Abstract

Objective

Adipose tissue (AT)-specific inflammation is considered to mediate the pathological consequences of obesity and macrophages are known to activate inflammatory pathways in obese AT. Because cyclooxygenases play a central role in regulating the inflammatory processes, we sought to determine the role of hematopoietic cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) in modulating AT inflammation in obesity.

Materials/Methods

Bone marrow transplantation was performed to delete COX-1 in hematopoietic cells. Briefly, female wild type (wt) mice were lethally irradiated and injected with bone marrow (BM) cells collected from wild type (COX-1+/+) or COX-1 knock-out (COX-1−/−) donor mice. The mice were fed a high fat diet for 16 wk.

Results

The mice that received COX-1−/− bone marrow (BM-COX-1−/−) exhibited a significant increase in fasting glucose, total cholesterol and triglycerides in the circulation compared to control (BM-COX-1+/+) mice. Markers of AT-inflammation were increased and were associated with increased leptin and decreased adiponectin in plasma. Hepatic inflammation was reduced with a concomitant reduction in TXB2 levels. The hepatic mRNA expression of genes involved in lipogenesis and lipid transport were increased while expression of genes involved in regulating hepatic glucose output were reduced in BM-COX-1−/− mice. Finally, renal inflammation and markers of renal glucose release were increased in BM-COX-1−/− mice.

Conclusion

Hematopoietic COX-1 deletion results in impairments in metabolic homeostasis which may be partly due to increased AT inflammation and dysregulated adipokine profile. An increase in renal glucose release and hepatic lipogenesis/lipid transport may also play a role, at least in part, in mediating hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia, respectively.

Keywords: obesity, dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, eicosanoids

Introduction

Adipose tissue (AT) dysfunction characterized by macrophage accumulation and inflammation is considered to play an important role in mediating obesity-linked metabolic disorders, including insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hepatic steatosis [1–3]. The mechanism by which macrophages are recruited to AT and modulate AT inflammation in obesity is still an area of intense research. The role of certain genes in modulating inflammatory pathways, including monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), CC chemokine receptor-2 (CCR2), CCR5 and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), has been studied by various groups. Mice with global deficiency of MCP-1 showed reduced AT macrophage content [4]. Deletion of the chemokine receptor CCR5 in bone marrow stem cells has been shown to reduce AT macrophage accumulation and the inflammatory response [5]. In addition, hematopoietic cell-specific deletion of TLR4 reduced AT macrophage content and inflammatory markers [6]. Overall, inhibition of inflammatory pathways appears to be effective in reducing AT macrophage accumulation and/or inflammation in obesity.

As for the immunomodulatory pathways, cyclooxygenases (COX), which exist in two forms, COX-1 and −2, play an important role in regulating the inflammatory response in several cell types, including macrophages. In fact, all the currently available non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs act via inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX) activity. Both isoforms of COX can produce similar prostaglandin (PG) and thromboxane (TX) metabolites from arachidonic acid, but COX-1 is constitutively expressed, whereas COX-2 is expressed mainly under pathological states [7]. While a number of immunomodulatory genes involved in altering metabolic inflammation associated with obesity have been studied, the effects of COX-1 in altering AT inflammation and the systemic metabolic profile (i.e. circulating glucose, triglyceride and cholesterol levels) in obesity are unclear. As for the role of COX-2, global deficiency of this isoform of COX has been shown to reduce AT-inflammation in mice [8]. In addition, pharmacological inhibition of COX-2 can also reduce AT inflammation in obesity [9]. However, the role of COX-1 in modulating AT inflammation in obesity still remains unknown.

Macrophages are an important source of both COX-1 and −2 [10, 11], and each plays a role in the regulation of the inflammatory response. Although COX-derived eicosanoids are generally considered to be pro-inflammatory, some of them, in particular PGE2, PGI2 and PGD2 play a role in the resolution of inflammation [12–14]. While COX-1 and −2 produce both types of eicosanoids (TXs and PGs) from arachidonic acid, COX-1 is constitutively expressed and is considered to be a major source of these eicosanoids in [15–17]. Of note, TXs are known to mediate an inflammatory response in various organs [18, 19]. In particular, a balance between TXs and prostacyclin (PGI2) is considered to regulate inflammation. It has been reported in both human and animal models of the metabolic syndrome that there is an elevated TXA2 to PGI2 ratio in urine and blood plasma [20, 21]. In addition, obese women had significantly higher excretion of 11-dehyro TXB2 in urine [22]. Interestingly, improved insulin sensitivity with pioglitazone treatment in these subjects was associated with decreased urinary 11-dehydro TXB2 excretion. Therefore, we hypothesized that deletion of COX-1 in macrophages would reduce AT macrophage accumulation and the inflammatory response in obesity.

To test this hypothesis, we conducted bone marrow transplantation using wild type (wt) mice as recipients and wt or COX-1 global knock-out mice as donors. This approach has been widely employed to determine the role of hematopoietic cells, in particular macrophages, in modulating obesity-associated inflammation and metabolic disorders [23–25].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and diet

COX-1 deficient mice (COX-1−/−) [26] were kindly provided by Dr. Chuan-Ming Hao at Vanderbilt University. These mice were crossed onto a C57BL/6 (Jackson Laboratories) background more than 12 times and fed a high fat diet containing 45% fat by energy for a period of 16 wk. The diet contained the required vitamins and minerals and a fat mixture at 209 g/kg, which was derived from 45% coconut oil, 36% olive oil, 15% corn oil, and 10% soy bean oil, as described previously [27, 28], except that the diet used in the current study did not have added cholesterol. All animal care procedures were carried out with approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Vanderbilt University.

Bone marrow transplantation (BMT)

We performed BMT to study the specific role of hematopoietic COX-1 in modulating AT macrophage accumulation and AT inflammation in obesity. Briefly, wt (COX-1+/+) and COX-1−/− donor mice were killed by cervical dislocation under anesthesia and bone marrow was collected from the femurs and tibias. Wt mice purchased from Jackson Laboratories were used as the recipients for both types of donor marrow [6, 29]. For each donor genotype (COX-1+/+ and COX-1−/−) bone marrow was pooled and ∼2–5 × 106 bone marrow cells were injected into lethally irradiated wt recipient mice via the retroorbital venous plexus. The recipient mice were given antibiotic water (5 mg of neomycin and 25,000 U polymyxin B sulfate/l) for 1 wk prior to and 2 wk following BMT. The control wt recipients that received wt COX-1+/+ bone marrow cells will be referred to as BM-COX-1+/+ and the wt recipients that received the COX-1−/− marrow will be denoted as BM-COX-1−/− mice. DNA was extracted from spleen tissue from the recipient mice in each bone marrow transplant group. PCR for the COX-1−/− genotype was performed to confirm reconstitution of the mutant gene with hematopoietic cells as described previously [30, 31].

Body composition and food intake

Total fat mass was measured by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy using a Bruker Minispec (Woodlands, TX, USA) in the Vanderbilt Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center (MMPC) at 16 wk on the high fat diet. The food intake was measured twice weekly over the 16 wk period.

Plasma metabolic variables

After 16 wk on the experimental diet, the mice were bled via the retroorbital plexus following 5 h of fasting. Glucose was measured using the Accu-chek Aviva glucometer. Plasma insulin measurements were performed using an insulin assay kit (Mercodia). The homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was used as a measure of insulin resistance and was calculated using the following equation: HOMA-IR = fasting serum insulin (µU/mL) × fasting serum glucose (mg/dL)/405. Plasma total cholesterol and triglycerides were measured using kits from Raichem. Plasma leptin levels were measured using a leptin assay kit (Millipore) and adiponectin levels were determined by western blot analysis.

Measurement of COX-1 activity in whole blood and eicosanoids in tissues

To determine whether COX-1 activity was lower in BM-COX-1−/− compared to BM-COX-1+/+ mice, thromboxane B2 (TXB2) levels were measured in whole blood as we described previously [32] . At sacrifice, 200 µl of blood collected in heparin (19 units/ml) was stimulated with ionomycin (50 µM) for 30 min at 37°C and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. Plasma was frozen at −80°C immediately thereafter. TXB2 levels were determined using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) at the Eicosanoid Core Laboratory at Vanderbilt University. We also determined the tissue levels of TXB2, 6-keto PGF1α (a stable metabolite of PGI2), and PGE2 in liver and kidney samples using this method.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from liver and perigonadal AT using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and cDNA synthesis was carried out using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit from Bio-Rad. Real-time PCR analysis was performed for macrophage and inflammatory markers as well as genes involved in glucose and lipid metabolism using applied on-demand primer-probes from Applied Biosystems. The AACT method was used to quantify mRNA expression levels.

Western blot analysis

Tissue homogenates were collected from liver, soleus muscle, perigonadal AT and kidney samples. Western blot analysis was performed to determine the levels or phosphorylation status of proteins regulating glucose homeostasis. The antibodies for phosphoenol pyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK), glucose-6-phosphatase (G6PC), glucose transporter-4 (Glut-4), and phospho insulin receptor beta (IR-β) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. Anti-adiponectin antibody was from Abcam. The antibodies for glyceraldehyde 3 phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and total and phosphorylated AKT and glycogen synthase kinase (GSK) were from Cell Signaling Tech. IRDye 680 (red) and 800 (green) conjugated secondary antibodies were obtained from LI-COR Biosciences. The blots were scanned using the Odyssey system (LI-COR).

Immunofluorescence

Immunohistochemical studies were performed on slides from paraffin-embedded tissues. Following incubation with primary antibodies, the sections were washed and incubated with Alexa Fluor 568 conjugated secondary antibodies. The sections were mounted with antifade gold containing DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, Invitrogen). The antibodies for mouse homologue of EGF-like module-containing mucin-like hormone receptor-like 1 (F4/80), MCP-1, and SGLT-2 were purchased from Santacruz Biotechnology Inc. Anti-macrophage galactose type lectin (MGL) was obtained from Abcam. The pictures were taken using Nikon eclipse 80i inverted fluorescence microscope. Immunofluorescence analysis was performed in at least 3 samples from each group and a representative picture from each group is shown.

Isolation of stromal vascular cells (SVCs)

Perigonadal AT pads were minced in 0.1% BSA in PBS and spun at 1200 rpm to remove the red blood cells. The supernatant with minced fat was transferred to a 50 mL conical tube and collagenase at 1mg/mL was added and incubated at 37°C for 1 h with shaking. The cell suspension was filtered through a 100 µm nylon filter. The filtrate was spun to remove the floating adipocytes from the SVCs.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as the mean ± SEM. Data were analyzed with Prism GraphPad using the Student’s ‘t’ test to determine statistical significance (P<0.05 was considered significant).

RESULTS

Effects of COX-1 deletion in hematopoietic cells on metabolic parameters in mice challenged with a high fat diet

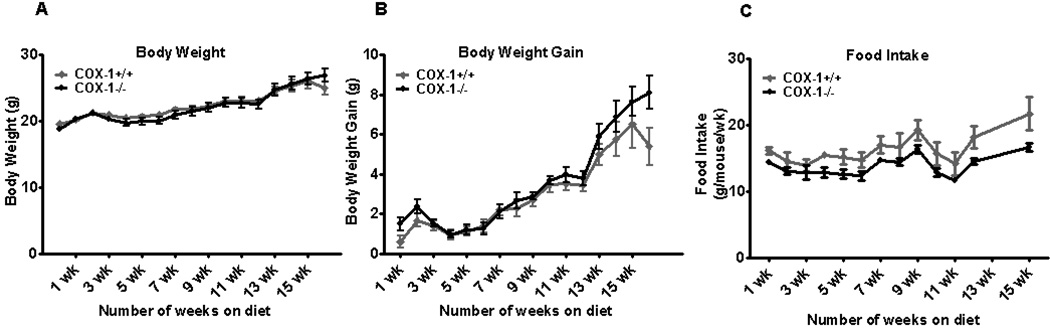

Although BMT renders the mice less susceptible to gaining weight, total body weight was significantly increased in both groups of mice compared to their respective baseline values (19.6 ± 0.3 vs 25.0 ± 1.0, P<0.001, and 18.8 ± 0.4 vs 26.9± 1.0, P<0.0001 in BM-COX-1+/+ and BM-COX-1−/− groups, respectively). As shown in Table 1, at the end of 16 wk on a high fat diet, BM-COX-1−/− mice exhibited a marginally significant (P<0.051) increase in body weight gain compared to the BM-COX-1+/+ control mice. Total fat mass analyzed by NMR spectrometry was not altered significantly in BM-COX-1−/− mice whereas there was a marginally significant (P<0.051) increase in perigonadal AT mass and a significantly greater perigonadal AT mass normalized to body weight at the time of sacrifice. Liver weight and cumulative food intake did not differ in BM-COX-1−/− mice. Likewise, weekly body weight and body weight gain were not significantly altered between the two groups over the 16 wk period (Figure 1 A&B). We also noted that the weekly food intake tended to be slightly lower in BM-COX-1−/− compared to BM-COX-1+/+ mice throughout the feeding period (Figure 1C).

Table 1.

Effect of hematopoietic COX-1 on metabolic parameters in mice after 16 wk on a high fat diet

| Measurements | COX-1+/+ | COX-/1−/− |

|---|---|---|

| n | 7 | 8 |

| Body weight (g) | 25.0 ± 1.0 | 26.9 ± 1.0 |

| Body weight gain (g) | 5.39 ± 0.95 | 8.11 ± 0.85 |

| Fat mass (g) | 4.89 ± 1.2 | 6.35 ± 0.66 |

| Fat mass/body weight | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 0.23 ± 0.02 |

| Perigonadal AT mass (g) | 0.67 ± 0.14 | 1.06 ± 0.11 |

| Perigonadal AT mass/body weight | 0.026 ± 0.005 | 0.039 ± 0.003* |

| Liver weight (g) | 1.21 ± 0.05 | 1.03 ± 0.08 |

| Cumulative Food Intake (g) (g/mouse/wk) |

16.5 ± 1.2 | 14.1 ± 0.2 |

P<0.05 vs. the COX-1+/+ controls. Values are mean ± SEM of 7–8 samples per group for all the measurements except food intake. Food intake was measured in 2 cages of mice per group (n=2).

Figure 1.

Effect of hematopoietic COX-1 on body weight and food intake in mice. Lethally irradiated wild type recipient mice were reconstituted with COX-1−/− bone marrow and placed on a high fat diet starting 4 wk post-BMT and sacrificed 16 wk after the diet feeding. Weekly body weight (A) and body weight gain (B) in mice were recorded. Values are mean ± SEM of 7–8 mice in each group. The food intake (C) was measured in 2 cages of mice per group (n=2).

Effects of COX-1 deletion in hematopoietic cells on TXB2 formation in blood cells of mice challenged with a high fat diet

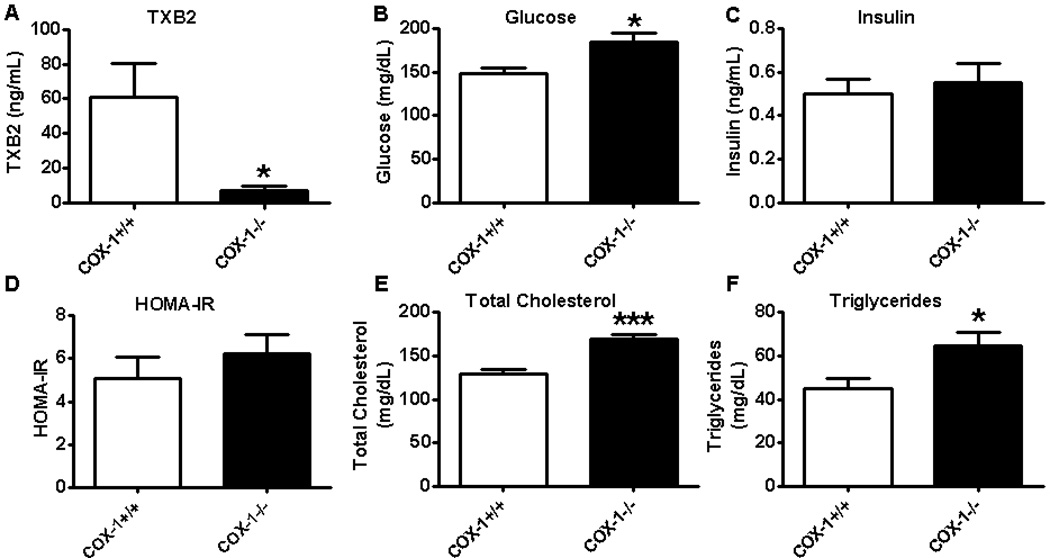

Using an ex vivo method, which is widely used to determine COX-1 activity in whole blood [33–35], we observed a profound decrease in TX formation in BM-COX-1−/− mice compared to control (Figure 2A). The small amount of TXB2 seen in BM-COX-1−/− mice may have been due to COX-2 activity.

Figure 2.

Impact of COX-1 deletion in hematopoietic cells on COX-1 activity and other metabolic variables in mice. The whole blood samples collected from these mice were processed as described in Methods to analyze TXB2 levels (A), a measure of COX-1 activity. Blood glucose (B) and plasma insulin (C), HOMA-IR (D), total cholesterol (E), and triglycerides (F) were analyzed. Values are mean ± SEM of 6–8 mice in each group. *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001 vs COX-1+/+ control.

Effects of COX-1 deletion in hematopoietic cells on the systemic metabolic profile in mice challenged with a high fat diet

The fasting blood glucose level was significantly increased in BM-COX-1−/− compared to BM-COX-1+/+ control mice. Plasma insulin and HOMA-IR, a measure of systemic insulin resistance, were not different however. Plasma total cholesterol and triglycerides were increased in mice lacking COX-1 in hematopoietic cells compared to their control (Figure 2 B–F). Together, these data show that hematopoietic deletion of COX-1 results in hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia, features of metabolic syndrome.

Effects of COX-1 deletion in hematopoietic cells on AT macrophage accumulation and AT inflammation in mice challenged with a high fat diet

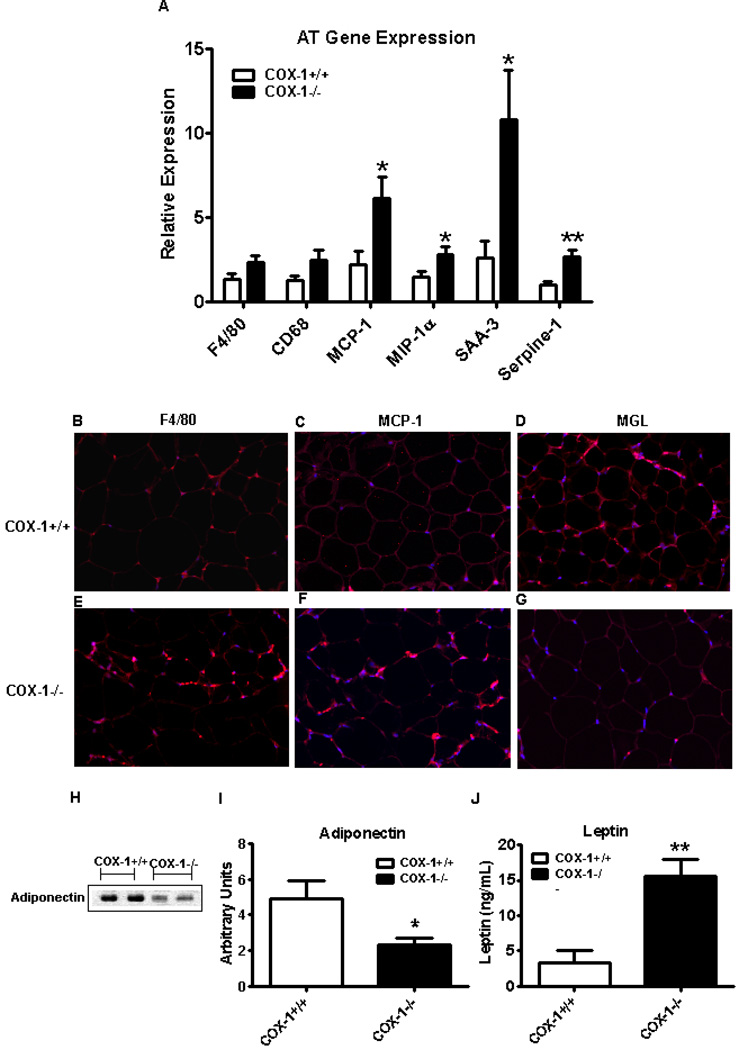

Because obesity-associated metabolic disorders are thought to be mediated through accumulation of AT macrophages and AT-specific inflammation [23, 36], we next wanted to determine the role of hematopoietic COX-1 in modulating AT macrophage accumulation and inflammation. We performed realtime PCR for RNA markers of macrophages and inflammation in perigonadal AT and found only a trend towards an increase in the AT macrophage markers F480 and CD68 in BM-COX-1−/− mice (P<0.08) (Figure 3A). On the other hand, there was a significant increase in the AT inflammatory markers MCP-1, MIP-1α, serum amyloid A-3 (SAA-3), and Serpine-1. These data indicate that although macrophage accumulation in AT was not significant, AT inflammation was increased in mice lacking COX-1 in hematopoietic cells.

Figure 3.

Effect of hematopoietic COX-1 on AT macrophage accumulation, AT-specific inflammation, and systemic levels of adipokines in mice. The RNA samples collected from the perigonadal AT were analyzed by real time PCR for markers of macrophages and inflammatory response (A). Values are mean ± SEM of 7–8 mice in each group.. Immunofluorecence analysis was performed to detect F4/80 (B & E), MCP-1 (C & F), and MGL (D & G) in AT. The plasma levels of AT-derived adipokines such as adiponectin (H & I) and leptin (J) were determined by western blot analysis and ELISA, respectively. Values are mean ± SEM of 4–8 mice in each group. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs COX-1+/+ control.

Immunofluorescence analysis of perigonadal AT revealed that staining for both F4/80 and MCP-1 was markedly increased in the AT of BM-COX-1−/− compared to control mice. Interestingly, staining for MGL, a marker of M2 or anti-inflammatory phenotype, was remarkably reduced (Figure 3B–G). We next determined the systemic levels of leptin and adiponectin, adipose tissue-derived adipokines. Our data show that the plasma leptin level was increased and that of adiponectin was decreased significantly in BM-COX-1−/− compared to control mice (Figure 3H–J).

Emerging literature suggests that it is not the presence of macrophages which determines the inflammatory events but their polarization state towards M1 or M2 phenotype [37, 38]. Analysis of the AT SVCs for M1 and M2 markers, which are indicative of pro- and anti-inflammatory phenotypes, respectively, revealed no significant differences in M1 (MCP-1 and TNFα) or M2 markers (IL-10 and MGL-2). Interestingly, MGL-1, an M2 marker was reduced significantly in BM-COX-1−/− compared to control mice (Supplemental Figure 1). AT Glut-4 protein levels did not differ between groups. Likewise, the phosphorylation status of IR and AKT, insulin signaling markers, did not differ (Supplemental Figure 2). These data indicate that BM-COX-1−/− mice exhibit an increase in AT-specific inflammation. Since increased leptin and reduced adiponectin levels are associated with obesity-associated metabolic disorders [39], these data suggest that deletion of COX-1 in hematopoietic cells may modulate lipid and glucose homeostasis partly via alterations in the levels of these adipokines.

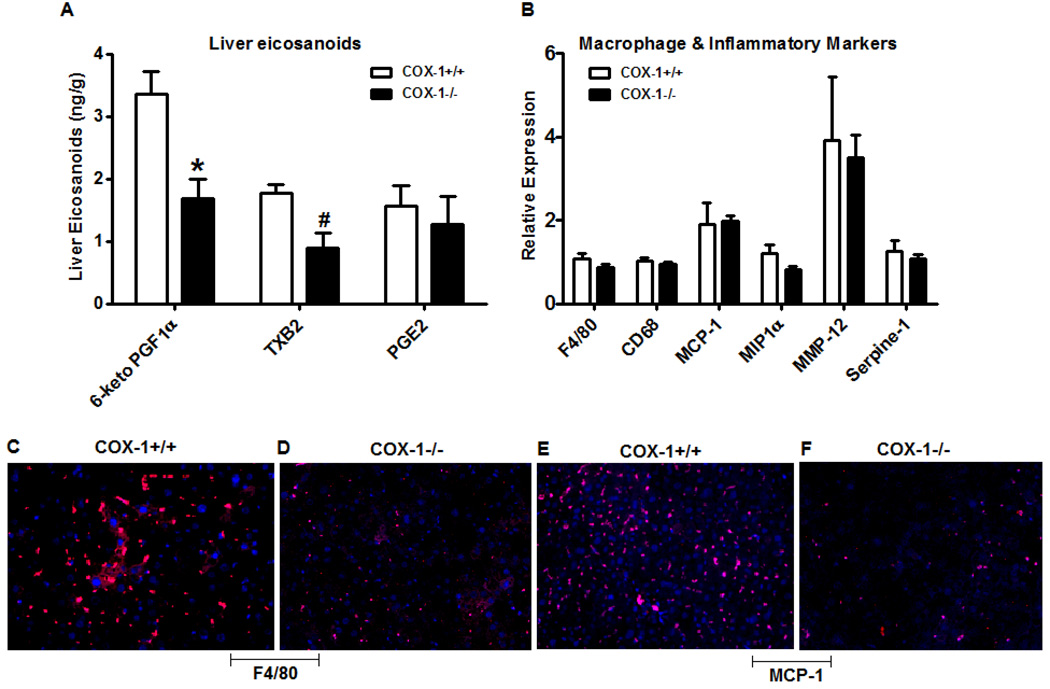

Effects of COX-1 deletion in hematopoietic cells on liver eicosanoids and hepatic inflammation in mice challenged with a high fat diet

Because obesity is often associated with hepatic inflammation, we next wanted to study the impact of hematopoietic cell COX-1 deletion in modulating the pattern of eicosanoids and the expression of inflammatory markers in the liver. As noted in Figure 4A, the levels of both 6-keto PGF1α, a stable metabolite of PGI2, and TXB2 were significantly reduced in BM-COX-1−/− compared to BM-COX-1+/+ mice, whereas the PGE2 level was not altered. The mRNA expression of macrophage markers such as F4/80 and cluster of differentiation 68 (CD68) did not differ between groups (Figure 4B). There were no significant differences in the hepatic mRNA expression of the inflammatory markers, MCP-1, macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α), matrix metalloproteinase-12 (MMP-12), or Serpine-1. Although the mRNA expression of macrophage and inflammatory markers were not altered significantly, the immunofluorescence analysis of liver sections revealed that the presence of F4/80 and MCP-1 positive cells was markedly reduced in BM-COX-1−/− compared to BM-COX-1+/+ mice (Figure 4C–F). These data show that hematopoietic deletion of COX-1 leads to decreased hepatic inflammation associated with reduced TXB2 levels.

Figure 4.

Effect of hematopoietic COX-1 on eicosanoid levels and inflammation in liver. The levels of eicosanoids such as 6-keto PGF1α, TXB2, and PGE2 were determined by GC/MS (A). The RNA samples collected from liver were analyzed by real time PCR for markers of macrophages and inflammatory response (B). Immunofluorecence analysis was performed to detect the presence of macrophage (F4/80, C & D) and inflammatory (MCP-1, E &F) markers in liver. Values are mean ± SEM of 6–8 mice in each group. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs COX-1+/+ control.

Effects of COX-1 deletion in hematopoietic cells on liver lipid accumulation in mice challenged with a high fat diet

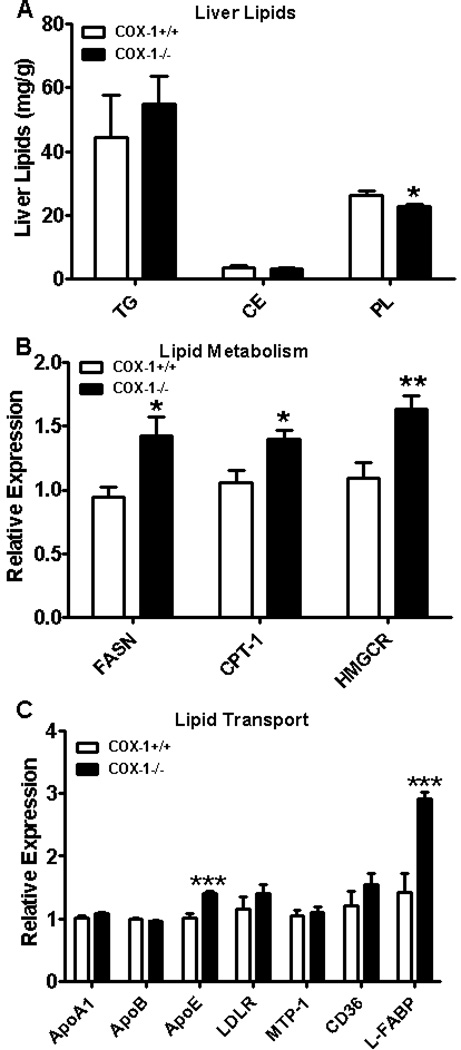

We next investigated the impact of hematopoietic cell COX-1 deletion in modulating lipid accumulation in the liver. Hepatic triglycerides, the major lipid fraction in steatotic liver, and cholesterol esters were not altered significantly in BM-COX-1−/− mice compared to control. However, there was a small but significant decrease in phospholipids in BM-COX-1−/− mice compared to BM-COX-1+/+ control mice (Figure 5A). Of note, although hepatic triglycerides and cholesterol esters were not altered in BM-COX-1−/− mice, their plasma triglycerides and total cholesterol were higher than control mice (Figure 2 E&F), indicating that the BM-COX-1−/− mice exhibit an overall impairment in lipid homeostasis.

Figure 5.

Effect of hematopoietic COX-1 on hepatic lipid accumulation and genes modulating hepatic and systemic lipid levels in mice. The levels of hepatic triglycerides, cholesterol esters, and phospholipids (A) were analyzed. The mRNA expression of genes involved in hepatic lipid metabolism (B) and lipid transport (C) was determined. Values are mean ± SEM of 7–8 mice in each group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001 vs COX-1+/+ control.

To determine whether increased hepatic fatty acid or cholesterol synthesis could account for the rise in plasma triglycerides and total cholesterol, we performed realtime PCR analysis for RNA markers of fatty acid synthesis and oxidation and cholesterol synthesis in the liver. We found increased hepatic mRNA expression of fatty acid synthase (FASN) and 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGCR), a rate limiting enzyme in cholesterol biosynthesis (Figure 5B). There was also a mild but significant increase in carnitine palmitoyl transferase-1 (CPT-1), an enzyme involved in fatty acid oxidation. Overall, the increased expression of lipogenic genes in the liver may account, at least in part, for the increase in plasma lipid levels.

An increase in lipid transport from the liver can also modulate systemic lipid levels, therefore, the expression of genes involved in this process were determined. As shown in Figure 5C, the mRNA expression of apolipoprotein E (apoE), which promotes very low density lipoprotein secretion [40, 41], was significantly increased in BM-COX-1−/− compared to BM-COX-1+/+ mice. We also noted that the expression of liver fatty acid binding protein (L-FABP), which binds with fatty acids and redirects them for oxidation or esterification into triglycerides or cholesterol esters [42], was significantly increased in BM-COX-1−/− mice. Thus, in addition to lipogenic genes, genes involved in lipid transport were also increased in BM-COX-1−/− mice.

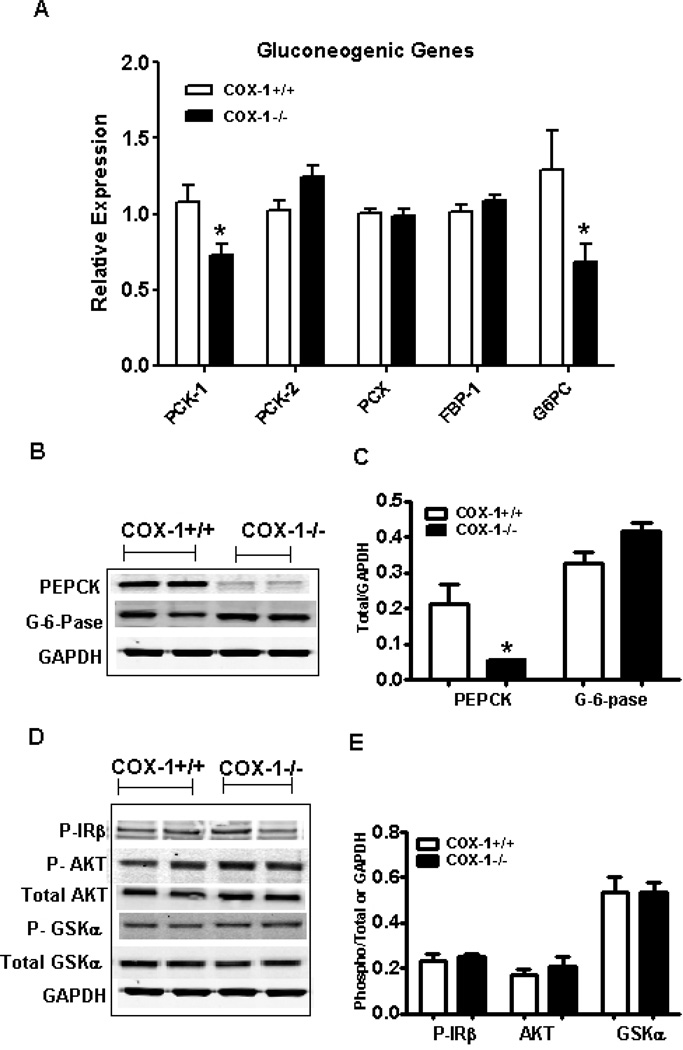

Effects of COX-1 deletion in hematopoietic cells on genes/proteins modulating hepatic glucose output in mice challenged with a high fat diet

Because fasting glucose levels were elevated in BM-COX-1−/− mice, we next measured the mRNA and protein levels of genes regulating hepatic glucose output. The mRNA levels of phosphoenol pyruvate carboxy kinase-1 (PCK-1), an important enzyme in gluconeogenesis, and glucose-6-phosphatase (G6PC), which is involved in the release of free glucose from hepatocytes, were significantly reduced in the liver of BM-COX-1−/− mice compared to control (Figure 6A). Other genes involved in gluconeogenesis such as PCK-2, pyruvate carboxylase (PCX), fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase were not altered between the two groups. Protein levels of PCK (PEPCK) but not G6PC were significantly reduced (Figure 6B&C). Finally, the phosphorylation status of AKT, GSK, and IR, which provide an index of insulin signaling in the liver, showed no significant difference in the phosphorylation of these proteins (Figure 6D&E). Since PEPCK was reduced in BM-COX-1−/− mice, it is unclear whether the liver played a role in causing the hyperglycemia.

Figure 6.

Effect of hematopoietic COX-1 on the mRNA and protein levels of genes regulating hepatic glucose metabolism. The RNA samples were analyzed by real time PCR for genes involved in hepatic glucose metabolism (A). Tissue homogenates were analyzed for the protein levels of genes involved in hepatic glucose output (B&C) and also for the phosphorylation status of enzymes mediating insulin signaling (D&E). Phospho-IRβ was analyzed after immunoprecipitation followed by western blot analysis and therefore the values are normalized to GAPDH. Phospho AKT and phospho GSKa were normalized to total AKT and GSK, respectively. Values are mean ± SEM of 7–8 mice in each group. *P<0.05 vs COX-1+/+ control.

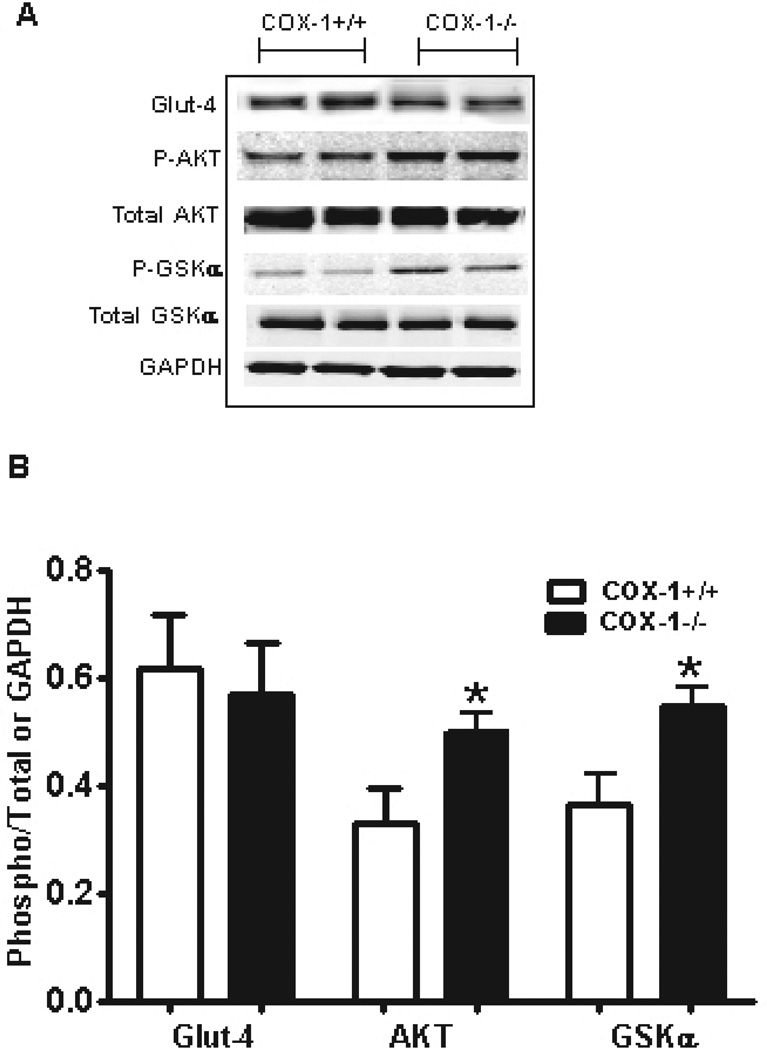

Effects of COX-1 deletion in hematopoietic cells on markers of muscle glucose uptake and metabolism in mice challenged with a high fat diet

We next determined the role of muscle in altering glucose homeostasis in BM-COX-1−/− mice. Protein lysates collected from soleus muscle were analyzed for the level of Glut-4, a major glucose transporter in muscle. There was no difference in Glut-4 levels between the two groups (Figure 7A&B). However, analysis of AKT and GSK revealed that phosphorylation of these two proteins, which are involved in muscle glucose uptake and metabolism, was significantly increased in BM-COX-1−/− compared to control mice.

Figure 7.

Effect of hematopoietic COX-1 on the levels and phosphorylation status of proteins regulating muscle glucose uptake and metabolism. Tissue homogenates collected from soleus muscle were analyzed for the level of Glut-4 and the phosphorylation status of enzymes mediating insulin signaling (A & B). Glut-4 was normalized to GAPDH and phospho AKT and GSK were normalized to total AKT and GSK, respectively. Values are mean ± SEM of 6–7 mice in each group. *P<0.05 vs COX-1+/+ control.

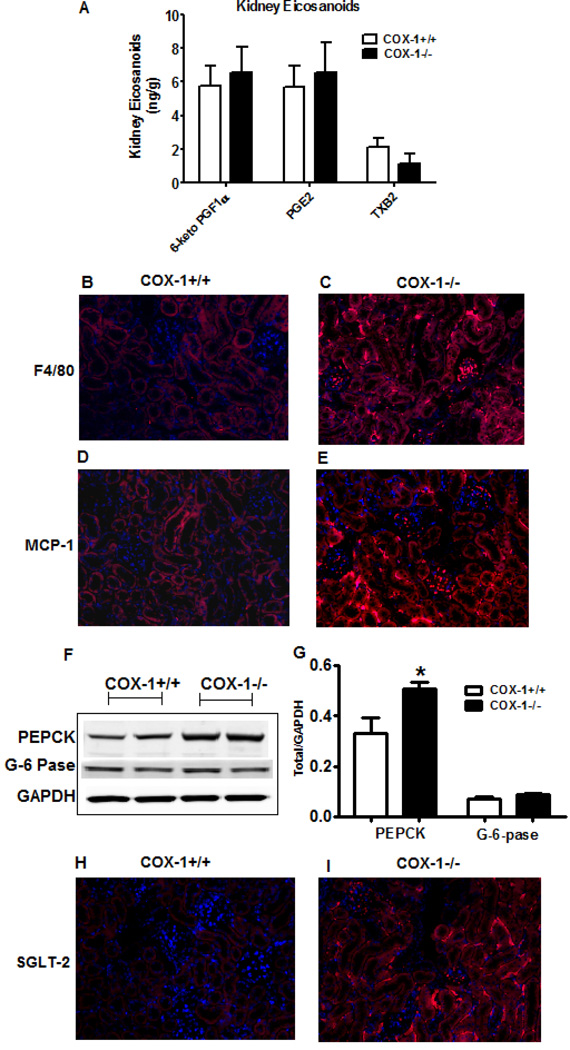

Effects of COX-1 deletion in hematopoietic cells on renal eicosanoid levels, renal inflammation and markers of renal glucose output/glucose reabsorption in mice challenged with a high fat diet

Kidneys can contribute to changes in blood glucose levels via both gluconeogenesis [43, 44]) and glucose reabsorption [45, 46]. Of note, obesity is associated with increased immune cell infiltration into kidneys [47, 48] and COX-derived eicosanoids play a major role in regulating renal function [49]. Therefore, we studied the impact of hematopoietic COX-1 deletion in modulating kidney inflammation and markers of renal glucose release. Analysis of the eicosanoid profile revealed that the levels of 6-keto PGF-1α, PGE2, and TXB2 were not altered significantly between the groups (Figure 8A). Histological analysis of kidney sections showed that both F4/80 and MCP-1 staining increased markedly in the kidneys of BM-COX-1−/− compared to control mice (Figure 8B–E). Western blot analysis of kidney samples showed that the level of PEPCK was significantly increased in BM-COX-1−/− mice while that of G6PC was not altered (Figure 8 F&G). The markers of insulin signaling including phospho AKT and phospho GSK were not altered significantly between the two groups in kidneys (data not shown). Finally, histological analysis revealed that the expression of SGLT-2, which is involved in renal glucose reabsorption, was greatly increased (Figure 8 H&I). Together, these data indicate that deletion of COX-1 in hematopoietic cells increased renal inflammation and likely renal glucose release.

Figure 8.

Effect of hematopoietic COX-1 on kidney eicosanoid levels, inflammation, and the levels of proteins involved in glucose release from kidneys. The levels of eicosanoids such as 6-keto PGF1α, PGE2, and TXB2 were determined by GC/MS (A). Immunofluorecence analysis was performed to detect the presence of macrophage (F4/80, B & C) and inflammatory (MCP-1, D & E) markers in kidneys. Tissue homogenates were analyzed for the protein levels of genes involved in renal glucose release (F & G). Immunofluorecence analysis was performed to detect the expression status of SGLT-2, a glucose transporter involved in renal glucose reabsorption (H & I). Values are mean ± SEM of 7–8 mice in each group. *P<0.05 vs COX-1+/+ control.

DISCUSSION

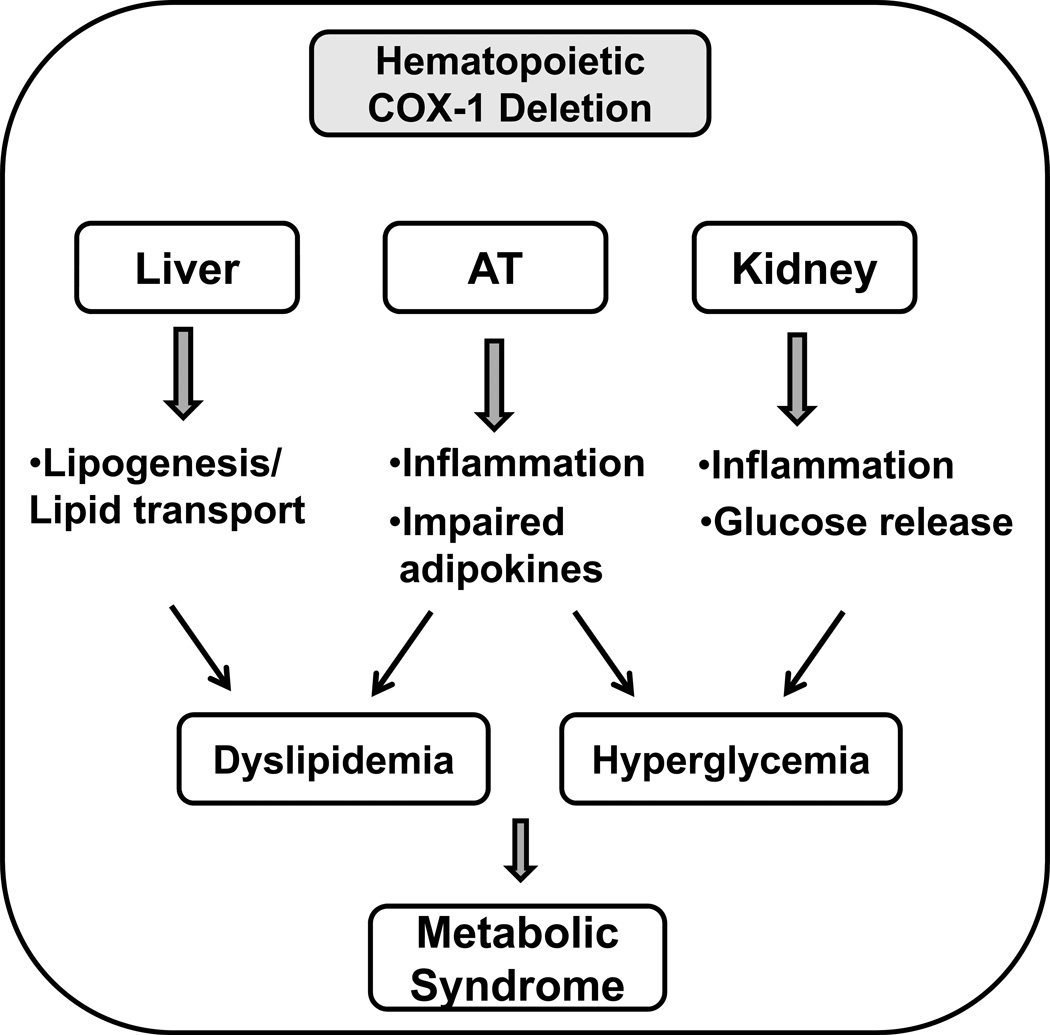

In the current study, we have demonstrated that hematopoietic deletion of COX-1 leads to an increase in AT inflammation and impairments in adipokine profile. We have also shown that BM-COX-1−/− mice exhibit an increase in fasting blood glucose and plasma lipids. Our data suggest that AT dysfunction characterized by AT inflammation and dysregulated adipokine secretion may play a role in mediating the metabolic disorders (dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia) in BM-COX-1−/− mice. Our data also suggest that increased hepatic lipogenesis/lipid transport and increased renal glucose release may play a role, at least in part, in mediating dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia, respectively, in BM-COX-1−/− mice. These data highlight the role of hematopoietic COX-1 in regulating both inflammatory as well as metabolic homeostasis in high fat diet-fed mice (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Deletion of COX-1 in hematopoietic cells leads to hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia, features of metabolic syndrome. Hematopoietic COX-1 deficiency also leads to increased AT inflammation and dysregulated systemic adipokine levels (increased leptin and decreased adiponectin). As both leptin and adiponectin modulate lipid and glucose metabolism via autocrine and paracrine mechanisms, impaired AT functions may play a role in mediating the metabolic disorders (dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia) found in BM-COX-1−/− mice. In addition, increased hepatic lipogenesis/lipid transport and increased renal glucose release may account for part of the dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia, respectively, in BM-COX-1−/− mice. Hematopoietic COX-1 plays a critical role in regulating both inflammation and metabolic disorders.

Using the BMT approach, we have demonstrated that hematopoietic deletion of COX-1 leads to impaired glucose and lipid homeostasis in obesity. Several lines of evidence suggest that hematopoietic cells have an important role in regulating glucose and lipid metabolism as well as inflammation. For example, the deletion of CCR5 and G-protein coupled receptor 21 in hematopoietic cells has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity and hepatic steatosis in mice on a high fat diet [5, 50]. In addition, hematopoietic adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) β1 reduces AT macrophage inflammation and insulin resistance in obese mice [51]. In our study we noted that hematopoietic deletion of COX-1 leads to increased blood glucose and plasma total cholesterol and triglycerides.

Another interesting finding of this study is that BM-COX-1−/− mice showed increased AT inflammation as evident from increased mRNA and/or protein levels of levels macrophage and inflammatory marker. As mentioned, it is not just the presence of macrophages but their polarization towards M1 or M2 phenotype that determines whether they exert pro- or anti-inflammatory effects. Our data show that although the M1 markers were not altered significantly in SVCs, the expression of M2 markers, in particular, MGL1, was reduced in SVCs as well as in AT per se. Because MGL1 is anti-inflammatory [52], it is likely that the AT-inflammation found in BM-COX-1−/− mice originate mainly from adipocytes rather than AT macrophages. This notion is supported by the fact that the RNA expression of SAA3, an inflammatory adipocyte-secreted acute phase protein [53] is increased in perigonadal AT of BM-COX-1−/− mice (Figure 3A).

Although AT inflammation was clearly increased, AT markers of glucose uptake and insulin signaling were not affected. However, we noted increased plasma leptin and decreased plasma adiponectin in BM-COX-1−/− mice. As these adipokines can modulate both glucose and lipid metabolism via both autocrine and paracrine mechanisms [54], it is reasonable to speculate that alterations in adipokines may contribute to the metabolic derangements in these mice.

With regard to lipid homeostasis, in addition to AT, liver plays an important role in regulating plasma lipids. Previously, Babaev et al. showed that hematopoietic deletion of COX-1 promotes the development of atherosclerotic lesions in both apolipoprotein E (apoE) and low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) deficient mice [55]. Our findings are in line with this study and show that BM-COX-1−/− mice display dyslipidemia, a risk factor for atherosclerosis, and provide novel evidence for the role of COX-1 in regulating lipid homeostasis. Increased plasma total cholesterol and triglycerides in BM-COX-1−/− mice appear to be mediated via increased hepatic lipogenesis and lipid transport. Of note, these mice also exhibited a mild but significant increase in CPT-1, which is involved in fatty acid β-oxidation. We also noted that L-FABP expression was significantly increased in BM-COX-1−/− mice compared to control. As mentioned, this protein binds with fatty acids and redirects them for either oxidation or esterification into triglycerides and cholesterol esters. Because the systemic levels of both total cholesterol and triglycerides were increased, it is possible that the dyslipidemia resulting from hematopoietic COX-1 deletion is due, at least in part, to increased hepatic lipogenesis and lipid transport from liver.

As for the potential biochemical mechanisms involved in mediating the dyslipidemic effects seen in BM-COX-1−/− mice, COX-derived PGI2 is implicated in regulating hepatic lipid metabolism. For example, analogs of PGI2 have been shown to be effective in reducing hepatic steatosis and dyslipidemia in mouse models [56, 57], and this effect has been shown to be mediated via reduced hepatic lipogenesis [56]. Our data show that the hepatic level of 6-keto PGF1α, a stable metabolite of PGI2, is significantly reduced in BM-COX-1−/− mice suggesting that reduced PGI2 may have a role in mediating dyslipidemia in these mice. We also noted that hepatic inflammation is lower in BM-COX-1−/− mice, associated with reduced TXB2 levels, consistent with the effect of TXs in mediating inflammation. Taken together, the liver data indicate that deletion of COX-1 in hematopoietic cells impair hepatic lipid metabolism and attenuate hepatic inflammation, likely via reduced PGI2 and TXB2 levels, respectively. Whether the liver plays a role in mediating fasting hyperglycemia is unclear.

Analysis of soleus muscle revealed that the phosphorylation of AKT and GSK are significantly increased in BM-COX-1−/− mice, thereby indicating that the muscle glucose uptake and metabolism may be increased in these mice to balance the elevated blood glucose. Therefore, it appears that impaired muscle glucose uptake may not be a reason for the elevated fasting glucose in these mice.

COX-derived metabolites have an integral role in regulating kidney function [49]). Analysis of kidney samples revealed that markers of gluconeogenesis and glucose reabsorption were increased in BM-COX-1−/− mice suggesting that increased glucose release from kidneys may have had a role, at least in part, in the perturbed glucose homeostasis. It should be noted that liver is considered to be the main gluconeogenic organ but studies have shown that renal gluconeogenesis accounts for about 25% of systemic glucose production [58]. This increases to 50% during specific conditions like starvation and diabetes mellitus [59]. Because kidneys can also contribute to blood glucose levels via glucose reabsorption [45, 46], our data suggest that an increase renal glucose release may have a role in altering blood glucose homeostasis in BM-COX-1−/− mice. With regard to the renal eicosanoid levels, there were no significant differences in any of the eicosanoids that were measured. This may be due to the fact that both COX-1 and −2 are highly expressed in kidneys and therefore the subtle changes caused by selective hematopoietic COX-1 deletion may not be as obvious. Regardless of the amount of eicosanoids, the kidney inflammation was greatly increased in BM-COX-1−/− mice compared to control. One plausible reason is that kidneys express various eicosanoid receptors and deletion of COX-1 in hematopoietic cells could have led to increased expression/activation of specific receptors mediating the inflammatory response [60]. Further studies are needed to test this hypothesis.

The major strength of this study is the novelty of findings. First, there is an increase in AT inflammation and alterations in the pattern of leptin and adiponectin in BM-COX-1−/− mice. Second, BM-COX-1−/− mice exhibit hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia, characteristics of the metabolic syndrome. Third, there are reductions in hepatic inflammation and the levels of TXB2 and PGI2 in the liver. In addition, hepatic expression of lipogenic and lipid transport genes is increased. Finally, our data show that hematopoietic COX-1 deficiency leads to increased kidney inflammation and elevation of proteins involved in renal glucose release. Taken together, our data indicate that hematopoietic COX-1 plays an important role in regulating both inflammation and metabolic homeostasis.

There are several questions that will be important for future studies to address. For example, it is not yet known how BM-COX-1- mice will respond to insulin or glucose tolerance tests. In addition, energy expenditure experiments need to be performed to determine whether the increase in AT mass and/or impairments in metabolic profile are due to reduced energy expenditure. Finally, it will be important to measure markers of insulin signaling in insulin-stimulated conditions.

The translational potential of these findings is high. For example, the increase in markers of renal gluconeogenesis and glucose reabsorption are increased in BM-COX-1−/− mice, suggesting that impairments in kidney functions may have a role in the development or exacerbation of metabolic disorders. Of particular interest, SGLT-2 inhibitors have been recently approved to treat type 2 diabetes. Our data suggest that hematopoietic cell-derived eicosanoids may impact the expression levels of SGLT-2 in kidneys. Thus, understanding the role of hematopoietic COX-1 in maintaining both inflammatory and metabolic homeostasis in obesity is important.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project was supported by the American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant (0930335N) and a Pilot and Feasibility Grant from the Digestive Disease Research Center at Vanderbilt University (DK058404) to V. Saraswathi. Lipid profiles were performed at the Lipid Core Laboratory of the Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center at Vanderbilt University (DK59637). We would like to thank Dr. Alyssa Hasty for providing the technical support to perform the bone marrow transplantation procedure in this study. This paper is the result of work conducted with the resources and the facilities at the VA-Nebraska Western Iowa Health Care System, Omaha.

List of abbreviations used

- AT

adipose tissue

- AMPK

adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

- apoE

apolipoprotein E

- BMT

bone marrow transplantation

- CCR2

CC chemokine receptor-2

- CCR5

CC chemokine receptor-5

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- COX-1+/+

wild type

- COX-1−/−

COX-1 knock-out

- CD68

cluster of differentiation 68

- CPT-1

carnitine palmitoyl transferase-1

- DAPI

4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- F4/80

murine homologue of EGF-like module-containing mucin-like hormone receptor-like 1

- FASN

fatty acid synthase

- FBP-1

fructose 1,6 bisphosphatase

- G6PC

glucose-6-phosphatase

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3 phosphate dehydrogenase

- GC/MS

gas chromatography/mass spectrometry

- Glut-4

glucose transporter-4

- GSK

glycogen synthase kinase

- HMGCR

3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase

- HOMA-IR

homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance

- IL

interleukin

- IR-β

phospho insulin receptor beta

- L-FABP

liver fatty acid binding protein

- LDLR

low density lipoprotein receptor

- MGL

macrophage galactose type lectin

- MIP-1α

macrophage inflammatory protein-1α

- MCP-1

monocyte chemoattractant protein

- MMP-12

matrix metalloproteinase-12

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- PCK-1 and PEPCK

phosphoenol pyruvate carboxykinase

- PCX

pyruvate carboxylase

- PG

prostaglandin

- SAA-3

serum amyloid A-3

- SGLT-2

sodium glucose cotransporter-2

- SVC

stromal vascular cells

- TLR4

toll-like receptor 4

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TX

thromboxane

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest: None

Authors’ contributions: All authors contributed in the interpretation of the studies and review of the manuscript; CJR, AWW, AAE, GM, RR, GLM, and KCC conducted the experiments; and VS conducted the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Olefsky JM, Glass CK. Macrophages, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:219–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van de Woestijne AP, Monajemi H, Kalkhoven E, et al. Adipose tissue dysfunction and hypertriglyceridemia: Mechanisms and management. Obes Rev. 2011;12(10):829–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cusi K. Role of obesity and lipotoxicity in the development of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Pathophysiology and clinical implications. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(4):711–725. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.02.003. e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanda H, Tateya S, Tamori Y, et al. Mcp-1 contributes to macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in obesity. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(6):1494–1505. doi: 10.1172/JCI26498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitade H, Sawamoto K, Nagashimada M, et al. Ccr5 plays a critical role in obesity-induced adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance by regulating both macrophage recruitment and m1/m2 status. Diabetes. 2012;61(7):1680–1690. doi: 10.2337/db11-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saberi M, Woods NB, de Luca C, et al. Hematopoietic cell-specific deletion of toll-like receptor 4 ameliorates hepatic and adipose tissue insulin resistance in high-fat-fed mice. Cell Metab. 2009;10(5):419–429. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith WL, Dewitt DL. Prostaglandin endoperoxide h synthases-1 and −2. Adv Immunol. 1996;62:167–215. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60430-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghoshal S, Trivedi DB, Graf GA, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 deficiency attenuates adipose tissue differentiation and inflammation in mice. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(1):889–898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.139139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsieh PS, Lu KC, Chiang CF, et al. Suppressive effect of cox2 inhibitor on the progression of adipose inflammation in high-fat-induced obese rats. Eur J Clin Invest. 2010;40(2):164–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith WL, DeWitt DL, Garavito RM. Cyclooxygenases: Structural, cellular, and molecular biology. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:145–182. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Sullivan MG, Chilton FH, Huggins EM, Jr., et al. Lipopolysaccharide priming of alveolar macrophages for enhanced synthesis of prostanoids involves induction of a novel prostaglandin h synthase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(21):14547–14550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunkel SL, Chensue SW, Phan SH. Prostaglandins as endogenous mediators of interleukin 1 production. J Immunol. 1986;136(1):186–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajakariar R, Yaqoob MM, Gilroy DW. Cox-2 in inflammation and resolution. Mol Interv. 2006;6(4):199–207. doi: 10.1124/mi.6.4.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilroy DW, Lawrence T, Perretti M, et al. Inflammatory resolution: New opportunities for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3(5):401–416. doi: 10.1038/nrd1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Francois H, Makhanova N, Ruiz P, et al. A role for the thromboxane receptor in l-name hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295(4):F1096–F1102. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00369.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ge T, Hughes H, Junquero DC, et al. Endothelium-dependent contractions are associated with both augmented expression of prostaglandin h synthase-1 and hypersensitivity to prostaglandin h2 in the shr aorta. Circ Res. 1995;76(6):1003–1010. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.6.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heymes C, Habib A, Yang D, et al. Cyclo-oxygenase-1 and −2 contribution to endothelial dysfunction in ageing. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;131(4):804–810. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu T, Laidlaw TM, Feng C, et al. Prostaglandin e2 deficiency uncovers a dominant role for thromboxane a2 in house dust mite-induced allergic pulmonary inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(31):12692–12697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207816109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takayama K, Yuhki K, Ono K, et al. Thromboxane a2 and prostaglandin f2alpha mediate inflammatory tachycardia. Nat Med. 2005;11(5):562–566. doi: 10.1038/nm1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hishinuma T, Tsukamoto H, Suzuki K, et al. Relationship between thromboxane/prostacyclin ratio and diabetic vascular complications. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2001;65(4):191–196. doi: 10.1054/plef.2001.0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lasserre B, Navarro-Delmasure C, Pham Huu Chanh A, et al. Modifications in the txa(2) and pgi(2) plasma levels and some other biochemical parameters during the initiation and development of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (niddm) syndrome in the rabbit. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2000;62(5):285–291. doi: 10.1054/plef.2000.0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basili S, Pacini G, Guagnano MT, et al. Insulin resistance as a determinant of platelet activation in obese women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(12):2531–2538. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, et al. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(12):1796–1808. doi: 10.1172/JCI19246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Taeye BM, Novitskaya T, McGuinness OP, et al. Macrophage tnf-alpha contributes to insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis in diet-induced obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293(3):E713–E725. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00194.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atkinson RD, Coenen KR, Plummer MR, et al. Macrophage-derived apolipoprotein e ameliorates dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis in obese apolipoprotein e-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;294(2):E284–E290. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00601.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langenbach R, Morham SG, Tiano HF, et al. Prostaglandin synthase 1 gene disruption in mice reduces arachidonic acid-induced inflammation and indomethacin-induced gastric ulceration. Cell. 1995;83(3):483–492. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saraswathi V, Gao L, Morrow JD, et al. Fish oil increases cholesterol storage in white adipose tissue with concomitant decreases in inflammation, hepatic steatosis, and atherosclerosis in mice. J Nutr. 2007;137(7):1776–1782. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.7.1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saraswathi V, Morrow JD, Hasty AH. Dietary fish oil exerts hypolipidemic effects in lean and insulin sensitizing effects in obese ldlr−/− mice. J Nutr. 2009;139(12):2380–2386. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.111567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orr JS, Puglisi MJ, Ellacott KL, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 deficiency promotes the alternative activation of adipose tissue macrophages. Diabetes. 2012;61(11):2718–2727. doi: 10.2337/db11-1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Surmi BK, Atkinson RD, Gruen ML, et al. The role of macrophage leptin receptor in aortic root lesion formation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;294(3):E488–E495. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00374.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang S, Yajima H, Huynh H, et al. Congenital bone marrow failure in DNA-pkcs mutant mice associated with deficiencies in DNA repair. J Cell Biol. 2011;193(2):295–305. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201009074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murali G, Milne GL, Webb CD, et al. Fish oil and indomethacin in combination potently reduce dyslipidemia and hepatic steatosis in ldlr(−/−) mice. J Lipid Res. 2012;53(10):2186–2197. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M029843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takano T, Cybulsky AV, Cupples WA, et al. Inhibition of cyclooxygenases reduces complement-induced glomerular epithelial cell injury and proteinuria in passive heymann nephritis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305(1):240–249. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.043604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warner TD, Giuliano F, Vojnovic I, et al. Nonsteroid drug selectivities for cyclo-oxygenase-1 rather than cyclo-oxygenase-2 are associated with human gastrointestinal toxicity: A full in vitro analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(13):7563–7568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wibberley A, McCafferty GP, Evans C, et al. Dual, but not selective, cox-1 and cox-2 inhibitors, attenuate acetic acid-evoked bladder irritation in the anaesthetised female cat. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148(2):154–161. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(12):1821–1830. doi: 10.1172/JCI19451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lumeng CN, Bodzin JL, Saltiel AR. Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage polarization. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(1):175–184. doi: 10.1172/JCI29881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Odegaard JI, Ricardo-Gonzalez RR, Goforth MH, et al. Macrophage-specific ppargamma controls alternative activation and improves insulin resistance. Nature. 2007;447(7148):1116–1120. doi: 10.1038/nature05894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harwood HJ., Jr. The adipocyte as an endocrine organ in the regulation of metabolic homeostasis. Neuropharmacology. 2012;63(1):57–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maugeais C, Tietge UJ, Tsukamoto K, et al. Hepatic apolipoprotein e expression promotes very low density lipoprotein-apolipoprotein b production in vivo in mice. J Lipid Res. 2000;41(10):1673–1679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mensenkamp AR, van Luyn MJ, van Goor H, et al. Hepatic lipid accumulation, altered very low density lipoprotein formation and apolipoprotein e deposition in apolipoprotein e3-leiden transgenic mice. J Hepatol. 2000;33(2):189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80359-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Atshaves BP, Martin GG, Hostetler HA, et al. Liver fatty acid-binding protein and obesity. J Nutr Biochem. 2010;21(11):1015–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mutel E, Gautier-Stein A, Abdul-Wahed A, et al. Control of blood glucose in the absence of hepatic glucose production during prolonged fasting in mice: Induction of renal and intestinal gluconeogenesis by glucagon. Diabetes. 2011;60(12):3121–3131. doi: 10.2337/db11-0571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pillot B, Soty M, Gautier-Stein A, et al. Protein feeding promotes redistribution of endogenous glucose production to the kidney and potentiates its suppression by insulin. Endocrinology. 2009;150(2):616–624. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki M, Honda K, Fukazawa M, et al. Tofogliflozin, a potent and highly specific sodium/glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, improves glycemic control in diabetic rats and mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;341(3):692–701. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.191593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Luippold G, Klein T, Mark M, et al. Empagliflozin, a novel potent and selective sglt-2 inhibitor, improves glycaemic control alone and in combination with insulin in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats, a model of type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(7):601–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2012.01569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coimbra TM, Janssen U, Grone HJ, et al. Early events leading to renal injury in obese zucker (fatty) rats with type ii diabetes. Kidney Int. 2000;57(1):167–182. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ma LJ, Corsa BA, Zhou J, et al. Angiotensin type 1 receptor modulates macrophage polarization and renal injury in obesity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;300(5):F1203–F1213. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00468.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hao CM, Breyer MD. Physiological regulation of prostaglandins in the kidney. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:357–377. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Osborn O, Oh DY, McNelis J, et al. G protein-coupled receptor 21 deletion improves insulin sensitivity in diet-induced obese mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(7):2444–2453. doi: 10.1172/JCI61953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Galic S, Fullerton MD, Schertzer JD, et al. Hematopoietic ampk beta1 reduces mouse adipose tissue macrophage inflammation and insulin resistance in obesity. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(12):4903–4915. doi: 10.1172/JCI58577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saba K, Denda-Nagai K, Irimura T. A c-type lectin mgl1/cd301a plays an anti-inflammatory role in murine experimental colitis. Am J Pathol. 2009;174(1):144–152. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sommer G, Weise S, Kralisch S, et al. The adipokine saa3 is induced by interleukin-1beta in mouse adipocytes. J Cell Biochem. 2008;104(6):2241–2247. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lara-Castro C, Fu Y, Chung BH, et al. Adiponectin and the metabolic syndrome: Mechanisms mediating risk for metabolic and cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2007;18(3):263–270. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32814a645f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Babaev VR, Ding L, Reese J, et al. Cyclooxygenase-1 deficiency in bone marrow cells increases early atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein e- and low-density lipoprotein receptor-null mice. Circulation. 2006;113(1):108–117. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.591537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Watanabe M, Nakashima H, Ito K, et al. Improvement of dyslipidemia in oletf rats by the prostaglandin i(2) analog beraprost sodium. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2010;93(1–2):14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sato N, Kaneko M, Tamura M, et al. The prostacyclin analog beraprost sodium ameliorates characteristics of metabolic syndrome in obese zucker (fatty) rats. Diabetes. 2010;59(4):1092–1100. doi: 10.2337/db09-1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stumvoll M, Meyer C, Mitrakou A, et al. Renal glucose production and utilization: New aspects in humans. Diabetologia. 1997;40(7):749–757. doi: 10.1007/s001250050745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Adrogue HJ. Glucose homeostasis and the kidney. Kidney Int. 1992;42(5):1266–1282. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Breyer MD, Jacobson HR, Breyer RM. Functional and molecular aspects of renal prostaglandin receptors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7(1):8–17. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.