Abstract

Background: Close contact with asymptomatic children younger than three years is a risk factor for a primary cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. In pregnant women, such primary infection increases the risk of CMV-induced feto- or embryopathy. Daycare providers have therefore implemented working restrictions for pregnant daycare workers (DCWs) in accordance with legislation and guidelines for maternity protection. However, little is known about the infection risk for DCWs. We therefore compared the prevalence of CMV antibodies of pregnant DCWs to that of female blood donors (BDs).

Method: In a secondary data analysis, the prevalence of anti-CMV IgG among pregnant DCWs (N=509) in daycare centers (DCCs) was compared to the prevalence of female first-time BDs (N=14,358) from the greater region of Hamburg, Germany. Data collection took place between 2010 and 2013. The influence of other risk factors such as age, pregnancies and place of residence was evaluated using logistic regression models.

Results: The prevalence of CMV antibodies in pregnant DCWs was higher than in female BDs (54.6 vs 41.5%; OR 1.6; 95%CI 1.3–1.9). The subgroup of BDs who had given birth to at least one child and who lived in the city of Hamburg (N=2,591) had a prevalence of CMV antibodies similar to the prevalence in pregnant DCWs (53.9 vs 54.6%; OR 0.9; 95%CI 0.8–1.2). Age, pregnancy history and living in the center of Hamburg were risk factors for CMV infections.

Conclusion: The comparison of pregnant DCWs to the best-matching subgroup of female first-time BDs with past pregnancies and living in the city of Hamburg does not indicate an elevated risk of CMV infection among DCWs. However, as two secondary data sets from convenience samples were used, a more detailed investigation of the risk factors other than place of residence, age and maternity was not possible. Therefore, the CMV infection risk in DCWs should be further studied by taking into consideration the potential preventive effect of hygiene measures.

Keywords: daycare workers (DCWs), daycare providers, nursery educators, CMV infection, female blood donors

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund: Enger Kontakt zu asymptomatischen Kindern unter drei Jahren gilt als Risikofaktor für eine primäre Cytomegalievirus (CMV)-Infektion. Eine Primärinfektion während der Schwangerschaft kann zu einer CMV bedingten Feto- und Embryopathie führen. In Übereinstimmung mit dem Mutterschutzgesetz gibt es daher Tätigkeitsbeschränkungen für schwangere Erzieherinnen in Kindertagesstätten (KiTa), die Anti-CMV negativ sind. Bisher ist jedoch wenig über das tatsächliche Infektionsrisiko in KiTas bekannt. Wir haben deshalb die Prävalenz von CMV-Antikörpern bei schwangeren Erzieherinnen mit derjenigen von Blutspenderinnen verglichen.

Methoden: In einer Gelegenheitsdatenanalyse wurde die Prävalenz von Anti-CMV IgG bei schwangeren Erzieherinnen von KiTas (N=509) mit derjenigen von neuen Blutspenderinnen (n=14,358) aus Hamburg und Umgebung verglichen. Die Daten wurden zwischen 2010 und 2013 erhoben. Der Einfluss anderer Risikofaktoren wie Alter, Schwangerschaft und Wohnort wurde mittels logistischer Regression überprüft.

Ergebnisse: Schwangere Erzieherinnen hatten eine höhere CMV-Antikörper-Prävalenz als Blutspenderinnen (54,6 vs. 41,5%; OR 1,6; 95%CI 1,3–1.9). Blutspenderinnen mit mindestens einem Kind und Wohnort in Hamburg (n=2,591) hatten eine ähnlich hohe Prävalenz wie die Erzieherinnen (53,9 vs. 54,6%; OR 0,9; 95%CI 0,8–1.2). Alter, Schwangerschaften und Wohnort in Hamburg waren Risikofaktoren für eine CMV-Infektion.

Schlussfolgerungen: Der Vergleich mit der wahrscheinlich am besten geeigneten Gruppe ergab kein erhöhtes Risiko für CMV-Infektionen bei Erzieherinnen in KiTas. Da jedoch lediglich Gelegenheitsdaten für die sekundäre Datenanalyse verwendet wurden, sollte das Infektionsrisiko für Erzieherinnen unter Berücksichtigung von möglichen Risikofaktoren genauer untersucht werden. Ferner sollte der protektive Effekt von Präventionsmaßnahmen untersucht werden.

Background

A primary cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection during pregnancy increases the risk of congenital anomalies, while this risk seems to be minor for secondary infections during pregnancy [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]. Infections occur in all age groups [9]. CMV enters latency following primary infection and can subsequently reactivate. Reinfection with a different viral strain can also occur. As CMV is shed in bodily fluids, risk factors for transmission are intimate contact, being breastfed, care of small children, as well as low educational level, hygienic and socioeconomic standards [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]. Why is contact with little children a key risk factor? Half of breastfeeding mothers are healthy CMV carriers and share the viruses with their babies via lactation. Approximately one-third of breastfed children become asymptomatic CMV carriers themselves for months or years with the potential to infect or reinfect others.

Based on the German Maternity Protection Law (Mutterschutzgesetz), German guidelines on maternity protection therefore demand restrictions concerning work for pregnant anti-CMV-negative daycare workers (DCWs). In order to protect DCWs from primary infection, their CMV serostatus must be checked at the beginning of their pregnancy. When the DCW is seronegative, she is excluded from professional activities with children under the age of three years in order to prevent feto- or embryopathy in her offspring. Given the shortage of DCWs, these restrictions might pose problems for some daycare centers (DCCs). As studies on CMV infection rates in DCWs are lacking, we analyzed data relating to pregnant DCWs and blood donors (BDs) in the same geographical region to provide an initial overview of the prevalence of CMV infections in DCWs in comparison with the general population.

Methods

We examined two anonymized data sets. The first data set comprised pregnant DCWs (N=517) living in Hamburg, and the second data set comprised female first-time BDs (N=16,286). Both samples were collected between 2010 and 2013 in the geographical region of the city of Hamburg, Germany, and its surrounding districts. Information included date of birth, date of blood sample, and gender. Information about pregnancies and place of work or residence differed in both samples. In contrast to the DCWs, BDs were not knowingly pregnant at the time of sampling, but had a medical record with information about past pregnancies. Furthermore, place of residence was determined by postal codes. In both groups – DCWs and BDs – specific immunoglobulin antibodies (anti-CMV IgG) were analyzed using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Seropositivity was defined as the stable presence of anti-CMV IgG.

Data relating to DCWs came from the State Institute for Food Safety, Health and Environment, Hamburg. The blood samples were taken during a medical examination by a company doctor at the beginning of the pregnancy. This dataset contained information on place of work, age, and CMV serostatus. The data was double-checked by the company doctor to verify the identity of participants with identical dates of birth. If a DCW was examined twice, only the results related to the first pregnancy were considered. The analysis was limited to female DCWs younger than 45 years of age, as only eight DCWs were older than 45 years. The test results of 509 DCWs were therefore analyzed.

The dataset comprising BDs was provided by the Central Institute for Transfusion Medicine, Hamburg. Originally, it included the results of CMV IgG tests of 16,286 first-time BDs, age, information about past pregnancies (“Have you ever been pregnant?”) and place of current residence specified by postal code. Occupation was documented in a non-standardized way; therefore we refrained from including it in our analysis. We excluded 16 cases due to a lack of data on CM serostatus, and eleven cases due to a lack of information on pregnancies. Furthermore, in order to enable better comparability, 1,901 cases were excluded because they were older than 45 years. The test results of 14,358 female BDs were thus analyzed.

We examined the relevance of region of residence as a proxy of socioeconomic status (SES). Residence in the city (post codes 20–22) is assumed to be associated with lower SES. We analyzed the data using the following groups:

BD – Blood donors

BDPcity – Blood donors with pregnancy, living in the city

Statistical analyses

Differences between the two groups were examined using contingency table analyses with Pearson’s chi-square test. For ordinal data, the proportions of anti-CMV IgG test results were compared using the chi-square test for trend. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. Adjusted odds ratios (OR) for anti-CMV IgG test results depending on the available putative risk factors were calculated using logistic regression. A backwards stepwise method was applied for model building using the change criterion [15].

Ethical consideration

In accordance with the Professional Code for Physicians in Hamburg (Art. 15, 1., as of 10.03.2014) and the Chamber Legislation for Medical Professions in the Federal State of Hamburg (HmbKGH), it is only necessary to obtain advice on questions of professional ethics and professional conduct from an Ethics Committee if data which can be traced to a particular individual are used in a research project. Laboratory data were collected routinely. Both datasets were made available to the research center in an anonymized format. Therefore, no ethical approval was obtained.

Results

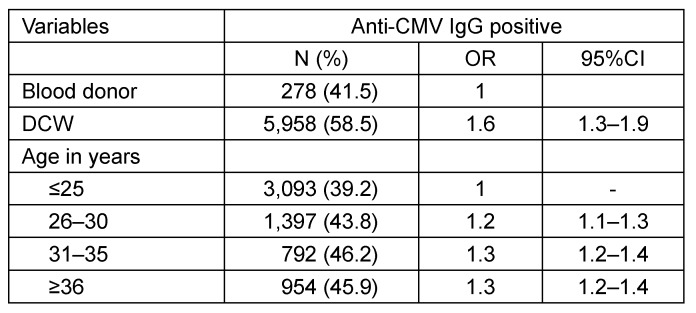

A total of 509 pregnant DCWs and 14,358 female first-time BDs were eligible for the analysis. The characteristics of both samples are listed in Table 1 (Tab. 1). The DCWs were older than the BDs (mean age 30.7 [SD 4.7] vs 26.6 [SD 7.2]; p<0.001). In particular, BDs were more often younger than 25 years (54.5 vs 12.4%). The majority of BDs resided in the city of Hamburg (94%). They significantly more often tested positive for anti-CMV IgG than those who lived in the surrounding region (42.0 vs 34.2%; p<0.001; Table 2 (Tab. 2)). Around 19.4% of BDs had been pregnant at least once (Table 1 (Tab. 1)). BDs with a history of pregnancy significantly more often tested positive for anti-CMV IgG than those without (53.1 vs 38.7%; p<0.001; Table 2 (Tab. 2)). Compared to the youngest age group, the prevalence of CMV antibodies was slightly increased in all other age groups; however, no clear increase across the different age groups was apparent in the combined dataset (OR between 1.2 and 1.3; Table 3 (Tab. 3)).

Table 1. Characteristics of DCWs and BDs.

Table 2. Adjusted odds ratios for anti-CMV IgG positivity by age, pregnancy, and place of residence among BDs.

Table 3. Adjusted odds ratios for anti-CMV IgG positivity depending on status as DCW and on age.

Compared to BDs as a whole, the prevalence of anti-CMV IgG among female DCWs was significantly higher (41.5 vs 54.6%. The age-adjusted OR was 1.6 (95%CI 1.3–1.9; Table 3 (Tab. 3)). When compared to all BDs, DCWs showed higher positive prevalence rates in all age groups. However, when compared to the BDPcity subgroup, the prevalence rates in the different age groups were similar (Table 4 (Tab. 4)). Therefore, the subgroup comprising BDs with at least one pregnancy in their medical history and residing in the city of Hamburg had a prevalence rate similar to that of DCWs (53.9 vs 54.6%). The age-adjusted OR was 0.9 (95%CI 0.8–1.2) (no table).

Table 4. Anti-CMV IgG of DCWs, BDs, and subgroup (BDPcity) by age.

Discussion

We analyzed anti-CMV IgG seroprevalence datasets from pregnant DCWs and female BDs in the same region. The results for both groups were in the range of prevalence rates reported for European populations [9], [12]. As assumed, DCWs had a higher anti-CMV IgG prevalence than did the female BDs. BDs living in the metropolitan region of Hamburg had a higher CMV prevalence than BDs who lived in the wealthier suburbs of Hamburg (BDS). Our results therefore confirm the relevance of socioeconomic factors (SES) previously described by other authors [13].

However, when comparing DCWs with the best-matching subgroup of female BDs (BDPcity) with at least one pregnancy and residing in the city of Hamburg, no significant difference in prevalence was found, contradicting the hypothesis of an increasing risk during working life.

It is likely that anti-CMV IgG among pregnant DCWs is underestimated in our study because the specific IgG was only tested for DCWs with unknown or negative tests in their medical history. Furthermore, there was no information on the migration background (yes/no) of participants in either group. The dataset of DCWs working in Hamburg did not include information about the presence of children in the household or the postal code of current residence. Both datasets (DCWs and BDs) were convenience samples used for this secondary analysis; we therefore could not systematically examine risk factors such as private contact with young children, number of children in the household, or migrant status.

Depending on the region and social background, the anti-CMV prevalence in adults ranges from 45 to 100% [16], [17], [18], [19]. Adler [20] observed a higher risk for DCWs who cared for children under two years of age compared to DCWs in charge of older children (SP 46 vs 35%; RR 1.29; 95%CI 1.05–1.57; p<0.02). DCWs had a significantly higher risk for seroconversion than did female hospital employees (RR 5.0; 95%CI 2.4–10.5; p<0.001). Moreover, most of the DNA patterns of isolates shed by children were identical to the patterns of the seroconverting DCWs. Ford-Jones et al. [21] confirmed a higher incidence among employees under the age of 30, working with infants, and changing diapers without using gloves. Infants shed viruses more often than toddlers (21% vs 8%, average 17%). Furthermore, Jones et al. [22] reported null CMV seroconversion but a higher seropositivity in DCWs in daycare centers for children with normal development than staff in centers for the developmentally delayed (60 vs 42%; p<0.05), depending on the SES of the children there and corresponding negative viral shedding rates (0 to 38%). Murph et al. [23] associated poor hygiene practices and new CMV shedding in children with a higher infection rate for DCWs (0 to 22% by 12 months; average 7.9%). Bale et al. [24] also described caring for children aged 1 to 2 years (p=0.02) as the strongest predictor of seropositivity. Summarizing the above-mentioned studies, Hyde et al. [19] reported a CMV seroconversion rate from 0 to 12.5% for North American DCWs until 1996 (summary annual infection rate = 8.5%; 95%CI 6.1–11.6%).

Pass et al. [25] were the first to observe a higher CMV risk for DCWs associated with employment or the demographic variable “contact with children younger than three years of age for at least 20 hours per week”. In Canada, Soto et al. [26] described a much higher seroconversion rate in a convenience sample of DCWs working with children younger than three years compared with other DCWs (50 vs 8%). Jackson et al. [27] found that only non-white ethnicities (OR 2.4; 95%CI 1.2–5.0; p=0.01), changing diapers three or more times per week (OR 1.8; 95%CI 1.1–2.8; p=0.02), and having a child living in the household (OR 1.8; 95%CI 1.1–2.9; p=0.01) had a significant impact. The evidence described above was summarized in five reviews [19], [28], [29], [30], [31] relating to nine US/Canadian papers [21], [20], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27]. In addition, Joseph et al. [32] observed an elevated occupational risk at a child-to-educator ratio of more than six children of 18 to 35 months of age (OR 1.87; 95%CI 1.25–2.81). However, the occupational risk was lower than the personal risk of having two or more children of one’s own (OR 1.98; 95%CI 1.19–3.31). In summary, if the control group consisted of hospital workers who differ in several demographic features, or pregnant women, a comparison of rates would suggest an approximately five- to tenfold increase in the risk of CMV infection for DCWs in North America [25].

Current data revealed a decrease in CMV antibody prevalence [13], [14]. In 2002, a survey from Belgium examined the influence of hygiene measures for nursery school teachers in charge of children older than 2.5 years. The private risk (i.e., number of children at home; OR 2.25) was higher than the occupational risk (OR 1.54) [33]. In a French study, lifestyle factors were found to be as important as the occupational risk of a CMV infection [34]. However, in this study, no clear distinction could be made between those who were only caring for younger children and those DCWs in charge of older ones as well. A study from the Netherlands observed that the first two years of daycare employment posed a higher risk than later years (adjusted OR 3.80; p<0.001) [35]. Another study from the Netherlands showed an association between the country of birth and the prevalence of CMV IgG in DCWs (OR 1.7; 95%CI 1.3–2.3) [36].

Some evidence corroborates the assumption of a predominant risk factor “children under two or three years”. Children in DCCs were therefore examined. Twenty years ago, up to 50% of children attending DCCs shed CMV in Sao Paulo [11]. Recently, a French study found that children in DCCs were more likely to spread CMV than a control group comprising children in medical care (51.7 vs 21.7%) [37]. We did not find any data about CMV shedding rates in children in DCCs in Germany.

Regarding evidence about the impact of personal hygiene, there is a broad consensus that direct contact with urine and saliva from young children must be avoided. Hand hygiene is crucial, as CMV is sensitive to soap and disinfectants [21], [23], [38], [33], [39], [40], [41]. As there is currently no vaccine available, hygiene interventions offer the best protection [17], [42].

Conclusions

Our results show that half of DCWs – especially young women – are still at risk of a primary infection during pregnancy resulting in a risk of congenital CMV infection. Our data do not indicate an occupational risk of CMV infection among pregnant DCWs in Hamburg compared to female BDs. This observation is in line with results of recent studies. In addition, we are not aware of any well-designed studies examining the influence of appropriate hygiene in DCCs on CMV transmission. If it could be shown that hygiene measures effectively prevent CMV transmission to DCWs, it would be possible to relax job restrictions for pregnant DCWs.

Notes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Orlikowsky TW. Clinical Outcome: acute symptoms and sleeping hazards. In: Halwachs-Baumann G, editor. Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection. Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Therapie. Wien: Springer; 2011. pp. 91–106. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-7091-0208-4_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kenneson A, Cannon MJ. Review and meta-analysis of the epidemiology of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Rev Med Virol. 2007 Jul-Aug;17(4):253–276. doi: 10.1002/rmv.535. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/rmv.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boppana SB, Rivera LB, Fowler KB, Mach M, Britt WJ. Intrauterine transmission of cytomegalovirus to infants of women with preconceptional immunity. N Engl J Med. 2001 May;344(18):1366–1371. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441804. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200105033441804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamprecht K, Jahn G. Humanes Cytomegalovirus und kongenitale Infektion. [Human cytomegalovirus and congenital virus infection]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2007 Nov;50(11):1379–1392. doi: 10.1007/s00103-007-0194-x. (Ger). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00103-007-0194-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enders G, Daiminger A, Bäder U, Exler S, Enders M. Intrauterine transmission and clinical outcome of 248 pregnancies with primary cytomegalovirus infection in relation to gestational age. J Clin Virol. 2011 Nov;52(3):244–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.07.005. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goelz R, Hamprecht K. Fetale Infektion mit dem humanen Zytomegalovirus. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 2012;160(12):1216–1220. doi: 10.1007/s00112-012-2728-z. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00112-012-2728-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fowler KB, Stagno S, Pass RF, Britt WJ, Boll TJ, Alford CA. The outcome of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in relation to maternal antibody status. N Engl J Med. 1992 Mar;326(10):663–667. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199203053261003. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199203053261003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Price SM, Bonilla E, Zador P, Levis DM, Kilgo CL, Cannon MJ. Educating women about congenital cytomegalovirus: assessment of health education materials through a web-based survey. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14:144. doi: 10.1186/s12905-014-0144-3. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12905-014-0144-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hecker M, Qiu D, Marquardt K, Bein G, Hackstein H. Continuous cytomegalovirus seroconversion in a large group of healthy blood donors. Vox Sang. 2004 Jan;86(1):41–44. doi: 10.1111/j.0042-9007.2004.00388.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0042-9007.2004.00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adler SP. Cytomegalovirus and child day care: risk factors for maternal infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1991 Aug;10(8):590–594. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199108000-00008. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006454-199108000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Mello AL, Ferreira EC, Vilas Boas LS, Pannuti CS. Cytomegalovirus infection in a day-care center in the municipality of São Paulo. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1996 May-Jun;38(3):165–169. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46651996000300001. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0036-46651996000300001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ludwig A, Hengel H. Epidemiological impact and disease burden of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in Europe. Euro Surveill. 2009 Mar;14(9):26–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enders G, Daiminger A, Lindemann L, Knotek F, Bäder U, Exler S, Enders M. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) seroprevalence in pregnant women, bone marrow donors and adolescents in Germany, 1996-2010. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2012 Aug;201(3):303–309. doi: 10.1007/s00430-012-0232-7. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00430-012-0232-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wujcicka W, Gaj Z, Wilczyński J, Sobala W, Spiewak E, Nowakowska D. Impact of socioeconomic risk factors on the seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus infections in a cohort of pregnant Polish women between 2010 and 2011. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014 Nov;33(11):1951–1958. doi: 10.1007/s10096-014-2170-3. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10096-014-2170-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley & Sons; 2000. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/0471722146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cannon MJ, Schmid DS, Hyde TB. Review of cytomegalovirus seroprevalence and demographic characteristics associated with infection. Rev Med Virol. 2010 Jul;20(4):202–213. doi: 10.1002/rmv.655. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/rmv.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffiths PD. Burden of disease associated with human cytomegalovirus and prospects for elimination by universal immunisation. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012 Oct;12(10):790–798. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70197-4. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70197-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manicklal S, Emery VC, Lazzarotto T, Boppana SB, Gupta RK. The "silent" global burden of congenital cytomegalovirus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013 Jan;26(1):86–102. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00062-12. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00062-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hyde TB, Schmid DS, Cannon MJ. Cytomegalovirus seroconversion rates and risk factors: implications for congenital CMV. Rev Med Virol. 2010 Sep;20(5):311–326. doi: 10.1002/rmv.659. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/rmv.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adler SP. Cytomegalovirus and child day care. Evidence for an increased infection rate among day-care workers. N Engl J Med. 1989 Nov;321(19):1290–1296. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198911093211903. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198911093211903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ford-Jones EL, Kitai I, Davis L, Corey M, Farrell H, Petric M, Kyle I, Beach J, Yaffe B, Kelly E, Ryan G, Gold R. Cytomegalovirus infections in Toronto child-care centers: a prospective study of viral excretion in children and seroconversion among day-care providers. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996 Jun;15(6):507–514. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199606000-00007. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006454-199606000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones LA, Duke-Duncan PM, Yeager AS. Cytomegaloviral infections in infant-toddler centers: centers for the developmentally delayed versus regular day care. J Infect Dis. 1985 May;151(5):953–955. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.5.953. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/infdis/151.5.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murph JR, Baron JC, Brown CK, Ebelhack CL, Bale JF., Jr The occupational risk of cytomegalovirus infection among day-care providers. JAMA. 1991 Feb;265(5):603–608. doi: 10.1001/jama.265.5.603. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.265.5.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bale JF, Jr, Zimmerman B, Dawson JD, Souza IE, Petheram SJ, Murph JR. Cytomegalovirus transmission in child care homes. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999 Jan;153(1):75–79. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.1.75. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.153.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pass RF, Hutto C, Lyon MD, Cloud G. Increased rate of cytomegalovirus infection among day care center workers. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1990 Jul;9(7):465–470. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199007000-00003. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006454-199007000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soto G, Delage G, Vincelette J, Belanger L. Cytomegalovirus Infection as an Occupational Hazard Among Women Employed in Day-Care Centers. Pediatrics. 1994;94(Suppl):1031. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson LA, Stewart LK, Solomon SL, Boase J, Alexander ER, Heath JL, McQuillan GK, Coleman PJ, Stewart JA, Shapiro CN. Risk of infection with hepatitis A, B or C, cytomegalovirus, varicella or measles among child care providers. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996 Jul;15(7):584–589. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199607000-00005. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006454-199607000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reves RR, Pickering LK. Impact of child day care on infectious diseases in adults. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1992 Mar;6(1):239–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dobbins JG, Adler SP, Pass RF, Bale JF, Jr, Grillner L, Stewart JA. The risks and benefits of cytomegalovirus transmission in child day care. Pediatrics. 1994 Dec;94(6 Pt 2):1016–1018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bright KA, Calabro K. Child care workers and workplace hazards in the United States: overview of research and implications for occupational health professionals. Occup Med (Lond) 1999 Sep;49(7):427–437. doi: 10.1093/occmed/49.7.427. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/occmed/49.7.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joseph SA, Béliveau C, Muecke CJ, Rahme E, Soto JC, Flowerdew G, Johnston L, Langille D, Gyorkos TW. Cytomegalovirus as an occupational risk in daycare educators. Paediatr Child Health. 2006 Sep;11(7):401–407. doi: 10.1093/pch/11.7.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joseph SA, Beliveau C, Muecke CJ, Rahme E, Soto JC, Flowerdew G, Johnston L, Langille D, Gyorkos TW. Risk factors for cytomegalovirus seropositivity in a population of day care educators in Montréal, Canada. Occup Med (Lond) 2005 Oct;55(7):564–567. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqi121. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqi121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiss P, De Bacquer D, Sergooris L, De Meester M, VanHoorne M. Cytomegalovirus infection: an occupational hazard to kindergarten teachers working with children aged 2.5-6 years. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2002 Apr-Jun;8(2):79–86. doi: 10.1179/107735202800338966. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1179/107735202800338966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Villemeur AB, Gratacap-Cavallier B, Casey R, Baccard-Longère M, Goirand L, Seigneurin JM, Morand P. Occupational risk for cytomegalovirus, but not for parvovirus B19 in child-care personnel in France. J Infect. 2011 Dec;63(6):457–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.06.012. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stelma FF, Smismans A, Goossens VJ, Bruggeman CA, Hoebe CJ. Occupational risk of human Cytomegalovirus and Parvovirus B19 infection in female day care personnel in the Netherlands; a study based on seroprevalence. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009 Apr;28(4):393–397. doi: 10.1007/s10096-008-0635-y. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10096-008-0635-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Rijckevorsel GG, Bovée LP, Damen M, Sonder GJ, Schim van der Loeff MF, van den Hoek A. Increased seroprevalence of IgG-class antibodies against cytomegalovirus, parvovirus B19, and varicella-zoster virus in women working in child day care. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:475. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-475. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grosjean J, Trapes L, Hantz S, Mengelle C, Virey B, Undreiner F, Messager V, Denis F, Marin B, Alain S. Human cytomegalovirus quantification in toddlers saliva from day care centers and emergency unit: a feasibility study. J Clin Virol. 2014 Nov;61(3):371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.07.020. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2014.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adler SP, Finney JW, Manganello AM, Best AM. Prevention of child-to-mother transmission of cytomegalovirus among pregnant women. J Pediatr. 2004 Oct;145(4):485–491. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.05.041. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vauloup-Fellous C, Picone O, Cordier AG, Parent-du-Châtelet I, Senat MV, Frydman R, Grangeot-Keros L. Does hygiene counseling have an impact on the rate of CMV primary infection during pregnancy? Results of a 3-year prospective study in a French hospital. J Clin Virol. 2009 Dec;46 Suppl 4:S49–S53. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.09.003. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cannon MJ, Davis KF. Washing our hands of the congenital cytomegalovirus disease epidemic. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-70. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-5-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.CDC.gov [homepage of the Internet] Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); 2010. [updated 2010 Jul 28; cited 2014 Jun 6]. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Congenital CMV Infection. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/cmv/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robert Koch-Institut (RKI) RKI-Ratgeber für Ärzte: Zytomegalievirus-Infektion. Epidemiol Bull. 2014;(3):23–28. Available from: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Infekt/EpidBull/Archiv/2014/Ausgaben/03_14.pdf?__blob=publicationFile. [Google Scholar]