Abstract

Female-initiated methods of HIV prevention are needed to address barriers to HIV prevention rooted in gender inequalities. Understanding the socio-cultural context of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) trials, including gender-based violence, is thus critical. MTN-003C (VOICE-C), a qualitative sub-study of the larger MTN-003 (VOICE) trial, examined socio-cultural barriers and facilitators to PrEP amongst women in Johannesburg. We conducted focus group discussions, in-depth interviews, and ethnographic interviews with 102 trial participants, 22 male partners, 17 community advisory board members, and 23 community stakeholders. We analysed how discussions of rape are emblematic of the gendered context in which HIV risk occurs. Rape emerged spontaneously in half of discussions with community advisory board members, two-thirds with stakeholders and among one-fifth of interviews/discussions with trial participants. Rape was used to reframe HIV risk as external to women’s or partner’s behaviour and to justify the importance of PrEP. Our research illustrates how women, in contexts of high levels of sexual violence, may use existing gender inequalities to negotiate PrEP use. This suggests that future interventions should simultaneously address harmful gender attitudes, as well as equip women with alternative means to negotiate product use, in order to more effectively empower women to protect themselves from HIV.

Keywords: gender, sexual violence, HIV prevention, female-initiated methods, Pre-exposure prophylaxis, South Africa

Introduction

In 2012, an estimated 35.3 million people were living with HIV worldwide with women bearing the brunt of the epidemic. In low and middle-income countries, and in sub-Saharan Africa in particular, women account for over half (57%) of the population living with HIV (UNAIDS 2013). Policymakers and researchers have consistently attributed women’s increased HIV burden to experiences of gender inequalities, including gender-based violence (Garcia-Moreno et al. 2013; The Global Fund 2008; UNAIDS 2013; Jewkes et al. 2010; Campbell et al. 2008; Dunkle et al. 2004; Maman et al. 2000). The pathway between these issues, however, is complex, in part because of the various forms gender-based violence takes and the multiple levels within a society in which inequalities occur. Sexual violence, in particular rape, committed both by known and unknown perpetrators, is perhaps the most obvious link to HIV risk. However, psychological and other forms of physical violence can increase risk by reducing women’s ability to protect themselves (e.g. to negotiate condom use) and more broadly control their sexual experiences (UN Trust Fund 2012; Kacanek et al. 2013). Ingrained social, economic and political gender inequalities, or ‘structural violence,’ also contribute to women’s heightened HIV vulnerability (Farmer 2004). Fewer economic and educational opportunities for women intensify dependency on men and lead to increases in transactional sex (Hunter 2007; Fox et al. 2007; Wingood and DiClemente 2000; Heise and Elias 1995). Gender norms that legitimise male sexual infidelity contribute to women’s inability to negotiate safer sex, including male condom use (WHO 2009; Fox et al. 2007; Wingood and DiClemente 2000).

In direct response to the identified need for alternatives to male-initiated HIV prevention methods, prevention trials have sought to evaluate various pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) formulations, such as vaginal gels, oral tablets, and most recently, vaginal rings that can be female-initiated and theoretically female-controlled. Described as technologies intended to empower women (Bell 2000), these formulations are designed to overcome at least some of the gendered barriers to protection, described above. While several of these trials have reported on the intersection between trial participation, product use, and participants’ gender roles, they typically examine these issues in the context of intimate partnerships (Stadler et al. 2014; Kacanek et al. 2013; Montgomery et al. 2008, 2011). Within these findings, structural gender inequalities are often highlighted as shaping women’s lives and potentially influencing product use. For instance one recent publication, which reported on the experience of intimate partner violence among participants in the Microbicide Development Program trial, revealed high levels of everyday violence against women. The authors conclude that this pervasive fear and experience of violence, while not directly related to trial participation or product use, raises important questions about the ability of female-initiated HIV prevention methods to successfully empower women within the existing gender status-quo (Stadler et al. 2014).

Drawing on qualitative data from VOICE-C, an ancillary study of the multisite Vaginal and Oral Interventions to Control the Epidemic (VOICE, MTN-003) phase IIB clinical trial evaluating daily oral and vaginal PrEP, this paper aims to explore the broader context of gender-based violence through participants’ discussions of rape. We examine how this collective narrative reflects on the context of gender inequality and the intersections between this context and product use during women’s participation in the trial.

Methods

Research Setting and Study Participants

Details about the research setting, data collection methods and procedures, as well as primary results for VOICE-C, have been previously published (van der Straten et al. 2014). Briefly, VOICE-C was a qualitative exploratory ancillary study conducted concurrently to the VOICE trial, a multi-country HIV prevention clinical trial evaluating daily oral and vaginal PrEP (Marrazzo et al. 2015). VOICE-C was conducted at a single clinical site at the Wits Reproductive Health Institute (Wits RHI), in Johannesburg, South Africa. Wits RHI is located in Hillbrow, a low-income densely populated inner-city suburb of Johannesburg, in which a diverse population of South Africans and migrant populations reside. Guided by a socio-ecological framework, the study included a range of participant groups and methods to explore factors influencing participants’ experience and use of study products operating at the community, organisational, and household-levels. The four participant groups included: female participants (N=102), male partners (N=22), community advisory board members (N=17), and community stakeholders (N=23). To reach these sample sizes, 144 female participants, 55 male partners, 20 community advisory board members, and 46 community stakeholders were screened for participation. Female participants were recruited from randomly pre-selected VOICE participants, male partners were recruited from VOICE participants who had provided permission for their partners to be contacted, community advisory board members were recruited from the existing local board, and community stakeholders were identified and recruited via study staff. Participants came from Hillbrow, other neighborhoods, as well as more distant townships in Gauteng Province such as Orange Farm and Soweto.

Data Collection

Data collection took place over a period of approximately two years – from July 2010 to August 2012. Female participants were randomly pre-selected and pre-assigned to one of three interview modalities, chosen to provide complimentary data. In-depth interviews provided information on individual level experiences, serial ethnographic interviews captured participant’s life context and allowed for observation of change over time, and exit focus group discussions collected data on group norms. Male partners were assigned to either in-depth interviews or focus group discussions and members of the community advisory board and key community stakeholders participated exclusively in focus group discussions. Community advisory board members were individuals selected by the leadership of Wits RHI to perform an advisory and community liaison function for the research institution. Community stakeholders were selected to represent individuals who lived or worked in Hillbrow and each focus group discussion represented a homogeneous group in terms of their professional affiliation: (1) community-based organisations involved in HIV prevention and response; (2) local media, including community newspapers and radio stations; and (3) a local neighborhood improvement programme, which included police officers, youth representatives, and victim support counsellors. Interviews covered a range of topics from broader questions about the community context to specific experiences with product use. Gender inequality and violence was not included as an explicit topic area for questioning; however, it came up through discussions of community context, interpersonal relationships, as well as around product use. All participant groups completed a brief demographic survey upon enrolment.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards at RTI International, and the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Witwatersrand, and overseen by the regulatory infrastructure of the NIH Microbicide Trials Network. All reports of potential social harms, including reported experience of violence, were investigated by the site Investigator of Record, recorded in participant files, and participants were either provided or referred to appropriate care and counselling. Social harms were defined as any harm reported by participants during their study participation that was related to participation or procedures.

Data Analysis

Demographic data were tabulated using SAS (version 9.3, Cary, NC). All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and translated into English. Every transcript was reviewed twice for quality control, first by researchers at the Wits RHI in South Africa then by the US-based data centre (RTI/WGHI). All transcribed interviews were coded in Nvivo (version 9.0, Burlington, MA) by the analysis team. An initial codebook was iteratively developed and refined upon review and subsequent coding of transcripts. An acceptable level of inter-coder reliability was set at ≥ 80% coding agreement. Throughout the analysis process, approximately 10% of the transcripts were double coded by two or more team members in order to monitor and maintain a high-level of inter-coder reliability.

For this analysis, text coded as “violence” – defined as “anything about violence or violent behaviors (actual experiences or discussion of potential risk) in relation to anyone (i.e. participant, partner, family, community members, etc.)” – from all transcripts was systematically reviewed. Upon review of these coded segments, the relative importance of rape emerged as an area requiring further inquiry given its regular, yet unsolicited occurrence across study groups. Additionally, a key word search for “rape” and “sexual violence” was conducted across all transcripts to ensure that all mentions of this topic were captured. Once all qualitative data regarding participants’ discussions of rape were identified, we employed a phenomenological approach to understand how the ‘phenomenon’ of rape broadly provided insight into participant perceptions of their lived experiences in their community, and into women’s trial experiences, more specifically. This process included a review of the content on rape and a summarisation of content by identified theme.

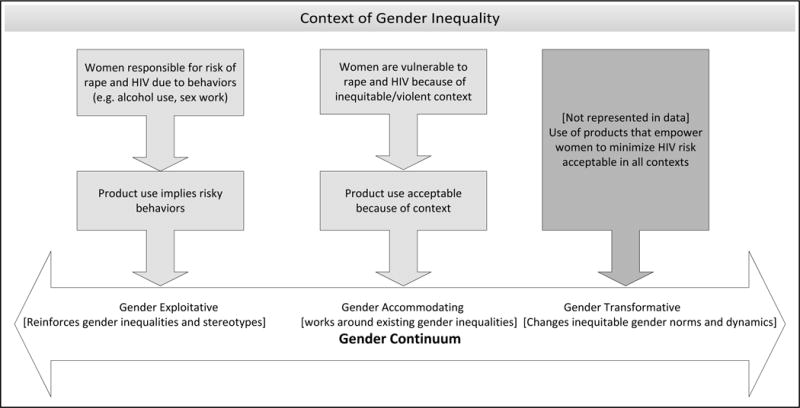

As the meanings related to gender norms and roles emerged, we used the gender integration continuum as an organising framework (Kraft et al. 2014) to understand how these meanings compared to PrEP’s goal of empowering women to prevent HIV. The continuum, a tool typically used by gender practitioners and programme planners to plan or assess how well an intervention is currently identifying, examining, and attending to gender considerations, was developed based on a range of approaches to addressing gender, drawing heavily on the field of HIV prevention and response. This framework categorises approaches into those that are either exploitative, accommodating, or transformative (defined in Figure 1). An exploitative approach, for example, might be one that utilises a harmful norm such as the portrayal of men as sexually aggressive to encourage male condom use. On the other hand, a transformative approach might seek to challenge norms that suggest women who use condoms are promiscuous. Given oral and vaginal PrEP’s aim and portrayal as technologies designed to overcome gendered barriers to female HIV prevention, the three gender aware categories provided a structure for understanding how participant discussions of rape reflected the positioning of female-initiated PrEP within the existing gendered context. Participant quotations are used throughout the manuscript to demonstrate the identified themes. Redundant or non-illustrative text in the quotations presented was removed by the authors and is indicated by ellipses: “…”. Local terms, jargon or nonspecific text have been replaced or clarified by the authors in square brackets. All associated names are pseudonyms.

Figure 1. Advancing the case for PrEP along the gender continuum.

Represented in light grey, themes found in participant discussions of rape are displayed according to where along the gender integration continuum they fall. The dark grey box represents the idealised hope for PrEP, as described by the PrEP research community.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Characteristics of the 164 participants are presented in Table 1. Among female participants (N=102), the majority had completed secondary school or more, was married or had a primary partner and earned an income. Nevertheless, 80% received financial or material support from their partners. Only about a quarter of female participants and male partners considered their current residence as “home,” reflecting a transient population (see table 1). A comparison of female participants mentioning rape with those who did not revealed no significant differences (comparison not presented).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants by VOICE-C study group

| VOICE Female Participants (N=102) | Male Partners (N=22) | Community Advisory Board Members (N=17) | Community Stakeholders (N=23) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (median, IQR, min-max) | 26.8 (26, 7, 19–40) | 31.4 (30, 10, 22–45) | 38.5 (39, 31, 20–60) | 38.5 (39, 17, 22–53) |

| Completed secondary school or more | 69(68%) | 14(64%) | 10(59%) | 21(91%) |

| Earns an income | 58(57%) | 18(82%) | 6(35%) | 21(91%) |

| Current residence is “home” | 30(29%) | 5(23%) | 12(71%) | 13(57%) |

| Married or has a primary partner | 100(98%) | 22(100%) | 6(35%)1 | 11(48%)1 |

| Living with primary partner | 44(45%) | 16(73%) | ||

| Partner provides financial/material support | 81(80%) | |||

| Type of interviews received | ||||

| In-depth interview | 41 (40%) | 14 (64%) | ||

| Ethnographic Interviews2 | 21 (21%) | |||

| Focus Group Discussions3** | 40 (39%) | 8 (36%) | 17 (100%) | 23 (100%) |

Community advisory board members and community stakeholders were only asked if they were married, thus this does not represent the number who may have also had a primary partner.

Participants randomised to ethnographic interviews completed 2–4 interviews over the course of VOICE-C.

All study participants took part in one focus group discussion except for community advisory board members who participated in up to 3 focus group discussions over the course of VOICE-C.

Overview of Participant Discussions of Rape

Among participants, the issue of rape was spontaneously mentioned in half of the focus group discussions with community advisory board members, two-thirds of focus group discussions with community stakeholders and among one fifth of in-depth interviews/ethnographic interviews/focus group discussions with female participants, two of whom described personal experiences of being raped. Notably, while a handful of male partners discussed issues related to violence, such as high levels of community violence or their own perpetration of physical intimate partner violence, they were the only participant group that did not specifically mention rape. Community advisory board and community stakeholder discussions focused on the broader community context that contribute to women’s risk of rape, the relationship between rape and HIV risk, and community responses to this issue. The remainder of the paper presents results based on the sub-set of participants mentioning rape.

Two broad themes emerged from the data on rape, which are used to frame the results. First, rape was used as an expression of women’s overall vulnerability to HIV. Second, rape legitimised the use of female-initiated technologies of HIV prevention. Within each of these themes, discussions pertaining to rape highlighted how these participants internalised existing harmful gender norms or accommodated these norms as a means to allow for use of products otherwise seen as challenging existing gender norms. Results are presented by theme; however, Figure 1 provides an overview of where these themes fall on the gender continuum, displaying how participants’ accounts reflected both internalisation (“gender exploitative”) and a contextualised view (“gender accommodating”) of the gendered experience, as opposed to the hope of the PrEP research community for female-initiated methods that would transform norms through women’s empowerment (“gender transformative”).

Rape as a Reflection of Women’s Vulnerability

Setting the stage for the gendered context in which women may use or need PrEP, participants who described vulnerability to rape and HIV, spoke of it in terms of individual behaviour (e.g., women’s own actions such as drinking alcohol or engaging in risky sex) as well as a result of larger social-economic issues (e.g., employment and housing insecurity).

Illustrating the view that women’s behaviour contribute to personal accountability for rape, a few participants described the need for women to take responsibility for their own safety including safety from rape. In these instances, the implication was that women who put themselves in situations or settings that involve alcohol and multiple sexual partners, contexts thought to be socially unacceptable for women, are knowingly placing themselves at risk of being raped and acquiring HIV.

“I: How rough is Soweto and what is happening in Soweto?

R: Soweto is rough; I mean that one should not go out at night. Having many boyfriends. Things like that.

I: So, what happens if a person goes out at night and do those things?

R: You put yourself at risk obviously.

I: What risks, please explain to me?

R: The risk could be that a woman is raped and also contracts the diseases [e.g. HIV].” [Anashe, Female IDI participant]

These themes permeated Dikeladi’s description of her personal experience of being raped. She described leaving a bar early where she was with friends and being raped on the way home. Counter-acting an internalised social belief linking alcohol and drinking venues to personal responsibility for rape, she justified her lack of responsibility by noting that she wasn’t drinking. She also described how the man who raped her initially assumed that she was a sex worker. She said,

“He was saying that I must sleep with him and he would give me money. [He said that] I must tell him how much money he must give me. I said I won’t do such a thing. I told him that even my man doesn’t treat me like that, hey!” [Dikeledi, Female EI participant]

Dikeledi subsequently described this man’s role in raping an elderly woman, who presumably had no individual responsibility for being raped, further deflecting any potential judgment that her individual behaviours may incite blame.

Unlike descriptions of personal culpability, participants also described their life context as violent and risky for all women. These participants reflected on the connections between structural issues of gender-inequality, such as women’s economic insecurity with their experience or threat of sexual violence. For instance, Patience, a community member who works with victims of rape, depicted her community as one where many women are exposed to sexual violence and are infected with HIV as a result. She highlighted the role of women’s economic dependency as a backdrop to their vulnerability to rape:

“You find that she was raped by her brother or uncle for years. At the end of the day you get one or two children opening up saying that ‘you know I was afraid to talk about this [that she was raped] because he is paying rent for me and buying household groceries.’” [Patience, Community Stakeholder FGD participant].

Several individuals also highlighted the link between the physical environment and women’s vulnerability to rape, describing open and vacant areas as places of risk. For example Mmakgomo said “where I walk there is a vacant area and you find that people tell me that in that vacant area there are people who stay there who rape and rob you see.” [Mmakgomo, Female IDI participant]

Structural vulnerabilities such as limited employment opportunities and weak community networks, especially for recent migrants who struggled to find social networks of support, were also associated with women’s vulnerability to rape. These vulnerabilities contributed to threats of sexual violence against themselves and their family members. For example, Khauhelo, a female migrant from KwaZulu-Natal who lived alone with her young female child, described her fear that her landlord would rape her child while she’s away for work in the evenings.

“Another thing I don’t like about the place I live in currently is that the landlord is naughty. He is going to rape my child one day and that scares me too much because I work night shifts.” [Khauhelo, Female IDI participant]

Rape as a Rationale for Female-Initiated HIV Prevention

Another important and related theme that emerged was the justification of the use of female-initiated HIV prevention methods, such as oral or vaginal PrEP, as protection in the case of rape. These discussions, however, highlighted a spectrum of gendered perspectives, ranging from those accepting the idea that use of an HIV prevention product may only be suitable for “high-risk” women engaging in individual-level sexual risk behaviours (e.g. selling sex, having multiple partners) to those who acknowledged that these products could increase women’s protection in the event of being raped.

Representing the view that these products filled a unique gap in the prevention of HIV in cases of rape, Lynn said:

“But at times, there are some people that get raped after they first get kidnapped, so even if there is a way or window period when the clinic could do something about it when you get raped … for some reason I’ve got this belief that this tablet, if I was to be in such circumstances, it might give me immunity so that I don’t get infected by HIV until I manage to get help.” [Lynn, Female EI participant]

Reinforcing the view that only promiscuous women are at risk of rape and are in need of HIV prevention, Ratu described how VOICE study products were intended specifically for women who drink in local taverns. When asked to explain why she initially made that association, she said:

“Because it would help them. They get raped most of the times and they also sleep with men without using condoms. I don’t know what the gel does… I think it works the same as the condom. So, we told ourselves that it will help them like that.” [Ratu, Female IDI participant]

Other accounts demonstrate how this inferred sexual promiscuity associated with using female-initiated HIV prevention created suspicion among male partners. As Lily, an FGD participant explained, not only does it imply mistrust, but also heightens men’s scrutiny of their female partners’ behaviour and can even result in women’s reduced individual freedom. In regards to her own partner, she reported that “he would tell me that I’m taking the tablets because I went and cheated on him.” Contrasting women’s vulnerability to HIV through rape with the challenge of negotiating product use in a relationship when use implies promiscuity, she later went on to say:

“You know if it can happen that this tablet can protect us as women then it can be a good thing and it can also be a bad thing, I can say that it can be a good thing to us as women and it can be a bad thing to the men because the tablet would be focusing on protecting us more than them and that would result in them always looking at us and watching us and that can result in a lot of divorces as well…Sometimes you can think about this disease only and think that you are protected from it and then get raped in the process, so there are many things that we go through as women. So it’s entirely up to you, how you will treat yourself; you know since some of us don’t have husbands then it can be painful to have a husband that will always be watching your every move.” [Lily, Female FGD participant]

Given that using HIV prevention products implied promiscuity and sexual deviance, participants referred to their risk of rape to legitimise use of the study products. For example:

“There are rapists now and you don’t know what you will come across, when you don’t have a condom or anything in your bag. I know that people can consider me to be a whore but I am just preparing myself for any accident that I might come across, because sometimes if you can hear stories of people who have HIV another one will tell you that they have been raped and that means she has felt the pain twice, the pain of being raped and that of contracting HIV, she could also get pregnant during that process and that only adds to the pain she feels. So now how many pains does she now have?” [Precious, Female EI participant]

Beyond justifying one’s own motivation to use the study products, there was evidence that some participants used the risk of rape to explain their study participation to other individuals in their lives, including friends and partners. Mmakgomo, who described prior experience in an abusive relationship, explained how her own vulnerability to rape helped her partner understand her product use. She told him: “You see because you never know when you go around what will happen on the way; you find that you get raped, neh. As I am taking these tablets they are going to protect me from that thing.” [Mmakgomo, Female IDI participant]

According to participants, these interpretations of PrEP were also prompted at times by study staff. One participant asked the staff nurse to explain why women needed to protect themselves using condoms and the study products, the nurse reportedly said: “The reason why we advise you to prevent it’s because you can meet someone and that person might rape you, so that won’t prevent you from getting sick and being pregnant unless you are using something to protect yourself with.” [Jess, Female EI participant]

Discussion

Echoing sentiments reported in exploratory research on the acceptability of microbicides (van der Straten et al. 2012; Orner et al. 2006; Becker et al. 2004), the topic of rape was spontaneously brought up in our interviews and focus group discussions within the VOICE-C qualitative study. Although the literature on PrEP has briefly noted rape as a potential rationale for product use, this paper explores discussions of rape in greater depth. Participant discussions of rape provide insight into the complexities behind this notion as participants highlighted several ways in which women perceive and explain the role of PrEP in their lives. These included protecting them against sexual violence victimisation, and assuaging social and male partner criticisms of women’s sexuality. Underlying these discussions of rape, remains the challenge of using female-initiated HIV prevention methods in a context of unequal gender norms.

Although they represented a minority of participants overall, these accounts highlighted the sense that women are vulnerable to rape. They also illustrate social norms and moral categories of acceptable and unacceptable sexual conduct. Internalised by some participants, ‘gender exploitative’ views were expressed through the association between HIV prevention method use with women who behave improperly (i.e. drink and have multiple sexual partners). Devoid of a gendered understanding of the social vulnerabilities placing women at risk for rape and HIV, these discussions stigmatised women by portraying them as promiscuous and exposing themselves to risk of rape and therefore HIV. By contrast, other participants attempted to refute the notion that paired ‘sexually risky women’ as prime candidates for these HIV prevention products. These reports reflected discourse previously documented in microbicide acceptability research regarding how female-initiated HIV prevention products threaten traditional gender structures and fears that they could encourage social problems such as increases in women’s promiscuity (Montgomery et al. 2008; Bentley et al. 2004). More dominant in the data was the ‘gender accommodating’ view, when participants’ descriptions or experiences of gendered inequalities shifted the blame for HIV vulnerability from individual women to a broader social context of anonymous sexual violence. In doing so, they rationalised the need to increase women’s sexual agency in order to protect themselves against HIV in a way that did not implicate them as behaving improperly or immorally. Finally, the ‘gender transformative’ view that the products empower women to prevent HIV was not present this discourse; however as suggested later, future research that systematically explores how the products may be perceived as empowering by women is needed.

Rape not only serves to legitimise female-initiated methods in a society that portrays women at risk for HIV as sexually promiscuous, but also helps to negotiate product use with male partners who may otherwise feel threatened by the insinuation of infidelity on their or their partner’s part (Parker et al. 2014; MacPhail et al. 2009; Langen 2007). Again, microbicide acceptability research has often documented concerns that product use may demonstrate a lack of trust in committed sexual relationships (Montgomery et al. 2008; Orner et al. 2006; Bentley et al. 2004). Indeed, while male participants did not suggest rape was a rationale for their partner’s product use, VOICE-C findings published elsewhere highlight male partners’ concerns about trust and female promiscuity in relation to female initiated methods of HIV prevention (Montgomery et al. 2014). As such, what’s described as the widespread threat of rape could become a reassuring rationale for HIV prevention product use in the context of a committed relationship. Invoking rape may have deferred having to discuss the risk of HIV due to partner infidelity. Related to the unacceptability of condom use in committed relationships (Montgomery et al. 2008; Maharaj and Cleland 2004; Karim Abdool et al. 1992), women’s attempts to differentiate PrEP from condoms as protection against rape perhaps mitigated the potential loss of trust.

Invoking rape as a tactic for mitigating social barriers to HIV prevention methods by no means negates the real insecurity that women face. Despite decreasing levels of reported violence in the VOICE-C recruitment areas (Crime Stats 2013), women in South Africa are extremely vulnerable to sexual violence, documented in a growing literature on this topic (Jewkes et al. 2009, 2011; Wood 2005; Jewkes and Abrahams 2002; Kalichman and Simbayi 2004). Moreover, although participants’ discussions of rape mainly focused on perpetration of rape by strangers, this may obfuscate partner’s sexual violence. For instance, a survey conducted among antenatal clinic attendees in Soweto found that 55% of women experienced physical or sexual violence at the hands of their partner (Dunkle et al. 2004). A cross-sectional survey conducted among 1737 South African men found that 27.6% of men reported committing rape against an intimate partner, stranger, or acquaintance (Jewkes et al. 2011). In this context of gender based violence, it is perhaps unsurprising that rape became a spontaneous focus of discussions about biomedical technologies designed to empower women and protect themselves against HIV.

Notwithstanding these insights, this study has several limitations. Firstly, the qualitative research conducted was exploratory. Study participants represent only a fraction of the participants in the larger VOICE trial and are representative only of the participants at the Wits RHI site in Johannesburg, South Africa (van der Straten et al. 2014). In addition, as women’s gendered experiences with using PrEP were not explored systematically, these findings represent only what arose spontaneously among a subset of the participants. Although the authors feel confident that these results represent an important finding, future research should include more direct exploration of how PrEP might have increased sexual health autonomy and empowerment. While participants reported that the threat of rape was used as a rationale to motivate product use by trial staff, we were unable to ask staff to corroborate, as this was not part of our research protocol. We did, however, confirm that none of the study materials included content on the use of PrEP in the context of rape or sexual violence. The men who presented for in-depth interviews and focus group discussions were a selective group who may be in more supportive, stable relationships and more open to the idea of female-initiated HIV prevention, than partners from women who did not provide permission to contact. Thus, the lack of discussion of rape among male partners may reflect our sample more so than the absence of this idea among men. However, the saliency of rape and sexual violence in discussions about PrEP for women is strengthened by the relatively large sample size utilised in the VOICE-C study compared to other qualitative studies, combined with the multiple participant groups and forms of qualitative data collection utilised (i.e. in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, ethnographic interviews).

While recognising the limitations of what can be addressed during a clinical trial, understanding participants’ discussions of rape still holds several practical implications for future female-initiated HIV prevention trials. For one, these results suggest the importance of carefully attending to messages presented to and/or understood by participants, staff, and the wider community about HIV prevention technologies. Although the threat of rape to legitimise PrEP was not included in VOICE trial educational messages, concerns about female sexual violence can recast PrEP as a technology to protect women against HIV infections due to rape. This may alleviate tensions within partnerships about trust. However, there is a danger that by framing PrEP primarily as protecting against HIV transmitted through rape, this may undermine its broader use in preventing HIV exposure through consensual sexual contacts; and it may limit the perceived need of PrEP among people who do not feel at risk of rape. Finally, it reinforces negative gender norms by suggesting that the main legitimate reason women should protect themselves from HIV is because of their exposure to sexual violence from a stranger. This demonstrates a need for a more comprehensive initiative that recognises and challenges existing harmful gender social norms, including the idea that rape is a rationale for women’s PrEP use. Indeed, this is in-line with existing recommendations calling for HIV prevention to challenge gender norms that accommodate male sexual violence (Dunkle and Jewkes 2007). This may include community sensitisation, staff training, as well as participant counseling designed to give women other ways to safely negotiate product use with partners (MacPhail et al. 2009). Attempts to counteract these notions will also require working with men to shift norms around partner communication and sexual decision-making (Parker et al. 2014; Langen 2007). Incorporating additional measures of gender equality, such as partner communication and joint sexual decision-making, can help monitor the positive impact of female-initiated HIV products on women’s empowerment and evaluate whether intervention strategies are in fact gender transformative.

Acknowledgments

We would like to pay tribute to the women and men who participated in this study, their dedication and commitment made this study possible. The contributions of the MTN Behavioral Research Working Group, the VOICE trial leadership, Katie Schwartz and Katherine Richards of FHI 360, Helen Cheng at RTI International, Sello Seoka at Wits RHI and other Protocol study team members are acknowledged as critical in the development, implementation, and/or analysis of this study. We would also like to thank Deborah Baron for her review of a previous version of the manuscript. The full MTN003-C study team can be viewed at http://www.mtnstopshiv.org/studies/1087

This study was supported through the Microbicide Trials Network (MTN) which is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (UM1AI068633, UM1AI106707), with co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Mental Health, all components of the US National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. JS was supported in part by UKaid from the Department for International Development through the STRIVE Research Programme Consortium (Ref: Po 5244). However, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the department’s official policies. Finally, the development of this paper was funded in part by RTI International.

References

- Becker J, Dabash R, McGrory E, Copper D, Harries J, Hoffman M, Moodley J, Orner P, Bracken H. Paving the Path: Preparing for Microbicide Introduction Report of a Qualitative Study in South Africa. New York: EngenderHealth; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bell Susan E. Empowering technologies: connecting women and science in microbicide research. Sciences Sociales et Sante. 2000;18(2):121–142. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley ME, Fullem AM, Tolley EE, Kelly CW, Jogelkar N, Srirak N, Mwafulirwa L, Khumalo-Sakutukwa G, Celentano DD. Acceptability of a microbicide among women and their partners in a 4-country phase I trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(7):1159. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC, Baty ML, Ghandour RM, Stockman JK, Francisco L, Wagman J. The intersection of intimate partner violence against women and HIV/AIDS: a review. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion. 2008;15(4):221–231. doi: 10.1080/17457300802423224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crime Stats. Crime Stats South Africa. 2013 Accessed July 28. http://www.crimestatssa.com/index.php.

- Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, Gray GE, McIntryre JA, Harlow SD. Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. The Lancet. 2004;363(9419):1415–1421. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle KL, Jewkes R. Effective HIV prevention requires gender-transformative work with men. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2007;83(3):173–174. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.024950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer P. An anthropology of structural violence (Sidney Mintz Lecture) Current Anthropology. 2004;45:305–317. [Google Scholar]

- Fox AM, Jackson SS, Hansen NB, Gasa N, Crewe M, Sikkema KJ. In Their Own Voices: A Qualitative Study of Women’s Risk for Intimate Partner Violence and HIV in South Africa. Violence Against Women. 2007;13(6):583–602. doi: 10.1177/1077801207299209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Moreno C, Pallitto C, Devries K, Stockl H, Watts C, Abrahams N. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Heise LL, Elias C. Transforming AIDS prevention to meet women’s needs: a focus on developing countries. Social Science & Medicine. 1995;40(7):931–943. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00165-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter M. The changing political economy of sex in South Africa: The significance of unemployment and inequalities to the scale of the AIDS pandemic. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64:689–700. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Abrahams N. The epidemiology of rape and sexual coercion in South Africa: an overview. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55(7):1231–1244. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Jewkes R, Sikweyiya Y, Morrell R, Dunkle K. Understanding men’s health and use of violence: interface of rape and HIV in South Africa. Cell. 2009;82(442):3655. [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Shai N. Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: a cohort study. The Lancet. 2010;376(9734):41–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60548-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Sikweyiya Y, Morrell R, Dunkle K. Gender inequitable masculinity and sexual entitlement in rape perpetration South Africa: findings of a cross-sectional study. PloS one. 2011;6(12):e29590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kacanek D, Bostrom A, Montgomery ET, Ramjee G, de Bruyn G, Blanchard K, Rock A, Mtetwa S, van der Straten A, MIRA Team Intimate Partner Violence and Condom and Diaphragm Non-Adherence among Women in an HIV Prevention Trial in Southern Africa. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2013 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a6b0be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC. Sexual assualt history and risks for sexually transmitted infections among women in an African township in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2004;16(6):681–689. doi: 10.1080/09540120410331269530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim Abdool SS, Karim Abdool Q, Preston-Whyte E, Sankar N. Reasons for lack of condom use among high school students. South African medical journal= Suid-Afrikaanse tydskrif vir geneeskunde. 1992;82(2):107–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft JM, Gwinn Wilkins K, Morales GJ, Widyono M, Middlestat SE. An Evidence Review of Gender-Integrated Interventions in Reproductive and Maternal-Child Health. Journal of Health Communication: International Perspectives. 2014;19(sup1):122–141. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2014.918216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langen TT. Gender Power Imbalance on Women’s Capacity to Negotiate Self-protection Against HIV/AIDS in Botswana and South Africa. African Health Sciences. 2007;5(3):188–197. doi: 10.5555/afhs.2005.5.3.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maharaj P, Cleland J. Condom Use Within Marital and Cohabiting Partnerships in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Studies in Family Planning. 2004;35(2):116–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2004.00013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maman S, Campbell J, Sweat M, Gielen AC. The intersections of HIV and violence: directions for future research and interventions. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;50(4):459–478. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrazzo J, Ramjee G, Richardson B, Gomez K, Mgodi N, Nair G, Palanee T, et al. Tenofovir-based pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(6):509–518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPhail C, Terris-Prestholt F, Kumaranayake L, Ngoako P, Watts C, Rees H. Managing men: women’s dilemmas about overt and covert use of barrier methods for HIV prevention. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2009;11(5):485–497. doi: 10.1080/13691050902803537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery CM, Lees S, Stadler J, Morar NS, Ssali A, Mwanza B, Mntambo M, Phillip J, Watts C, Pool R. The role of partnership dynamics in determining the acceptability of condoms and microbicides. AIDS Care. 2008;20(6):733–740. doi: 10.1080/09540120701693974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery ET, van der Straten A, Chidanyika A, Chipato T, Jaffar S, Padian N. The importance of male partner involvement for women’s acceptability and adherence to female-initiated HIV prevention methods in Zimbabwe. AIDS & Behavior. 2011;15(5):959–969. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9806-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery ET, van der Straten A, Stadler J, Hartmann M, Magazi B, Mathebula F, Laborde N, Soto-Torres L. Male partner influence on women’s HIV prevention trial participation and use of pre-exposure prophylaxis: the importance of “understanding. AIDS & Behavior. 2014;19(5):784–793. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0950-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orner P, Harries J, Cooper D, Moodley J, Hoffman M, Becker J, McGrory E, Dabash R, Bracken H. Challenges to microbicide introduction in South Africa. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63(4):968–978. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker L, Pettifor A, Sibeko J, MacPhail C. Concerns about partner infidelity are a barrier to adoption of HIV-prevention strategies among young South African couples. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2014;16:7, 792–805. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.905707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadler J, Delany-Moretlwe S, Palanee T, Rees H. Hidden harms: Women’s narratives of intimate partner violence in a microbicide trial, South Africa. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;110:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Global Fund. Global Fund Gender Equality Strategy. Geneva: Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. Global Report: UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2013. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- UN Trust Fund. Effective Approaches to Addressing the Intersection of Violence Against Women and HIV/AIDS: Findings from Programmes Supported by the UN Trust Fund to End Violence Against Women. Geneva: UN Trust Fund to End Violence Against Women; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- van der Straten A, Montgomery ET, Cheng H, Wegner L, Masenga G, von Mollendorf C, Bekker L, Ganesh S, Young K, Romano J. High acceptability of a vaginal ring intended as a microbicide delivery method for HIV prevention in African women. AIDS & Behavior. 2012;16(7):1775–1786. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Straten A, Stadler J, Hartmann M, Mathebula F, Laborde N, Soto-Torres L. Women’s experiences with oral and vaginal pre-exposure prophylaxis: the VOICE-C qualitative study in Johannesburg, South Africa. PloS one. 2014;9(2):e89118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Integrating gender into HIV/AIDS programmes in the health sector: tool to improve responsiveness to women’s needs. Geneva: WHO; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV-related exposures, risk factors, and effective interventions for women. Health Education & Behavior. 2000;27(5):539–565. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood K. Contextualizing group rape in post-apartheid South Africa. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2005;7(4):303–317. doi: 10.1080/13691050500100724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]