Abstract

Background

Although animal studies have documented metformin's cardioprotective effects, the impact in humans remains elusive. The study objective was to explore the association between metformin and myocardial infarct size in patients with diabetes presenting with ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Methods and Results

Data extraction used the National Cardiovascular Data CathPCI Registry in all patients with diabetes aged >18 years presenting with ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction at 2 academic medical centers from January 2010 to December 2013. The exposure of interest was ongoing metformin use before the event. Propensity score matching was used for the metformin and nonmetformin groups on key prognostic variables. All matched pairs had acceptable D scores of <10%, confirming an efficient matching procedure. The primary outcome was myocardial infarct size, reflected by peak serum creatine kinase–myocardial band, troponin T, and hospital discharge left ventricular ejection fraction. Of all 1726 ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction cases reviewed, 493 patients had diabetes (28.5%), with 208 metformin users (42.1%) and 285 nonusers. Matched pairs analysis yielded 137 cases per group. The difference between metformin and nonmetformin groups was −18.1 ng/mL (95% CI −55.0 to 18.8; P=0.56) for total peak serum creatine kinase–myocardial band and −1.1 ng/mL (95% CI −2.8 to 0.5; P=0.41) for troponin T. Median discharge left ventricular ejection fraction in both groups was 45, and the difference between metformin and nonmetformin users was 0.7% (95% CI −2.2 to 3.6; P=0.99).

Conclusions

No statistically significant association of cardioprotection was found between metformin and myocardial infarct size in patients with diabetes and acute ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Keywords: metformin, myocardial injury, ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction

Introduction

The American Heart Association considers diabetes to be a “major controllable risk factor for cardiovascular disease [CVD].”1 In addition to lifestyle changes, pharmacological therapeutic options including oral hypoglycemic agents are being actively investigated to determine their potential impact on CVD‐related death independent of their glucose‐lowering effects. To date, only metformin has shown promising results.2, 3, 4, 5, 6

Metformin is associated with lower mortality, both total and cardiovascular.7 Metformin seems to reduce myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury in animal studies8 and in humans based on a few preliminary studies9, 10; however, there is controversy regarding the possible cardioprotective effect of metformin. Few recent studies have specifically investigated the relationship between metformin use and myocardial infarction (MI). In a 2013 retrospective analysis, Zhao et al found that chronic pretreatment with metformin was associated with the reduction of the no‐reflow phenomenon in patients with diabetes mellitus after primary angioplasty for acute MI.9 In a 2014 retrospective cohort study, Lexis et al sought to investigate the association between metformin use and MI size in patients presenting with an acute MI.10 The researchers found that the use of metformin treatment was an independent predictor of smaller MI size.10 Nevertheless, Abualsuod et al found in a chart review study that the use of metformin in patients with diabetes was not associated with improvements in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) despite being related to both 30‐day and 12‐month all‐cause mortality.11 This finding suggests that metformin may be beneficial without directly influencing LVEF. In a prospective trial of metformin for ST‐segment elevation MI (STEMI) in nondiabetic patients, Lexis et al also failed to show a beneficial effect of metformin on LVEF after 4‐month follow‐up.12

Despite the encouraging findings showing that metformin use is associated with a lower risk of CVD‐related mortality, only a few studies with human participants have specifically investigated the relationship between metformin use and myocardial infarct size.9, 10, 11, 13, 14 We sought to use propensity score analysis to investigate the association between metformin use and infarct size prior to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients with diabetes presenting with STEMI.

Methods

Data Source

A retrospective cohort study of patients with diabetes (types 1 and 2) presenting with STEMI was conducted at 2 large tertiary academic medical centers in the New York metropolitan area. After institutional review board approval (14‐122A), data were extracted from the American College of Cardiology National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) covering the period from January 1, 2010, through December 31, 2013. The NCDR was developed in 1997 to capture reliable clinical, process‐of‐care, and outcomes data for patients undergoing coronary angiography and PCI in the United States, enabling practitioners to explore strategies for improving cardiovascular care.15, 16 The registry contains >250 data fields including patient medical history, risk factors, demographics, hospital presentation, initial cardiac status, procedural description, laboratory results, medication regimens, and in‐hospital outcomes.15 The registry contains ≈12 million records from 1577 institutions in the United States from 1998 to the present.15 Prior to propensity score matching (PSM), there were 208 metformin and 285 nonmetformin patients who met the eligibility criteria for this study. The final sample size after PSM was 274 participants (137 metformin and 137 nonmetformin patients).

Study Population and Selection Criteria

All patients were aged ≥18 years with known diabetes (defined by a history of diabetes diagnosed by a physician or fasting blood glucose >7 mmol/L or 126 mg/dL, regardless of duration of disease or need for glucose‐lowering medications) and presented with STEMI or STEMI equivalent (characterized by the presence of both electrocardiogram evidence and cardiac biomarker criteria). Data for all patients in this study were extracted from the NCDR CathPCI Registry version 4.4. Data on use of metformin, antiplatelet agents, and statin therapy prior to hospitalization were extracted by manual review of electronic health records for each patient.

Exposure of Interest

The exposure of interest was metformin use prior to STEMI. Metformin therapy prior to STEMI was defined as the documentation of a prescription for metformin at a dose of ≥250 mg per day that was in effect on the day prior to admission, as obtained from patients’ electronic home medication reconciliation order sheets.

Variables

Preprocedure cardiac biomarkers were recorded, including creatine kinase–myocardial band (CKMB) and troponin T measurements. These laboratory tests were drawn at our facilities and excluded point‐of‐care or bedside testing, with the target value being the last value between arrival and current procedure prior to PCI. Discharge LVEF (DCLVEF) after PCI was collected as well as postprocedure CKMB and troponin T peak values (within the interval of 6 to 24 hours after PCI with the target value being the highest value between 6 and 24 hours after the current procedure). Other variables collected included sex, body mass index, race, history of smoking, hypertension, dyslipidemia, prior MI, use of antianginal medications, antiplatelet agents, statin therapy, family history of coronary artery disease, prior PCI, prior heart failure, coronary artery bypass grafting, CVD, peripheral arterial disease, chronic lung disease, left ventricular systolic dysfunction, time from symptom onset to PCI (in hours), cardiogenic shock at presentation, and current anterior infarct.

Propensity Score Matching

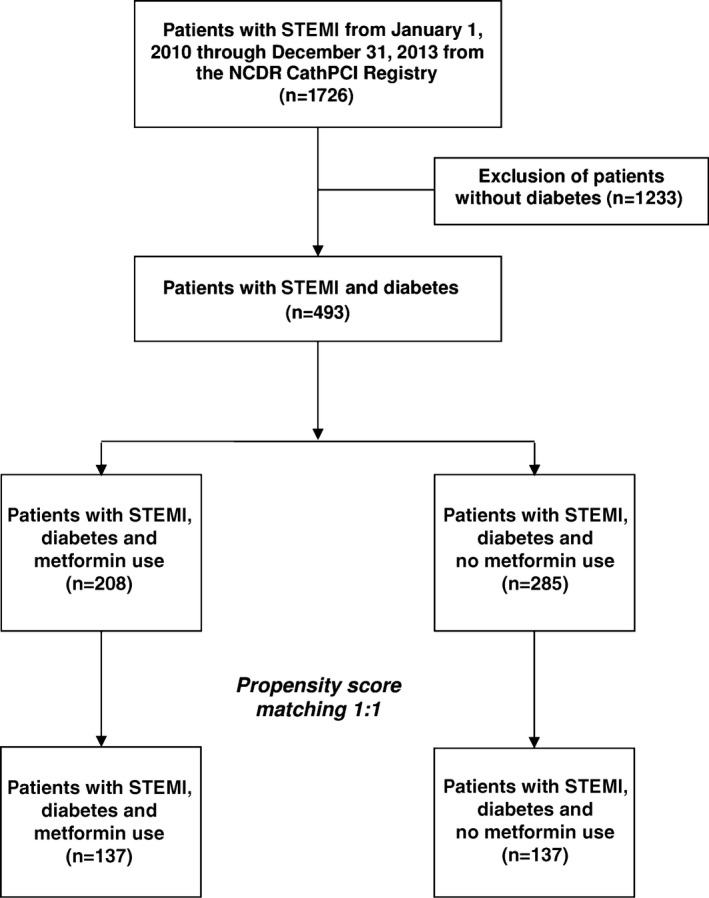

Given that this was a retrospective cohort study and not a randomized trial, it was necessary to achieve comparability of the metformin (intervention) and nonmetformin (control) groups with regard to potential confounding variables. This was accomplished using PSM (Figure).17 The following variables, chosen from the CathPCI Registry, were used to compute the propensity score for each patient: sex, race, smoking history, hypertension, dyslipidemia, prior MI, antianginal medication, antiplatelets, statin, family history of coronary artery disease, prior PCI, body mass index, time from symptom onset to PCI (in hours), and anterior infarct. In addition, a composite predictor variable was used that indicated the presence of at least 1 of the following conditions: prior heart failure, coronary artery bypass grafting, prior CVD, prior peripheral arterial disease, chronic lung disease, left ventricular systolic dysfunction, and cardiogenic shock. PSM was accomplished using the SAS macro OneToManyMTCH.18

Figure 1.

Propensity score matching flow diagram. NCDR indicates National Cardiovascular Data Registry; STEMI, ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction.

The standardized difference statistic (D, expressed as a percentage) was used to evaluate comparability of the 2 groups on each confounding variable before and after PSM.19 Comparability of the 2 groups with respect to the potential confounders before matching (n=208 metformin, n=285 controls) and after matching (n=137 metformin, n=137 controls) was also evaluated using descriptive statistics; the 2‐sample t test for continuous variables; and the chi‐square test or Fisher exact test, as deemed appropriate, for categorical variables. Summary statistics before matching (Table 1) and after matching (Table 2) were reported as frequency (percentage) for categorical data and as mean and SD and median (25th, 75th percentiles) for continuous data.

Table 1.

Comparability of the Groups Before Matching

| Variable | Nonmetformin (n=285) | Metformin (n=208) | P Value | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 196 (68.8%) | 147 (70.7%) | 0.651 | 4.1 |

| Race (white) | 132 (46.3%) | 88 (42.3%) | 0.377 | 8.1 |

| Smoker | 53 (18.6%) | 51 (24.5%) | 0.111 | 14.4 |

| Hypertension | 246 (86.3%) | 174 (83.7%) | 0.411 | 7.4 |

| Dyslipidemia | 205 (71.9%) | 159 (76.4%) | 0.260 | 10.3 |

| Prior MI | 48 (16.8%) | 21 (10.1%) | 0.033 | 19.8 |

| Antianginal medication | 152 (53.3%) | 90 (43.3%) | 0.027 | 20.2 |

| Antiplatelets | 131 (46.0%) | 83 (39.9%) | 0.180 | 12.2 |

| Statin | 133 (46.7%) | 127 (61.1%) | 0.002 | 29.1 |

| Family history of CAD | 29 (10.2%) | 23 (11.1%) | 0.752 | 2.9 |

| Prior PCI | 58 (20.4%) | 37 (17.8%) | 0.465 | 6.7 |

| BMIa |

29.3±6.0 [median 28.4 (25.1, 32.6)] |

30.3±7.5 [median 28.3 (25.8, 32.4)] |

0.424 | 14.2 |

| Time from symptom onset to PCI, hoursa |

9.6±14.1 [median 4.1 (2.6, 10.2)] |

8.1±12.4 [median 3.8 (2.3, 7.9)] |

0.231 | 11.1 |

| Anterior infarct | 99 (35.1%) | 60 (30.3%) | 0.271 | 10.2 |

| Combined predictor variableb | 93 (32.6%) | 33 (15.9%) | <0.0001 | 39.8 |

| Prior HF | 29 (10.2%) | 9 (4.3%) | 0.016 | — |

| Prior CABG | 19 (6.7%) | 6 (2.9%) | 0.059 | — |

| Prior CVD | 20 (7.0%) | 11 (5.3%) | 0.435 | — |

| Prior PAD | 21 (7.4%) | 7 (3.4%) | 0.059 | — |

| Chronic lung disease | 12 (4.2%) | 5 (2.4%) | 0.278 | — |

| Cardio LVSD | 14 (4.9%) | 6 (2.9%) | 0.260 | — |

| Cardiogenic shock | 16 (5.6%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0.002 | — |

BMI indicates body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD, coronary artery disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HF, heart failure; LVSD, left ventricular systolic dysfunction; MI, myocardial infarction; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

All categorical data are reported as frequency (percentage). The 2 continuous variables, BMI and time from symptom onset to PCI, are reported as mean±SD and median (25th, 75th percentiles).

Only the combined predictor variable was used in propensity score matching. The 7 components of this variable are shown for informational purposes only.

Table 2.

Comparability of the Groups After Matching

| Variable | Nonmetformin (n=137) | Metformin (n=137) | P Value | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 87 (63.5%) | 89 (65.0%) | 0.801 | 3 |

| Race (white) | 62 (45.3%) | 64 (46.7%) | 0.808 | 2.9 |

| Smoker | 27 (19.7%) | 30 (21.9%) | 0.655 | 5.4 |

| Hypertension | 117 (85.4%) | 112 (81.8%) | 0.415 | 9.8 |

| Dyslipidemia | 102 (74.5%) | 97 (70.8%) | 0.498 | 8.2 |

| Prior MI | 22 (16.1%) | 18 (13.1%) | 0.494 | 8.2 |

| Antianginal medication | 61 (44.5%) | 62 (45.3%) | 0.903 | 1.5 |

| Antiplatelets | 62 (45.3%) | 62 (45.3%) | 1.000 | 0 |

| Statin | 71 (51.8%) | 71 (51.8%) | 1.000 | 0 |

| Family history of CAD | 12 (8.8%) | 15 (11.0%) | 0.543 | 7.3 |

| Prior PCI | 28 (20.4%) | 30 (21.9%) | 0.767 | 3.6 |

| BMIa |

30.4±6.4 [median 29.2 (25.8, 33.3)] |

30.2±7.1 [median 28.2 (25.8, 32.4)] |

0.407 | 2.9 |

| Time from symptom onset to PCI, hoursa |

1.6±1.1 [median 1.4 (0.9, 2.3)] |

1.5±1.0 [median 1.4 (0.8, 2.1)] |

0.570 | 2.2 |

| Anterior infarct | 48 (35.0%) | 44 (32.1%) | 0.609 | 6.2 |

| Combined predictor variableb | 20 (14.6%) | 20 (14.6%) | 1.000 | 0 |

| Prior HF | 4 (2.9%) | 7 (5.1%) | 0.356 | — |

| Prior CABG | 4 (2.9%) | 2 (1.5%) | 0.684c | — |

| Prior CVD | 2 (1.5%) | 9 (6.6%) | 0.031 | — |

| Prior PAD | 3 (2.2%) | 4 (2.9%) | 1.000c | — |

| Chronic lung disease | 5 (3.7%) | 4 (2.9%) | 1.000c | — |

| Cardio LVSD | 4 (2.9%) | 5 (3.7%) | 1.000c | — |

| Cardiogenic shock | 4 (2.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.122c | — |

BMI indicates body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD, coronary artery disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HF, heart failure; LVSD, left ventricular systolic dysfunction; MI, myocardial infarction; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

All categorical data are reported as frequency (percentage). The 2 continuous variables, BMI and time from symptom onset to PCI, are reported as mean±SD and median (25th, 75th percentiles).

Only the combined predictor variable was used in propensity score matching. The 7 components of this variable are shown for informational purposes only.

Fisher exact test.

It should be noted that it is common for the sample size prior to PSM to be quite large compared with the resulting sample size after creating matched pairs. This is also the case in most epidemiological studies in which variable‐specific matching is used.

Primary Outcome

The primary study outcome variable was myocardial infarct size as demonstrated by the peak levels of cardiac biomarkers and DCLVEF after the STEMI event. In cases in which CKMB (and similarly for troponin T) was measured both before and after the PCI, the larger of the 2 measurements was used to capture the worst possible cardiac tissue injury. Peak levels of cardiac biomarkers (CKMB and troponin T) and LVEF after acute MI have been shown to have a strong correlation with myocardial infarct size and scar tissue in humans.20, 21

Statistical Analyses

Comparisons of the metformin and control groups were carried out using methods for paired continuous data. For CKMB and troponin T, the difference between metformin and control was calculated as the arithmetic difference (metformin minus control). The paired arithmetic difference was normally distributed and was analyzed using the paired t test and associated 95% CIs.

Confidence intervals for the metformin‐minus‐control arithmetic difference are presented in the usual way (Table 3). A result was considered statistically significant at the P<0.05 level. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc).

Table 3.

Matched Pairs Analyses of Primary Outcome Variables

| Metformin | Nonmetformin | Differencea and 95% CI for Difference | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CKMB (n=136 pairs) | 149.6±129.0 (median 99.0) | 167.6±180.7 (median 92.6) | −18.1 (−55.0 to 18.8) | 0.561 |

| Troponin T (n=135 pairs) | 5.7±4.9 (median 3.9) | 6.8±9.4 (median 4.1) | −1.1 (−2.8 to 0.5) | 0.410 |

| DCLVEF (n=127 pairs) | 43.5±11.1 (median 45.0) | 42.8±11.6 (median 45.0) | 0.7 (−2.2 to 3.6) | 0.987 |

Data were analyzed using the paired t test. CKMB indicates creatine kinase–myocardial band; DCLVEF, discharge left ventricular ejection fraction.

A positive (negative) difference indicates a larger (smaller) value for the metformin group.

Results

Of the 15 individual and composite predictor confounding variables, 10 had poor standardized difference scores (ie, >10%) prior to PSM. After PSM, there were 137 pairs of metformin and control patients. All 15 confounding variables had acceptable D scores (ie, <10%), indicating that the matching procedure was efficient in creating balance between the 2 groups. Tables 1 and 2 show the comparability statistics before and after PSM, respectively, for each of the potential confounding variables.

Although the analysis based on PSM is the focus of this study, it may be of interest to note that a direct, unadjusted, unmatched comparison of the 208 metformin patients and 285 controls resulted in no significant differences with respect to CKMB, troponin T, or DCLVEF.

Of all 1726 STEMI cases reviewed, 493 patients had diabetes (28.5%), with 208 (42.1%) metformin users and 285 nonusers. Matched pairs analysis yielded 137 cases per group. The arithmetic difference between the metformin and nonmetformin groups was −18.1 ng/mL (95% CI −55.0 to 18.8; P=0.56) for total peak serum CKMB and −1.1 ng/mL (95% CI −2.8 to 0.5; P=0.41) for troponin T. Median DCLVEF in both groups was 45. The arithmetic difference of DCLVEF between metformin and nonmetformin users was 0.7% (95% CI −2.2 to 3.6; P=0.98).The matched pairs comparison of the 137 metformin and control patients showed no significant differences with respect to CKMB, troponin T, or DCLVEF (Table 3), with P values ranging from 0.410 to 0.987. The confidence interval for DCLVEF is narrow, allowing the conclusion that there is no appreciable difference in this outcome between the 2 groups.

Discussion

The major objective of our study was to investigate the association between metformin use prior to PCI and myocardial injury in patients with diabetes and STEMI. In our propensity score matched study, the results showed no significant differences with respect to CKMB, troponin T, and DCLVEF.

Numerous studies have shown that metformin is associated with a lower risk for CVD‐related complications and death.7, 13, 22, 23, 24, 25 In 1998, a study on the effects of intensive blood glucose control with metformin on macrovascular and microvascular complications and mortality in overweight patients with diabetes found that those receiving metformin had risk reduction of 36% for all‐cause mortality and 46% for diabetes‐related death.7 Similarly, in 2002, Johnson et al documented that metformin therapy was associated with lower all‐cause and cardiovascular mortality compared with sulfonylurea monotherapy.22 In a 2008 systematic review, based on 40 controlled trials, Selvin et al found that metformin treatment was associated with a lower cardiovascular mortality risk compared with other oral glucose‐lowering medications or a placebo.23

In a post hoc analysis from the Diabetes Mellitus Insulin–Glucose Infusion in Acute Myocardial Infarction (DIGAMI) 2 trial, Melbin et al found that metformin was associated with a lower mortality rate.13 In 2011, a nationwide Danish study explored the relationship between mortality and cardiovascular risk associated with different insulin secretagogues compared with metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes with or without a previous MI.24 Monotherapy with metformin resulted in decreased mortality risk compared with glimepiride, glibenclamide, glipizide, and tolbutamide. In a randomized double‐blind placebo‐controlled trial investigating the effect of metformin compared with glipizide on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and CVD, metformin treatment led to a significantly lower number of major cardiovascular events compared with glipizide at 5 years (7 versus 14 deaths, respectively).25 The GLP‐1 receptor agonist exenatide has been demonstrated to be cardioprotective in both animal studies26 and clinical trials.27, 28, 29 Conversely, sulphonylurea antidiabetic drugs seem to disrupt cardioprotection through inhibition of ATP‐dependent potassium channels.30

Animal studies suggest that metformin induces cardioprotection against ischemia and reperfusion injury, independently from its glucose‐lowering effect, by limiting myocardial infarct size and remodeling.8, 31, 32, 33 In a 2008 study conducted in rats, a single metformin dose protected the myocardium against experimentally induced ischemia 24 hours after administration of the drug, with an acute increase in myocardial adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase activity and a significant reduction of myocardial infarct size.31 More recently, in a 2013 study, chronic metformin administration once again resulted in cardioprotection against infarction in the form of myocardial resistance to ischemia–reperfusion injury in diabetic and nondiabetic rats.32 This research suggests that metformin positively affects mitochondrial structure through adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase activation and proliferator‐activated receptor‐γ coactivator (PGC‐1α) by restricting the occurrence of myocardial injury from cardiovascular events.

In humans, a recent retrospective cohort study sought to investigate the association between metformin use and MI size in patients presenting with an acute MI.10 The researchers divided patients with diabetes into metformin versus nonmetformin groups and estimated MI size using peak values of serum creatine kinase, CKMB, and troponin T.10 After adjustment for age, sex, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction flow after PCI, and previous MI, Lexis et al found that the use of metformin treatment remained an independent predictor of smaller MI size10; however, in a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study in nondiabetic participants, also conducted by Lexis et al, the use of metformin compared with placebo did not result in improved LVEF after 4 months.12 The negative outcome results shown by Lexis et al in their trial could have been due to the study procedure, which involved providing patients with metformin after the event of STEMI and PCI.

Our study was specifically designed to investigate the association of metformin and myocardial infarct size in patients with diabetes on metformin therapy prior to the event. We used PSM to control for 15 potential confounding/composite variables including sex, race, smoking history, hypertension, dyslipidemia, prior MI, antianginal medication, antiplatelets, statin, family history of coronary artery disease, prior PCI, body mass index, time from symptom onset to PCI, anterior infarct, and a combined predictor variable (prior heart failure, coronary artery bypass grafting, CVD, peripheral arterial disease, chronic lung disease, cardiovascular left ventricular systolic dysfunction, and cardiogenic shock).

The “negative” results in our study need to be interpreted in the context of whether these might be type II errors. A way to address this is by examining the associated confidence intervals as follows: Given the narrow confidence interval for DCLVEF (95% CI −2.2 to 3.6; P=0.987) and even at the extremes of this confidence interval, there appears to be no clinically significant difference, which allows us to conclude that there is no appreciable difference in DCLVEF between the metformin and nonmetformin groups. The same can be said of troponin T because its confidence interval (95% CI −2.8 to 0.5; P=0.41) also suggests that, at the extremes, there is no clinically appreciable difference.

With regard to difference in CKMB, the wider confidence interval and the lower and upper end points (95% CI −55.0 to 18.8) suggest that group differences could be clinically meaningful. Consequently, the observed lack of group difference for CKMB may be inconclusive (ie, type II error).

The main limitation of this study is that it takes into account only final infarct size, not the myocardial salvage area. We found that the infarct size was similar in both groups, but there are 2 confounding factors with this result: variations in coronary anatomy and the possibility that coronary occlusions were more proximal in 1 group than in the other group, so the area at risk (the ischemic area) was larger, and that justifies a larger infarct size. We cannot rule out that metformin was cardioprotective, but the metformin group had a larger ischemic area from the very beginning. Another limitation of our study is that we did not collect data on the duration of metformin use, the specific doses, or patients’ adherence to their medication regimens. If patients started metformin the previous day, they would still be achieving plasma steady‐state levels; however, not knowing the specific dose (metformin may be cardioprotective at specific doses) and whether they were noncompliant with the treatment limits our study results. An additional limitation is that we could not differentiate between patients with type 1 and 2 diabetes in our sample because the CathPCI Registry groups all patients with diabetes into 1 category; however, metformin is the first‐line drug for type 2 diabetes and typically is not prescribed to patients with type 1 diabetes, who usually are insulin dependent. A last limitation of our study is that we could use data from only 2 of our institutions. NCDR compiles data from 1577 participating institutions but provides access to raw data for research only to the institution from which the data originated. Data from other institutions are provided in the form of national risk‐adjusted benchmark reports. In addition, NCDR does not provide data on use of metformin; in our study, this was extracted from manual review of individual patients’ electronic medical records.

Although studies have previously documented beneficial cardioprotective effects of metformin, the exact mechanism and presence of this effect in humans remains elusive. It appears that infarct size in the setting of myocardial injury is not associated with metformin use in the present era of primary PCI. Further prospective controlled trials may help elucidate the effect of metformin with respect to cardioprotection and allow for the enhanced care of patients experiencing an acute coronary event.

Disclosures

None.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e002314 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002314)

These data were presented in an abstract at the American College of Cardiology 64th annual scientific session, March 14, 2015, in San Diego, California.

References

- 1. American Heart Association . Cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Available at: http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/Diabetes/WhyDiabetesMatters/%20Cardiovascular-Disease-Diabetes_UCM_313865_Article.jsp. Accessed August 31, 2014.

- 2. Lincoff AM, Wolski K, Nicholls SJ, Nissen SE. Pioglitazone and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta‐analysis of randomized trials. J Am Med Assoc. 2007;298:1180–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nissen SE, Wolski K. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2457–2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nissen SE, Wolski K. Rosiglitazone revisited: an updated meta‐analysis of risk for myocardial infarction and cardiovascular mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1191–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ghotbi AA, Køber L, Finer N, James WPT, Sharma AM, Caterson I, Coutinho W, Van Gaal LF, Torp‐Pedersen C, Andersson C. Association of hypoglycemic treatment regimens with cardiovascular outcomes in overweight and obese subjects with type 2 diabetes a substudy of the SCOUT trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:3746–3753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roumie CL, Hung AM, Greevy RA, Grijalva CG, Liu X, Murff HJ, Elasy TA, Griffin MR. Comparative effectiveness of sulfonylurea and metformin monotherapy on cardiovascular events in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:601–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Turner R, Holman R, Stratton I, Cull C, Matthews D, Manley S, Frighi V, Wright D, Neil A, Kohner E. Effect of intensive blood‐glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). Lancet. 1998;352:854–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Calvert JW, Gundewar S, Jha S, Greer JJ, Bestermann WH, Tian R, Lefer DJ. Acute metformin therapy confers cardioprotection against myocardial infarction via AMPK‐eNOS–mediated signaling. Diabetes. 2008;57:696–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhao JL, Fan CM, Yang YJ, You SJ, Gao X, Zhou Q, Pei WD. Chronic pretreatment of metformin is associated with the reduction of the no‐reflow phenomenon in patients with diabetes mellitus after primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Ther. 2013;31:60–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lexis CP, Wieringa WG, Hiemstra B, van Deursen VM, Lipsic E, van der Harst P, van Veldhuisen DJ, van der Horst IC. Chronic metformin treatment is associated with reduced myocardial infarct size in diabetic patients with ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2014;28:163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abualsuod A, Rutland JJ, Watts TE, Pandat S, Delongchamp R, Mehta JL. The effect of metformin use on left ventricular ejection fraction and mortality post‐myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2015;29:265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lexis CP, van der Horst IC, Lipsic E, Wieringa WG, de Boer RA, van den Heuvel AF, van der Werf HW, Schurer RA, Pundziute G, Tan ES. Effect of metformin on left ventricular function after acute myocardial infarction in patients without diabetes: the GIPS‐III randomized clinical trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2014;311:1526–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mellbin L, Malmberg K, Norhammar AF, Wedel H, Ryden L; Investigators D . Prognostic implications of glucose‐lowering treatment in patients with acute myocardial infarction and diabetes: experiences from an extended follow‐up of the diabetes mellitus insulin–glucose infusion in acute myocardial infarction (DIGAMI) 2 study. Diabetologia. 2011;54:1308–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Paneni F, Costantino S, Cosentino F. Metformin and left ventricular remodeling after acute myocardial infarction: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. G Ital Cardiol (Rome). 2015;16:225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moussa I, Hermann A, Messenger JC, Dehmer GJ, Weaver WD, Rumsfeld JS, Masoudi FA. The NCDR CathPCI Registry: a US national perspective on care and outcomes for percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart. 2013;99:297–303. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl‐2012‐303379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. National Cardiovascular Data Registry . CathPCI Registry for diagnostic cardiac catheterizations and percutanious coronary interventions. Available at: https://www.ncdr.com/webncdr/cathpci/. Accessed October 3, 2014.

- 17. Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score. J Am Stat Assoc. 1984;79:516–524. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Parsons LS. Performing a 1:N case‐control match on propensity score. Proceedings of the 29th Annual SAS Users Group International Conference. May 9‐12, 2004. Montréal, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Austin PC. Assessing balance in measured baseline covariates when using many‐to‐one matching on the propensity‐score. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17:1218–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ingkanisorn WP, Rhoads KL, Aletras AH, Kellman P, Arai AE. Gadolinium delayed enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance correlates with clinical measures of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:2253–2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chia S, Senatore F, Raffel OC, Lee H, Frans JT, Jang I‐K. Utility of cardiac biomarkers in predicting infarct size, left ventricular function, and clinical outcome after primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;1:415–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johnson JA, Majumdar SR, Simpson SH, Toth EL. Decreased mortality associated with the use of metformin compared with sulfonylurea monotherapy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2244–2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Selvin E, Bolen S, Yeh H‐C, Wiley C, Wilson LM, Marinopoulos SS, Feldman L, Vassy J, Wilson R, Bass EB. Cardiovascular outcomes in trials of oral diabetes medications: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2070–2080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schramm TK, Gislason GH, Vaag A, Rasmussen JN, Folke F, Hansen ML, Fosbøl EL, Køber L, Norgaard ML, Madsen M. Mortality and cardiovascular risk associated with different insulin secretagogues compared with metformin in type 2 diabetes, with or without a previous myocardial infarction: a nationwide study. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1900–1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hong J, Zhang Y, Lai S, Lv A, Su Q, Dong Y, Zhou Z, Tang W, Zhao J, Cui L. Effects of metformin versus glipizide on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1304–1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Timmers L, Henriques JP, de Kleijn DP, DeVries JH, Kemperman H, Steendijk P, Verlaan CW, Kerver M, Piek JJ, Doevendans PA. Exenatide reduces infarct size and improves cardiac function in a porcine model of ischemia and reperfusion injury. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:501–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lønborg J, Vejlstrup N, Kelbæk H, Bøtker HE, Kim WY, Mathiasen AB, Jørgensen E, Helqvist S, Saunamäki K, Clemmensen P. Exenatide reduces reperfusion injury in patients with ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1491–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lønborg J, Kelbæk H, Vejlstrup N, Bøtker HE, Kim WY, Holmvang L, Jørgensen E, Helqvist S, Saunamäki K, Terkelsen CJ. Exenatide reduces final infarct size in patients with ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction and short‐duration of ischemia. Circulation. 2012;5:288–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Woo JS, Kim W, Ha SJ, Kim JB, Kim S‐J, Kim W‐S, Seon HJ, Kim KS. Cardioprotective effects of exenatide in patients with ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention results of exenatide myocardial protection in revascularization study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:2252–2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Meier J, Gallwitz B, Schmidt W, Mügge A, Nauck M. Is impairment of ischaemic preconditioning by sulfonylurea drugs clinically important? Heart. 2004;90:9–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Solskov L, Løfgren B, Kristiansen SB, Jessen N, Pold R, Nielsen TT, Bøtker HE, Schmitz O, Lund S. Metformin induces cardioprotection against ischaemia/reperfusion injury in the rat heart 24 hours after administration. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;103:82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Whittington HJ, Hall AR, McLaughlin CP, Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM, Mocanu MM. Chronic metformin associated cardioprotection against infarction: not just a glucose lowering phenomenon. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2013;27:5–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Paiva MA, Rutter‐Locher Z, Gonçalves LM, Providência LA, Davidson SM, Yellon DM, Mocanu MM. Enhancing AMPK activation during ischemia protects the diabetic heart against reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H2123–H2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]