Abstract

Lupus erythematosus panniculitis (LEP) is a variant of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE). Reported cases of LEP lesions before the diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) were very rare; only 9 cases have been reported, to the best of our knowledge. We now describe the case of a 19-year-old male patient, with an overall review of the English literature. In the earliest stage of the present case, nodules and ulcers involved his left leg and face, with no other accompanied symptoms. The skin lesions disappeared after treatment with methylprednisolone, 16 mg/d for 1 month. Seven months after discontinuing methylprednisolone, the cutaneous nodules and ulcers on his back recurred and were accompanied by fever, hair loss, and polyarthritis. Blood tests revealed leucopenia, positive antinuclear antibody and Smith antibody, and proteinuria. Histopathological findings were most consistent with LEP. This was followed sequentially by the diagnosis of SLE. The patient improved again after treatment with methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide.

Patients with LEP should have regular follow-ups because the development of SLE is possible. Early diagnosis and proper treatment is pivotal to improve the prognosis of such patients.

INTRODUCTION

Lupus erythematosus panniculitis (LEP), also called lupus erythematosus profundus, is a rare variant of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE).1–4 LEP commonly presents in the third-to-sixth decades of life, with female predilection. The most frequent cutaneous manifestations are indurated plaques or subcutaneous nodules, and sometimes ulcerations. The lesions occur predominantly on the face, upper arms, upper trunk, breasts, buttocks, and thighs.1–4 LEP is not a typical cutaneous manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), but individuals with LEP developing finally into SLE have been reported.5–9 Herein, we describe a male patient with SLE who initially presented with LEP lesions.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 19-year-old male patient presented with a 1-year history of recurrent asymptomatic erythematosus nodules and ulcers involving his left leg, face, and back. Initially, the patient had several nodules distributed on his left thigh and face without other systemic manifestations. Within 1 month, some of the nodules became ulcerous. Blood tests revealed positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) 56 U/mL (normal 0–12 U/mL) and antiribonucleoprotein (RNP) antibody. The following were unremarkable: complete blood count (CBC), double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibody, anti-Ro (SSA) antibody, anti-La (SSB) antibody, and urinalysis. The doctor suspected lupus erythematosus, and treated him with a methylprednisolone regimen, 16 mg/d. One month later, the skin lesions were improved significantly. Then the patient discontinued the medication. Seven months later, the patient was admitted to our department because of multiple ulcers and scattered erythematosus nodules developing on his back. The lesions presented initially as nodules but enlarged and ulcerated in a short period. Fever, hair loss, and polyarthritis accompanied the recurrence.

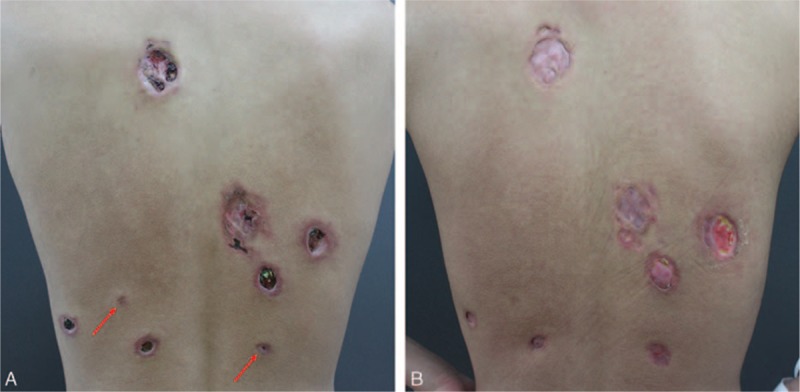

On physical examination, the patient's body temperature was 37.2°C. Two red subcutaneous nodules and multiple well-defined deep ulcers were observed on his back. The ulcers were irregular in size and shape, from 5 mm to 5 cm, with a red-violet raised edge and a pitchy crust in the center (Figure 1A). Diffuse hair loss and scarring alopecia on the occipital scalp were observed. The remaining systemic examination was normal.

FIGURE 1.

(A) Two red subcutaneous nodules (red arrows) and multiple well-defined deep ulcers on the patient's back. (B) After 2 months of treatment, the ulcers and nodules had substantially improved.

Routine blood examination showed leucopenia (total: 3.41 × 109/L, neutrophils: 79.1%). Immunologic tests revealed positive results for ANA 643.47 U/mL (normal 0–12 U/mL), anti-RNP antibody, and Smith antibody, but dsDNA antibody, SSA antibody, and SSB antibody were negative. Serum complement levels were slightly low in component (C)3: 0.69 g/L (normal 0.79–1.17 g/L), and normal in C4. Other tests included a high erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 46 mm/hour (normal range: 0–20 mm/hour) and proteinuria 0.3 g/24 hours (normal range: 0–0.15 g/24 hours).

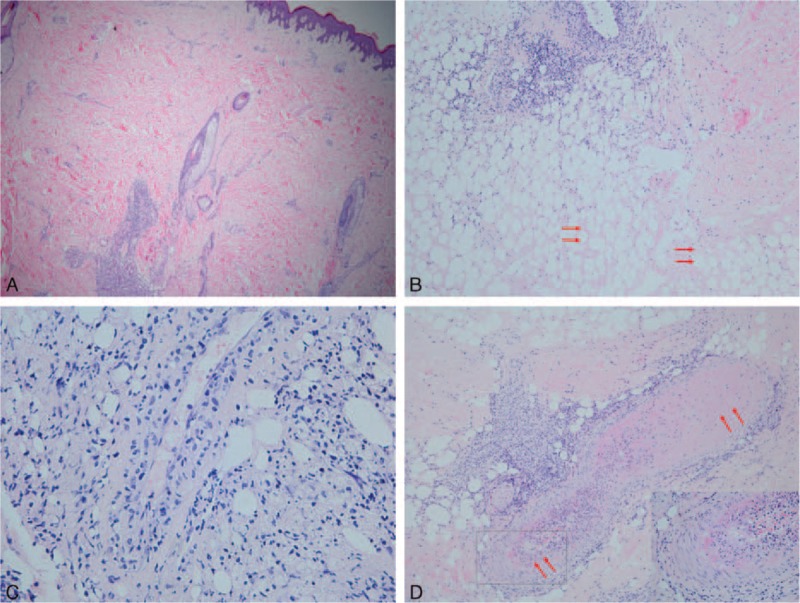

A skin biopsy was taken from a nodule. Histopathologic section showed perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrations from the upper dermis to the deep dermis (Figure 2A), and a profile of lymphocytic mixed panniculitis with hyaline necrosis of the subcutaneous fat (Figure 2B). Lymphocytic vasculitis (Figure 2C) and fibrin thrombosis (Figure 2D) in the interlobular septa were also observed. These histopathological features are consistent with LEP. Direct immunofluorescence findings (DIF) showed positive IgM deposition in the basement membrane. Immunohistochemistry showed infiltrating lymphocytes were positive for cluster of differentiation (CD)2, CD3, CD5, CD7, CD4, CD8, and TIA-1; partly positive for CD79 and CD20; negative for CD56 and Epstein–Barr virus; and the positive rate of Ki-67 was 30%. These immunohistochemical results did not indicate tumorous proliferation.

FIGURE 2.

(A) Perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrations from the upper dermis to the deep dermis. (B) A profile of lymphocytic mixed panniculitis with hyaline necrosis (red arrows) of the subcutaneous fat. (C) Lymphocytic vasculitis in the interlobular septa. (D) Fibrin thrombosis in the interlobular septa (red arrows; the area squared in black is magnified at the bottom right). (A, original magnification 40×; B, original magnification 100×; C, original magnification 400×; D, original magnification 100×, hematoxylin-eosin).

The patient was given a diagnosis SLE, based on the classification criteria of the American College of Rheumatology. He was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone 40 mg/d (equal to prednisone 1.5 mg/kg/d) and progressively tapered to oral administration of 24 mg/d. In addition, he received intravenous cyclophosphamide 0.4 g daily for 2-day continuation with a 2-week interval. The ulcers healed and the nodules faded after 2 months (Figure 1B). Repeated tests showed normal CBC and C3, and the ANA titer decreased to 71.7 U/mL.

DISCUSSION

LEP was first described by Kaposi in 188310 and termed lupus erythematosus profundus by Irgang in 1940.11 LEP often manifests as tender subcutaneous nodules and plaques with overlying normal skin, or from conditions ranging from erythematous to those of CCLE (e.g., scaling, follicular plugging, dyspigmentation, telangiectasias, or atrophy).12 The incidence rate of skin ulceration is 28% in all of the LEP patients.4 In histopathology, LEP is a predominantly lymphocytic lobular or mixed panniculitis, with frequent plasma cells and sometimes eosinophils. Lymphoid follicles adjacent to the fibrous septa, sometimes with germinal centers, are present in ∼50% of cases and are considered characteristic of LEP.13 Another distinctive feature is so-called hyaline necrosis of fat, in which fat necrosis eventually becomes hyalinization of adipose lobules. Other features include (1) pathological characteristics of discoid lupus erythematosus; (2) dermo-epidermal changes, such as thickening of the basement membrane; (3) mucin deposition; (4) calcifications; (5) vascular changes such as lymphocytic vasculitis, fibrin thrombosis, and perivascular fibrosis.1–3 Vascular changes will contribute to extensive ischemic of the overlying dermis and fat, leading to subsequent ulceration in some cases. The rate of DIF-positive basement membrane can be from 36% to 90.5%, and ∼27% to 95.4% of patients with LEP have elevated ANA titer.1,3 It is suggested that positive ANA indicates a high probability of systemic involvement in LEP patients.3

The diagnosis of LEP is confirmed by clinicopathologic correlation. The differential diagnosis includes the inflammatory diseases of subcutaneous fat: erythema nodosum and erythema induratum of Bazin. The distinction is based on routine histology, immunofluorescence, and ANA test. The particularly troublesome differential diagnosis is subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL). SPTCL has atypical CD3+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes expressing clonal α/β T-cell receptor and arranged in a rim-like fashion around the individual adipocytes. The absence of plasma cells in SPCTL could distinguish it from LEP.14

The first therapy option of LEP is antimalarials, such as hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine. Systemic corticosteroids are often useful for severe cases accompanied by SLE. Other reported systemic therapies include thalidomide, dapsone, cyclosporine, intravenous immunoglobulins, and rituximab.2

Most LEP patients have a favorable prognosis. As many as 2% to 40.9% of SLE patients manifesting LEP lesions, but LEP is considered to be a marker of a less severe form of SLE.1,5 Reported cases in which LEP lesions occur before SLE are very rare. To the best of our knowledge, only 9 cases have been documented, and thus we conducted a systematic review of the English literature (Table 1).5–9

TABLE 1.

Summary of Clinical Characteristics of 10 SLE Patients Presenting with LEP Initially

In the 9 documented cases and the present, altogether the ratio of male to female is 3:7, which is much higher than the general ratio (1:6) in SLE patients.12 The onset age ranged from 8 to 69 years (average, 27.7 years). The LEP manifestations in these patients were various: subcutaneous nodules were the most common (90%), followed by erythematous plaques (20%) and ulcers (20%), and others included skin hyperpigmentation and atrophy. Most patients had more than one site affected and the frequency of affected sites was as follows: extremities (90%), face (50%), and trunk (30%). The time interval from LEP onset to SLE diagnosis ranged from several weeks to 4 years. Notably, the average interval for patients given systemic treatment for LEP was 23.25 months, which was longer than for the 2 patients given only topical treatment (some weeks and 18 months, respectively). At the period of LEP onset, the ANA test was performed in 6 patients and was positive in 3 of them (50%). But at the SLE activity phase, the rate of ANA-positive test was 85.71% (6/7). Common histopathological features were septal or lobular panniculitis, or both, with predominant lymphocytic inflammation. The previous ulcerated patient reported by Patel and Marfatia9 had histopathological features similar to our patient. Both of them displayed panniculitis with hyaline necrosis of fat and obvious vascular changes in the dermis and subcutis. This supports the link between clinical features and histopathology.

The efficiency of antimalarials therapy to treat LEP and delay the onset of SLE in patients with potential SLE has been demonstrated.15 However, among the 7 patients with therapy data in this review, 4 patients given antimalarials nevertheless finally deteriorated to SLE (57.1%). This may indicate that initial utilization of antimalarials (with or without steroids) may not prevent progression to SLE, but because of the small number of cases, prospective and blinded trials are still needed.

Among the 8 patients with follow-up data, 6 improved after corticosteroid treatment given solely or together with other agents such as hydroxychloroquine, cyclophosphamide, and azathioprine. One patient resisted to cyclophosphamide and methylprednisolone achieved remarkable improvement after anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy. Unfortunately, 1 patient died, and thus the mortality rate was 12.5%.

In summary, the purpose of this report was to draw attention to the fact that LEP may be an initial manifestation of SLE. Patients with LEP, especially in those with positive ANA, should have regular follow-ups, including the observation of symptoms and signs, regular blood tests, and immunologic tests. We suggest that early diagnosis and proper treatment is crucial to improving the prognosis of such patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Doris Wang, Professor K. F. Kang, Department of Dermatology, Huashan Hospital of Fudan University, China, and Miss Selin Ho, Medjaden Bioscience Limited, for their help in revising English grammatical errors in this manuscript. They also thank the patient participating in the present study who provided written permission for publication of this case report.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ANA = antinuclear antibody, CBC = complete blood count, CCLE = chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus, CD = cluster of differentiation, DIF = direct immunofluorescence finding, dsDNA = double-stranded DNA, LEP = lupus erythematosus panniculitis, RNP = ribonucleoprotein, SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus, SPTCL = subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, SSA = anti-Ro, SSB = anti-La.

Y-KZ and FW contributed equally to this work.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arai S, Katsuoka K. Clinical entity of Lupus erythematosus panniculitis/lupus erythematosus profundus. Autoimmun Rev 2009; 8:449–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park HS, Choi JW, Kim BK, et al. Lupus erythematosus panniculitis: clinicopathological, immunophenotypic, and molecular studies. Am J Dermatopathol 2010; 32:24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng PP, Tan SH, Tan T. Lupus erythematosus panniculitis: a clinicopathologic study. Int J Dermatol 2002; 41:488–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martens PB, Moder KG, Ahmed I. Lupus panniculitis: clinical perspectives from a case series. J Rheumatol 1999; 26:68–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diaz-Jouanen E, DeHoratius RJ, Alarcon-Segovia D, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus presenting as panniculitis (lupus profundus). Ann Intern Mes 1975; 82:376–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guissa VR, Trudes G, Jesus AA, et al. Lupus erythematosus panniculitis in children and adolescents. Acta Reumatol Port 2012; 37:82–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ajubi N, Nossent JC. Panniculitis as the first manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus: description of two cases. Neth J Med 1993; 42 (1–2):25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandes S, Santos S, Freitas I, et al. Linear lupus erythematosus profundus as an initial manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus in a child. Pediatr Dermatol 2014; 31:378–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel RM, Marfatia YS. Lupus panniculitis as an initial manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus. Indian J Dermatol 2010; 55:99–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaposi M, ed. Pathologie und Therapie der Hautkrankheiten. Vienna, VIE: Urban & Schwarzenberg; 1883. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irgang S. Lupus erythematosus profundus: report of an example with clinical resemblance to Darier-Roussy sarcoid. Arch Dermat Syph 1940; 44:97–108. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruo V, Hochberg MC, Wallace DJ, Hahn BH. (Eds): The Epidemiology of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Dubois’ Lupus Erythematosus. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massone C, Kodama K, Salmhofer W, et al. Lupus erythematous panniculitis(lupus profundus): clinical, histopathological, and molecular analysis of nine cases. J Cutan Pathol 2005; 32:396–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arps DP, Patel RM. Lupus profundus (panniculitis): a potential mimic of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2013; 137:1211–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Daabil M, Massarotti EM, Fine A, et al. Development of SLE among ‘potential SLE’ patients seen in consultation: long-term follow-up. Int J Clin Pract 2014; 68:1508–1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]