Abstract

Background

Lung morphogenesis is regulated by interactions between the canonical Wnt/β-catenin and Kras/ERK/Foxm1 signaling pathways that establish proximal-peripheral patterning of lung tubules. How these interactions influence the development of respiratory epithelial progenitors to acquire airway as compared to alveolar epithelial cell fate is unknown. During branching morphogenesis, SOX9 transcription factor is normally restricted from conducting airway epithelial cells and is highly expressed in peripheral, acinar progenitor cells that serve as precursors of alveolar type 2 (AT2) and AT1 cells as the lung matures.

Results

To identify signaling pathways that determine proximal-peripheral cell fate decisions, we used the SFTPC gene promoter to delete or overexpress key members of Wnt/β-catenin and Kras/ERK/Foxm1 pathways in fetal respiratory epithelial progenitor cells. Activation of β-catenin enhanced SOX9 expression in peripheral epithelial progenitors, whereas deletion of β-catenin inhibited SOX9. Surprisingly, deletion of β-catenin caused accumulation of atypical SOX9-positive basal cells in conducting airways. Inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by KrasG12D or its downstream target Foxm1 stimulated SOX9 expression in basal cells. Genetic inactivation of Foxm1 from KrasG12D-expressing epithelial cells prevented the accumulation of SOX9-positive basal cells in developing airways.

Conclusions

Interactions between the Wnt/β-catenin and the Kras/ERK/Foxm1 pathways are essential to restrict SOX9 expression in basal cells.

Keywords: lung development, forkhead transcription factor, transgenic mice, Foxm1, basal cells

Introduction

Lung function is regulated by complex interactions between foregut endodermally-derived epithelial progenitors and mesenchymal cells, which activate transcriptional programs critical for branching morphogenesis. Epithelial progenitors acquire either peripheral cell fates, marked by expression of SOX9 or proximal cell fates marked by SOX2. These cell fate decisions are critical for differentiation of multiple epithelial cell types that line alveoli and conducting airways (Warburton et al., 1999; Cardoso, 2001; Whitsett et al., 2004; Morrisey and Hogan, 2010). During branching morphogenesis, proliferation and differentiation of epithelial progenitor cells are regulated by multiple signaling pathways, including tyrosine kinases, G protein coupled receptors, FGFs, TGF-β, BMPs, retinoic acid (RA), Hippo/YAP, glucocorticoid receptor, Wnt/β-catenin and Notch (Hogan and Yingling, 1998; Whitsett et al., 2004; Morrisey and Hogan, 2010). Activation of transcription factors, including the SOX, FOX, NKX, RAR and KLF families, are critical for precise regulation of proliferation and differentiation of the respiratory epithelium (Warburton et al., 1999; Cardoso, 2001; Costa et al., 2001; Kalinichenko et al., 2001; Whitsett et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2005a; Morrisey and Hogan, 2010). Abnormalities in morphogenetic signaling pathways are associated with various congenital and acquired pulmonary disorders, including bronchopulmonary dysplasia, cystic fibrosis, interstitial lung disease, alveolar capillary dysplasia, and lung cancer (Whitsett et al., 2004; Warburton et al., 2010).

Genetic deletion of Wnt2 and Wnt2b in the splanchnic mesenchyme, or endoderm-specific deletion of β-catenin caused lung agenesis, indicating the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is required for specification of the lung field (Goss et al., 2009). Deletion of β-catenin from respiratory epithelial lineages using the SFTPC gene promoter disrupted branching lung morphogenesis, causing enlarged bronchiolar tubules and loss of peripheral lung (Mucenski et al., 2003). Expression of activated β-catenin in respiratory epithelial cells disrupted alveolarization (Mucenski et al., 2005). Previous studies demonstrated that multiple ligands, including FGFs, HGF, BMPs, Wnt2 and Wnt7b, activate ERK1/2 (MAPK3 and MAPK1) which phosphorylate proteins critical for epithelial proliferation, migration and survival (Morrisey and Hogan, 2010). Reduced epithelial branching was observed in fetal lung explants treated with MEK-1/2 inhibitor (Kling et al., 2002). Expression of an activated KrasG12D in respiratory epithelial cells impaired branching lung morphogenesis, increased MAPK activity and induced expression of Sprouty-2, a Ras/ERK antagonist (Shaw et al., 2007). Foxm1 transcription factor is a key downstream target of the Kras/ERK signaling pathway and an important regulator of cellular proliferation during embryonic development, organ injury and carcinogenesis (Bolte et al., 2011; Balli et al., 2012; Bolte et al., 2012; Sengupta et al., 2013; Cheng et al., 2014; Xia et al., 2015). Kras downstream kinases, including ERK, Cdk1 and Cdk2, directly phosphorylate Foxm1 and induce its transcriptional activity (Major et al., 2004; Ma et al., 2005). Transgenic expression of Foxm1 was sufficient to disrupt branching lung morphogenesis, partially recapitulating KrasG12D defects (Wang et al., 2012). Genetic deletion of Foxm1 from respiratory epithelial cells prevented branching abnormalities in KrasG12D-expressing embryos (Wang et al., 2012) and inhibited KrasG12D-mediated lung carcinogenesis in adult mice (Wang et al., 2014), indicating that Foxm1 is required for Kras/ERK signaling in respiratory epithelium. Recent studies demonstrated that the Kras/ERK/Foxm1 signaling pathway inhibits canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling during lung development (Wang et al., 2012), however, these signaling pathways synergize to stimulate lung carcinogenesis in adult mice (Pacheco-Pinedo et al., 2011). Given the complexity of crosstalk between the Kras/ERK/Foxm1 and the Wnt/β-catenin pathways, it is still unknown how this crosstalk influences epithelial cell fate decisions in the developing lung.

SOX9 and SOX2 are members of the family of Sox (Sry - sex-determining region of Y chromosome) transcription factors that share a High-mobility group (HMG) box DNA binding domain (reviewed in (Kamachi et al., 2000; Pritchett et al., 2011; Sarkar and Hochedlinger, 2013)). During branching morphogenesis of the lung, SOX9 and SOX2 are expressed in distinct epithelial compartments along the proximal and peripheral axis of the lung tubules. SOX9 is expressed in peripheral epithelial progenitors that give rise to alveolar epithelial cells type I and type II; SOX2 is restricted to epithelial cells in the proximal, conducting regions of the lung that serve as progenitors of ciliated, basal, goblet and Club cells (Perl et al., 2005; Rawlins, 2011; Turcatel et al., 2013). While recent studies with transgenic mice supported a role for SOX9 and SOX2 in branching lung morphogenesis and differentiation of respiratory epithelial progenitors (Morrisey and Hogan, 2010; Chang et al., 2013; Rockich et al., 2013), molecular mechanisms restricting SOX9 and SOX2 along the proximal to peripheral axis of the lung tubules remain unclear. In the present study, we demonstrate that Wnt/β-catenin and the Kras/Foxm1 signaling pathways differentially regulate expression of SOX9 and SOX2 during branching lung morphogenesis.

Results

β-Catenin induces SOX9 in lung epithelial progenitors

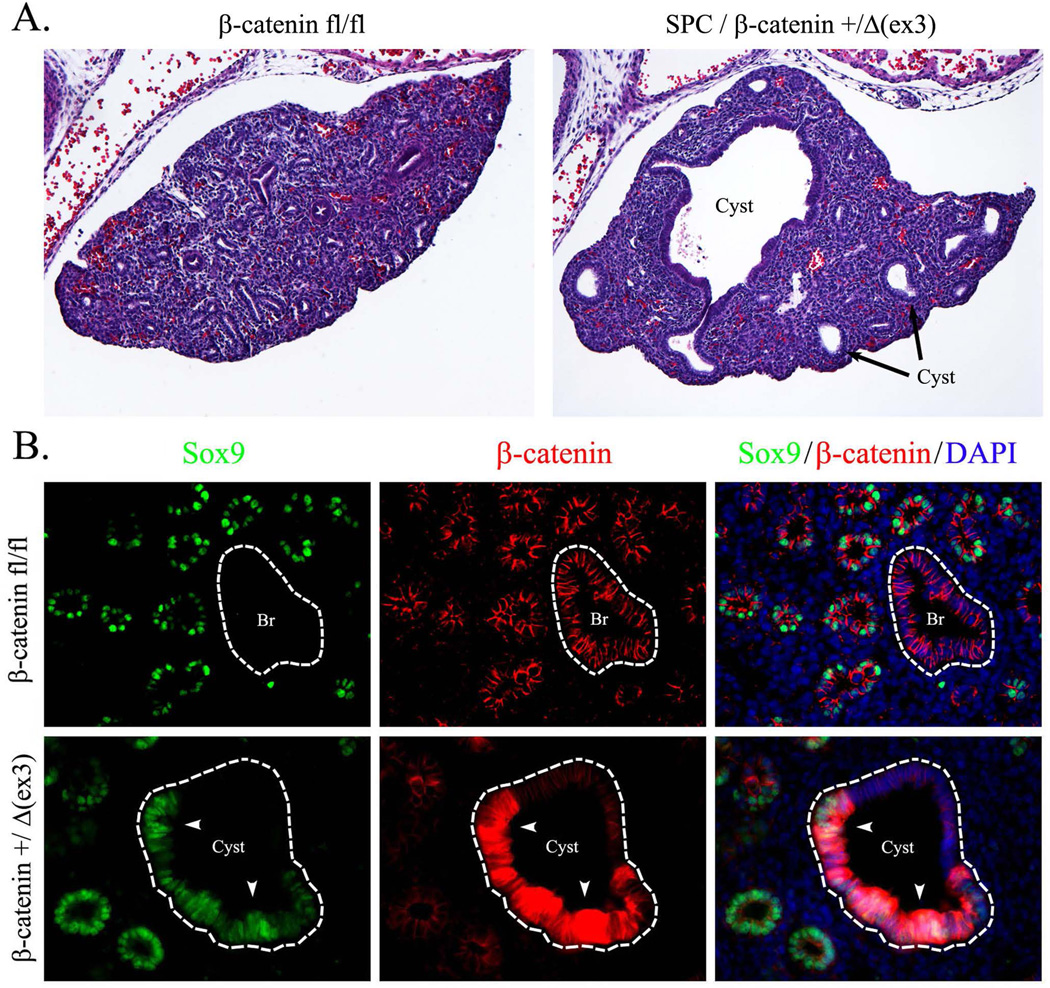

β-Catenin and SOX9 are co-expressed in peripheral epithelial progenitors during branching lung morphogenesis (Rockich et al., 2013). To determine whether activation of β-catenin influences SOX9 expression, the Doxycycline (Dox)-regulated SFTPC promoter was used to express an activated form of β-catenin (β-cateninΔex3) (Mucenski et al., 2005) in respiratory epithelial cells of SPC-rtTA/TetO-Cre/β-catenin+/Δ(ex3) mouse embryos. To activate Cre, Dox was given from E0.5 to E14.5. In this transgenic mouse line, Dox caused mosaic expression of β-cateninΔex3, targeting a subset of epithelial cells in peripheral (acinar) and proximal (bronchiolar) epithelial compartments. Consistent with previous studies (Hashimoto et al., 2012), activation of β-catenin in respiratory epithelium disrupted branching morphogenesis as evidenced by the presence of enlarged epithelial cysts at E14.5 (Fig. 1A). Activated β-catenin induced SOX9 in cystic lesions in the peripheral lung (Fig. 1B). Activation of β-catenin caused ectopic expression of SOX9 in the bronchiolar epithelium (Fig. 2A). SOX9 was detected in a subset of bronchiolar epithelial cells that lost normal expression of SOX2 (Fig. 2A), a transcription factor selectively expressed in proximal epithelial cells in the developing lung (Morrisey and Hogan, 2010). Immunostaining using antibodies against SOX2, SOX9, and β-catenin detected bronchiolar epithelial cells with intense staining for β-catenin that expressed SOX9 and lacked SOX2 (Fig. 2B). Thus, β-cateninΔex3 disrupted normal SOX9/SOX2 patterning in the developing lung.

Figure 1. Activation of β-catenin in respiratory epithelium induces SOX9.

Paraffin sections were prepared from E14.5 embryos. Dox was given to pregnant mice after identification of a vaginal plug (E0.5). Slides were stained with Hematoxilin and Eosin (H&E) or used for immunostaining with β-catenin and SOX9 antibodies. SPC-rtTA/TetO-Cre/β-catenin+/Δ(ex3) lungs show abnormal cyst-like structures in the lung tissue (A). Activated β-catenin increases SOX9 staining in cystic epithelium (B, arrowheads). DAPI was used to label cell nuclei. Abbreviations: Br, bronchi. Magnifications: ×100 (A) and ×400 (B).

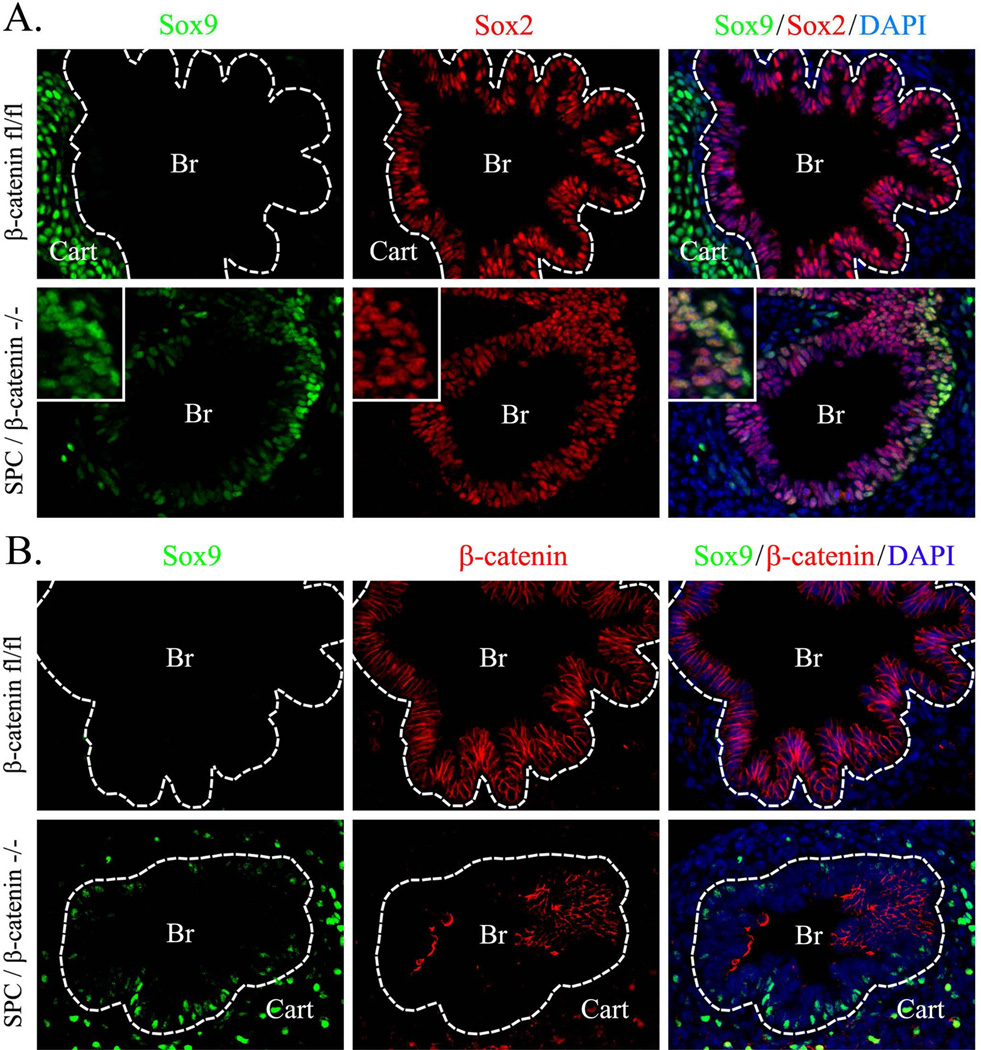

Figure 2. SOX9 replaces SOX2 in airway epithelium of SPC-rtTA/TetO-Cre/β-catenin+/Δ(ex3) mice.

Lung sections from Dox-treated SPC-rtTA/TetO-Cre/β-catenin+/Δ(ex3) and control β-cateninfl/fl E14.5 embryos were stained for SOX9, SOX2 and β-catenin. Ectopic expression of SOX9 and loss of SOX2 is observed in airway epithelium of SPC-rtTA/TetO-Cre/β-catenin+/Δ(ex3) mice (A). Triple immunostaining for SOX9, SOX2 and β-catenin revealed that the highest expression of β-catenin is associated with the loss of SOX2 and aberrant expression of SOX9 in airway epithelial cells (B, arrowheads). DAPI was used to label cell nuclei. Dotted lines indicate boundaries of epithelial layers in pulmonary bronchi. Abbreviations: Br, bronchi. Magnification is ×400.

Conditional deletion of β-catenin inhibits SOX9

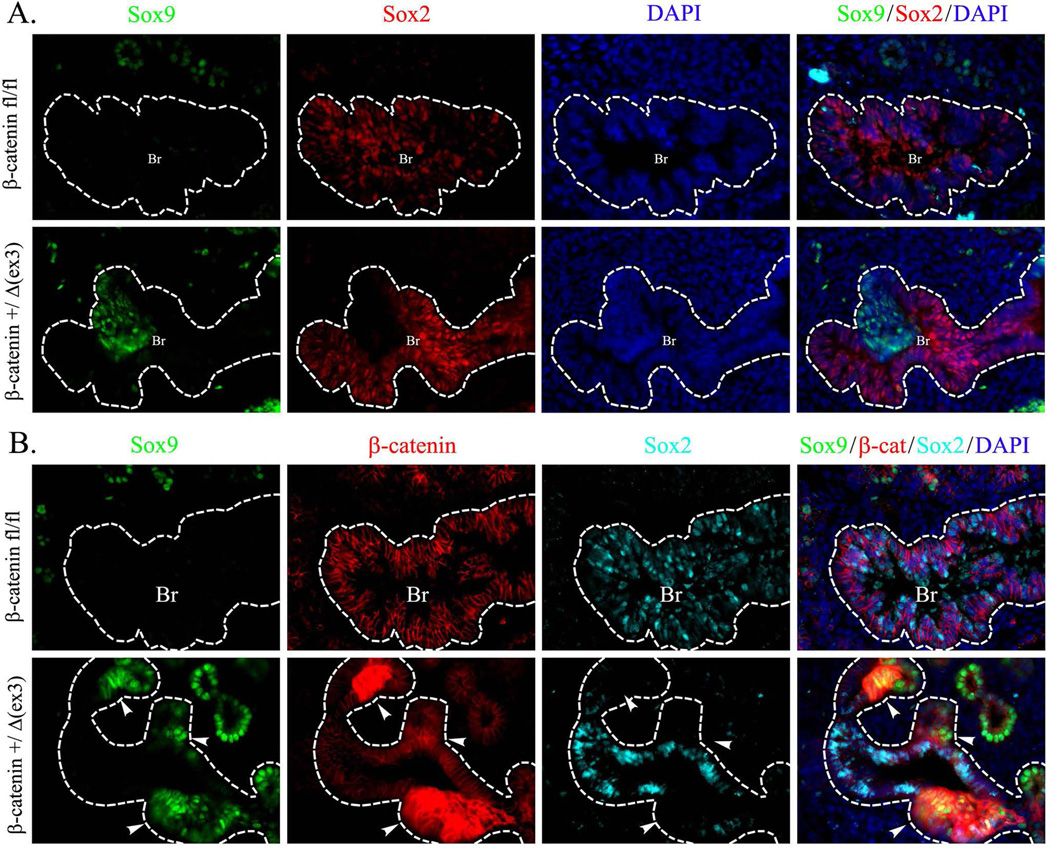

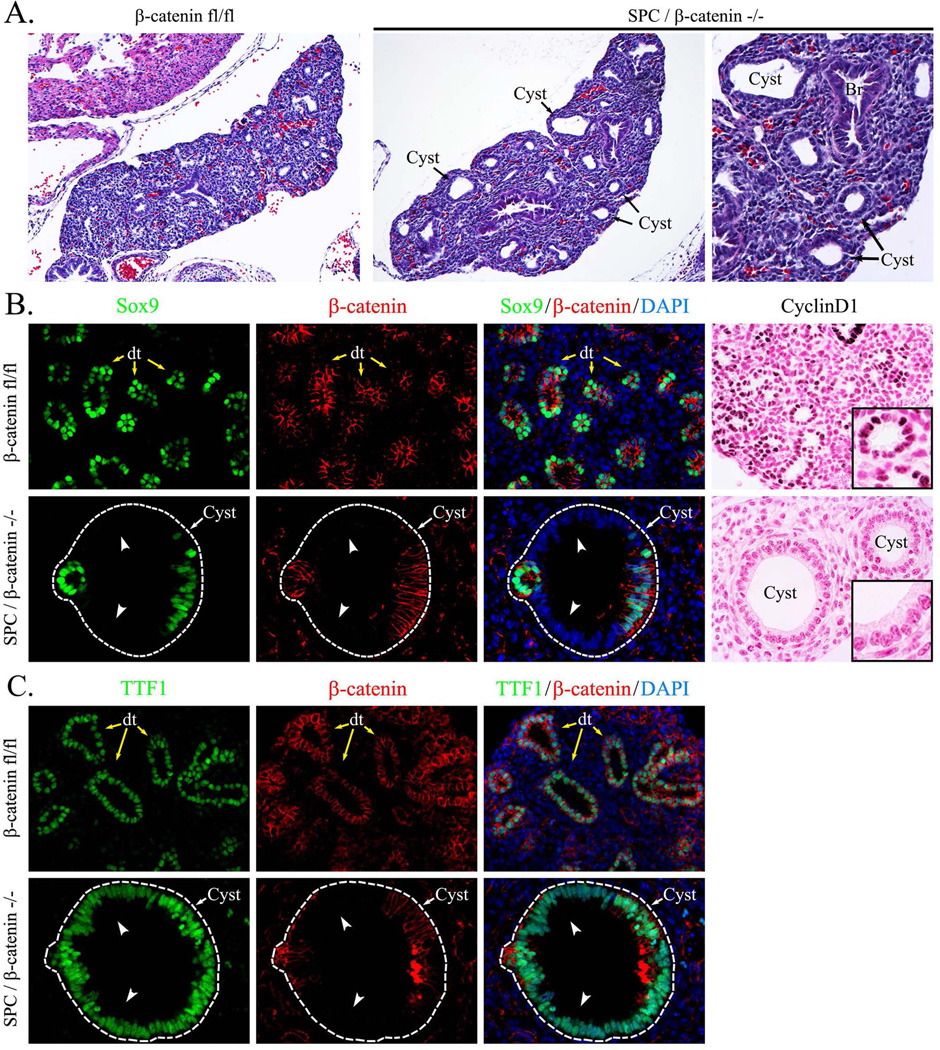

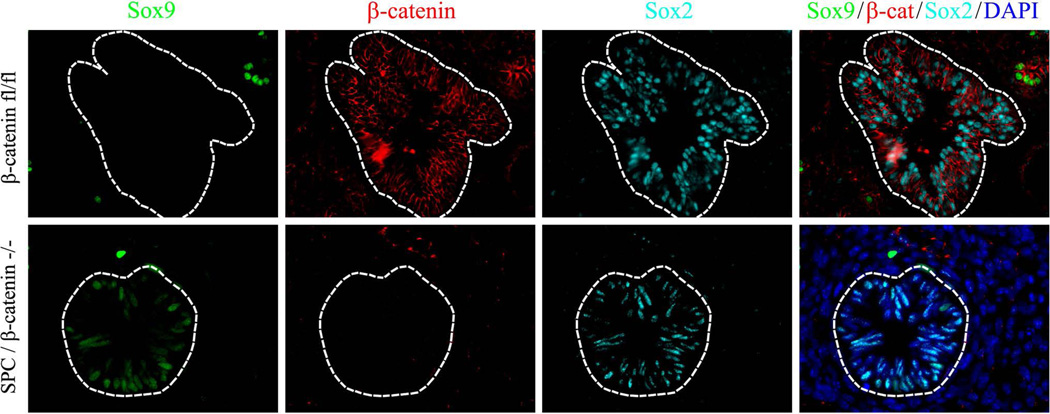

Since exogenous β-cateninΔex3 increased SOX9 in the developing respiratory epithelium (Figs. 1–2), we tested whether genetic inactivation of β-catenin gene altered SOX9 expression. Dox-mediated inactivation of β-catenin-floxed alleles was performed in SPC-rtTA/tetO-Cre/β-cateninfl/fl triple transgenic embryos from E0.5 to E14.5. Deletion of β-catenin caused enlargement of epithelial tubules in E14.5 lungs (Fig. 3A). Epithelial cells lacking β-catenin were negative for SOX9 (Fig. 3B) but maintained expression of NKX2-1 (TTF-1) (Fig. 3C), a transcription factor critical for differentiation of respiratory epithelial cells (Whitsett et al., 2004). These data indicate that β-catenin-deficient epithelial cells lost SOX9 but maintained respiratory epithelial cell identity as indicated by expression of NKX2-1. Deletion of β-catenin reduced expression of the Wnt/β-catenin target gene Cyclin D1 in distal cystic epithelium (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, deletion of β-catenin did not alter SOX2 in the bronchiolar epithelium at E14.5 or E16.5 (Fig. 4 and data not shown), indicating that β-catenin was not required for acquisition of proximal epithelial cell fate.

Figure 3. Inactivation of β-catenin inhibits SOX9 in the peripheral lung.

Paraffin sections were prepared from E14.5 embryos. Dox was given to pregnant mice after identification of a vaginal plug (E0.5). Slides were stained with Hematoxilin and Eosin (H&E) or used for immunostaining with β-catenin, SOX9 and TTF-1 (Nkx2.1) antibodies. Dox-treated SPC-rtTA/tetO-Cre/β-cateninfl/fl (SP-C/β-catenin−/−) embryos showed enlarged epithelial cysts in peripheral lung regions (A). Loss of β-catenin did not affect TTF-1 (C) but decreased SOX9 and Cyclin D1 in cystic lung epithelium (B, arrowheads). DAPI was used to label cell nuclei. Yellow arrows show distal epithelial tubules. White arrows show epithelial cysts. Abbreviations: Br, bronchi; Cyst, peripheral epithelial cysts; dt, distal tubules. Magnifications: ×100 (A); ×200 (right panel in A); ×400 (B–C); and ×800 (inserts).

Figure 4. Deletion of β-catenin in the lung epithelium does not affect SOX2 expression.

Paraffin sections were prepared from E14.5 embryos. Dox was given to pregnant mice from E0.5 to E14.5. Slides were immunostained for SOX9 (green), SOX2 (cyan) and β-catenin (red). Deletion of β-catenin does not influence expression of SOX2 in airway epithelial cells. Magnification is ×400.

Accumulation of basal cells after deletion of ß-catenin

SOX9 is not expressed in conducting airway epithelial cells but is expressed in tracheal-bronchial cartilage at E14.5-E16.5 (Fig. 5A). Deletion of β-catenin resulted in accumulation of SOX9-positive cells within epithelial compartments in both cartilaginous and non-cartilaginous airways of E14.5 embryos (Figs. 4 and 5A–B). SOX9 and SOX2 were co-expressed in a subset of epithelial cells of β-catenin-deficient airways (Figs. 4 and 5A). To determine the identity of these atypical SOX9-positive cells, we examined markers of airway epithelial lineages. These atypical SOX9-positive cells did not express β-tubulin, CCSP, proSP-C or cytokeratin 5, but were positive for p63 (Fig. 6A, 6D and data not shown), a basal cell marker (Rawlins et al., 2009; Rock et al., 2009). Cells expressing SOX9 were also positive for T1α (Fig. 6B), which is expressed in basal cells of conducting airways at E14.5 (Rawlins et al., 2009). Numbers of SOX9-positive basal cells and total basal cell number were increased in β-catenin-deficient lungs (Fig. 6C). Interestingly, β-catenin was undetectable in the SOX9-positive basal cells (Fig. 5B), suggesting that loss of β-catenin induced SOX9 expression in basal cells. SOX9-positive basal cells were also detected in peripheral airways of ß-catenin-deficient E12.5 embryos (Fig. 7A–C) and E16.5 embryos (Fig. 8) but not in controls (Figs. 7–8). Thus, inactivation of β-catenin during branching lung morphogenesis causes the accumulation of ectopic SOX9-positive basal cells in conducting airways.

Figure 5. Inactivation of β-catenin results in aberrant expression of SOX9 in a subset of airway epithelial cells.

Paraffin sections were prepared from E14.5 lungs obtained from Dox-treated SPC-rtTA/tetO-Cre/β-cateninfl/fl (SPC/β-catenin−/−) and control β-cateninfl/fl embryos. Dox was given to pregnant mice after identification of a vaginal plug (E0.5) until the animal harvest. Slides were immunostained for SOX9, SOX2 (A) and β-catenin (B). β-catenin-deficient embryos show aberrant expression of SOX9 in airway epithelium, which was identified by SOX2 (A–B). Dotted lines indicate boundaries of epithelial layers in pulmonary bronchi. Abbreviations: Br, bronchi; Cart, cartilage. Magnifications: main images, ×400; inserts, ×800.

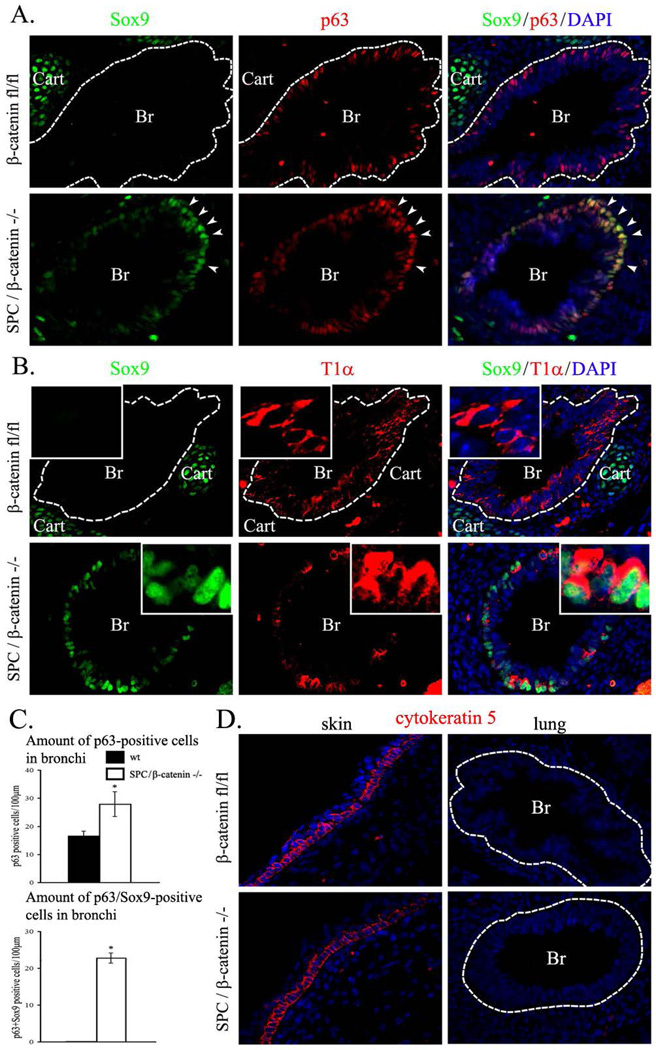

Figure 6. Inactivation of β-catenin increases the numbers of basal cells and causes accumulation of SOX9-positive basal cells in E14.5 lungs.

A–B, SOX9 co-localizes with basal cell markers in β-catenin-deficient airway epithelium. Paraffin sections were prepared from E14.5 lungs obtained from Dox-treated SPC-rtTA/tetO-Cre/β-cateninfl/fl (SPC/β-catenin−/−) and control β-cateninfl/fl embryos. Dox was given to pregnant mice after identification of a vaginal plug (E0.5) until the animal harvest. Slides were immunostained for SOX9, p63 and T1α. Dotted lines indicate boundaries of epithelial layers in pulmonary bronchi. β-Catenin-deficient embryos show co-localization of SOX9 with p63 (A, arrows). Nuclear SOX9 staining is observed in T1α-positive basal cells (B, inserts). C, Inactivation of β-catenin increases the number of basal cells in airway epithelium. The numbers of p63-positive and p63/SOX9 double-positive cells were counted in 20 airway regions selected randomly (n=5 embryos in each group). * indicates statistically significant changes (p < 0.05). D, Cytokeratin 5 is not expressed in basal cells of SPC/β-catenin−/− and β-cateninfl/fl E14.5 lungs. Cytokeratin 5 is present in skin of SPC/β-catenin−/− and β-cateninfl/fl E14.5 embryos. Abbreviations: Br, bronchi; Cart, cartilage. Magnifications: ×400; inserts, ×1500.

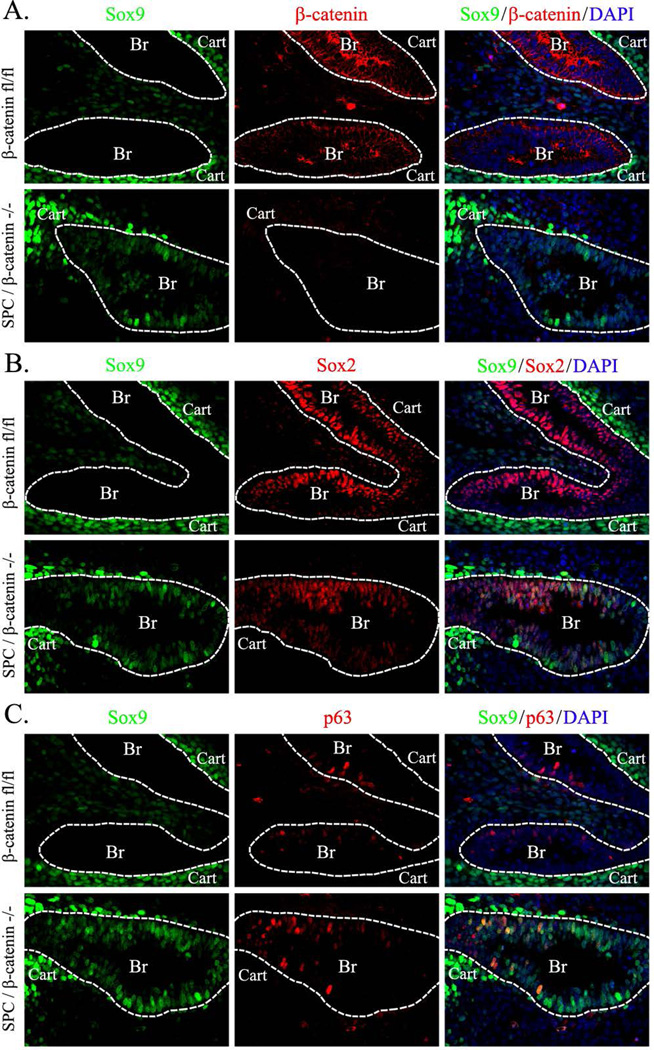

Figure 7. Deletion of β-catenin induces SOX9 in conducting airways and increases the number of basal cells at E12.5.

Paraffin sections were prepared from E12.5 embryos. Dox was given to pregnant mice from E0.5 to E12.5. Lung sections were immunostained for SOX9, SOX2, β-catenin and p63. DAPI was used to label cell nuclei. Dox-treated SPC-rtTA/tetO-Cre/β-cateninfl/fl (SPC/β-catenin−/−) lungs show accumulation of SOX9-positive basal cells in conducting airways (dotted lines). Abbreviations: Br, bronchi; Cart, cartilage. Magnification is ×400.

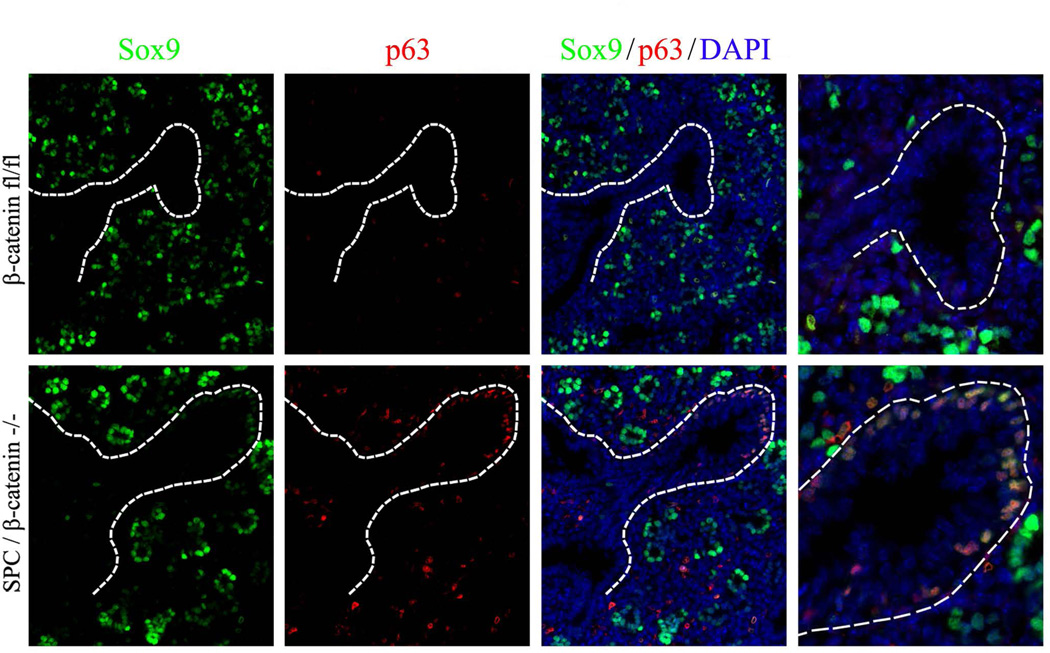

Figure 8. Inactivation of β-catenin causes accumulation of SOX9-positive basal cells in developing airways of E16.5 embryos.

Paraffin sections were prepared from E16.5 embryos. Dox was given to pregnant mice from E0.5 to E16.5. Slides were immunostained for SOX9 (green) and p63 (red). DAPI was used to label cell nuclei (blue). Dox-treated SPC-rtTA/tetO-Cre/β-cateninfl/fl (SPC/β-catenin−/−) lungs show accumulation of SOX9-positive basal cells in developing airways (shown by dotted lines). Magnifications: left and middle panels, ×400; right panels, ×800.

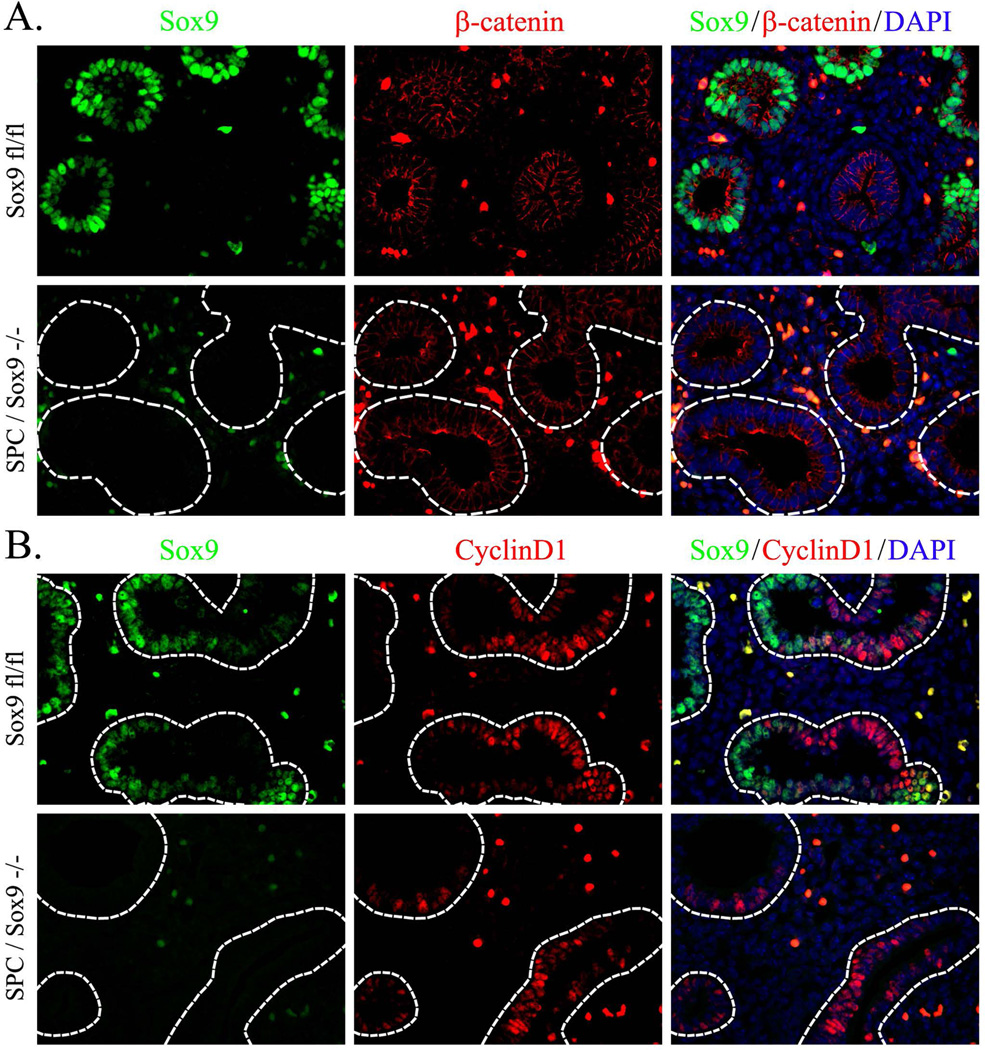

Deletion of SOX9 from respiratory epithelium does not alter β-catenin

Since SOX9 was previously implicated in the regulation of β-catenin in chondrocytes and neoplastic cells (Topol et al., 2009; Pritchett et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2015), we examined whether SOX9 regulates β-catenin in developing respiratory epithelium. Dox-induced deletion of Sox9 from SPC-rtTA/TetO-Cre/Sox9fl/fl embryos did not affect expression of β-catenin at any developmental time-points examined (E12.5, E14.5, and E18.5) despite a near complete loss of SOX9 from lung epithelial compartments (Fig. 9A and data not shown). Consistent with these results, transcriptional target of β-catenin, Cyclin D1, was unaltered in SPC-rtTA/TetO-Cre/Sox9fl/fl embryos (Fig. 9B). Thus, SOX9 does not regulate β-catenin in respiratory epithelial progenitors.

Figure 9. SOX9 does not affect expression of β-catenin in the developing respiratory epithelium.

Paraffin sections were prepared from E14.5 lungs obtained from Dox-treated SPC-rtTA/tetO-Cre/Sox9fl/fl (SPC/Sox9−/−) and control Sox9fl/fl embryos. Dox was given to pregnant mice after identification of a vaginal plug (E0.5) until the animal harvest. Slides were immunostained for β-catenin, SOX9 and Cyclin D1. DAPI was used to label cell nuclei. SOX9 and β-catenin are co-expressed in distal respiratory epithelium of control lungs (A). Deletion of SOX9 does not affect expression of β-catenin (A) or Cyclin D1. Magnification is ×400.

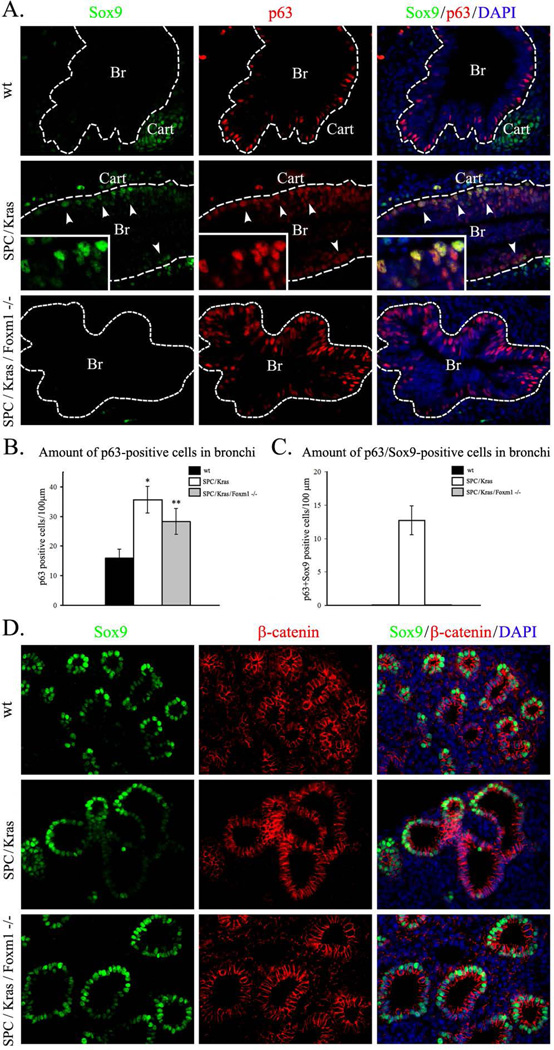

Activated KrasG12D and Foxm1 inhibit ß-catenin and induce SOX9 in basal cells

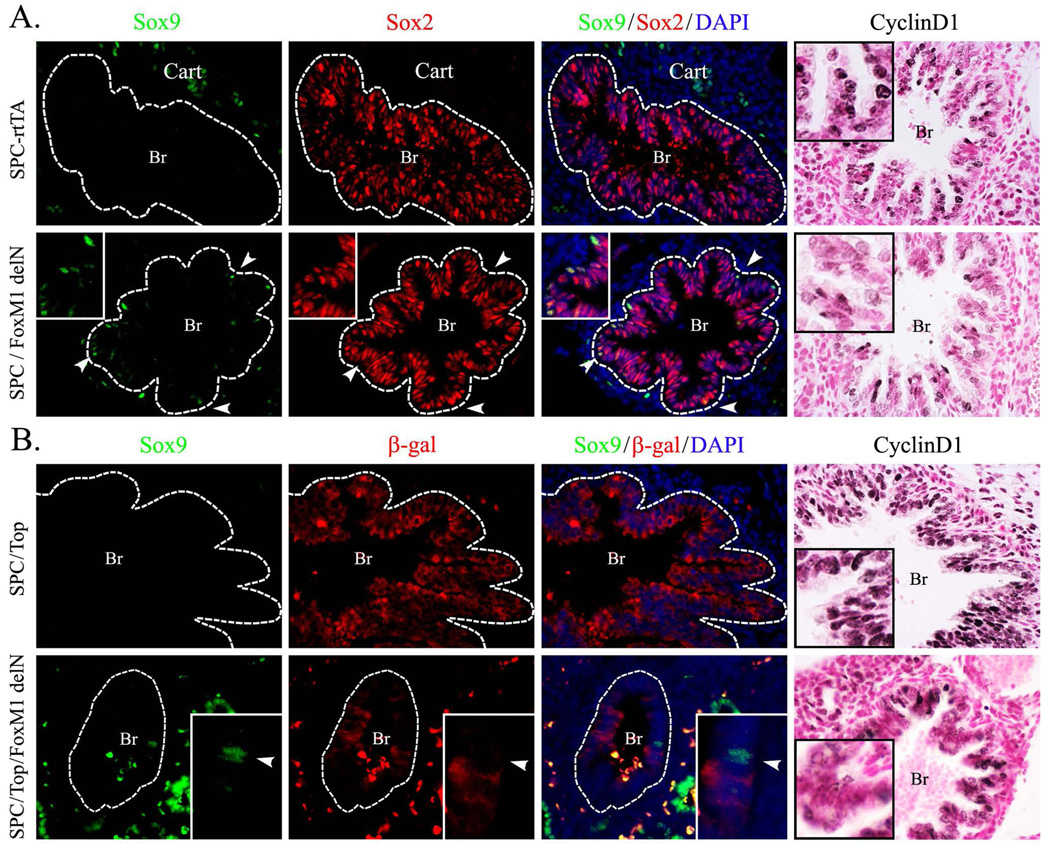

Expression of either activated KrasG12D or its downstream target, the Foxm1 transcription factor, in respiratory epithelial progenitors inhibited canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Wang et al., 2012). Therefore, we examined whether KrasG12D or activated Foxm1 mutant (FoxM1-delN) (Wang et al., 2010) influences SOX9 expression in respiratory epithelium. SPC-rtTA/TetO-KrasG12D and SPC-rtTA/TetO-FoxM1-delN embryos, in which transgenes were conditionally activated from E0.5 to E14.5, were generated and examined for SOX9. Expression of KrasG12D caused accumulation of atypical SOX9-positive basal cells in the developing airway epithelium, as atypical basal cells expressed both p63 and SOX9 (Fig. 10A, middle panels and 10B–C). Similar to KrasG12D, expression of FoxM1-delN increased SOX9 in airway epithelium (Fig. 11A). Atypical SOX9-expressing cells in the developing FoxM1-delN airways were positive for SOX2 (Fig. 11A). A TOPGAL reporter demonstrated lack of Wnt/β-catenin activity in these SOX9-positive basal cells (Fig. 11B). Expression of Wnt/β-catenin target gene Cyclin D1 was reduced in airway epithelium of FoxM1-delN embryos (Fig. 11A–B). Neither KrasG12D nor FoxM1-delN influenced SOX9 in peripheral epithelial tubules (Fig 10D and data not shown). Thus, inhibition of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling by Kras/Foxm1 stimulated SOX9 expression in basal cells of conducting airways.

Figure 10. Expression of KrasG12D causes accumulation of SOX9-positive basal cells in developing airways.

A, Expression of activated KrasG12D induces SOX9 in airway basal cells. Paraffin sections were prepared from E14.5 lungs obtained from Dox-treated SPC-rtTA/tetO-KrasG12D/tetO-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl quadruple transgenic embryos (SPC/Kras/Foxm1−/−) and their SPC-rtTA/tetO-KrasG12D/Foxm1fl/fl triple transgenic littermates (SPC/Kras). Additional controls included E14.5 wild type (wt) embryos that have been treated with Dox from E0.5 to E14.5. Slides were immunostained for SOX9 and p63. DAPI was used to stain cell nuclei. SOX9 co-localized with p63 in SPC/Kras airways (arrowheads and inserts). SOX9 was not observed in airway epithelium of wt and SPC/Kras/Foxm1−/− embryos. B–C, Kras activation increases the total number of basal cells and induces SOX9 expression in basal cells of conducting airways. The number of p63-positive and p63/SOX9 double-positive cells was counted in 20 airway regions selected randomly (n=5 embryos in each group). SPC/Kras/Foxm1−/− embryos show a decrease in total number of basal cells (B) and the number of p63/SOX9-positive basal cells (C). * indicates p < 0.01. ** indicates p < 0.05. D, KrasG12D does not influence SOX9 in distal lung epithelium. Distal epithelial tubules of SPC/Kras and SPC/Kras/Foxm1−/− embryos maintain expression of SOX9 and β-catenin. Abbreviations: Br, bronchi; Cart, cartilage. Magnifications: A and D, ×400; inserts, ×1000.

Figure 11. Expression of Foxm1 causes accumulation of SOX9-positive basal cells in developing airways.

A, Expression of activated Foxm1 mutant (FoxM1-delN) is sufficient to induce SOX9 in the developing airway epithelium. Dox-treated SPC-rtTA/TetO-FoxM1-delN embryos were harvested at E14.5 and compared to SPC-rtTA littermates. SOX9-positive cells are detected in airway epithelium (shown by dotted lines) of SPC-rtTA/TetO-FoxM1-delN embryos (arrowheads and inserts) but not in controls. Cyclin D1 is decreased in airway epithelium of SPC-rtTA/TetO-FoxM1-delN embryos. B, SOX9-positive basal cells lack TOPGAL activity. Dox-treated SPC-rtTA/TetO-FoxM1-delN/TOPGAL embryos were harvested at E14.5 and compared to SPC-rtTA/TOPGAL littermates. FoxM1-delN mutant decreases β-gal expression in airway epithelial cells. SOX9 positive cells are detected in airway epithelium of SPC-rtTA/TetO-FoxM1-delN embryos (bottom panels) but not in controls (upper panels). SOX9 did not co-localize with β-gal in SPC-rtTA/TetO-FoxM1-delN/TOPGAL airway epithelial cells (inserts). Yellow signal indicates auto-fluorescence from red blood cells. Abbreviations: Br, bronchi; Cart, cartilage. Magnifications: A–B, ×400; inserts in A, ×800; inserts in B ×1000.

Foxm1 is required for KrasG12D–mediated activation of SOX9 in basal cells

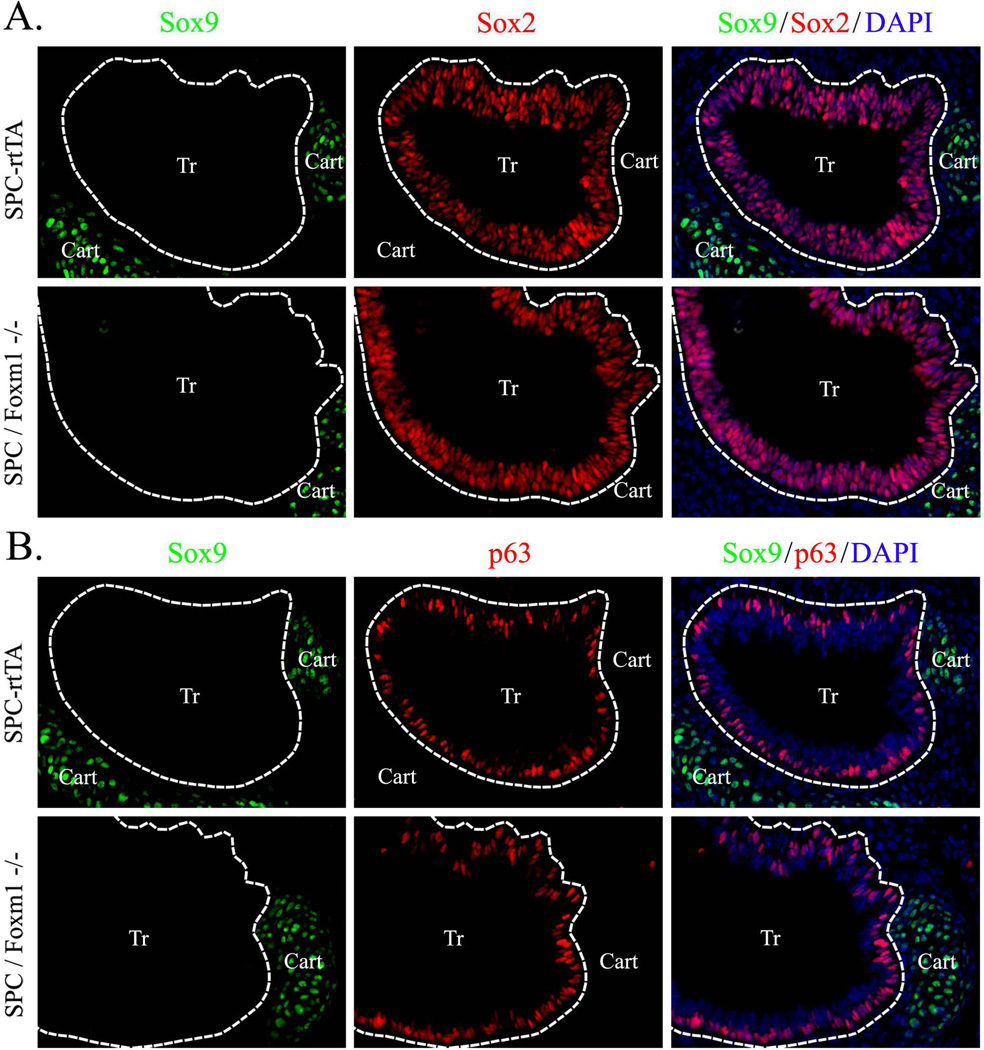

Since Foxm1 is required for Kras signaling in respiratory epithelial cells during embryonic development (Wang et al., 2012), we generated mouse embryos to simultaneously activate KrasG12D and delete Foxm1 from respiratory epithelial cells (SPC-rtTA/TetO-KrasG12D/TetO-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl). Deletion of Foxm1 from KrasG12D–expressing epithelium prevented the accumulation of atypical SOX9-positive basal cells in developing airways (Fig. 10A, bottom panels and 10B–C). Thus, KrasG12D induced SOX9 expression in basal cells via Foxm1 transcription factor. Interestingly, in the absence of KrasG12D, deletion of Foxm1 was insufficient to induce SOX9 or change the number of basal in trachea (Fig. 12). Altogether, our data demonstrate that activation of the Kras/Foxm1 signaling pathway or inhibition of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway in lung epithelial progenitors induces SOX9 expression in basal cells.

Figure 12. Deletion of Foxm1 does not induce SOX9 in tracheal epithelium.

Paraffin sections were prepared from E14.5 tracheas obtained from Dox-treated SPC-rtTA/tetO-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl embryos (SPC/Foxm1−/−) and their SPC-rtTA/Foxm1fl/fl littermates (SPC-rtTA). Dox was given from E0.5 to E14.5. Slides were immunostained for SOX9, SOX2 (A) and p63 (B). DAPI was used to stain cell nuclei. Deletion of Foxm1 does not influence expression patterns of SOX9, SOX2 and p63 in the developing tracheal epithelium (shown by dotted lines). Abbreviations: Br, bronchi; Cart, cartilage. Magnification is ×400.

Discussion

Published studies demonstrated that canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling induces SOX9 in intestinal crypts (Blache et al., 2004). Ectopic expression of either wild type or activated β-catenin mutant increased SOX9 in gastric adenocarcinomas (Choi et al., 2014). Increased SOX9 levels were found to be associated with activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling in lung adenocarcinomas (Capaccione et al., 2014). During lung development, ectopic activation of the canonical Wnt pathway expanded SOX9-expressing epithelial domain in the peripheral lung (Hashimoto et al., 2012). All these studies are consistent with the hypothesis that the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway directly or indirectly induces SOX9. In contrast to these published studies, SOX9 was not changed in distal respiratory progenitors when β-catenin was deleted using Sox9-CreER (Rockich et al., 2013). In the present studies, we used SFTPC (SPC) promoter to delete β-catenin from respiratory epithelial progenitors. The SPC-rtTA/TetO-Cre system targets both proximal and distal epithelial compartments when Dox is given from E0.5 to E14.5 (Perl et al., 2002). In the present study, we found that SPC-directed deletion of β-catenin inhibits SOX9 during lung development, suggesting that SOX9 is a downstream target of β-catenin in respiratory epithelial progenitors. Consistent with this hypothesis, we also found that overexpression of the activated form of β-catenin (β-cateninΔex3) increased SOX9 expression in respiratory epithelial progenitors. These results are consistent with previous studies that reported increased levels of SOX9 in mice expressing β-catenin-LEF1 fusion protein under control of SFTPC promoter (Okubo and Hogan, 2004). Apparent discrepancy between our studies and (Rockich et al., 2013) can be explained by the choice of Cre transgene. Sox9-CreER targets the peripheral (distal) lung epithelium as well as a variety of SOX9-expressing cells in multiple tissues, such as cartilage, pancreas and intestine (Blache et al., 2004; Pritchett et al., 2011). In contrast, the SPC-rtTA/TetO-Cre is specific to lung epithelium (Perl et al., 2002). It is possible that deletion of β-catenin from non-epithelial cells alters SOX9 expression in respiratory epithelial progenitors through paracrine or endocrine mechanisms. Alternatively, since Wnt/β-catenin signaling induces SOX9 transcription, deletion of β-catenin may decrease expression of the Sox9-CreER transgene, reducing Cre-mediated recombination in peripheral respiratory epithelium.

Published studies provide strong evidence that the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway negatively regulates the development of basal cells during branching lung morphogenesis. Activation of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling in developing respiratory epithelium inhibited p63, a basal cell marker (Hashimoto et al., 2012). TTF1 (Nkx2.1)-driven activation of β-catenin decreased numbers of basal cells in trachea (Li et al., 2009). Likewise, overexpression of Dkk1, a secreted inhibitor of Wnt signaling, results in the expansion of basal cells in the conducting airways (Volckaert et al., 2013). Consistent with these studies, we observed an increase in basal cells after deletion of β-catenin. Since basal cells are progenitors of airway epithelial cells (Rock et al., 2009), expansion of airway epithelial compartment seen in β-catenin-deficient embryos (Mucenski et al., 2003) can be a result of basal cell hyperplasia. Interestingly, expansion of basal cells in β-catenin-deficient lungs was due to accumulation of atypical SOX9-positive basal cells that are absent (or rare) during normal lung morphogenesis. Taken together, the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway appears to play a dual role in regulation of SOX9 in respiratory epithelial progenitors. In peripheral epithelial progenitors, Wnt/β-catenin stimulates SOX9 as indicated by reduced SOX9 and its target gene Cyclin D1 in β-catenin-deficient embryos and increased SOX9 in peripheral epithelial tubules expressing activated β-cateninΔex3. In conducting airway epithelial progenitors, Wnt/β-catenin restricts SOX9 expression in basal cells. It is not clear how this distinct regulation of SOX9 is achieved at molecular levels. It is possible that β-catenin-mediated regulation of Sox9 promoter requires a different set of co-activator proteins that are differentially expressed in peripheral epithelial progenitors as compared to basal cells. These distinct co-activators may influence β-catenin transcriptional activity, altering Sox9 expression and proximal-peripheral epithelial patterning in the developing lung. Alternatively, since β-catenin has multiple cellular functions in the developing respiratory epithelium, such as regulation of cell adhesion and cell junctions, it is also possible that “non-transcriptional” functions of β-catenin contribute to the regulation of Sox9 gene expression.

Published studies demonstrated that human lung adenocarcinomas with activating Kras mutations have increased levels of SOX9 (Capaccione et al., 2014). Activation of Kras signaling by FGFs expanded the SOX9-expressing domain in the developing lung (Chang et al., 2013). We found that transgenic expression of either activated Kras or Foxm1 was sufficient to stimulate SOX9 in basal cells and significantly increase their numbers in conducting airways. Since Fgf10 induces Kras/ERK signaling, the expansion of basal cells seen in Fgf10-overexpressing mice (Volckaert et al., 2013) can be a consequence of activated Kras/ERK/Foxm1 pathway in the developing airway epithelium. Furthermore, inhibition of Wnt signaling by Dkk1 resulted in the expansion of basal cells in the conducting airways (Volckaert et al., 2013). Since both Kras and Foxm1 inhibited Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the developing respiratory epithelium (Wang et al., 2012), it is possible that Kras/Foxm1 stimulates SOX9 expression in basal cells through inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin. Consistent with this hypothesis, SOX9-positive basal cells lacked TOPGAL activity. Altogether, the present study indicates that crosstalk between the Kras/Foxm1 and the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways is important for SOX9 expression in basal cells.

In summary, β-catenin stimulates SOX9 in peripheral epithelial progenitors but inhibit SOX9 in developing basal cells. Kras acts through Foxm1 transcription factor to inhibit Wnt/β-catenin signaling and stimulate SOX9 expression in basal cells. These results demonstrate that crosstalk between the canonical Wnt/β-catenin and the Kras/Foxm1 signaling pathways is essential to restrict SOX9 expression in basal cells during lung development.

Experimental Procedures

Mice

Animal studies were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation. Mouse embryos for these studies were generated using the following transgenic lines: SFTPC(SPC)-rtTAtg/−/TetO-Cretg/−/β-cateninfl/fl (Mucenski et al., 2003), β-cateninΔ(ex3) (Mucenski et al., 2005), SPC-rtTAtg/−/TetO-KrasG12D (Fisher et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2012), SPC-rtTAtg/−/TetO-KrasG12D/TetO-Cretg/−/Foxm1fl/fl (Wang et al., 2012), SPC-rtTAtg/−/TetO-GFP-Foxm1-delN (Wang et al., 2010); SPC-rtTAtg/−/TetO-GFP-Foxm1-delN/TOPGAL (Wang et al., 2012) and SPC-rtTAtg/−/TetO-Cretg/−/Sox9fl/fl (Perl et al., 2005). To activate transgenes in respiratory epithelium, Doxycycline (Dox) was given to dams in food (625 mg/kg; Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) from E0.5 until the embryo harvest at E12.5, E14.5 or E16.5.

H&E and immunostaining

4% formalin-fixed and paraffin-embeded mouse lung tissue samples were cut into 5μm thick sections and used for H&E or immunofluorescent staining as described (Kalinichenko et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2005b; Malin et al., 2007; Ren et al., 2010; Ren et al., 2014). The following antibodies were used for immunostaining: SOX9 (AB5535, Millipore and AF3075, R&D Systems), SOX2 (Ustiyan et al., 2012), β-catenin (sc-1496, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), TTF1 (Nkx2.1) (R1231, Seven Hills Bioreagents), T1α (Kalin et al., 2008b); p63 (sc71827, Santa Cruz Biotechnology); cyclin D1 (ab7958, abcam); cytokeratin 5 (a gift from J. Whitsett, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital) and β-galactosidase (Ustiyan et al., 2012). Immunostaining for β-galactosidase was performed as described (Kalinichenko et al., 2003).

For co-localization experiments, secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488, Alexa Fluor 594 or Alexa Fluor 647 (Invitrogen and Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) were used as previously described (Ustiyan et al., 2009; Balli et al., 2011; Ustiyan et al., 2012). Slides were counterstained with DAPI (Vector Laboratory). Fluorescent images were taken using a Zeiss Axioplan2 microscope equipped with an AxioCam MRm digital camera and AxioVision 4.8.2.0 Software (Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Thornwood, NY) as described (Kalin et al., 2008a; Ustiyan et al., 2012; Ren et al., 2013; Bolte et al., 2015).

Statistical analysis

Student’s T-test was used to determine statistical significance. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant. Values for all measurements were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Bullet Points.

-

-

β-Catenin Stimulate Sox9 in Peripheral Lung Epithelial Progenitors.

-

-

β-Catenin Restrict Sox9 in Basal Cells.

-

-

Kras stimulates Sox9 in Basal Cells via Foxm1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Craig Bolte for helpful comments and Ann Maher for editorial assistance.

Grant Support: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL84151 and HL123490 (both to V. V. K.).

References

- Balli D, Ren X, Chou FS, Cross E, Zhang Y, Kalinichenko VV, Kalin TV. Foxm1 transcription factor is required for macrophage migration during lung inflammation and tumor formation. Oncogene. 2012;31:3875–3888. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balli D, Zhang Y, Snyder J, Kalinichenko VV, Kalin TV. Endothelial Cell-Specific Deletion of Transcription Factor FoxM1 Increases Urethane-Induced Lung Carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:40–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blache P, van de Wetering M, Duluc I, Domon C, Berta P, Freund JN, Clevers H, Jay P. SOX9 is an intestine crypt transcription factor, is regulated by the Wnt pathway, and represses the CDX2 and MUC2 genes. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:37–47. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200311021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolte C, Ren X, Tomley T, Ustiyan V, Pradhan A, Hoggatt A, Kalin TV, Herring BP, Kalinichenko VV. Forkhead box F2 regulation of platelet-derived growth factor and myocardin/serum response factor signaling is essential for intestinal development. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:7563–7575. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.609487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolte C, Zhang Y, Wang IC, Kalin TV, Molkentin JD, Kalinichenko VV. Expression of Foxm1 transcription factor in cardiomyocytes is required for myocardial development. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolte C, Zhang Y, York A, Kalin TV, Schultz Jel J, Molkentin JD, Kalinichenko VV. Postnatal ablation of Foxm1 from cardiomyocytes causes late onset cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis without exacerbating pressure overload-induced cardiac remodeling. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48713. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaccione KM, Hong X, Morgan KM, Liu W, Bishop JM, Liu L, Markert E, Deen M, Minerowicz C, Bertino JR, Allen T, Pine SR. Sox9 mediates Notch1-induced mesenchymal features in lung adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2014;5:3636–3650. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso WV. Molecular regulation of lung development. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:471–494. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang DR, Martinez Alanis D, Miller RK, Ji H, Akiyama H, McCrea PD, Chen J. Lung epithelial branching program antagonizes alveolar differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:18042–18051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311760110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng XH, Black M, Ustiyan V, Le T, Fulford L, Sridharan A, Medvedovic M, Kalinichenko VV, Whitsett JA, Kalin TV. SPDEF inhibits prostate carcinogenesis by disrupting a positive feedback loop in regulation of the Foxm1 oncogene. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YJ, Song JH, Yoon JH, Choi WS, Nam SW, Lee JY, Park WS. Aberrant expression of SOX9 is associated with gastrokine 1 inactivation in gastric cancers. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17:247–254. doi: 10.1007/s10120-013-0277-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa RH, Kalinichenko VV, Lim L. Transcription Factors in Mouse Lung Development and Function. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280:L823–L838. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.5.L823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher GH, Wellen SL, Klimstra D, Lenczowski JM, Tichelaar JW, Lizak MJ, Whitsett JA, Koretsky A, Varmus HE. Induction and apoptotic regression of lung adenocarcinomas by regulation of a K-Ras transgene in the presence and absence of tumor suppressor genes. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3249–3262. doi: 10.1101/gad.947701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goss AM, Tian Y, Tsukiyama T, Cohen ED, Zhou D, Lu MM, Yamaguchi TP, Morrisey EE. Wnt2/2b and beta-catenin signaling are necessary and sufficient to specify lung progenitors in the foregut. Dev Cell. 2009;17:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto S, Chen H, Que J, Brockway BL, Drake JA, Snyder JC, Randell SH, Stripp BR. beta-Catenin-SOX2 signaling regulates the fate of developing airway epithelium. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:932–942. doi: 10.1242/jcs.092734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan BL, Yingling JM. Epithelial/mesenchymal interactions and branching morphogenesis of the lung. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:481–486. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalin TV, Meliton L, Meliton AY, Zhu X, Whitsett JA, Kalinichenko VV. Pulmonary mastocytosis and enhanced lung inflammation in mice heterozygous null for the Foxf1 gene. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008a;39:390–399. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0044OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalin TV, Wang IC, Meliton L, Zhang Y, Wert SE, Ren X, Snyder J, Bell SM, Graf L, Jr, Whitsett JA, Kalinichenko VV. Forkhead Box m1 transcription factor is required for perinatal lung function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008b;105:19330–19335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806748105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinichenko VV, Gusarova GA, Shin B, Costa R. The Forkhead Box F1 Transcription Factor is Expressed in Brain and Head Mesenchyme during Mouse Embryonic Development. Gene Expression Patterns. 2003;3:153–158. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(03)00010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinichenko VV, Lim L, Beer-Stoltz D, Shin B, Rausa FM, Clark J, Whitsett JA, Watkins SC, Costa RH. Defects in Pulmonary Vasculature and Perinatal Lung Hemorrhage in Mice Heterozygous Null for the Forkhead Box f1 transcription factor. Dev Biol. 2001;235:489–506. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinichenko VV, Zhou Y, Shin B, Beer-Stoltz D, Watkins SC, A WJ, Costa RH. Wild Type Levels of the Mouse Forkhead Box f1 Gene are Essential for Lung Repair. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282:L1253–L1265. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00463.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamachi Y, Uchikawa M, Kondoh H. Pairing SOX off: with partners in the regulation of embryonic development. Trends Genet. 2000;16:182–187. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01955-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim IM, Ramakrishna S, Gusarova GA, Yoder HM, Costa RH, Kalinichenko VV. The forkhead box M1 transcription factor is essential for embryonic development of pulmonary vasculature. J Biol Chem. 2005a;280:22278–22286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500936200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim IM, Zhou Y, Ramakrishna S, Hughes DE, Solway J, Costa RH, Kalinichenko VV. Functional characterization of evolutionary conserved DNA regions in forkhead box f1 gene locus. J Biol Chem. 2005b;280:37908–37916. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506531200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kling DE, Lorenzo HK, Trbovich AM, Kinane TB, Donahoe PK, Schnitzer JJ. MEK-1/2 inhibition reduces branching morphogenesis and causes mesenchymal cell apoptosis in fetal rat lungs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282:L370–L378. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00200.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Li A, Li M, Xing Y, Chen H, Hu L, Tiozzo C, Anderson S, Taketo MM, Minoo P. Stabilized beta-catenin in lung epithelial cells changes cell fate and leads to tracheal and bronchial polyposis. Dev Biol. 2009;334:97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Liu Z, Jiang B, Peng R, Ma Z, Lu J. SOX9 Overexpression Promotes Glioma Metastasis via Wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s12013-015-0647-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma RY, Tong TH, Cheung AM, Tsang AC, Leung WY, Yao KM. Raf/MEK/MAPK signaling stimulates the nuclear translocation and transactivating activity of FOXM1c. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:795–806. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major ML, Lepe R, Costa RH. Forkhead Box M1B (FoxM1B) Transcriptional Activity Requires Binding of Cdk/Cyclin Complexes for Phosphorylation-Dependent Recruitment of p300/CBP Co-activators. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:2649–2661. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.7.2649-2661.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malin D, Kim IM, Boetticher E, Kalin TV, Ramakrishna S, Meliton L, Ustiyan V, Zhu X, Kalinichenko VV. Forkhead box F1 is essential for migration of mesenchymal cells and directly induces integrin-beta3 expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:2486–2498. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01736-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrisey EE, Hogan BL. Preparing for the first breath: genetic and cellular mechanisms in lung development. Dev Cell. 2010;18:8–23. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucenski ML, Nation JM, Thitoff AR, Besnard V, Xu Y, Wert SE, Harada N, Taketo MM, Stahlman MT, Whitsett JA. Beta-catenin regulates differentiation of respiratory epithelial cells in vivo. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L971–L979. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00172.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucenski ML, Wert SE, Nation JM, Loudy DE, Huelsken J, Birchmeier W, Morrisey EE, Whitsett JA. beta-Catenin is required for specification of proximal/distal cell fate during lung morphogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40231–40238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305892200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okubo T, Hogan BL. Hyperactive Wnt signaling changes the developmental potential of embryonic lung endoderm. J Biol. 2004;3:11. doi: 10.1186/jbiol3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco-Pinedo EC, Durham AC, Stewart KM, Goss AM, Lu MM, Demayo FJ, Morrisey EE. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling accelerates mouse lung tumorigenesis by imposing an embryonic distal progenitor phenotype on lung epithelium. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1935–1945. doi: 10.1172/JCI44871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perl AK, Kist R, Shan Z, Scherer G, Whitsett JA. Normal lung development and function after Sox9 inactivation in the respiratory epithelium. Genesis. 2005;41:23–32. doi: 10.1002/gene.20093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perl AK, Wert SE, Nagy A, Lobe CG, Whitsett JA. Early restriction of peripheral and proximal cell lineages during formation of the lung. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10482–10487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152238499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchett J, Athwal V, Roberts N, Hanley NA, Hanley KP. Understanding the role of SOX9 in acquired diseases: lessons from development. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17:166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlins EL. The building blocks of mammalian lung development. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:463–476. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlins EL, Okubo T, Xue Y, Brass DM, Auten RL, Hasegawa H, Wang F, Hogan BL. The role of Scgb1a1+ Clara cells in the long-term maintenance and repair of lung airway, but not alveolar, epithelium. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:525–534. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X, Shah TA, Ustiyan V, Zhang Y, Shinn J, Chen G, Whitsett JA, Kalin TV, Kalinichenko VV. FOXM1 promotes allergen-induced goblet cell metaplasia and pulmonary inflammation. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:371–386. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00934-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X, Ustiyan V, Pradhan A, Cai Y, Havrilak JA, Bolte CS, Shannon JM, Kalin TV, Kalinichenko VV. FOXF1 Transcription Factor Is Required for Formation of Embryonic Vasculature by Regulating VEGF Signaling in Endothelial Cells. Circ Res. 2014 doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.304382. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X, Zhang Y, Snyder J, Cross ER, Shah TA, Kalin TV, Kalinichenko VV. Forkhead box M1 transcription factor is required for macrophage recruitment during liver repair. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:5381–5393. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00876-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock JR, Onaitis MW, Rawlins EL, Lu Y, Clark CP, Xue Y, Randell SH, Hogan BL. Basal cells as stem cells of the mouse trachea and human airway epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:12771–12775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906850106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockich BE, Hrycaj SM, Shih HP, Nagy MS, Ferguson MA, Kopp JL, Sander M, Wellik DM, Spence JR. Sox9 plays multiple roles in the lung epithelium during branching morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E4456–E4464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311847110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar A, Hochedlinger K. The sox family of transcription factors: versatile regulators of stem and progenitor cell fate. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta A, Kalinichenko VV, Yutzey KE. FoxO1 and FoxM1 Transcription Factors Have Antagonistic Functions in Neonatal Cardiomyocyte Cell-Cycle Withdrawal and IGF1 Gene Regulation. Circ Res. 2013;112:267–277. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.277442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw AT, Meissner A, Dowdle JA, Crowley D, Magendantz M, Ouyang C, Parisi T, Rajagopal J, Blank LJ, Bronson RT, Stone JR, Tuveson DA, Jaenisch R, Jacks T. Sprouty-2 regulates oncogenic K-ras in lung development and tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2007;21:694–707. doi: 10.1101/gad.1526207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topol L, Chen W, Song H, Day TF, Yang Y. Sox9 inhibits Wnt signaling by promoting beta-catenin phosphorylation in the nucleus. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:3323–3333. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808048200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turcatel G, Rubin N, Menke DB, Martin G, Shi W, Warburton D. Lung mesenchymal expression of Sox9 plays a critical role in tracheal development. BMC Biol. 2013;11:117. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-11-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ustiyan V, Wang IC, Ren X, Zhang Y, Snyder J, Xu Y, Wert SE, Lessard JL, Kalin TV, Kalinichenko VV. Forkhead box M1 transcriptional factor is required for smooth muscle cells during embryonic development of blood vessels and esophagus. Dev Biol. 2009;336:266–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ustiyan V, Wert SE, Ikegami M, Wang IC, Kalin TV, Whitsett JA, Kalinichenko VV. Foxm1 transcription factor is critical for proliferation and differentiation of Clara cells during development of conducting airways. Dev Biol. 2012;370:198–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volckaert T, Campbell A, Dill E, Li C, Minoo P, De Langhe S. Localized Fgf10 expression is not required for lung branching morphogenesis but prevents differentiation of epithelial progenitors. Development. 2013;140:3731–3742. doi: 10.1242/dev.096560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, He L, Ma F, Regan MM, Balk SP, Richardson AL, Yuan X. SOX9 regulates low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 (LRP6) and T-cell factor 4 (TCF4) expression and Wnt/beta-catenin activation in breast cancer. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:6478–6487. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.419184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang IC, Snyder J, Zhang Y, Lander J, Nakafuku Y, Lin J, Chen G, Kalin TV, Whitsett JA, Kalinichenko VV. Foxm1 Mediates Cross Talk between Kras/Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase and Canonical Wnt Pathways during Development of Respiratory Epithelium. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:3838–3850. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00355-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang IC, Ustiyan V, Zhang Y, Cai Y, Kalin TV, Kalinichenko VV. Foxm1 transcription factor is required for the initiation of lung tumorigenesis by oncogenic Kras(G12D.) Oncogene. 2014;33:5391–5396. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang IC, Zhang Y, Snyder J, Sutherland MJ, Burhans MS, Shannon JM, Park HJ, Whitsett JA, Kalinichenko VV. Increased expression of FoxM1 transcription factor in respiratory epithelium inhibits lung sacculation and causes Clara cell hyperplasia. Dev Biol. 2010;347:301–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton D, El-Hashash A, Carraro G, Tiozzo C, Sala F, Rogers O, De Langhe S, Kemp PJ, Riccardi D, Torday J, Bellusci S, Shi W, Lubkin SR, Jesudason E. Lung organogenesis. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2010;90:73–158. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)90003-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton D, Zhao J, Berberich MA, Bernfield M. Molecular embryology of the lung: then now**in the future. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:L697–L704. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.5.L697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitsett JA, Wert SE, Trapnell BC. Genetic disorders influencing lung formation and function at birth. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(2):R207–R215. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia H, Ren X, Bolte CS, Ustiyan V, Zhang Y, Shah TA, Kalin TV, Whitsett JA, Kalinichenko VV. Foxm1 regulates resolution of hyperoxic lung injury in newborns. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2015;52:611–621. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0091OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]