for patients who underwent TEVAR.16 Although procedural costs are not documented in the database that was used, the NIS does provide total hospital charges for the hospitalization. In line with the more recent study, we found that TEVAR was associated with higher total charges. However, treatment of concomitant injuries, which were more pronounced among TEVAR patients, may have contributed to this cost difference.

This study has several limitations that should be considered. First, as with every ICD-9 based database, the NIS lacks clinically relevant data such as the grade of the aortic injury, and hemodynamic status at admission. This lack of specificity should be kept in mind when comparing outcome differences between treatment strategies, as confounding by indication may influence results. The lack of these data may have resulted in heterogeneity particularly in the nonoperative treatment group, as we were unable to differentiate between patients who were turned down for surgery due to the severity of the aortic injury or because of prohibitive surgical risks resulting from comorbidities. Additionally, the nonoperative treatment group may have included patients that did not undergo aortic repair because the low grade of the aortic injury did not warrant repair or because concomitant injuries required more immediate medical attention. In addition, previous studies have indicated that results on surgical complications from administrative databases should be interpreted with caution, since these data resources have problems in regards to documentation of non-fatal perioperative outcomes.29-31 Furthermore, due to the limited number of diagnoses that can be reported per case, common comorbidities and less threatening concomitant injuries are underreported in more complex patients. As a result, these conditions act as confounders for less severe cases, resulting in protective risk estimates in regression analyses. As these estimates did not accurately reflect the association with mortality, we decided to exclude these variables from further analyses. Also, we were unable to differentiate between emergent admissions, and those (re)admitted for their procedure. However, sensitivity analyses among all patients coded as non-elective showed no notable differences in the multivariable model. Finally, we could not distinguish between blunt and penetrating thoracic aortic injuries using ICD-9 coding. However, since the majority of chest traumas are of blunt nature,32 we presume our cohort to predominantly consist of blunt TTAI patients. Also, the observed high prevalence of orthopedic injuries is often observed in blunt trauma patients, and is in line with prior studies reporting on blunt TTAI.3

In conclusion, traumatic thoracic aortic injury continues to be a highly lethal injury. TEVAR is now the dominant surgical approach in TTAI with substantial perioperative morbidity and mortality benefits over open aortic repair. Overall mortality following admission for TTAI has declined, which is most likely the result of both the replacement of open repair by TEVAR, as well as the broadened eligibility for operative repair.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grant 5R01HL105453-03 from the NHLBI and the NIH T32 Harvard-Longwood Research Training in Vascular Surgery grant HL007734.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Clancy TV, Gary Maxwell J, Covington DL, Brinker CC, Blackman D. A statewide analysis of level I and II trauma centers for patients with major injuries. J Trauma. 2001;51(2):346–51. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200108000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parmley LF, Mattingly TW, Manion WC, Jahnke EJ., Jr Nonpenetrating traumatic injury of the aorta. Circulation. 1958;17(6):1086–101. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.17.6.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fabian TC, Richardson JD, Croce MA, Smith JS, Jr., Rodman G, Jr., Kearney PA, et al. Prospective study of blunt aortic injury: Multicenter Trial of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma. 1997;42(3):374–80. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199703000-00003. discussion 80-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cowley RA, Turney SZ, Hankins JR, Rodriguez A, Attar S, Shankar BS. Rupture of thoracic aorta caused by blunt trauma. A fifteen-year experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1990;100(5):652–60. discussion 60-1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kato N, Dake MD, Miller DC, Semba CP, Mitchell RS, Razavi MK, et al. Traumatic thoracic aortic aneurysm: treatment with endovascular stent-grafts. Radiology. 1997;205(3):657–62. doi: 10.1148/radiology.205.3.9393517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffer EK, Karmy-Jones R, Bloch RD, Meissner MH, Borsa JJ, Nicholls SC, et al. Treatment of acute thoracic aortic injury with commercially available abdominal aortic stent-grafts. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13(10):1037–41. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61870-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xenos ES, Abedi NN, Davenport DL, Minion DJ, Hamdallah O, Sorial EE, et al. Meta-analysis of endovascular vs open repair for traumatic descending thoracic aortic rupture. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48(5):1343–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang GL, Tehrani HY, Usman A, Katariya K, Otero C, Perez E, et al. Reduced mortality, paraplegia, and stroke with stent graft repair of blunt aortic transections: a modern meta-analysis. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47(3):671–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Estrera AL, Miller CC, 3rd, Guajardo-Salinas G, Coogan S, Charlton-Ouw K, Safi HJ, et al. Update on blunt thoracic aortic injury: fifteen-year single-institution experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145(3 Suppl):S154–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khoynezhad A, Azizzadeh A, Donayre CE, Matsumoto A, Velazquez O, White R, et al. Results of a multicenter, prospective trial of thoracic endovascular aortic repair for blunt thoracic aortic injury (RESCUE trial) J Vasc Surg. 2013;57(4):899–905. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.10.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinelli O, Malaj A, Gossetti B, Bertoletti G, Bresadola L, Irace L. Outcomes in the emergency endovascular repair of blunt thoracic aortic injuries. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58(3):832–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.02.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee WA, Matsumura JS, Mitchell RS, Farber MA, Greenberg RK, Azizzadeh A, et al. Endovascular repair of traumatic thoracic aortic injury: clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(1):187–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong MS, Feezor RJ, Lee WA, Nelson PR. The advent of thoracic endovascular aortic repair is associated with broadened treatment eligibility and decreased overall mortality in traumatic thoracic aortic injury. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(1):36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.08.009. discussion 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.HCUP HCUP NIS Database Documentation: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2015 updated August 2015; cited 2015 10/05/2015. Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/nisdbdocumentation.jsp.

- 15.National cause-specific age adjusted mortality data on the occurence of death due to thoracic aortic injury between 1999-2013 [Internet] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; cited 06/29/2015. Available from: http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.html. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azizzadeh A, Charlton-Ouw KM, Chen Z, Rahbar MH, Estrera AL, Amer H, et al. An outcome analysis of endovascular versus open repair of blunt traumatic aortic injuries. J Vasc Surg. 2013;57(1):108–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.05.110. discussion 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel HJ, Hemmila MR, Williams DM, Diener AC, Deeb GM. Late outcomes following open and endovascular repair of blunt thoracic aortic injury. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(3):615–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.09.058. discussion 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watson J, Slaiby J, Garcia Toca M, Marcaccio EJ, Jr., Chong TT. A 14-year experience with blunt thoracic aortic injury. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58(2):380–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell ME, Rushton FW, Jr., Boland AB, Byrd TC, Baldwin ZK. Emergency procedures on the descending thoracic aorta in the endovascular era. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54(5):1298–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.05.010. discussion 302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demetriades D, Velmahos GC, Scalea TM, Jurkovich GJ, Karmy-Jones R, Teixeira PG, et al. Operative repair or endovascular stent graft in blunt traumatic thoracic aortic injuries: results of an American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Multicenter Study. J Trauma. 2008;64(3):561–70. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181641bb3. discussion 70-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forbes TL, Chu MW, Lawlor DK, DeRose G, Harris KA. Learning curve analysis of thoracic endovascular aortic repair in relation to credentialing guidelines. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46(2):218–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holt PJ, Poloniecki JD, Gerrard D, Loftus IM, Thompson MM. Meta-analysis and systematic review of the relationship between volume and outcome in abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery. Br J Surg. 2007;94(4):395–403. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finks JF, Osborne NH, Birkmeyer JD. Trends in hospital volume and operative mortality for high-risk surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(22):2128–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1010705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Mestral C, Dueck A, Sharma SS, Haas B, Gomez D, Hsiao M, et al. Evolution of the incidence, management, and mortality of blunt thoracic aortic injury: a population-based analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216(6):1110–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Canaud L, Marty-Ane C, Ziza V, Branchereau P, Alric P. Minimum 10-year follow-up of endovascular repair for acute traumatic transection of the thoracic aorta. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;149(3):825–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.10.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steuer J, Bjorck M, Sonesson B, Resch T, Dias N, Hultgren R, et al. Editor’s Choice - Durability of Endovascular Repair in Blunt Traumatic Thoracic Aortic Injury: Long-Term Outcome from Four Tertiary Referral Centers. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;50(4):460–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kidane B, Plourde M, Chadi SA, Iansavitchene A, Meade MO, Parry NG, et al. The effect of loss to follow-up on treatment of blunt traumatic thoracic aortic injury. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61(6):1624–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung J, Owen R, Turnbull R, Chyczij H, Winkelaar G, Gibney N. Endovascular repair in traumatic thoracic aortic injuries: comparison with open surgical repair. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19(4):479–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawson EH, Louie R, Zingmond DS, Brook RH, Hall BL, Han L, et al. A comparison of clinical registry versus administrative claims data for reporting of 30-day surgical complications. Ann Surg. 2012;256(6):973–81. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826b4c4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bensley RP, Yoshida S, Lo RC, Fokkema M, Hamdan AD, Wyers MC, et al. Accuracy of administrative data versus clinical data to evaluate carotid endarterectomy and carotid stenting. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58(2):412–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fokkema M, Hurks R, Curran T, Bensley RP, Hamdan AD, Wyers MC, et al. The impact of the present on admission indicator on the accuracy of administrative data for carotid endarterectomy and stenting. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59(1):32–8. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LoCicero J, 3rd, Mattox KL. Epidemiology of chest trauma. Surg Clin North Am. 1989;69(1):15–9. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)44730-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.