Abstract

The burden of obesity-related asthma among children, particularly among ethnic minorities, necessitates an improved understanding of the underlying disease mechanisms. Although obesity is an independent risk factor for asthma, not all obese children develop asthma. Several recent studies have elucidated mechanisms, including the role of diet, sedentary lifestyle, mechanical fat load, and adiposity-mediated inflammation that may underlie the obese asthma pathophysiology. Here, we review these recent studies and emerging scientific evidence that suggest metabolic dysregulation may play a role in pediatric obesity-related asthma. We also review the genetic and epigenetic factors that may underlie susceptibility to metabolic dysregulation and associated pulmonary morbidity among children. Lastly, we identify knowledge gaps that need further exploration to better define pathways that will allow development of primary preventive strategies for obesity-related asthma in children.

Pediatric obesity is a major public health issue that has reached epidemic proportions, affecting ∼18% of school-going children in the United States.1 Although the overall prevalence of pediatric obesity has increased, prevalence rates differ by age, gender, and ethnicity1 and are partly determined by sociodemographic factors.2 Notably, obesity is more prevalent among Hispanic and African American children than their non-Hispanic white counterparts.1

Asthma, another chronic pediatric disease with increasing prevalence over the past 3 decades, affects ∼10% of all school-age children in the United States.3 Racial and ethnic differences evident in the prevalence of obesity overlap with those of asthma; namely, asthma is more common among African Americans and Hispanics, particularly Puerto Ricans, compared with non-Hispanic white children.3 The increase in asthma prevalence is likely multifactorial, ranging from environmental factors including early-life exposures to allergens to caregiver issues including low caregiver asthma management self-efficacy and empowerment.4 Similar environmental factors including increased built area with decreased outdoor play, increased screen time, increased intake of high-calorie foods, and caregiver food choices play a role in high childhood obesity prevalence.5

Over the past decade, many cross-sectional and prospective epidemiologic studies have found an association between pediatric obesity and asthma.6–12 A recent meta-analysis, including 6 prospective cohort studies on the effect of body weight on future risk of asthma, found a twofold increased risk in obese children compared with normal-weight children,12 suggesting that obesity is an independent risk factor for childhood asthma.12 Clinical studies also suggest that obesity-related asthma is distinct from normal-weight asthma. Obesity-related asthma is associated with decreased medication responsiveness13 and poor disease control,14–16 particularly among ethnic minority children,14,15 contributing to increased health care expenditure. However, the mechanisms that underlie these epidemiologic and clinical associations are poorly understood, and this gap precludes scientific advancement toward development of targeted therapies. Here, we review recent scientific studies that begin to elucidate the potential role of metabolic dysregulation and its associated inflammation in pediatric obesity-related asthma. It is important to note that although the majority of studies included in this review defined obesity as BMI >95th percentile, some combined current definitions of overweight and obese (BMI >85th percentile). Moreover, this review focuses on mechanisms underlying obesity-related asthma, rather than incident obesity among children with asthma.

Mechanisms Linking Obesity and Asthma

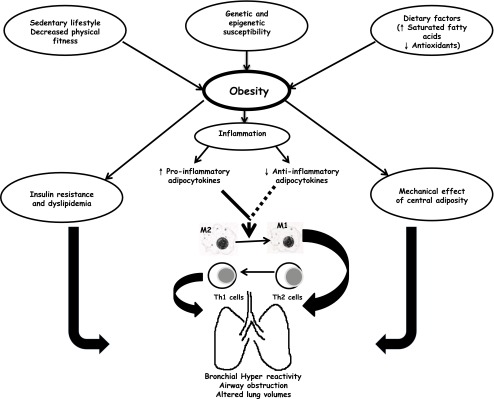

Many mechanisms may underlie the obesity-asthma association (Fig 1). They range from obesity-mediated alteration of pulmonary function, due to the mechanical truncal fat load and/or inflammation,17 alteration in macro- and micronutrient intake,18 and a sedentary lifestyle and its associated obesogenic behaviors.19 Furthermore, immunomodulatory effects of obesity, mediated by adipocytokines including leptin, have also been postulated to underlie asthma in obese children.20,21 However, because not all obese children develop asthma, these factors may play a role, but do not explain the higher predisposition for pulmonary morbidity in some, but not other, obese children. Therefore, there is need for better identification of key molecules and biomarkers that may predict asthma development among at-risk obese children.

FIGURE 1.

Mechanisms proposed to underlie pediatric obesity-related asthma. This figure summarizes the factors associated with obesity-related asthma in the context of obesity preceding asthma. Although several factors such as genetics and epigenetics are also associated with childhood asthma, the relationships shown in this figure are specific to those discussed in this review.

Recently, asthma has been associated with insulin resistance,22 dyslipidemia,23,24 and metabolic syndrome,25 measures of metabolic dysregulation that develop in some but not all obese children.26,27 Moreover, genetic and epigenetic differences in molecules involved in metabolic dysregulation and its associated inflammation have been found in the context of obesity-related asthma. In this review, we initially summarize the better-investigated mechanisms such as the mechanical effect of truncal adiposity on pulmonary function and the association of sedentary lifestyle and dietary intake with obesity-related asthma. We then discuss more recent literature on the association of obesity-mediated inflammation and metabolic dysregulation with pediatric obesity-related asthma and its genetic and epigenetic footprint (Fig 1), which together begin to identify key molecules that likely underlie the complex pathophysiology of obesity-related asthma.

Mechanical Effect of Obesity on Pulmonary Mechanics and Asthma

Obesity, and its related measure, truncal adiposity,28–30 have been associated with asthma,29–31 and pulmonary function deficits,28 including among ethnic minority children30,32 (Table 1). Excess truncal adiposity renders a mechanical disadvantage to the diaphragm due to mechanical fat load and is associated with decreased functional residual capacity (FRC),33–35 with reduced residual volume (RV) and expiratory reserve volume (ERV).33–37 Lower FRC influences bronchial smooth muscle stretch, especially at the end of tidal volume exhalation, which leads to perception of increased respiratory effort with normal inspiration.38 Although obese children have higher forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC)39,40 than normal-weight children, the combination of mechanical restriction and low lung volumes predispose obese children to present with lower FEV1/FVC ratio,33 reduced even compared with their normal-weight counterparts32,39,41 (Table 1). However, unlike normal-weight asthma, obese asthmatic children have reduced FRC with low lung volumes.33

TABLE 1.

Summary of Pediatric Studies Reporting an Association Between General or Truncal Adiposity and Asthma

| Study | Study Design | Obesity Definition/ BMI Analysis | Sample Size, n | Age, y, (Range/Mean ± SD) | Ethnicity | Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tantisira et al, 200339 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 1041 | 5–12 | Whites (17%), Blacks (17.6%), Hispanic (18.8%) Others (16.6%) | Decrease in FEV1/FVC ratio was associated with increase in BMI. |

| Perez-Padilla et al, 200642 | CS | BMI >95th percentile or BMI above limits set by International Obesity Task Force | 6784 | 8–20 | Mexican | Increase in FEV1 and FVC but decrease in FEV1/FVC ratio with increase in BMI. Increase more in preadolescents than adolescents. |

| Chu et al, 200940 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 14 654 | 14.3 ± 0.9 | Taiwanese | Higher FEV1 and FVC but lower FEV1/FVC ratio with higher BMI. |

| Musaad et al, 200928 | CS | BMI >85th percentile for age and gender | 1123 | 5–18 | Caucasian (57.4%), African American (33.8%), others (8.8%) | BMI and waist circumference were inversely associated with FEV1. |

| Spathopoulos et al, 200941 | CS | BM I>95th percentile for age and gender | 2715 | 6–11 | Caucasian (Greek) | High BMI is inversely correlated with FEV1, FVC, FEV1/FVC ratio, and FEF25%–75%. |

| Chen et al, 200943 | CS | BMI analyzed as a continuous variable | 718 | 6–17 | Caucasian (Canadian) | Waist circumference was inversely associated with FEV1/FVC. |

| Consilvio et al, 201044 | CS | BMI >2 SD for age and gender | 118 | 6–9 | Caucasian (Italian) | Obese asthmatic children had low FEV1/FVC ratio. |

| Sidoroff et al, 201145 | L | BMI >98th percentile for age and gender | 100 | 4–12 | Caucasian (Finnish) | Weight gain associated with decrease in FEV1/FVC ratio. |

| Huang et al, 201246 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 140 | 10–16 | Mexican | No association between FEV1/FVC ratio and BMI in asthmatics. |

| Rastogi et al, 201233 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 120 | 7–11 | African Americans (50%), Hispanics (50%) | FEV1/FVC ratio, and FEF25%–75% was lower in obese asthmatics |

| Vo et al, 201332 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 980 | 7–20 | Whites (16%), African Americans (42%), and Hispanics (42%) | Higher FEV1 and FVC but decrease in FEV1/FVC ratio with higher BMI. FEV1/FVC ratio was lower in overweight and obese African Americans and Hispanics, and obese Whites. |

| Jensen et al, 201347 | CS | BMI z score >1.64 SD | 361 | 8–17 | Caucasian (Australian) | Lung volumes reduced among obese children; ERV reduced in obese asthmatics, RV and RV/TLC ratio reduced in obese nonasthmatic children. |

| Jensen et al, 2014 48 | CS | BMI z score analyzed as a continuous variable | 48 | 11.9 ± 2.3 (Boys) 13.6 ± 2.2 (Girls) | Caucasian (Australian) | Lean mass, not fat mass, is associated with FEV1, FVC, and TLC in boys and with TLC in girls. |

| Sanchez-Jimenez et al, 201449 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 153 | 4–15 | Caucasian (Spanish) | Waist circumference was inversely associated with FEV1 and FVC. |

| Wang et al, 201450 | CS | BMI z score analyzed as a continuous variable | 646 | 11–12 | Caucasian (British) | Higher FEV1 and FVC with higher BMI in girls. Percent truncal fat inversely correlated with FEV1 and FVC in boys but not girls. |

| Rastogi et al, 201434 | CS | BMI >95th percentile | 168 | 13–18 | African Americans (42.1%), Hispanics (57.9%) | Truncal adiposity and general adiposity were associated with reduced FRC, RV, and RV/TLC ratio. |

CS, cross-sectional; L, longitudinal.

These studies suggest an association among truncal adiposity, asthma, and altered lung mechanics. However, because truncal adiposity is a risk factor for metabolic dysregulation,51 we speculate that metabolic dysregulation, not investigated in these earlier studies, may have coexisted with truncal adiposity. In keeping with this speculation, insulin resistance and dyslipidemia were found to be predictors of FEV1/FVC ratio and ERV,34 the 2 pulmonary function indices that are decreased among obese asthmatics, and mediated the association of BMI and waist circumference with these indices,34 suggesting that biological factors other than mechanical fat load may mediate the influence of obesity on pulmonary function.

Ethnicity and gender may also influence these associations. Hispanics and African Americans, who bear a higher burden of obesity-related asthma, have greater truncal adiposity for the same body weight than Caucasians.52 With regard to gender, although obese girls have more symptoms53,54 and nonatopic inflammation compared with boys,47 boys have a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome.25 Moreover, whereas one study reported an association between truncal fat and FEV1 and FVC only among boys,50 another study found an association between lean mass, rather than fat mass, with FEV1, FVC, and total lung capacity (TLC) among boys, and only with TLC in girls.48 The disparate results of these few studies highlight the need for gender as well as ethnicity-specific investigations of the associations among mechanical fat load, presence of metabolic dysregulation, and pulmonary function deficits linked with pediatric obesity-related asthma.

Weight Loss

Thus far, there are only 2 studies on the effect of weight loss on obesity-related asthma in children.48,55 Jensen et al reported an improvement in asthma control in obese asthmatics following diet-induced weight loss.48 ERV and RV/TLC ratio and Pediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (PAQLQ) symptom and emotional domain scores also improved but did not differ significantly from the change in the control group.48 Van Leeuwen et al reported decreased severity of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction and improved PAQLQ scores, particularly in the symptoms and activity domain, after weight loss.55 Moreover, limiting caloric intake in the normal range in obese children was also associated with improvement in asthma control and PAQLQ scores.56 Together, this limited literature suggests that weight loss in children is associated with improvement in clinical and quality-of-life parameters. However, there are no studies on pulmonary effects of weight loss in ethnic minority children. Because diet-induced weight loss in children, particularly among those of minority ethnic background, is often modest,57 other therapeutic options are needed to address obesity-mediated pulmonary morbidity in the pediatric populations most afflicted by these diseases.

Diet and Asthma

Increased intake of processed food, high in fat and low in antioxidant content, has been associated with asthma.58,59 Conversely, consumption of the Mediterranean diet, high in fruits and vegetables, and omega-3 fatty acids, has been found to be protective.60–63 Therefore, the type of fat, in addition to total fat intake, may play a role in its association with asthma. Systemic inflammation linked to dietary fat intake may underlie these associations.64–66 Omega-6 fatty acids, including arachidonic acid (20:4 n-6) and linoleic acid (18:2 n-6), mediate inflammation,67 whereas omega-3 fatty acids, including eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5 n-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (22:6 n-3), are protective.67,68 Prostaglandins and leukotrienes, both of which are arachidonic acid metabolites, have been quantified in exhaled breath condensates from children with asthma.69 However, the extent to which asthma symptomatology and pulmonary function improve with increased intake of omega-3 or decreased intake of omega-6 fatty acids is not well known among obese children with asthma and is being investigated in ongoing randomized trials of omega-3 fatty acids supplementation.70

Furthermore, intake of micronutrients such as vitamins A,59,71,72 C,59,73 and E73 has been inversely associated with asthma, whereas vitamin D insufficiency has been associated with higher asthma disease burden74 and lower lung function.75,76 Although the exact mechanism through which vitamin D influences asthma in obese children is not known, vitamin D does have immunomodulatory effects77 and may influence intestinal microflora,78 mechanisms that have been associated with asthma pathophysiology.79,80 There is also evidence to suggest that maternal diet may influence incident childhood asthma and obesity, an aspect that has been previously reviewed.81 Although these initial studies suggest that dietary intake may be linked to obesity-related asthma, more research is needed to explore the various effects of dietary macro- and micronutrients on asthma.

There is also a substantive role of parental choice82 and feeding practices83 in a child’s dietary intake82 and behavior,83 including among Hispanics84,85 and African Americans.86 For example, among Hispanic households, >50% of the parents reported having sugar-sweetened beverages, and >80% reported having energy-dense foods including potato chips, cookies, cake, or ice cream in their home.84 In keeping with these findings, weight-resilient African American adolescents were those who consumed more fruits and vegetables and whose parents were in the healthy weight range and provided supervision to physical activity and accessed grocery stores with better food availability.86 Given the complex relationships between macro- and micronutrient intake and asthma and the role of parental dietary choices and feeding practices on dietary intake, future studies are needed to define the impact of each of these aspects of nutritional intake on childhood asthma, including obesity-related asthma. These findings may elucidate a role of dietary modification rather than restriction in the management of obesity-related asthma,18,87 particularly in those of minority ethnicities, given their higher disease burden and modest effectiveness of weight loss.

Sedentary Lifestyle, Physical Fitness, and Asthma

Obese children also tend to have a sedentary lifestyle. Increased use of electronic gadgets, television watching, and video games has decreased outdoor play time and been linked with overweight and obesity in children.88,89 The number of hours playing video games and watching TV directly correlate with asthma incidence and prevalence among children.19,90 Sedentary lifestyle and decreased physical fitness cause central obesity and thereby predispose children to asthma.91,92 Moreover, the association of functional exercise capacity among obese asthmatics with BMI and not with FEV1/FVC ratio, suggests a larger role of adiposity in exercise limitation among obese asthmatics.93 Together these associations highlight the importance of addressing such obesogenic behaviors early in life to prevent the development of obesity and its associated pulmonary morbidities.

Obesity-Mediated Inflammation and Asthma

Obesity is recognized to be a low-grade inflammatory state. Obesity-mediated inflammation has been associated with asthma and pulmonary function deficits.33 Adipocyte hypoxia due to delayed neovascularization of adipose tissue is the most potent known stimulus for initiation of adipose tissue inflammation94 and release of leptin, a proinflammatory adipokine. The proinflammatory cascade comprises a shift in the macrophage pool from the antiinflammatory M2 macrophages to the proinflammatory M1 macrophages (Fig 1).95 Additionally, there is enhanced CD4+ T lymphocyte proliferation and differentiation into Th1 cells (Fig 1), with increased interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin (IL)-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) production.95 This correlates with suppression of Th2 cells and decrease in T regulatory cells.96 To maintain homeostasis, the proinflammatory effect of leptin is offset by antiinflammatory adipokines, including adiponectin, and omentin and the related antiinflammatory cytokine IL-10.97–99

Clinical studies have demonstrated elevated leptin21 and reduced adiponectin levels in obese children33,100 compared with nonobese children with asthma, suggesting that obesity-induced changes in the systemic adipocytokine milieu may underlie asthma in children.101 Serum leptin levels correlate with higher Th1/Th2 cell ratio,33,102 and higher serum IFN-γ levels,21 indicative of nonatopic inflammation among obese asthmatic children compared with their nonobese counterparts, including in ethnic minority children.33,103 These nonatopic systemic inflammatory patterns correlate with lower airway obstruction33 and exercise-induced bronchoconstriction104 among obese asthmatic children and persist into adulthood.105 These findings support epidemiologic reports of a lack of association between childhood obesity-related asthma and atopy7,101,106 and higher prevalence of noneosinophilic asthma in obese children.47 However, there are also reports of increased atopy among obese children,53,54,107 including associations among BMI, atopic sensitization, and bronchial hyperresponsiveness,53 as well as among BMI, atopy, cough, and wheeze,54 particularly among girls53,54 (Table 2). Similar disparate links among obesity, asthma, and atopy are also observed in investigations of allergic airway inflammation using fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) and obesity-related asthma. Whereas BMI was associated with asthma only among children with low FeNO,108 BMI was associated with higher asthma disease burden among those with high FeNO108 (Table 2). Furthermore, FeNO was not associated with asthma among obese children,109 and a significant association between BMI and FeNO was observed only among nonasthmatic children.110

TABLE 2.

Summary of Pediatric Studies Reporting an Association Between Inflammatory Mediators of Obesity and Asthma

| Study | Study Design | Obesity Definition/ BMI Analysis | Sample Size, n | Age Range, y | Ethnicity | Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huang et al, 199953 | CS | BMI analyzed in quintiles | 1459 | 13.2–15.5 | Taiwanese | BMI was a significant predictor of atopy, allergic symptoms, and airway hyperresponsiveness in teenage girls. |

| Von Mutius et al, 20017 | CS | BMI analyzed in quartiles | 7370 | 4–17 | Caucasians (26.3%), African Americans (34%), Mexican Americans (35%), others (4.8%) | BMI is associated with asthma, but not with atopy, among children sampled in NHANES III. |

| Schachter et al, 200354 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 5993 | 7–12 | Caucasian | Higher BMI is a risk factor for atopy, wheeze and cough in girls only but not a risk factor for asthma or airway hyperresponsiveness in either boys or girls. |

| Leung et al, 2004111 | CS | Body wt >120% of the median wt for height | 115 | 7–18 | Hong Kong | Obesity is not associated with FeNO or airway leukotriene levels in asthmatic children |

| Santamaria et al, 2007109 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 50 | 8–16 | Caucasian (Italian) | No association between FeNO and obesity among asthmatic children. |

| Huang et al, 2008112 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 89 | 10–16 | Mexican | Higher markers of endothelial inflammation (sICAM) among obese asthmatics. No difference in CRP levels between obese and normal-weight asthmatic children. |

| Michelson et al, 2009113 | CS | BMI z score analyzed as a continuous variable | 10 140 | 0–19 | Caucasians (60.6%), African Americans (14.4%), Mexicans (12.4%), other Hispanics (6.4%), others (6.3%) | BMI z score and CRP levels were associated with asthma severity among children in NHANES 2001–2004. |

| Visness et al, 2010106 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 16 074 | 2–19 | Caucasians (59.9%), African Americans (14.7%), Mexicans (12.5%), others (12.9%) | Association between obesity and asthma greater among non-atopic children than atopic children. Association of CRP with asthma among nonatopics mediated by BMI. |

| Rastogi et al, 201233 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 120 | 7–11 | African Americans (50%), Hispanics (50%) | Obese asthmatics had systemic Th1 polarization, which directly correlated with lower airway obstruction. |

| Huang et al, 201246 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 178 | 10–16 | Mexican | Obese asthmatics and nonasthmatics had higher plasminogen activator inhibitor, fibrinogen, and BMI with inversely correlated with FEV1/FVC ratio. |

| Khan et al, 2012114 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 124 | 12–20 | African Americans (41%), Hispanics (59%) | hsCRP highest in obese asthmatics compared with obese nonasthmatics, normal-weight asthmatics, and healthy controls |

| Sah PK et al, 2013115 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 269 | 6–17 | Whites (32.7%), nonwhites (67.3%) | Obese asthmatics with poor asthma control had lower serum levels of IL-5, IL-13, and IL-10. |

| Youssef et al, 2013102 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 70 | 9.3 ± 2.5 (obese asthmatics) 10.4 ± 1.3 (nonobese asthmatics) 10.7 ± 2.9 (controls) | Caucasian (Egyptian) | Obese asthmatics had high asthma severity, lower FEV1. Serum leptin levels correlated with serum IFNγ levels, which directly correlated with asthma symptoms and inversely correlated with FEV1 among obese asthmatic children. |

| Jensen et al, 201347 | CS | BMI z score >1.64 SD | 361 | 8–17 | Caucasian (Australian) | Noneosinophilic asthma more prevalent in obese asthmatic girls than boys. |

| Han et al, 2014108 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 2681 | 6–17 | Caucasians (33.3%), African Americans (20.2%), Hispanics (40.2%), others (5.7%) | Adiposity indicators are associated with asthma among children with low FeNO. Adiposity indicators are associated with worse asthma morbidity in those with high FeNO among children in NHANES 2007–2010. |

| Rastogi et al, 2015103 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 168 | 13–18 | African Americans (42.1%), Hispanics (57.9%) | Th1 polarization and monocyte activation correlated with metabolic abnormalities in obese asthmatics. Association of monocyte activation with pulmonary function was mediated by BMI, whereas that of Th1 polarization was mediated by insulin resistance. |

CRP, C-reactive protein; CS, cross-sectional; HsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

It is hypothesized that these disparate reports either support heterogeneity in the pathophysiology of obesity-related asthma116 or are reflective of inherent differences in disease severity.108 As noted in normal-weight asthma, although classic asthma is atopic, involving eosinophils and Th2 cells, severe asthma, even among normal-weight individuals, is nonatopic, mediated by neutrophils.117 Whether similar variability in the involvement of innate immune pathways comprising Th1 cells, M1 macrophages, and neutrophils occurs in the pathogenesis of obesity-related asthma needs further investigation. Recent literature highlighting the role of metabolic dysregulation in obesity-related asthma118 may begin to clarify these issues because differential inflammation among obese individuals with or without metabolic dysregulation may partly underlie the heterogeneity of the obese asthma phenotype.

Obese asthmatics are also less responsive to steroid treatments.13,119 Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from obese asthmatics had lower production of antiinflammatory enzymes in response to dexamethasone,119 and increased TNF production, which directly correlated with BMI.119 Similar trends were also observed in bronchoalveolar lavage cells obtained from obese asthmatics.119 On the basis of these reports, it can be speculated that obese asthmatics may respond to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents including montelukast or etanercept, a TNF inhibitor,120,121 an aspect that needs further investigation.

Obesity-Mediated Metabolic Dysregulation and Asthma

Association With Insulin Resistance

Obese children, particularly those of ethnic minorities, are predisposed to develop insulin resistance,122 a precursor to diabetes,123 that is associated with systemic hyperinsulinemia.122 Our review of the recent literature highlights that metabolic dysregulation plays a role in pediatric obesity-related asthma (Table 3). Higher prevalence124 and degree of insulin resistance22 and higher prevalence of its surrogate marker, acanthosis nigricans,23 and metabolic syndrome,25 have been reported among children with asthma compared with their nonasthmatic counterparts. Insulin resistance correlates with the proinflammatory markers leptin and IL-6124 and is found to be a predictor of both lower airway obstruction and reduced lung volumes, 2 distinct measures of lung function deficits, independent of general and truncal adiposity.34

TABLE 3.

Summary of Pediatric Studies Reporting an Association Between Metabolic Dysregulation and Asthma

| Study | Study Design | Obesity Definition | Sample Size, n | Age, y (Range/Mean ± SD) | Ethnicity | Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Shawwa, et al, 200624 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 188 | 4–20 | Not available | Hypercholesterolemia is associated with higher asthma frequency, independent of obesity. |

| Al-Shawwa et al, 200722 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 415 | 2–18 | Caucasian (40.5%), African Americans (38.5%), others (21%) | Obese asthmatics had higher levels of insulin resistance compared with morbidly obese nonasthmatics. Asthma prevalence directly correlated with insulin levels. |

| Arshi et al, 2010124 | CS | BMI analyzed as a continuous variable | 31 | 6–17.9 | Caucasian (Australian) | Insulin resistance was present among atopic asthmatics, which correlated with leptin and IL-6 levels. |

| Del-Rio-Navarro et al, 201025 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 443 | 12–14.2 | Mexican | Prevalence of metabolic syndrome was higher among obese asthmatic boys, not girls. |

| Cottrell et al, 201123 | CS | BMI >95th–98.9th percentile for age and gender | 17 994 | 4–12 | Whites (90.7%), African American (2.3%), others (0.9%) | Asthma is associated with dyslipidemia and insulin resistance, independent of BMI. |

| Lee et al, 201258 | CS | BMI analyzed as a continuous variable | 2082 | 8.5 ± 1.7 | Taiwanese | Diet with high intake of fat and simple sugars was associated with increased risk of asthma. |

| Chen et al, 2013125 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 462 | 10–15 | Taiwanese | Asthma was associated with higher levels of total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein, particularly in overweight and obese children. |

| Rastogi et al, 201434 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 168 | 13–18 | African Americans (42.1%), Hispanics (57.9%) | Dyslipidemia and insulin resistance were predictors of pulmonary function deficits, independent of adiposity |

| Sanchez-Jimenez et al, 201449 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 153 | 4–15 | Caucasian (Spanish) | Insulin levels were associated with allergen sensitization among asthmatics. |

| Rastogi et al, 2015103 | CS | BMI >95th percentile for age and gender | 168 | 13–18 | African Americans (42.1%), Hispanics (57.9%) | Th1 polarization and monocyte activation correlated with metabolic abnormalities. Insulin resistance mediated the association of Th1 polarization with pulmonary function. |

CS, cross-sectional.

Systemic inflammation, associated with insulin resistance, may be one of the mechanisms through which insulin resistance contributes to impaired lung function and asthma phenotype. In addition to its role in glucose metabolism, insulin has antiinflammatory effects.126 Insulin supplementation has been associated with attenuation of lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in a murine model, with decreased TNF, IL-1β, and IL-6 in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.127 Obesity-mediated inhibition of insulin signaling, a key mechanism underlying insulin resistance, is associated with adipose tissue inflammation with activation of Th1 cells and innate immune pathways, involving macrophages.128 Recent studies have found that insulin resistance mediates the association of systemic Th1 polarization with obesity-mediated pulmonary function deficits among ethnic minority children.103 Given these initial investigations into the association among insulin resistance, inflammation, and pulmonary function impairment, further study of the underlying immunometabolic pathways is needed to determine the mechanism through which insulin resistance contributes to the obese asthma phenotype.

Another mechanism is the influence of insulin on airway smooth muscle (ASM). Insulin resistance is associated with airway hyperreactivity due to increased ASM contractility.129 Several mechanisms underlie this observation. Hyperinsulinemia increases laminin expression in bovine ASM cells via phospho-inositide-3 kinase (PI3K)/Akt dependent pathway.129 Insulin resistance also increases free insulin-like growth factor, which is associated with ASM proliferation.130 Furthermore, insulin may increase airway hyperresponsiveness by modulating parasympathetic stimulation, studied in an obese rat model.131 These studies suggest that insulin resistance and associated hyperinsulinemia influence ASM cell function through different mechanisms, with the end result of increased bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Translational studies are now needed to study the role of each of these pathways in ASM cells obtained from obese asthmatics. We believe that better understanding of these pathways will be paradigm changing by potentially extending the use of metformin, routinely prescribed for insulin resistance, into management of obesity-related asthma.132

Association With Dyslipidemia

Similar to insulin resistance, links have been described between dyslipidemia and wheezing in adults133 and asthma among children23 (Table 3). High-density lipoprotein (HDL) has been found to have a protective effect on pulmonary function indices in obese urban adolescents.34 There is preliminary evidence to suggest that this effect may be mediated in part by the protective effect of HDL on monocyte activation.103 There is also increasing evidence to suggest that the origins of the association of diet-induced metabolic dysregulation and pulmonary morbidity may start as early as in utero. For instance, altered fat intake, with low intake of poly-unsaturated fatty acids in the mother, has been associated with an increased predisposition to asthma among the offspring.134 Thus, altered fat intake and dyslipidemia, irrespective of BMI, may be risk factors for airway inflammation and hyperreactive airways.23

Many mechanisms, including inflammation, may underlie the association between dyslipidemia and asthma. High fat intake in an adult cohort was associated with increased neutrophilic airway inflammation and an attenuated response to bronchodilators.135 Similarly, a high-fat meal, associated with elevated triglycerides and reduced HDL after 2 hours, correlated with increased levels of FeNO.136 Because high-fat diet is associated with decreased consumption of antioxidants, it may make the lung susceptible for oxidative damage and inflammation.18 These pathways have not been studied in children, and thus the mechanisms underlying the association of dyslipidemia with asthma in children are relatively unknown.

Crosstalk Between Genes and Environment in Obesity-Related Asthma

The associations of asthma with obesogenic lifestyles and obesity-mediated metabolic dysregulation, inflammation, and mechanical fat load suggest that these environmentally mediated exposures and clinical states may influence the lungs via epigenetic mechanisms.137,138 However, it is also evident that not all obese children with metabolic dysregulation or inflammation develop asthma, suggesting that differences in genetic susceptibility may also underlie the development of pulmonary morbidity in only some obese children. Although few studies have investigated the genetics or epigenetics of obesity-related asthma, we discuss the existing literature and the direction of association observed in these initial investigations.

Epigenetics of Obesity-Related Asthma

Epigenetic differences have been identified in context of both obesity139,140 and asthma141,142 compared with healthy controls. Among obese children, differences in DNA methylation, an epigenetic regulatory mechanism, were identified at 5 sites at the FTO gene, variants of which are strongly associated with obesity.139 Similarly, hypomethylation of DNA at the IL-4 gene promoter and hypermethylation of the IFNγ promoter have been observed in children with atopic asthma.143 Genome-wide studies have also identified differential methylation of several genes associated with atopic inflammation among asthmatics.141 However, only 1 study defined differences in DNA methylation among children with obesity-related asthma compared with children with normal-weight asthma, obesity without asthma, and healthy controls.144 In this study, specific DNA methylation patterns were associated with childhood obesity-related asthma. Gene promoters encoding for molecules involved in Th1 polarization, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 (CCL5), interleukin 2 receptor α chain (IL2RA), and T-box transcription factor (TBX21), were hypomethylated, whereas those encoding for receptors for immunoglobulin E and TGFB1, involved in Th1 cell inhibition, were hypermethylated,144 suggesting DNA methylation plays a role in Th1 polarized systemic inflammation. Additionally, molecules such as PI3K and PPARγ, involved in glucose metabolism in T cells,145 and lipid uptake, respectively, were hypomethylated in obese asthmatics relative to obese nonasthmatics. These findings suggest that molecules associated with both inflammation and metabolic dysregulation are differentially methylated among obese asthmatics. Because dietary intake and nutrients modify DNA methylation,138 these pilot results highlight the need for additional studies to investigate the effect of diet modification and related weight loss on DNA methylation and its association with insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and systemic inflammation among obese asthmatics.

Genetics of Obesity-Related Asthma

While few conclusive studies have identified susceptibility loci for development of asthma among obese children,146 a common 16p11.2 inversion that may protect against susceptibility to asthma and obesity has been identified in adults.147 This inversion, found in 10% of Africans and ∼50% of Europeans, is associated with increased expression of obesity-associated proteins including apolipoprotein B (APOB48R) and SH2B1, which inhibit type 1 interferon and IL27. This inversion explains ∼40% of the population-attributable risk for joint susceptibility to obesity and asthma. Additional genes including the β2-adrenergic receptor gene (ADRB2),148,149 the TNF gene,150,151 and the lymphotoxin-α (LTA) gene152,153 have been associated in both obesity and asthma in children. However, the limited number of these studies highlights the paucity of data on genetic susceptibility for obesity-related asthma. Moreover, given the ethnic differences in the prevalence of pediatric obesity-related asthma, studies are needed to identify the role, if any, of ancestry-specific genetic polymorphisms that may explain the greater disease burden among Hispanics and African Americans.

Recommendations for Clinical Practice

Together, these studies on the mechanisms underlying obesity-related asthma suggest a complex interplay among mechanical fat load of truncal adiposity, metabolic dysregulation, and inflammation. On the basis of these studies, we suggest that pediatricians consider implementing the following in their clinical practice:

Routine evaluation for truncal adiposity by measuring waist circumference among their patients who are overweight/obese

Routine evaluation for metabolic dysregulation, specifically for insulin resistance and dyslipidemia in fasting blood among obese children,154 particularly in those with truncal adiposity

Elucidation of respiratory symptoms among obese children, particularly those with truncal adiposity, and/or metabolic dysregulation

Testing for pulmonary function deficits among obese children, especially those with truncal adiposity, and/or metabolic dysregulation

Ensure good asthma control and encourage physical activity for weight control because there is no therapy specific for obesity-related asthma, and these children are suboptimally responsive to inhaled steroids

Encourage parents to monitor dietary intake, with increased intake of foods included in a Mediterranean diet and decreased consumption of processed foods

Road Map for Future

In summary, obesity-related asthma is an emerging health problem among children. Although it appears to be distinct from normal-weight asthma, further investigations are needed to better define its pathophysiology. The association of obesity-related asthma with insulin resistance and dyslipidemia provides directionality to future investigations into underlying pathways that may be amenable to pharmacologic modification. Because these metabolic abnormalities are obesity-mediated but do not develop in all obese children, quantification of these metabolic biomarkers may help identify obese children at risk for developing obesity-mediated pulmonary morbidity. Moreover, the association of asthma with diet, particularly fat and vitamin intake, and the association of diet with DNA methylation highlights the need for studies to better define the links between diet and epigenetics of obesity-related asthma, in the presence of insulin resistance and/or dyslipidemia. Given the modest effect of weight loss interventions among children and lack of studies on the pulmonary effects of bariatric surgery, these future studies will identify mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of nutrients and thereby facilitate the development of targeted diets for obese children at risk for developing obesity-related asthma, specifically those of Hispanic and African American ancestry. Identification of ancestry-specific genetic susceptibility will not only shed light on the reasons underlying increased disease burden among certain populations but may facilitate the development of primary prevention strategies for those identified to be genetically susceptible to obesity and its associated morbidities. Because obese asthmatics are suboptimally responsive to current asthma medications, identification of mechanisms underlying obesity-related asthma will provide direction for development of both preventative strategies and targeted therapy.

Glossary

- ASM

airway smooth muscle

- ERV

expiratory reserve volume

- FeNO

fractional exhaled nitric oxide

- FEV1

forced expiratory volume in 1 second

- FRC

functional residual capacity

- FVC

forced vital capacity

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- IL

interleukin

- PAQLQ

Pediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire

- RV

residual volume

- Th cells

T helper cells

- TLC

total lung capacity

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

Footnotes

Dr Vijayakanthi performed literature searches on the topic and subtopics for relevant articles for inclusion and drafted and edited the manuscript; Dr Greally conceptualized the manuscript with Mr Rastogi and critically reviewed the manuscript; Mr Rastogi conceptualized the manuscript with Dr Greally, performed literature searches on the topic and subtopics for relevant articles for inclusion in the manuscript, and edited the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Dr Rastogi (K23HL118773) and Dr Greally (R01DA030317 and R21GM101880) are supported by the National Institutes of Health. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):483–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossen LM, Talih M. Social determinants of disparities in weight among US children and adolescents. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24(10):705–713.e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Garbe PL, Sondik EJ Status of childhood asthma in the United States, 1980–2007. Pediatrics 2009;123 (suppl 3):S131–145 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Canino G, Vila D, Normand SL, et al. Reducing asthma health disparities in poor Puerto Rican children: the effectiveness of a culturally tailored family intervention. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(3):665–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dixon B, Peña MM, Taveras EM. Lifecourse approach to racial/ethnic disparities in childhood obesity. Adv Nutr. 2012;3(1):73–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Figueroa-Muñoz JI, Chinn S, Rona RJ. Association between obesity and asthma in 4–11 year old children in the UK. Thorax. 2001;56(2):133–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von Mutius E, Schwartz J, Neas LM, Dockery D, Weiss ST. Relation of body mass index to asthma and atopy in children: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Study III. Thorax. 2001;56(11):835–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gold DR, Damokosh AI, Dockery DW, Berkey CS. Body-mass index as a predictor of incident asthma in a prospective cohort of children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003;36(6):514–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Marcos L, Arnedo Pena A, Busquets-Monge R, et al. How the presence of rhinoconjunctivitis and the severity of asthma modify the relationship between obesity and asthma in children 6–7 years old. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38(7):1174–1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flaherman V, Rutherford GW. A meta-analysis of the effect of high weight on asthma. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(4):334–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rzehak P, Wijga AH, Keil T, et al. ; GA²LEN-WP 1.5 Birth Cohorts . Body mass index trajectory classes and incident asthma in childhood: results from 8 European Birth Cohorts—a Global Allergy and Asthma European Network initiative. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(6):1528–1536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen YC, Dong GH, Lin KC, Lee YL. Gender difference of childhood overweight and obesity in predicting the risk of incident asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2013;14(3):222–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forno E, Lescher R, Strunk R, Weiss S, Fuhlbrigge A, Celedón JC; Childhood Asthma Management Program Research Group . Decreased response to inhaled steroids in overweight and obese asthmatic children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(3):741–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belamarich PF, Luder E, Kattan M, et al. Do obese inner-city children with asthma have more symptoms than nonobese children with asthma? Pediatrics. 2000;106(6):1436–1441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kattan M, Kumar R, Bloomberg GR, et al. Asthma control, adiposity, and adipokines among inner-city adolescents. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(3):584–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quinto KB, Zuraw BL, Poon KY, Chen W, Schatz M, Christiansen SC. The association of obesity and asthma severity and control in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(5):964–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dixon AE, Holguin F, Sood A, et al. ; American Thoracic Society Ad Hoc Subcommittee on Obesity and Lung Disease . An official American Thoracic Society Workshop report: obesity and asthma. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7(5):325–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wood LG, Gibson PG. Dietary factors lead to innate immune activation in asthma. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;123(1):37–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corbo GM, Forastiere F, De Sario M, et al. ; Sidria-2 Collaborative Group . Wheeze and asthma in children: associations with body mass index, sports, television viewing, and diet. Epidemiology. 2008;19(5):747–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guler N, Kirerleri E, Ones U, Tamay Z, Salmayenli N, Darendeliler F. Leptin: does it have any role in childhood asthma? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(2):254–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mai XM, Böttcher MF, Leijon I. Leptin and asthma in overweight children at 12 years of age. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2004;15(6):523–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Shawwa BA, Al-Huniti NH, DeMattia L, Gershan W. Asthma and insulin resistance in morbidly obese children and adolescents. J Asthma. 2007;44(6):469–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cottrell L, Neal WA, Ice C, Perez MK, Piedimonte G. Metabolic abnormalities in children with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(4):441–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Shawwa B, Al-Huniti N, Titus G, Abu-Hasan M. Hypercholesterolemia is a potential risk factor for asthma. J Asthma. 2006;43(3):231–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Del-Rio-Navarro BE, Castro-Rodriguez JA, Garibay Nieto N, et al. Higher metabolic syndrome in obese asthmatic compared to obese nonasthmatic adolescent males. J Asthma. 2010;47(5):501–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee JM, Okumura MJ, Davis MM, Herman WH, Gurney JG. Prevalence and determinants of insulin resistance among U.S. adolescents: a population-based study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(11):2427–2432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Korsten-Reck U, Kromeyer-Hauschild K, Korsten K, Baumstark MW, Dickhuth HH, Berg A. Frequency of secondary dyslipidemia in obese children. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4(5):1089–1094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Musaad SM, Patterson T, Ericksen M, et al. Comparison of anthropometric measures of obesity in childhood allergic asthma: central obesity is most relevant. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(6):1321–7.e12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen YC, Tu YK, Huang KC, Chen PC, Chu DC, Lee YL. Pathway from central obesity to childhood asthma. Physical fitness and sedentary time are leading factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(10):1194–1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vangeepuram N, Teitelbaum SL, Galvez MP, Brenner B, Doucette J, Wolff MS. Measures of obesity associated with asthma diagnosis in ethnic minority children. J Obes. 2011;2011:517417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papoutsakis C, Chondronikola M, Antonogeorgos G, et al. Associations between central obesity and asthma in children and adolescents: a case-control study. J Asthma. 2015;52(2):128–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vo P, Makker K, Matta-Arroyo E, Hall CB, Arens R, Rastogi D. The association of overweight and obesity with spirometric values in minority children referred for asthma evaluation. J Asthma. 2013;50(1):56–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rastogi D, Canfield SM, Andrade A, et al. Obesity-associated asthma in children: a distinct entity. Chest. 2012;141(4):895–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rastogi D, Bhalani K, Hall CB, Isasi CR. Association of pulmonary function with adiposity and metabolic abnormalities in urban minority adolescents. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(5):744–752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davidson WJ, Mackenzie-Rife KA, Witmans MB, et al. Obesity negatively impacts lung function in children and adolescents. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014;49(10):1003–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li AM, Chan D, Wong E, Yin J, Nelson EA, Fok TF. The effects of obesity on pulmonary function. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88(4):361–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gibson N, Johnston K, Bear N, Stick S, Logie K, Hall GL. Expiratory flow limitation and breathing strategies in overweight adolescents during submaximal exercise. Int J Obes. 2014;38(1):22–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salome CM, King GG, Berend N. Physiology of obesity and effects on lung function. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2010;108(1):206–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tantisira KG, Litonjua AA, Weiss ST, Fuhlbrigge AL; Childhood Asthma Management Program Research Group . Association of body mass with pulmonary function in the Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP). Thorax. 2003;58(12):1036–1041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chu YT, Chen WY, Wang TN, Tseng HI, Wu JR, Ko YC. Extreme BMI predicts higher asthma prevalence and is associated with lung function impairment in school-aged children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009;44(5):472–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spathopoulos D, Paraskakis E, Trypsianis G, et al. The effect of obesity on pulmonary lung function of school aged children in Greece. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009;44(3):273–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pérez-Padilla R, Rojas R, Torres V, Borja-Aburto V, Olaiz G, Grp EW; The Empece Working Group . Obesity among children residing in Mexico City and its impact on lung function: a comparison with Mexican-Americans. Arch Med Res. 2006;37(1):165–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Y, Rennie D, Cormier Y, Dosman JA. Waist circumference associated with pulmonary function in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009;44(3):216–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Consilvio NP, Di Pillo S, Verini M, et al. The reciprocal influences of asthma and obesity on lung function testing, AHR, and airway inflammation in prepubertal children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2010;45(11):1103–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sidoroff V, Hyvärinen M, Piippo-Savolainen E, Korppi M. Lung function and overweight in school aged children after early childhood wheezing. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2011;46(5):435–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang F, del-Río-Navarro BE, Alcántara ST, et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, fibrinogen, and lung function in adolescents with asthma and obesity. Endocr Res. 2012;37(3):135–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jensen ME, Gibson PG, Collins CE, Wood LG. Airway and systemic inflammation in obese children with asthma. Eur Respir J. 2013;42(4):1012–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jensen ME, Gibson PG, Collins CE, Hilton JM, Wood LG. Diet-induced weight loss in obese children with asthma: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Exp Allergy. 2013;43(7):775–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sánchez Jiménez J, Herrero Espinet FJ, Mengibar Garrido JM, et al. Asthma and insulin resistance in obese children and adolescents. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2014;25(7):699–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang R, Custovic A, Simpson A, Belgrave DC, Lowe LA, Murray CS. Differing associations of BMI and body fat with asthma and lung function in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014;49(11):1049–1057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mancini MC. Metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents—criteria for diagnosis. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2009;1(1):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Messiah SE, Arheart KL, Lipshultz SE, Miller TL. Ethnic group differences in waist circumference percentiles among U.S. children and adolescents: estimates from the 1999–2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2011;9(4):297–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang SL, Shiao G, Chou P. Association between body mass index and allergy in teenage girls in Taiwan. Clin Exp Allergy. 1999;29(3):323–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schachter LM, Peat JK, Salome CM. Asthma and atopy in overweight children. Thorax. 2003;58(12):1031–1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Leeuwen JC, Hoogstrate M, Duiverman EJ, Thio BJ. Effects of dietary induced weight loss on exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in overweight and obese children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014;49(12):1155–1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Luna-Pech JA, Torres-Mendoza BM, Luna-Pech JA, Garcia-Cobas CY, Navarrete-Navarro S, Elizalde-Lozano AM. Normocaloric diet improves asthma-related quality of life in obese pubertal adolescents. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2014;163(4):252–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Khan UI, Rieder J, Cohen HW, Coupey SM, Wildman RP. Effect of modest changes in BMI on cardiovascular disease risk markers in severely obese, minority adolescents. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2010;4(3):e163–e246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee SC, Yang YH, Chuang SY, Liu SC, Yang HC, Pan WH. Risk of asthma associated with energy-dense but nutrient-poor dietary pattern in Taiwanese children. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2012;21(1):73–81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang SL, Pan WH. Dietary fats and asthma in teenagers: analyses of the first Nutrition and Health Survey in Taiwan (NAHSIT). Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31(12):1875–1880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Garcia-Marcos L, Canflanca IM, Garrido JB, et al. Relationship of asthma and rhinoconjunctivitis with obesity, exercise and Mediterranean diet in Spanish schoolchildren. Thorax. 2007;62(6):503–508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.de Batlle J, Garcia-Aymerich J, Barraza-Villarreal A, Antó JM, Romieu I. Mediterranean diet is associated with reduced asthma and rhinitis in Mexican children. Allergy. 2008;63(10):1310–1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nurmatov U, Devereux G, Sheikh A. Nutrients and foods for the primary prevention of asthma and allergy: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(3):724–33.e1, 30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Garcia-Marcos L, Castro-Rodriguez JA, Weinmayr G, Panagiotakos DB, Priftis KN, Nagel G. Influence of Mediterranean diet on asthma in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2013;24(4):330–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dandona P, Ghanim H, Chaudhuri A, Dhindsa S, Kim SS. Macronutrient intake induces oxidative and inflammatory stress: potential relevance to atherosclerosis and insulin resistance. Exp Mol Med. 2010;42(4):245–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aljada A, Mohanty P, Ghanim H, et al. Increase in intranuclear nuclear factor kappaB and decrease in inhibitor kappaB in mononuclear cells after a mixed meal: evidence for a proinflammatory effect. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(4):682–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Black PN, Sharpe S. Dietary fat and asthma: is there a connection? Eur Respir J. 1997;10(1):6–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wendell SG, Baffi C, Holguin F. Fatty acids, inflammation, and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(5):1255–1264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Horrobin DF. Low prevalences of coronary heart disease (CHD), psoriasis, asthma and rheumatoid arthritis in Eskimos: are they caused by high dietary intake of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), a genetic variation of essential fatty acid (EFA) metabolism or a combination of both? Med Hypotheses. 1987;22(4):421–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Glowacka E, Jedynak-Wasowicz U, Sanak M, Lis G. Exhaled eicosanoid profiles in children with atopic asthma and healthy controls. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2013;48(4):324–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lang JE, Mougey EB, Allayee H, et al. ; Nemours Network for Asthma Research . Nutrigenetic response to omega-3 fatty acids in obese asthmatics (NOOA): rationale and methods. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;34(2):326–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arora P, Kumar V, Batra S. Vitamin A status in children with asthma. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;13(3):223–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mizuno Y, Furusho T, Yoshida A, Nakamura H, Matsuura T, Eto Y. Serum vitamin A concentrations in asthmatic children in Japan. Pediatr Int. 2006;48(3):261–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nakamura K, Wada K, Sahashi Y, et al. Associations of intake of antioxidant vitamins and fatty acids with asthma in pre-school children. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(11):2040–2045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brehm JM, Celedón JC, Soto-Quiros ME, et al. Serum vitamin D levels and markers of severity of childhood asthma in Costa Rica. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(9):765–771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Somashekar AR, Prithvi AB, Gowda MN. Vitamin D levels in children with bronchial asthma. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(10):PC04–PC07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yao TC, Tu YL, Chang SW, et al. ; Prediction of Allergies in Taiwanese Children (PATCH) Study Group . Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in relation to lung function and exhaled nitric oxide in children. J Pediatr. 2014;165(6):1098–1103.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mann EH, Chambers ES, Pfeffer PE, Hawrylowicz CM. Immunoregulatory mechanisms of vitamin D relevant to respiratory health and asthma. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1317:57–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ooi JH, Li Y, Rogers CJ, Cantorna MT. Vitamin D regulates the gut microbiome and protects mice from dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis. J Nutr. 2013;143(10):1679–1686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Verhulst SL, Vael C, Beunckens C, Nelen V, Goossens H, Desager K. A longitudinal analysis on the association between antibiotic use, intestinal microflora, and wheezing during the first year of life. J Asthma. 2008;45(9):828–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cho SH, Stanciu LA, Holgate ST, Johnston SL. Increased interleukin-4, interleukin-5, and interferon-γ in airway CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in atopic asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(3):224–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Litonjua AA, Gold DR Asthma and obesity: common early-life influences in the inception of disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;121(5):1075–1084; quiz 1085–1076 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 82.Jones LR, Steer CD, Rogers IS, Emmett PM. Influences on child fruit and vegetable intake: sociodemographic, parental and child factors in a longitudinal cohort study. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(7):1122–1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Carper JL, Orlet Fisher J, Birch LL. Young girls’ emerging dietary restraint and disinhibition are related to parental control in child feeding. Appetite. 2000;35(2):121–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Santiago-Torres M, Adams AK, Carrel AL, LaRowe TL, Schoeller DA. Home food availability, parental dietary intake, and familial eating habits influence the diet quality of urban Hispanic children. Child Obes. 2014;10(5):408–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Arredondo EM, Elder JP, Ayala GX, Campbell N, Baquero B, Duerksen S. Is parenting style related to children’s healthy eating and physical activity in Latino families? Health Educ Res. 2006;21(6):862–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brogan K, Idalski Carcone A, Jen KL, Ellis D, Marshall S, Naar-King S. Factors associated with weight resilience in obesogenic environments in female African-American adolescents. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):718–724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Scott HA, Gibson PG, Garg ML, et al. Dietary restriction and exercise improve airway inflammation and clinical outcomes in overweight and obese asthma: a randomized trial. Clin Exp Allergy. 2013;43(1):36–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cox R, Skouteris H, Rutherford L, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Dell’Aquila D, Hardy LL. Television viewing, television content, food intake, physical activity and body mass index: a cross-sectional study of preschool children aged 2–6 years. Health Promot J Austr. 2012;23(1):58–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ghavamzadeh S, Khalkhali HR, Alizadeh M. TV viewing, independent of physical activity and obesogenic foods, increases overweight and obesity in adolescents. J Health Popul Nutr. 2013;31(3):334–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sherriff A, Maitra A, Ness AR, et al. Association of duration of television viewing in early childhood with the subsequent development of asthma. Thorax. 2009;64(4):321–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rasmussen F, Lambrechtsen J, Siersted HC, Hansen HS, Hansen NC. Low physical fitness in childhood is associated with the development of asthma in young adulthood: the Odense schoolchild study. Eur Respir J. 2000;16(5):866–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vlaski E, Stavric K, Seckova L, Kimovska M, Isjanovska R. Influence of physical activity and television-watching time on asthma and allergic rhinitis among young adolescents: preventive or aggravating? Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2008;36(5):247–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rastogi D, Khan UI, Isasi CR, Coupey SM. Associations of obesity and asthma with functional exercise capacity in urban minority adolescents. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2012;47(11):1061–1069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.O’Rourke RW, White AE, Metcalf MD, et al. Hypoxia-induced inflammatory cytokine secretion in human adipose tissue stromovascular cells. Diabetologia. 2011;54(6):1480–1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ferrante AW, Jr. The immune cells in adipose tissue. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15(suppl 3):34–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Luczyński W, Wawrusiewicz-Kurylonek N, Iłendo E, et al. Generation of functional T-regulatory cells in children with metabolic syndrome. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 2012;60(6):487–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Manigrasso MR, Ferroni P, Santilli F, et al. Association between circulating adiponectin and interleukin-10 levels in android obesity: effects of weight loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(10):5876–5879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Catli G, Anik A, Abaci A, Kume T, Bober E. Low omentin-1 levels are related with clinical and metabolic parameters in obese children. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2013;121(10):595–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hong EG, Ko HJ, Cho YR, et al. Interleukin-10 prevents diet-induced insulin resistance by attenuating macrophage and cytokine response in skeletal muscle. Diabetes. 2009;58(11):2525–2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yuksel H, Sogut A, Yilmaz O, Onur E, Dinc G. Role of adipokines and hormones of obesity in childhood asthma. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2012;4(2):98–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nagel G, Koenig W, Rapp K, Wabitsch M, Zoellner I, Weiland SK. Associations of adipokines with asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in German schoolchildren. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2009;20(1):81–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Youssef DM, Elbehidy RM, Shokry DM, Elbehidy EM. The influence of leptin on Th1/Th2 balance in obese children with asthma. J Bras Pneumol. 2013;39(5):562–568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rastogi D, Fraser S, Oh J, et al. Inflammation, metabolic dysregulation, and pulmonary function among obese urban adolescents with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(2):149–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Baek HS, Kim YD, Shin JH, Kim JH, Oh JW, Lee HB. Serum leptin and adiponectin levels correlate with exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in children with asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011;107(1):14–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dixon AE, Johnson SE, Griffes LV, et al. Relationship of adipokines with immune response and lung function in obese asthmatic and non-asthmatic women. J Asthma. 2011;48(8):811–817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Visness CM, London SJ, Daniels JL, et al. Association of childhood obesity with atopic and nonatopic asthma: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2006. J Asthma. 2010;47(7):822–829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Visness CM, London SJ, Daniels JL, et al. Association of obesity with IgE levels and allergy symptoms in children and adolescents: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2006. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(5):1163–1169, 1169.e1–1169.e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Han Y-Y, Forno E, Celedón JC. Adiposity, fractional exhaled nitric oxide, and asthma in U.S. children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(1):32–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Santamaria F, Montella S, De Stefano S, et al. Asthma, atopy, and airway inflammation in obese children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(4):965–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Erkoçoğlu M, Kaya A, Ozcan C, et al. The effect of obesity on the level of fractional exhaled nitric oxide in children with asthma. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2013;162(2):156–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Leung TF, Li CY, Lam CWK, et al. The relation between obesity and asthmatic airway inflammation. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2004;15(4):344–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Huang F, del-Río-Navarro BE, Monge JJ, et al. Endothelial activation and systemic inflammation in obese asthmatic children. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2008;29(5):453–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Michelson PH, Williams LW, Benjamin DK, Barnato AE. Obesity, inflammation, and asthma severity in childhood: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001-2004. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;103(5):381–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Khan UI, Rastogi D, Isasi CR, Coupey SM. Independent and synergistic associations of asthma and obesity with systemic inflammation in adolescents. J Asthma. 2012;49(10):1044–1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sah PK, Gerald Teague W, Demuth KA, Whitlock DR, Brown SD, Fitzpatrick AM. Poor asthma control in obese children may be overestimated because of enhanced perception of dyspnea. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1(1):39–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Peters MC, Fahy JV. Type 2 immune responses in obese individuals with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(6):633–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Moore WC, Hastie AT, Li X, et al. ; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Severe Asthma Research Program . Sputum neutrophil counts are associated with more severe asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(6):1557–63.e5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Periyalil HA, Gibson PG, Wood LG. Immunometabolism in obese asthmatics: are we there yet? Nutrients. 2013;5(9):3506–3530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sutherland ER, Goleva E, Strand M, Beuther DA, Leung DY. Body mass and glucocorticoid response in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(7):682–687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Price D, Musgrave SD, Shepstone L, et al. Leukotriene antagonists as first-line or add-on asthma-controller therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(18):1695–1707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Berry MA, Hargadon B, Shelley M, et al. Evidence of a role of tumor necrosis factor alpha in refractory asthma. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(7):697–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Levy-Marchal C, Arslanian S, Cutfield W, et al. ; ESPE-LWPES-ISPAD-APPES-APEG-SLEP-JSPE; Insulin Resistance in Children Consensus Conference Group . Insulin resistance in children: consensus, perspective, and future directions. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(12):5189–5198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Goran MI, Ball GD, Cruz ML. Obesity and risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease in children and adolescents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(4):1417–1427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Arshi M, Cardinal J, Hill RJ, Davies PSW, Wainwright C. Asthma and insulin resistance in children. Respirology. 2010;15(5):779–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Chen YC, Tung KY, Tsai CH, et al. Lipid profiles in children with and without asthma: interaction of asthma and obesity on hyperlipidemia. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2013;7(1):20–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hyun E, Ramachandran R, Hollenberg MD, Vergnolle N. Mechanisms behind the anti-inflammatory actions of insulin. Crit Rev Immunol. 2011;31(4):307–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Liu ML, Dong HY, Zhang B, et al. Insulin reduces LPS-induced lethality and lung injury in rats. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2012;25(6):472–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lumeng CN, Saltiel AR. Inflammatory links between obesity and metabolic disease. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(6):2111–2117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Dekkers BG, Schaafsma D, Tran T, Zaagsma J, Meurs H. Insulin-induced laminin expression promotes a hypercontractile airway smooth muscle phenotype. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41(4):494–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Noveral JP, Bhala A, Hintz RL, Grunstein MM, Cohen P. Insulin-like growth factor axis in airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1994;267(6 pt 1):L761–L765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Nie Z, Jacoby DB, Fryer AD. Hyperinsulinemia potentiates airway responsiveness to parasympathetic nerve stimulation in obese rats. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2014;51(2):251–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Bossé Y. Endocrine regulation of airway contractility is overlooked. J Endocrinol. 2014;222(2):R61–R73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Fenger RV, Gonzalez-Quintela A, Linneberg A, et al. The relationship of serum triglycerides, serum HDL, and obesity to the risk of wheezing in 85,555 adults. Respir Med. 2013;107(6):816–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Lumia M, Luukkainen P, Tapanainen H, et al. Dietary fatty acid composition during pregnancy and the risk of asthma in the offspring. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011;22(8):827–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Wood LG, Garg ML, Gibson PG. A high-fat challenge increases airway inflammation and impairs bronchodilator recovery in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(5):1133–1140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Rosenkranz SK, Townsend DK, Steffens SE, Harms CA. Effects of a high-fat meal on pulmonary function in healthy subjects. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;109(3):499–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.von Mutius E. Gene-environment interactions in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(1):3–11, quiz 12–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Szarc vel Szic K, Ndlovu MN, Haegeman G, Vanden Berghe W. Nature or nurture: let food be your epigenetic medicine in chronic inflammatory disorders. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80(12):1816–1832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Almén MS, Jacobsson JA, Moschonis G, et al. Genome wide analysis reveals association of a FTO gene variant with epigenetic changes. Genomics. 2012;99(3):132–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Martínez JA, Cordero P, Campión J, Milagro FI. Interplay of early-life nutritional programming on obesity, inflammation and epigenetic outcomes. Proc Nutr Soc. 2012;71(2):276–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Stefanowicz D, Hackett TL, Garmaroudi FS, et al. DNA methylation profiles of airway epithelial cells and PBMCs from healthy, atopic and asthmatic children. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Kim YJ, Park SW, Kim TH, et al. Genome-wide methylation profiling of the bronchial mucosa of asthmatics: relationship to atopy. BMC Med Genet. 2013;14(39):39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Kwon NH, Kim JS, Lee JY, Oh MJ, Choi DC. DNA methylation and the expression of IL-4 and IFN-gamma promoter genes in patients with bronchial asthma. J Clin Immunol. 2008;28(2):139–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Rastogi D, Suzuki M, Greally JM. Differential epigenome-wide DNA methylation patterns in childhood obesity-associated asthma. Sci Rep. 2013;3(2164):2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.MacIver NJ, Michalek RD, Rathmell JC. Metabolic regulation of T lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:259–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Melén E, Himes BE, Brehm JM, et al. Analyses of shared genetic factors between asthma and obesity in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(3):631–7.e1, 8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.González JR, Cáceres A, Esko T, et al. A common 16p11.2 inversion underlies the joint susceptibility to asthma and obesity. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94(3):361–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Oguri K, Tachi T, Matsuoka T. Visceral fat accumulation and metabolic syndrome in children: the impact of Trp64Arg polymorphism of the beta3-adrenergic receptor gene. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102(6):613–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Silverman EK, Kwiatkowski DJ, Sylvia JS, et al. Family-based association analysis of beta2-adrenergic receptor polymorphisms in the childhood asthma management program. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112(5):870–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Aoki T, Hirota T, Tamari M, et al. An association between asthma and TNF-308G/A polymorphism: meta-analysis. J Hum Genet. 2006;51(8):677–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Sookoian SC, González C, Pirola CJ. Meta-analysis on the G-308A tumor necrosis factor alpha gene variant and phenotypes associated with the metabolic syndrome. Obes Res. 2005;13(12):2122–2131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Hamid YH, Urhammer SA, Glümer C, et al. The common T60N polymorphism of the lymphotoxin-alpha gene is associated with type 2 diabetes and other phenotypes of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetologia. 2005;48(3):445–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Wang TN, Chen WY, Wang TH, Chen CJ, Huang LY, Ko YC. Gene-gene synergistic effect on atopic asthma: tumour necrosis factor-alpha-308 and lymphotoxin-alpha-NcoI in Taiwan’s children. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34(2):184–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents. Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents: summary report. Pediatrics 2011; 128(suppl 5):S213–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]