Abstract

We report a case of 63-year-old Chinese man, having a history of anti-myeloperoxidase (MPO) antibody anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated pulmonary-renal syndrome 9 years ago, presented with second episode of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN) and alveolar haemorrhage compatible with anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) disease. In first presentation, his anti-GBM antibody was negative. This time, anti-MPO antibody was negative, but anti-GBM antibody was positive. The long interval of sequential development of anti-GBM disease after ANCA-associated vasculitis in this patient may provide clues to the potential immunological links between these two distinct conditions. Clinicians should be aware of such double-positive association.

INTRODUCTION

Both myeloperoxidase (MPO)-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) and anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM)-associated pulmonary-renal syndromes are aggressive diseases carrying high mortality. Early recognition and prompt treatment are important. Co-existence of the two uncommon conditions in a single patient is more than chance occurrence. Clinicians should be aware of the potential immunological ‘cross-talk’ between them at the time of disease diagnosis, relapse or treatment refractoriness.

CASE REPORT

A 63-year-old Chinese man with a history of MPO-ANCA-associated systemic vasculitis 9 years ago, presented with pulmonary haemorrhage and rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN) that required temporary dialysis. Anti-MPO titre was >100 U/ml (<5 U/ml), and anti-GBM titre was normal (<7 U/l). He was treated with pulse steroid, plasmapheresis, intravenous cyclophosphamide and followed by azathioprine maintenance therapy. Anti-MPO level returned to normal (<5 U/ml) after 6 months. Immunosuppression was tapered off 8 years later as the disease was quiescent. Four months before admission, he had transient self-limiting rash over lower limbs, and prednisolone 5 mg daily was prescribed for minor cutaneous vasculitis. At that time, he had stable renal function, with Cr 180 μmol/l (65–110 μmol/l) and anti-MPO level <5 U/ml.

In the indexed admission, the patient presented with 1-week history of watery diarrhoea without fever, haemoptysis, rash or urinary symptom. He recalled a history of burning offerings to ancestral spirits in a kerosene tin 2 weeks before. Blood tests then showed markedly raised Cr 1053 μmol/l, low albumin 28 g/l (35–52 g/l), low haemoglobin 9.9 g/dl (13.4–17.1 g/dl) and elevated white cell count 13 × 109/l (3.7–9.2 × 109/l). He was initially managed as acute renal failure due to dehydration and gastroenteritis, started on fluid replacement, empirical antibiotics and stress dose of hydrocortisone. Renal ultrasonogram revealed parenchymal renal disease without obstructive uropathy.

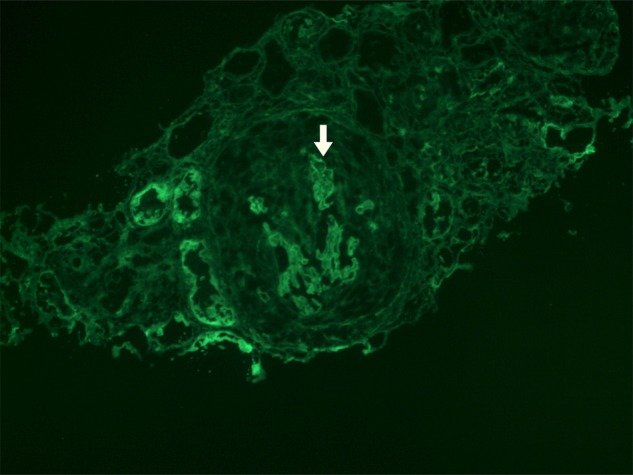

On the third day of admission, he complained of increasing breathing difficulty. Chest radiograph showed congested lung and bilateral pleural effusion. Sepsis workup was negative, and serum Cr was persistently raised 1077 μmol/l. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 95 mm/h (<17 mm/h) and C-reactive protein 156 mg/l (<5 mg/l). Echocardiogram showed mildly impaired ejection fraction (51%) and 6 mm pericardial effusion over right atrium and right ventricle. Immunology panel showed negative anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-extractable nuclear antibodies, normal anti-double-stranded DNA level and normal C3/C4 levels. Anti-proteinase-3 was <3 units (<20 units), and anti-MPO was <5 U/ml (<5 U/ml), but titre of anti-GBM was surprisingly high (122.2 U/l; normal <7 U/l). Renal biopsy revealed cellular crescent with compression of glomerular tuft and segmental fibrinoid necrosis, IgG (2+) and C3 (2+) linear staining along glomerular capillary wall consistent with anti-GBM disease (Fig. 1).

Figure 1:

Renal biopsy: immunofluorescence study showing IgG (2+) linear staining along GBM (arrowed) and crescent filling up Bowman's capsule.

The patient was put on alternate-day plasmapheresis, intravenous pulse methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide. Haemodialysis was started for acute renal failure and symptomatic fluid overload. Two weeks later, he developed acute respiratory failure and haemoptysis, requiring mechanical ventilation. Chest radiograph showed bilateral pulmonary infiltrates compatible with alveolar haemorrhage. His condition was further complicated with respiratory failure, shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation and acute myocardial injury. He succumbed on Day 26 of admission, despite board-spectrum antibiotics, daily plasmapheresis, nitric oxide therapy, N-acetylcysteine infusion and continuous veno-venous haemofiltration.

DISCUSSION

Anti-GBM disease, or Goodpasture's syndrome, is an autoantibody-mediated autoimmune small vessel vasculitis that classically presents as pulmonary-renal syndrome. It is a rare disease, having an annual incidence of 0.5–1 case per million, and presents with a bimodal age distribution. It contributes 10–20% of RPGN patients with crescents on renal biopsy. Both genetic and environmental factors like hydrocarbons exposure, tobacco, extracorporeal lithotripsy, virus and Clostridium botulinum have been implicated in the development of anti-GBM disease [1].

Advance in the understanding of molecular architecture of GBM autoantigen provides evidence that the co-occurrence of both MPO-ANCA and anti-GBM disease is far from coincidental. Development of autoimmunity of anti-GBM antibody involves a conformational epitope change on α3 and α5 non-collagenous proteins in the basement membrane of vascular epithelium of glomerular and alveolar tissues [2]. MPO-ANCA primed neutrophils, together with impaired clearance of reactive oxygen species and inactivation by ceruloplasmin, leaving a circulating reactive enzyme that produces MPO-derived oxidants. This alters the hexameric structure of GBM, therewith exposing, or ‘opens up’ the GBM epitope and initiates the development of antibody against non-collagenous domains of GBM. Anti-GBM circulates and deposits linearly to basement membrane, causing destruction of glomerular capillary walls, crescent formation and hence clinical disease. Experiment in rats demonstrated that autoantibodies to MPO could severely aggravate subclinical anti-GBM disease [3].

Co-existence of ANCA and anti-GBM diseases, or ‘double-positive’ diseases, is an uncommon but well-described clinical entity. Most of these cases had simultaneous detection of both ANCA and anti-GBM antibodies. A review of serology of ‘double-positive’ patients reported that 32% anti-GBM positive tests were also tested positive for ANCA, whereas 5% ANCA positive tests were tested positive for anti-GBM [4]. Furthermore, low level of ANCA might be detectable years before the detection of anti-GBM antibodies. In a recent study of 30 patients with anti-GBM disease, when compared with controls, almost all patients had detectable ANCA, either anti-PR3 or anti-MPO, before the onset of disease and even before anti-GBM antibody was detected [5]. Case reports with persistent positivity of ANCA and subsequent appearance of anti-GBM antibodies have been published [6–8]. Conversely, a case report demonstrating anti-GBM disease before the development of MPO-ANCA-associated vasculitis in a patient with genetic susceptibility to anti-GBM disease (HLA DR15) has been described, but the mechanism was unclear [9].

Our patient is unique because initially MPO-ANCA was positive for 1 year, and after intensive immunosuppression for pulmonary-renal syndrome, turned negative for 8 years, and by the ninth year while ANCA remained negative, anti-GBM antibodies emerged for the first time and coincided with another episode of life-threatening pulmonary-renal syndrome. This illustrates the potential pathogenic role of MPO-ANCA in the development of immunogenic anti-GBM antibody. In retrospect, the patient's anti-GBM disease might have been triggered by hydrocarbon exposure while burning offerings in kerosene tin before this admission—one of the steps in ‘multiple-hit’ mechanism. Clinicians should be aware of this double-positive relationship and consider monitoring anti-GBM antibody in patients with ANCA-related vasculitis especially in relapse and refractory disease.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Not applicable.

CONSENT

Not applicable. Patient deceased, and his relatives cannot be traced.

GUARANTOR

P.S.J.C. is the guarantor of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Silvarino R, Noboa O, Cervera R. Anti-glomerular basement membrane antibodies. Isr Med Assoc J 2014;16:727–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pedchenko V, Bondar O, Fogo AB, Vanacore R, Voziyan P, Kitching AR et al. Molecular architecture of the Goodpasture autoantigen in anti-GBM nephritis. N Engl J Med 2010;363:343–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heeringa P, Brouwer E, Klok PA, Huitema MG, van den Born J, Weening JJ et al. Autoantibodies to myeloperoxidase aggravate mild anti-glomerular-basement-membrane-mediated glomerular injury in the rat. Am J Pathol 1996;149:1695–706. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy JB, Hammad T, Coulthart A, Dougan T, Pusey CD. Clinical features and outcome of patients with both ANCA and anti-GBM antibodies. Kidney Int 2004;66:1535–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olson SW, Arbogast CB, Baker TP, Owshalimpur D, Oliver DK, Abbott KC et al. Asymptomatic autoantibodies associate with future anti-glomerular basement membrane disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;22:1946–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verburgh CA, Bruijn JA, Daha MR, van Es LA. Sequential development of anti-GBM nephritis and ANCA-associated Pauci-immune glomerulonephritis. Am J Kidney Dis 1999;34:344–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rutgers A, Slot M, van Paassen P, van Breda Vriesman P, Heeringa P, Tervaert JW. Coexistence of anti-glomerular basement membrane antibodies and myeloperoxidase-ANCAs in crescentic glomerulonephritis. Am J Kidney Dis 2005;46:253–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serratrice J, Chiche L, Dussol B, Granel B, Daniel L, Jego-Desplat S et al. Sequential development of perinuclear ANCA-associated vasculitis and anti-glomerular basement membrane glomerulonephritis. Am J Kidney Dis 2004;43:e26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peces R, Rodriguez M, Pobes A, Seco M. Sequential development of pulmonary hemorrhage with MPO-ANCA complicating anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody-mediated glomerulonephritis. Am J Kidney Dis 2000;35:954–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]