Abstract

Objective

In a large sample of community-dwelling older adults with histories of exposure to a broad range of traumatic events, we examined the extent to which appraisals of traumatic events mediate the relations between insecure attachment styles and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptom severity.

Method

Participants completed an assessment of adult attachment, in addition to measures of PTSD symptom severity, event centrality, event severity, and ratings of the A1 PTSD diagnostic criterion for the potentially traumatic life event that bothered them most at the time of the study.

Results

Consistent with theoretical proposals and empirical studies indicating that individual differences in adult attachment systematically influence how individuals evaluate distressing events, individuals with higher attachment anxiety perceived their traumatic life events to be more central to their identity and more severe. Greater event centrality and event severity were each in turn related to higher PTSD symptom severity. In contrast, the relation between attachment avoidance and PTSD symptoms was not mediated by appraisals of event centrality or event severity. Furthermore, neither attachment anxiety nor attachment avoidance was related to participants’ ratings of the A1 PTSD diagnostic criterion.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that attachment anxiety contributes to greater PTSD symptom severity through heightened perceptions of traumatic events as central to identity and severe.

Keywords: attachment, posttraumatic stress, appraisals, event centrality

Maladaptive Trauma Appraisals Mediate the Relation Between Attachment Anxiety and PTSD Symptom Severity

Research concerning factors that explain why some individuals are vulnerable and others resistant to the detrimental effects of trauma exposure has shown that attachment style is an important predictor of the nature and severity of posttraumatic outcomes (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007; Mikulincer, Shaver, & Horesh, 2006). According to attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969/1982; Hazan & Shaver, 1987), an individual’s attachment style reflects their beliefs and expectations concerning the availability and responsiveness of significant others during times of need. Bowlby (1973) claimed that systematic patterns of attachment-related beliefs and behaviors initially develop in the context of relationships with early caregivers as individuals attempt to gain proximity to and support from attachment figures to alleviate distress. Over time these experiences form generalized cognitive representational models (i.e., internal working models) of the self and others in close relationships that guide the affect regulation strategies individuals rely on when potential or actual threats are perceived. Adult attachment theorists (e.g., Collins, 1996; Shaver & Mikulincer, 2002) further proposed that these early internal working models are activated during encounters with physical or emotional threats in adulthood and continue to influence how individuals appraise and cope with distressing events throughout the life course. Although previous research has provided strong evidence that attachment disruptions are associated with a heightened risk of negative posttraumatic outcomes (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2014), the specific processes through which individual differences in attachment style operate remain understudied. The purpose of the present research was to examine potential mechanisms through which attachment styles contribute to posttraumatic stress. Specifically, we examined the extent to which individual differences in insecure attachment lead to elevated PTSD symptom severity by influencing appraisals of traumatic life events.

Individual Differences in Attachment Style and Posttraumatic Stress

In addition to describing the adaptive regulatory functions of the attachment system, Bowlby’s theory of attachment (1988) delineates individual differences in relational patterns that reflect a person’s particular history of attachment experiences. Bowlby claimed that interactions with significant others who are consistently available and responsive during times of need promote the formation of secure attachment, which is characterized by a basic trust in the world and in the ability to regulate one’s own emotions. Positive beliefs and expectations about one’s personal competence and the intentions and good-will of others are thought to facilitate effective emotion regulation strategies that buffer psychological distress during encounters with external and internal stressors. Consistent with this theoretical proposal, empirical research indicates that adults with secure attachment styles maintain positive beliefs about distress management (Creasey, 2002; Mikulincer & Florian, 1995) and rely on more effective coping strategies (e.g., problem-focused coping, support seeking behaviors; Lussier, Sabourin, & Turgeon, 1997; Mikulincer & Florian, 1995), which promote psychological adjustment and well-being following exposure to trauma (Mikulincer et al.,1993; O’Connor & Elklit, 2008).

In contrast, interactions with significant others who are unavailable or unresponsive to bids for proximity and support are thought to disrupt the formation of attachment security and the development of internal resources needed to cope with real or imagined threats. Failure to attain attachment security leads to the development of an insecure attachment style, which is associated with reliance on maladaptive affect regulation strategies that contribute to emotional problems and psychopathology during times of stress. In particular, interactions with significant others who are inconsistently available and responsive are thought to promote the development of attachment anxiety, one dimension of insecure attachment characterized by continuous activation of the attachment system which results in persistent concerns about and desire for proximity to attachment figures combined with a lack of confidence that proximity will be attained. Attachment anxiety is associated with hyper-activating attachment strategies including heightened attention to threatening information (Mikulincer, Gillath, & Shaver, 2002), the intensification of emotional distress in response to stressful events (Collins, 1996; Maunder, Lancee, Nolan, Hunter, & Tannenbaum, 2006), rumination of threat-related concerns (Mikulincer & Florian, 1998), as well as heightened perceptions and appraisals of threat (Mikulincer & Florian, 1995; Pielage, Gerlsma, & Schaap, 2000). These hyper-activating strategies are thought to be adaptive in relationships in which the intensification of emotional distress increases the likelihood of attaining proximity to and comfort from attachment figures to alleviate stress. However, attachment anxiety in adulthood is associated with a wide range of negative outcomes including depression, anxiety, prolonged grief, and hostility (Fraley & Bonanno, 2004; Mikulincer et al., 1993; Wei, Russell, Mallinckrodt, & Vogel, 2007). For example, in a study of former prisoners of war (POWs), those with higher attachment anxiety described their experience of war captivity as more negative, and reported higher levels of suffering, feelings of abandonment, and impaired functioning compared to ex-POWs with a secure attachment style (Solomon et al., 1998).

The second dimension of insecure attachment, attachment avoidance, is characterized by efforts to inhibit or down-regulate activation of the attachment system to minimize perceived threats and distress (Mikulincer, Shaver, & Pereg, 2003). Attachment avoidance is thought to result from interactions with consistently unresponsive significant others with whom proximity seeking is determined to be a nonviable option to alleviate stress. Accordingly, attachment avoidance is thought to promote reliance on deactivating emotion regulation strategies, including motivated inattention to threatening information (Edelstein & Gillath, 2008), the suppression of thoughts that evoke distress (Fraley & Shaver, 1997), reduced accessibility to memories of negative and traumatic events (Edelstein et al., 2005; Mikulincer & Orbach, 1995), and a reduced capacity to report or acknowledge negative emotions (Collins, 1996) despite evidence of heightened physiological reactivity to stress (Maunder et al., 2006). Over time these deactivating emotion regulation strategies are thought to generalize to a wide variety of distressing situations including those without direct implications for interpersonal relationships.

Overall both hyper-activating and deactivating emotion regulation strategies constitute risk factors for poor coping and maladjustment following stressful and traumatic experiences in adulthood. A growing body of research has documented associations between insecure attachment and greater PTSD symptoms in studies of adult survivors of interpersonal trauma (e.g., Sandberg, 2010), high-exposure survivors of terrorism (Fraley et al., 2006), former POWs (e.g., Solomon et al., 2008), Holocaust survivors (Cohen, Dekel, & Solomon, 2002), and adults with histories of child maltreatment (e.g., Muller, Sicoli, & Lemieux, 2000). Although the majority of studies indicate that both attachment anxiety and avoidance are associated with greater posttraumatic stress, in some studies attachment avoidance failed to predict PTSD symptoms in multivariate analyses (e.g., Besser, Neria, & Haynes, 2009; Declercq & Willemsen, 2006). This divergence in the predictive utility of attachment anxiety compared to avoidance is consistent with empirical studies showing that attachment anxiety is associated with more negative interpretations of distressing events (Collins, 1996), greater emotional intensity in general and in response to negative experiences (Mikulincer et al., 2003; Mikulincer & Orbach, 1995; Searle & Meara, 1999), and more negative perceptions of physical and psychological symptoms (Watt, McWilliams, & Campbell, 2005).

Additional converging evidence for the hypothesis that attachment anxiety and avoidance differentially influence the extent to which individuals perceive negative and traumatic events to be stressful is drawn from the few existing studies that have sought to identify mechanisms underlying the relation between insecure attachment and posttraumatic stress. In a study of civilians who endured chronic exposure to rocket and mortar fire, Besser et al. (2009) found that individuals with higher attachment anxiety perceived the terrorist attacks to be more stressful, and that elevated levels of perceived stress were in turn associated with more severe PTSD symptoms. In contrast, no evidence was found for perceived stress to mediate the relation between attachment avoidance and PTSD symptoms. Similarly, in research with college students, insecure attachment styles characterized by higher attachment anxiety increased the susceptibility to appraise negative life events as more stressful, which in turn was related to greater psychiatric symptoms, including depression, anxiety, and somatic complaints (Pielage et al., 2000). In contrast, no evidence was found for perceived stress to mediate the relation between an insecure attachment style characterized by mental representations of others as rejecting and unavailable (akin to attachment avoidance) and psychiatric symptoms. Collectively these studies suggest that attachment anxiety and avoidance differentially influence individuals’ evaluations of their negative and traumatic life experiences, and that these differences in trauma appraisals in turn impact the development and maintenance of trauma-related psychopathology.

A separate line of research has also pointed to the importance of individuals’ appraisals of traumatic events in determining the severity of their posttraumatic outcomes. Numerous studies have shown that subjective appraisals of traumas, which include individuals’ assessments of their trauma-related thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (e.g., the extent to which they felt afraid or helpless during the event, the impact of the event on their lives) are more strongly related to posttraumatic stress compared to objective characteristics of traumatic events, such as whether or not the event was interpersonal in nature (e.g., Martin, Cromer, DePrince, & Freyd, 2013; Ogle, Rubin, Bertsen, & Siegler, 2013). One type of appraisal that has received substantial attention in the trauma literature is event centrality, or the extent to which a person perceives their trauma to be a central component of their identity. Aspects of event centrality include the degree to which a trauma represents a turning point in one’s life story, the influence of the trauma on judgements of future events, and how important the trauma has become to the person’s sense of self. Robust associations have been reported between event centrality and more severe PTSD symptoms in a wide range of participant populations and trauma types, including non-clinical samples of younger (Berntsen & Rubin, 2006) and older adults (Boals, Hayslip, Knowles, & Banks, 2012) with and without current diagnoses of PTSD (Rubin, Dennis, & Beckham, 2011), bereaved individuals (e.g., Boelen, 2009), and individuals who survived bomb attacks (Blix, Solberg, & Heir, 2013). Furthermore, event centrality has been shown to explain unique variance in PTSD symptoms compared to objective characteristics of traumas (i.e., age-at-trauma, Berntsen, Rubin, & Siegler, 2011); individual difference measures associated with PTSD, including neuroticism, social support, coping, and subjective happiness (Berntsen et al., 2011; Ogle, Rubin, & Siegler, 2014); and other types of trauma-related psychopathology including anxiety, depression, and dissociation (Berntsen & Rubin, 2006, 2007).

The present study sought to combine these two areas of research to test whether insecure attachment contributes to PTSD symptom severity by increasing perceptions of traumatic events as central to identity. The identification of posttraumatic processes that explain the relation between insecure attachment and PTSD may advance our understanding of the causal mechanisms involved in the development and maintenance of PTSD as well as inform therapeutic treatments for the disorder. Furthermore, although event centrality and adult attachment have each been well studied in relation to posttraumatic stress, neither has been included in meta-analyses of PTSD studies (Brewin, Andrews, & Valentine, 2000; Ozer, Best, Lipsey, & Weiss, 2003). On the basis of theoretical proposals and empirical research indicating that attachment anxiety and avoidance differentially influence how individuals evaluate negative and threatening experiences, we hypothesized that elevated levels of attachment anxiety would be related to higher event centrality, which in turn would be associated with more severe PTSD symptoms. In contrast, we predicted that individuals with higher attachment avoidance would be less likely to judge their trauma to be a central component of their identity as evidenced by a negative relation between attachment avoidance and event centrality.

In addition to event centrality, we tested two other types of trauma appraisals that have been studied extensively in the PTSD literature and that represent additional aspects of an individual’s perception of their traumatic life event. First, participants rated the severity of their trauma by assessing the degree of damage caused by the event to their current and future well-being. Results from a meta-analysis of risk factors for PTSD (Brewin et al., 2000) revealed that trauma severity is one of the strongest predictors of PTSD in studies of trauma-exposed adults (average effect size = .23, range = −.14–.76). Second, participants’ rated the life-threatening nature of their trauma, specifically whether the event involved actual or threatened death, serious injury, or threat to the physical integrity of oneself or others in accordance with the DSM-IV-TR A1 criterion for a PTSD diagnosis. Meta-analytic research has shown that individuals who perceive their lives to be in danger during a trauma exhibit higher rates of PTSD (average effect size = .26, range = .13–.49; Ozer et al., 2003). In combination with event centrality, these appraisals can be conceptualized as different components of how a person evaluates their traumatic life event: the importance of the trauma to their identity (event centrality), the extent of the negative consequences of the event (trauma severity), and the life-threatening nature of the trauma (self-reported A1 criterion). Consistent with our hypotheses for event centrality, we predicted that individuals with elevated levels of attachment anxiety would perceive their traumas to be more severe and life-threatening, and that these appraisals would in turn be associated with greater PTSD symptom severity. In contrast, neither event severity nor self-reported A1 ratings were expected to mediate the relation between attachment avoidance and PTSD symptoms.

Method

Participants

Data were drawn from the 13th wave of the University of North Carolina Alumni Heart Study (UNCAHS), an ongoing longitudinal study of students who entered the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill in 1964–1966 and their spouses (Siegler et al., 1992). Details concerning recruitment and participation rates of the UNCAHS are published elsewhere (Hooker, Hoppmann, & Siegler, 2010). The UNCAHS was originally designed to examine personality as a predictor of coronary heart disease (CHD). At wave 12 (2008–2010), the study was expanded to include measures of PTSD and lifetime trauma exposure to investigate the relations between CHD and PTSD in a non-clinical sample. A measure of adult attachment and a second measure of PTSD symptoms was added at wave 13. Our analyses included the 1,146 respondents who reported at least one potentially traumatic life event and completed measures of event centrality, adult attachment, self-rated severity, and PTSD symptom severity on the wave 13 paper-based survey (2011–2012). The final sample was 61% male and 99.21% Caucasian, with a mean age of 63.43 (SD = 2.80), and a mean annual household income of $70–99,999. Approximately 9% had less than a college degree, 19% earned bachelor’s degrees, 22% had bachelor’s degrees plus additional training, 27% earned master’s degrees, and 22% earned advanced degrees. Analyses comparing UNCAHS respondents in the analysis sample to wave 13 respondents who were excluded due to missing data indicated that the analysis sample was slightly younger, more educated, and included a greater proportion of females (ηp2s ≤ .01). No differences were found for annual household income or marital status.

Measures

PTSD symptom severity

The PTSD Check List-Stressor Specific Version (PCL-S; Weathers, Litz, Huska, & Keane, 1994) is a 17-item measure of PTSD symptom severity. Using 5-point scales (1 = not at all, 5 = extremely), respondents indicate the extent to which a specific event produced each of the B, C, and D DSM-IV-TR PTSD symptoms during the previous month. The PCL has strong psychometric properties (Cronbach’s α = .94; Blanchard, Jones-Alexander, Buckley, & Forneris, 1996) including high agreement with clinician-diagnosed PTSD (r = .93). Cronbach’s α for the total severity score in the current sample was .93.

Attachment

Attachment anxiety and avoidance were assessed using the 12-item short form of the Experiences in Close Relationships Inventory (ECR-S; Wei et al., 2007). Participants rated the extent to which each item describes their feelings in close relationships on a 7-point scale (1 = disagree strongly, 7 = agree strongly). High scores on the anxiety and avoidance subscales indicate higher levels of attachment anxiety and avoidance, respectively. The ECR-S has high test-retest reliability (rs ≥ .82) and high construct validity (Wei et al., 2007). Cronbach’s αs for the anxiety and avoidance subscales in the present study were .74 and .77, respectively.

Event centrality

The Centrality of Event Scale-Short Form (CES, Berntsen & Rubin, 2006) includes 7 items that assess the extent to which a trauma forms a central component of personal identity, a turning point in the life story, and a reference point for everyday inferences using 5-point scales (1 = totally disagree, 5 = totally agree). Cronbach’s α for the current sample was .90. Mean scores were analyzed.

Event severity

The Four Kinds of Damage Scale (Rubin & Feeling, 2013) assessed participants’ ratings of the severity of their traumas. On 7-point scales (1 = negligible, 7 = as much as any event I could imagine), participants rated the extent of physical damage the trauma caused to themselves or close others, the emotional toll of the trauma on themselves or close others, the impact of the trauma on their financial well-being, and the extent to which the trauma will impact their future. Ratings for these 4 items were summed to create a total score. The scale has been shown to correlate highly with other measures of event severity (rs = .88–.92; Rubin & Feeling, 2013). Cronbach’s α for the current sample was .63.

Self-rated A1 criterion

Participants reported the life-threatening nature of their trauma using the DSM-IV-TR A1 criterion for a diagnosis of PTSD. Participants answered the following question, “Did the event involve actual or threatened death, serious injury, or threat to the physical integrity of yourself or others?” using the response options of “yes” and “no.” Forty-seven participants were missing A1 criterion ratings.

Procedure

All waves of the UNCAHS were approved by the Duke University Medical Center’s IRB. Wave 13 was completed via mail. On the wave 13 questionnaire, participants were asked to describe three traumatic life events. The instructions for the first event were to describe an event that currently bothered them most and that involved actual or threatened death, serious injury, or threat to the physical integrity of themselves or others in accordance with the DSM-IV-TR A1 PTSD criterion. If no event met these criteria, participants were asked to describe a very negative or stressful event that closely matched the criteria. For the second and third events, participants were asked to describe events that bothered them at the time of the study or in the past without reference to the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria. For each event, participants reported how often the event occurred and selected a trauma category that best matched the event from the list of events in the Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire (Kubany et al., 2000). Participants then completed the CES, A1 criterion rating, Four Kinds of Damage Scale, and PCL for each event, followed by the ECR-S. Given that the instructions for the first event were designed to elicit participants’ currently most distressing and severe trauma according to DSM-IV-TR diagnostic standards, our analyses included ratings for participants’ first reported traumatic life event.

Data Analysis

A parallel multiple mediator model using a bias-corrected bootstrapping procedure (Preacher & Hayes, 2008) was tested to examine the extent to which maladaptive appraisals of traumatic events mediate the relations between the dimensions of insecure attachment and PTSD symptoms. To examine the unique effects of attachment anxiety and avoidance on PTSD symptoms, both dimensions of insecure attachment were tested in a single model. Parallel multiple mediator models simultaneously test the indirect effects of each mediator while accounting for the shared association between them. This procedure is recommended over other methods of testing indirect effects (e.g., Sobel test) when more than one mediator is predicted to influence the dependent variable because it increases the precision and parsimony of the model without assuming multivariate normality of the distribution of indirect effects (Hayes, 2013). Point estimates and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (CI) were generated using 10,000 bootstrap samples. Point estimates of indirect effects are significant when the CI does not include zero. Gender (0 = male, 1 = female), income, and marital status were entered as covariates.

Results

Participants reported a wide range of potentially traumatic events. Prevalence rates were highest for unexpected death of a loved one (29.93%), followed by life-threatening personal illness (13.96%), other life-threatening event (13.70%), life threatening or disabling accident or illness of a loved one (10.73%), natural disaster that badly injured self or killed someone (7.24%), accident that badly injured self or killed someone (5.67%), motor vehicle accident that badly injured self or killed someone (5.58%), warfare or combat (3.05%), non-live birth pregnancy (1.48%), death threat (1.48%), childhood sexual abuse (1.31%), and physical assault by a stranger (1.05%). Less than 1% of the sample reported each of the following events: experiencing or witnessing an armed robbery, witnessing assault or murder, adulthood sexual assault, physical assault by a partner, childhood physical abuse, witnessing childhood family violence, and being stalked. Five participants elected to not disclose the nature of their trauma.

Descriptive statistics and correlations between key variables are reported in Supplemental Table 1. PCL severity scores were positively related to attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, event centrality, and event severity (rs = .36, .20, .51, .50; ps < .001), but not self-reported A1 criterion ratings (r = .00). Differential patterns of associations also emerged between the two dimensions of insecure attachment and the three measures of trauma appraisals. Attachment anxiety was positively associated with event centrality and event severity scores (rs = .18, .15; ps < .001), but not with self-reported A1 criterion ratings (r = −.02). In contrast, the associations between attachment avoidance and event centrality, event severity, and the A1 criterion ratings were all non-significant (rs = .03, .04, −.04).

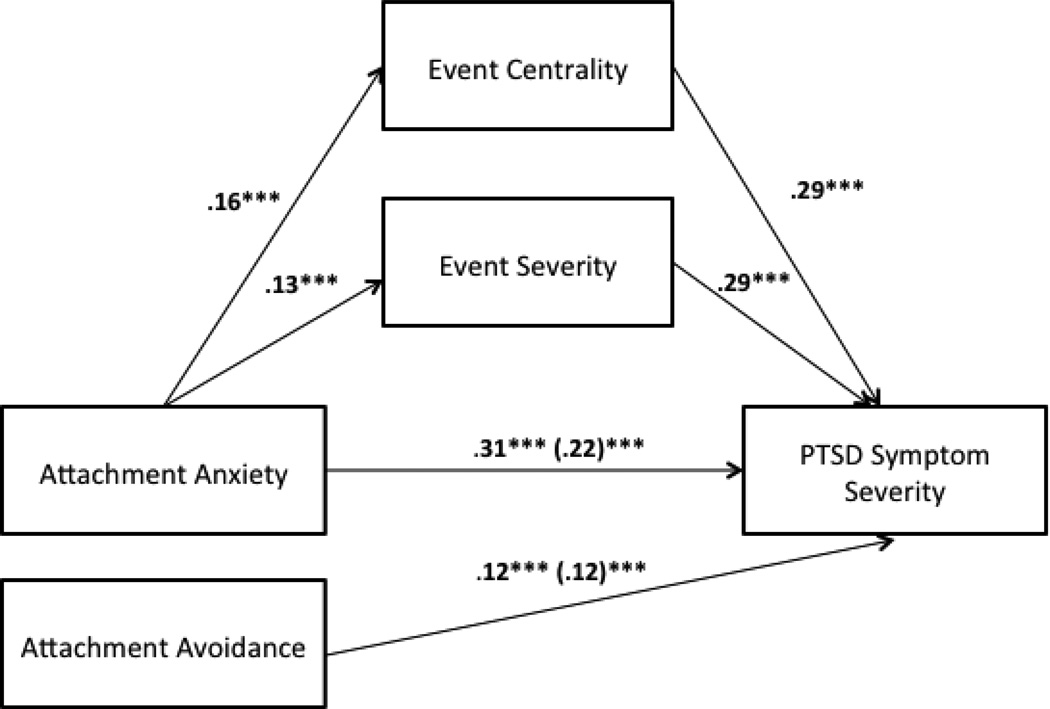

Next we examined whether insecure attachment leads to increases in PTSD symptom severity indirectly through maladaptive trauma appraisals. Because no significant associations emerged between either dimension of insecure attachment and the A1 criterion ratings, the A1 ratings were not included in the mediation model. Results indicated that event centrality and event severity scores each uniquely mediated the relation between attachment anxiety and PTSD symptom severity (Table 1). Standardized coefficients of significant paths are shown in Figure 1. Consistent with our hypothesis, participants with higher attachment anxiety rated their traumas as more central to their identity and more severe. These appraisals were in turn related to greater PTSD symptom severity. A pairwise comparison of the specific indirect effects revealed that event centrality and event severity each accounted for a statistically equivalent percentage of the indirect effect of attachment anxiety on PTSD symptom severity, coefficient = .10, SE = .12, CI [−.13, .33]. In contrast, no evidence was found for either event centrality or event severity to mediate the relation between attachment avoidance and PTSD symptoms. However, the model revealed significant direct effects for both attachment anxiety and avoidance on PTSD symptom severity, indicating that each dimension of insecure attachment explained unique variance in PTSD symptom severity independent of the indirect effects of attachment anxiety through event centrality and event severity (anxiety, b = 2.41, SE = .27, CI [1.89, 2.93]; avoidance, b = 1.31, SE = .26, CI [.80, 1.82]). The findings were unchanged when measures of trauma frequency and time since participants’ most distressing trauma were tested as covariates.

Table 1.

Indirect Effects of Attachment Anxiety and Avoidance on PTSD Symptom Severity Through Measures of Trauma Appraisals (n = 1,146)

| Attachment anxiety | Attachment avoidance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediators | Coefficient | SE | 95% BC CI | Coefficient | SE | 95% BC CI |

| Event centrality | .50 | .11 | [.30, .73] | −.01 | .09 | [−.20, .17] |

| Event severity | .40 | .11 | [.20, .62] | .01 | .09 | [−.18, .20] |

| Total indirect | .90 | .18 | [.55, 1.27] | .00 | .17 | [−.33, .32] |

Note. BC CI = bias-corrected confidence intervals. Full model, F(7, 1138) = 106.23, p < .001, R2 = .40.

Figure 1.

The direct and indirect effects of attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance on PTSD symptom severity through event centrality and event severity. Values represent the standardized coefficients of significant paths. Path coefficients in parentheses are the effects of attachment anxiety and avoidance on PTSD symptom severity independent of the proposed mediators.

Discussion

The present study examined the extent to which maladaptive appraisals of traumatic events mediate the relation between insecure attachment and PTSD symptom severity in a community-dwelling sample of older adults. Results showed that older adults with higher attachment anxiety rated their traumas as more central to their identity and more severe. Heightened perceptions of centrality and severity were in turn associated with more severe PTSD symptoms. A test of the equality of the indirect effects of attachment anxiety on PTSD symptom severity through event centrality and trauma severity showed that each mediator accounted for an equivalent percentage of the indirect effect. In contrast, no evidence was found for event centrality or event severity to mediate the relation between attachment avoidance and PTSD symptom severity. Although higher attachment avoidance scores predicted greater PTSD symptom severity, none of the effect was mediated by the trauma appraisals examined in the present study. Collectively, our findings suggest that attachment anxiety contributes to posttraumatic stress through maladaptive appraisals of traumatic events, in particular heightened perceptions of the trauma as central to one’s identity and as damaging to one’s current and future well-being.

Our finding that attachment anxiety but not attachment avoidance was associated with maladaptive trauma appraisals is consistent with prior research showing that insecure attachment orientations differentially influence individuals’ evaluations of stressful experiences. In particular, previous studies indicate that individuals with higher attachment anxiety appraise negative events as more distressing and threatening compared to individuals with secure attachment styles, whereas individuals with higher attachment avoidance evaluate emotional experiences as less negative and less emotionally intense (Collins, 1996; Mikulincer & Florian, 1995; Mikulincer & Orbach, 1995; Sutin & Gillath, 2009). Our findings extend this research by showing that attachment anxiety and avoidance also differentially influence how important individuals perceive their traumas to be to their personal identity and the extent of the negative impact of the trauma on their current and future well-being. Furthermore, our results add to the literature by showing that both dimensions of insecure attachment exerted unique effects on PTSD symptom severity. In contrast to studies in which the relation between attachment avoidance and PTSD symptoms attenuates to nonsignificant levels after accounting for the variance explained by anxiety, our results showed that attachment avoidance explained unique variance in PTSD symptoms over and above the direct effect of attachment anxiety and the indirect effects of attachment anxiety through event centrality and event severity. This finding suggests that individuals with elevated levels of both attachment anxiety and avoidance may be at a greater risk of developing PTSD symptoms compared to individuals with high scores on only one dimension of insecure attachment. Additional research is needed to further explore the processes through which attachment avoidance leads to greater PTSD symptom severity.

Our finding that individuals’ evaluations of their traumatic experiences influence PTSD symptom severity is also consistent with theoretical models of PTSD, in particular the autobiographical memory theory of PTSD, according to which the perceived centrality of a trauma memory to one’s identity and life story is among the primary mechanisms that promote the development and maintenance of PTSD symptoms (Rubin, Berntsen, et al., 2008; Rubin et al., 2011). The critical role of event centrality in the autobiographical memory theory of PTSD is based on extensive empirical work showing that event centrality is one of the most reliable predictors of PTSD symptom severity and other adverse posttraumatic outcomes, including depression (Berntsen & Rubin, 2006), poor physical health (Boals, 2010), and low self-esteem (Robinaugh & McNally, 2011). One question that has remained largely unaddressed in these studies is which factors explain why some individuals perceive their traumas to be central to their identity while other individuals do not. Previous studies have pointed to demographic variables (e.g., gender, age; Boals, 2010; Boals et al., 2012) and objective characteristics of traumatic events (Ogle et al., 2013) as potential explanatory mechanisms. Our findings suggest that individual differences in attachment may be one additional factor that explains the observed heterogeneity in the degree to which individuals construe their traumatic life events to be central components of their identity.

Our failure to find evidence that the relation between insecure attachment and PTSD symptom severity was mediated by ratings of the life-threatening nature of the traumas as indexed by self-reported A1 criterion ratings is consistent with a growing body of studies showing limited support for the utility of the A1 criterion in predicting PTSD symptoms. Although the inclusion of the A1 criterion in the DSM-IV-TR and its retention in the DSM-V is based on research suggesting that life-threatening events are associated with more severe PTSD symptoms than non-life-threatening traumas (Kilpatrick et al., 1998; Ozer et al., 2003), numerous studies have failed to find associations between A1 criterion ratings and PTSD symptom severity in bivariate and multivariate analyses (e.g., Lancaster, Melka, & Rodriquez, 2009; Ogle et al., 2014; Rubin & Feeling, 2013). Furthermore, other studies have shown that events that meet the A1 criterion often do not lead to PTSD (Breslau, David, Andreski, & Peterson, 1991; Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995), whereas events that fail to meet the A1 criterion can produce more severe PTSD symptoms than events that satisfy the A1 criterion (Dohrenwend, 2010; Gold, Marx, Soler-Baillo, & Sloan, 2005). Our results corroborate these studies in showing that individuals’ evaluations of the life-threatening nature of their traumatic experiences as indexed by the A1 criterion are not a reliable predictor of PTSD symptoms. In addition, our findings suggest that individual differences in attachment do not influence the likelihood that an individual will rate their trauma as life-threatening.

Several limitations of our study should be addressed in future research. First, our findings are subject to memory biases due to our reliance on retrospective and self-report data. Second, because the UNCAHS is comprised of participants who attended college in the 1960s, our sample is relatively advantaged with respect to socio-economic status. The lack of socio-ethnic diversity in the sample limits the generalizability of our findings. Replication in other diverse community and clinical samples is needed to advance our understanding of how insecure attachment contributes to the development and maintenance of PTSD symptoms. Third, the Cronbach’s α coefficient obtained for the Four Kinds of Damage Scale that assessed participants’ ratings of the severity of their traumas was relatively low. Replication with alternative measures of event severity is needed in future research. Fourth, the cross-sectional nature of the data analyzed in this report does not allow us to definitively test the causal direction of the relations between insecure attachment, trauma appraisals, and PTSD symptoms. The causal ordering examined in our analysis is well supported by attachment theory and related empirical research according to which attachment styles form early in life and subsequently develop into relatively stable trait-like individual differences that influence how people perceive and cope with stressful and threatening situations throughout the life course. However, longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether alternative causal relations are also empirically supported. Despite these limitations, the present study contributes to our understanding of the mechanisms involved in the development and maintenance of posttraumatic stress. Continued research in this area is needed to explore how trauma appraisals can be modified in the context of therapy and interventions to ameliorate the negative effects of trauma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health [grant number R01-MH066079] and the Duke Behavioral Medicine Research Center.

Contributor Information

Christin M. Ogle, Duke University

David C. Rubin, Duke University and Aarhus University

Ilene C. Siegler, Duke University and Duke University Medical Center

References

- Berntsen D, Rubin DC. The Centrality of Event Scale: A measure of integrating a trauma into one’s identity and its relation to post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:219–231. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntsen D, Rubin DC. When a trauma becomes a key to identity: Enhanced integration of trauma memories predicts posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2007;21:417–431. [Google Scholar]

- Berntsen D, Rubin DC, Siegler IC. Two versions of life: Emotionally negative and positive life events have different roles in the organization of life story and identity. Emotion. 2011;11:1190–1201. doi: 10.1037/a0024940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besser A, Neria Y, Haynes M. Adult attachment, perceived stress, and PTSD among civilians exposed to ongoing terrorist attacks in Southern Israel. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;47:851–857. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL) Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:669–673. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blix I, Solberg Ø, Heir T. Centrality of event and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder after the 2011 Oslo bombing attack. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2014;28:249–253. [Google Scholar]

- Boals A. Events that have become central to identity: Gender differences in the Centrality of Events Scale. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2010;24:107–121. [Google Scholar]

- Boals A, Hayslip B, Knowles LR, Banks JB. Perceiving a negative event as central to one’s identity partially mediates age differences in posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Journal of Aging and Health. 2012;24:459–474. doi: 10.1177/0898264311425089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen PA. The centrality of a loss and its role in emotional problems among bereaved people. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47:616–622. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Attachment. Vol. 1. New York: Basic Books; 1969/1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Separation, anxiety, and anger. NY: Basic Books; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. Routledge; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson E. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48:216–222. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810270028003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:748–766. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL. Working models of attachment: Implications for explanation, emotion, and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:810–832. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.4.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creasey G. Psychological distress in college-aged women: Links with unresolved/preoccupied attachment status and the mediating role of negative mood regulation expectancies. Attachment & Human Development. 2002;4:261–277. doi: 10.1080/14616730210167249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declercq F, Willemsen J. Distress and posttraumatic stress disorders in high risk professionals: Adult attachment style and the dimensions of anxiety and avoidance. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2006;13:256–263. [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BP. Toward a typology of stressful events and situations in posttraumatic stress disorder and related psychopathology. Psychological Injury and Law. 2010;3:89–99. doi: 10.1007/s12207-010-9072-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein RS, Ghetti S, Quas J, Goodman GS, Alexander K, Redlich AD, Cordón IM. Individual differences in emotional memory: Adult attachment and long-term memory for child sexual abuse. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:1537–1548. doi: 10.1177/0146167205277095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein RS, Gillath O. Avoiding interference: Adult attachment and emotional processing biases. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2008;34:171–181. doi: 10.1177/0146167207310024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Bonanno GA. Attachment and loss: A test of three competing models on the association between attachment-related avoidance and adaptation to bereavement. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30:878–890. doi: 10.1177/0146167204264289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Fazzari DA, Bonanno GA, Dekel S. Attachment and psychological adaptation in high exposure survivors of the September 11th attack on the World Trade Center. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:538–551. doi: 10.1177/0146167205282741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Shaver PR. Adult attachment and the suppression of unwanted thoughts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:1080–1091. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.5.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold SD, Marx BP, Soler-Baillo JM, Sloan DM. Is life stress more traumatic than traumatic stress? Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2005;19:687–698. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hooker K, Hoppmann C, Siegler IC. Personality: Life span compass for health. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2010;30:201–232. [Google Scholar]

- Kubany ES, Leisen MB, Kaplan AS, Watson SB, Haynes SN, Owens JA, Burns K. Development and preliminary validation of a brief broad-spectrum measure of trauma exposure. Psychological Assessment. 2000;12:210–224. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster SL, Melka SE, Rodriguez BF. An examination of the differential effects of the experience of DSM-IV defined traumatic events and life stressors. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:711–717. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier Y, Sabourin S, Turgeon C. Coping strategies as moderators of the relationship between attachment and marital adjustment. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1997;14:777–791. [Google Scholar]

- Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Nolan RP, Hunter JJ, Tannenbaum DW. The relationship of attachment insecurity to subjective stress and autonomic function during acute stress in healthy adults. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2006;60:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CG, Cromer LD, DePrince AP, Freyd JJ. The role of cumulative trauma, betrayal, and appraisals in understanding trauma symptomatology. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2013;5:110–118. doi: 10.1037/a0025686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Florian V. Appraisal of and coping with a real-life stressful situation: The contribution of attachment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1995;21:406–414. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.68.4.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Florian V. The relationship between adult attachment styles and emotional and cognitive reactions to stressful events. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment Theory in Close Relationships. NY: Guildford Press; 1998. pp. 143–165. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Florian V, Weller A. Attachment styles, coping strategies, and post-traumatic psychological distress: The impact of the Gulf War in Israel. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;64:817–826. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.5.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Gillath O, Shaver PR. Activation of the attachment system in adulthood: Threat-related primes increase the accessibility of mental representations of attachment figures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:881–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Orbach I. Attachment styles and repressive defensiveness: The accessibility and architecture of affective memories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:917–925. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.68.5.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. An attachment perspective on resilience to stress and trauma. In: Kent M, Davis MC, Reich JW, editors. The resilience handbook: Approaches to stress and trauma. New York, NY: Routledge; 2014. pp. 156–168. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR, Horesh N. Attachment bases of emotion regulation and posttraumatic adjustment. In: Snyder DK, Simpson J, Hughes JN, editors. Emotion regulation in couples and families. Pathways to dysfunction and health. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006. pp. 77–99. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR, Pereg D. Attachment theory and affect regulation: The dynamics, development, and cognitive consequences of attachment-related strategies. Motivation and Emotion. 2003;27:77–102. [Google Scholar]

- Muller RT, Sicoli LA, Lemieux KE. Relationship between attachment style and posttraumatic stress symptomatology among adults who report the experience of childhood abuse. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2000;13:321–332. doi: 10.1023/A:1007752719557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor M, Elklit A. Attachment styles, traumatic events, and PTSD: A cross-sectional investigation of adult attachment and trauma. Attachment and Human Development. 2008;10:59–71. doi: 10.1080/14616730701868597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogle CM, Rubin DC, Berntsen D, Siegler IC. The frequency and impact of exposure to potentially traumatic events over the life course. Clinical Psychological Science. 2013;1:426–434. doi: 10.1177/2167702613485076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogle CM, Rubin DC, Siegler IC. Cumulative exposure to traumatic events in older adults. Aging & Mental Health. 2014;18:316–325. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.832730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:52–73. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pielage S, Gerlsma C, Schaap C. Insecure attachment as a risk factor for psychopathology: The role of stressful events. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2000;7:296–302. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinaugh DJ, McNally RJ. Trauma centrality and PTSD symptom severity in adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2011;24:483–486. doi: 10.1002/jts.20656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DC, Berntsen D, Bohni MK. A memory-based model of posttraumatic stress disorder: Evaluating basic assumptions underlying the PTSD diagnosis. Psychological Review. 2008;115:985–1011. doi: 10.1037/a0013397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DC, Dennis MF, Beckham JC. Autobiographical memory for stressful events: The role of autobiographical memory in posttraumatic stress disorder. Consciousness & Cognition. 2011;20:840–856. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DC, Feeling N. Measuring the severity of negative and traumatic events. Clinical Psychological Science. 2013;1:375–389. doi: 10.1177/2167702613483112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg DA. Adult attachment as a predictor of posttraumatic stress and dissociation. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2010;11:293–307. doi: 10.1080/15299731003780937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searle B, Meara NM. Affective dimensions of attachment styles: Exploring self-reported attachment style, gender, and emotional experience among college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1999;46:147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Shaver PR, Mikulincer M. Attachment-related psychodynamics. Attachment and Human Development. 2002;4:133–161. doi: 10.1080/14616730210154171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaver PR, Mikulincer M. Adult attachment and cognitive and affective reactions to positive and negative events. Social and Personality Psychology. 2008;2:1844–1865. [Google Scholar]

- Siegler IC, Peterson BL, Barefoot JC, Harvin SH, Dahlstrom WG, Kaplan BH, Williams RB. Using college alumni populations in epidemiologic research: The UNC Alumni Heart Study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1992;45:1243–1250. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90165-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon Z, Dekel R, Mikulincer M. Complex trauma of war captivity: A prospective study of attachment and post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38:1427–1434. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon Z, Ginzburg K, Mikulincer M, Neria Y, Ohry U. Coping with war captivity: The role of attachment style. European Journal of Personality. 1998;12:271–285. [Google Scholar]

- Sutin AR, Gilliath O. Autobiographical memory phenomenology and content mediate attachment style and psychological distress. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56:351–364. doi: 10.1037/a0014917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt MC, McWilliams LA, Campbell AG. Relations between anxiety sensitivity and attachment style dimensions. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2005;27:191–200. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD checklist (PCL). Scale available from the National Center for PTSD. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Wei M, Russell DW, Mallinckrodt B, Vogel DL. The Experiences in Close Relationship Scale (ECR)-Short Form: Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2007;88:187–204. doi: 10.1080/00223890701268041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.