Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

We hypothesized that pathologic ER stress contributes to beta cell death during development of type 1 diabetes. In this study, we investigated the occurrence of beta cell ER stress and the signaling pathways involved during discrete stages of autoimmune diabetes progression. The virus inducible BBDR rat model was utilized to systematically interrogate the three main ER stress signaling pathways (IRE1, PERK, and ATF6) in pancreatic beta cells during type 1 diabetes development.

Methods

ER stress and apoptotic markers were assessed by immunoblot analyses of isolated pancreatic islets and immunofluorescence staining of pancreas sections from control and virus induced rats. The time points analyzed were 1) early stages preceding insulitis and 2) a late stage during onset and progression of insulitis that precedes overt hyperglycemia.

Results

The IRE1 pathway, including its downstream component XBP-1, was specifically activated in pancreatic beta cells of virus induced rats at early stages prior to insulitis. Furthermore, ER stress-specific pro-apoptotic caspase 12, and effector caspase 3 were also activated at this stage. Activation of PERK and its downstream effector, pro-apoptotic CHOP, only occurred during late stages of diabetes induction concurrent with insulitis, whereas ATF6 activation in pancreatic beta cells was similar in control and virus induced rats.

Conclusions/interpretation

Activation of the IRE1 pathway and ER stress-specific pro-apoptotic caspase 12, prior to insulitis, are indicative of ER stress-mediated beta cell damage. The early occurrence of pathologic ER stress and death in pancreatic beta cells may contribute to the initiation and/or progression of virus induced autoimmune diabetes.

Keywords: apoptosis, BB rat, Seta cell, ER stress, IRE1 pathway, type 1 diabetes, virus

Introduction

Pancreatic beta cells have a highly developed endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in order to meet the heavy demand for insulin biosynthesis. Rapid changes in insulin requirements and/or deleterious alterations in the beta cells' environment may cause accumulation of misfolded proteins, and lead to a cellular adaptive response termed the unfolded protein response (UPR) [1]. Three ER transmembrane proteins are known to sense ER stress: IRE1 (inositol requiring protein-1), PERK (PKR-like ER kinase), and ATF6 (activating transcription factor 6). Each of these transducers activates separate, but integrated arms of the UPR to mitigate ER stress by decreasing protein translation, degrading misfolded proteins, and increasing the levels of ER-resident chaperones to aid in protein folding [2-4]. In conditions of unresolved ER stress, however, the UPR may initiate an ER stress-mediated apoptotic pathway [5]. Thus, the UPR may serve to underlie both physiologic and pathologic functions.

Unresolvable ER stress has been proposed to play a role in beta cell death during the progression of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes based on in vitro studies [6-9]. In support of this, pancreatic islets of type 2 diabetes patients are more susceptible to high glucose-induced ER stress than islets from non-diabetic controls [9] and, recently, increased levels of a few ER stress markers were found in islets from individuals with type 1 diabetes compared to non-diabetic controls [10]. A report in the NOD mouse, a well studied animal model of spontaneous autoimmune diabetes, demonstrates that beta cell ER stress occurs in 6-10 week old female mice, prior to diabetes onset [11]. However, because of the incomplete penetrance (∼70%) and variable time to insulitis and onset of hyperglycemia in this model, it is difficult to conclude whether beta cell ER stress contributes to, or is merely a consequence of, autoimmunity development. To elucidate this, we utilize the virus inducible BBDR rat which develops autoimmune diabetes at levels approaching 100% in ∼2 weeks following infection [12, 13]. Because the appearance of insulitis and subsequent development of hyperglycemia follow predictable kinetics, this rat model allows us to investigate ER stress signaling in pancreatic beta cells at discrete time points both prior to and during insulitis (lymphocytic infiltration of islets), the hallmark of autoimmunity.

Methods

Animals

BioBreeding Diabetes Resistant (BBDR) rats were bred at UMASS or obtained from BRM, Inc. (Worcester, MA, USA). Animals were housed in a viral-antibody-free facility and maintained in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, 1996) and guidelines of our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Diabetes induction

BBDR rats of either sex and 21-24 days old were injected i.p. with polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (pIC) (2 μg/g body weight) on three consecutive days (days -3, -2, and -1); pIC (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in Dulbecco's PBS. Rats received a single i.p. dose of 1 × 107 PFUs of Kilham rat virus (KRV) on day 0. Control rats received i.p. injections of PBS on the same days. Beginning at day 10 or 11 after KRV treatment, rats were tested for glycosuria (Clinistix, Bayer, Elkhart, IN, USA). Diabetes was confirmed by blood glucose concentration >14 mmol/l on two consecutive days (Accu-Chek Aviva, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

Islet isolation

In some experiments, pancreatic islets from BBDR rats were harvested by collagenase digestion as previously described [14]. Freshly isolated islets were snap frozen with liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80°C until use.

Immunoblot analysis

Rat islets were lysed with T-PER tissue protein extraction reagent (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) and protein concentrations were determined by bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Sigma-Aldrich). Protein samples were mixed with 4X SDS-PAGE loading buffer, and loaded onto 4-20% precast Tris-glycine gradient gels (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) along with ladder marker (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), and run at 150V for 1.5 hour. Gels were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes with iBlot (Invitrogen), blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 1 hour, and placed in primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Membranes were washed three times in tris buffered saline tween (TBST), and placed in secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 hour. Membranes were washed three times in TBST, developed with ECL (Gibco), and imaged using Kodak chemiluminescent film. Densitometric analyses were performed with Photoshop, all protein levels were normalized to actin levels and presented as average ± STDEV.

Immunofluorescence staining

Rat pancreas specimens were frozen in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. (Sakura Finetek USA, Inc., Torrance, CA, USA) with liquid nitrogen. Sections 5μ thick were cut with a cryostat (Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA), and stored at -80°C. Sections were fixed prior to staining with a mixture of ethanol and 0.1% of trichloroacetic acid for 15 minutes, then blocked with PBS-AT (500 ml PBS, 10 g BSA grade J, and 12.5 ml of 20% Triton X-100). Sections were incubated with primary and secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 hour separated by three washes in PBS. Mounting medium (Vectashield with DAPI, Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA) was added to the sections after three washes in PBS. Images were captured using spinning disk confocal microscopy on a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-E microscope, and analyzed using MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, Downington, PA, USA).

Antibodies

Antibodies for immunoblots included rabbit anti-human phosphospecific (Ser724) IRE-1α (Novus, Littleton, CO, USA); rabbit anti-human IRE-1α, rabbit anti-mouse caspase-12, and rabbit anti-mouse phospho-PERK (p-PERK, Thr980, 16F8) (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA); rabbit anti-human XBP-1, rabbit anti-PKR, rabbit anti-p-eIF2a (Ser51), and rabbit anti-human PERK (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA); mouse anti-human ATF6 (Imgenex, San Diego, CA, USA); rabbit anti-human caspase-3 (H-277), rabbit anti-mouse CHOP (F-168), and rabbit anti-insulin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). Mouse anti-actin (Chemicon International, Billerica, MA, USA) was used as a loading control. Secondary antibodies, anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG HRP conjugates were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

For immunofluorescence staining, in addition to the antibodies described above, frozen sections were stained with mouse anti-insulin (Sigma-Aldrich), guinea pig anti-insulin (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA), and chicken anti-insulin (Abcam). Secondary antibodies, Alexa Fluor 488 and 592 goat anti-mouse, anti-rabbit, anti-guinea pig, and anti-chicken were from Invitrogen. Isotype controls were from Pharmingen.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by Kaplan-Meier or unpaired t-test using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). A p value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Insulitis and diabetes onset in virus induced BBDR rats follow a predictable time course

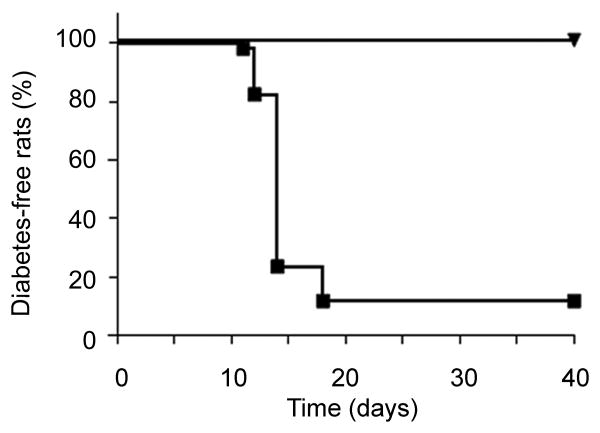

We have reported previously that the kinetics of type 1 diabetes development in the virus inducible BBDR rat model follows a consistent time course [12, 13]. To confirm this finding we treated BBDR rats with KRV+pIC or PBS control; as expected, most KRV+pIC treated rats progressed to diabetes by day 14 (Fig. 1). In addition, we assessed pancreatic islet morphology at selected time points following treatment. H&E staining of pancreas sections demonstrated that insulitis was first detectable at day 11 following KRV+pIC treatment, with more severe insulitis by day 14 (ESM Fig. 1a). Consistent with our H&E staining, islet-infiltrating CD3-positive T lymphocytes were first observed at day 11, with considerable infiltration by day 14 (ESM Fig. 1b). Based on these data and our earlier studies, we chose to investigate ER stress signaling pathways in pancreatic beta cells at discrete time points: day 4 and day 7 post-infection but prior to insulitis, and days 11-14 during the onset and progression of insulitis but prior to the development of overt hyperglycemia.

Fig. 1.

BBDR rats treated with KRV+pIC develop autoimmune type 1 diabetes with a predictable time course. BBDR rats were monitored for development of diabetes following KRV+pIC treatment; shown is a Kaplan-Meier plot for KRV+pIC compared with PBS treated rats, ***p<0.001.

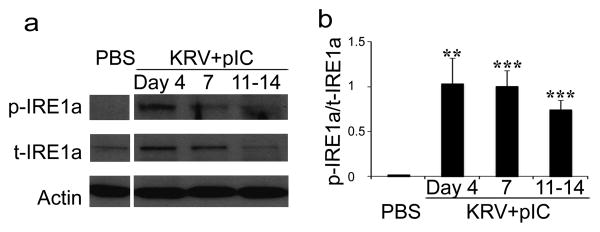

IRE1 phosphorylation and downstream activation of XBP-1 start at early, pre-insulitic stages and continue throughout diabetes development

To determine the occurrence of beta cell ER stress signaling during the development of virus induced type 1 diabetes, we first examined the IRE1 pathway. Immunoblot analysis showed that active (phosphorylated) IRE1 was undetectable in lysates of pancreatic islets isolated from PBS treated control rats, whereas IRE1 was highly active (phosphorylated) in islets isolated from rats at day 4 following KRV+pIC treatment, indicating upregulated IRE1 signaling (Fig. 2a). The ratio of phosphorylated to total IRE-1 in islets from KRV+pIC treated rats was maintained through day 7, as well as later insulitic stages (day 11-14) of diabetes development (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

IRE-1α phosphorylation occurs in early stage of diabetes induction. (a) Immunoblot of protein lysates of isolated pancreatic islets from PBS (control) or KRV+pIC treated rats for the phosphorylated form of IRE-1α (p-IRE-1α, Ser724) and total IRE-1α; actin was used as loading control. (b) Densitometric analysis (average ± STDEV, n=3) of p-IRE-1α/t-IRE-1α ratio; **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 compared with PBS (control) rats.

An important downstream component in the IRE1 pathway is XBP-1. Activated IRE1 has an endoribonuclease activity that generates a spliced, active form of XBP-1 that can translocate to the nucleus [15]. Expression of the active (spliced) form of XBP-1 was upregulated at day 4 post-infection and was sustained throughout diabetes induction, whereas the level in control rats was undetectable (Fig. 3a, b). Levels of the inactive (unspliced) form of XBP-1 were similar in both control and diabetes induced rats. To verify XBP-1 activation specifically in pancreatic beta cells, we stained pancreas sections from control and KRV+pIC treated rats for insulin and XBP-1. Pancreas sections from KRV+pIC treated rats showed distinct nuclear XBP-1 staining in insulin-positive beta cells throughout diabetes induction, consistent with XBP-1 activation, while the staining in PBS treated rats was negligible (Fig. 3c). Interestingly, alpha cells have recently been reported to undergo ER stress [16]; we also observed activated (nuclear) XBP-1 staining in glucagon-positive alpha cells of KRV+PIC treated rats (ESM Fig. 2).

Fig. 3.

Activation of XBP-1 occurs in early stage of diabetes induction. (a) Immunoblot of protein lysates of isolated pancreatic islets from PBS (control) or KRV+pIC treated rats for the spliced (s) and unspliced (u) forms of XBP-1; actin was used as loading control. (b) Densitometric analysis (average ± STDEV, n=3) of s-XBP-1/u-XBP-1 ratio; **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 compared with PBS (control) rats. (c) Immunofluorescence staining of frozen pancreas tissues; upper panels show staining with XBP-1 (red) and insulin (green), bottom panels show overlay with DAPI (blue) to visualize the nuclei. Arrows indicate beta cells positive for XBP-1 nuclear translocation. Representative immunofluorescence staining is shown; n=4 rats at each time point; at least 3 fields were examined for each rat. Magnification = 40x, scale bar = 20 μm.

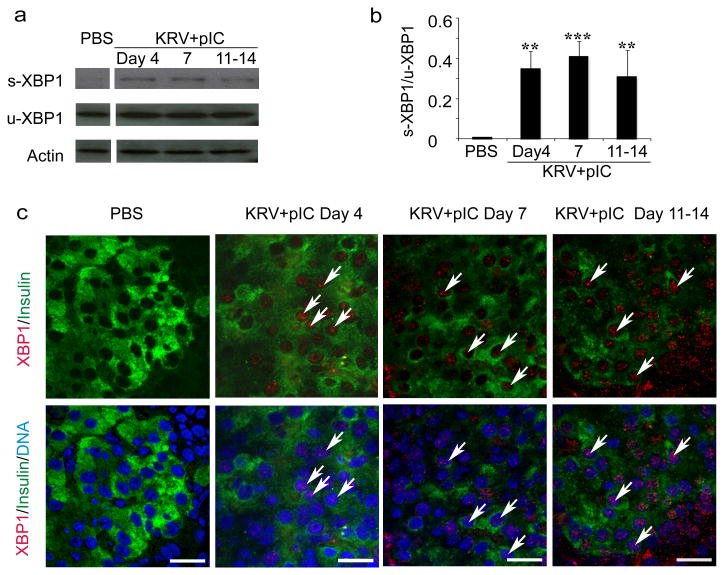

ER stress-specific caspase 12 activation occurs at early, pre-insulitic stages in pancreatic islets of KRV+pIC treated rats

Caspase 12 is an ER-localized pro-apoptotic protein that is activated specifically through the IRE1 signaling pathway in response to pathologic ER stress [17, 18]. We investigated whether upregulated IRE1 signaling in the islets of virus induced BBDR rats had transitioned to pathologic ER stress by measuring the expression of the activated (cleaved) form of pro-apoptotic caspase 12. Elevated levels of activated caspase 12 were found in isolated islets of KRV+pIC treated rats beginning at day 4, well prior to the onset of insulitis, as well as at day 7 and later, insulitic stages (day 11-14) of diabetes induction (Fig. 4a, b).

Fig. 4.

Activation of ER stress specific caspase 12 in pancreatic islets of diabetes induced BBDR rats occurs before the onset of insulitis. (a) Caspase 12 immunoblot of protein lysates of isolated pancreatic islets from PBS (control) or KRV+pIC treated rats; actin was used as loading control. (b) Densitometric analysis (average ± STDEV, n=3) of cleaved/uncleaved caspase 12 ratio; **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 compared with PBS (control) rats. (c) Immunofluorescence staining of frozen pancreas tissues; upper panels show staining for caspase 12 (red) and insulin (green), bottom panels show overlay with DAPI (blue) to visualize the nuclei. Arrows indicate beta cells with positive caspase 12 staining. Representative immunofluorescence staining is shown; n=4 rats at each time point; at least 3 fields were examined for each rat. Magnification = 40x, scale bar = 20 μm.

To determine caspase 12 expression specifically in beta cells, we co-stained pancreatic sections from control and KRV+pIC treated rats for insulin and caspase 12. Islets from PBS treated control rats showed robust insulin expression with very low or undetectable staining for caspase 12 (Fig. 4c). In contrast, by day 14 of virus infection, we observed that many islets consisted of beta cells with dramatically increased caspase 12 staining in conjunction with greatly reduced insulin levels.

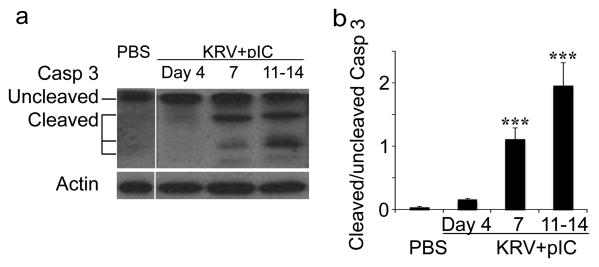

Activation of effector caspase 3 occurs prior to insulitis in pancreatic islets of KRV+pIC treated rats

We also examined the activation of caspase 3, the main effector caspase of apoptotic cell death, in pancreatic islets isolated from control and KRV+pIC treated rats. We observed a marked increase in the active (cleaved) form of caspase 3 at day 7 of KRV+pIC treatment, demonstrating that pancreatic islets undergo apoptosis prior to insulitis in this virus inducible diabetes model (Fig. 5). Caspase 3 activation was also high at late stages. In contrast, only the inactive (uncleaved) form of caspase 3 was observed in islets from PBS treated rats. To confirm apoptosis by a different method, we stained pancreas sections from control and treated rats for TUNEL. We found increased TUNEL-positive beta cells in the pancreas sections from KRV+pIC treated rats both prior to, and during, insulitis (ESM Fig. 3). Together with our caspase 12 results above, these data demonstrate that pro-apoptotic ER stress and pancreatic beta cell death first occur prior to the insulitic event, suggesting a role for pathologic ER stress in very early stages of virus induced diabetes.

Fig. 5.

Activation of caspase 3 in pancreatic islets of diabetes-induced BBDR rats occurs before the onset of insulitis. (a) Caspase 3 immunoblot of protein lysates of isolated pancreatic islets from PBS (control) or KRV+pIC treated rats; actin was used as loading control. (b) Densitometric analysis (average ± STDEV, n=3) of cleaved/uncleaved caspase 3 ratio; ***p<0.001 compared with PBS (control) rats.

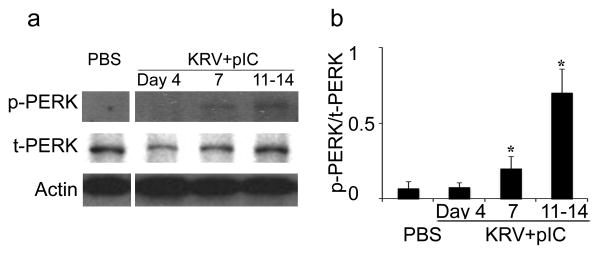

PERK phosphorylation and the pro-apoptotic ER stress marker, CHOP, are highly increased in pancreatic islets only at the late, insulitic stage of diabetes induction

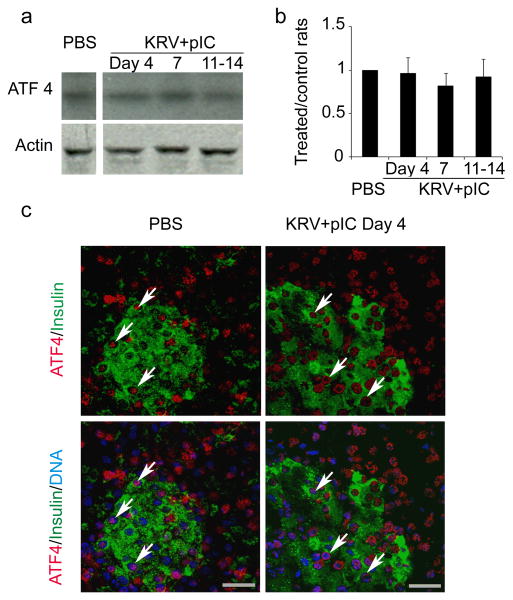

We next interrogated the PERK pathway and found that PERK was present in islet lysates from both control and treated rats at similar levels. The active (phosphorylated) form of PERK was moderately increased at day 7, but the highest levels of activation were seen at days 11-14 when lymphocytic infiltration was occurring (Fig. 6). In addition we analyzed our islet protein lysates for ATF4, a downstream transcription factor in the PERK pathway [19], but we observed little difference in ATF4 expression in islets from control or KRV+pIC treated rats (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

PERK pathway activation in pancreatic islets occurs mainly at late stages of diabetes induction. (a) Immunoblot of protein lysates of isolated pancreatic islets from PBS (control) or KRV+pIC treated rats for the phosphorylated (p) active form of PERK (p-PERK, Thr980) and total (t) PERK; actin was used as loading control. (b) Densitometric analysis (average ± STDEV, n=3) of p-PERK/t-PERK ratio; *p<0.05 compared with PBS (control) rats.

Fig. 7.

Expression of ATF4 is not significantly affected during induction of diabetes. (a) ATF4 immunoblot of protein lysates of isolated pancreatic islets from PBS (control) or KRV+pIC treated rats; actin was used as loading control. (b) Densitometric analysis (average ± STDEV, n=3) of ATF4. (c) Immunofluorescence staining of frozen pancreas tissues; upper panels show staining with ATF4 (red) and insulin (green), bottom panels show overlay with DAPI (blue) to visualize the nuclei. Representative immunofluorescence staining is shown; n=4 rats at each time point, at least 3 fields were examined for each rat. Magnification = 40x, scale bar = 30 μm.

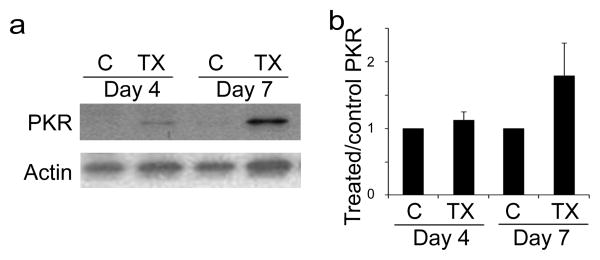

Activated PERK inhibits cellular mRNA translation by directly phosphorylating the eukaryotic translation initiation factor, eIF2α [4]; eIF2α can also be phosphorylated by PKR, which is activated by double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) such as synthetic pIC [20, 21]. Similar to phosphorylated PERK, we found increased expression of PKR in islets of KRV+pIC treated rats at day 7 (Fig. 8). We next analyzed our islet protein lysates for eIF2α phosphorylation. However, immunoblot analysis of both control and KRV+pIC treated rat islets showed relatively similar levels of eIF2α phosphorylation (Fig. 9). Together with our ATF4 results, these data suggest that pancreatic islets normally exhibit high physiologic UPR activity.

Fig. 8.

Expression of PKR is increased in KRV+pIC treated rats. a) PKR immunoblot of protein lysates of isolated pancreatic islets from PBS control (C) or KRV+pIC treated (TX) rats; actin was used as loading control. (b) Densitometric analysis (average ± STDEV, n=3) of treated/control ratio of PKR (normalized to actin).

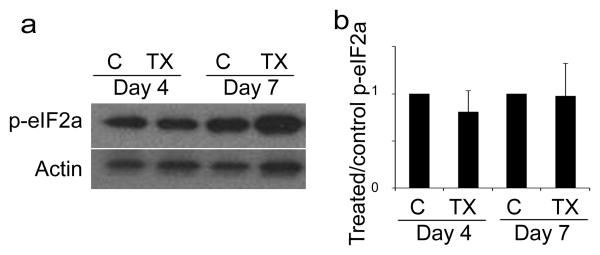

Fig. 9.

Expression of phosphorylated eIF2α is similar in control and KRV+pIC treated rats. a) Phosphorylated eIF2α(p-eIF2a) immunoblot of protein lysates of isolated pancreatic islets from PBS control (C) or KRV+pIC treated (TX) rats; actin was used as loading control. (b) Densitometric analysis (average ± STDEV, n=3) of treated/control ratio of p-eIF2a (normalized to actin).

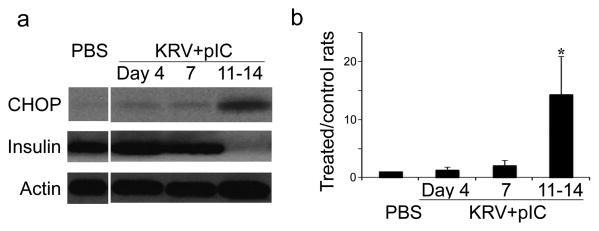

Lastly, we measured the expression of CHOP (CCAAT/-enhancer-binding-protein homologous protein), which is regulated by the PERK pathway and acts to induce apoptosis during prolonged ER stress [3, 19, 22, 23]. Immunoblot analysis of isolated islets revealed that CHOP expression was highly elevated only at the late stage during autoreactive T lymphocyte infiltration (Fig. 10a, b). Concomitant with high levels of CHOP expression, we found marked reductions in the level of intracellular insulin (Fig. 10a), consistent with significant beta cell dysfunction or death at this stage.

Fig. 10.

Pro-apoptotic CHOP expression in pancreatic islets occurs mainly at late stages of diabetes induction. Pancreatic tissues from BBDR rats treated with KRV+pIC or PBS (control) were recovered at the time points indicated. (a) Immunoblot of protein lysates of isolated pancreatic islets from PBS (control) or KRV+pIC treated rats for CHOP and insulin; actin was used as loading control. (b) Densitometric analysis (average ± STDEV, n=3) of CHOP; *p<0.05 compared with PBS (control) rats.

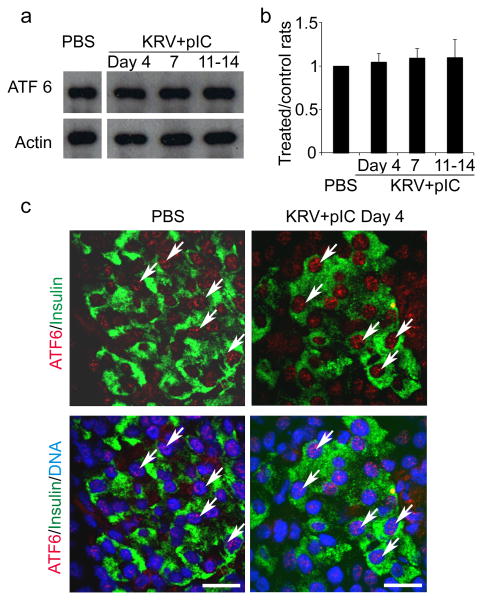

Expression and activation of ATF6 is not significantly affected by diabetes induction

Finally, we examined the third major ER stress transducer, ATF6. Upon ER stress, ATF6 translocates from the ER to the Golgi where it is cleaved and travels to the nucleus to activate transcription of downstream ER stress target genes [24, 25]. Immunoblot analysis of pancreatic islets isolated from control and KRV+pIC treated rats showed high levels of ATF6 in both groups (Fig. 11a, b); nuclear translocation of ATF6 in beta cells was also similar in control and treated rats (Fig. 11c). These data demonstrate that although pancreatic beta cells express robust levels of ATF6, presumably a reflection of their high insulin load, the expression levels and activation (nuclear translocation) of ATF6 were not significantly altered with diabetes induction.

Fig. 11.

High basal expression of ATF6 is not affected by diabetes induction. (a) ATF6 immunoblot of protein lysates of isolated pancreatic islets from PBS (control) or KRV+pIC treated rats; actin was used as loading control. (b) Densitometric analysis (average ± STDEV, n=3) of ATF6. (c) Immunofluorescence staining of frozen pancreas tissues; upper panels show staining for ATF6 (red) and insulin (green), bottom panels show overlay with DAPI (blue) to visualize the nuclei. Arrows indicate beta cells with positive ATF6 nuclear translocation. Representative immunofluorescence staining is shown; n=4 rats at each time point, at least 3 fields were examined for each rat. Magnification = 40x, scale bar = 20 μm.

Discussion

In this study we utilized the KRV+pIC inducible BBDR rat model to investigate a role for pancreatic beta cell ER stress during the development of virus induced type 1 diabetes. We systematically analyzed the three major ER stress pathways and focused on early stages in diabetes development (days 4 and 7), prior to histological- and immuno-detectable insulitis, and a late stage (days 11-14), corresponding to the onset and progression of insulitis, but prior to diabetes. Here we report specific activation of the IRE1 pathway and its downstream component XBP-1 at early, pre-insulitic stages of diabetes development. Importantly, we found that pro-apoptotic caspase 12, a downstream effector of pathologic IRE1 signaling, was also activated during this stage. These data demonstrate that pathologic ER stress contributes to early stage beta cell death well prior to the infiltration of autoreactive lymphocytes in this virus induced model of type 1 diabetes.

Of note, viral infections have long been implicated as important factors in the etiology and/or pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes in HLA-susceptible individuals [26-28]; further, polymorphisms in the IFIH1 gene have been convincingly associated with type 1 diabetes [11, 29]. The IFIH1 gene encodes for the interferon-induced helicase C domain-containing protein-1 that detects double-stranded RNA produced by certain viruses and mediates an antiviral response [30]. In the genetically susceptible BBDR rat the mechanism underlying the development of autoimmune diabetes following exposure to KRV infection remains incompletely understood. KRV infects lymphoid tissue, but does not directly infect pancreatic islets [31, 32]; co-treatment with pIC, a synthetic double-stranded RNA, greatly increases the incidence of diabetes [12, 33]. In the BBDR rat, KRV+pIC treatment causes a potent innate immune response mediated by TLR9 and TLR3, respectively, and results in a rapid upregulation of multiple proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines [34-36].

In our study specific in vivo activation of IRE1, and its downstream effector XBP-1, occurred at early stages of diabetes induction when beta cells were exposed to these multiple proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. This is consistent with earlier reports that in vitro exposure of beta cells to cytokines leads to the induction of ER stress [37, 38]. We also found increased levels of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), indicative of oxidative stress, in islet lysates from rats at days 4 and 7 of KRV+pIC treatment (data not shown). Prolonged exposure of the pancreatic islets of KRV+pIC treated rats to these cytotoxic insults may underlie the transition to pathologic ER stress and beta cell apoptosis [17], as we also observed activation of pro-apoptotic caspase 12 specifically in beta cells during this early stage of diabetes induction. Indeed, although the human ortholog of caspase 12 is non-functional due to deleterious mutations in its open reading frame [39], in rodents caspase 12 belongs to the sub-group of inflammatory caspases [40, 41]; importantly, capsase 12 is the sole caspase localized to the ER, and it is activated specifically through the IRE1 signaling pathway [17, 18].

Caspase 12, in turn, is involved in the apoptotic cascade that activates the downstream effector, caspase 3 [42, 43]. In our study caspase 3 was activated at early stages of diabetes induction and, although we cannot rule out that other apoptotic pathways may also be involved in caspase 3 activation, our data suggest that pathologic IRE1 signaling likely plays a contributory role in this early beta cell death. In support of this, we and others have recently reported that thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) is a possible link between pathologic ER stress, especially via the IRE1 pathway, and inflammasome activation and IL-1β production, which in turn promotes beta cell apoptosis [44, 45]. Indeed, consistent with these reports, IL-1β expression was detected in isolated islets of BBDR rats prior to insulitis (day 7 of KRV+pIC treatment, data not shown). In an earlier report, we also found that exposure of beta cells to chronic hyperglycemia in vitro caused IRE1 activation and an accompanying decrease in insulin production [46]. Yet the initial activation of IRE1 in our current study was not a consequence of hyperglycemia, as treated rats maintained normal blood glucose levels during this early stage of diabetes progression.

During the late insulitic stage of diabetes induction, activated caspase 12 remained elevated along with a dramatic induction of the pro-apoptotic protein CHOP. CHOP deletion has been shown to promote beta cell survival in multiple mouse models of diabetes, consistent with its pro-apoptotic function [23, 47, 48]. CHOP induction in our rat model primarily occurred only at late stages of diabetes induction, when lymphocytic infiltration was robust. Consistent with this, Tersey et al [11] recently reported that ER stress responsive genes, including CHOP and active (spliced) XBP-1, were upregulated in the pancreatic islets of NOD mice during the insulitic stage, but prior to diabetes onset; this correlated with the decreased insulin production and relative glucose intolerance of the NOD compared to diabetes resistant mouse strains. Interestingly, expression levels of CHOP were also increased in islets from individuals with type 1 diabetes compared to non-diabetic controls, although there was no difference observed in XBP-1 levels [10]. Together, these data demonstrate that multiple ER stress pathways contribute to pancreatic islet destruction during infiltration of autoreactive lymphocytes.

In summary, we utilized the virus inducible BBDR rat model to investigate in vivo ER stress signaling in pancreatic beta cells during development of autoimmune type 1 diabetes. Following diabetes induction, the IRE1 pathway and caspase 12 were specifically activated at early time points well prior to insulitis. Our data support a scenario in which pathologic IRE1-mediated ER stress signaling and activation of pro-apoptotic molecules contributes to early pancreatic beta cell damage which may, in turn, release beta cell autoantigens that elicit or exacerbate the autoreactive immune attack that ultimately mediates complete β-cell destruction [49]. This report highlights the IRE1 ER stress pathway as a unique target in the early initiation and progression of virus induced type 1 diabetes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Aldo A. Rossini from Joslin Diabetes Center, Boston, USA, for helpful discussions and insights. We also thank Elaine Norowski and Linda Leehy (Program in Molecular Medicine) for their outstanding technical assistance and Dr. Paul Furcinitti (Digital Light Microscopy Core Facility) at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, USA, for assistance with spinning disk confocal microscopy.

Funding: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI046629, the Beta Cell Biology Consortium DK72473, and grants from the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation, International, the Helmsley Foundation and the Brehm Foundation. Core resources supported by the NIH Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center grant (DK32520) were used.

The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Abbreviations

- ATF6

factivating transcription factor 6

- BBDR

BioBreeding Diabetes Resistant

- CHOP

CCAAT/-enhancer-binding-protein homologous protein

- eIF2α

eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- IRE1

inositol requiring protein-1

- KRV

Kilham rat virus

- PERK

PKR-like ER kinase

- pIC

polyinosinic: polycytidylic acid

- PKR

double stranded RNA dependent protein kinase

- UPR

unfolded protein response

- XBP-1

X-box binding protein-1

Footnotes

Author contribution: CY designed and performed research, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. Pd and AJ performed research and revised and reviewed the manuscript, BO-M and FU contributed to design of research and revised and reviewed the manuscript, and RB designed research, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript.

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

References

- 1.Wu J, Kaufman RJ. From acute ER stress to physiological roles of the Unfolded Protein Response. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:374–384. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertolotti A, Zhang Y, Hendershot LM, Harding HP, Ron D. Dynamic interaction of BiP and ER stress transducers in the unfolded-protein response. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:326–332. doi: 10.1038/35014014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schroder M, Kaufman RJ. ER stress and the unfolded protein response. Mutat Res. 2005;569:29–63. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo D, He Y, Zhang H, et al. AIP1 is critical in transducing IRE1-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress response. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11905–11912. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710557200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Araki E, Oyadomari S, Mori M. Impact of endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway on pancreatic beta-cells and diabetes mellitus. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2003;228:1213–1217. doi: 10.1177/153537020322801018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oslowski CM, Urano F. The binary switch between life and death of endoplasmic reticulum-stressed beta cells. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2010;17:107–112. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3283372843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eizirik DL, Cardozo AK, Cnop M. The role for endoplasmic reticulum stress in diabetes mellitus. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:42–61. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marchetti P, Bugliani M, Lupi R, et al. The endoplasmic reticulum in pancreatic beta cells of type 2 diabetes patients. Diabetologia. 2007;50:2486–2494. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0816-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marhfour I, Lopez XM, Lefkaditis D, et al. Expression of endoplasmic reticulum stress markers in the islets of patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2417–2420. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2604-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tersey SA, Nishiki Y, Templin AT, et al. Islet beta-cell endoplasmic reticulum stress precedes the onset of type 1 diabetes in the nonobese diabetic mouse model. Diabetes. 2012;61:818–827. doi: 10.2337/db11-1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mordes JP, Bortell R, Blankenhorn EP, Rossini AA, Greiner DL. Rat models of type 1 diabetes: genetics, environment, and autoimmunity. ILAR J. 2004;45:278–291. doi: 10.1093/ilar.45.3.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kruger AJ, Yang C, Lipson KL, et al. Leptin treatment confers clinical benefit at multiple stages of virally induced type 1 diabetes in BB rats. Autoimmunity. 2011;44:137–148. doi: 10.3109/08916934.2010.482116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottlieb PA, Berrios JP, Mariani G, et al. Autoimmune destruction of islets transplanted into RT6-depleted diabetes-resistant BB/Wor rats. Diabetes. 1990;39:643–645. doi: 10.2337/diab.39.5.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshida H, Oku M, Suzuki M, Mori K. pXBP1(U) encoded in XBP1 pre-mRNA negatively regulates unfolded protein response activator pXBP1(S) in mammalian ER stress response. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:565–575. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akiyama M, Liew CW, Lu S, et al. X-Box Binding Protein 1 Is Essential for Insulin Regulation of Pancreatic alpha-Cell Function. Diabetes. 2013;62:2439–2449. doi: 10.2337/db12-1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szegezdi E, Fitzgerald U, Samali A. Caspase-12 and ER-stress-mediated apoptosis: the story so far. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1010:186–194. doi: 10.1196/annals.1299.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakagawa T, Zhu H, Morishima N, et al. Caspase-12 mediates endoplasmic-reticulum-specific apoptosis and cytotoxicity by amyloid-beta. Nature. 2000;403:98–103. doi: 10.1038/47513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harding HP, Novoa I, Zhang Y, et al. Regulated translation initiation controls stress-induced gene expression in mammalian cells. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1099–1108. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hotamisligil GS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the inflammatory basis of metabolic disease. Cell. 2010;140:900–917. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakamura T, Furuhashi M, Li P, et al. Double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase links pathogen sensing with stress and metabolic homeostasis. Cell. 2010;140:338–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang XZ, Lawson B, Brewer JW, et al. Signals from the stressed endoplasmic reticulum induce C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP/GADD153) Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4273–4280. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oyadomari S, Takeda K, Takiguchi M, et al. Nitric oxide-induced apoptosis in pancreatic beta cells is mediated by the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10845–10850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191207498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haze K, Yoshida H, Yanagi H, Yura T, Mori K. Mammalian transcription factor ATF6 is synthesized as a transmembrane protein and activated by proteolysis in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3787–3799. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas SE, Dalton LE, Daly ML, Malzer E, Marciniak SJ. Diabetes as a disease of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2010;26:611–621. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akerblom HK, Vaarala O, Hyoty H, Ilonen J, Knip M. Environmental factors in the etiology of type 1 diabetes. Am J Med Genet. 2002;115:18–29. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nairn C, Galbraith DN, Taylor KW, Clements GB. Enterovirus variants in the serum of children at the onset of Type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 1999;16:509–513. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.1999.00098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.von Herrath MG, Holz A, Homann D, Oldstone MB. Role of viruses in type I diabetes. Semin Immunol. 1998;10:87–100. doi: 10.1006/smim.1997.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nejentsev S, Walker N, Riches D, Egholm M, Todd JA. Rare variants of IFIH1, a gene implicated in antiviral responses, protect against type 1 diabetes. Science. 2009;324:387–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1167728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chistiakov DA. Interferon induced with helicase C domain 1 (IFIH1) and virus-induced autoimmunity: a review. Viral Immunol. 2010;23:3–15. doi: 10.1089/vim.2009.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown DW, Welsh RM, Like AA. Infection of peripancreatic lymph nodes but not islets precedes Kilham rat virus-induced diabetes in BB/Wor rats. J Virol. 1993;67:5873–5878. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.5873-5878.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zipris D. Epidemiology of type 1 diabetes and what animal models teach us about the role of viruses in disease mechanisms. Clin Immunol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mordes JP, Bortell R, Doukas J, et al. The BB/Wor rat and the balance hypothesis of autoimmunity. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1996;12:103–109. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0895(199607)12:2<103::AID-DMR161>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zipris D, Lien E, Nair A, et al. TLR9-signaling pathways are involved in Kilham rat virus-induced autoimmune diabetes in the biobreeding diabetes-resistant rat. J Immunol. 2007;178:693–701. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zipris D, Lien E, Xie JX, Greiner DL, Mordes JP, Rossini AA. TLR activation synergizes with Kilham rat virus infection to induce diabetes in BBDR rats. J Immunol. 2005;174:131–142. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zipris D. Innate immunity in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2011;27:824–829. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chambers KT, Unverferth JA, Weber SM, Wek RC, Urano F, Corbett JA. The role of nitric oxide and the unfolded protein response in cytokine-induced beta-cell death. Diabetes. 2008;57:124–132. doi: 10.2337/db07-0944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cardozo AK, Ortis F, Storling J, et al. Cytokines downregulate the sarcoendoplasmic reticulum pump Ca2+ ATPase 2b and deplete endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+, leading to induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes. 2005;54:452–461. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.2.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fischer H, Koenig U, Eckhart L, Tschachler E. Human caspase 12 has acquired deleterious mutations. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;293:722–726. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00289-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nadiri A, Wolinski MK, Saleh M. The inflammatory caspases: key players in the host response to pathogenic invasion and sepsis. J Immunol. 2006;177:4239–4245. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scott AM, Saleh M. The inflammatory caspases: guardians against infections and sepsis. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:23–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hitomi J, Katayama T, Taniguchi M, Honda A, Imaizumi K, Tohyama M. Apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress depends on activation of caspase-3 via caspase-12. Neurosci Lett. 2004;357:127–130. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kerbiriou M, Teng L, Benz N, Trouve P, Ferec C. The calpain, caspase 12, caspase 3 cascade leading to apoptosis is altered in F508del-CFTR expressing cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oslowski CM, Hara T, O'Sullivan-Murphy B, et al. Thioredoxin-interacting protein mediates ER stress-induced beta cell death through initiation of the inflammasome. Cell Metab. 2012;16:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lerner AG, Upton JP, Praveen PV, et al. IRE1alpha induces thioredoxin-interacting protein to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and promote programmed cell death under irremediable ER stress. Cell Metab. 2012;16:250–264. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lipson KL, Fonseca SG, Ishigaki S, et al. Regulation of insulin biosynthesis in pancreatic beta cells by an endoplasmic reticulum-resident protein kinase IRE1. Cell Metab. 2006;4:245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song B, Scheuner D, Ron D, Pennathur S, Kaufman RJ. Chop deletion reduces oxidative stress, improves beta cell function, and promotes cell survival in multiple mouse models of diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3378–3389. doi: 10.1172/JCI34587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oyadomari S, Mori M. Roles of CHOP/GADD153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:381–389. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Horwitz MS, Ilic A, Fine C, Rodriguez E, Sarvetnick N. Presented antigen from damaged pancreatic beta cells activates autoreactive T cells in virus-mediated autoimmune diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:79–87. doi: 10.1172/JCI11198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]