Abstract

Purpose

To describe official adult-onset offenders, investigate their antisocial histories and test hypotheses about their origins.

Methods

We defined adult-onset offenders among 931 Dunedin Study members followed to age 38, using criminal-court conviction records.

Results

Official adult-onset offenders were 14% of men, and 32% of convicted men, but accounted for only 15% of convictions. As anticipated by developmental theories emphasizing early-life influences on crime, adult-onset offenders’ histories of antisocial behavior spanned back to childhood. Relative to juvenile-offenders, during adolescence they had fewer delinquent peers and were more socially inhibited, which may have protected them from conviction. As anticipated by theories emphasizing the importance of situational influences on offending, adult-onset offenders, relative to non-offenders, during adulthood more often had schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and alcohol-dependence, had weaker social bonds, anticipated fewer informal sanctions, and self-reported more offenses. Contrary to some expectations, adult-onset offenders did not have high IQ or high socioeconomic-status families protecting them from juvenile conviction.

Conclusions

A tailored theory for adult-onset offenders is unwarranted because few people begin crime de novo as adults. Official adult-onset offenders fall on a continuum of crime and its correlates, between official non-offenders and official juvenile-onset offenders. Existing theories can accommodate adult-onset offenders.

Keywords: adult-onset offending, theory, life-course criminology, longitudinal, Dunedin

It seems counterintuitive that someone who successfully navigated the volatile adolescent period crime-free would suddenly start engaging in crime as an adult. Yet, according to official data, adult-onset offending exists. Adult-onset offenders, as reported by most studies, represent a substantial portion of ever-convicted individuals (although the size of this adult-onset group is uncertain because of methodological heterogeneity among studies, see Table 1). According to projections of lifetime conviction risk, at least one-quarter of first-time convictions will occur after 30 years of age, well into adulthood (Skardhamar, 2014). Ample cautionary evidence, however, shows that individuals’ age of onset of criminal behavior is overestimated by official data (Elander, Rutter, Simonoff, & Pickles, 2000; Farrington, 1989; Farrington, Jolliffe, Loeber, & Homish, 2007; Kazemian & Farrington, 2005; McGee & Farrington, 2010; Moffitt, Caspi, Rutter, & Silva, 2001; Sohoni, Paternoster, McGloin, & Bachman, 2014; Theobald & Farrington, 2011). As a result, an initial official crime record during adulthood cannot necessarily be interpreted as evidence that the offender began criminal activity as an adult.

Table 1.

Evidence of adult-onset offending, sources from 1998 to 2014. Updated table of Eggleston & Laub (2002)1

| Study name/description | Data source | Analytic sample | Followed to age: |

Type of crime data | Adult offenders | Juvenile-onset adult offenders |

Adult-onset adult offenders |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % of sample |

n | % of adult offenders |

n | % of adult offenders |

|||||

| Prospective studies appearing in Eggleston & Laub (2002) | ||||||||||

| St. Louis Municipal Psychiatric Clinic Study |

Robins (1966) | 441 males and females in St. Louse, antisocial referrals and nondelinquent controls |

43 | Nontraffic arrests | 233 | 53% | 218 | 94% | 15 | 6% |

| Glueck Study | Glueck & Glueck (1968) | 880 males in Boston, one half delinquent |

31 | Arrests for nontraffic offenses |

328 | 37% | 266 | 81% | 62 | 19% |

| Cambridge-Somerville Study |

McCord (1978) | 506 males in Massachusetts |

mid to late 40s |

Serious convictions | 91 | 18% | 50 | 55% | 41 | 45% |

| Marion County Youth Study |

Polk et al. (1981) | 1,227 males in the 10th grade in 1964 in Marion County, OR |

30 | Police and court records for minor and serious offending |

90 | 7.3% | 35 | 29% | 55 | 61% |

| Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development |

Farrington (1983) | 395 males in London |

25 | Nonminor convictions |

107 | 27% | 55 | 51% | 52 | 49% |

| Langan & Farrington (1983) | 395 males in London |

25 | Burglary or violence convictions |

55 | 14% | 19 | 35% | 36 | 65% | |

| Swedish Project Metropolitan |

Janson (1983) | 7,710 males in Stockholm, Sweden |

26 | Crimes known to police, including nonminor traffic |

1,639 | 21% | 601 | 37% | 1,038 | 63% |

| Kratzer & Hodgins (1999) | 13,852 males and females in Stockholm, Sweden |

30 | All criminal convictions, including nonminor traffic |

1,945 | 14% | 800 | 41% | 1,145 | 59% | |

| Racine Cohort Studies | Shannon (1988) | 633 males and females born in 1942 in Wisconsin |

32 | Nontraffic police contacts |

242 | 38% | 118 | 49% | 124 | 51% |

| Shannon (1988) | 1,297 males and females born in 1949 in Wisconsin |

25 | Nontraffic police contacts |

472 | 36% | 305 | 65% | 167 | 35% | |

| Shannon (1998) | 1,357 males and females born in 1955 in Wisconsin |

32 | Nontraffic police contacts |

458 | 34% | 236 | 51% | 222 | 29% | |

| 1945 Philadelphia Birth Cohort Follow-up Study |

Wolfgang et al. (1987) | 975 males in Philadelphia born in 1945 |

30 | Police contacts for nontraffic offenses |

290 | 30% | 176 | 61% | 114 | 39% |

| Individual Development and Environment |

Magnusson (1988) | 1,389 males and females in Orebro, Sweden |

30 | Nonminor arrests | 248 | 18% | 99 | 14% | 149 | 86% |

| Montreal Study | LeBlanc and Frechette (1989) | 1,602 males in Montreal |

25 | Convictions for indictable crimes |

172 | 11% | 25 | 14% | 149 | 86% |

| LeBlanc and Frechette (1989) | 470 male wards of the court in Montreal |

25 | Convictions for indictable crimes |

339 | 72% | 288 | 85% | 51 | 15% | |

| LeBlanc and Frechette (1989) | 196 male wards of the court in Montreal |

25 | Self-report offending |

177 | 90% | 150 | 85% | 27 | 15% | |

| Kauai Study | Werner & Smith (1992) | 505 males and females in Kauai, HI |

32 | Nontraffic police records and court convictions |

31 | 6% | 21 | 68% | 10 | 32% |

| 1958 Philadelphia Birth Cohort |

Tracy & Kempf-Leonard (1996) | 27,160 males and females in Philadelphia born in 1958 |

26 | Police contacts for nontraffic offenses |

3,617 | 13% | 2,041 | 56% | 1,576 | 44% |

| Prospective studies published from 1999 forward, not included in Eggleston & Laub (2002) | ||||||||||

| Racine data | Eggleston & Laub (2002) | 732 males and females in Racine, WI born 1942 or 1949 |

25 and 32 |

Police contact for nontraffic offenses |

179 | 24% | 96 | 54% | 83 | 46% |

| Youth Court Survey and Adult Criminal Court Survey |

Carrington, Matarazzo, & deSouza (2005) | 323,694 Canadian males and females born 1979–1980 |

22 | Court referrals and convictions |

37,426 | 12% | 12,044 | 32% | 25,382 | 68% |

| Philadelphia portion of National Collaborative Perinatal Project |

Gomez-Smith & Piquero (2005) | 987 African American males and females born 1959–1962 |

36–39 | Convictions and police contacts |

154 | 16% | 76 | 49% | 78 | 51% |

| Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry of the Central Institute of Mental Health, Mannheim |

Lay et al. (2005) | 321 German males and females born in 1970 |

25 | Official convictions, self-reports, and interviews with parents |

72 | 22% | 27 | 38% | 45 | 63% |

| Jyväskylä Longitudinal Study of Personality and Social Development |

Pulkkinen, Lyyra, & Kokko (2009) | 196 Finnish males born in 1959 |

47 | Official convictions, police-registered crime, and self- reports |

89 | 45% | 57 | 64% | 32 | 36% |

| Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development |

McGee & Farrington (2010) | 404 British males born in 1953 for which a criminal records search was conducted at 48 years of age |

50 | Official convictions | 1672 | 41% | 129 | 77% | 38 | 23% |

| Sohoni et al. (2014) | 411 British males born in 1953 |

50 | Official convictions, adulthood at 25 years of age |

1672 | 43% | 138 | 83% | 29 | 17% | |

| National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), Waves 1–3 |

Mata & van Dulmen (2012) | 5,579 males and females 13–18 years of age at Wave 1, with complete antisocial behavior data |

18–25 | Self-reported antisocial behavior |

9–13% (est)2 |

|||||

| Rochester Youth Development Study |

Sohoni et al. (2014) | 638 male Rochester public school students born ca. 1973–1975 |

31–33 | Arrest records, adulthood at 25 years of age |

3852 | 60% | 335 | 87% | 50 | 13% |

| Stockholm Birth Cohort | Nilsson et al. (2013) | 13,715 Swedish males and females born in 1953 |

48 | Police-registered crime |

1,759 | 13% | 812 | 46% | 947 | 54% |

| Retrospective/offender only studies published from 1999 forward, not included in Eggleston & Laub (2002) | ||||||||||

| Colorado bond commissioner processing |

DeLisi (2006) | 500 male and female frequent offenders with intake in Colorado from 1995–2000 |

Mean age of 40 |

Criminal records and self-reports |

500 | 100% | 192 | 38% | 308 | 62% |

| Baltimore City Detention Center |

Simpson, Yahner, & Dugan (2008) | 351 adult females incarcerated in Baltimore |

Mean age of 35 |

Self-reports | 342 | 100% | 156 | 46% | 186 | 54% |

| Southwestern prison | Gunnison & McCartan (2010) | 131 adult females incarcerated in a Southwestern prison |

25 to 44 | Self-reports | 131 | 100% | 55 | 42% | 76 | 58% |

| Three-year statewide classification study |

Harris (2011) | 3,598 males and females sentenced to felony probation in a large south central US state during October 1993 |

48 | Criminal records | 3,598 | 100% | 481 | 13% | 3,117 | 87% |

| Life history interviews | Carr & Hanks (2012) | 30 females incarcerated in a local jail |

26 to 55 | Official convictions and self-reports |

30 | 100% | 22 | 73% | 8 | 27% |

| Swedish Project Metropolitan |

Andersson et al. (2012) | 518 females with a criminal record in Stockholm, Sweden |

30 | Crimes known to police, including nonminor traffic |

10% (est)2 | |||||

| 1983–84 Queensland Longitudinal Data Cohort |

Thompson et al. (2014a) | 40,523 male and female offenders |

25 | Youth and adult court finalizations, youth police cautions |

40,5232 | 100% | 19,310 | 48% | 21,213 | 52% |

Notes:

- Sources reporting only results from group-based trajectory models are excluded.

– This figure is estimated based on group-based trajectory modeling.

– This figure includes juvenile-only offenders; the percentage of adult-onset offenders is thus across the entire offender group. In these cases the proportion of adult-onset offenders among adult-offenders is likely greater than the figure reported in the final column.

There are both practical and theoretical reasons for investigating the official age of onset of crime. Practically, adult-onset offenders represent a sizable proportion of official offenders and warrant an appropriate response from the criminal justice system, ranging from targeted interventions to increasing the age limit for processing within the juvenile justice system. Adult-onset offenders also pose challenges to life-course developmental theories, which have generally not anticipated the existence of the adult-onset offender (DeLisi & Piquero, 2011). Examination of the adult-onset offender may lead to important theoretical insights about the origins of criminal behavior (Piquero, Oster, Mazerolle, Brame, & Dean, 1999; Thornberry & Krohn, 2011).

In this study, we investigated adult-onset offending. We used data from the Dunedin Longitudinal Study which has followed a 1972–73 birth cohort for four decades in New Zealand. Based on past research (see Table 1), we anticipated finding official adult-onset offenders in the Dunedin cohort. We additionally sought to find the presence of an official “social-adulthood-onset offender” – someone who is first convicted at or after 25 years of age – based on the idea that modern-day adolescence is prolonged (Arnett, 2000). First, we tested whether official adult-onset offenders had an unofficial history of criminal behavior, as has been found in past studies (see, for example, McGee & Farrington, 2010; Sohoni et al., 2014). Going beyond these studies, we examined the unofficial history of criminal behavior among adult-onset offenders back to early childhood using multiple reporting sources (self, parents, teachers, and police). Second, we tested whether the types of crime for which official adult-onset offenders were convicted could illuminate potential causes of official adult-onset offending. Third, because most official-adult onset offenders had a history of antisocial behavior we were able to add a fresh conceptualization of how theories originally designed to predict de novo adult-onset offending could be extended to explain a first official conviction during adulthood. We examined 10 specific hypotheses derived from theories on adult-onset offending that could explain why some people appear to be adult-onset offenders, or are first detected during adulthood. By testing these 10 hypotheses in a single, contemporary cohort we were able to go beyond previous studies, unifying the literature on adult-onset offending and drawing a comprehensive picture of the typical adult-onset offender. We conclude by discussing policy responses to adult-onset offenders and the theoretical implications of adult-onset offending for life-course criminology.

Previous evidence on adult-onset offenders

In Table 1, we present evidence of adult-onset offending found in previous prospective and retrospective studies on adult-onset offenders. The 35 analyses used 25 unique datasets, 19 of which were from the United States. Of the 35 analyses, 4 used the Cambridge Study of Delinquent Development (CSDD). Studies of contemporary cohorts beyond the CSDD and from outside of the USA would help to address generalizability of descriptive data about adult-onset offending. The percentage of adult-onset offenders varied widely across the studies, from 6% to 87%, likely due to methodological heterogeneity. For example, the analytic samples ranged from 30 to over 300,000, and used different sexes, ages, and definitions of offending (14 analyses used official criminal conviction). A few studies (noted in Table 1) included juvenile-only offenders in the denominator, which likely meant that the percent of adult-onset offenders among adult offenders, reported in the final column, was underestimated. Together the studies provide important and robust evidence that adult-onset offenders should be found in studies of criminal behavior, regardless of the period or location from which the data come, the age to which the subjects are followed, or the measure of criminal behavior used. However, due to wide variation in methods, it is difficult to synthesize across these studies to extract a picture of the adult-onset offender. Moreover, previous studies testing explanations of adult-onset offending tended to focus on only one or two explanations, possibly due to data constraints. It thus remains unclear whether existing theories of crime can achieve a coherent picture of the adult-onset offender. To achieve a more coherent profile, it is important to test all hypotheses that have been put forward simultaneously in the same sample.

Age of onset in official and self-reported data

Criminal justice system data often overestimate the age of onset of criminal offending. Members of the Dunedin cohort, in the present study, self-reported an abundance of violence, theft, and substance offenses during adolescence (Moffitt et al., 2001). Officially, however, only 15 percent of the cohort had, by 22 years of age, ever been convicted of a crime (Moffitt et al., 2001). Among the self-reported adolescent offenders in the CSDD, only about half were officially recorded as offenders (Farrington et al., 2007). Additionally, CSDD boys’ official age of onset was, on average, five years later than their self-reported age of onset of crime (Theobald & Farrington, 2014). Among men from the Rochester Youth Development Study who had never been arrested by 32 years of age, over three-quarters had self-reported some type of offense by 18 years of age, and around half had self-reported a violent or serious offense by 18 years of age (Sohoni et al., 2014). This pattern of early onset and later conviction is unsurprising. Most people, it has been argued, engage in criminal behavior during adolescence (Moffitt, 1993), yet a minority of people acquire a criminal record during adolescence. Criminal conviction, an indication that the individual is legally responsible for a crime, requires both apprehension by police and successful prosecution. Successful detection and prosecution of all criminal behavior is, however, impossible (Mosher, Hart, & Miethe, 2011). Official data, thus, appear inadequate for capturing the age of onset of criminal behavior.

Official data may also overestimate the age at which criminal behavior begins because the criminal justice system is constrained by a lower age bound. Children below a certain age, usually ranging between 10 and 15 years, cannot be held liable and convicted for criminal behavior. Prospective identification of offenders is controversial, yet it is instructive to consider whether the typical adult-onset offender was also antisocial as a child or just lagging behind juvenile-onset offenders in their antisocial development. Some studies suggest that the typical official adult-onset offender’s childhood antisocial behavior looks similar to that of the typical official juvenile-onset offender (Pulkkinen, Lyyra, & Kokko, 2009; Zara & Farrington, 2013). Thus, relying on official data may obscure important information regarding early childhood antisocial behaviors and, ergo, the development of antisocial behavior over the life-course of adult-onset offenders.

We tested the hypothesis that many official adult-onset offenders engage in antisocial behavior from early life. Many past studies incorporating unofficial sources have only included self-report data during adolescence (with the notable exception of the CSDD), preventing insights on the development of antisocial behavior among adult-onset offenders. We extend beyond past research by analyzing reports of unprosecuted antisocial behavior from parents, teachers, the police, and self-reports from childhood onwards.

Adult-onset offenders’ offense specialization and extent of offending

Offenders are known to commit a variety of types of crime, but tend towards offenses with utilitarian motivations, such as theft and fraud, as they age (Farrington, 2014; Laub & Sampson, 2003; Massoglia, 2006; Piquero et al., 1999; Stattin, Magnusson, & Reichel, 1989). Adult-onset offenders, in particular, may be more specialized than juvenile-onset offenders because of their limited criminal experience and established routines with regular antisocial opportunities (Catalano et al., 2005; Farrington, 2014). Adult-onset offenders may also gravitate towards sexoffending as they age (Lussier, Tzoumakis, Cale, & Amirault, 2010). To our knowledge, only one study has explicitly compared all conviction types between adult-onset and juvenile-onset offenders (McGee & Farrington, 2010). This study found that compared to juvenile-onset offenders, adult-onset offenders, committed proportionally more fraud, theft from work, vandalism, and sex crimes (McGee & Farrington, 2010). However, adult-onset offenders, appear to maintain an overall lower level of offending than juvenile-onset high-chronic offenders, even during the same adult age-period (Andersson, Levander, Svensson, & Levander, 2012; Broidy et al., 2015; Chung, Hill, Hawkins, Gilchrist, & Nagin, 2002; van der Geest, Blokland, & Bijleveld, 2009). Adult-onset offenders’ crime specialization may indicate causes of their criminal activity and could also have implications for justice-system policy (Piquero et al., 1999). We tested whether certain types of criminal convictions were relatively more likely among official adult-onset offenders, compared to official juvenile-onset offenders, and we compared the frequency of convictions between official onset-groups.

Explanations for official adult-onset offending

Eggleston and Laub (2002) summarized the then-current state of criminological theory and research on adult-onset offenders. Many theories of crime over the life course denied the existence of the adult-onset offender. Yet, adult-onset offenders seemed to appear in many studies (see Table 1) and it was argued that the adult-onset offender warranted systematic study. With the theoretical foundation from which to study the adult-onset offender under-developed, researchers sought to apply established theories to the adult-onset offender and new theories, which could better incorporate adult-onset offending, emerged. This lead us to identify two sets of theories of the adult-onset offender (Farrington, 2006; Sohoni et al., 2014).

The first set of theories emphasized early-life influences on offending at any time in the life-course. These theories implied that true adult-onset antisocial behavior was highly unlikely because antisocial behavior was thought to develop during childhood and adolescence under the influence of both early-emerging individual characteristics (such as low intelligence and low self-control) and family influences (including low socioeconomic status). Examples of theories in this set are Gottfredson & Hirschi’s (1990) general theory of crime and Moffitt’s (1993) dual taxonomy. According to these theories the rare adult-onset offender was likely to have followed a non-traditional path of development. For example, Moffitt hypothesized that young males who abstained from crime while at the peak age of crime participation must have personal characteristics, such as social timidity or inhibition that reduced their opportunities to take part in the normative law-breaking activities of delinquent peer groups. This implies that any offender who first initiates crime as an adult will have, as a juvenile, been socially inhibited and will have lacked delinquent peers.

The second set of theories emphasized situational influences on offending during adulthood. These theories implied that adult-onset antisocial behavior could begin in earnest during adulthood due to changes in the social environment. The major life-course theories that fell under this paradigm were Farrington’s (2006, 2011) integrative cognitive antisocial potential, Catalano & Hawkins’ (1996) social development model (see also Catalano et al., 2005), LeBlanc’s integrated multilayered control theory (1997), Sampson & Laub’s (1993) age-graded theory of informal social control, Thornberry (1987)/Thornberry & Krohn’s (2011) interactional theory, and Wikström’s situational action theory (2004, 2005). Like the aforementioned developmental theories, these theories did not explicitly describe the process of adult-onset offending. However, the situational influences they emphasize also allow for offending to begin after the peak age of crime, during adulthood. For example, Sampson and Laub’s age-graded theory of informal social control would predict that adult-onset offenders result from a lack of social bonds during adulthood. These theories can also be applied to explain why anyone might be detected and convicted at any age; for example, conditions that tend to onset in adulthood such as alcoholism or mental illness might result in offending that is more publicly visible and attracts the attention of police. Since the applicability of developmental and situational theories to adult-onset offending has already been explicated (see, for example, Farrington, 2006; Sohoni et al., 2014) we are left with how to reconcile these theories in light of evidence that many official adult-onset offenders have a history of undetected antisocial behavior. Developmental and situational theories may be best put to use to explain how an individual may persist in and first be detected for antisocial behavior during adulthood.

We have developed hypotheses based on these two sets of theories of the adult-onset offender and past evidence on adult-onset offending. Hypotheses under the first set of theories must explain why or how official adult-onset offenders avoided an early official criminal record, despite engaging in criminal behavior as adolescents. These hypotheses distinguish official adult-onset offenders from official juvenile-onset offenders (that is, from offenders who were first convicted during adolescence).

Hypothesis 1: Official adult-onset offenders, compared to juvenile-onset offenders, report fewer offenses during adolescence

Blumstein and Cohen (1987) argued that the more offenses one commits, the greater the likelihood of being captured. Official adult-onset offenders may avoid detection and prosecution by committing a relatively small number of offenses. Official adult-onset offenders from the CSDD, compared to official juvenile-onset offenders, had self-reported fewer offenses as boys (Kazemian & Farrington, 2005; McGee & Farrington, 2010; Zara & Farrington, 2010), which appeared to reduce their likelihood of acquiring a juvenile record (Farrington et al., 2007).

Hypothesis 2: Official adult-onset offenders, compared to juvenile-onset offenders, come from families with higher socioeconomic status

Critical criminological theory argues that with higher socioeconomic class comes the privilege of avoiding a criminal record. Perhaps the best example of this privilege is shown in Chambliss’ (1973) classic “The Saints and the Roughnecks”, in which the high socioeconomic status Saints frequently offended but were never arrested. Official adult-onset offenders may enjoy the protection of their high socioeconomic status families during adolescence. This benefit may fade with the transition to adulthood. Some evidence indicates that adult-onset offenders, compared to juvenile-onset offenders, may be less likely to come from a low-income family (Zara & Farrington, 2010).

Hypothesis 3: Official adult-onset offenders, compared to juvenile-onset offenders, are more intelligent

Low intelligence is a well-known risk factor for juvenile-onset offending (Farrington, 2011). Official adult-onset offenders may be more intelligent than juvenile-onset offenders and, consequently, more successful at evading detection and prosecution. Some research has supported the idea that later-age official onset of offending is tied to higher intelligence (Bellair, McNulty, & Piquero, 2014; Zara & Farrington, 2010).

Hypothesis 4: Official adult-onset offenders, compared to juvenile-onset offenders, have fewer delinquent peers during adolescence

Attachment to delinquent peers is known to increase the individual risk of delinquency (Laub & Sampson, 2011), and may also increase the likelihood of serious group offending and the risk of apprehension and conviction (Erickson, 1973; Tillyer & Tillyer, 2014). For adolescents who are already delinquent, research has shown, joining with delinquent peers further exacerbates criminal behavior (Thornberry & Krohn, 1997; Vitaro, Tremblay, & Bukowski, 2000). Official adult-onset offenders may have relatively few delinquent peers and, thereby, avoid detection and apprehension as juveniles. Evidence from the CSDD supports the hypothesis that adult-onset offenders have fewer delinquent friends (Zara & Farrington, 2009, 2010).

Hypothesis 5: Official adult-onset offenders, compared to juvenile-onset offenders, are more likely to be socially inhibited

Socially inhibited people are timid and withdrawn. Adolescents tend to offend in the company of others (Farrington, 2011), an activity that social inhibition could curb. Socially inhibited adolescents may be excluded from their peer groups, including delinquent peer groups, and, thereby, be insulated from group crime (Moffitt, 1993, p. 689; Owens & Slocum, 2015; Theobald & Farrington, 2014, p. 3338). Such insulation could reduce the risk of apprehension and detection. Official adult-onset offenders may be socially inhibited, which excludes them from high-risk group offending. Research has shown that social inhibition may be related to adult-onset offending (Zara & Farrington, 2009).

Hypotheses under the second set of theories, though often initially meant to explain de novo adult offending, must explain why adult-onset offenders first get caught, prosecuted, and convicted during adulthood. We test an additional set of 5 hypotheses that seek to explain why people without a juvenile criminal record would acquire a record during adulthood. These hypotheses distinguish official adult-onset offenders from official non-offenders (that is, from people who are non-criminal, or who continue to avoid apprehension or conviction).

Hypothesis 6: Official adult-onset offenders, compared to official non-offenders, report more offenses during adulthood

As in hypothesis one (above), a high level of offending is likely to increase the risk of detection and capture (Blumstein & Cohen, 1987). Official adult-onset offenders, compared to official non-offenders, may be offending at relatively high rates. Additionally, a low-rate adolescent offender who avoided a criminal record as a juvenile but continued offending as an adult, may find his or her luck run out. This hypothesis implies adult-onset offenders will self-report more offenses as adults compared to non-offenders.

Hypothesis 7: Official adult-onset offenders, compared to official non-offenders, are more likely to have adult-onset schizophrenia or bipolar disorder

Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder can cause people to become disconnected from reality and have abnormal thoughts. These mental health problems often begin during the transition from late adolescence to early adulthood, and have been connected to greater risks for crime (Arseneault, Moffitt, Caspi, Taylor, & Silva, 2000; Fazel, Långström, Hjern, Grann, & Lichtenstein, 2009; Fazel, Lichtenstein, Grann, Goodwin, & Långström, 2010). Individuals with schizophrenia and manic symptoms of bipolar disorder show disorganized behavior and often attract public attention. Official adult-onset offenders may have adult-onset schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, which increases their risk of apprehension and conviction for crime. There is some evidence of official adult-onset offending being connected to these types of mental health disorders (Elander et al., 2000; Farrington, 1989; Zara & Farrington, 2010, 2013).

Hypothesis 8: Official adult-onset offenders, compared to official non-offenders, are more likely to be dependent on alcohol or other substances

Alcohol dependence tends to peak between the ages of 18 and 20 years (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2008), and hard drug use and dependence tend to peak about two years later (Wagner & Anthony, 2002). Alcohol dependence in adulthood is related to more criminal convictions (Meier et al., 2013) and drug dependence, in particular, may be a reason for offending (Mumola & Karberg, 2006). People with drug and alcohol problems may be unsuccessful at transitioning to stable adult roles with strong informal social controls (Thornberry, 2005), which could extend criminal behavior into adulthood. Additionally, drug and alcohol dependence may lead to erratic public behavior, drawing public attention and increasing the risk of apprehension and conviction for crime. Official adult-onset offenders may be dependent on alcohol or substances during adulthood, which increases their risk of apprehension for crime. Some research has supported the connection between late-onset crime and substance dependence (Elander et al., 2000; Farrington, 1989; Pulkkinen et al., 2009; Zara & Farrington, 2010).

Hypothesis 9: Official adult-onset offenders, compared to official non-offenders, have weaker intimate-partner attachment bonds

Intimate relationships, as argued by the age-graded theory of informal social control, are an important mechanism in discouraging crime (Laub & Sampson, 2003; Sampson & Laub, 1993). Good quality intimate relationships may also discourage crime (Giordano, Schroeder, & Cernkovich, 2007). Serious intimate relationships usually begin during adulthood and may curb adolescent antisocial behavior. Official adult-onset offenders may have weak adult intimate-partner attachment bonds, which increases their risk of apprehension and conviction for crime. Some evidence has indicated that ending a marital relationship contributes to adult-onset crime (Kivivuori & Linderborg, 2010). Other research has shown that adult-onset offenders were generally less likely to be in a romantic relationship (Mata & van Dulmen, 2012).

Hypothesis 10: Official adult-onset offenders, compared to official non-offenders, have a lower expectation of informal sanctions from actors and institutions

The expectation of informal sanctions from actors and institutions such as friends, family, partners, and employers, may deter criminal behavior (Laub & Sampson, 2011). As people become more free and independent with the transition to adulthood, they may perceive that such actors and institutions will have weakening reactions to criminal behavior; this may be especially true among people who become cut-off from education and social services (Krohn, Gibson, & Thornberry, 2013; Osgood, Foster, & Courtney, 2010; Thornberry, 2005). Official adult-onset offenders may perceive weak informal social control during adulthood, which increases their risk for apprehension and conviction for crime. Research has shown that late-onset crime is related to loss of or mild informal sanctions (Kivivuori & Linderborg, 2010; Mata & van Dulmen, 2012; Sampson & Laub, 1993; Zara & Farrington, 2010).

Data

Data source

We analyzed adult-onset criminal offending among participants of the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study, a longitudinal investigation of health and behavior in a representative birth cohort (Poulton, Moffitt, & Silva, 2015). Study participants (N=1,037; 91% of eligible births; 52% male) were all of the individuals born between April 1972 and March 1973 in Dunedin, New Zealand (NZ), who were eligible for the longitudinal study based on residence in the province of Otago, and who participated in the first assessment at age 3. The cohort represents the full range of socioeconomic status on NZ’s South Island and matches the NZ National Health and Nutrition Survey on adult health indicators (e.g., BMI, smoking, GP visits). Study participants were primarily white; fewer than 7% self-identified as having partial non-white-European ancestry, matching NZ’s South Island. Assessments were carried out in phases at birth and ages 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 18, 21, 26, 32, and, most recently, 38 years, when 95% of the 1,007 Study participants still alive took part. At each assessment, each Study participant (including outmigrants) is brought to the University of Otago research unit for a full day of interviews and examinations. Assessments also include data from parents, teachers, and informants chosen by the Study participant as someone who knew them well. Data also include linkage to administrative record data sets. To be included in the present report, Study participants had to have either been convicted of a crime in NZ, or survived to phase 38 data collection and lived in NZ as an adult. Our analytic sample of 931 Study members excludes 106 people from the original Study whom we could not definitively consider to be non-offenders through adulthood because of death (n = 24), outmigration (n = 42), long-term missing to the Study (n = 31), or refusal to allow the phase 38 records search (n = 9). As such, the 931 Study participants included in this report either appeared in the conviction records or survived to the phase 38 records search and lived in NZ without a conviction.

Variables

The Dunedin Study contains extensive information about the Study participants relevant to examining adult-onset offending. Table 2 provides information about the variables that we examined, including descriptive statistics by sex.

Table 2.

Variables used in the analysis of adult-onset offending in the Dunedin cohort and their frequency distributions, by sex

| Variable | Description | Males (n=484) |

Females (n=447) |

|---|---|---|---|

| %/Mean (SD) | %/Mean (SD) | ||

| Official criminal conviction | |||

| Criminal conviction | Dichotomous indicator of a conviction for crime. | 42.2% | 14.8% |

| Age at first conviction | Age at which first criminal conviction occurred, among convicted Study participants. |

19.46 (4.36) | 20.85 (5.96) |

| Unprosecuted, pre-adult antisocial behavior | |||

| Evidence of antisocial behavior during childhood | |||

| Parent & teacher reports of childhood antisocial behavior |

Scale of parent and teacher reports of participant antisocial behaviors averaged across ages 5, 7, 9 and 11. The composite scale ranged from 0 to 8, with one point allocated for endorsement for each of the following items about the participant’s behavior: destroys property, fights, disliked by other children, irritable, disobedient, tells lies, steals, bullies others. |

1.72 (1.39) | 1.22 (1.03) |

| Evidence of antisocial behavior during adolescence | |||

| Conduct disorder, age 11– 18 |

Dichotomous indicator of conduct disorder. Conduct disorder was measured according to the symptom criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), which identify adolescents displaying a persistent pattern of behavior that violates the rights of others, including physical harm. A diagnosis of conduct disorder (using a 12-month reporting period for symptoms) was made at each of four ages: ages 11, 13, 15, and 18. Study participants were recorded as having conduct disorder if five or more conduct disorder symptoms were reported at any of the four waves. |

29.0% | 14.9% |

| Any self-reported offenses: |

|||

| Age 13 | Dichotomous indicator of any one or more of thirteen types of self-reported offenses that were consistently measured at ages 13, 15, and 18. The types of offenses were: running away overnight (runaway), carrying a hidden weapon (hidden weapon), purposefully destroying or damaging property (vandalism), purposefully setting fire to a building (arson), breaking into a building to steal something (breaking & entering), theft, taking something from a store without paying for it (shoplifting), theft from a vehicle, taking a car without permission and without intent to keep it (joy-riding), stealing or attempting to steal a car or motorcycle (vehicle-theft), robbery, possessing marijuana, possessing harder drugs. |

37.3% | 20.6% |

| Age 15 | 47.4% | 35.4% | |

| Age 18 | 59.4% | 48.6% | |

| Age 13–18 | 75.3% | 61.1% | |

| Evidence of police contact as an adolescent up to age 18 | |||

| Parent-reported police contact, age 13–15 |

Dichotomous indicator of parent-reported contact with the police. The parent reported whether the child had been in trouble with the police between the ages of 13 and 15 at the age 15 interview. |

10.4% | 5.7% |

| Police-recorded arrest before age 18 |

Dichotomous indicator of police recorded arrest, obtained by hand search of Youth-Aid Constable records held by the Dunedin Police. |

19.8% | 10.1% |

| Variables used to test explanations of first conviction during adulthood | |||

| Hypotheses of how those first convicted as an adult evaded adolescent prosecution | |||

| Extent of self-reported offenses: |

|||

| Age 13 | Continuous measure of one or more of 13 types of self-reported offenses that were consistently measured at ages 13, 15, and 18: runaway, hidden weapon, vandalism, arson, breaking & entering, theft, shoplifting, theft from a vehicle, joy- riding, vehicle-theft, robbery, possessing marijuana, and possessing harder drugs. |

0.75 (1.44) | 0.34 (0.79) |

| Age 15 | 1.25 (2.15) | 0.88 (1.59) | |

| Age 18 | 1.61 (2.23) | 0.86 (1.35) | |

| Family socioeconomic status (SES), age 1–15 |

The socioeconomic status of Study members’ parents was measured with the Elley-Irving scale (Elley & Irving, 1976) which assigned occupations into 1 of 6 SES groups (from 1 = unskilled laborer to 6 = professional). The higher of either parents' occupation was averaged spanning the period from Study members’ birth to age 15 (1972–1987). |

3.73 (1.13) | 3.79 (1.11) |

| Childhood IQ, age 7–11 | Assessed using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children Revised (WISC-R) (Wechsler, 1974). IQ scores for ages 7, 9 and 11 were averaged and standardized. |

100.47 (15.04) | 99.63 (14.06) |

| Delinquent Peers, age 13 & 15 |

Measure of delinquency in company of peers at ages 13 and 15. Mean number of parent's affirmative responses to 10 questions about whether the Study participant: steals in the company of others, belongs to a gang, is loyal to delinquent friends, truants from school in the company of others, has "bad companions", uses drugs in company of others, is part of a group that rejects school activities, drinks alcohol in company of others, admires/associates with rougher peers, and admires people who operate outside the law. The scale ranged from 0 to 10. |

0.90 (1.51) | 0.83 (1.30) |

| Social potency at age 18 | Social potency was assessed via the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ) at the age 18 interview. People with low social potency are likely to be timid and socially withdrawn; they prefer not to be active in a group with others. The original scale ranged from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater social potency. |

39.45 (24.17) | 34.73 (23.24) |

| Hypotheses of why those first convicted as an adult began getting caught during adulthood | |||

| Extent of self-reported offenses: |

|||

| Age 21 | Continuous measure of one or more of 48 types of self-reported offenses that were consistently measured at ages 21, 26, 32, and 36. Four main types of offenses were assessed: property offenses, rule offenses, drug related offenses, and violent offenses. Property offenses included 20 items such as vandalism, breaking and entering, motor vehicle theft, embezzlement from work, shoplifting, several other kinds of thefts, and several kinds of frauds. Rule offenses included 13 items such as careless and reckless driving, public drunkenness, obstructing the work of the police, soliciting or selling sex, giving false information on a tax form, loan application or job application, and disobeying the courts. Drug-related offenses included 4 items about using and selling various types of illicit drugs. Violent offenses included 6 items about simple assault, aggravated assault, gang fighting, robbery, arson, and forced sex. Hitting a child was also assessed with 2 questions about hitting or otherwise hurting a child out of anger, with follow-up questions ruling out situations of physical discipline. The scale ranged from 0 to 26, with higher numbers indicating greater involvement in crime. |

4.22 (4.01) | 1.85 (1.98) |

| Age 26 | 3.06 (3.03) | 1.44 (1.63) | |

| Age 32 | 1.61 (2.21) | 0.72 (1.25) | |

| Age 36 | |||

| Schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, age 21–38 |

Dichotomous indicator of a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, assessed at ages of 21, 26, 32, and 38. |

4.5% | 4.5% |

| Alcohol or substance dependence: |

|||

| Alcohol dependence, age 21–38 |

Dichotomous indicator of Study participants’ persistent dependence on alcohol or drugs assessed between ages 21 and 38. Respondents were asked questions which tapped into DSM criteria for dependence on alcohol and drugs. Respondents were noted as having a persistent history of alcohol or drug dependence if they had two or more waves with a diagnosis of dependence for each type. |

17.0% | 6.3% |

| Drug dependence, 12.8% age 21–38 |

12.8% | 4.9% | |

| Months living with spouse or partner, age 21–38 |

Number of months reported living with spouse or de facto partner between 21 and 38 years of age. Calculated from |

114.08 (57.78) |

128.29 (59.76) |

| Very happy with relationship: |

|||

| Age 21 | Dichotomous indicator of whether participant was happy with their relationship. Asked only of those in any relationship during the past year. Study participants were asked about their overall happiness with their partner at ages 26 and 32. Respondents replied that they were either “unhappy”, “somewhat happy” or “very happy.” The majority of respondents indicated that they were very happy with their relationship and the measure was dichotomized into “very happy” and other. |

72.2% | 76.9% |

| Age 26 | 76.2% | 80.1% | |

| Age 32 | |||

| Informal sanctions, ages 21 and 26, from: |

|||

| Friends | Scale of perceived informal consequences. Study participants were asked “Would you lose the respect and good opinion of your close friends if they found out that you…?”, “Would you lose the respect and good opinion of your parents and relatives if they found out that you…?”, “Would it harm your chance to attract or keep your ideal partner if people knew that you…?”, “Would it harm your future job prospects if people knew that you…?”. Crimes queried were shoplifting, drug use, car theft, partner violence, assault, burglary, drunk driving, and using a stolen bank card. Responses were coded 2=yes, 1=maybe, 0=no. These questions were asked at ages 21 and 26. |

8.49 (3.47) | 10.15 (3.19) |

| Parents | 12.53 (2.57) | 13.24 (2.29) | |

| Partner | 10.36 (3.14) | 10.54 (3.32) | |

| Employers | 12.83 (2.05) | 13.30 (1.70) | |

| All | 44.19 (8.82) | 47.24 (8.54) | |

Adult-onset conviction

We defined adult-onset offending as an initial criminal conviction at or after 20 years of age, the age of legal majority in NZ from 1970 to the time of the last records search. The age of majority has often been used as the cutoff point in criminological studies of adult-onset offending. Research in developmental psychology, however, has suggested that contemporary cohorts have a protracted adolescence and gradually transition to adulthood during their mid-twenties (Arnett, 2000). Arnett’s concept of “social adulthood” has been incorporated in criminological theory (Thornberry, 2005), and at least one study on adult-onset offending has used Arnett’s concept and operationalized adulthood as beginning at 25 years of age (Sohoni et al., 2014). Consequently, we also analyzed a group of offenders who met the definition of social-adulthood-onset, defined as an initial criminal conviction at or after 25 years of age.

We used the participants’ first official criminal conviction as a measure of the age of onset of official criminal offending, a standard used in many past studies of adult-onset offending (see Table 1). Official criminal conviction records have the advantage of being unambiguous with regard to both the occurrence of a crime and the age of conviction. We obtained information about criminal convictions by searching the central computer system of the New Zealand Police, which provides details of all New Zealand convictions and sentences and Australian convictions communicated to the New Zealand Police. We conducted searches following the completion of each assessment at ages 21, 26, 32, and 38 (search completed in 2013). Official records of criminal conviction were available from 14 years of age onwards, the age from which criminal conviction was permissible. We tabulated criminal convictions from both youth and adult courts by grouping charges according to general types of crime (see Appendix 1).

Evidence of antisocial behavior before adulthood

To test whether official criminal conviction represented the ‘true’ onset of antisocial behavior we examined various measures of the Study participants’ unprosecuted, pre-adult antisocial behavior and police contact. We analyzed (a) reports of participants’ childhood antisocial behavior made by teachers and parents; (b) diagnoses of conduct disorder made in adolescence; (c) self-reports of juvenile delinquency; (d) parent-reports of police contact during adolescence; and (e) Study participants’ contact with police prior to age 17 as recorded on the “333 form” completed by officers after each arrest and held by the Dunedin Police. The 333 form was used by NZ police, while the Study members were growing up, to register police diversion from formal prosecution to an informal process managed by a youth constable.

Proposed causes of adult-onset conviction

We examined variables that tapped into ten hypotheses about adult-onset offending. The first five hypotheses explained why adolescent offenders may have been able to evade prosecution prior to a first conviction in adulthood. These hypotheses included fewer self-reported offenses, higher socioeconomic status, higher intelligence, fewer delinquent peers, and lower scores on a personality trait called “social potency.” The remaining five hypotheses explained why people may have offended and been apprehended for crime for the first time during adulthood. These hypotheses included more self-reported offenses; schizophrenia or bipolar disorder; substance dependence (alcohol or drugs); weak intimate-partner attachment; and self-perceived low risk of informal sanctions of crime. We analyzed a number of variables, detailed in Table 2, to test these hypotheses.

Analytical approach

Our analyses of the adult-onset offender aimed to answer four main questions: 1) Are there official adult-onset offenders in the Dunedin cohort? 2) Does adult-onset conviction indicate adult-onset antisocial activity? 3) Do adult-onset offenders tend to be convicted for different types of crimes compared to juvenile-onset offenders? 4) Which theories can explain adult-onset conviction? We answered these questions through bivariate hypothesis-testing analyses, comparing the official adult-onset offender group to the official non-offender group and/or official juvenile-onset offender group on various aspects. Bivariate analysis was an appropriate modeling choice as each test tied into a specific hypothesis about how the official adult-onset offender group compared to the non-offender or official juvenile-onset offender group. The analyses could be straightforward because none of our theory-derived hypotheses specified that a given construct alters the probability of crime in the absence of another factor, or while in interaction with another factor.

Results

Are there adult-onset offenders in the Dunedin birth cohort?

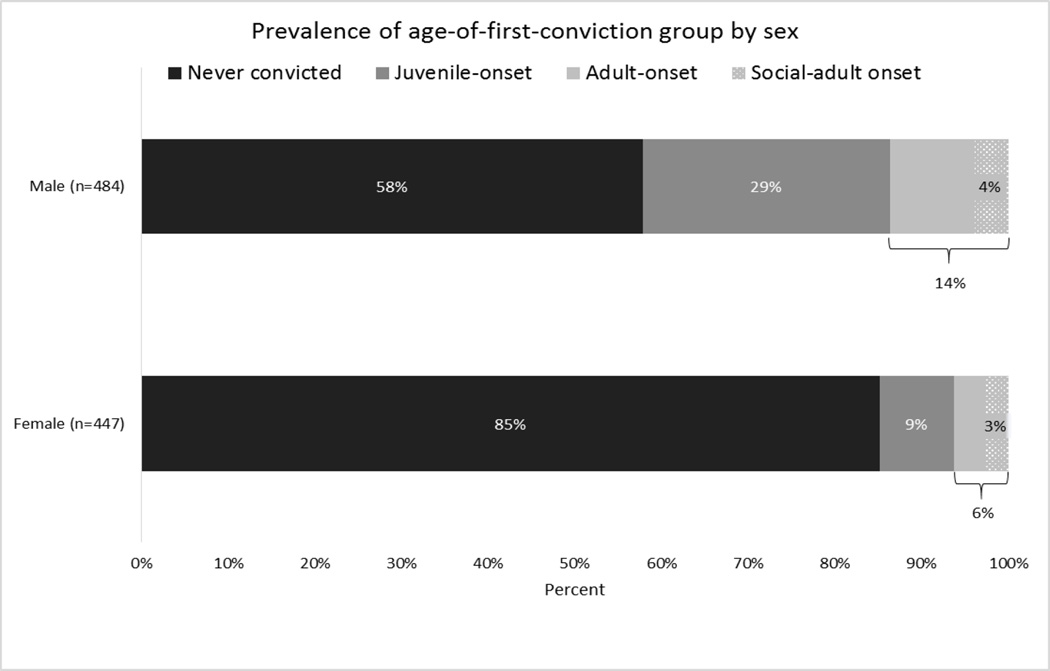

Table 3 shows descriptive information on the participants of the Dunedin Study grouped by age at first conviction for males and females, separately. We found a substantial male official adult-onset offending group. Of the male Study participants, 14% were first convicted during adulthood, at or after 20 years of age, as of the latest search of criminal justice system records in 2013, when Study participants were approximately 40 years of age. Official adult-onset men represented about one-third of convicted men in the Study. Male official adult-onset offenders were, on average, first convicted around 24 years of age. The oldest age at first conviction was 37 years; second and later convictions occurred through 40 years of age. Male official adult-onset offenders had, on average, 4 lifetime convictions each, and their convictions accounted for 15% of the men’s total convictions.

Table 3.

Description of Study participants as a function of sex and conviction status

| Men | Women | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never convicted1 |

Juvenile- onset2 |

Adult- onset3 |

Social- adulthood- onset subset4 |

Never convicted1 |

Juvenile- onset2 |

Adult- onset3 |

Social-adult hood-onset subset4 |

|

| Participant-level descriptive statistics | ||||||||

| Number of Study participants | 280 | 138 | 66 | 20 | 381 | 38 | 28 | 12 |

| Percentage of Study participants | 57.9% | 28.5% | 13.6% | 4.1% | 85.2% | 8.5% | 6.3% | 2.7% |

| Percentage of offenders | N/A | 67.7% | 32.4% | 9.8% | N/A | 57.6% | 42.4% | 18.2% |

| Mean age at first conviction (std dev) |

N/A | 17.14 (1.32) | 24.29 (4.55) | 30.15 (3.80) | N/A | 17.03 (1.17) | 26.04 (5.93) | 31.92 (4.36) |

| Median age at first conviction | N/A | 17 | 22.50 | 30 | N/A | 17 | 22.50 | 32 |

| Maximum age at first conviction | N/A | 19 | 37 | 37 | N/A | 19 | 38 | 38 |

| Mean lifetime convictions per participant (std dev) |

N/A | 11.92 (20.33) | 4.24 (6.97) | 2.35 (2.64) | N/A | 8.42 (13.69) | 2.93 (2.98) | 3.42 (2.61) |

| Conviction-level descriptive statistics | ||||||||

| Number of convictions | N/A | 1,643 | 279 | 47 | N/A | 320 | 82 | 41 |

| Percentage of Study participants’ total convictions |

N/A | 85.5% | 14.5% | 2.5% | N/A | 79.6% | 20.4% | 10.2% |

Notes:

-No conviction by age 40 years.

-First conviction age 14 to 19 years.

-First conviction age 20 years and above. The adult-onset group also includes the social-adulthood subset.

-First conviction age 25 years and above.

Of the male Study participants, only 4% were in the official social-adulthood-onset offender subset, first convicted at or after 25 years of age. Official social-adulthood-onset offenders represented one-tenth of convicted men. Male official social-adulthood-onset offenders were, on average, first convicted around 30 years of age. Male official social-adulthood-onset offenders had, on average, only 2 lifetime convictions each and the convictions of this subset of official adult-onset offenders accounted for only 3% of the cohort men’s total convictions.

Of the male Study participants, 29% were official juvenile-onset offenders, convicted before 20 years of age, the age of legal majority in NZ. Official juvenile-onset offenders represented two-thirds of convicted men in the Study. Male official juvenile-onset offenders were first convicted, on average, around 17 years of age, with second and later convictions occurring through 39 years of age. The official juvenile-onset men had, on average, 12 lifetime convictions each, and their convictions accounted for 85% of the men’s total convictions.

The majority of male Study participants, 58%, had not been convicted of a crime (“never convicted”).

Of the female Study members, 6% were first convicted in adulthood. Official adult-onset women represented nearly half of the convicted women in the Study. Female official adult-onset offenders were, on average, first convicted at 26 years of age. The oldest age at first conviction was 38 years; second and later convictions occurred through 40 years of age. Female official adult-onset offenders had, on average, 3 lifetime convictions each and their convictions accounted for 20% of the women’s total convictions.

Of the female Study participants, only 3% were in the official social-adulthood-onset offender subset. Official social-adulthood-onset offenders represented about one-fifth of convicted women. Female official social-adulthood-onset offenders were, on average, first convicted around 32 years of age. Female official social-adulthood-onset offenders had, on average, 3 lifetime convictions each and the convictions of this subset of adult-onset offenders accounted for 10% of the women’s total convictions.

Of the female Study members, 9% were official juvenile-onset offenders. Official juvenileonset offenders represented over half of the convicted women in the Study. Female official juvenile-onset offenders were, on average, first convicted at 17 years of age. Female official adult-onset offenders had, on average, 8 lifetime convictions each and their convictions accounted for 80% of the women’s total convictions.

The vast majority of female Study participants (85%) had not been convicted of a crime. These initial descriptive analyses (Figure 1) indicated that our main analyses should include the full official adult-onset offending group. The official social-adulthood subset was too small to study with adequate statistical power; analyses of the official social-adulthood-onset offender subset (available from the corresponding author) showed that they did not significantly differ from the full official adult-onset offender group on the remaining covariates. Likewise, these initial descriptive analyses showed that our analyses should focus on men, as comparisons among women offenders would lack adequate statistical power. Nonetheless, women appear to be somewhat different from men with regard to official adult-onset offending and we briefly return to women in the discussion. Complete analyses on women are available from the corresponding author.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of age-of-first-conviction group by sex

Does adult-onset conviction really indicate adult-onset antisocial activity?

Table 4 presents descriptive statistics and mean or proportion difference tests of unprosecuted antisocial behavior and police contact among cohort males. These data were gathered as a part of the Dunedin Study during the cohort’s childhood and adolescence. Although the official adult-onset men were first convicted during adulthood, the data suggested that most had begun their involvement in antisocial activities as children or adolescents. When all prospectively-recorded reports of juvenile antisocial behavior were compiled (last row of Table 4), 85% of the official adult-onset men had, as a juvenile, displayed evidence of notable antisocial activities. In fact, as a group, the official adult-onset men were more similar in their antisocial behavior to the official juvenile-onset men than to the official never-convicted men. On average, the official adult-onset men, compared to the official never-convicted men, had significantly more parent- and teacher-reported childhood antisocial behavior (t = 3.91, p = <.001). During adolescence, the official adult-onset men were, on average, significantly more likely than the official never-convicted men to meet diagnostic criteria for conduct disorder (t = 3.75, p = <.001) and to have self-reported crime (with the exception of self-reported crime at 15 years of age). The official adult-onset men, compared to the official never-convicted men, were also more likely to have had contact with the police during adolescence; fully 24% of the official adult-onset men already had a formal police record of arrest or police contact as a juvenile, although these arrests had not led to a criminal conviction.

Table 4.

Do male adult-onset offenders, defined on the basis of first conviction, offend prior to adulthood? Unprosecuted antisocial behavior and police contact from childhood through late adolescence as a function of age-of-first-conviction group

| Age-of-first-conviction group | Test statistics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never Convicted1 | Juvenile-onset2 | Adult-onset3 | Adult-onset vs Never convicted |

Adult-onset vs Juvenile-onset |

|||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | t | p4 | t | p4 | |

| Evidence of ASB during childhood | |||||||

| Parent and teacher reports of anti-social behavior, age 5–11 years (z-score)5 |

−0.25 (.85) | .40 (1.15) | .21 (0.95) | 3.91 | <0.001 | −1.16 | 0.124 |

| % | % | % | z | p4 | z | p4 | |

| Evidence of ASB during adolescence | |||||||

| Conduct disorder diagnosis, age 11–18 | 14.1% | 56.5% | 33.8% | 3.75 | <0.001 | −3.02 | 0.001 |

| Any self-reported offending at age 13 | 29.5% | 49.0% | 46.5% | 2.16 | 0.015 | −0.27 | 0.392 |

| Any self-reported offending at age 15 | 42.6% | 56.0% | 49.2% | 0.93 | 0.180 | −0.88 | 0.189 |

| Any self-reported offending at age 18 | 46.7% | 78.4% | 74.2% | 3.89 | < 0.001 | −0.64 | 0.260 |

| Any self-reported offending, age 13–18 | 66.1% | 88.4% | 85.9% | 3.12 | <0.001 | −0.50 | 0.310 |

| Evidence of police contact up to age 18 years | |||||||

| Parent-reported police contact, age 13–15 | 3.4% | 21.9% | 16.7% | 3.92 | <0.001 | −0.83 | 0.204 |

| Police-recorded arrest before age 18 | 9.6% | 38.4% | 24.2% | 3.23 | <0.001 | −2.00 | 0.023 |

| Any adolescent ASB or police contact | 65.4% | 92.0% | 84.9% | 3.08 | 0.001 | −1.58 | 0.057 |

Notes:

-No conviction by age 40 years, n=280.

-First conviction age 14 to 19 years, n=138.

-First conviction age 20 years and above, n=66.

-p-values are one-tailed.

-sex-standardized z-score.

Bold text indicates statistically significant difference; one-tailed p < .05.

ASB – antisocial behavior

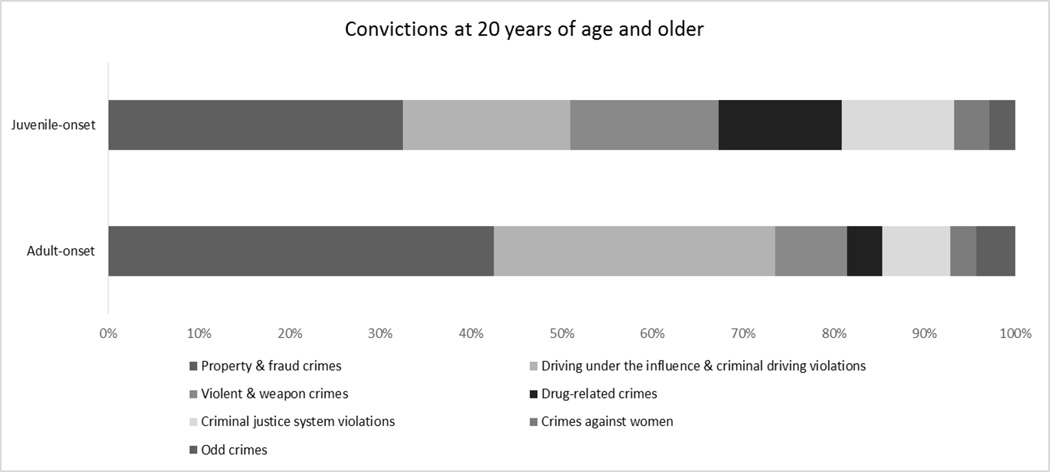

Do official adult-onset men tend to be convicted of different types of crimes compared to official juvenile-onset men?

Turning to the types of crime for which Study members were convicted, the risk ratios (Table 5) indicated that some types of crime were relatively more likely among official adult-onset men compared to official juvenile-onset men. Panel A of Table 5 shows the distribution and average rate per person of the different types of non-status offense convictions up to 40 years of age for the official juvenile-onset and the official adult-onset groups; status offenses were not possible among official adult-onset men as these men were above the age of majority at their first conviction. Panel A of Table 5 also shows the relative risk of a specific type of conviction among the official adult-onset men compared to the official juvenile-onset men, given that a conviction has occurred.

Table 5.

Are male adult-onset offenders convicted of different types of crimes compared to male juvenile-onset offenders? Comparison between juvenile- and adult-onset men on types of non-status offense crime

| Panel A: Convictions between ages 14 and 40 years as a function of age at first conviction. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conviction type | Age-of-first-conviction group | Adult-onset vs juvenile-onset risk ratio (95% CI) |

|||

| Juvenile-onset | Adult-onset | ||||

| % | Rate Per person1 |

% | Rate Per person2 |

||

| Property & fraud crimes | 41.2% | 5.31 | 42.7% | 1.80 | 1.03 (0.89–1.17) |

| Driving under the influence & criminal driving violations |

21.4% | 2.76 | 31.2% | 1.32 | 1.46 (1.20–1.72) |

| Violent & weapon crimes | 13.8% | 1.78 | 7.5% | 0.32 | 0.54 (0.35–0.82) |

| Drug-related crimes | 9.6% | 1.24 | 3.9% | 0.17 | 0.41 (0.23–0.73) |

| Criminal justice system violations | 9.3% | 1.19 | 7.5% | 0.32 | 0.81 (0.52–1.22) |

| Crimes against women | 2.3% | 0.30 | 2.9% | 0.12 | 1.24 (0.58–2.45) |

| Odd crimes | 2.4% | 0.31 | 4.3% | 0.18 | 1.81 (0.96–3.14) |

| Total | 100% | 12.90 | 100% | 4.23 | |

| Panel B: Conviction period held constant across groups. Convictions between ages 20 and 40 years as a function of age at first conviction. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conviction type | Age-of-first-conviction group | Adult-onset vs juvenile-onset risk ratio (95% CI) |

|||

| Juvenile-onset | Adult-onset | ||||

| % | Rate Per person3 |

% | Rate Per person2 |

||

| Property & fraud crimes | 32.5% | 3.56 | 42.7% | 1.80 | 1.31 (1.11–1.55) |

| Driving under the influence & criminal driving violations |

18.5% | 2.02 | 31.2% | 1.32 | 1.69 (1.36–2.11) |

| Violent & weapon crimes | 16.3% | 1.79 | 7.5% | 0.32 | 0.46 (0.30–0.71) |

| Drug-related crimes | 13.6% | 1.49 | 3.9% | 0.17 | 0.29 (0.16–0.53) |

| Criminal justice system violations | 12.3% | 1.35 | 7.5% | 0.32 | 0.61 (0.39–0.95) |

| Crimes against women | 3.9% | 0.42 | 2.9% | 0.12 | 0.74 (0.35–1.58) |

| Odd crimes | 2.9% | 0.32 | 4.3% | 0.18 | 1.48 (0.76–2.89) |

| Total | 100% | 10.96 | 100% | 4.23 | |

Notes:

-Number of observations: 124 men and 1599 convictions. Of the 138 juvenile-onset men, 14 (10%) were only ever convicted of a status offense.

-Number of observations: 66 men and 279 convictions.

-Number of observations: 85 men and 932 convictions. Of the 138 juvenile-onset men, 85 (62%) had a criminal convictions at age 20 or later.

CI-confidence interval.

Bold indicates a statistically significant different risk of conviction.

94 of the person-years (2% of the 3800 person-years in Panel A, 3% of the 3020 person-years in Panel B) were spent incarcerated.

Incarceration time did not substantively alter the results presented above and we subsequently report the more parsimonious rate of offending by person, rather than by person-year.

Among official adult-onset offenders, 30% of convictions were for driving under the influence of drugs or alcohol and other criminal driving violations; the comparable figure among official juvenile-onset offenders was 20%. A conviction for driving under the influence or a criminal driving violation was a 50% more likely type of conviction among official adult-onset men compared to official juvenile-onset men. In contrast, violent or weapon and drug crime convictions were half as likely among the official adult-onset men compared to the official juvenile-onset men. Conviction for an “odd” crime (such as offensive public behavior, peeping Tom, or an unregistered dog) was a slightly more likely type of conviction among official adult-onset men, compared to official juvenile-onset men, but not significantly so.

It is possible that the risk ratios shown in Panel A could have arisen because the official juvenile-onset group’s crime records covered more years and included the volatile adolescent period (14 to 19 years of age). Research has also shown that there may also be specific age curves for specific types of crime (Massoglia, 2006; Steffensmeier, Allan, Harer, & Streifel, 1989). To correct for this, Table 5 Panel B presents types of convictions occurring from 20 to 40 years of age for both official-onset groups, thereby holding constant across the two groups the number of years to offend and the age period of offending. Conviction-type patterns from 20 years of age onwards were similar to those for lifetime convictions. The additional finding emerged that conviction for property and fraud crime was a more likely type of conviction among the official adult-onset men than the official juvenile-onset men.

Figure 2 provides a summary of our results taking into account the exposure period (age 20–40 years). Matching the two groups on exposure produced a fairly even distribution of the type of conviction across official juvenile-onset men. In contrast, conviction types for official adult-onset men were largely concentrated as property crime and fraud, and driving-under-the-influence and other criminal driving violations. The prevalence of certain types of convictions, thus, did seem to vary between official adult-onset men and official juvenile-onset men during the same age-period. In summary, the average official adult-onset man was likely to have fewer convictions than the average official juvenile-onset man (as indicated by a lower rate per person among official adult-onset men), but the convictions were more likely to be property crime/fraud or driving crime convictions.

Figure 2.

Convictions at 20 years of age and older as a function of age-of-first-conviction group in males. The adult-onset group had proportionally more convictions for property/fraud crimes and driving under the influence/criminal driving. The adult-onset group had proportionally fewer convictions for violent/weapon crimes and drug-related crimes

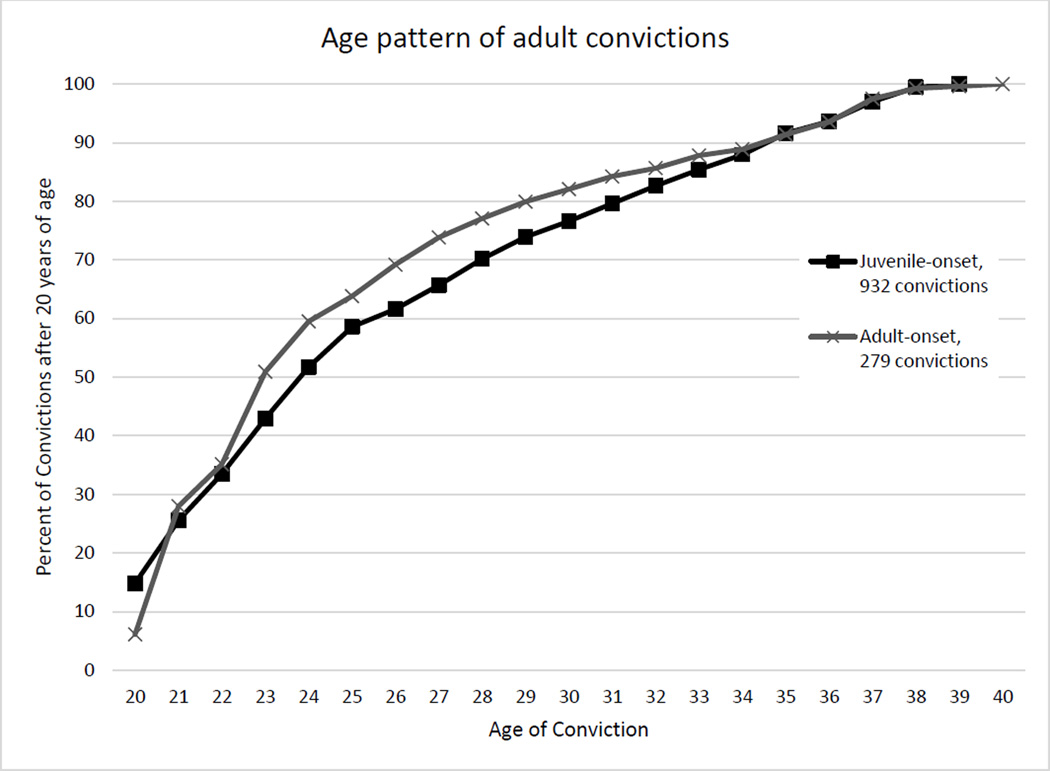

As Figure 3 shows, although official adult-onset offenders had far fewer convictions than juvenile-onset offenders, the annual percentage of convictions was similarly distributed across age between official adult-onset and official juvenile-onset men from 20 to 40 years of age. Most convictions occurred during the early 20s. From the mid-20s onwards, compared to the early 20s, fewer convictions occurred with each passing year.

Figure 3.

Annual percentage of adult convictions, cumulative distribution. The adult-onset men committed fewer crimes, but they were proportionally committed at the same age as those committed by juvenile-onset men. For both conviction groups, most convictions after age 20 years occurred during the early 20s. However, convictions steadily accumulated through age 40

Can existing theories explain adult-onset conviction?

We next tested the ten hypotheses about official adult-onset offending by comparing mean or proportion differences between official adult-onset men and official juvenile-onset men or official never-convicted men. Table 6 presents each of the hypotheses, the variable(s) that we used to test each hypothesis, whether a given variable supported the hypothesis, the data for the mean or proportion difference test, the test statistic, and the corresponding one-tailed p-value.

Table 6.

Testing ten explanations from the literature for first conviction during adulthood

| Variable | Variable supports hypothesis |

Age-of-first-conviction group | Test statistics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never convicted |

Juvenile-onset | Adult-onset | Adult-onset vs never convicted |

Adult-onset vs juvenile-onset |

||||

| t/z1 | p | t/z1 | p | |||||

| Panel A. People first convicted in adulthood evaded adolescent prosecution because… | ||||||||

| H1: Fewer offenses during adolescence reduced the likelihood of apprehension | ||||||||

| Extent of self-reported offenses, age 13 (z-score)3 | No | −0.19 (0.61) | 0.34 (1.47) | 0.11 (0.91) | 2.09 | 0.0212 | −1.11 | 0.1342 |

| Extent of self-reported offenses, age 15 (z-score)3 | Yes | −0.21 (0.69) | 0.41 (1.40) | −0.01 (0.81) | 1.96 | 0.026 | −2.64 | 0.0052 |

| Extent of self-reported offenses, age 18 (z-score)3 | Yes | −0.31 (0.63) | 0.64 (1.32) | 0.01 (0.91) | 2.56 | 0.0062 | −3.80 | <0.0012 |

| H2: Higher juvenile socioeconomic status protected them against formal sanctions | ||||||||

| Family SES, ages 1–15 (z-score)3 | No | 0.18 (1.01) | −0.29 (0.94) | − 0.18 (0.93) | −2.65 | 0.004 | 0.77 | 0.221 |

| H3: Higher intelligence facilitated evasion of detection | ||||||||

| Childhood IQ, ages 7–11 | No | 102.99 (14.88) | 97.85 (14.11) | 95.35 (15.50) | −3.72 | <0.001 | −1.14 | 0.128 |

| H4: Fewer delinquent peers during adolescence reduced visible delinquency and likelihood of detection | ||||||||

| Delinquent Peers, ages 13 & 15 (z-score)3 | Yes | −0.24 (0.64) | 0.52 (1.42) | −0.06 (0.78) | 1.73 | 0.0442 | −3.67 | <0.0012 |

| H5: Social inhibition prevented visible delinquency and likelihood of detection | ||||||||

| Social Potency, age 18 (z-score)3 | Yes | 0.00 (1.02) | 0.12 (0.98) | − 0.23 (0.92) | −1.62 | 0.053 | −2.36 | 0.010 |

| Panel B. People first convicted in adulthood begin getting prosecuted because they have… | ||||||||

| H6: More offenses during adulthood, increasing the likelihood of apprehension | ||||||||

| Extent of self-reported offenses, age 21 (z-score)3 | Yes | −0.29 (0.71) | 0.55 (1.29) | 0.13 (0.91) | 4.04 | <0.001 | −2.61 | 0.0052 |

| Extent of self-reported offenses, age 26 (z-score)3 | Yes | −0.27 (0.69) | 0.50 (1.29) | 0.15 (1.04) | 3.13 | 0.0012 | −1.88 | 0.031 |

| Extent of self-reported offenses, age 32 (z-score) 3 | Yes | −0.22 (0.69) | 0.38 (1.41) | 0.17 (0.85) | 3.48 | <0.0012 | −1.28 | 0.1012 |

| Extent of self-reported offenses, age 38 (z-score)3 | Yes | −0.23 (0.56) | 0.39 (1.34) | 0.25 (1.38) | 2.66 | 0.0052 | −0.650 | 0.26 |

| H7: Adult-onset schizophrenia or bipolar disorder | ||||||||

| Schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, age 21–38 | Yes | 1.8% | 7.8% | 9.8% | 3.18 | 0.001 | 0.48 | 0.315 |

| H8: Alcohol or substance dependence | ||||||||

| Alcohol dependence, age 21–38 | Yes | 11.4% | 25.4% | 22.7% | 2.41 | 0.008 | −0.41 | 0.341 |

| Drug dependence, age 21–38 | Yes | 5.4% | 28.3% | 12.1% | 1.98 | 0.024 | −2.56 | 0.005 |

| H9: Weak intimate-partner attachment bonds | ||||||||

| Months living with spouse or partner, age 21–38 | No | 114.95 (59.15) | 118.60 (54.94) | 101.30 (56.27) | −1.64 | 0.051 | −1.99 | 0.024 |

| Very happy with relationship, age 21 | No | 66.5% | 63.9% | 56.3% | −1.33 | 0.091 | −0.91 | 0.183 |

| Very happy with relationship, age 26 | Yes | 75.3% | 70.2% | 63.0% | −1.84 | 0.033 | −0.93 | 0.175 |

| Very happy with relationship, age 32 | No | 76.7% | 76.1% | 74.1% | −0.40 | 0.343 | −0.29 | 0.388 |

| H10: Lower expectations of informal sanctions from actors and institutions | ||||||||

| Age 21 informal sanctions from: | ||||||||

| Friends (z-score)3 | Yes | 0.28 (0.94) | −0.48 (0.97) | −0.22 (0.92) | −3.90 | <0.001 | 1.78 | 0.038 |

| Parents (z-score)3 | Yes | 0.20 (0.79) | −0.42 (1.23) | −0.02 (1.03) | −1.95 | 0.026 | 2.27 | 0.012 |

| Partner (z-score) 3 | Yes | 0.20 (0.83) | −0.38 (1.20) | −0.10 (1.00) | −2.52 | 0.006 | 1.63 | 0.052 |

| Employers (z-score)3 | No | 0.06 (0.97) | −0.08 (1.00) | −0.10 (1.10) | −1.20 | 0.116 | −0.17 | 0.432 |

| All (z-score)3 | Yes | 0.27 (0.85) | −0.48 (1.14) | −0.17 (0.89) | −3.65 | <0.001 | 2.12 | 0.0182 |

| Age 26 informal sanctions from: | ||||||||

| Friends (z-score)3 | Yes | 0.27 (0.86) | −0.41 (1.09) | −0.31 (1.00) | −4.76 | <0.001 | 0.60 | 0.273 |

| Parents (z-score)3 | Yes | 0.20 (0.77) | −0.42 (1.32) | −0.02 (0.85) | −2.07 | 0.020 | 2.51 | 0.0072 |

| Partner (z-score) 3 | No | 0.14 (0.96) | −0.29 (1.10) | −0.02 (0.81) | −1.29 | 0.099 | 1.91 | 0.0292 |

| Employers (z-score)3 | No | −0.01 (1.05) | 0.08 (0.90) | −0.13 (0.95) | −0.89 | 0.188 | 1.53 | 0.064 |

| All (z-score)3 | Yes | 0.22 (0.91) | −0.36 (1.13) | −0.18 (0.84) | 3.23 | <0.001 | 1.22 | 0.1122 |

Notes:

-Test statistic is t for difference of means, z for difference in proportions.

-Unequal variance between groups. Degrees of freedom calculated using Satterthwaite’s (1946) equation.

-sex-standardized z-score.

Bold text indicates statistically significant difference between groups; one-tailed p < .05.

Panel A of Table 6 presents results of the five hypotheses on why official adult-onset men avoided detection until adulthood, despite having engaged in antisocial activities as juveniles. In Panel A, the pertinent comparison is between the official adult-onset men and the official juvenile-onset men, shown in the shaded columns. The first hypothesis predicted that the official adult-onset men had committed fewer offenses than the official juvenile-onset men during adolescence. This was theorized to reduce their likelihood of apprehension and, subsequently, conviction. This hypothesis was generally supported. The official adult-onset men had, on average, self-reported fewer offenses at 13 years of age (t = −1.11, p = .134) and significantly fewer offenses at 15 and 18 years of age compared to the official juvenile-onset men (t = −2.64, p = .005; t = −3.80, p < .001, respectively). Thus, although Table 3 shows that most of the official adult-onset men had engaged in antisocial behaviors and delinquent offending as juveniles, their average self-reported offending was less than that of the official juvenile-onset men.

The second hypothesis argued that the official adult-onset men, compared to the official juvenile-onset men, came from families with higher socioeconomic status. Presumably a higher socioeconomic status insulated official adult-onset men from a juvenile criminal conviction. This hypothesis was not supported. The official adult-onset men had a somewhat higher average family socioeconomic status as youths than the official juvenile-onset men, but not significantly so (t = 0.77, p = .221).

The third hypothesis stated that the official adult-onset men were more intelligent than official juvenile-onset men. Higher intelligence theoretically enabled official adult-onset men to evade detection as juveniles. This hypothesis was not supported. In fact, the official adult-onset men’s average level of cognitive ability was lower than that of the official juvenile-onset men, though not significantly so (t = −1.14, p = .128).

The fourth hypothesis argued that the official adult-onset men had fewer delinquent peers than the official juvenile-onset men. Having fewer delinquent peers was presumed to reduce the extent and diversity of offending, and likelihood of apprehension. This hypothesis was supported. Official adult-onset men had, on average, significantly fewer delinquent friends than official juvenile-onset men (z = −3.67, p < .001).

The fifth hypothesis stated that the official adult-onset men, compared to the official juvenile-onset men, were more socially inhibited. It was theorized that social inhibition excluded official adult-onset men from group offending, reducing the likelihood of apprehension and conviction. This personal construct of timidity was measured by low scores on a scale of “social potency.” This hypothesis was supported. The official adult-onset men’s average social potency score was significantly lower than that of the official juvenile-onset men’s average score (t = −2.36, p = .010).

Panel B of Table 6 presents results for five additional hypotheses, about why the official adult-onset men first began getting convicted during adulthood. The relevant comparison in this panel is between the official adult-onset men and the official never-convicted men, shown in the shaded columns.

The sixth hypothesis stated that the official adult-onset men committed more offenses than the official never-convicted men during adulthood. This was theorized to increase their likelihood of apprehension and, subsequently, conviction. This hypothesis was generally supported. The official adult-onset men, compared to the official never-convicted men, had, on average, self-reported more offenses at 21, 26, 32, and 38 years of age (t = 4.04, p <. 001; t = 3.13, p = .001; t = 3.48, p < .001; t = 2.66, p = .005, respectively).