Abstract

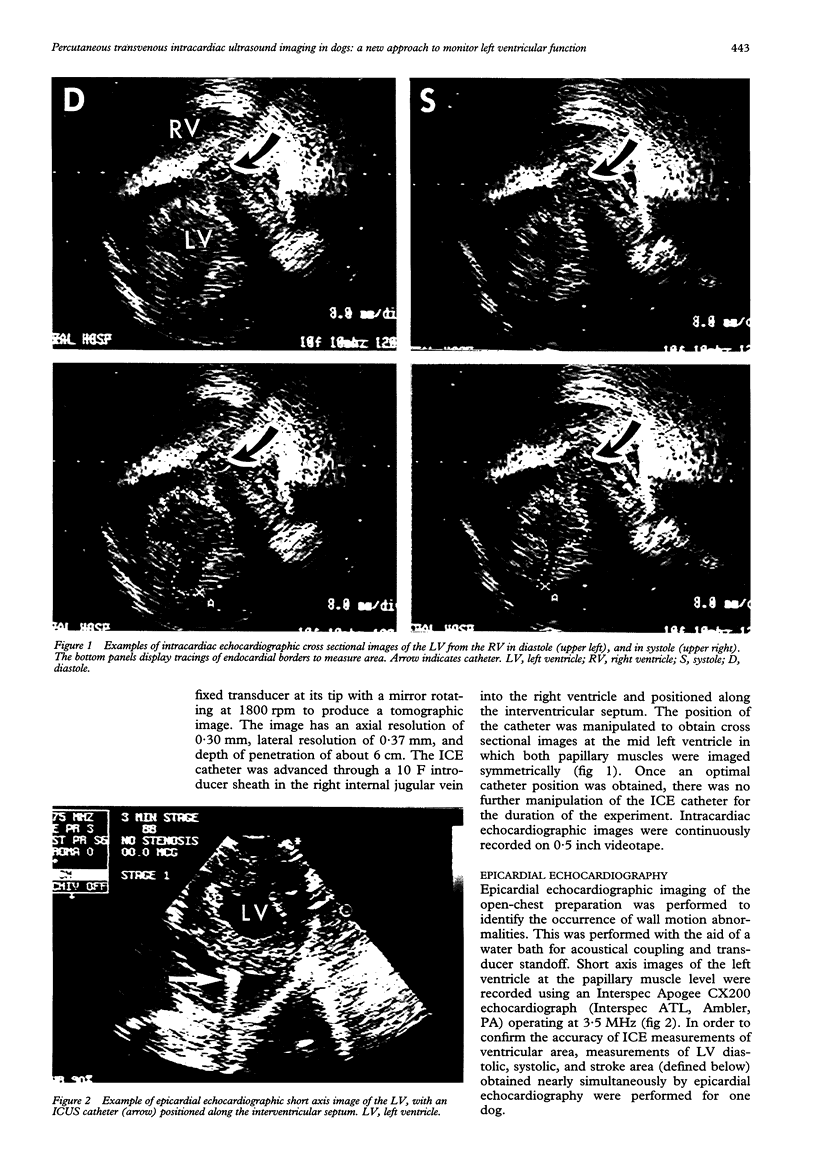

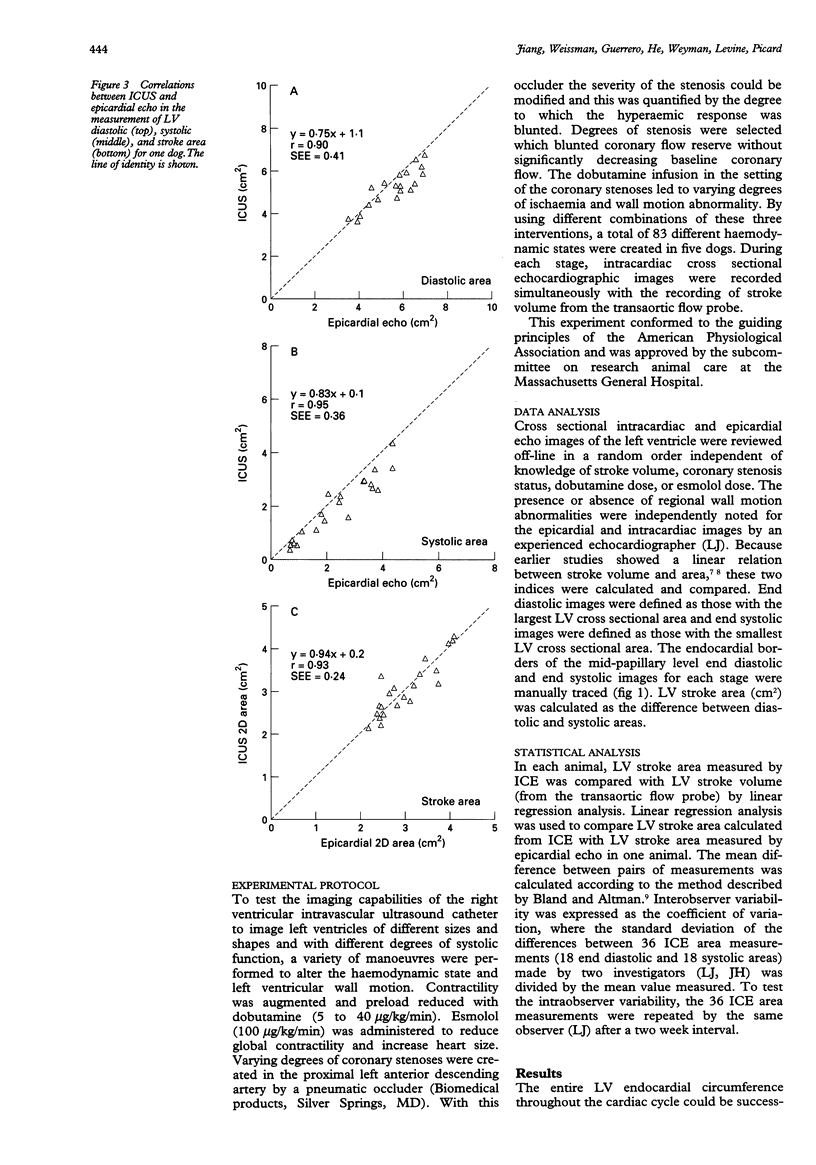

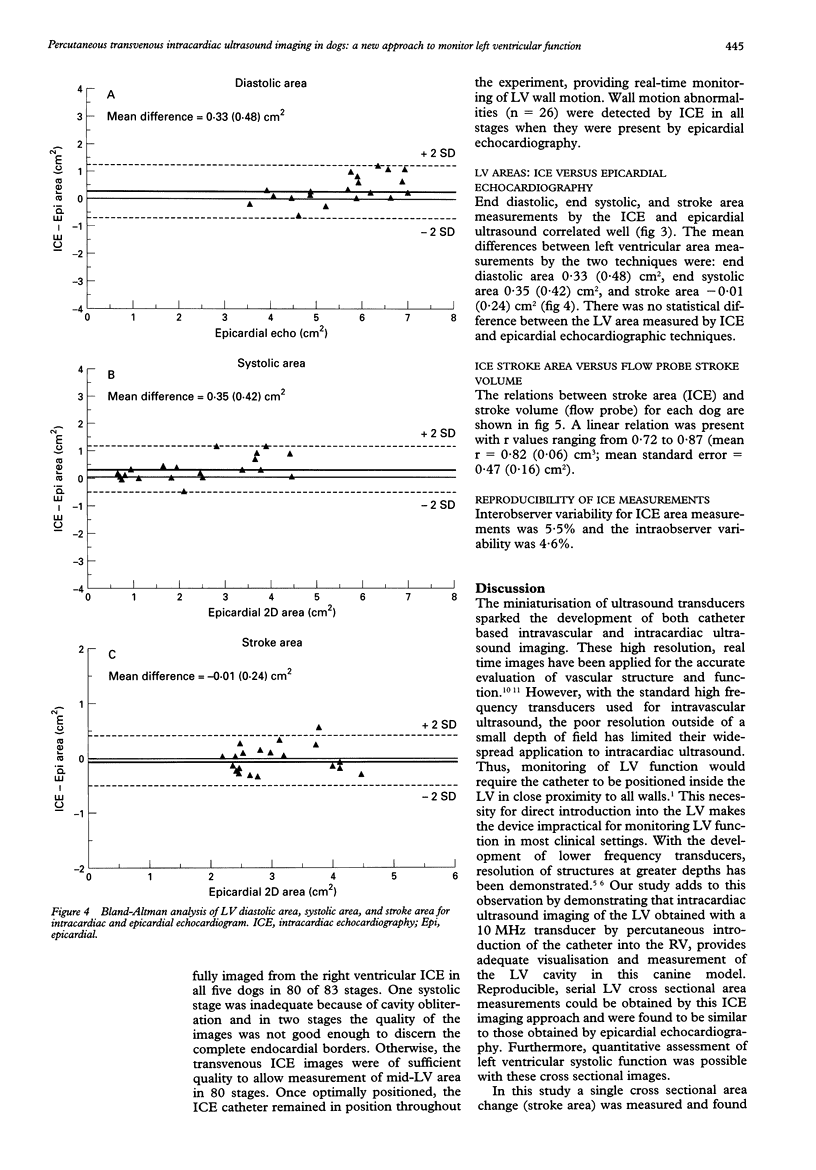

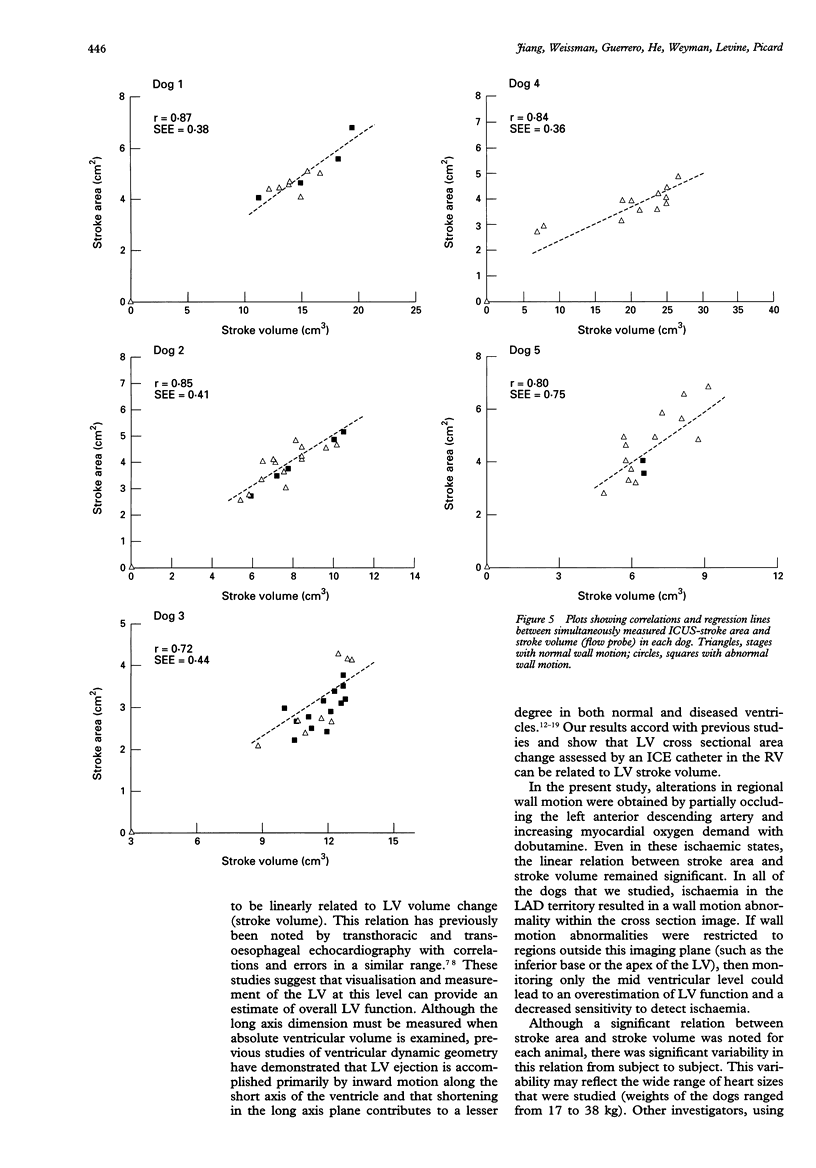

OBJECTIVE: To evaluate the feasibility and ability of percutaneous transvenous intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) to image the left ventricle (LV) and monitor its function from the right ventricular (RV) cavity. METHODS: A 10 MHz catheter was advanced into the RV from the jugular vein and positioned along the septum at the LV papillary muscle level in five dogs. The catheter was manipulated until a stable catheter position along the septum, which provided on-axis images of LV, was obtained. Different states of LV size and systolic function (n = 80) were created with dobutamine or esmolol, both in the presence and absence of coronary stenoses. LV stroke area (cm2) obtained by ICE was measured at the mid-ventricular level and compared with stroke volume (cm3) obtained simultaneously with a transaortic flow probe. LV end diastolic, end systolic, and stroke areas obtained by ICE were also compared with those obtained by short-axis epicardial echocardiography. RESULTS: In 96% of the stages, short axis images of the LV could be obtained and measured by ICE. LV end diastolic, end systolic, and stroke areas measured by ICE were not significantly different from epicardial echocardiographic values. Stroke area correlated with stroke volume in each dog (mean correlation coefficient 0.79 (SEE 0.19) cm2) (P < 0.001). CONCLUSIONS: Percutaneous intracardiac ultrasound imaging allows monitoring of LV function from the RV with an accuracy comparable to a short-axis epicardial echocardiogram. The present device can be used in closed chest experimental studies. With the development of lower frequency devices, this technique may be valuable for continuous monitoring of LV function in patients in the intensive care unit or operating room.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Appleyard R. F., Glantz S. A. Two dimensions describe left ventricular volume change during hemodynamic transients. Am J Physiol. 1990 Jan;258(1 Pt 2):H277–H284. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.1.H277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benkeser P. J., Churchwell A. L., Lee C., Abouelnasr D. M. Resolution limitations in intravascular ultrasound imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1993 Mar-Apr;6(2):158–165. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(14)80486-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop V. S., Horwitz L. D. Left ventricular transverse internal diameter: value in studying left ventricular function. Am Heart J. 1970 Oct;80(4):507–514. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(70)90199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland J. M., Altman D. G. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986 Feb 8;1(8476):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Guerrero J. L., Vazquez de Prada J. A., Padial L. R., Schwammenthal E., Chen M. H., Jiang L., Svizzero T., Simon H., Thomas J. D. Intracardiac ultrasound measurement of volumes and ejection fraction in normal, infarcted, and aneurysmal left ventricles using a 10-MHz ultrasound catheter. Circulation. 1994 Sep;90(3):1481–1491. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.3.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Mario C., Madretsma S., Linker D., The S. H., Bom N., Serruys P. W., Gussenhoven E. J., Roelandt J. R. The angle of incidence of the ultrasonic beam: a critical factor for the image quality in intravascular ultrasonography. Am Heart J. 1993 Feb;125(2 Pt 1):442–448. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(93)90024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J. P., Wolfberg C. A., Mikan J. S., Kiernan F. J., Fram D. B., McKay R. G., Gillam L. D. Intracardiac ultrasound determination of left ventricular volumes: in vitro and in vivo validation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994 Jul;24(1):247–253. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90570-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald P. J., Ports T. A., Yock P. G. Contribution of localized calcium deposits to dissection after angioplasty. An observational study using intravascular ultrasound. Circulation. 1992 Jul;86(1):64–70. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorcsan J., 3rd, Gasior T. A., Mandarino W. A., Deneault L. G., Hattler B. G., Pinsky M. R. On-line estimation of changes in left ventricular stroke volume by transesophageal echocardiographic automated border detection in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Cardiol. 1993 Sep 15;72(9):721–727. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90892-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorcsan J., 3rd, Lazar J. M., Romand J., Pinsky M. R. On-line estimation of stroke volume by means of echocardiographic automated border detection in the canine left ventricle. Am Heart J. 1993 May;125(5 Pt 1):1316–1323. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(93)91001-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorcsan J., 3rd, Romand J. A., Mandarino W. A., Deneault L. G., Pinsky M. R. Assessment of left ventricular performance by on-line pressure-area relations using echocardiographic automated border detection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994 Jan;23(1):242–252. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90527-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawthorne E. W. Symposium on measurements of left ventricular volume. 3. Dynamic geometry of the left ventricle. Am J Cardiol. 1966 Oct;18(4):566–573. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(66)90012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leshin S. J., Mullins C. B., Templeton G. H., Mitchell J. H. Dimensional analysis of ventricular function: effects of anesthetics and thoracotomy. Am J Physiol. 1972 Mar;222(3):540–545. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1972.222.3.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis R. P., Sandler H. Relationship between changes in left ventricular dimensions and the ejection fraction in man. Circulation. 1971 Oct;44(4):548–557. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.44.4.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUSHMER R. F., THAL N. The mechanics of ventricular contraction; a cinefluorographic study. Circulation. 1951 Aug;4(2):219–228. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.4.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin J. S., McHale P. A., Arentzen C. E., Ling D., Greenfield J. C., Jr, Anderson R. W. The three-dimensional dynamic geometry of the left ventricle in the conscious dog. Circ Res. 1976 Sep;39(3):304–313. doi: 10.1161/01.res.39.3.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S. L., Pandian N. G., Crowley R., Kumar R. Intracardiac echocardiography without fluoroscopy: potential of a balloon-tipped, flow-directed ultrasound catheter. Am Heart J. 1995 Mar;129(3):598–603. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(95)90290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S. L., Pandian N. G., Hsu T. L., Weintraub A., Cao Q. L. Intracardiac echocardiographic imaging of cardiac abnormalities, ischemic myocardial dysfunction, and myocardial perfusion: studies with a 10 MHz ultrasound catheter. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1993 Jul-Aug;6(4):345–355. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(14)80233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobis J. M., Mallery J., Mahon D., Lehmann K., Zalesky P., Griffith J., Gessert J., Moriuchi M., McRae M., Dwyer M. L. Intravascular ultrasound imaging of human coronary arteries in vivo. Analysis of tissue characterizations with comparison to in vitro histological specimens. Circulation. 1991 Mar;83(3):913–926. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.3.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walley K. R., Grover M., Raff G. L., Benge J. W., Hannaford B., Glantz S. A. Left ventricular dynamic geometry in the intact and open chest dog. Circ Res. 1982 Apr;50(4):573–589. doi: 10.1161/01.res.50.4.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]