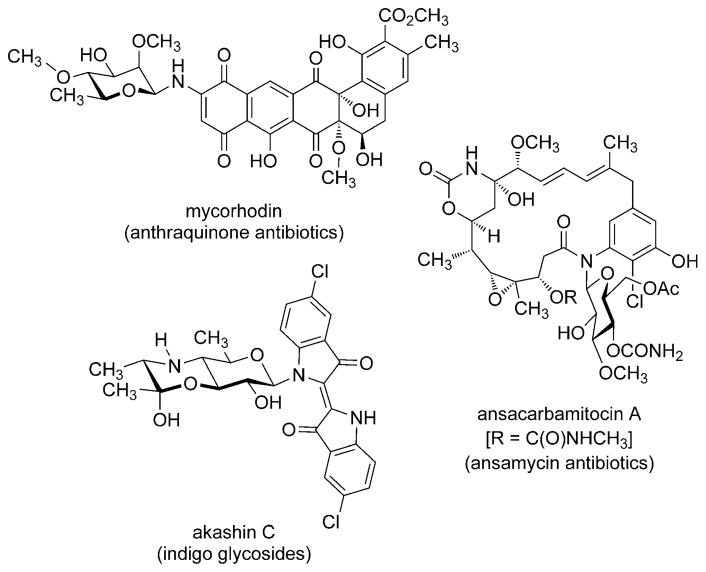

The β-N-glycoside linkage is embedded within structurally diverse natural products such as the anthraquinone antibiotics (e.g. mycorhodin),[1] indigo glycosides (e.g. akashin C),[2] and the ansamycin antibiotics (e.g. ansacarbamitocin A; Scheme 1).[3, 4] This linkage is also found in a large number of glycopeptides, which exhibit a broad spectrum of biological functions;[5] erythropoietin (EPO) is a well-known example.

Scheme 1.

Representative natural products that contain the β-N-glycoside linkage.

Reported methods for the synthesis of N-linked glycoside bonds include the functionalization of glycosyl azides[6] and the condensation of ammonia,[7,8] N,O-dialkylhydroxylamines,[9] and acyl hydrazides[10] with reducing sugars. We describe herein a simple and complementary method that proceeds by mild thermolysis of alkyl and aryl azides in the presence of reducing sugars and a tertiary phosphine; it is essentially an aza-Wittig reaction in which a carbohydrate is used as a latent carbonyl group [Eq. (1)]. Despite the simplicity of this approach, to our knowledge, a single report describing the condensation of a polyfluorinated iminophosphorane and lactose[11] stands as the only direct precedent for this reaction.

|

(1) |

The condensation of ammonia and N,O-dialkyl hydroxyl-amines with unactivated carbohydrates is well-developed, and this method has found great utility in the synthesis of glycoproteins[12] and natural product glycoconjugate libraries.[9a–c] However, the reaction of ammonia with a reducing sugar requires long reaction times and a large excess of ammonia to drive the process to completion, thus rendering this process unsuitable for the synthesis of N-glycosides incorporating precious amine fragments. The condensation of N,O-dialkyl hydroxylamines with carbohydrates is more efficient, but necessarily provides an unnatural (neoglycoside) linkage. The method we report herein is characterized by short reaction times, a small (0.5 equiv) excess of reagent, and high selectivity for the β-N-glycoside product.

The reaction between an azide, phosphine, and carbohydrate to form an N-glycoside and phosphine oxide may proceed by several pathways. Regardless, the overall transformation is formally a Staudinger reduction–aza-Wittig sequence and we therefore began by evaluating the ability of various phosphines to promote the coupling of benzyl azide (1a) and O-allyl-N,N-dimethyl-D-pyrrolosamine (2a, Table 1).[13] Products derived from the protected 2,6-dideoxy-glycoside 2a can be readily purified by flash-column chromatography, and exhibit well-resolved resonances in their 1H NMR spectra, which facilitated the characterization of the products and optimization of the reaction conditions. Heating a mixture of 1a (1.5 equiv) and 2a in the presence of triphenylphosphine (1.5 equiv) in tetrahydrofuran as the solvent resulted in the formation of the N-glycoside 3a in 24% yield and with a > 15:1 selectivity for the β anomer (1H NMR spectroscopic analysis; JH1-H2ax = 10.5 Hz). The reaction did not proceed at lower temperatures (24 °C). When the more reactive dimethylphenylphosphine was employed, the product 3a was isolated in 56 % yield (entry 2). Reasoning that protic acids might promote the pyranose–hydroxyaldehyde isomerization, a variety of acidic additives were evaluated. The addition of para-toluenesulfonic acid (5 mol %) increased the yield of the N-glycoside 3a to 90 % (entry 3). Trimethylphosphine was also effective as the reductant (88 % yield, entry 4). The product was obtained in lower yield when N,N-dimethylformamide was employed as the solvent (43 %, entry 5).

Table 1.

Optimization of the reductive glycosylation.[a]

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Phosphine | Additive | Solvent | Yield [%] (β/α)[b] |

| 1 | PPh3 | – | THF | 24 (> 15 :1) |

| 2 | P(CH3)2Ph | – | THF | 56 (> 15 :1) |

| 3 | P(CH3)2Ph | PTSA (5 mol %) | THF | 90 (> 15 :1) |

| 4 | P(CH3)3 | PTSA (5 mol %) | THF | 88 (> 15 :1) |

| 5 | P(CH3)2Ph | PTSA (5 mol %) | DMF | 43 (> 15 :1) |

Conditions : Benzyl azide (1 a, 1.50 equiv), 2 a (1 equiv), phosphine (1.50 equiv), 55 °C, 12 h.

Yield of isolated product after purification by flash-column chromatography.

THF = tetrahydrofuran, PTSA = p-toluenesulfonic acid, DMF = N,N-dimethylformamide, PMB = para-methoxybenzyl, CBz = benzyloxycarbonyl.

This reductive N-glycosylation reaction has proven to be relatively general in nature (Table 2). As shown in entries 1–4, primary alkyl azides coupled with 2a in high yields (72–90 %). Phenyl azide (1e) also formed the corresponding N-phenyl-N-glycoside 3 e in 83 % yield (entry 5), thus establishing that this method is not limited to alkyl azide substrates. Ethyl azidoacetate (1 f) and ω-azidolysine methyl ester (1g) both coupled with 2a in high yields (77 and 78%, entries 6 and 7, respectively). Benzyl azide (1a) also coupled efficiently with O-allyl-L-oleandrose (2b, 88%; entry 8). 2,3,5-Tribenzyl-D-ribose (2c) underwent conjugation with para-methoxybenzyl azide (1b) in 73% yield (entry 9). N-Acetyl- D -glucosamine (2d) and the fully deprotected carbohydrates D-glucose (2 e) and maltose (2 f) were shown to couple with benzyl and phenyl azide in yields of 72–82% (entries 10–13). The product 3i, derived from ribose (entry 9), was formed with a β :α selectivity of 3:2; in all other cases, the β anomer was obtained with > 15:1 selectivity (1H NMR spectroscopic analysis).

Table 2.

Scope of the reductive glycosylation reaction.[a]

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Azide | Carbohydrate donor | Yield [%][b] |

| 1 | BnN3 1 a | 90 3 a | |

| 2 | PMBN3 1 b | 72 3 b | |

| 3 |

1 c |

78 3 c | |

| 4 |

1 d |

2 a |

84 3 d |

| 5 | PhN3 1 e | 83 3 e | |

| 6 |

1 f |

77 3 f | |

| 7 |

1 g |

78 3 g | |

| 8 | BnN3 1 a |

2 b |

88 3 h |

| 9 | PMBN3 1 b |

2 c |

73 3 i 3 :2 β :α |

| 10[c] | BnN3 1 a |

2 d |

76 3 j |

| 11[c] | BnN3 1 a |

2 e |

82 3 k |

| 12[c] | PhN3 1 e | 78 3 l | |

| 13[c] | BnN3 1 a |

2 f |

72 3 m |

Conditions : Azide (1 equiv), PhP(CH3)2 (1.00 equiv), carbohydrate (1.50 equiv), PTSA (5 mol %), THF, 55 °C, 12 h. All reactions were conducted on a 0.5 mmol scale.

Yield of isolated product after purification by flash-column chromatography. β :α selectivity > 15 :1, unless otherwise noted.

Reaction conducted with 1 equiv carbohydrate, 1.50 equiv azide, and 1.50 equiv PhP(CH3)2, THF, 55 °C, 12 h.

PMB = p-methoxybenzyl ; CBz = benzyloxycarbonyl.

The results in Table 2 demonstrate that β-linked N-glycosides are readily formed from simple azides and reducing sugars. It was of interest to determine if the method is also amenable to the synthesis of N-linked glycopeptides and, in particular, to the formation of the β-Asn-N-acetylglucosamine linkage, which is abundant in natural glycoproteins.[5] Toward this end, we envisioned a sequence comprising the N-glycosylation of an ammonia equivalent, followed by aspartylation.[12, 14] After much experimentation, we found that heating trimethylsilylmethyl azide (1h)[15] and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (2d) with dimethylphenylphosphine resulted in the formation of the β-linked N-glycoside 3 n in 75 % yield as a 30:1 mixture of β and α anomers (Scheme 2). Benzoylation of 3n (benzoyl chloride) afforded the benzamide 4a in 85% yield. Finally, the trimethylsilylmethyl substituent was cleaved by treatment with ceric ammonium nitrate in acetonitrile (90%).[16] The benzamide 5a was obtained without detectable erosion of the anomeric site (1H NMR spectroscopic analysis). This sequence provides a complementary and highly practical alternative to the reaction of carbohydrates with ammonia, as primary N-glycosides are notoriously difficult to purify and are prone to epimerization at the anomeric position.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of the N-benzoyl-N-glycoside 5 a. TMS = trimethylsilyl, Bz = benzoyl, THF = tetrahydrofuran, CAN = ceric ammonium nitrate.

This approach was readily adapted toward amino acid coupling reactions by employing the corresponding amino acid mixed anhydride in the acylation step. A selection of glycosylated amino acids and peptides prepared in this way are shown in Table 3. As a consequence of their high polarities, the intermediates in these sequences were employed without purification, although they may be isolated by reverse-phase chromatography, if desired. This approach led to the anomerically pure glucosamine derivatives 5b and 5c in high overall yields (76 % and 75% for 5b and 5c, respectively). The Asn-linked tripeptide was also obtained in excellent yield and with complete β selectivity (5d, 70 %). Finally, we discovered that the method is amenable to the direct introduction of disaccharides (5e, 61 %), which suggests its application in more complex settings.

Table 3.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Entry | Product | Yield [%][b] |

| 1 |

5b |

76 |

| 2 |

5c |

75 |

| 3 |

5d |

70 |

| 4 |

5e |

61 |

Conditions : Step 1: 1 h (1.50 equiv), PhP(CH3)2 (1.50 equiv), 2 d or 2 f (1 equiv), THF, 55 °C. Step 2 : ClCO2iBu (1.20 equiv), amino acid (1.10 equiv), TEA (1.20 equiv), THF, −40 →24 °C. Step 3 : CAN (5.00 equiv), CH3CN/H2O (30 :1, v/v), MW, 90 °C, 10 min.

Yield of isolated product after purification by flash-column chromatography. β :α selectivity > 15 :1.

TEA = triethylamine, MW = microwave, Bn = benzyl, Fmoc = 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl.

Although glycosyl azides have been widely used for the synthesis of N-glycosides,[6] the reductive condensation of azides with unactivated sugars does not appear to have been developed. We have disclosed herein a simple and straightforward method for the stereocontrolled synthesis of β-linked N-glycosides by employing alkyl and aryl azides as the sources of nitrogen atoms. The method is compatible with protected and deprotected carbohydrate donors, and does not require activation of the anomeric position. A simple, high-yielding procedure for the synthesis of β-Asn-linked glycosides has been developed, and this method may be of great utility in the synthesis of complex glycopeptides. Efforts to fully delineate the scope of the azide and carbohydrate components, as well as applications in natural products synthesis, are underway.

Experimental Section

Representative experimental procedure (Table 2, entry 1): Benzyl azide (1a; 67.0 mg, 500 μmol, 1 equiv) and THF (300 μL) were added in sequence to an oven-dried 4 mL vial equipped with a teflon-lined cap and magnetic stir bar. Dimethylphenylphosphine (70.0 mg, 500 μmol, 1.00 equiv) was added dropwise by syringe over 5 min. The reaction vessel was sealed under an atmosphere of argon and the mixture stirred for 30 min at 24°C. A solution of 2a (161 mg, 750 μmol, 1.50 equiv) in THF (100 μL) and para-toluenesulfonic acid (5.0 mg, 25.0 μmol, 0.05 equiv) were then added in sequence. The vial was sealed under argon and then placed in an oil bath that had been preheated to 55°C. The reaction mixture was stirred and heated for 12 h at 55°C before cooling the product mixture to 23°C. The cooled product mixture was concentrated to dryness and the residue obtained was purified by flash-column chromatography (deactivated with 1% triethylamine/5 % acetone in hexanes; eluting with 5% acetone in hexanes) to provide the N-glycoside 3a as a clear, colorless oil (two runs: 139 mg and 133 mg, average yield = 90%).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Financial support from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01GM090000), the Searle Scholars Program, Shanghai Committee of Science and Technology (11DZ2260600, Shanghai Municipal Education Commission Fellowship to J.Z.), and Yale University is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Dr. Seann Mulcahy for preliminary experiments and Dr. Le Li for helpful discussions.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http ://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201301264.

Contributor Information

Dr. Jianbin Zheng, Department of Chemistry, Yale University, 225 Prospect Street, New Haven, CT 06520-8107 (USA). Shanghai Key Laboratory of New Drug Design, School of Pharmacy, East China University of Science and Technology (P.R. China)

Dr. Kaveri Balan Urkalan, Department of Chemistry, Yale University, 225 Prospect Street, New Haven, CT 06520-8107 (USA)

Dr. Seth B. Herzon, Email: seth.herzon@yale.edu, Department of Chemistry, Yale University, 225 Prospect Street, New Haven, CT 06520-8107 (USA). Homepage : http://www.chem.yale.edu/faculty/herzon.html

References

- 1.a) Takeda U, Okada T, Takagi M, Gomi S, Itoh J, Sezaki M, Ito M, Miyadoh S, Shomura T. J Antibiot. 1988;41:417. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.41.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Takeda U, Okada T, Takagi M, Gomi S, Itoh J, Sezaki M, Ito M, Miyadoh S, Shomura T. J Antibiot. 1988;41:425. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.41.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Maskey RP, Grün-Wollny I, Fiebig HH, Laatsch H. Angew Chem. 2002;114:623. [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 597; b) Maskey RP, Grün-Wollny I, Laatsch H. Nat Prod Res. 2005;19:137. doi: 10.1080/14786410410001704741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snipes CE, Duebelbeis DO, Olson M, Hahn DR, Dent WH, Gilbert JR, Werk TL, Davis GE, Lee-Lu R, Graupner PR. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:1578. doi: 10.1021/np070275t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.For additional examples, see Omura S, Iwai Y, Hirano A, Nakagawa A, Awaya J, Tsuchiya H, Takahashi Y, Masuma R. J Antibiot. 1977;30:275. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.30.275.Nettleton DE, Doyle TW, Krishnan B, Matsumoto GK, Clardy J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:4011.Bonjouklian R, Smitka TA, Doolin LE, Molloy RM, Debono M, Shaffer SA, Moore RE, Stewart JB, Patterson GML. Tetrahedron. 1991;47:7739.Matsunaga S, Fusetani N, Kato Y, Hirota H. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:9690.

- 5.For selected reviews, see Spiro RG. Glycobiology. 2002;12:43R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/12.4.43r.Gamblin DP, Scanlan EM, Davis BG. Chem Rev. 2009;109:131. doi: 10.1021/cr078291i.Kan C, Danishefsky SJ. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:9047. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2009.09.032.Larkin A, Imperiali B. Biochemistry. 2011;50:4411. doi: 10.1021/bi200346n.

- 6.For selected examples, see Mizuno M, Muramoto I, Kobayashi K, Yaginuma H, Inazu T. Synthesis. 1999:162.He Y, Hinklin RJ, Chang J, Kiessling LL. Org Lett. 2004;6:4479. doi: 10.1021/ol048271s.Doores KJ, Mimura Y, Dwek RA, Rudd PM, Elliott T, Davis BG. Chem Commun. 2006:1401. doi: 10.1039/b515472c.for a recent review, see Györgydeák Z, Thiem J. Adv Carbohydr Chem Biochem. 2006;60:103. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2318(06)60004-8.

- 7.a) Likhosherstov LM, Novikova OS, Derevitskaja VA, Kochetkov NK. Carbohydr Res. 1986;146:C1. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(90)84093-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Urge L, Kollat E, Hollosi M, Laczko I, Wroblewski K, Thurin J, Otvos L., Jr Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:3445. [Google Scholar]

- 8.The condensation of allyl- and benzylamine (10 equiv, 4 days reaction time) with unactivated carbohydrates has been reported: Cipolla L, Lay L, Nicotra F, Pangrazio C, Panza L. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:4679.

- 9.a) Langenhan JM, Peters NR, Guzei IA, Hoffmann FM, Thorson JS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503270102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ahmed A, Peters NR, Fitzgerald MK, Watson JA, Jr, Hoffmann FM, Thorson JS. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14224. doi: 10.1021/ja064686s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Peltier-Pain P, Timmons SC, Grandemange A, Benoit E, Thorson JS. ChemMedChem. 2011;6:1347. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201100178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; for reviews, see d) Griffith BR, Langenhan JM, Thorson JS. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2005;16:622. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Langenhan JM, Griffith BR, Thorson JS. J Nat Prod. 2005;68:1696. doi: 10.1021/np0502084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peluso Sp, Imperiali B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:2085. [Google Scholar]

- 11.El Ghoul M, Escoula B, Rico I, Lattes A. J Fluorine Chem. 1992;59:107. [Google Scholar]

- 12.For selected examples, see Wang P, Zhu J, Yuan Y, Danishefsky SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:16669. doi: 10.1021/ja907136d.Nagorny P, Sane N, Fasching B, Aussedat B, Danishefsky SJ. Angew Chem. 2012;124:999. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107482.Wang P, Li X, Zhu J, Chen J, Yuan Y, Wu X, Danishefsky SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:1597. doi: 10.1021/ja110115a.

- 13.Gholap SL, Woo CM, Ravikumar PC, Herzon SB. Org Lett. 2009;11:4322. doi: 10.1021/ol901710b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anisfeld ST, Lansbury PT. J Org Chem. 1990;55:5560. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishiyama K, Tanaka N. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1983:1322. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palomo C, Aizpurua JM, Legido M, Mielgo A, Galarza R. Chem Eur J. 1997;3:1432. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.