Abstract

Deubiquitination has emerged as an important mechanism of regulating DNA repair pathways. We recently reported that USP24 is a novel p53 deubiquitinase that stabilizes p53 upon DNA damage. USP24 is upregulated by DNA damaging agents and plays an important role in maintaining genome stability.

Keywords: USP24, deubiquitination, deubiquitinase, DNA damage response, p53

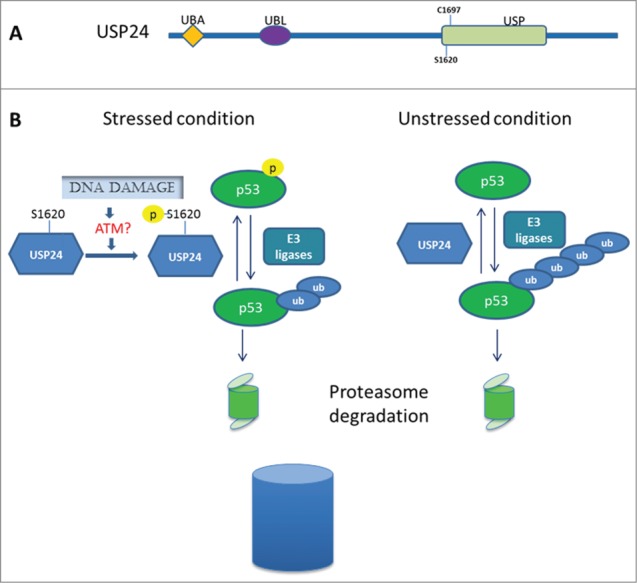

In recent years, key players in various DNA repair mechanisms have been shown to be ubiquitinated and deubiquitinated, and deubiquitinases (DUBs) have emerged as key factors in DNA repair pathways.1-5 DUBs oppose the action of the ubiquitin ligases by cleaving the isopeptide bond between lysine residues on target proteins and the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin. The DUB ubiquitin-specific protease 24 (USP24) is a 2,620-amino acid protein containing a ubiquitin-associated domain (UBA domain), a ubiquitin-like domain (UBL domain), and a ubiquitin-specific protease domain (USP domain) (Fig. 1A).6 Not much is known about the functions of USP24 in cells. USP24 was first discovered in our laboratory as a damage-specific DNA binding protein 2 (DDB2) interacting protein using the yeast 2-hybrid system.4 DDB2 plays a crucial role in the repair of ultraviolet (UV) radiation-induced DNA damage by the nucleotide excision repair pathway. Interestingly, genetic linkage studies indicated that the region containing the human USP24 gene is significantly correlated with Parkinson disease. Additionally, it was found that nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) plays an important role in controlling USP24 expression at the transcriptional level.7

Figure 1.

Role of USP24 in the DNA damage response. (A) Domains identified in USP24: UBA, ubiquitin-associated domain; UBL, ubiquitin like domain; USP, ubiquitin specific protease domain. The crucial cysteine 1697 of the protease domain and the putative ATM phosphorylation site serine 1620 are indicated. (B) Model depicting the role of USP24 in p53 stabilization. Deubiquitination of p53 by USP24 is required for p53 stabilization under both stressed and unstressed conditions. Upon DNA damage, USP24 is stabilized by ATM phosphorylation at S1620. Increased levels of USP24 lead to p53 stabilization/upregulation and subsequent activation of p53 downstream targets.

In a recently published article entitled “The Deubiquitinating Enzyme USP24 is a Regulator of the UV Damage Response”,6 we investigated the role of USP24 in the DNA damage response. In multiple cell lines, USP24 protein was found to be induced at 3 hours after UV irradiation, and RT-PCR assays showed that upregulation of USP24 did not occur at the transcriptional level. The upregulation of USP24 was blocked by the ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) inhibitor Ku55933 and by siRNA knockdown of ATM, suggesting that upregulation of USP24 is ATM dependent. We next set out to determine the ATM phosphorylation sites on USP24. As ATM specifically phosphorylates SQ/TQ motifs, we identified and mutated USP24 Serine 1620 to Alanine. The S1620A mutation abolished USP24 stabilization after DNA damage (unpublished data), suggesting that S1620 might be the ATM phosphorylation site responsible for USP24 stabilization. Moreover, we also showed that USP24 was induced by various DNA-damaging agents, including ionizing radiation, cisplatin, and hydrogen peroxide, indicating that the role of USP24 in the DNA damage response is not limited to UV irradiation.

p53 (TP53, best known as p53) is a very short-lived protein, being constantly degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. p53 is stabilized in response to cellular stress, such as UV irradiation, as a result of decreased degradation. When we depleted USP24 in HCT116 cells p53 failed to accumulate, suggesting that USP24 plays a role in UV-induced p53 stabilization. Moreover, we showed that the regulation of p53 activation by USP24 is not mediated by mouse double minute 2 homolog (Mdm2), its major E3 ligase. Since USP24 is a deubiquitinase, we speculated that p53 is a direct substrate of USP24. Indeed, we provided several lines of evidence to support this notion. First, we depleted USP24 using several USP24-specific siRNA and short hairpin RNA (shRNA) constructs and found that downregulation of USP24 decreased p53 protein levels but had no effect on p53 mRNA levels. Second, we examined the ability of purified USP24 protein to deubiquitinate p53 in a test tube and found that USP24 was able to cleave and remove the ubiquitin moiety from p53 in a dose-dependent manner. Third, co-immunoprecipitation assays showed that USP24 interacts with p53. Moreover, USP24 knockdown led to the appearance of new forms of polyubiquitinated p53 in the presence of the proteasome inhibitor MG132. Collectively, our data show that USP24 deubiquitinates p53, leading to stabilization of p53. Since USP24 is a functional cysteine protease with 3 domains (Fig. 1A), we transfected cells with wild-type USP24, ΔUBA mutant, and C1697A mutant constructs and showed that both the UBA domain and the catalytic residue cysteine 1697 are required for USP24 to deubiquitinate p53.

The effect of USP24 on p53 activation after UV damage raised the possibility that USP24 regulates p53-dependent apoptosis and genome stability. Both the TUNEL assay and Caspase-Glo 3/7 assay were used to demonstrate that USP24 knockdown affected the apoptotic response to UV irradiation. The induction of apoptosis by UV was accompanied by cleavage of poly(ADP)ribose polymerase (PARP). We showed that PARP cleavage was slower and attenuated in USP24-depleted cells. However, PARP cleavage after UV was not affected by USP24 depletion in p53−/− cells, suggesting that USP24 targets p53 to regulate UV-induced apoptosis. We next used the hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT) assay, a mammalian cell gene mutation test, to show that USP24 depletion resulted in significantly elevated mutation rates at the endogenous HPRT gene, implying an important role for USP24 in maintaining genome stability.

p53 is tightly regulated by dynamic ubiquitination and deubiquitination. p53 is ubiquitinated by MDM2 and several other E3 ligases8 and deubiquitinated by a number of DUBs, including USP7, USP10, USP11, USP29, USP42, OTUD1 (OTU deubiquitinase 1), and OTUD5.9 One may wonder why multiple DUBs are needed and how they are coordinated to ensure dynamic control of p53 stability and activity. There are several possible reasons for this: first, different DUBs might regulate the p53 pathway in response to different cellular stresses; second, different DUBs might work in different cellular compartments; and third, since p53 is such an important protein that is ubiquitinated by many different E3 ligases, different DUBs may be required to counteract p53 ubiquitination of different ubiquitin linkage topologies. Indeed, it is known that DUBs have different types of substrate cleavage activities—some generate free ubiquitin from linear substrate, some remove ubiquitin from post-translationally modified protein, and others edit polyubiquitin chains.10

A survey of the Catalog Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer (COSMIC) database shows that USP24 is frequently mutated in various human cancers.6 Since p53 is a well-known tumor suppressor that regulates cell proliferation and USP24 potentiates p53 function by deubiquitination, it is possible that USP24 also acts as a tumor suppressor. The process of p53 ubiquitination is highly dynamic and it is now clear that it can be reversed by the action of DUBs. Thus, targeting DUBs may have promising potential in cancer therapy.9 USP24 offers novel exciting perspectives in basic and translational research, and an improved mechanistic understanding of this deubiquitinase holds promise for improved cancer therapeutics.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH grant R01 ES017784 and grant R21 ES024882 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

References

- 1.Yuan J, Luo K, Zhang L, Cheville JC, Lou Z. USP10 regulates p53 localization and stability by deubiquitinating p53. Cell 2010; 140:384-96; PMID:20096447; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang D, Zaugg K, Mak TW, Elledge SJ. A role for the deubiquitinating enzyme USP28 in control of the DNA-damage response. Cell 2006; 126:529-42; PMID:16901786; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang J, Zhang P, Wei Y, Piao HL, Wang W, Maddika S, Wang M, Chen D, Sun Y, Hung MC, et al.. Deubiquitylation and stabilization of PTEN by USP13. Nat Cell Biol 2013; 15:1486-94; PMID:24270891; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb2874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang L, Lubin A, Chen H, Sun Z, Gong F. The deubiquitinating protein USP24 interacts with DDB2 and regulates DDB2 stability. Cell Cycle 2012; 11:4378-84; PMID:23159851; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.22688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacq X, Kemp M, Martin NM, Jackson SP. Deubiquitylating enzymes and DNA damage response pathways. Cell Biochem Biophys 2013; 67:25-43; PMID:23712866; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s12013-013-9635-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang L, Nemzow L, Chen H, Lubin A, Rong X, Sun Z, Harris TK, Gong F. The Deubiquitinating Enzyme USP24 Is a Regulator of the UV Damage Response. Cell Rep 2015; 10(2):140-7; PMID:25578727; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang K, Liu S, Wang J, Wu Y, Cai F, Song W. Transcriptional regulation of human USP24 gene expression by NF-kappa B. J Neurochem 2014; 128:818-28; PMID:24286619; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/jnc.12626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JT, Gu W. The multiple levels of regulation by p53 ubiquitination. Cell Death Differ 2010; 17:86-92; PMID:19543236; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cdd.2009.77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Arcy P, Wang X, Linder S. Deubiquitinase inhibition as a cancer therapeutic strategy. Pharmacol Therap 2014; 147:32-54; PMID:25444757; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Komander D, Clague MJ, Urbe S. Breaking the chains: structure and function of the deubiquitinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2009; 10:550-63; PMID:19626045; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm2731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]