Abstract

Purpose:

Comparison of the rates of posterior capsule rupture (PCR) associated with conventional versus a reverse method of teaching phacoemulsification.

Methods:

Trainees were taught conventional (start-to-finish) phacoemulsification beginning with an incision (tunnel construction) to capsulorhexis, sculpting, nucleus cracking, segment removal, cortex aspiration, intraocular lens implantation, and viscoelastic removal. In the reverse method, after incision and capsulorhexis, the trainees were progressively taught viscoelastic wash, cortex aspiration, segment removal, nucleus cracking, sculpting, and intraocular lens implantation. Trainees from a Tertiary Eye Care Centre were classified as beginners, for their first 30 cases and then trainees for their next 70 surgeries. Data were collected on posterior capsular rent and vitreous loss during each step of training.

Results:

Thirty-two ophthalmic surgeons learning phacoemulsification surgery on 609 cataracts cases were supervised by 3 trainers. Fifteen beginners performed 287 surgeries using the conventional method, and 17 beginners performed 322 surgeries with the reverse method. The incidence of PCR was 18/287 (6.2%) with the conventional method and 15/322 (4.6%) with the reverse method (P = 0.38). PCR occurred during cortex aspiration (8/287, 2.8%) and segment removal (5/287, 1.7%) in the conventional method. PCR occurred during nucleus cracking, segment removal, and cortex aspiration (4/322 surgeries for each step, 1.2%). In the follow, 70 cases (trainees) there was no difference in PCR with either method (4.7% vs. 4.3%, P = 0.705).

Conclusion:

Conventional and reverse method for training phacoemulsification were both safe in a supervised setting.

Keywords: Cataract Surgery, Intra-Operative Complication, Phacoemulsification, Surgical Training

INTRODUCTION

Small incision cataract surgery (SICS) with phacoemulsification is the technique of choice for cataract surgeons worldwide, especially in paid practice settings.1 Hence, learning the technique for phacoemulsification is mandatory for beginners as well as experienced cataract surgeons who have not adapted to this procedure. The advantages of phacoemulsification surgery include excellent potential visual outcome, small corneal incision, and the possibility to employ premium intraocular lenses.2,3 However, it is not easy to master the technique due to its steep learning curve.

The options used to learn phacoemulsification surgery vary from surgeon to surgeon. Some rely on self-learning methods such as videos of expert surgeons or request training from the vendor of phacoemulsification units who are more than willing to offer “tips” to beginners.4 Some get trained by practicing on animal eyes in a wet lab. Although this is a good opportunity to know the functioning of the machine, human eyes differ considerably from animal eyes. Due to the difference in the thickness of lens capsule and lack of a nucleus in the animal lens, phacoemulsification in animal eyes is not the same as human eyes.

In the most teaching centers, formal training provided to a beginner who learns the procedure under the supervision of an expert who intervenes only at if complications occur or the duration of surgery is too long.4,5,6 In a stepwise training program, phacoemulsification surgery is divided into various steps and proficiency in one step leads to next step under the guidance and supervision of an expert trainer.7 Some centers in the developed world use simulators.8,9 The road to SICS aided by phacoemulsification is said to be slippery with vitreous. Numerous studies of resident training focus on preserving the posterior capsule and limiting vitreous loss.7,10,11,12,13 A novel technique of “reverse” method of training, in which the final steps of the surgical technique are taught first, and the initial steps are taught last was attempted in Brazil.14 However, it has never been compared to the traditional “start to finish” supervised method of teaching phacoemulsification surgery. The aim of the study was to compare “start to finish” or conventional method to the reverse method of training with regards to posterior capsular rupture (PCR) in phacoemulsification surgery at a teaching institute.

METHODS

This study was conducted at the Lions National Association for the Blind (NAB) Eye Hospital, a Tertiary Referral and Teaching Center in Western Maharashtra, India. This institute hospital fellowship program and residency programs. The Ethical Committee of the hospital approved this study. The incidence of PCR depends on the level of skill of a surgeon; hence, surgeons learning phacoemulsification surgery in the institution were divided into two groups. Those who had done <30 cases of phacoemulsification surgery were considered “Beginners,” those who had 30-100 cases were considered “trainee.” The hospital has an in-house residency training and fellowship training program. It also has some doctors enrolling for short-term phacoemulsification training (30 days course). These were ophthalmologists who had done their residency a few years ago and had now joined to enhance their skills. “Beginners” were thus not novice surgeons who were performing cataract surgery for the 1st time but had some experience with manual SICS and were now upgrading their skills for phacoemulsification.

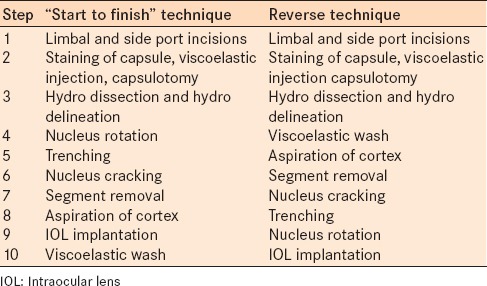

Table 1 outlines the 10-step division of phacoemulsification surgery. Chronology of steps in which the beginner learned surgery by “start to finish” or reverse method is demonstrated serially. From March 2008 to February 2009, beginners learned the “start to finish” method of teaching were considered Group A ("start to finish" or conventional), whereas from March 2009 to February 2010, beginners who learned using the reverse method were considered as Group B (reverse). The beginners in both groups were well versed with tunnel construction, continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis, and hydro dissection as they were performing manual SICS independently and with good results. The hospital authorities considered this criterion for beginning phacoemulsification training as the safest approach to transition to phacoemulsification, similar to other centers in India.5,15 Therefore, the first three steps for both the groups were same. Each beginner from their respective group was given 3-5 cases to learn a particular step from step number four. On acquiring adequate skill of the particular step they were allowed to move to the next step. Beginners from Group A learned the technique of phacoemulsification surgery using the conventional method. Beginners from Group B learned the reverse technique. The fourth step was removing (washing) viscoelastic material from the anterior chamber in a case that was being completed by the trainer. The fifth step was the aspiration of the cortex in a case where the trainer had already emulsified the nucleus. The sixth step involved emulsification of nucleus that was already cracked by the trainer. The seventh step involved the beginner being taught to crack the nucleus that was already trenched by the trainer. The eighth step involved teaching the beginner to trenching the nucleus and in ninth step nucleus rotation was taught. The final tenth step was in the bag implantation of poly-methyl-methacrylate lens with 5 mm optics. In the reverse method, steps 4-9 were exact reversals of the conventional method. After the 30th case, the surgeons were asked to perform surgery by the conventional method and were graduated to the trainee group. In both groups, the new step was preceded with the revision of the previous steps. Nucleus emulsification was taught with the “divide and conquer” method and irrigation-aspiration was taught as a bimanual method. Epinucleus removal was performed during the “cortex aspiration” step.

Table 1.

Order of steps of phacoemulsification taught

There are a variety of techniques for teaching phacoemulsification, the three supervising surgeons used the divide and conquered technique as they were most familiar with this method and considered it the easiest for the transition. Most trainees had some experience with manual SICS, and were proficient in tunnel construction and capsulorhexis and were familiar with the nuclear and advanced cortical cataracts that formed the bulk of the training cases. Suturing of the tunnel was performed if there was any uncertainty about the integrity of wound closure.

The outcome measure was the incidence of PCR in each group, and for “beginners” and “trainees.” Statistical analysis was performed with a two-by-two Chi-square test.

RESULTS

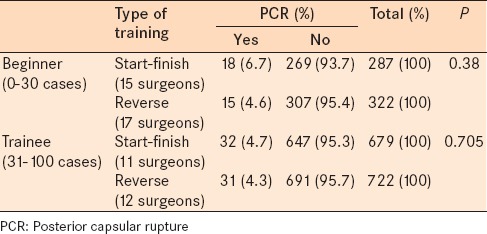

Thirty-two ophthalmologists learning phacoemulsification (the first 100 surgeries) participated in the study. Their average age was 30 years, and 17 (53.1%) were males. They were supervised by 3 trainers (2 female), each of whom had an experience of at least 8000 cataract surgeries, of at least 1000 were phacoemulsification cases. Table 2 presents the results of PCR with both methods.

Table 2.

Comparison of posterior capsular rupture by both methods of training

Fifteen beginners (first 30 cases) performed 287 surgeries by with the conventional method and had PCR occurred in 18 (6.2%) cases. Eleven of these beginners later performed 679 surgeries ("Trainee" group next 31-100 cases), and PCR occurred in 32 (4.7%) cases. Seventeen beginners performed 322 surgeries using the reverse method and PCR occurred in 15 (4.6%) cases (P = 0.38, Chi-square test for comparison between “beginners” of the two groups). Twelve surgeons taught with the reverse method later performed 722 phacoemulsification surgeries (“Trainee” group, next 31-100 cases) and PCR occurred in 31 (4.3%) cases (P = 0.705, Chi-square test for comparison between “trainees” of the two groups).

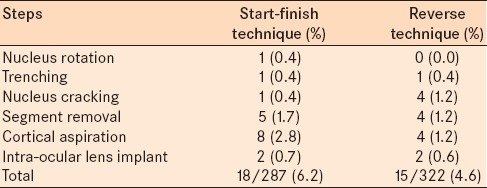

Table 3 presents that 18 cases had PCR with the conventional training method and PCR occurred while aspirating cortex in 8 (2.8%) cases followed by rupture during emulsification of nuclear fragments in 5 (1.7%) cases. Of 15 cases of PCR with the reverse training method, PCR occurred during nucleus fragmentation, emulsification, and cortical aspiration in 4 (1.2%) cases each.

Table 3.

Steps during surgery where posterior capsular rupture occurred

DISCUSSION

The transition from SICS or conventional extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE) to phacoemulsification is a steep learning curve.11,12 This is akin to new driver who initially has poor hand-foot-eye-brain coordination while learning to drive a car. Similarly, a lack of coordination is faced by beginner learning phacoemulsification surgery. The use of a foot switch is new to these individuals and requires some experience. Judicious use of ultrasound energy, vacuum, and flow rate is learned with experience. Therefore, PCR can occur at various steps of surgery. In the developed world, some centers use a virtual surgery simulator for training residents in phacoemulsification surgery. Those who were trained on simulators had less intraoperative complications and shorter learning curves.9 Hand and foot activated surgical tools in simulated ophthalmic surgery are also used to assess dexterity.8

In reverse training method, the transition to the new technique was gradual. A study assessing the difficulty of the various steps of phacoemulsification surgery reported an incidence of PCR of 9%.16 The most difficult steps were phacoemulsification of the nucleus and capsulorhexis.16 The steps considered most challenging that carried the greatest risks were emulsification of the nucleus and cortex aspiration. In the current study, these steps were taught towards the end of the training once the other steps were adequately performed. While washing viscoelastic as the first step of conversion, the trainee surgeon was familiarized with the use of the foot switch and gained experience in the nuances of foot pedal control. Cortex aspiration without use of ultrasound energy, emulsification of already divided nucleus, cracking of already divided nucleus helped build the confidence of the surgeons. Epinucleus aspiration was considered a part of the cortical aspiration step.

The reverse training method resulted in almost a third lower incidence of PCR in beginner group compared to conventional “start to finish” training method. In “trainee” groups (31-100 learning cases), the incidence of PCR was similar. In the cortical aspiration step, the incidence of PCR decreased more than 50% in the reverse method compared to conventional method. In nucleus cracking step, the incidence of PCR was >0.89% in reverse method compared to the conventional method. However, these differences were not statistically significant (two proportion Z-test). The decreased incidence of PCR could be due to the trainer surgeons performing the initial steps (e.g., continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis, hydro-dissection, and rotation of the nucleus) more diligently. The trainer surgeons were experienced and left a clean and clear field for the trainees to operate on, thus decreasing the chance of the capsular damage.

The “beginners” in the current study were already trained in SICS. However, they experienced difficulty in cortical aspiration and nucleus fragment emulsification likely due unfamiliarity with using a foot switch. Thomas observed two residents in early stage of learning phacoemulsification and noted an incidence of PCR of 10% although they were familiar with SICS.13

Hennig stated that in unsupervised learning, formal training, and stepwise formal training the incidence of PCR was 15%, 10%, and 4.8%, respectively; thus advocating stepwise formal training for beginner.4 Studies of complications during surgical residency training from Germany and USA reported an incidence of PCR of 3.8% and 3.1%, respectively during phacoemulsification training.7,10 Reports from Taiwan and USA evaluating the learning curve of phacoemulsification in resident surgeons reported an incidence of PCR of 4.9% and 5.1% respectively.11,12 The US study noticed that the incidence of PCR decreased from 5.1% to 1.9% after 80 surgeries indicating safety and efficiency improved with experience. Our study had comparable results although the “reverse” technique made the training safer in terms of PCR.

The Brazilian Council of Ophthalmology, in partnership with Alcon Brazil, used the reverse method to teach phacoemulsification surgery. The module used by Fischer et al. was slightly different where the progress of three 2nd -year resident surgeons was monitored at five “checkpoints.” The incidence of PCR in this study was 13.1%.14 India has a large pool of young ophthalmologists who need phacoemulsification training.17 The feedback from residency training programs showed that surgical training for residents was considered inadequate by many of the respondents.18 One reason is that the residency chief believed surgical teaching may compromise on the quality of patient care.19,20 Many young ophthalmologists, therefore, seek special phacoemulsification training after the completion of their residency and fellowship programs. The reverse method may offer a new, safer method of mastering phacoemulsification.

The limitations of this study include that nonrandomized design and that data from a single center are reported. A larger comparison with multiple centers would help refute or validate the relatively greater safety of the reverse method in preserving the posterior capsule. In addition, our “beginners” were surgeons with some experience in manual SICS and not residents performing cataract surgery for the 1st time or those who were only familiar with ECCE.

CONCLUSION

This study revealed that both stepwise, supervised “start to finish” conventional and reverse methods of training phacoemulsification were safe and effective. However, the reverse method showed a nonsignificant trend toward lower PCR.

Financial support and sponsorship

Lions NAB Eye Hospital, Miraj, Maharashtra, India.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

Dr. Shailbala Patil, Director of Education and Training and Dr. Ashok Mahadik, Medical Director, Lions NAB Eye Hospital, Miraj, India. Mrs. Gogate, Statistician, Bharti Vidyapeeth Medical College, Sangli, India; Shrivallabh Sane, Data Clinic, Pune, India for statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chang DF. Tackling the greatest challenge in cataract surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:1073–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.068213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riaz Y, Mehta JS, Wormald R, Evans JR, Foster A, Ravilla T, et al. Surgical interventions for age-related cataract. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4:CD001323. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001323.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minassian DC, Rosen P, Dart JK, Reidy A, Desai P, Sidhu M, et al. Extracapsular cataract extraction compared with small incision surgery by phacoemulsification: A randomised trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:822–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.7.822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hennig A, Schroeder B, Kumar J. Learning phacoemulsification. Results of different teaching methods. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2004;52:233–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khanna RC, Kaza S, Palamaner Subash Shantha G, Sangwan VS. Comparative outcomes of manual small incision cataract surgery and phacoemulsification performed by ophthalmology trainees in a tertiary eye care hospital in India: A retrospective cohort design. BMJ Open 2012. 2012;2:pii: E001035. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quillen DA, Phipps SJ. Visual outcomes and incidence of vitreous loss for residents performing phacoemulsification without prior planned extra capsular cataract extraction experience. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:732–3. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)02150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rutar T, Porco TC, Naseri A. Risk factors for intraoperative complications in resident-performed phacoemulsification surgery. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:431–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Podbielski DW, Noble J, Gill HS, Sit M, Lam WC. A comparison of hand-and foot-activated surgical tools in simulated ophthalmic surgery. Can J Ophthalmol. 2012;47:414–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belyea DA, Brown SE, Rajjoub LZ. Influence of surgery simulator training on ophthalmology resident phacoemulsification performance. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37:1756–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2011.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briszi A, Prahs P, Hillenkamp J, Helbig H, Herrmann W. Complication rate and risk factors for intraoperative complications in resident-performed phacoemulsification surgery. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012;250:1315–20. doi: 10.1007/s00417-012-2003-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JS, Hou CH, Yang ML, Kuo JZ, Lin KK. A different approach to assess resident phacoemulsification learning curve: Analysis of both completion and complication rates. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:683–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6703103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Randleman JB, Wolfe JD, Woodward M, Lynn MJ, Cherwek DH, Srivastava SK. The resident surgeon phacoemulsification learning curve. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:1215–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.9.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas R, Naveen S, Jacob A, Braganza A. Visual outcome and complications of residents learning phacoemulsification. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1997;45:215–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischer AF, Pires EM, Klein F, Siqueira Bisneto O, Soriano ES, Moreira H. CBO/ALCON teaching method of phacoemulsification: Results of Hospital de Olhos do Paraná. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2010;73:517–20. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27492010000600010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haripriya A, Chang DF, Reena M, Shekhar M. Complication rates of phacoemulsification and manual small-incision cataract surgery at Aravind Eye Hospital. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38:1360–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dooley IJ, O’Brien PD. Subjective difficulty of each stage of phacoemulsification cataract surgery performed by basic surgical trainees. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32:604–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2006.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas R, Dogra M. An evaluation of medical college departments of ophthalmology in India and change following provision of modern instrumentation and training. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2008;56:9–16. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.37589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gogate P, Deshpande M, Dharmadhikari S. Which is the best method to learn ophthalmology. Resident doctors’ perspective of ophthalmology training? Indian J Ophthalmol. 2008;56:409–12. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.42419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gogate PM, Deshpande MD. The crisis in ophthalmology residency training programs. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2009;57:74–5. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.44504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grover AK. Postgraduate ophthalmic education in India: Are we on the right track? Indian J Ophthalmol. 2008;56:3–4. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.37581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]