Abstract

A 60-year-old man presented with cutaneous vasculitis, leucopenia and psoriasis. He was treated initially with ciclosporin A. On withdrawal of ciclosporin, due to inadequate improvement of cutaneous vasculitis, he developed psoriatic arthritis. Worsening neutropenia and pancytopenia, believed to be immune mediated, developed. He was treated with prednisolone, methotrexate and adalimumab but developed pneumocystis pneumonia. Leucocyte levels improved markedly with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). However, whilst being treated with G-CSF his condition deteriorated. He developed gastrointestinal and neurological symptoms and progressive weight loss. Diagnosis was delayed, but eventually polyarteritis nodosa was diagnosed and he was treated with cyclophosphamide. The patient improved initially but died from small bowel perforation due to vasculitis. Evidence showing a temporal association of his deterioration with use of G-CSF is shown. The use of G-CSF in patients with autoimmune conditions including vasculitis should be undertaken with great caution.

INTRODUCTION

The estimated annual incidence of polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is one in a million. Disease presentation is varied and diagnosis commonly delayed. Leucopenia and thrombocytopenia occur rarely in PAN [1]. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) is commonly used to treat neutropenia especially if there is concern about infection. A patient with a rare combination of autoimmune diseases including psoriasis, cutaneous vasculitis, pancytopenia and psoriatic arthritis, who developed systemic PAN and deteriorated strikingly after receiving G-CSF, is described.

CASE REPORT

A 60-year-old man with hypertension and longstanding psoriasis gave a 1-month history of fatigue and a painful rash affecting his hands and feet. Hand function and walking were impaired due to painful skin lesions. He did not have an arthropathy. He had quit smoking 25 years earlier. Psoriasis plaques affected his scalp and elbows and guttate lesions his limbs and trunk. Cutaneous vasculitis affected the right hand and left foot. Blood data at key time points are shown in Table 1.

Table 1:

Selected laboratory data at key time points.

| Presentation (Weeks 0–12) | Prior to G-CSF initiation (Weeks 260–269) | After G-CSF initiation (Weeks 270–305) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hb (g/l) | 138–147 | 120–129 | 81–125 |

| MCV (FL) (80–99) | 97–10 | 108–116 | 86–111 |

| WBC (×109/l) | 2.3–3.3 | 1.4–3.2 | 1.1–11.2 |

| Neutrophils (×109/l) | 1.0–1.5 | 0.2–0.5 | 0.3–8.8 |

| Lymphocytes (×109/l) | 0.9–1.3 | 0.5–2.0 | 0.1–2.0 |

| Eosinophils (×109/l) | 0 | 0 | 0–0.1 |

| Platelets (×109/l) | 153–201 | 85–124 | 56–149 |

| Prothrombin time (INR 0.8–1.2) | 0.9 | – | 1.0–1.4 |

| CRP (mg/l) | 9–10 | <3 | 7–201 |

| Creatinine (μmol/l) | 84–96 | 67–84 | 48–116 |

| Serology for hepatitis A, B, C and HIV | Negative | – | Negative |

| EBV DNA (copies/ml) | – | – | <500 |

| Cerebrospinal fluid cells | No cells | ||

| Cerebrospinal fluid protein (0.15–0.45 g/l) | – | – | Protein 0.62 |

| Creatine kinase (24–195 U/l) | 69 | – | 30–39 |

| Ferritin (18–360 μg/l) | 343–437 | – | 1330–2339 |

| Vitamin B12 (200–900 ng/l) | 267 | 231 | 310 |

| Folate (4–18 μg/l) | 7.6 | 6.8 | 5.4 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (135–225 U/l) | Normal | Normal | 231–290 |

| Immunoglobulins | |||

| IgG (6.0–16.0 g/l) | 10.2–11.8 | 10.9 | |

| IgA (0.8–4.0 g/l) | 3.8–5.6 | 4.0 | |

| IgM (0.5–2.0 g/l) | 1.8–6.3 | 1.7 | |

| Anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, anti-extractable nuclear antigens, anti-CCP, cryoglobulins, anti-cardiolipin | Negative | Negative | ANA 1:100 |

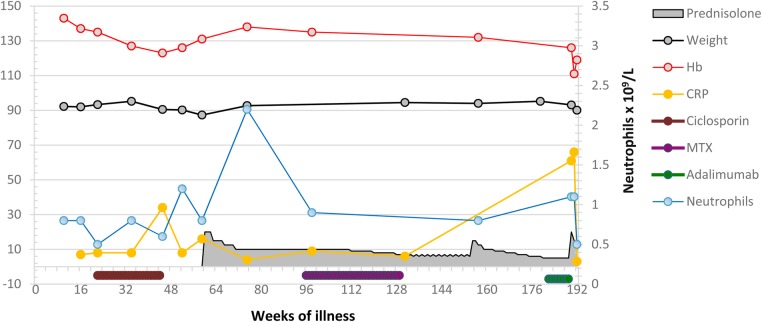

Ciclosporin (2 mg/kg) was started due to deteriorating skin psoriasis 20 weeks after presentation. The timeline of his illness is shown below, and reference to Figs 1 and 2 illustrates key events and laboratory data. His psoriasis improved, but skin vasculitis and neutropenia persisted. Ciclosporin was discontinued. His bone marrow showed granulocytic hyperplasia. It was concluded that neutropenia was immunologically mediated. A whole-body CT scan was normal.

Figure 1:

Laboratory data and key clinical parameters during the first phase of illness.

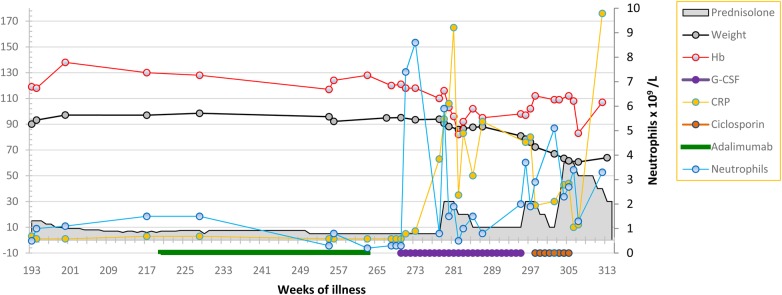

Figure 2:

Laboratory data and key clinical parameters during second phase of illness illustrating the impact of G-CSF.

He was treated with oral prednisolone. Skin vasculitis improved, but leucopenia persisted and the platelet count fell. On steroid taper, both psoriasis and vasculitis relapsed and he developed an inflammatory polyarthritis affecting hand joints and a knee (Week 99). He had ischemia of the tip of one his toes. This was attributed to small vessel vasculitis. The possibility of PAN was not considered. He started methotrexate (Week 101), but treatment was complicated by prolonged campylobacter gastroenteritis. Adalimumab, 40 mg subcutaneous every 2 weeks, was added (Week 183), but Pneumocystis jirovecci chest infection developed (Week 191, the CRP rose). Methotrexate and adalimumab were discontinued. Due to worsening skin psoriasis, adalimumab combined with co-trimoxazole prophylaxis was restarted (Week 220). He remained stable with low-grade skin vasculitis, psoriasis and mild psoriatic arthritis on prednisolone (5 mg daily), adalimumab and co-trimoxazole until Week 260 when worsening leucopenia and macrocytosis (MCV 116 fL) developed. Bone marrow showed hypercellularity, erythroid and megakaryocytic dysplasia, left-shifted myeloid and erythroid activity without excess blasts. Karyotyping was normal. No evidence for reactive hemophagocytic syndrome was found.

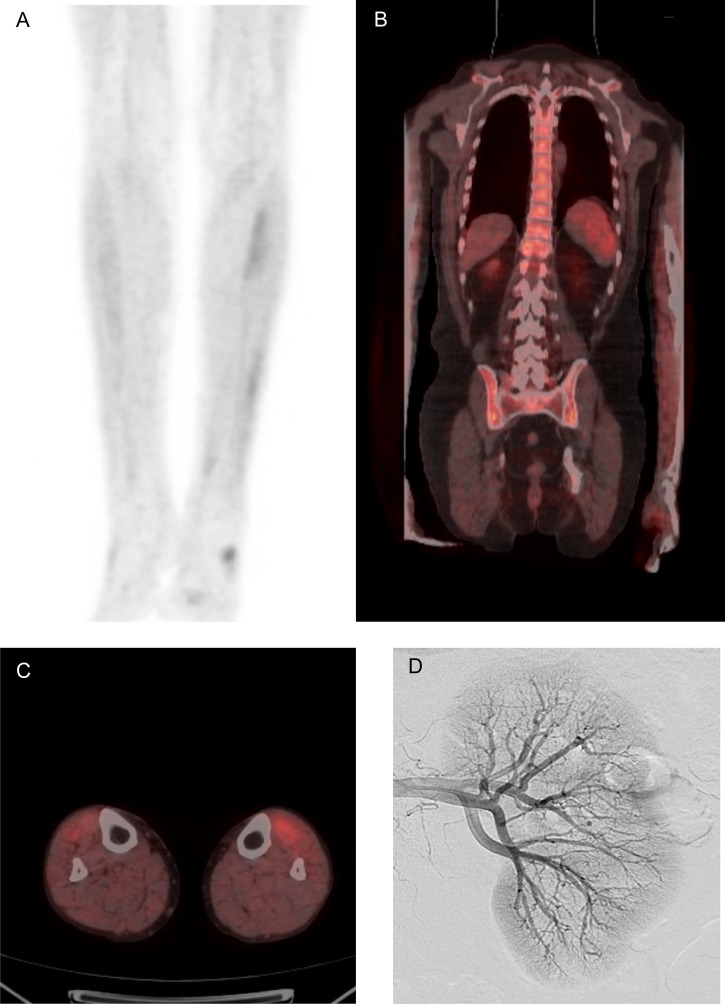

He was given G-CSF 300 μm thrice weekly with a good hematological response (Week 270, Fig. 2). Fever, night sweats, cough and dyspnea developed whilst on G-CSF and his CRP rose (Week 278). Intravenous antibiotics were administered, but an infectious cause was not identified. He improved briefly on increasing prednisolone but developed anorexia, weight loss (Fig. 2), abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. He described calf muscle pain on walking (Week 287). G-CSF was discontinued because of the possibility of drug toxicity (Week 295). In hospital, he developed ataxia, diplopia and Horner's syndrome. A brain and spine MRI and CSF examination were normal. A second fludeoxyglucose (18F) positron emission tomography CT (FDG-PET) scan showed diffuse increase in marrow activity and areas of muscular uptake (Fig. 3). A muscle biopsy was undertaken. Initial examination indicated a neuropathic process, but examination of formalin-fixed tissue showed segmental transmural inflammation with lymphocytes, occasional neutrophils and fibrinoid necrosis (Week 300).

Figure 3:

Radiological findings illustrating bone marrow uptake and organ involvement. [18F] Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan demonstrating increased uptake of FDG in the (A&C) calf musculature and (B) bone marrow of the axial skeleton, extending into the proximal humeri. (D) Digital subtraction imaging showing microaneurysms.

A colonoscopy was normal, but biopsies suggested acute on chronic ischemia. CT angiography showed patent mesenteric arteries and a low enhancing segment in the distal ileum. This finding was confirmed on MRI. Small bowel lymphoma was considered possible. Catheter angiography showed microaneurysms, arterial truncation and hypoperfusion throughout the superior mesenteric arterial branches, in the kidneys (Fig. 3) and liver.

Cyclophosphamide 750 mg (body weight of 61 kg, Week 305) was given intravenously at 2-week intervals. Appetite, energy, weight and walking improved, but days after a fourth infusion he died from acute bowel perforation (Week 314). Histology of resected small bowel showed focal perforation of the terminal ileum due to vasculitis.

DISCUSSION

Neutropenia and pancytopenia are exceptionally uncommon in PAN. Only one report, not associated with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis, was found in the literature [2]. Cutaneous vasculitis may occur in PAN. It is possible that his presenting illness was a limited form of PAN which later progressed. The development of profound neutropenia prompted the use of G-CSF in order to reduce infection risk. The neutrophil count rose but was followed by clinical decline (Fig. 2).

A diagnosis of PAN was delayed by several factors. First, an initially puzzling increase in bone marrow uptake was seen on FDG-PET. G-CSF is known to increase isotope uptake in bone marrow resulting in the appearance seen in Fig. 3 [3]. Second, CT angiography (CTA), advocated as first-line investigation in imaging bowel ischemia [4], showed a focal abnormality in the small bowel, possibly a lymphoma. This was not confirmed on conventional angiography, the gold standard test for assessing gut vasculature.

This patient's condition declined around 8 weeks after starting G-CSF. G-CSF stimulates neutrophil production from bone marrow and facilitates activation of neutrophils in an inflammatory environment by a variety of means [5]. Such activation could have led to a more intense inflammatory response, manifest by a rise in CRP following an increase in neutrophil levels. Whether his clinical deterioration can be attributed directly to G-CSF is uncertain. Determining a causal link between drug treatment and an adverse event in rare conditions is difficult. Indeed, certainty about an association between any adverse reaction and a drug is rare [6]. A temporal association is supportive but alone is insufficient to prove cause. However, supportive evidence comes from other reports, for example, of cutaneous vasculitis in 4% of patients with neutropenia treated with G-CSF and worsening of autoimmune diseases, including vasculitis, after G-CSF use [7, 8]. This case report indicates that progressive and fatal vasculitis, in the form of PAN, may develop from use of G-CSF in active autoimmune disease including vasculitis.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

This work was not funded.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

No ethical approval was required for this report.

CONSENT

Formal written consent was received from the patient's spouse and is available on request from the author.

GUARANTOR

P.J. is the guarantor for this work.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I am grateful to Drs Clare Oni and Gillian Lowe for their help with initial data review and extraction.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hernández-Rodríguez J, Alba MA, Prieto-González S, Cid MC. Diagnosis and classification of polyarteritis nodosa. J Autoimmunity 2014;48–9:84–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrold LR, Liu NYN. Polyarteritis nodosa presenting as pancytopenia: case report and review of the literature. Rheumatol Int 2008;28:1049–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacene HA, Ishimori T, Engles JM, Leboulleux S, Stearns V, Wahl RL. Effects of pegfilgrastim on normal biodistribution of 18-F-FDG: Preclinical and clinical studies. J Nucl Med 2006;47:950–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American College of Radiology. Appropriateness criteria: Imaging of mesenteric ischaemia. https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/70909/Narrative/ accessed January 23, 2016.

- 5.Bendall LJ, Bradstock KF. G-CSF: From granulopoietic stimulant to bone marrow stem cell mobilizing agent. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2014;25:355–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naidu RP. Causality assessment: a brief insight into practices in pharmaceutical industry. Perspect Clin Res 2013;4:233–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dale DC, Cottle TE, Fier CJ, Bolyard AA, Bonilla MA, Boxer LA et al. Severe chronic neutropenia: Treatment and follow-up of patients in the severe chronic neutropenia international registry. Am J Hematol 2003;72:82–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vial T, Descotes J. Immune-mediated side-effects of cytokines in humans. Toxicology 1995;105:31–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]