Abstract

Background

To investigate the effect of pectinase-treated Panax ginseng (GINST) in cellular and male subfertility animal models.

Methods

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-induced mouse spermatocyte GC-2spd cells were used as an in vitro model. Cell viability was measured using MTT assay. For the in vivo study, GINST (200 mg/kg) mixed with a regular pellet diet was administered orally for 4 mo, and the changes in the mRNA and protein expression level of antioxidative and spermatogenic genes in young and aged control rats were compared using real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and western blotting.

Results

GINST treatment (50 μg/mL, 100 μg/mL, and 200 μg/mL) significantly (p < 0.05) inhibited the H2O2-induced (200 μM) cytotoxicity in GC-2spd cells. Furthermore, GINST (50 μg/mL and 100 μg/mL) significantly (p < 0.05) ameliorated the H2O2-induced decrease in the expression level of antioxidant enzymes (peroxiredoxin 3 and 4, glutathione S-transferase m5, and glutathione peroxidase 4), spermatogenesis-related protein such as inhibin-α, and specific sex hormone receptors (androgen receptor, luteinizing hormone receptor, and follicle-stimulating hormone receptor) in GC-2spd cells. Similarly, the altered expression level of the above mentioned genes and of spermatogenesis-related nectin-2 and cAMP response element-binding protein in aged rat testes was ameliorated with GINST (200 mg/kg) treatment. Taken together, GINST attenuated H2O2-induced oxidative stress in GC-2 cells and modulated the expression of antioxidant-related genes and of spermatogenic-related proteins and sex hormone receptors in aged rats.

Conclusion

GINST may be a potential natural agent for the protection against or treatment of oxidative stress-induced male subfertility and aging-induced male subfertility.

Keywords: oxidative enzymes, Panax ginseng, pectinase, spermatogenesis, subfertility

1. Introduction

Ginseng (Panax ginseng Meyer, Araliaceous) is an important medicinal herb that has long been used to treat various diseases in Asian countries [1], [2]. In particular, the major active constituents, ginsenosides, are known to have various physiological activities, such as anti-aging and anti-inflammatory effects, and antioxidant effects in the central nervous system, cardiovascular system, reproductive system, and immune system [1], [3], [4]. It was suggested that P. ginseng has potent effects on sexual function, and could relieve erectile dysfunction [5], senile testicular dysfunction [2], [6], and dioxin-induced testicular damage [7].

It is well known that orally administered ginsenosides are biotransformed by bacteria in the human intestinal lumen, and that the resultant metabolites or enzymatically transformed products have various interesting and strong physiological activities [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]. For example, Rb1, Rb2, and Rc, which are protopanaxadiol-type ginsenosides, are metabolized by human intestinal bacteria to 20-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-20(S)-protopandaxadiol (compound K), while Re and Rg1, protopanaxatriol-type ginsenosides are metabolized into ginsenoside Rh1 or ginsenoside F1 [14], [15], [16], [17]. The metabolites compound K (CK), Rh1, and F1 exhibit various physiological activities, including immune enhancing effects [18], antimetastatic effects, and anticancer effects [19]

Furthermore, the biotransformation of ginsenosides by treatment with enzymes, such as pectinase and rapidase, also proved to be useful for ginsenoside conversion and increased the bioefficiency of ginseng extracts and products [3], [20]. Previous reports revealed that P. ginseng fermentation by lactic acid bacteria generated CK, which is a biotransformation product of Rb1, Rb2, and Rc. Interestingly, CK's cytotoxic effect against tumor cells is much more potent than that of naturally occurring ginsenosides. Pectinase is commonly produced by lactic acid bacteria in the intestines [21], and recent reports have shown that pectinase-treated extracts of P. ginseng (GINST) contain large amounts of CK as well as several other ginsenosides, including Rg3, Rg5, Rk1, Rh1, F2, and Rg2 [22]. Reports also suggested that GINST exhibited various pharmacological effects including antioxidant and antidiabetic activity, the latter exerted by ameliorating hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia in high-fat diet-fed rats [23], [24].

Previously, our group reported that GINST could improve antioxidant status during aging, thereby minimizing oxidative stress and the occurrence of age-related disorders associated with free radicals [3]. Furthermore, we also observed that GINST rescued testicular dysfunction in aged rats [4]. GINST treatment attenuated the morphological changes, number of sperm cells, Sertoli cells, germ cells, and the Sertoli cell index in the testes of aged rats. We also reported that GINST treatment enhanced testicular function by elevating redox-modulating protein activity, thereby increasing glutathione, which prevents lipid peroxidation in the testes of aged rats [4]. However, the intrinsic molecular aspects related to these changes have not yet been studied. In the present study, we evaluated the effect of GINST against hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-induced cytotoxicity in mouse spermatocyte GC-2spd sperm cells, and assessed the oxidative stress-induced changes in the gene expression level of key antioxidant enzymes, spermatogenesis-related proteins, and sex hormone receptors. Furthermore, we evaluated these changes in the gene and protein expression level in aged rats in vivo and compared them with those in young control rats.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. GINST preparation and high-performance liquid chromatography analysis

GINST used in this study was produced from an extract of P. ginseng treated with pectinase as described previously [25]. Briefly, dried ginseng (1 kg) was extracted with 5 L of 50% aqueous liquor at 85°C and was concentrated in vacuo to obtain a dark-brown, viscous solution. The extract was subsequently dissolved in water containing 2.4% pectinase (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA) and was incubated at 55°C for 24 h. The GINST extract was subsequently concentrated in vacuo and the ginsenosides in the extract were analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography as described previously [4].

2.2. Cell culture

Mouse spermatocyte GC-2spd cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). GC-2spd cells, hereinafter referred to as GC-2 cells, were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen Co., Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo-Fisher Inc., Rockford, IL, USA). All media contained 1.2 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 15 mM HEPES, 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin.

2.3. MTT assay

Cell viability was determined using the MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] assay. GC-2 cells were seeded at a density of 1.0 × 104 cells/well in a 96-well plate containing appropriate media for 24 h. The cells were exposed to GINST (50 μg/mL, 100 μg/mL, or 200 μg/mL) for an additional 24 h. The medium was then replaced by MTT (0.4 mg/mL) and the cells were incubated for a further 4 h at 37°C. The purple formazan crystals formed during the reaction were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide. The relative number of viable cells was assessed by measuring the absorbance of the formazan product at 570 nm with a microplate reader (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). H2O2 (Fisher Scientific, Leicestershire, UK) was used as a positive control. To determine the effect of GINST on cell viability in H2O2-exposed cells, the cells were pretreated with GINST at the indicated concentrations (50 μg/mL, 100 μg/mL, and 200 μg/mL) for 24 h prior to exposure to H2O2 (200 μM) for 30 min. Thereafter, cell viability was measured using the MTT assay.

2.4. Experimental animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Samtako Bio Korea, Inc. (Osan, Korea) and were acclimated to the facility for 1 wk prior to the experiment. They were provided with a standard pellet diet and were kept at a constant temperature (23°C ± 2°C) and relative humidity (55 ± 5%) on a 12-/12-h light/dark cycle with access to water ad libitum. The rats were maintained in the Regional Innovation Center Experimental Animal Facility, Konkuk University, Korea, in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee Guidelines. The study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee (Permission No: KU12052) in accordance with article 14 of the Korean Experimental Animal Protection Law.

2.5. Experimental design

The rats were divided into three groups: a young control group [YC: 2-mo-old (280 ± 10 g)], an aged control group [AC; 12-mo-old (750 ± 20 g)], and GINST-treated aged groups [200 mg/kg body weight (b.w.), GINST-AC; 12-mo-old (750 ± 20 g)]. YC (n = 6) and AC (n = 6) received the vehicle (0.9 % saline) only. GINST-AC (n = 6) was administered GINST at a daily dose of 200 mg/kg b.w. for 4 mo. The GINST dose (200 mg/kg b.w.) was based on our previous reported study [4]. GINST was mixed homogeneously with a sterilized standard powder-type diet, which was administered orally after pelletization. The GINST dose was adjusted every 2 wk by taking the b.w. increment and the daily dietary intake into account. At the end of the experimental period, all animals were fasted for 24 h with access to water ad libitum, and were euthanized under general anesthesia with carbon dioxide. The testes were excised, washed in ice cold saline, and cleaned of the adhering fat and connective tissues. A 10% testicular tissue homogenate was prepared in Tris-hydrochloride buffer (0.1M, pH 7.4) and was centrifuged (2,500 rpm for 10 min at 4°C) to pellet the cell debris. The clear supernatant was used for the subsequent assays.

2.6. Western blot analysis

Equal amounts of testis protein from each sample were separated with 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and were transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Each membrane was incubated for 1 h in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 and 5% skimmed milk to block nonspecific antibody binding. The membranes were subsequently incubated with specific primary antibodies (1:2,000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Beta-actin was used as an internal control. Each protein was detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and a chemiluminescence detection system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Little Chalfont, UK).

2.7. RNA isolation and real time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

For the in vitro analysis, GC-2 cells were plated at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well in 12-well plates. After incubation for 1 d, the cells were cultured in the presence of GINST (50 μg/mL and 100 μg/mL) for 2 h, and were stimulated with 200 μM H2O2 (Sigma-Aldrich Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA) for 6 h. Total RNA was extracted from the cells using the RNA-Bee reagent (AMS Bio, Abingdon, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA (1 μg) was reverse-transcribed for 50 min at 37°C in a mixture containing 1 μL oligo (dT), 10 mM deoxynucleotide, 0.1 M dithiothreitol, 5 × polymerase chain reaction (PCR) buffer, and 1 μL Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus Reverse Transcriptase (RT) (Invitrogen Co., Carlsbad, CA, USA). An aliquot (200 ng) of the RT products was amplified in a 25 μL reaction volume using a GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega Co., Madison, WI, USA) in the presence of 10 pM oligonucleotide primer. For the in vivo analysis, total RNA was extracted from the testicular tissue using the RNA-Bee reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the RNA (1 μg) was reverse-transcribed following the procedures as described previously [4]. The following primers were used for the RT products: peroxiredoxin (PRx) 3 (forward sequence, 5′-ACT TTA AGG GAA AAT ACT TGG TGC T-3′; reverse sequence, 5′-TCT CAA AGT ACT CTT TGG AAG CTG T-3′), PRx4 (forward sequence, 5′-CTG ACT GAC TAT CGT GGG AAA TAC T-3′; reverse sequence, 5′-GAT CTG GGA TTA TTG TTT CAC TAC C-3′), glutathione S-transferase (GST) m5 (forward sequence, 5′-TAT GCT CCT GGA GTT TAC TGA TAC C-3′; reverse sequence, 5′-AGA CGT CAT AAG TGA GAA AAT CCA C-3′), glutathione peroxidase (GPx) 4 (forward sequence, 5′-GCA AAA CCG ACG TAA ACT ACA CT-3′; reverse sequence, 5′-CGT TCT TAT CAA TGA GAA ACT TGG T-3′), inhibin-α (forward sequence, 5′-AGG AAG GCC TCT TCA CTT ATG TAT T-3′; reverse sequence, 5′-CTC TTG GAA GGA GAT ATT GAG AGC-3′), androgen receptor (AR) (forward sequence, 5′-CTG GAC TAC CTG GAT CTC TA-3′; reverse sequence, 5′-CCT GGG CTG TAG TTT TAT TG-3′), follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR) (forward sequence, 5′-GGA CTG AGT TTT GAA AGT GT-3′; reverse sequence, 5′-TTC CAT AAC TGG GTT CAT CA-3′), luteinizing hormone receptor (LHR) (forward sequence, 5′-CTA TCT CCC TGT CAA AGT AA-3′; reverse sequence, 5′-TTT GTA CTT CTT CAA ATC CA-3′), nectin-2 (forward sequence, 5′-AGT GAC CTG GCT CAG AGT CA-3′; reverse sequence, 5′-TAG GTA CCA GTT GTC ATC AT-3′), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (forward sequence, 5′-AAC TTT GGC ATT GTG GAA GGG C-3′; reverse sequence, 5′-ACA CAT TGG GGG TAG GAA CAC G-3′). The PCR was performed for 30 cycles at 95°C for 40 s, 56°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 40 s. After amplification, the PCR products were separated using electrophoresis on a 2.0% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide, and the bands were visualized with ultraviolet fluorescence. The intensity of the bands was analyzed using the ImageJ software package (version 1.41o; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MA, USA).

2.8. Statistical analysis

The data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 6). Statistical evaluation of the data was performed using one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and a post hoc test for intergroup comparisons using Tukey's multiple comparison using the GraphPad prism software package (version 4.0; GraphPad, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) for Windows. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

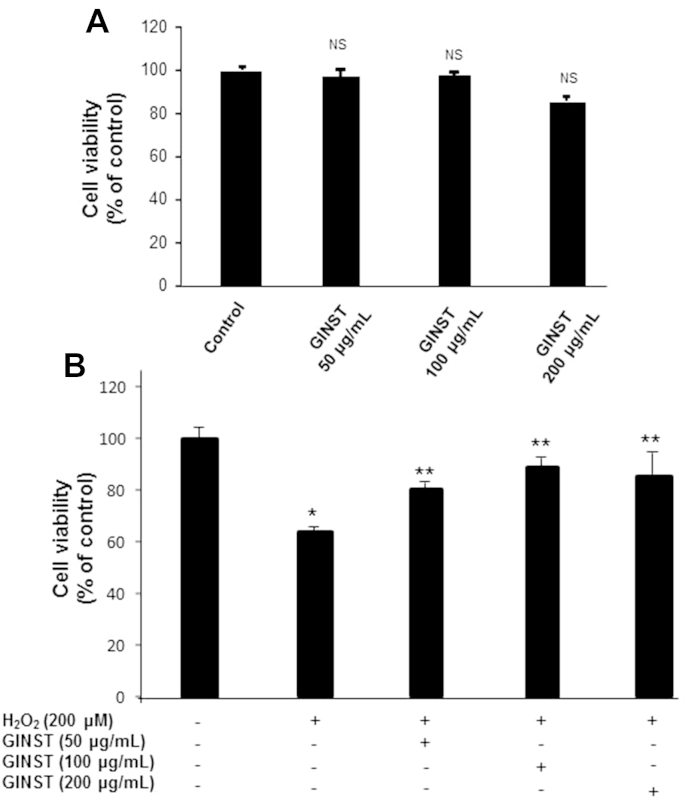

3.1. The effect of GINST on H2O2-induced cytotoxicity in GC-2 cells

As shown in Fig. 1A, treatment with GINST alone at the indicated concentrations (50 μg/mL, 100 μg/mL, and 200 μg/mL) did not show any significant effect on overall cell viability in GC-2 cells. This indicated that the concentrations used in the study were noncytotoxic. In contrast, H2O2-exposed (200 μM) GC-2 cells showed a significant (p < 0.01) decrease in overall cell viability (64.05 ± 0.99%). However, treatment with GINST at the indicated concentrations significantly (p < 0.05) inhibited the H2O2-induced cytotoxicity (Fig. 1B). Although 200 μg/mL GINST showed a significant effect on cell viability, its maximum effect was observed at 100 μg/mL (83.15 ± 0.12%). Therefore, we selected the 50 μg/mL and 100-μg/mL GINST concentrations for the gene expression level experiment.

Fig. 1.

The effect of pectinase-treated Panax ginseng (GINST) on the viability of GC-2 sperm cells. The protocol described in the Materials and methods section 2.2 was followed. Cell viability was evaluated using the MTT assay. (A) The effect of GINST (50 μg/mL, 100 μg/mL, and 200 μg/mL) on the viability of GC-2 cells is shown. (B) The effect of GINST (50 μg/mL, 100 μg/mL, and 200 μg/mL) in GC-2 cells exposed to 200 μM hydrogen peroxide. The results are shown as percentage of the control samples. The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 6). * p < 0.01 compared with the control cells. ** p < 0.05 compared with the hydrogen peroxide-exposed cells as determined with Student t-test and one way analysis of variance using GraphPad Prism version 4.0 for Windows. GINST, pectinase-treated Panax ginseng extract; NS, not significant.

3.2. The effect of GINST on the mRNA expression level of antioxidant enzymes in H2O2-exposed GC-2 cells

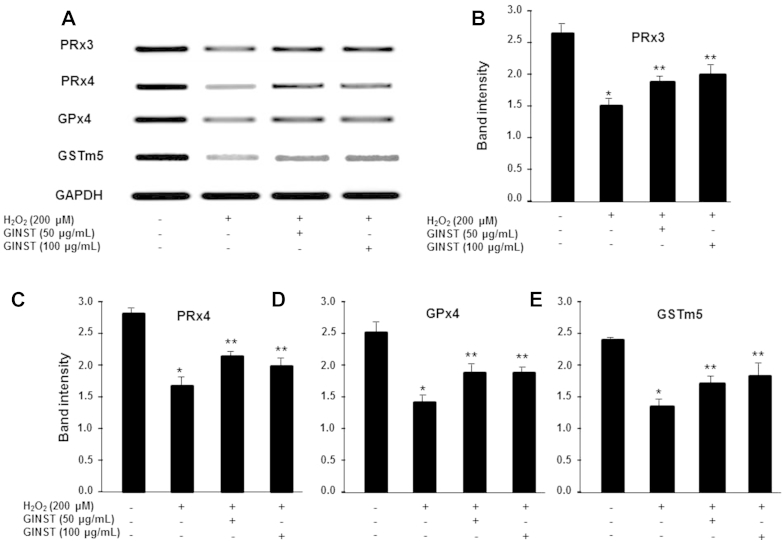

The effect of GINST on the mRNA expression level of the antioxidant enzymes PRx3 and 4, GPx4, and GSTm5 are shown in Fig. 2. H2O2-exposed GC-2 cells showed a decreased PRx3 and 4, GPx4, and GSTm5 expression level compared with that of the control group (Fig. 2A). However, treatment with GINST significantly attenuated this decrease at both concentrations tested (50 μg/mL and 100 μg/mL) as revealed by the PCR product band intensities (Figs. 2B–2E). However, H2O2-exposed GC-2 cells treated with 50 μg/mL GINST showed a slightly more potent decrease in the Prx4 and GPx4 mRNA expression level (Figs. 2C, 2D).

Fig. 2.

The effect of pectinase-treated Panax ginseng extract on the antioxidant enzyme mRNA expression level in hydrogen peroxide-exposed GC-2 cells. The protocol described in the Materials and methods section 2.6 was followed. (A) The mRNA expression level of PRx3 and 4, GPx4, and GSTm5 are shown. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as an internal control. The polymerase chain reaction band intensity of PRx3 (B), PRx4 (C), GPx4 (D), and GSTm5 (E) was analyzed using the ImageJ 1.41o software package and was normalized to that of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 6). * p < 0.01 compared with the control cells. ** p < 0.05 compared with the hydrogen peroxide-exposed cells as determined with Student t-test and one way analysis of variance using GraphPad Prism version 4.0 for Windows. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GINST, pectinase-treated Panax ginseng extract; GPx4, glutathione peroxidase; GSTm5, glutathione S-transferase m5; PRx3 and 4: peroxiredoxin 3 and 4.

3.3. The effect of GINST on the mRNA expression level of spermatogenesis-related proteins in H2O2-exposed GC-2 cells

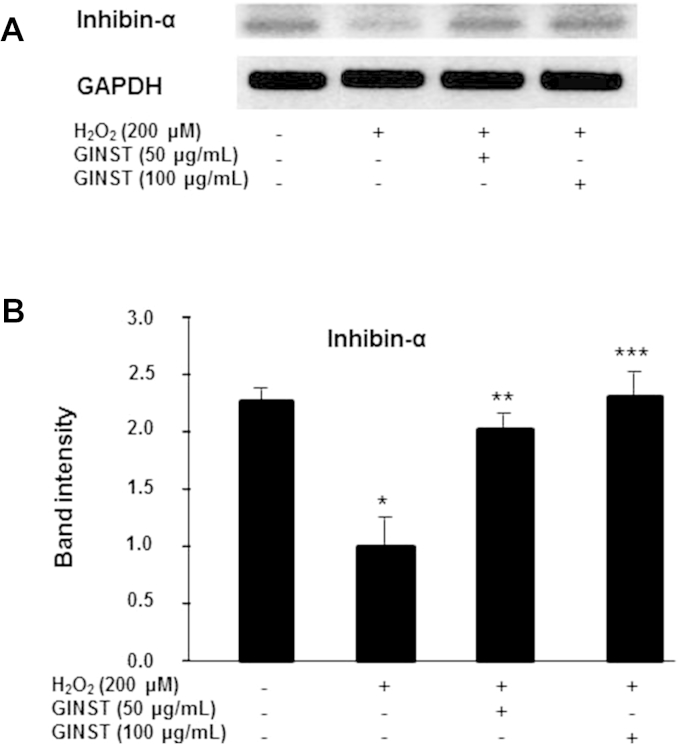

The mRNA expression level of inhibin-α, a key spermatogenesis-related protein, was decreased more than twofold in H2O2-exposed GC-2 cells compared with that in the control cells (p < 0.01) (Fig. 3A). Treatment with GINST at the indicated concentrations (50 μg/mL and 100 μg/mL) significantly (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 at 50 μg/mL and 100 μg/mL, respectively) inhibited this H2O2-induced decrease in inhibin-α expression (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

The effect of pectinase-treated Panax ginseng extract on the inhibin-α mRNA expression level in hydrogen peroxide-exposed GC-2 cells. The protocol described in the Materials and methods section 2.6 was followed. (A) The mRNA expression level of inhibin-α is shown. glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as an internal control. (B) The polymerase chain reaction band intensity of inhibin-α was analyzed using the ImageJ 1.41o software package and was normalized to that of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 6). * p < 0.01 compared with the control cells. ** p < 0.05 compared with the hydrogen peroxide-exposed cells. *** p < 0.01 compared with the hydrogen peroxide-exposed cells as determined with Student t-test and one way analysis of variance using GraphPad Prism version 4.0 for Windows. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GINST, pectinase-treated Panax ginseng extract.

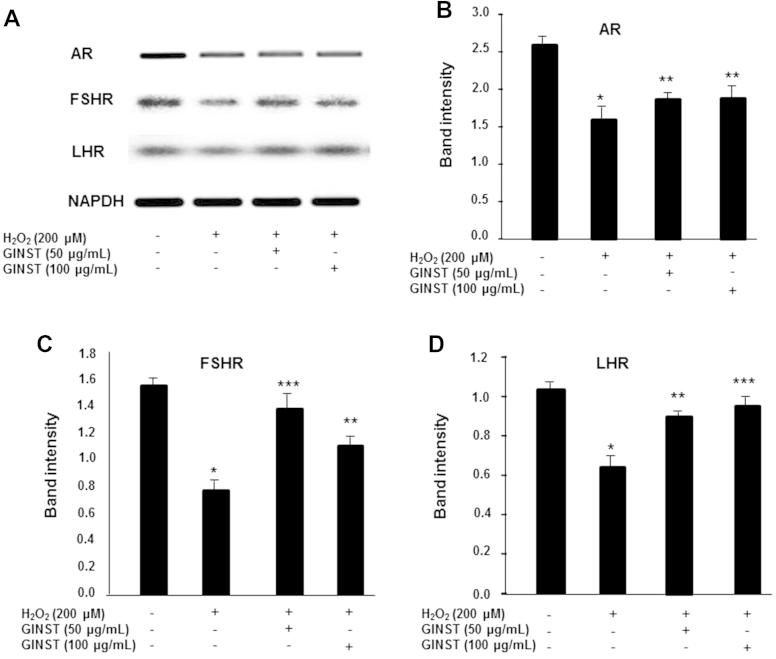

3.4. The effect of GINST on the mRNA expression level of sex hormone receptors in H2O2-exposed GC-2 cells

The mRNA expression level of the sex hormone receptors AR, LHR, and FSHR was significantly (p < 0.01) decreased in H2O2-exposed GC-2 cells (Fig. 4A). GINST treatment at the indicated concentrations (50 μg/mL and 100 μg/mL) significantly (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively) ameliorated this decrease (Figs. 4B–4D).

Fig. 4.

The effect of pectinase-treated Panax ginseng extract on the sex hormone receptor mRNA expression level in hydrogen peroxide-exposed GC-2 cells. The protocol described in the Materials and methods section 2.6 was followed. The mRNA expression level of the androgen receptor, follicle-stimulating hormone receptor, and luteinizing hormone receptor is shown. (A) glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as an internal control. (B) The polymerase chain reaction band intensity of androgen receptor, (C) follicle-stimulating hormone receptor, and (D) luteinizing hormone receptor was analyzed using the ImageJ 1.410 software package and was normalized to that of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 6). * p < 0.01 compared with the control cells. ** p < 0.05. *** p < 0.01 compared with the H2O2-exposed cells as determined the by Student's t-test and one-way ANOVA using GraphPad Prism version 4.0 for Windows. AR, androgen receptor; FSHR, follicle-stimulating hormone receptor; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GINST, pectinase-treated Panax ginseng extract; LHR, luteinizing hormone receptor.

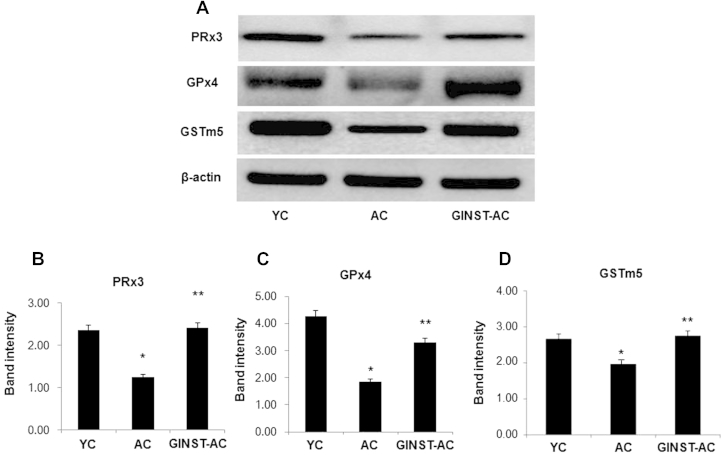

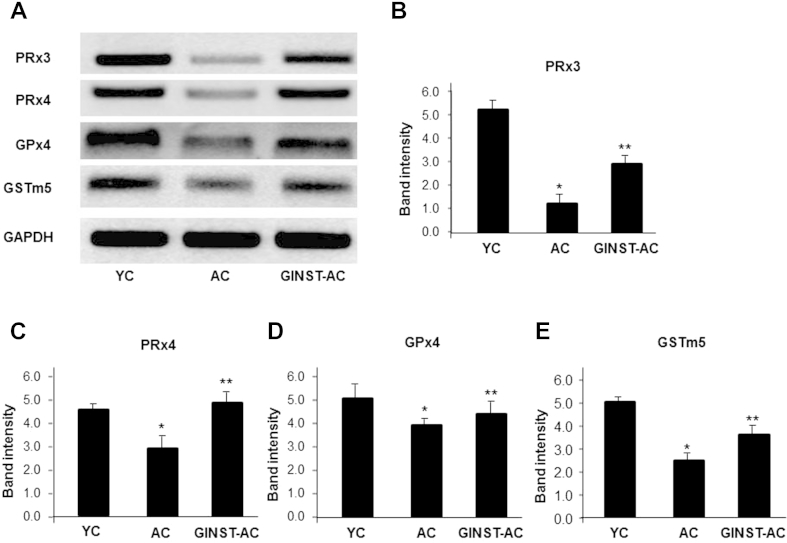

3.5. The effect of GINST on the protein and mRNA expression level of antioxidant enzymes in the testes of aged rats

The testicular protein expression level of PRx3 and 4, GPx4, and GSTm5 significantly (p < 0.01) decreased in the AC group compared with that in the YC group (Fig. 5A). However, this decrease was significantly (p < 0.05) inhibited in the GINST-AC group (Figs. 5B–5D). Similarly, the mRNA expression level of PRx3 and 4, GPx4 and GSTm5 significantly (p < 0.05) decreased in the AC group (Fig. 6A). This decrease was significantly (p < 0.01) ameliorated in the GINST-AC group (Figs. 6B–6E).

Fig. 5.

The effect of pectinase-treated Panax ginseng extract on the testicular antioxidant enzyme protein expression level in young and aged rats. The protocol described in the Materials and methods section 2.4, 2.5 was followed. The protein expression of PRx3 and 4, GPx4, and GSTm5 in testicular tissue was analyzed using western blotting. Tissue lysates from the indicated groups were immunoblotted with specific antibodies. (A) Beta-actin was used as internal control. The protein band intensity of PRx3 (B), GPx4 (C), and GSTm5 (D), respectively, normalized to that of β-actin is shown. The data represent the mean ± standard deviation (n = 6). * p < 0.01 compared with the young control rat group. ** p < 0.05 compared with the aged rat control group as determined with Student t-test and one way analysis of variance using GraphPad Prism version 4.0 for Windows. AC, aged rat control group; GINST, pectinase-treated Panax ginseng extract; GINST-AC, GINST-treated (200 mg/kg body weight.) aged rat group; GSTm5, glutathione S-transferase m5; PRx3 and 4, peroxiredoxin 3 and 4; YC, young control rat group.

Fig. 6.

The effect of pectinase-treated Panax ginseng extract on the testicular antioxidant enzyme mRNA expression level in young and aged rats. The protocol described in the Materials and methods section 2.4, 2.6 was followed. Total RNA was extracted from 50 mg testes tissue of young and aged rats and was reverse-transcribed for 50 min at 37°C. (A) An aliquot (200 ng) of the reverse-transcribed products was amplified and was separated with electrophoresis on a 2.0% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as the internal control. (B–E) The polymerase chain reaction band intensity of PRx3, PRx4, GPx4, and GSTm5, respectively, normalized to that of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase is shown. The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 6). * p < 0.01 compared with the young control rat group. ** p < 0.05 compared with the aged rat control group as determined with Student t-test and one way analysis of variance using GraphPad Prism version 4.0 for Windows. AC, aged rat control group; GINST, pectinase-treated Panax ginseng extract; GINST-AC, GINST-treated (200 mg/kg body weight.) aged rat group; GSTm5, glutathione S-transferase m5; PRx3 and 4, peroxiredoxin 3 and 4; YC, young control rat group.

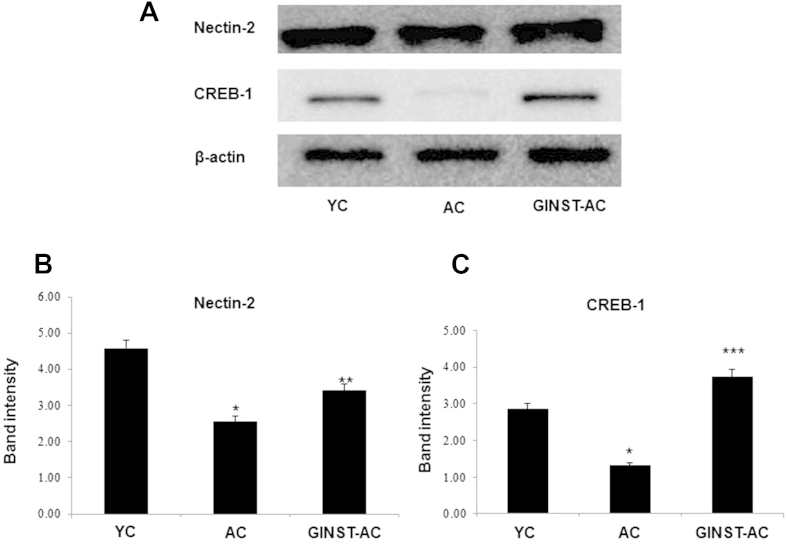

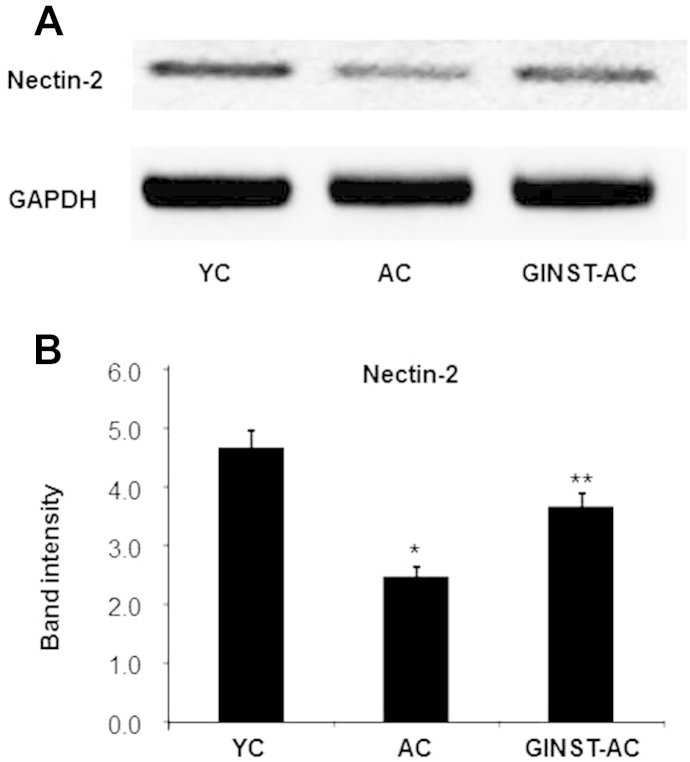

3.6. The effect of GINST on the protein and mRNA expression level of spermatogenesis-related proteins in the testes of aged rats

The testicular protein expression level of nectin-2 and cAMP responsive element binding protein 1 (CREB-1), key proteins related to spermatogenesis, was decreased in the AC group compared with that in the YC group (Fig. 7A), and was ameliorated in the GINST-AC group. In the AC group, the decrease in the testicular protein expression level of CREB-1 was more pronounced than that of nectin-2 (Figs. 7B, 7C). Similarly, the testicular mRNA level of nectin-2 was significantly decreased in the AC group compared with that in the YC group, and was significantly (p < 0.05) ameliorated in the GINST-AC group (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

The effect of pectinase-treated Panax ginseng extract on the testicular protein expression level of key proteins involved in the sex hormone-related spermatogenesis pathway in young and aged rats. The protocol described in the Materials and methods section 2.4, 2.5 was followed. The protein expression level of nectin-2 and cAMP responsive element binding protein in testicular tissue was analyzed using western blotting. (A) Tissue lysates from the indicated groups were immunoblotted with specific antibodies. Beta-actin was used as the internal control. (B, C) The protein band intensity of nectin-2 and cAMP responsive element binding protein, respectively, normalized to β-actin is shown. The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 6). * p < 0.01 compared with the young control rat group. ** p < 0.05 compared with the aged rat control group. *** p < 0.01 compared with the aged rat control group as determined with Student t-test and one way analysis of variance using GraphPad Prism version 4.0 for Windows. AC, aged rat control group; CREB-1, cAMP responsive element binding protein 1; GINST, pectinase-treated Panax ginseng extract; GINST-AC, GINST-treated (200 mg/kg body weight) aged rat group; YC, young control rat group.

Fig. 8.

The effect of pectinase-treated Panax ginseng extract on the testicular mRNA expression level of nectin-2 involved in the sex hormone-related spermatogenesis pathway in young and aged rats. The protocol described in the Materials and methods section 2.4, 2.6 was followed. Total RNA was extracted from 50 mg testes tissue of young and aged rats and was reverse-transcribed for 50 min at 37°C. (A) An aliquot (200 ng) of the reverse-transcribed products was amplified and was separated with electrophoresis on a 2.0% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as an internal control. (B) The polymerase chain reaction band intensity of nectin-2 was analyzed using the ImageJ 1.41o software package and was normalized to that of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. The data are expressed at the mean ± standard deviation (n = 6). * p < 0.01 compared with the young control rat group. ** p < 0.05 compared with the aged rat control group as determined with Student t-test and one way analysis of variance using GraphPad Prism version 4.0 for Windows. AC, aged rat control group; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GINST, pectinase-treated Panax ginseng extract; GINST-AC, GINST-treated (200 mg/kg body weight) aged rat group; YC, young control rat group.

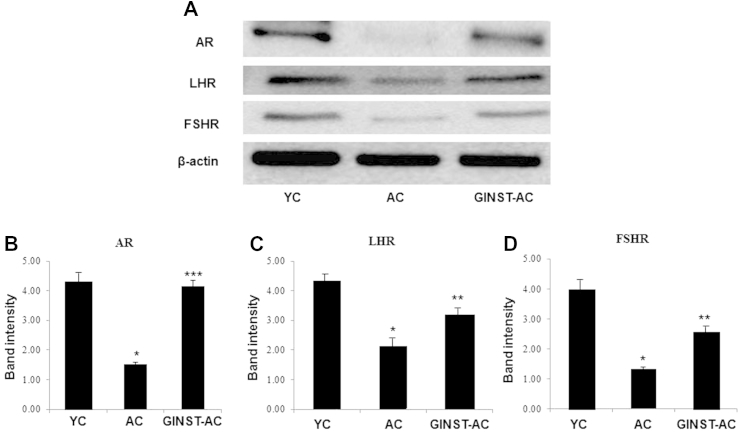

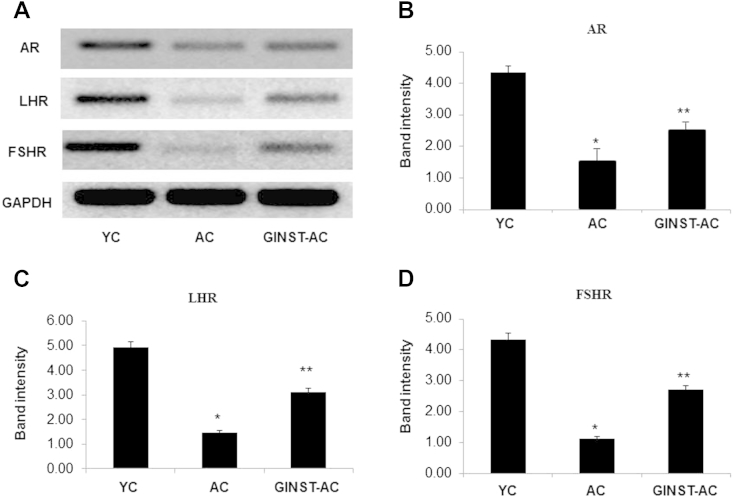

3.7. The effect of GINST on the protein and mRNA expression level of sex hormone receptors in the testes of aged rats

The testicular protein expression level of the AR, LHR, and FSHR was significantly (p < 0.01) decreased in the AC group compared with that in the YC group (Fig. 9A). AR and FSHR was more decreased than that of LHR (Figs. 9B–D). This decrease was significantly (p < 0.05) inhibited in the GINST-AC group. Similarly, the mRNA expression level of AR, LHR, and FSHR was decreased in the AC group compared with that in the YC group (Fig. 10A). LHR and FSHR being more decreased than that of AR (Figs. 10C, 10D). The mRNA expression decrease of all three receptors was significantly (p < 0.05) reversed in the GINST-AC group (Figs. 10B–10D).

Fig. 9.

The effect of pectinase-treated Panax ginseng extract on the testicular sex hormone receptor protein expression level in young and aged rats. The protocol described in the Materials and methods section 2.4, 2.5 was followed. The protein expression level of the androgen receptor (AR), follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR), and luteinizing hormone receptor (LHR) in rat testicular tissue was analyzed using western blotting. (A) Tissue lysates from the indicated groups were immunoblotted with specific antibodies against AR, FSHR, and LHR. Beta-actin was used as the internal control. (B–D) The protein band intensity of AR, LHR, and FSHR, respectively, normalized to that of β-actin is shown. The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 6). * p < 0.01 compared with the young control rat group. ** p < 0.05 compared with the aged rat control group. *** p < 0.01 compared with the aged rat control group as determined with Student t-test and one way analysis of variance using GraphPad Prism version 4.0 for Windows. AC, aged rat control group; AR, androgen receptor; FSHR, follicle-stimulating hormone receptor; GINST, pectinase-treated Panax ginseng extract; GINST-AC, GINST-treated (200 mg/kg body weight) aged rat group; LHR, luteinizing hormone receptor; YC, young control rat group.

Fig. 10.

The effect of pectinase-treated Panax ginseng extract on the testicular sex hormone receptor mRNA expression level in young and aged rats. The protocol described in the Materials and methods section 2.4, 2.6 was followed. Total RNA was extracted from 50 mg testes tissue of young and aged rats and was reverse-transcribed for 50 min at 37°C. (A) An aliquot (200 ng) of the reverse-transcribed products was amplified and was separated with electrophoresis on a 2.0% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as the internal control. (B–D) The polymerase chain reaction band intensity of androgen receptor, luteinizing hormone receptor, and follicle-stimulating hormone receptor, respectively, was analyzed using the ImageJ 1.41o software package and was normalized to that of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 6). * p < 0.01 compared with the young control rat group. ** p < 0.05 compared with the aged rat control group as determined with Student t-test and one way analysis of variance using GraphPad Prism version 4.0 for Windows. AC, aged rat control group; AR, androgen receptor; FSHR, follicle-stimulating hormone receptor; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GINST, pectinase-treated Panax ginseng extract; GINST-AC, GINST-treated (200 mg/kg body weight) aged rat group; LHR, luteinizing hormone receptor; YC, young control rat group.

4. Discussion

It is well known that oxidative stress resulting from excessive reactive oxygen species production has a negative impact on functional spermatogenic parameters and male fertility [26], [27], [28]. Several studies have shown that chemicals such as H2O2 (exogenously added or produced by sperm) are toxic to mammalian spermatozoon causing damage to the spermatic cell, including inhibition of motility and decline in energy metabolism [27], [29], [30].

However, it is also known that steroidogenesis decreases with aging and may be caused by an increase in testicular oxidative stress [31], [32]. Furthermore, experiments on Leydig cells from aged rats showed a reduced expression of key enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidants, which led to enhanced oxidative damage [33], [34]. Elements of the glutathione-dependent antioxidant system also decrease in aged rat testes [34], [35], which is consistent with what is known about increased oxidative stress and aging [36]. However, the intricate relationships between aging, oxidative stress, and testis function remain to be clarified. Therefore, in the present study, we examined the effect of H2O2-induced oxidative stress in mouse spermatocyte GC-2 cells. We also studied the effect of oxidative stress in aging by evaluating the changes in the molecular aspects due to aging-induced testicular inefficiency.

Our present study revealed that exposure to exogenous H2O2 adversely affected the viability of GC-2 cells. Our findings are in agreement with those reported in previously published studies showing that H2O2 exerts a direct cytotoxic effect against mouse spermatocyte GC-1 and GC-2 cells in vitro [37], [38] and sperm function in various species in vivo [29], [39], [40]. This study also confirmed the beneficial effects of GINST treatment (50 μg/mL and 100 μg/mL) on H2O2-induced oxidative stress. Previously, we reported that GINST had potent antioxidant effects and increased the protein expression level of enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidants in aged rats [3]. Therefore, GINST might improve the antioxidant status during H2O2-induced oxidative stress in GC-2 cells.

PRx proteins constitute a novel antioxidant protein family that plays a significant role in a number of vital biological processes in a variety of species [41], [42], [43]. Biochemical studies using cultured animal cells indicated that PRx proteins were among the main molecules that maintained the cellular redox potential [44]. The expression of PRx was significantly altered in response to treatment with ROS [45]. These results may imply that PRx is also involved in the H2O2-induced cytotoxicity in GC-2 cells and aging-induced testicular inefficiency caused by oxidative stress.

GST and GPx are expressed mainly in the cytoplasm and protect against lipid and nucleic acid peroxidation. GSTm5 was found to be enriched in the testes and in isolated spermatogenic cells [34], [46], [47]. GPx4 reduces complex lipid hydroperoxides, even if they are incorporated in bio-membranes or lipoproteins [48]. In addition to its anti-oxidative activity, GPx4 has been implicated as a structural protein in sperm maturation [49]. Therefore, we evaluated the effects of GINST on the expression of these genes in H2O2-induced GC-2 cells and also in vivo in aged and young rat testes. H2O2-treated GC-2 cells showed signs of oxidative damage as evidenced by a significant decrease in the mRNA expression level of PRx3 and 4, GSTm5, and GPx4, indicating that H2O2 indeed exerted oxidative stress in GC-2 cells. In agreement with these in vitro results, the protein and mRNA expression level of PRx3 and 4, GSTm5, and GPx4 also significantly (p < 0.01) decreased in aged rats compared with that in young rats. This decrease was ameliorated by GINST treatment, indicating that GINST might regulate the decreased antioxidant enzyme status in H2O2-induced GC-2 cells and aged rats, thereby exerting protective effects against aging-induced testicular inefficiency.

The spermatogenesis-related proteins nectin-2, CREB-1, and inhibin-α are major transcriptional factors involved in testicular function. Nectin-2 is an important adhesion molecule in the Sertoli germ cell junction, and aids in the development of the matured spermatozoa in the seminiferous epithelium [50]. The expression of the nectin-2 gene in the testes is crucial to the maintenance of normal spermatogenesis [51], [52]. Inhibin-α is responsible for the negative feedback mechanisms that suppress FSH production from the pituitary gland [53] and is important for the development of the round spermatid during the first wave of spermatogenesis [54]. CREB-1 is known to play several roles in the development and normal function of the testes. Previous studies have established the cAMP-dependent signal transduction pathway as a major regulatory mechanism during different stages of spermatogenesis [55]. CREB-1 is expressed during the mitotic phase of spermatocytogenesis and the differentiation phase of spermiogenesis, suggesting that it plays an important role in these processes [56]. Therefore, CREB-1 may be a key molecular regulator of testicular development and adult spermatogenesis in mice [55], [56]. In view of the published reports, in our study, H2O2 treatment decreased the mRNA expression level of inhibin-α in GC-2 cells. In aged rat testes, the protein and mRNA expression level of nectin-2 and the protein expression level of CREB-1 also decreased. These findings indicated that H2O2- and aging-induced oxidative stress might affect the functional and signal transduction pathway involved in spermatogenesis. GINST significantly reversed the oxidative stress- and aging-induced mRNA and protein expression alterations, suggesting that GINST might regulate certain key transcription factors and restore signal transduction.

Under normal physiological conditions, the sex hormone level in male testes is well-balanced [57], [58]. H2O2 is known to induce DNA damage and negatively affect the function and secretion of sex hormones in mouse testicular cells [34]. Previous reports have also indicated that the development and differentiation of sperm cells are maintained through the function of Sertoli cells and that they are mediated by the action of certain key hormones such as FSH [59]. Previously, we reported that GINST significantly restored the decreased serum sex hormone level, including that of testosterone, FSH, and LH [4]. In agreement with these previous findings, our present study showed a significant reduction in the sex hormone receptor level following treatment with H2O2. In addition, the expression level of the sex hormone receptors reduced in the aged rats compared with that in the young rats, and was attenuated by the GINST treatment. These results provide clear evidence that GINST may play a crucial role in regulating the serum sex hormone level and biomarker molecules responsible for sperm production and function.

In our previous report, we performed a 2-dimensional electrophoresis and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time-of-flight/time-of-flight mass spectrometry analysis and identified marked changes in the protein expression level in aged rat testes in response to GINST [4]. Proteomic analysis identified 14 proteins that were differentially expressed between the aged control and GINST-treated aged rat groups. The decreased expression level of GST and GPx was significantly up regulated in GINST-treated aged rats compared with that in the vehicle-treated aged rats. Furthermore, the lipid peroxidation level was higher in aged rats compared with that in young rats, but this change was reversed by the GINST treatment in the aged rat groups [4]. Further, high-performance liquid chromatography analysis of P. ginseng and GINST showed differences in their respective saponin contents. The detection peaks of the ginsenosides Rg1, Rg2 R, Rb1, Rb2, and Rd in the P. ginseng extract decreased after the enzyme treatment. However, the detection peak of CK in GINST was higher than that in the P. ginseng extract [4]. The results of our previous and the present study indicate that the enzymatic biotransformation of P. ginseng by pectinase enhanced testicular function via the alleviation of oxidative stress both in vitro and in vivo.

5. Conclusion

The present data suggests that GINST attenuates H2O2-induced oxidative stress in GC-2 cells and modulates the gene expression level of antioxidant enzymes and spermatogenic and sex hormone receptor-related proteins in aged rats. Therefore, GINST may be a potential natural agent that can protect against or treat oxidative stress-induced male subfertility and aging-induced male subfertility due to the lack of sperm number or activity.

Conflicts of interest

All contributing authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Korea Institute of Planning & Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, Forestry & Fisheries, Korea (Grant no: 113040-3).

References

- 1.Attele A.S., Wu J.A., Yuan C.S. Ginseng pharmacology: multiple constituents and multiple actions. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;58:1685–1693. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kopalli S.R., Hwang S.Y., Won Y.J., Kim S.W., Cha K.M., Han C.K., Hong J.Y., Kim S.K. Korean red ginseng extract rejuvenates testicular ineffectiveness and sperm maturation process in aged rats by regulating redox proteins and oxidative defense mechanisms. Exp Gerontol. 2015;69:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramesh T., Kim S.W., Sung J.H., Hwang S.Y., Sohn S.H., Yoo S.K., Kim S.K. Effect of fermented Panax ginseng extract (GINST) on oxidative stress and antioxidant activities in major organs of aged rats. Exp Gerontol. 2012;47:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Won Y.J., Kim B.K., Shin Y.K., Jung S.H., Yoo S.K., Hwang S.Y., Sung J.H., Kim S.K. Pectinase-treated Panax ginseng extract (GINST) rescues testicular dysfunction in aged rats via redox-modulating proteins. Exp Gerontol. 2014;53:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi H.K., Seong D.H., Rha K.H. Clinical efficacy of Korean red ginseng for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1995;7:181–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hwang S.Y., Sohn S.H., Wee J.J., Yang J.B., Kyung J.S., Kwak Y.S., Kim S.W., Kim S.K. Panax ginseng improves senile testicular function in rats. J Ginseng Res. 2010;34:327–335. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hwang S.Y., Kim W.J., Wee J.J., Choi J.S., Kim S.K. Panax ginseng improves survival and sperm quality in guinea pigs exposed to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo- p-dioxin. BJU Int. 2004;94:663–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim Y.S., Kim J.J., Cho K.H., Jung W.S., Moon S.K., Park E.K., Kim D.H. Biotransformation of ginsenoside Rb1, crocin, amygdalin, geniposide, puerarin, ginsenoside Re, hesperidin, poncirin, glycyrrhizin, and baicalin by human fecal microflora and its relation to cytotoxicity against tumor cells. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;18:1109–1114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bae E.A., Han M.J., Choo M.K., Park S.Y., Kim D.H. Metabolism of 20(S)- and 20(R)-ginsenoside Rg3 by human intestinal bacteria and its relation to in vitro biological activities. Biol Pharm Bull. 2002;25:58–63. doi: 10.1248/bpb.25.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karikura M., Miyase T., Tanizawa H., Taniyama T., Takino Y. Studies on absorption, distribution, excretion and metabolism of ginseng saponins. VII. Comparison of the decomposition modes of ginsenoside-Rb1 and -Rb2 in the digestive tract of rats. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1991;39:2357–2361. doi: 10.1248/cpb.39.2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akao T., Kanaoka M., Kobashi K. Appearance of compound K, a major metabolite of ginsenoside Rb1 by intestinal bacteria, in rat plasma after oral administration–measurement of compound K by enzyme immunoassay. Biol Pharm Bull. 1998;21:245–249. doi: 10.1248/bpb.21.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bae E.A., Kim N.Y., Han M.J., Choo M.K., Kim D.H. Transformation of ginsenoside to compound k (IH-901) by Lactic acid bacteria of human intestine. J Microbiol Biotech. 2003;13:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matao K. Metabolism of ginseng saponins, ginsenosides, by human intestinal flora. J Tradit Med. 1994;11:241–245. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasegawa H., Sung J.H., Huh J.H. Ginseng intestinal bacterial metabolite IH901 as a new anti-metastatic agent. Arch Pharm Res. 1997;20:539–544. doi: 10.1007/BF02975208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hasegawa H., Sung J.H., Benno Y. Role of human intestinal Prevotella oris in hydrolyzing ginseng saponins. Planta Med. 1997;63:436–440. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tawab M.A., Bahr U., Karas M., Wurglics M., Schubert-Zsilavecz M. Degradation of ginsenosides in humans after oral administration. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31:1065–1071. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.8.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bae E.A., Park S.Y., Kim D.H. Constitutive beta-glucosidases hydrolyzing ginsenoside Rb1 and Rb2 from human intestinal bacteria. Biol Pharm Bull. 2000;23:1481–1485. doi: 10.1248/bpb.23.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi Y.S., Han G.C., Han E.J., Park K.J., Sung J.H., Chung S.Y. Effects of compound K on insulin secretion and carbohydrate metabolism. J Ginseng Res. 2007;31:79–85. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wakabayashi C., Murakami K., Hasegawa H., Murata J., Saiki I. An intestinal bacterial metabolite of ginseng protopanaxadiol saponins has the ability to induce apoptosis in tumor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;246:725–730. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi H.S., Kim S.Y., Park Y., Jung E.Y., Suh H.J. Enzymatic transformation of ginsenosides in Korean Red Ginseng (Panax ginseng Meyer) extract prepared by Spezyme and Optidex. J Ginseng Res. 2014;38:264–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasegawa H., Uchiyama M. Antimetastatic efficacy of orally administered ginsenoside Rb1 in dependence on intestinal bacterial hydrolyzing potential and significance of treatment with an active bacterial metabolite. Planta Med. 1998;64:696–700. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen G.T., Yang M., Song Y., Lu Z.Q., Zhang J.Q., Huang H.L., Wu L.J., Guo D.A. Microbial transformation of ginsenoside Rb(1) by Acremonium strictum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;77:1345–1350. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1258-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu R.Q., Yuan J.L., Ma L.Y., Qin Q.X., Wu X.Y. Probiotics improve obesity-associated dyslipidemia and insulin resistance in high-fat diet-fed rats. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2013;15:1123–1127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuan H.D., Quan H.Y., Jung M.S., Kim S.J., Huang B., Kim do Y., Chung S.H. Anti-diabetic effect of pectinase-processed ginseng radix (GINST) in high fat fiet-fed ICR mice. J Ginseng Res. 2011;35:308–314. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2011.35.3.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huo R., He Y., Zhao C., Guo X.J., Lin M., Sha J.H. Identification of human spermatogenesis-related proteins by comparative proteomic analysis: a preliminary study. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:1109–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.07.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aitken R.J. The complexities of conception. Science. 1995;269:39–40. doi: 10.1126/science.7604276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Armstrong J.S., Rajasekaran M., Chamulitrat W., Gatti P., Hellstrom W.J., Sikka S.C. Characterization of reactive oxygen species induced effects on human spermatozoa movement and energy metabolism. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26:869–880. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00275-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peris S.I., Bilodeau J.F., Dufour M., Bailey J.L. Impact of cryopreservation and reactive oxygen species on DNA integrity, lipid peroxidation, and functional parameters in ram sperm. Mol Reprod Dev. 2007;74:878–892. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bilodeau J.F., Blanchette S., Cormier N., Sirard M.A. Reactive oxygen species-mediated loss of bovine sperm motility in egg yolk Tris extender: protection by pyruvate, metal chelators and bovine liver or oviductal fluid catalase. Theriogenology. 2002;57:1105–1122. doi: 10.1016/s0093-691x(01)00702-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garg A., Kumaresan A., Ansari M.R. Effects of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) on fresh and cryopreserved buffalo sperm functions during incubation at 37 degrees C in vitro. Reprod Domest Anim. 2009;44:907–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2008.01115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zirkin B.R., Chen H. Regulation of Leydig cell steroidogenic function during aging. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:977–981. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.4.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Syntin P., Robaire B. Sperm structural and motility changes during aging in the Brown Norway rat. J Androl. 2001;22:235–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cao L., Leers-Sucheta S., Azhar S. Aging alters the functional expression of enzymatic and non-enzymatic anti-oxidant defense systems in testicular rat Leydig cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;88:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo L., Chen H., Trush M.A., Show M.D., Anway M.D., Zirkin B.R. Aging and the brown Norway rat leydig cell antioxidant defense system. J Androl. 2006;27:240–247. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.05075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mueller A., Hermo L., Robaire B. The effects of aging on the expression of glutathione S-transferases in the testis and epididymis of the Brown Norway rat. J Androl. 1998;19:450–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sastre J., Pallardo F.V., Vina J. Mitochondrial oxidative stress plays a key role in aging and apoptosis. IUBMB Life. 2000;49:427–435. doi: 10.1080/152165400410281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park E.H., Chang M.S., Kil K.J., Park S.K. The antioxidant activity of nelumbinis stamen in GC-2 spd(ts) cells. Korea J Herbol. 2012;27:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oh M.S., Kim D.R., Kim S.Y., Chang M.S., Park S.K. Antioxidant effects of psoraleae fructus in GC-1 cells. Kor J Ori Med Physiol Pathol. 2005;19:81–86. [Google Scholar]

- 39.du Plessis S.S., McAllister D.A., Luu A., Savia J., Agarwal A., Lampiao F. Effects of H(2)O(2) exposure on human sperm motility parameters, reactive oxygen species levels and nitric oxide levels. Andrologia. 2010;42:206–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2009.00980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Flaherty C.M., Beorlegui N.B., Beconi M.T. Reactive oxygen species requirements for bovine sperm capacitation and acrosome reaction. Theriogenology. 1999;52:289–301. doi: 10.1016/S0093-691X(99)00129-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Com E., Evrard B., Roepstorff P., Aubry F., Pineau C. New insights into the rat spermatogonial proteome: identification of 156 additional proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2003;2:248–261. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300010-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iuchi Y., Okada F., Tsunoda S., Kibe N., Shirasawa N., Ikawa M., Okabe M., Ikeda Y., Fujii J. Peroxiredoxin 4 knockout results in elevated spermatogenic cell death via oxidative stress. Biochem J. 2009;419:149–158. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wonsey D.R., Zeller K.I., Dang C.V. The c-Myc target gene PRDX3 is required for mitochondrial homeostasis and neoplastic transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6649–6654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102523299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang P., Liu B., Kang S.W., Seo M.S., Rhee S.G., Obeid L.M. Thioredoxin peroxidase is a novel inhibitor of apoptosis with a mechanism distinct from that of Bcl-2. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30615–30618. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.30615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee C.K., Kim H.J., Lee Y.R., So H.H., Park H.J., Won K.J., Park T., Lee K.Y., Lee H.M., Kim B. Analysis of peroxiredoxin decreasing oxidative stress in hypertensive aortic smooth muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1774:848–855. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rao A.V., Shaha C. Role of glutathione S-transferases in oxidative stress-induced male germ cell apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;29:1015–1027. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fulcher K.D., Welch J.E., Klapper D.G., O'Brien D.A., Eddy E.M. Identification of a unique mu-class glutathione S-transferase in mouse spermatogenic cells. Mol Reprod Dev. 1995;42:415–424. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080420407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomas J.P., Geiger P.G., Maiorino M., Ursini F., Girotti A.W. Enzymatic reduction of phospholipid and cholesterol hydroperoxides in artificial bilayers and lipoproteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1045:252–260. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(90)90128-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ursini F., Heim S., Kiess M., Maiorino M., Roveri A., Wissing J., Flohe L. Dual function of the selenoprotein PHGPx during sperm maturation. Science. 1999;285:1393–1396. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5432.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morrison M.E., Racaniello V.R. Molecular cloning and expression of a murine homolog of the human poliovirus receptor gene. J Virol. 1992;66:2807–2813. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.2807-2813.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mueller S., Rosenquist T.A., Takai Y., Bronson R.A., Wimmer E. Loss of nectin-2 at Sertoli-spermatid junctions leads to male infertility and correlates with severe spermatozoan head and midpiece malformation, impaired binding to the zona pellucida, and oocyte penetration. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:1330–1340. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.014670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bouchard M.J., Dong Y., McDermott B.M., Jr., Lam D.H., Brown K.R., Shelanski M., Bellve A.R., Racaniello V.R. Defects in nuclear and cytoskeletal morphology and mitochondrial localization in spermatozoa of mice lacking nectin-2, a component of cell-cell adherens junctions. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2865–2873. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.8.2865-2873.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hsueh A.J., Dahl K.D., Vaughan J., Tucker E., Rivier J., Bardin C.W., Vale W. Heterodimers and homodimers of inhibin subunits have different paracrine action in the modulation of luteinizing hormone-stimulated androgen biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:5082–5086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.14.5082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cai K., Hua G., Ahmad S., Liang A., Han L., Wu C., Yang F., Yang L. Action mechanism of inhibin alpha-subunit on the development of Sertoli cells and first wave of spermatogenesis in mice. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25585. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Don J., Stelzer G. The expanding family of CREB/CREM transcription factors that are involved with spermatogenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;187:115–124. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00696-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim J.S., Song M.S., Seo H.S., Yang M., Kim S.H., Kim J.C., Kim H., Saito T.R., Shin T., Moon C. Immunohistochemical analysis of cAMP response element-binding protein in mouse testis during postnatal development and spermatogenesis. Histochem Cell Biol. 2009;131:501–507. doi: 10.1007/s00418-009-0554-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sodersten P., Gustafsson J.A. A way in which estradiol might play a role in the sexual behavior of male rats. Horm Behav. 1980;14:271–274. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(80)90035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Engelking L.R. NewMedia T; Wyoming, USA: 2000. Metabolic and endocrine physiology. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huleihel M., Lunenfeld E. Regulation of spermatogenesis by paracrine/autocrine testicular factors. Asian J Androl. 2004;6:259–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]