Abstract

Background

The Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC) has proposed a standardized definition of bleeding in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve interventions (TAVI). The VARC bleeding definition has not been validated or compared to other established bleeding definitions so far. Thus, we aimed to investigate the impact of bleeding and compare the predictivity of VARC bleeding events with established bleeding definitions.

Methods and Results

Between August 2007 and April 2012, 489 consecutive patients with severe aortic stenosis were included into the Bern‐TAVI‐Registry. Every bleeding complication was adjudicated according to the definitions of VARC, BARC, TIMI, and GUSTO. Periprocedural blood loss was added to the definition of VARC, providing a modified VARC definition. A total of 152 bleeding events were observed during the index hospitalization. Bleeding severity according to VARC was associated with a gradual increase in mortality, which was comparable to the BARC, TIMI, GUSTO, and the modified VARC classifications. The predictive precision of a multivariable model for mortality at 30 days was significantly improved by adding the most serious bleeding of VARC (area under the curve [AUC], 0.773; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.706 to 0.839), BARC (AUC, 0.776; 95% CI, 0.694 to 0.857), TIMI (AUC, 0.768; 95% CI, 0.692 to 0.844), and GUSTO (AUC, 0.791; 95% CI, 0.714 to 0.869), with the modified VARC definition resulting in the best predictivity (AUC, 0.814; 95% CI, 0.759 to 0.870).

Conclusions

The VARC bleeding definition offers a severity stratification that is associated with a gradual increase in mortality and prognostic information comparable to established bleeding definitions. Adding the information of periprocedural blood loss to VARC may increase the sensitivity and the predictive power of this classification.

Keywords: bleeding, complication, TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation, transcatheter aortic valve intervention, Valve Academic Research Consortium

Introduction

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has become an established treatment alternative to conventional, surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) in high‐risk patients with symptomatic, severe aortic stenosis and is considered the treatment of choice for inoperable patients.1, 2, 3, 4 Owing to the substantial differences in invasiveness between TAVI and SAVR, major bleeding complications and packed red blood cell (PRBC) transfusions have been shown to be 2 to 3 times less frequent among patients undergoing TAVI, compared to those undergoing SAVR, in the PARTNER trial.5 However, periprocedural bleeding complications post‐TAVI remain common, incur a significant increase in healthcare costs,6 and are associated with adverse clinical outcomes during long‐term follow‐up.5, 7, 8

Although early TAVI reports varied considerably in terms of frequency and type of complications owing to the lack of standardized endpoint definitions,9, 10, 11 this was successfully addressed by the Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC) in 2011.12 The first VARC consensus document aimed to harmonize endpoint definitions in TAVI trials and registries and provide guidance for uniform and standardized reporting of clinical outcomes. Subsequent to the implementation of these first set of guidelines, recommendations were revisited and updated in view of initial experiences and to address the future needs of clinical trials culminating in the VARC‐2 consensus document.13 Similar to the previous version, VARC‐2 categorizes bleeding complications according to the severity in minor, major, and in life‐threatening type and acknowledges the previously established recommendation of the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC).14 VARC‐2 endpoint definitions are based on expert consensus and have not been validated in a real‐world TAVI patient population to date. Thus, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the impact of bleeding according to the VARC‐2 endpoint definition on clinical outcomes and compare the predictive power of VARC‐2 bleeding events with other established bleeding definitions within the Bern TAVI cohort.

Methods

Patient Population

Between August 2007 and April 2012, 489 consecutive patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis were included into a single center registry (Bern TAVI Registry). All patients underwent TAVI with the self‐expanding Medtronic CoreValve (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN), the balloon‐expandable Edwards Sapien THV or XT prosthesis (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA) using the transfemoral, transapical, or subclavian access route, and the self‐expanding Symetis Acurate TA prosthesis (Symetis SA, Ecublens VD, Switzerland) using the transapical access route.11 Patients underwent TAVI after consensus reached within the local Heart Team consisting of invasive cardiologists and cardiac surgeon. With the institutional policy to perform TAVI using the least invasive strategy, device and access route selection was based on the individual anatomical characteristics after a sophisticated imaging evaluation using transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography, multislice computed tomography and coronary angiography. The study complied with the declaration of Helsinki, and the registry was approved by the local ethics committee. All patients provided written informed consent to participate in the registry with prospective follow‐up assessment.

Procedure

The procedure was performed according to local practice and expertise, as previously described.15 Periprocedural treatment consisted of unfractionated heparin (70 to 100 U/kg) to maintain an activated clotting time of more than 250 seconds, aspirin 100 mg qd, and clopidogrel (300 mg loading 1 day before the procedure followed by 75 mg qd for 3 to 6 months). For patients with an indication for oral anticoagulation, a vitamin K antagonist was combined with either low‐dose acetylsalicylic acid or clopidogrel and according to the individual bleeding risk. Heparin administration was not routinely reversed by using protamine sulfate at the end of a successful procedure. After the procedure, patients were either transferred to an intensive care unit or a coronary care unit and monitored for at least 48 hours after the intervention for rhythm disturbances, neurological deficits, access‐related and bleeding complications, or other serious adverse events. Blood sample and hemoglobin level assessment was performed at baseline, directly after the intervention, and was followed by a routine assessment on a daily basis among patients without signs of bleeding. Patients with bleeding complications had a hemoglobin assessment every 6 hours until stabilization as part of the routine institutional practice.

Data Collection and Endpoint Assessment

All patients were closely monitored during the index hospitalization and during follow‐up. After discharge, adverse events were assessed through active follow‐up at 30 days and 12 months by either clinical in‐hospital visits or a standardized telephone interview. In case of readmission to the hospital or other medical institutions, external medical records, discharge letters, and interventional reports including the full hematological report were systematically collected. Baseline clinical and procedural characteristics as well as follow‐up data were entered into a dedicated Web‐based database, held at an academic clinical trials unit (Clinical Trials Unit Bern, Bern University Hospital, Bern, Switzerland) responsible for central data audits and maintenance of the database.

All suspected events were presented to a dedicated clinical event committee consisting of cardiologists and cardiac surgeons, and serious adverse events were adjudicated according to the standardized endpoint definitions proposed by the Valve Academic Research Consortium.13

Definitions

For the purpose of this study, every single bleeding complication during the index hospitalization was reviewed by 2 investigators (S.S. and G.G.S.) according to the patient charts, available reports, and the full hematological report. After reevaluating the severity of the complications, all events were reclassified and adjudicated according to the bleeding definitions proposed by the Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC‐213), the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC14), the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction investigators (TIMI16), and the Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries investigators (GUSTO17). Both investigators (S.S. and G.G.S.) needed to agree on bleeding severity classification according to the predefined bleeding definitions, and in case of disagreement, adjudication was performed and disagreement resolved by a third investigator (S.W.).

For every single case of bleeding, the full source documentation was available and additional information for the localization of bleeding, several imaging tests, hemoglobin level, platelet count, and PRBC transfusion was collected. Furthermore, the hematological laboratory reports preceding TAVI and during the index hospitalization, as well as PRBC transfusions, were evaluated in all patients to identify peri‐ and postprocedural blood loss according to the definitions of VARC 2, BARC, TIMI, and GUSTO. Periprocedural blood loss was calculated from the baseline and the first blood sample assessment after the procedure, and the drop in hemoglobin was added to the definition criteria of VARC‐2 creating the modified VARC definition of bleeding.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed by a statistician at an academic clinical trials unit (D.H. and P.J., Clinical Trials Unit Bern, Bern University Hospital, Bern, Switzerland) using Stata software (version 12.1; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Categorical variables were summarized as counts and frequencies (%) and were compared by using the chi‐square test (or Fisher's test for 2 group comparisons), whereas continuous variables were presented as means±SD and compared using ANOVA. A description of the location and the severity of bleeding events adjudicated according to the updated VARC‐2 definition was presented as counts and frequencies (%). The first bleeding event during the index hospitalization after TAVI was described using the bleeding definition of VARC‐2, BARC, TIMI, and GUSTO. For every definition, mortality rates from patients with a bleeding event adjudicated according to the most severe bleeding category were compared with rates from patients that had less severe or no bleeding complication. Incidence rates as well as relative risks (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated using Poisson regression. Landmark analysis with a prespecified landmark at 30 days was performed to evaluate early and late RR of mortality associated with bleeding. Cox regression was used to evaluate the hazard ratio (HR) with 95% CI for death at 30 days, between 30 days and 1 year, and up to 1‐year follow‐up. Uni‐ and multivariate models were constructed to derive adjusted HRs with 95% CI for mortality at 30 days, including the baseline confounders age, sex, body mass index, previous stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and atrial fibrillation.

Sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy with respect to 30‐day mortality were calculated for the different bleeding definitions and compared with the McNemar tests, taking VARC2 life‐threatening bleeding complications as a reference. Likelihood ratio tests were performed for the different multivariate models, including bleeding events, and compared to a multivariate model with the baseline confounders age, sex, body mass index, previous stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and atrial fibrillation. The discriminatory power for mortality at 30 days of different multivariable models with and without bleeding complications according to the bleeding definitions of VARC‐2, BARC, TIMI, and GUSTO were assessed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Multivariable models were used to construct adjusted ROC curves and compute areas under the curve (AUCs). Bootstrap analysis (200 samples) was used to calculate CIs of AUC. A 2‐sided P value less than 0.05 was considered to indicated statistical significance.

Results

Between August 2007 and April 2012, 489 consecutive patients underwent TAVI using the femoral (79%), transapical (20%), and subclavian access route (1%) for treatment of symptomatic, severe aortic valve stenosis. Overall, a total of 130 patients (26.6%) had a bleeding complication during the index hospitalization. Scheduled follow‐up with prospective endpoint assessment was complete for all patients at 30 days and 12 months after TAVI (100%).

Baseline clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. At baseline, patients with in‐hospital bleeding complication were older (no bleeding vs in‐hospital bleeding 81.9±6.1 vs 83.9±4.5; P=0.001) and more frequently had previous bleeding events in their past medical history (10% vs 24%; P<0.001). Furthermore, they less frequently had previous coronary artery bypass grafting (18% vs 8%; P=0.007) and presented with smaller mean aortic valve area (0.61±0.21 vs 0.56±0.23; P=0.019), compared to patients without bleeding complication, during the index hospitalization. Procedural duration (no bleeding vs in‐hospital bleeding 64.9±31 vs 74.4±51 minutes; P=0.014) and overall in‐hospital length of stay (7.3±4 vs 8.8±7; P=0.004) were longer for patients with in‐hospital bleeding complication, whereas access route, valve type, and other procedural specifications and in‐hospital characteristics were similar between groups as displayed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics

| All Patients N=489 | no Bleedinga N=359 | Overt Bleeding N=130 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 82.5±5.7 | 81.9±6.1 | 83.9±4.5 | 0.001 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 269 (55) | 192 (53) | 77 (59) | 0.30 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.2±4.9 | 26.2±4.9 | 26.1±4.9 | 0.80 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 131 (27) | 95 (26) | 36 (28) | 0.82 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 304 (62) | 229 (64) | 75 (58) | 0.21 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 400 (82) | 295 (82) | 105 (81) | 0.79 |

| Past medical history | ||||

| Previous bleeding event, n (%) | 66 (13) | 35 (10) | 31 (24) | <0.001 |

| Previous myocardial infarction, n (%) | 77 (16) | 58 (16) | 19 (15) | 0.78 |

| Previous coronary artery bypass graft, n (%) | 77 (16) | 66 (18) | 11 (8) | 0.007 |

| Previous percutaneous coronary intervention, n (%) | 123 (25) | 94 (26) | 29 (22) | 0.41 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 106 (22) | 85 (24) | 21 (16) | 0.082 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 88 (18) | 66 (18) | 22 (17) | 0.79 |

| Clinical features | ||||

| Anemiab, n (%) | 276 (56) | 212 (59) | 64 (49) | 0.063 |

| Renal failure (GFR <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2) | 329 (67%) | 235 (65%) | 94 (72%) | 0.16 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 295 (60) | 219 (61) | 76 (58) | 0.68 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 139 (28) | 103 (29) | 36 (28) | 0.91 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 52.4±15.0 | 52.24±15.14 | 52.7±14.5 | 0.77 |

| Aortic valve area, cm2 | 0.60±0.2 | 0.61±0.2 | 0.56±0.2 | 0.019 |

| Mean transaortic gradient, mm Hg | 43.4±17.3 | 42.6±17.0 | 45.5±17.8 | 0.11 |

| Laboratory values | ||||

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 120.9±15.9 | 120.9±15.3 | 120.9±17.5 | 0.98 |

| Platelet count, ×109/L | 218.0±76.6 | 216.8±78.3 | 221.2±72.1 | 0.57 |

| Risk assessment | ||||

| Logistic EuroScore, % | 23.4±13.8 | 23.4±13.9 | 23.6±13.6 | 0.88 |

| EuroScore II, % | 8.5±8.1 | 8.6±8.7 | 8.2±6.5 | 0.62 |

| STS Score, % | 6.8±5.2 | 6.7±5.2 | 7.0±5.1 | 0.62 |

| Antithrombotic therapy | ||||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 303 (62) | 223 (63) | 80 (62) | 0.83 |

| Clopidogrel, n (%) | 98 (20) | 73 (21) | 25 (19) | 0.80 |

| Oral anticoagulation, n (%) | 131 (27) | 102 (29) | 29 (22) | 0.17 |

| Aspirin and clopidogrel, n (%) | 78 (16) | 60 (17) | 18 (14) | 0.49 |

| Oral anticoagulation and aspirin, n (%) | 26 (5) | 20 (6) | 6 (5) | 0.82 |

| Oral anticoagulation and clopidogrel, n (%) | 14 (3) | 10 (3) | 4 (3) | 1.00 |

| Oral anticoagulation, aspirin and clopidogrel, n (%) | 7 (1) | 6 (2) | 1 (1) | 0.68 |

Depicted are mean±SD with P values from ANOVAs, or counts (%) with P values from chi‐square tests. GFR indicates glomerular filtration rate; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

The “no bleeding” group includes 120 patients who have had periprocedural blood loss.

Anemia was defined as hemoglobin less than 120 g/L for women and less than 130 g/L for men.

Table 2.

Procedural Characteristics

| All Patients N=489 | No Bleedinga N=359 | Overt Bleeding N=130 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedural characteristics | ||||

| Procedure time, min | 67.4±37.4 | 64.9±30.9 | 74.4±51.1 | 0.014 |

| Length of hospital stay, days | 7.7±5.3 | 7.3±4.4 | 8.8±7.1 | 0.004 |

| General anesthesia, n (%) | 194 (40) | 143 (40) | 51 (39) | 0.92 |

| New onset of atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 36 (7) | 24 (7) | 12 (9) | 0.33 |

| Access route | 0.13 | |||

| Femoral, n (%) | 386 (79) | 276 (77) | 110 (85) | |

| Apical, n (%) | 97 (20) | 79 (22) | 18 (14) | |

| Subclavian, n (%) | 6 (1) | 4 (1) | 2 (2) | |

| Valve type | 0.51 | |||

| Medtronic CoreValve, n (%) | 267 (55) | 198 (55) | 69 (53) | |

| Edwards Sapien valve, n (%) | 219 (45) | 158 (44) | 61 (47) | |

| Symetis ACURATE TA, n (%) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Revascularization | ||||

| Concomitant PCI, n (%) | 80 (16) | 54 (15) | 26 (20) | 0.21 |

| Staged PCI, n (%) | 50 (10) | 33 (9) | 17 (13) | 0.24 |

| Procedural specifications | ||||

| Post‐TAVI—need for permanent pacemaker, n (%) | 122 (25) | 82 (23) | 40 (31) | 0.077 |

| Post‐TAVI—aortic regurgitation ≥2 | 56 (12%) | 41 (12%) | 15 (12%) | 1.00 |

| Valve in series, n (%) | 9 (2) | 7 (2) | 2 (2) | 1.00 |

| Antithrombotic therapy after TAVI (at discharge) | ||||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 399 (85) | 300 (86) | 99 (83) | 0.46 |

| Clopidogrel, n (%) | 363 (78) | 273 (78) | 90 (76) | 0.61 |

| Oral anticoagulation, n (%) | 145 (31) | 110 (32) | 35 (29) | 0.73 |

| Aspirin and clopidogrel, n (%) | 320 (68) | 241 (69) | 79 (66) | 0.65 |

| Oral anticoagulation and aspirin, n (%) | 87 (19) | 68 (19) | 19 (16) | 0.42 |

| Oral anticoagulation and clopidogrel, n (%) | 54 (12) | 42 (12) | 12 (10) | 0.62 |

| Oral anticoagulation, aspirin and clopidogrel, n (%) | 20 (4) | 16 (5) | 4 (3) | 0.79 |

Depicted are mean±SD or counts (%). PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

The “no bleeding” group includes 120 patients with periprocedural blood loss.

Bleeding Complications and Periprocedural Blood Loss

A total of 152 bleeding events were observed in 130 patients post‐TAVI during the index hospitalization. The majority of bleeding complications were considered access‐site related or have been classified as vascular events (66.4%) and were adjudicated as life‐threatening in 37.6%, major in 43.6%, and minor complication in 18.8% of events according to the VARC‐2 definition. A detailed list of the location and the severity assessment of bleeding events is provided in Table 3. Periprocedural blood loss without signs of overt bleeding was observed in 120 patients and has been classified as life‐threatening in 20.0%, major in 59.2%, and minor in 20.8% of events according to VARC2 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Location and Severity of All Bleeding Events According to VARC‐2

| Overt Bleeding Complications | In‐Hospital Bleeding Complications | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N=152 | Life‐Threatening N=65 | Major N=52 | Minor N=35 | PRBC Transfusion (Mean±SD) | |

| Access site, n (%) | 101 (66.4) | 38 (58.5) | 44 (84.6) | 19 (54.3) | 2.0±3.3 |

| Gastrointestinal, n (%) | 10 (6.6) | 5 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (14.3) | 1.8±1.8 |

| Pulmonary, n (%) | 4 (2.6) | 2 (3.1) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (2.9) | 2.0±1.0 |

| Intracranial, n (%) | 3 (2.0) | 3 (4.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.7±2.1 |

| Intraocular, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Retroperitoneal, n (%) | 5 (3.3) | 4 (6.2) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 4.4±2.1 |

| Genitourinary, n (%) | 6 (3.9) | 2 (3.1) | 2 (3.8) | 2 (5.7) | 1.3±2.0 |

| Pericardial, n (%) | 8 (5.3) | 8 (12.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5.0±4.5 |

| Other, n (%) | 12 (7.9) | 3 (4.6) | 3 (5.8) | 6 (17.1) | 2.1±3.0 |

| Epistaxis, n (%) | 3 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) | 2 (5.7) | 0±0.0 |

| Periprocedural blood loss, n (%) | 120 (44.1) | 24 (27.0) | 71 (57.7) | 25 (41.7) | 1.5±1.5 |

Depicted are counts (%). PRBC indicates packed red blood cell; VARC, Valve Academic Research Consortium.

Bleeding Complications and Mortality

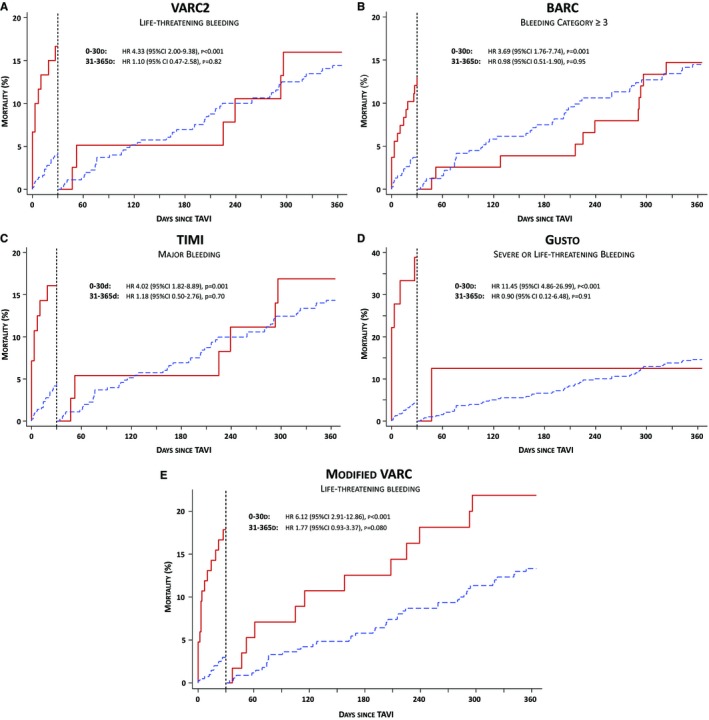

Among 489 patients undergoing TAVI, a total of 16 patients died during the index hospitalization before hospital discharge (3.3%), 28 deaths were observed within the first 30 days (5.7%), and 82 deaths within 12 months of follow‐up (16.8%). All‐cause death during the index hospitalization, at 30 days and 12 months mortality amounted to 0.4%, 2.1%, and 14.2% among patients with neither overt bleeding nor periprocedural blood loss, was 1.8%, 10.8%, and 23.4% among patients with bleeding complications, and amounted to 1.0%, 7.5%, and 25.2% among patients with periprocedural blood loss, respectively. A gradual increase in mortality was observed according to the severity of bleeding complication for VARC‐2, BARC, TIMI, GUSTO, and the modified VARC definition (Table 4). At 30 days, VARC‐2 life‐threatening, BARC ≥3, and TIMI major bleeding were associated with an approximately 4‐fold increased risk (HR, 4.3; 95% CI, 2.0 to 9.4; HR, 3.7; 95% CI, 1.8 to 7.7; HR, 4.0;, 95% CI, 1.8 to 8.9), compared to patients with no or less‐severe bleeding, whereas GUSTO severe or life‐threatening and the modified life‐threatening VARC classification were associated with a 12‐ and 6‐fold increased risk for mortality, respectively (HR, 11.5; 95% CI, 4.9 to 27.0; HR, 6.1; 95% CI, 2.9 to 12.9). Landmark analysis demonstrated an increased risk of mortality only during the first 30 days after the intervention for VARC‐2, BARC, TIMI, and GUSTO definitions, whereas the risk of mortality continued to increase up to 12 months of follow‐up with the modified VARC bleeding definition without reaching statistical significance (Table 5 and Figure 1).

Table 4.

In‐Hospital Bleeding and Mortality According to Various Bleeding Definitions

| Bleeding Definition Criteria Stratification | No. of Patients N=489 | Mortality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In‐Hospital N=16 | 30 Days N=28 | 1‐Year N=82 | ||

| No bleeding | 239 | 2 (0.8) | 5 (2.1) | 28 (14.2) |

| In‐hospital bleeding | 130 | 9 (6.9) | 14 (10.8) | 26 (23.4) |

| Periprocedural blood loss | 120 | 5 (4.2) | 9 (7.5) | 28 (25.2) |

| VARC‐2 | ||||

| VARC 2 (life‐threatening) | 60 | 8 (13.3) | 10 (16.7) | 16 (30.0) |

| VARC 2 (major) | 49 | 1 (2.0) | 4 (8.2) | 9 (20.2) |

| VARC 2 (minor) | 21 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) |

| BARC | ||||

| BARC 5b | 2 | 2 (100.0) | 2 (0.0) | 2 (0.0) |

| BARC 3c | 1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (27.0) | 1 (27.0) |

| BARC 3b | 57 | 6 (10.5) | 7 (12.3) | 13 (26.3) |

| BARC 3a | 48 | 1 (2.1) | 4 (8.3) | 9 (20.7) |

| BARC 2 | 22 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.1) |

| TIMI | ||||

| TIMI (major) | 56 | 8 (14.3) | 9 (16.1) | 15 (30.2) |

| TIMI (minor) | 51 | 1 (2.0) | 5 (9.8) | 10 (21.6) |

| TIMI (minimal) | 23 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.7) |

| GUSTO | ||||

| GUSTO (severe or life‐threatening) | 18 | 6 (33.3) | 7 (38.9) | 8 (46.5) |

| GUSTO (moderate) | 63 | 3 (4.8) | 5 (7.9) | 12 (22.1) |

| GUSTO (mild) | 49 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.2) | 6 (16.5) |

| Modified VARC | ||||

| Modified VARC (life‐threatening) | 84 | 13 (15.5) | 15 (17.9) | 27 (35.8) |

| Modified VARC (major) | 120 | 1 (0.8) | 7 (5.8) | 19 (17.5) |

| Modified VARC (minor) | 46 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) | 8 (23.5) |

Depicted are counts (cases over total for in‐hospital mortality and Kaplan–Meier incidence rates for 30 days and 1‐year mortality in %). BARC indicates Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; GUSTO, Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries investigators; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction investigators; VARC, Valve Academic Research Consortium.

Table 5.

In‐Hospital Bleeding: Bleeding Definition Criteria and Mortality

| Bleeding Definition Criteria | N | Mortality | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In‐Hospital | 30‐Day Follow‐up | 1‐Year Follow‐up | ||||||||

| Bleeding | Less Severe or No Bleeding | RR (95% CI) | Bleeding | Less Severe or No Bleeding | HR (95% CI) | Bleeding | Less Severe or No Bleeding | HR (95% CI) | ||

| VARC 2 LT | 60 (12.3) | 8 (13.3) | 8 (1.9) | 7.1 (2.8 to 18.4) | 10 (16.7) | 18 (4.2) | 4.3 (2.0 to 9.4) | 16 (26.7) | 66 (15.4) | 2.0 (1.2 to 3.5) |

| BARC ≥3 | 108 (22.1) | 9 (8.3) | 7 (1.8) | 4.5 (1.7 to 11.9) | 14 (13.0) | 14 (3.7) | 3.7 (1.8 to 7.7) | 25 (23.2) | 57 (15.0) | 1.7 (1.0 to 2.7) |

| BARC ≥2 | 130 (26.6) | 9 (6.9) | 7 (1.9) | 3.6 (1.3 to 9.3) | 14 (10.8) | 14 (3.9) | 2.9 (1.4 to 6.0) | 26 (20.0) | 57 (15.9) | 1.4 (0.9 to 2.3) |

| TIMI major | 56 (11.5) | 8 (14.3) | 8 (1.8) | 7.7 (3.0 to 19.8) | 9 (16.1) | 19 (4.4) | 4.0 (1.8 to 8.9) | 15 (26.8) | 67 (15.5) | 2.0 (1.2 to 3.6) |

| TIMI major+minor | 107 (21.9) | 9 (8.4) | 7 (1.8) | 4.6 (1.7 to 12.1) | 14 (13.1) | 14 (3.7) | 3.7 (1.8 to 7.8) | 25 (23.4) | 57 (14.9) | 1.7 (1.1 to 2.7) |

| GUSTO severe or LT | 18 (3.7) | 6 (33.3) | 10 (2.1) | 15.7 (6.4 to 38.5) | 7 (38.9) | 21 (4.5) | 11.5 (4.9 to 27.0) | 8 (44.4) | 74 (15.7) | 4.5 (2.2 to 9.4) |

| GUSTO severe or LT and moderate | 81 (16.6) | 9 (11.1) | 7 (1.7) | 6.5 (2.5 to 16.9) | 12 (14.8) | 16 (3.9) | 4.0 (1.9 to 8.5) | 20 (24.7) | 62 (15.2) | 1.8 (1.1 to 2.9) |

| Modified VARC LT | 84 (17.2) | 13 (15.5) | 3 (0.7) | 20.9 (6.1 to 71.8) | 15 (17.9) | 13 (3.2) | 6.1 (2.9 to 12.9) | 27 (32.1) | 55 (13.6) | 2.9 (1.8 to 4.6) |

This table considers only bleeding events occurring in the post‐procedural phase during index hospitalization. Only the first in‐hospital bleeding is considered in case of many in‐hospital bleeding event. For in‐hospital mortality, IRRs are computed using Poisson regression performed on 489 patients for each bleeding definition criteria. For 30‐day and 1‐year mortality, HRs are computed using Cox regression performed on 489 patients for each bleeding definition criteria. BARC indicates Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; CI, confidence interval; GUSTO, Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries investigators; HR, hazard ratio; IRR, incidence rate ratio; LT, life‐threatening; RR, relative risk; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction investigators; VARC, Valve Academic Research Consortium.

Figure 1.

Landmark analysis showing the risk of mortality at 30 days and from 30 days to 12 months of follow‐up in patients with symptomatic, severe aortic stenosis undergoing TAVI. Bleeding complications have been adjudicated according to the definition of VARC‐2, BARC, TIMI, GUSTO, and the modified VARC. Cumulative event curves are presented for patients with (red curve) and without bleeding event (blue curve) according to the definition of VARC‐2 (life‐threatening bleeding—A), of BARC (bleeding category ≥3—B), TIMI (major bleeding—C), GUSTO (severe or life‐threatening bleeding—D), and modified VARC (life‐threatening bleeding—E). BARC indicates Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; CI, confidence interval; GUSTO, Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries investigators; HR, hazard ratio; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction investigators; VARC, Valve Academic Research Consortium.

Predictors of Mortality and Predictive Power of Bleeding Definitions

The predictive precision of bleeding according to the definitions of VARC‐2, BARC, TIMI, GUSTO, and the modified VARC definition was assessed by calculating the c‐statistics for multivariable models by stepwise, including the bleeding events of each bleeding definition (Table 6). Bleeding, as well as periprocedural blood loss, was associated with a marked increase of mortality, which was independent of all baseline confounders.

Table 6.

Predictivity of the Multivariable Models Without and After Inclusion of Bleeding

| Multivariable Model | 30‐Day Mortality | |

|---|---|---|

| P Valuea | C‐Statistic [95% CI] | |

| Baseline model without bleedingb | — | 0.744 [0.671 to 0.818] |

| After inclusion of VARC‐2 LT bleeding | <0.001 | 0.773 [0.706 to 0.839] |

| After inclusion of bleeding defined as BARC ≥3 | 0.002 | 0.776 [0.694 to 0.857] |

| After inclusion of bleeding defined as BARC ≥2 | 0.011 | 0.762 [0.682 to 0.842] |

| After inclusion of TIMI major | 0.001 | 0.768 [0.692 to 0.844] |

| After inclusion of TIMI major+minor bleeding | 0.002 | 0.776 [0.701 to 0.852] |

| After inclusion of GUSTO severe or LT bleeding | <0.001 | 0.791 [0.714 to 0.869] |

| After inclusion of GUSTO severe or LT and moderate bleeding | 0.002 | 0.771 [0.692 to 0.851] |

| After inclusion of modified VARC LT bleeding | <0.001 | 0.814 [0.759 to 0.870] |

BARC indicates Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; GUSTO, Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries investigators; LT, life‐threatening; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction investigators; VARC, Valve Academic Research Consortium.

The P value is obtained from a likelihood ratio test comparing the baseline model without bleeding vs multivariable model including bleeding.

The baseline model includes age, sex, BMI, previous stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and atrial fibrillation at baseline.

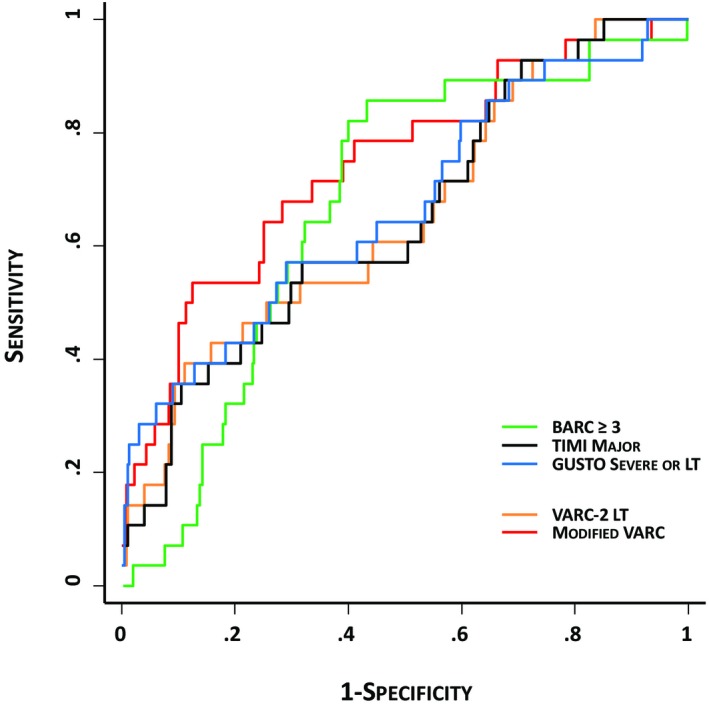

The predictive accuracy of VARC‐2, BARC, TIMI, GUSTO, and the modified VARC bleeding definition is presented in Table 7 and Figure 2. Whereas the sensitivity for 30 day mortality was similar between bleeding definitions, significant differences were observed for BARC, GUSTO, and the modified VARC definition, compared to the life‐threatening bleeding complication of VARC‐2. A nonsignificant increase in sensitivity and a significant decrease in specificity were observed by adding periprocedural blood loss to the VARC‐2 definition of life‐threatening bleeding without losing the accuracy of the definition.

Table 7.

Predictive Accuracy of Different Bleeding Definitions for 30‐Day Mortality

| VARC‐2 (LT) | BARC (Class ≥3) | BARC (Class ≥2) | TIMI (Major) | TIMI (Major+Minor) | GUSTO (Severe or LT) | GUSTO (Severe or LT and Moderate) | Modified VARC (LT) | BARC (Class ≥3) P Value | BARC (Class ≥2) P Value | TIMI (Major) P Value | TIMI (Major+Minor) P Value | GUSTO (Severe or LT) P Value | GUSTO (Severe or LT and Moderate) P Value | Modified VARC (LT) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 36% | 50% | 50% | 32% | 50% | 25% | 43% | 54% | 0.13 | 0.13 | 1.00 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.063 |

| Specificity | 89% | 80% | 75% | 90% | 80% | 98% | 85% | 85% | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.25 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Accuracy | 86% | 78% | 73% | 87% | 78% | 93% | 83% | 83% | 0.49 | 1.00 | 0.42 | 0.47 | 0.71 | 0.55 | 0.064 |

Data are percentages. Reference group for comparison of sensitivity, specificity: VARC2 LT. P value for Ho: equality of sensitivity/specificity. BARC indicates Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; GUSTO, Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries investigators; LT, life‐threatening; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction investigators; VARC, Valve Academic Research Consortium.

Figure 2.

Adjusted receiver operating characteristic curves showing the predictive ability of bleeding according to VARC, BARC, TIMI, GUSTO, and the modified VARC bleeding definition criteria for mortality at 30‐day follow‐up. BARC indicates Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; GUSTO, Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries investigators; LT, life‐threatening; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction investigators; VARC, Valve Academic Research Consortium.

Discussion

The present study investigating the predictive power of in‐hospital bleeding complications according to the updated VARC‐2 endpoint definitions on clinical outcomes has the following main findings:

Bleeding, according to the endpoint definition of VARC‐2, is independently associated with an increased risk of mortality at 30 days and 12 months of follow‐up post‐TAVI. Moreover, there is a gradual increase in impaired clinical outcome post‐TAVI with increasing severity of bleeding as defined by VARC‐2.

The predictive power of the VARC‐2 bleeding definition is comparable to previously established and validated bleeding definitions (BARC, TIMI, and GUSTO).

Periprocedural blood loss and a relevant drop of hemoglobin during TAVI is independently associated with an increased risk of mortality after 30 days and 12 months.

Adding the amount of periprocedural blood loss to the endpoint definition of VARC‐2 increases the predictive precision for impaired clinical outcomes.

During the initial TAVI experience, event reporting was inconsistent and complication rates were not comparable between trials and large, real‐world patients registries owing to the lack of standardized endpoint definitions. In 2011, VARC addressed this unmet scientific need and provided a consensus document with expert recommendations for a unified endpoint assessment after TAVI.12 VARC endpoint definitions have been rapidly adopted in the scientific community and currently serve as a reproducible and standardized tool to compare hemodynamic and clinical results post‐TAVI in routine clinical practice.

Bleeding complications are among the most frequent adverse events post‐TAVI and are observed in every fourth patient with relevant differences in severity. Two thirds of bleeding events are attributed to the access site and are considered vascular‐ or access‐related complications, which are independently associated with impaired clinical outcomes and responsible for a substantial increase in healthcare costs.6 At this point in time, current efforts in device iterations are mainly focused on the reduction of device‐related and, specifically, access‐related vascular complications with the development of novel TAVI delivery catheters and prostheses with a smaller and less‐traumatic profile and surface.

Recently, Généreux and coworkers draw attention to late bleeding events after hospital discharge.18 With an analysis on the incidence, predictors, and the prognostic impact of late bleeding complications post‐TAVI in the PARTNER patient population, these investigators observed a strong and independent association of late bleeding and mortality after 12 months of follow‐up (HRadj, 3.91; 95% CI, 2.67 to 5.71; P<0.001). Owing to the age and risk of the patient population included into the PARTNER trial, it was not surprising that gastrointestinal (40.8%) and neurological (15.5%) complications were among the most frequent late bleeding complications beyond 30 days of follow‐up. Given that these bleeding events have been mainly attributed to the patients’ bleeding susceptibility, the postoperative antiplatelet and ‐thrombotic management played a substantial role in this frail and vulnerable patient population. The results of currently ongoing studies (NCT01559298; NCT02247128; and NCT02224066) will soon inform the discussion on optimal medical therapy and the best antiplatelet strategy after a successful TAVI procedure.

Bleeding complications post‐TAVI are independently associated with worse clinical outcomes as reflected by a substantial increase in mortality at 30 days and 12 months after the intervention, a finding that is consistent with the results of previous studies investigating the impact of bleeding complications in a TAVI patient population.5, 7, 19, 20 It remains noteworthy that the deleterious effect of in‐hospital bleeding is only present within the first 30 days with no additional hazard arising between 30 days and 12 months after TAVI, as shown in our landmark analysis (Figure 1). This observation among TAVI patients differs from that in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), where a continuous and progressive risk of mortality is still apparent between 30 days and 12 months after the intervention.21 The reasons for this observation have not been evaluated so far, and an explanation might only be found in the inherent risk of the available confounders of a typical elderly TAVI patient population diluting the deleterious effect of periprocedural, in‐hospital bleeding after 30 days of follow‐up.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to validate bleeding as part of the updated VARC‐2 definitions in a large, consecutive patient population undergoing TAVI and comparing the predictive power of the VARC‐2 definition to already validated and accepted bleeding definitions of BARC, TIMI, and GUSTO in other settings. In this TAVI patient population, we found a strong association and a gradually increased risk between the severity of VARC‐2 bleeding events and mortality. The bleeding criteria and the severity stratified into VARC‐2 minor, major, and life‐threatening bleeding complications has been proven sensitive enough to identify and capture clinically relevant bleeding events and show a progressive increase in mortality at short‐ and long‐term follow‐up. Furthermore, the prognostic information and the performance of the updated VARC‐2 bleeding definition in a TAVI patient population were comparable to the established bleeding definitions of BARC, TIMI, and GUSTO with similar rates of sensitivity and accuracy.

Alongside with the existing predictive power of the VARC‐2 bleeding definitions for mortality, we were able to increase the sensitivity of the preexisting definition while maintaining the high rates of specificity and accuracy by creating a modified version of the VARC endpoint definitions. Whereas VARC‐2 explicitly mentions to capture only events of overt bleeding, we additionally estimated the periprocedural blood loss owing to procedural manipulation according to the preexisting definition, and by adding these events we provided a modified VARC definition. Life‐threatening bleeding according to the modified VARC definition was associated with a relevant 6‐fold increased risk of mortality at 30 days (HR, 6.1; 95% CI, 2.9 to 12.9) and an almost 3‐fold increased risk at 12 months of follow‐up (HR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.8 to 4.6). Of note, we found a continuous and progressive risk of mortality with a statistical trend between 30 days and 12 months (HR, 1.77; 95% CI, 0.93 to 3.37; Figure 1), which is similar to what has been observed in PCI populations.

Limitations

Several limitations need to be acknowledged, when interpreting the results of this study. First, the study population is based on the experience of a single, tertiary care center, and the results may not be applicable to other centers with different procedural experience as well as device and patient selection. Second, owing to the sample size of the present study and the respective event rates among patients with bleeding complications at 30‐day follow‐up, this could have particular impact on the results when comparing the different classifications of bleeding. Third, although details on bleeding complications have been prospectively collected, we are not able to exclude some heterogeneity and bias during the adjudication process according to the endpoint definitions of VARC, BARC, TIMI, and GUSTO. And, finally, although blood sample assessment was standardized for all patients on the morning of the intervention and daily thereafter until hospital discharge, a certain dilutional effect of periprocedural fluid management might be depicted in the analysis on periprocedural blood loss.

Conclusion

Bleeding complications post‐TAVI are frequent and independently associated with impaired clinical outcomes at short‐ and long‐term follow‐up. The current VARC‐2 bleeding definition offers a balanced severity stratification that is associated with a gradual increase in mortality and prognostic information that is comparable to established bleeding definitions (BARC, TIMI, and GUSTO). Adding the information of periprocedural blood loss to the preexisting definition of VARC‐2 may further increase the sensitivity and predictive power of this classification.

Disclosures

Prof Wenaweser has received honoraria and lecture fees from Medtronic and Edwards Lifesciences and has received an unrestricted grant from Medtronic to the institution (University of Bern). Prof Khattab has received speaker honoraria and proctor fees from Medtronic CoreValve and Edwards Lifesciences. Prof Jüni is an unpaid steering committee or statistical executive committee member of trials funded by Abbott Vascular, Biosensors, Medtronic, and Johnson & Johnson. CTU Bern, which is part of the University of Bern, has a staff policy of not accepting honoraria or consultancy fees. However, CTU Bern is involved in design, conduct, or analysis of clinical studies funded by Abbott Vascular, Ablynx, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Biosensors, Biotronic, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Exelixis, Geron, Gilead Sciences, Nestlé, Novartis, Novo Nordisc, Padma, Roche, Schering‐Plough, St Jude Medical, and Swiss Cardio Technologies. Prof Windecker reports having received research grants to the institution from Abbott, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Medicines Company, and St Jude as well as speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Abbott, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Bayer, and Biosensors. C. Huber is a proctor for Symetis and Edwards Lifesciences, serves as consultant for Medtronic, and has shares in Endoheart. All other authors have no relationships relevant to the contents of this article to disclose.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e002135 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002135)

References

- 1. Adams DH, Popma JJ, Reardon MJ, Yakubov SJ, Coselli JS, Deeb GM, Gleason TG, Buchbinder M, Hermiller J Jr, Kleiman NS, Chetcuti S, Heiser J, Merhi W, Zorn G, Tadros P, Robinson N, Petrossian G, Hughes GC, Harrison JK, Conte J, Maini B, Mumtaz M, Chenoweth S, Oh JK. Transcatheter aortic‐valve replacement with a self‐expanding prosthesis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1790–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, Miller DC, Moses JW, Svensson LG, Tuzcu EM, Webb JG, Fontana GP, Makkar RR, Brown DL, Block PC, Guyton RA, Pichard AD, Bavaria JE, Herrmann HC, Douglas PS, Petersen JL, Akin JJ, Anderson WN, Wang D, Pocock S. Transcatheter aortic‐valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1597–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Popma JJ, Adams DH, Reardon MJ, Yakubov SJ, Kleiman NS, Heimansohn D, Hermiller J Jr, Hughes GC, Harrison JK, Coselli J, Diez J, Kafi A, Schreiber T, Gleason TG, Conte J, Buchbinder M, Deeb GM, Carabello B, Serruys PW, Chenoweth S, Oh JK. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement using a self‐expanding bioprosthesis in patients with severe aortic stenosis at extreme risk for surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1972–1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, Miller DC, Moses JW, Svensson LG, Tuzcu EM, Webb JG, Fontana GP, Makkar RR, Williams M, Dewey T, Kapadia S, Babaliaros V, Thourani VH, Corso P, Pichard AD, Bavaria JE, Herrmann HC, Akin JJ, Anderson WN, Wang D, Pocock SJ. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic‐valve replacement in high‐risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2187–2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Genereux P, Cohen DJ, Williams MR, Mack M, Kodali SK, Svensson LG, Kirtane AJ, Xu K, McAndrew TC, Makkar R, Smith CR, Leon MB. Bleeding complications after surgical aortic valve replacement compared with transcatheter aortic valve replacement: insights from the PARTNER I Trial (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valve). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1100–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arnold SV, Lei Y, Reynolds MR, Magnuson EA, Suri RM, Tuzcu EM, Petersen JL II, Douglas PS, Svensson LG, Gada H, Thourani VH, Kodali SK, Mack MJ, Leon MB, Cohen DJ. Costs of periprocedural complications in patients treated with transcatheter aortic valve replacement: results from the placement of aortic transcatheter valve trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:829–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Borz B, Durand E, Godin M, Tron C, Canville A, Litzler PY, Bessou JP, Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H. Incidence, predictors and impact of bleeding after transcatheter aortic valve implantation using the balloon‐expandable Edwards prosthesis. Heart. 2013;99:860–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tchetche D, Van der Boon RM, Dumonteil N, Chieffo A, Van Mieghem NM, Farah B, Buchanan GL, Saady R, Marcheix B, Serruys PW, Colombo A, Carrie D, De Jaegere PP, Fajadet J. Adverse impact of bleeding and transfusion on the outcome post‐transcatheter aortic valve implantation: insights from the Pooled‐RotterdAm‐Milano‐Toulouse In Collaboration Plus (PRAGMATIC Plus) initiative. Am Heart J. 2012;164:402–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thomas M, Schymik G, Walther T, Himbert D, Lefevre T, Treede H, Eggebrecht H, Rubino P, Michev I, Lange R, Anderson WN, Wendler O. Thirty‐day results of the SAPIEN aortic Bioprosthesis European Outcome (SOURCE) Registry: a European registry of transcatheter aortic valve implantation using the Edwards SAPIEN valve. Circulation. 2010;122:62–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Piazza N, van Gameren M, Juni P, Wenaweser P, Carrel T, Onuma Y, Gahl B, Hellige G, Otten A, Kappetein AP, Takkenberg JJ, van Domburg R, de Jaegere P, Serruys PW, Windecker S. A comparison of patient characteristics and 30‐day mortality outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve implantation and surgical aortic valve replacement for the treatment of aortic stenosis: a two‐centre study. EuroIntervention. 2009;5:580–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wenaweser P, Pilgrim T, Roth N, Kadner A, Stortecky S, Kalesan B, Meuli F, Bullesfeld L, Khattab AA, Huber C, Eberle B, Erdos G, Meier B, Juni P, Carrel T, Windecker S. Clinical outcome and predictors for adverse events after transcatheter aortic valve implantation with the use of different devices and access routes. Am Heart J. 2011;161:1114–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leon MB, Piazza N, Nikolsky E, Blackstone EH, Cutlip DE, Kappetein AP, Krucoff MW, Mack M, Mehran R, Miller C, Morel MA, Petersen J, Popma JJ, Takkenberg JJ, Vahanian A, van Es GA, Vranckx P, Webb JG, Windecker S, Serruys PW. Standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation clinical trials: a consensus report from the Valve Academic Research Consortium. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:253–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kappetein AP, Head SJ, Genereux P, Piazza N, van Mieghem NM, Blackstone EH, Brott TG, Cohen DJ, Cutlip DE, van Es GA, Hahn RT, Kirtane AJ, Krucoff MW, Kodali S, Mack MJ, Mehran R, Rodes‐Cabau J, Vranckx P, Webb JG, Windecker S, Serruys PW, Leon MB. Updated standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the Valve Academic Research Consortium‐2 consensus document. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1438–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, Gibson CM, Caixeta A, Eikelboom J, Kaul S, Wiviott SD, Menon V, Nikolsky E, Serebruany V, Valgimigli M, Vranckx P, Taggart D, Sabik JF, Cutlip DE, Krucoff MW, Ohman EM, Steg PG, White H. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123:2736–2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wenaweser P, Pilgrim T, Kadner A, Huber C, Stortecky S, Buellesfeld L, Khattab AA, Meuli F, Roth N, Eberle B, Erdos G, Brinks H, Kalesan B, Meier B, Juni P, Carrel T, Windecker S. Clinical outcomes of patients with severe aortic stenosis at increased surgical risk according to treatment modality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2151–2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rao AK, Pratt C, Berke A, Jaffe A, Ockene I, Schreiber TL, Bell WR, Knatterud G, Robertson TL, Terrin ML. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Trial–phase I: hemorrhagic manifestations and changes in plasma fibrinogen and the fibrinolytic system in patients treated with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator and streptokinase. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;11:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. An international randomized trial comparing four thrombolytic strategies for acute myocardial infarction. The GUSTO investigators. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:673–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Genereux P, Cohen DJ, Mack M, Rodes‐Cabau J, Yadav M, Xu K, Parvataneni R, Hahn R, Kodali SK, Webb JG, Leon MB. Incidence, predictors, and prognostic impact of late bleeding complications after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:2605–2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Konigstein M, Ben‐Assa E, Banai S, Shacham Y, Ziv‐Baran T, Abramowitz Y, Steinvil A, Leshem Rubinow E, Havakuk O, Halkin A, Keren G, Finkelstein A, Arbel Y. Periprocedural bleeding, acute kidney injury, and long‐term mortality after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31:56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pilgrim T, Stortecky S, Luterbacher F, Windecker S, Wenaweser P. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation and bleeding: incidence, predictors and prognosis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2013;35:456–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ndrepepa G, Schuster T, Hadamitzky M, Byrne RA, Mehilli J, Neumann FJ, Richardt G, Schulz S, Laugwitz KL, Massberg S, Schomig A, Kastrati A. Validation of the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium definition of bleeding in patients with coronary artery disease undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2012;125:1424–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]