ABSTRACT

We have recently identified receptor (TNFRSF)-interacting serine-threonine kinase 1 (RIPK1) as an oncogenic driver in melanoma in addition to its well-established role in controlling cell survival and death. Our studies show that RIPK1 promotes melanoma cell proliferation through a positive feedback loop of NFKB1-BIRC2/BIRC3-RIPK1 powered by autocrine tumor necrosis factor.

KEYWORDS: Cell death, cell proliferation, death receptor, melanoma, NF-κB, RIPK1

Abbreviations

- BIRC

baculoviral IAP repeat containing

- BRAF

B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase

- CASP8

caspase8, apoptosis-related cysteine peptidase

- CFLAR

CASP8 and FADD-like apoptosis regulator

- FADD

Fas (TNFRSF6)-associated via death domain

- IKBKG

inhibitor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells, kinase gamma

- NFKB1

nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells 1

- NFKBIA

nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, α

- NR2C2

nuclear receptor subfamily 2, group C, member 2

- NRAS

neuroblastoma RAS viral (v-ras) oncogene homolog

- RIPK1

receptor (TNFRSF)-interacting serine-threonine kinase 1

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- TAB

TGF-β activated kinase 1/MAP3K7 binding protein

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- TNFRSF1A

tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 1A

- TRADD

TNFRSF1A-associated via death domain

- TRAF2

TNF receptor-associated factor 2

Receptor (TNFRSF)-interacting serine-threonine kinase 1 (RIPK1) mediates both cell survival and death signaling and is emerging as an important determinant of cell fate in response to cellular stress.1 However, its possible contributions to cancer development and progression remain largely undefined, although increasing studies have shown that RIPK1 is involved in apoptosis and necrosis of cancer cells in response to various therapeutic drugs.2,3 We recently reported that RIPK1 functions as an oncogenic driver in human melanoma through activating nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells 1 (NFKB1, best known as NF-κB),4 thus shedding light on the potentially critical role of RIPK1 in the pathogenesis of cancer.

We were led to investigate the functional significance of RIPK1 in melanoma cells by the observation that the expression of RIPK1 was frequently elevated in melanomas compared to nevi. We further found that silencing of RIPK1 inhibited melanoma cell proliferation and retarded the growth of melanoma xenografts in vivo. Conversely, although RIPK1 overexpression induced apoptosis in a small proportion of melanoma cells, it enhanced proliferation in the remaining cells. Likewise, ectopic expression of RIPK1 enhanced the proliferation of primary melanocytes, triggering their anchorage-independent growth. Mechanistic studies showed that the proliferative effect of RIPK1 on melanoma cells and melanocytes was mediated by NF-κB activation. These results not only point to a role of RIPK1 in promoting the development and progression of melanoma, but also reveal that RIPK1 is responsible, at least in part, for the constitutive NF-κB activation that is commonly found at high levels in melanomas.5

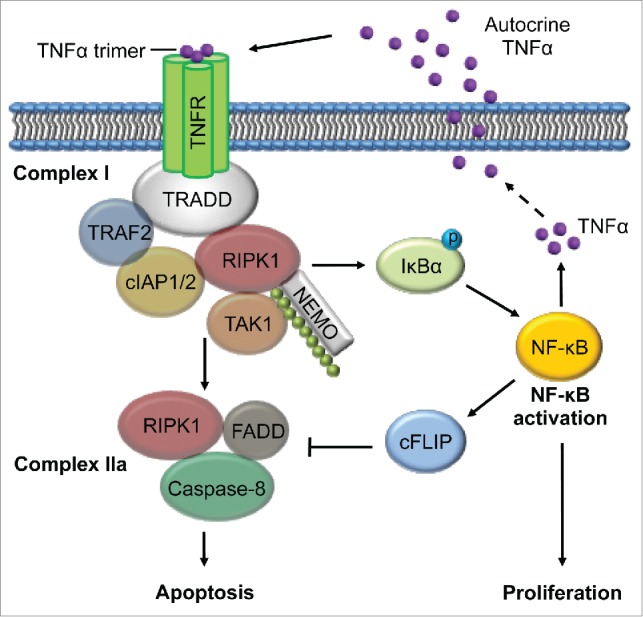

How is RIPK1 upregulated in melanoma cells? We analyzed the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset and found that DNA copy number gain occurred in 5.3% of melanomas, consistent with our results in a small panel of melanoma cell lines and fresh melanoma isolates. This obviously could not fully account for the frequent upregulation of RIPK1 in melanomas. We next screened transcriptional, translational, and post-translational mechanisms that might be involved in the upregulation of RIPK1, and discovered that RIPK1 was constitutively polyubiquitinated with K63-linked ubiquitin chains, a modification known to stabilize the protein, in melanoma cells.6 Indeed, the E3 ligases baculoviral IAP repeat containing 2 (BIRC2, best known as cIAP1) and BIRC3 (best known as cIAP2) that polyubiquitinize RIPK1 at K63 were found to bind constitutively to RIPK1, and, as anticipated, pharmacologic or genetic inhibition of cIAPs reduced K63-linked polyubiquitination and the expression of RIPK1. Since cIAPs are transcriptional targets of NF-κB and RIPK1 mediates activation of NF-κB, it appears that a positive feedback loop of NF-κB-BIRC2/3-RIPK1 is essential for maintaining high levels of RIPK1 expression and NF-κB activation in melanoma cells (Fig. 1)

Figure 1.

NF-κB-cIAPs-RIPK1-dependent feed-forward signaling loop driven by autocrine TNFα. RIPK1 is constitutively ubiquitinated at K63 by BIRC2, and BIRC3 in Complex I, which also contains TRADD and TRAF2. The K63-linked ubiquitin chains serve as substrates for binding of NEMO and the complex of TAB2, TAB3, and TAK1, leading to phosphorylation of IκBα and subsequent activation of NF-κB, which promotes cell proliferation. NF-κB transcriptionally upregulates TNFα, which drives continuous recruitment of RIPK1 and cIAPs to Complex I through autocrine stimulation. TNFα also transcriptionally upregulates cIAPs to ensure ubiquitination and stabilization of RIPK1, CASP8, and cFLIP to protect against the apoptosis-inducing potential of TNFα in complex IIa that contains FADD and CASP8. BIRC2/3, baculoviral IAP repeat containing 2/3 (also known as cIAP1/2); CASP8, caspase8, apoptosis-related cysteine peptidase (also known as Caspase-8); cFLIP, FADD-like apoptosis regulator (CFLAR, best known as cFLIP); FADD, Fas (TNFRSF6)-associated via death domain; IκBα, nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, α (NFKBIA, best known as IκBα); NEMO, inhibitor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells, kinase gamma (IKBKG, best known as NEMO); NF-κB, nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells 1(NFKB1, best known as NF-κB); TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha; RIPK1, receptor (TNFRSF)-interacting serine-threonine kinase 1; TAB2/2;TGF-β activated kinase 1/MAP3K7 binding protein 2/3; TAK1, nuclear receptor subfamily 2, group C, member 2 (NR2C2, best known as TAK1); TNFR, tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 1A (also known as TNFRSF1A); TRADD, TNFRSF1A-associated via death domain; TRAF2, TNF receptor-associated factor 2.

We then went on to address a fundamental question: what powers the NF-κB- BIRC2/3-RIPK1 feedback loop in melanoma cells? In the case of exposure to tumor necrosis factor (TNF, best known as TNFα), RIPK1, along with the cIAPs, is recruited to complex I, where it is polyubiquitinated with K63-linked ubiquitin chains that in turn serve as substrates for the binding of inhibitor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells, kinase gamma (IKBKG, best known as NEMO), and the complex containing TGF-β activated kinase 1/MAP3K7 binding protein 2 (TAB2), TAB3, and nuclear receptor subfamily 2, group C, member 2 (NR2C2, best known as TAK1), leading to activation of NF-κB.1 By analogy, we wondered whether this feedback loop is driven by TNFa, which has long been known to be secreted by melanoma cells.7 Indeed, we demonstrated that autocrine TNFα played an important role in sustaining the NF-κB-BIRC2/2-RIPK1 feedback loop in melanoma cells. Given that TNFα is transcriptionally regulated by NF-κB, it appears that TNFα is an essential built-in component of the loop and plays a driving role in activation of the intracellular components (Fig. 1).

Cancer cells are commonly exposed to microenvironments characterized by chronic inflammation associated with high levels of TNFα.8,9 Although this promotes cancer cell survival and proliferation, conceivably by activating the NF-κB-BIRC2/2-RIPK1 feedback loop,1, 2 circumvention of the cell death-inducing potential of TNFα is a prerequisite. We showed that, despite its established role in TNFα-induced cell death when cIAPs are inhibited,2 RIPK1 played an important role in protection against the apoptosis induced by TNFα through NF-κB activation and subsequent upregulation of CASP8 and FADD-like apoptosis regulator (CFLAR, best known as cFLIP) in melanoma cells. These results identify cFLIP as a major effector of the NF-κB-BIRC2/3-RIPK1 feedback loop that enables melanoma cells to evade the death-inducing effect of TNFα (Fig. 1).

Because overexpression of RIPK1 induces apoptosis in a proportion of melanoma cells and melanocytes,4 it seems that the expression of RIPK1 must be under tight control so that its level remains constantly below a threshold to ensure avoidance of apoptosis. However, what determines this threshold remains unknown. Similarly, how expression of RIPK1 at high levels induces apoptosis of melanoma cells and melanocytes was left unresolved. Further studies are clearly needed to address these questions.

A highly clinically relevant finding of these studies is that RIPK1 upregulation is not associated with oncogenic activation of B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase (BRAF), or neuroblastoma RAS viral (v-ras) oncogene homolog (NRAS), suggesting that RIPK1 may cooperate with these oncogenic drivers in the pathogenesis of melanoma, and that inhibition of the proliferative effect of RIPK1 may curb melanoma growth irrespective of mutations in BRAF or NRAS, which often underlie resistance of melanoma to treatment. However, targeting RIPK1 has to be evaluated cautiously, as it is known to mediate cancer cell death induced by various cellular stresses.1-3 Nonetheless, our work has unveiled the dark side of RIPK1 by revealing its function as an oncogenic driver in melanoma. Whether RIPK1 has a similar role in other types of cancers remains to be clarified. Moreover, studies in RIPK1 transgenic animals are needed to define whether RIPK1 is an authentic oncogene in melanocytic cells.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This work was supported by Cancer Council NSW (RG 13–15 and RG 13–04), National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (APP1026458), and Hunter Medical Research Institute, Australia. CCJ and LJ are supported by Cancer Institute NSW Fellowships. XDZ is supported by a NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship.

References

- 1.Christofferson DE, Li Y, Yuan JY. Control of life-or-death decisions by RIP1 kinase. Annu Rev Physiol 2014; 76: 129-150; PMID:24079414; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021113-170259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang L, Du F, Wang X. TNF-alpha induces two distinct caspase-8 activation pathways. Cell 2008; 133: 693-703; PMID:18485876; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christofferson DE, Yuan JY. Necroptosis as an alternative form of programmed cell death. Curr Opin in Cell Biol 2010; 22: 263-68; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu XY, Lai F, Yan XG, Jiang CC, Guo ST, Wang CY, Croft A, Tseng H-Y, Wilmott JS, Scolyer RA, et al.. RIP1 kinase is an oncogenic driver in melanoma. Cancer Res 2015; 75(8):1736-48; PMID:25724678; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNulty SE, del Rosario R, Cen D, Meyskens FL Jr, Yang S. Comparative expression of NFkappaB proteins in melanocytes of normal skin vs. benign intradermal naevus and human metastatic melanoma biopsies. Pigm Cell Melanoma R 2004; 17: 173-80; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2004.00128.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertrand MJM, Milutinovic S, Dickson KM, Ho WC, Boudreault A, Durkin J, Gillard JW, Jaquith JB, Morris ST, Barker PA. cIAP1 and cIAP2 facilitate cancer cell survival by functioning as E3 ligases that promote RIP1 ubiquitination. Mol Cell 2008; 30: 689-700; PMID:18570872; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elias EG, Hasskamp JH, Sharma BK. Cytokines and growth factors expressed by human cutaneous melanma. Cancers 2010; 2: 794-808; PMID:24281094; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3390/cancers2020794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balkwill F. TNF-a in promotion and progression of cancer. Cancer Metast Rev 2006; 25: 409-416; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10555-006-9005-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Popa C, Netea MG, van Riel PL, van der Meer JW, Stalenhoef AF. The role of TNF-alpha in chronic inflammatory conditions, intermediary metabolism, and cardiovascular risk. J Lipid Res 2007; 48: 751-62; PMID:17202130; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1194/jlr.R600021-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]