Abstract

Genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators are outstanding tools for the assessment of intracellular/organelle Ca2+ dynamics. Basically, most indicators contain the Ca2+-binding site of a (mutated) cytosolic protein that interacts with its natural (mutated) interaction partner upon binding of Ca2+. Consequently, a change in the structure of the sensor occurs that, in turn, alters the fluorescent properties of the sensor. Herein, we present a new type of genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator for the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (apoK1-er (W. F. Graier, K. Osibow, R. Malli, and G. M. Kostner, patent application number 05450006.1 at the European patent office)) that is based on a single kringle domain from apolipoprotein(a), which is flanked by yellow and cyan fluorescent protein at the 3′- and 5′-ends, respectively. Notably, apoK1-er does not interact with Ca2+ itself but serves as a substrate for calreticulin, the main constitutive Ca2+-binding protein in the ER. ApoK1-er assembles with calreticulin and the protein disulfide isomerase ERp57 and undergoes a conformational shift in a Ca2+-dependent manner that allows fluorescence resonance energy transfer between the two fluorophores. This construct primarily offers three major advantages compared with the already existing probes: (i) it resolves perfectly the physiological range of the free Ca2+ concentration in the ER, (ii) expression of apoK1-er does not affect the Ca2+ buffering capacity of the ER, and (iii) apoK1-er is not inactivated by binding of constitutive interaction partners that prevent Ca2+-dependent conformational changes. These unique characteristics of apoK1-er make this sensor particularly attractive for studies on ER Ca2+ signaling and dynamics in which alteration of Ca2+ fluctuations by expression of any additional Ca2+ buffer essentially has to be avoided.

The ER3 represents the main Ca2+ store in most mammalian cells and is crucially involved in cellular Ca2+ signaling. In particular, by its ability to release Ca2+ through receptor channels, such as inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors or ryanodine receptors, as well as by its large Ca2+ sequestration capacity, the ER is crucial for cellular Ca2+ homeostasis. However, the ER not only considerably contributes to cytosolic Ca2+ signaling, but ER Ca2+ release is also important for mitochondrial Ca2+ signaling (1) and activation of Ca2+-activated plasma membrane ion channels (2, 3). Moreover, the free ER Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]ER) is a key regulator for the activity of ER resident enzymes that are involved in fundamental processes, such as protein folding or lipid biosynthesis (4).

In view of such pivotal role of the ER Ca2+ homeostasis for cell function, reliable measurements of intraluminal Ca2+ dynamics are important for our understanding of Ca2+-dependent signaling. Initially, synthetic fluorescent chelators with low Ca2+-affinity (e.g. Mag-fura-2) have been established, which are loaded into the ER under certain conditions thus being suitable for intraluminal Ca2+ measurements in the ER (5). Nevertheless, the targeting of these dyes is not specific, and the large proportion of fluorescence that accumulates in the cytosol influences measurements of [Ca2+]ER. The introduction of the genetically encoded bioluminescent protein aequorin allowed specific targeting to the ER and excellent measurements of ER Ca2+ concentration (6). However, aequorin requires the incorporation of coelenterazine and is irreversibly consumed by Ca2+ and, thus, long term measurements in the ER are difficult. Moreover, because of its limited light emission, this sensor is hardly suitable for image analysis, an emerging necessity for studies focused on subcellular Ca2+ homeostasis or intraorganelle Ca2+ cross-talk.

In an additional approach, intramolecular fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between two GFP mutants that were initially bridged by the calmodulin-binding domain from smooth muscle light chain kinase (M13), which undergoes structural changes upon binding of constitutive Ca2+/calmodulin, was utilized (7, 8). This concept was further improved by the additional insertion of calmodulin between the two GFP mutants (9, 10) and the design of circularly permutated GFP Ca2+ sensors (e.g. pericam, 11). However, the latter could not be successfully targeted into the ER so far. In a similar approach, fragments of the chicken skeletal muscle or human cardiac muscle troponin C were inserted between two fluorophores (12). These so-called S- and C-troponeon monitor Ca2+ independently of M13 and calmodulin.

Despite the diverse concepts of these fluorescent Ca2+ sensors, in all types the binding of Ca2+ to specific Ca2+-binding domains subsequently alters the fluorescent properties of the protein. The latter sensors most frequently use calmodulin or troponin C as binding sites. Because these proteins are naturally found predominantly in the cytosol, their affinity for Ca2+ is suitable to monitor Ca2+ in compartments with similar Ca2+ concentration dynamics than its natural environment (e.g. cytosol, mitochondria). Particularly for the ER, where the free Ca2+ concentration exceeds that in the cytosol by more than 3 orders of magnitude, the Ca2+-bindings site of the sensor needed to be redesigned to adapt its Ca2+ sensitivity to this high Ca2+ environment (for review see Ref. 13). Recently, a new sensor was introduced (i.e. D1ER) in which not only calmodulin but also M13 was mutated, and, thus, interference with constitutive calmodulin is strongly diminished (14).

However, despite these significant improvements, all sensors may affect the free Ca2+ concentration of the compartment/organelle as they conceptually act as Ca2+ chelators. Notably, an elevation of intraluminal Ca2+ binding capacity in the ER by overexpression of calreticulin has been found to modulate Ca2+ uptake and release in the ER and mitochondria as well as to reduce store-operated Ca2+ entry in HEK 293 cells (15).

Accordingly, we have designed a genetically encoded FRET sensor that combines the advantages of the existing tools and offers excellent targeting into the ER and a Ca2+ sensitivity that is suitable for Ca2+ measurements in the ER environment but does not contain a Ca2+ binding domain, which may affect cellular/subcellular/interorganelle Ca2+ signaling.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Cell culture media and substitutes, pBudCE4.1, primers, and DNA standards were from Invitrogen. pcDNA3 was from Clontech. Fetal calf serum was from PAA (Linz, Austria), and cell culture plasticware was purchased from Bertoni (Vienna, Austria). TransFast™, restriction enzymes, and T4 ligase were obtained from Promega. 2,5-Di-(tert-butyl)-1,4-hydroquinone (BHQ), dl-buthionine-[SR] sulfoximine (BSO), digitonin, histamine, MES, nigericin, monensin, and ionomycin were from Sigma-Aldrich. Hot Fire DNA Polymerase I was from Solis BioDyne (Tartu, Estonia). Antibodies and luminol reagent were obtained from Santa Cruz (Szabo Scandic, Vienna Austria). X-ray films were from Siemens (Graz, Austria). Nitrocellulose, protein standards, dNTPs, and all other chemicals were purchased from Roth (Lactan, Graz, Austria).

Cell Culture and Transfection

EA.hy 926 cells at passage ≥40 were grown on glass coverslips to ~80% confluency and transiently transfected with 2 µg of plasmid 2 days prior to experiments using TransFast™. To yield stable expression, HEK 293 cells transfected with 5 µg of DNA per 6-cm dish were propagated in medium containing 100 µg/ml G418, and fluorescent colonies were consequently subcloned.

DNA Cloning

One and two kringles of apo(a) were amplified by PCR, thereby introducing SphI and SacI restriction sites at their 5′- and 3′-ends, respectively. YC4er and YC2.1 (10) were transferred into pUC19 (New England Biolabs, Frankfurt, Germany) as full-length HindIII/EcoRI fragments, and the calmodulin-M13 regions were exchanged for the restricted PCR products. The resultant constructs, termed apoK1/2-cyto/er, were confirmed by automated sequencing. The same PCR-based strategy was used to generate apoK12-er, containing 12 kringles of apo(a). To create ER-targeted sensors devoid of all 6 cysteines or both putative N-glycosylation sites, respectively, site-directed mutagenesis with primers bearing the intended mutations was performed. By use of internal restriction sites as indicated in Fig. 1c, apoK1-er was substituted sequentially for the respective mutated fragments. To allow introduction of the constructs via NotI/EcoRI into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3, an additional NotI site was introduced between HindIII and EcoRI, and all following restriction sites were removed by blunt end ligation. For double transfection apoK1-er and mt-DsRed were inserted into the two multiple cloning sites of the transfection vector pBudCE4.1.

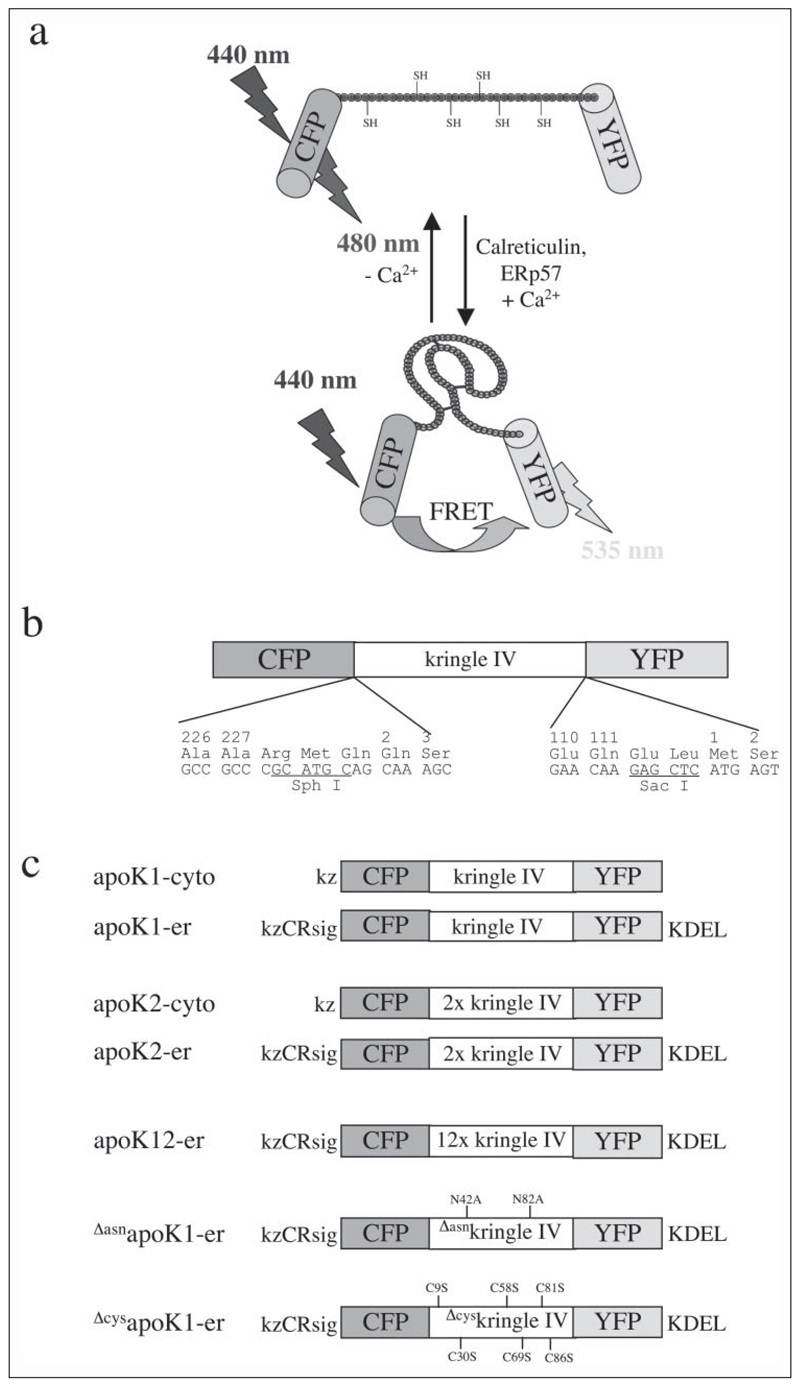

FIGURE 1. Schematic structure of apoK sensors.

a, proposed model of the Ca2+-dependent conformational shift from the linear extended to the compact structure of the type IV kringle of apo(a) within apoK1 thereby facilitating FRET to occur by reducing the distance between the donor (CFP) and acceptor (YFP) fluorophores. b, domain structure of apoK1 indicating the boundaries and utilized restriction sites between CFP, kringle IV of apo(a), and YFP. c, design of apoK sensors and control constructs for expression and imaging in mammalian cells. Positions of the mutated amino acids are numbered according to the mature apo(a) without signal sequence. CRsig, ER signal sequence of calreticulin (MLLSVPLLLGLLGLAAAD); KDEL, ER retention signal; kz, Kozak sequence for optimal translation in mammalian cells. The significant mutations in the fluorescent proteins are: CFP, F46L/S65T/Y66W/N146I/M153T/V163A/N212K and YFP, S65G/S72A/T203Y.

Immunohistochemistry

Following fixation by 4.5% paraformaldehyde, EA.hy 926 cells grown on glass coverslips were permeabilized by 0.6% Triton X-100 and incubated with specific antibodies against calreticulin, calnexin, or ERp57. A Cy3-labeled secondary antibody (Clontech) was used for visualization.

Confocal Microscopy

Image acquisition was performed on an array confocal laser scanning microscope (VoxCell Scan, Visitech) consisting of a Zeiss Axiovert 200 m (Vienna, Austria) and a QLC laser confocal scanning module (VisiTech, Visitron Systems, Puchheim, Germany) controlled by Metamorph 5.0 (Universal Imaging, Visitron Systems) as described previously (16, 17).

FRET Measurement

Experiments were performed on a Nikon inverted microscope (Eclipse 300TE; Nikon, Optoteam, Vienna Austria) equipped with a CFI Plan Fluor 40× oil immersion objective, an epifluorescence system (Opti Quip, Highland Mills, NY), computer controlled z-stage and filter wheel (Ludl Electronic Products, Haw-thorne, NY), and a liquid-cooled CCD-camera (Quantix KAF 1400G2, Roper Scientific, Acton, MA) and controlled by Metafluor 4.0 (Visitron Systems). As described previously (3, 16), FRET-based sensors were excited at 440 nm (440AF21; Omega Optical, Brattleboro, VT), and emission was monitored at 480 and 535 nm using an optical beam splitter (Dual View Micro-Imager™; Optical Insights, Visitron Systems). Hepes-buffered solutions containing 145 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, and 10 mm Hepes acid (pH adjusted to 7.4) with 2 mm Ca2Cl or 1 mm EGTA were used.

pH and Ca2+ Titration

To characterize the pH sensitivity of the FRET-based ER Ca2+ sensors, a series of buffers with pHs ranging from 5 to 9 were prepared that contained 10 µm nigericin and 10 µm monensin and consisted of 140 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl, 0.5 mm CaCl2, and either 20 mm MES (for pH 5– 6.5), 20 mm HEPES (for pH 7–7.5) or 20 mm Tris-HCl (for pH 8 –9). For pH/Ca2+ titrations, cells were permeabilized with digitonin (10 µm) and ionomycin (1.5 µm) in the respective buffer. The free Ca2+ concentrations ranged from 10−6 to 10−1 m and were set according to the Buffercalc program (Stanford, CA).

Redox Sensitivity

Cells were depleted from GSH by preincubation in GSH-free medium containing 5 mm BSO for 12 h (18). Cells were permeabilized as described above, and the change in fluorescence upon the switch between 10−6 and 10−3 m free Ca2+ was recorded in the presence of GSH from 0 to 10 mm.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Lysates of HEK 293 cells stably expressing apoK1-er were incubated with specific antibodies against calreticulin, calnexin, or ERp57, respectively, and the immune complexes were precipitated with Protein G-Sepharose 4 Fast Flow (Immunoprecipitation Starter Pack, Amersham Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Proteins were separated on 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and detected by Western blot analysis using chemiluminescence according to standard protocols.

Statistics

Analysis of variance and Scheffe’s post hoc F test were used for evaluation of the statistical significance. p < 0.05 was determined to be significant.

RESULTS

To achieve a high resolution and dynamic readout of ER Ca2+ concentration, we took advantage of the structural shift from a linear extended to a compact kringle conformation during the maturation of apo(a) (19) and designed a fluorescent protein sensor for [Ca2+]ER. Consequently, a defined number of kringle IV sequences of apo(a) were flanked by the cDNA coding for the cyan (CFP) and yellow (YFP) variants of green fluorescent protein at the 5′- and 3′-ends, respectively (Fig.1, a and b). By assembly of a complex with the chaperone and protein disulfide isomerase (i.e. calreticulin/ERp57, calnexin/ERp57) (20)) the formation of the kringle(s) was assumed to occur. This structural shortening should result in FRET between the 5′-flanking donor (CFP) and the 3′-located acceptor (YFP) (Fig. 1a).

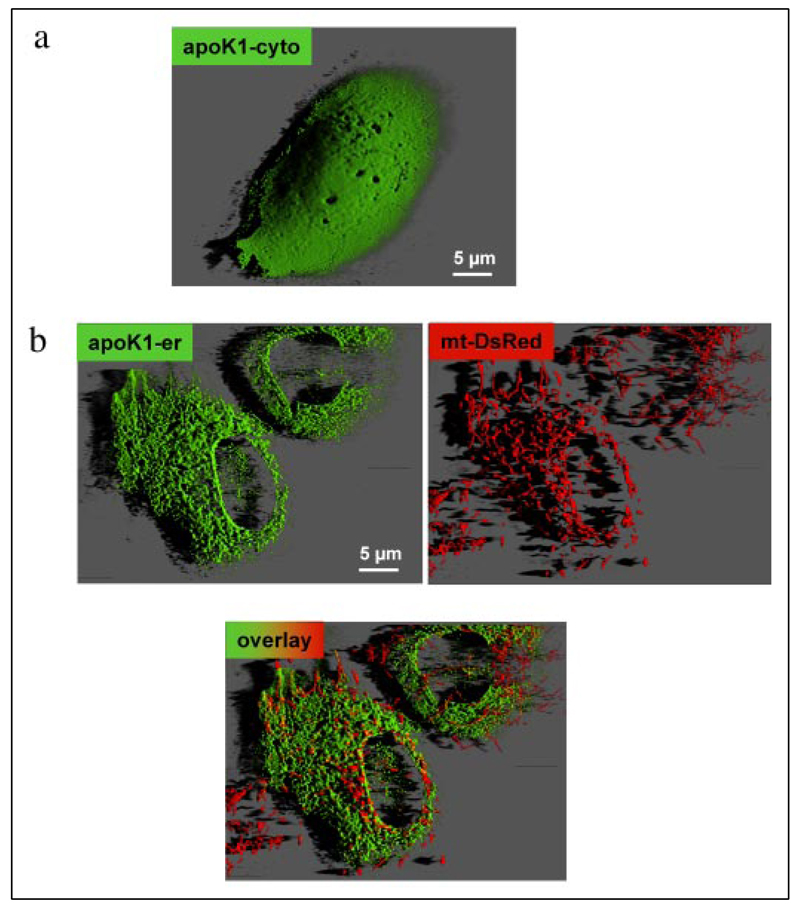

FRET efficiency decreases by the sixth order of magnitude of the distance between donor and acceptor fluorophores and depends on their relative orientation, which is unpredictable and therefore assumed to be constant (21). Thus, two constructs with either one (apoK1) or two (apoK2) kringle IV domain(s) between the two fluorophores were designed and tested for FRET efficiency upon protein folding (Fig. 1a). Upon overexpression in endothelial cells the respective proteins localized in the cytosol (Fig. 2a). Because targeting of the sensors into the lumen of the ER is prerequisite for the Ca2+-dependent maturation of kringle IV, the calreticulin signal sequence, and KDEL, which were successful for ER-targeting (10, 22), were introduced at the 5′- and 3′-ends of the constructs, respectively (Fig. 1c). As a consequence, successful targeting of the kringle IV containing sensors to the ER was achieved (Fig. 2b). The structural integrity of the ER, the mitochondrial organization, and the well established network of ER and mitochondria (Fig. 2b) were not affected by overexpression of apoK1-er. Immunohistochemistry revealed co-localization of apoK1-er with calreticulin, calnexin, and ERp57 (data not shown).

FIGURE 2. Intracellular distribution of the apoK1 constructs.

Endothelial cells were transiently transfected with either apoK1-cyto in pcDNA3 (a) or pBudCE4.1 encoding apoK1-er and mt-DsRed simultaneously (b). Distribution of the proteins was monitored at 488 nm excitation and 535 nm emission (apoK1-er) or 570 nm (mt-DsRed) on an array laser scanning microscope as described previously (16, 17, 31, 39). Out of focus fluorescence was removed using quick maximum likelihood deconvolution algorithm (Hygens Professional, SVI, Hilversum, The Netherlands), and three-dimensional reconstruction was performed with Imaris 4.0.3 (Bitplane, Zurich, Switzerland).

To investigate whether the appearance of FRET from the apoK sensors is based on successful protein processing and folding that achieves a structural protein shortening and, thus, facilitates energy transfer between the two narrow fluorophores, several apoK variants were designed and targeted into the ER lumen. First, the two glycosylation sites of apoK1-er at positions 42 and 82 of kringle IV were mutated by exchange of the constitutive L-asparagine to L-alanine (ΔasnapoK1-er; Fig. 1c). Such an approach has been used frequently to prevent protein glycosylation inside the ER, which is a prerequisite for further processing, and, thus, to preclude that the respective protein is subject for the protein folding machinery (23, 24). Second, the cysteines at position 9, 30, 58, 69, 81, and 86 of kringle IV were exchanged by site-directed mutagenesis to L-serine (ΔcysapoK1-er; Fig. 1c). Because binding of ERp57 to its substrate as well as the folding/shortening of the apo(a)/apoK sensors are thought to depend on the formation of disulfide bridges that built up the known kringle structure (Fig. 1a), such a construct may not be suitable for Ca2+-dependent folding at the calreticulin/ERp57 complex. Third, 12 copies of the kringle IV domain were cloned between CFP and YFP (apoK12-er, Fig. 1c) to enlarge the distance between the fluorescence donor and the putative energy acceptor and, thus, to prevent FRET from occurring even after the protein was folded properly. Notably, all constructs targeted nicely into the ER and did not exhibit any differences in intracellular localization compared with apoK1-er.

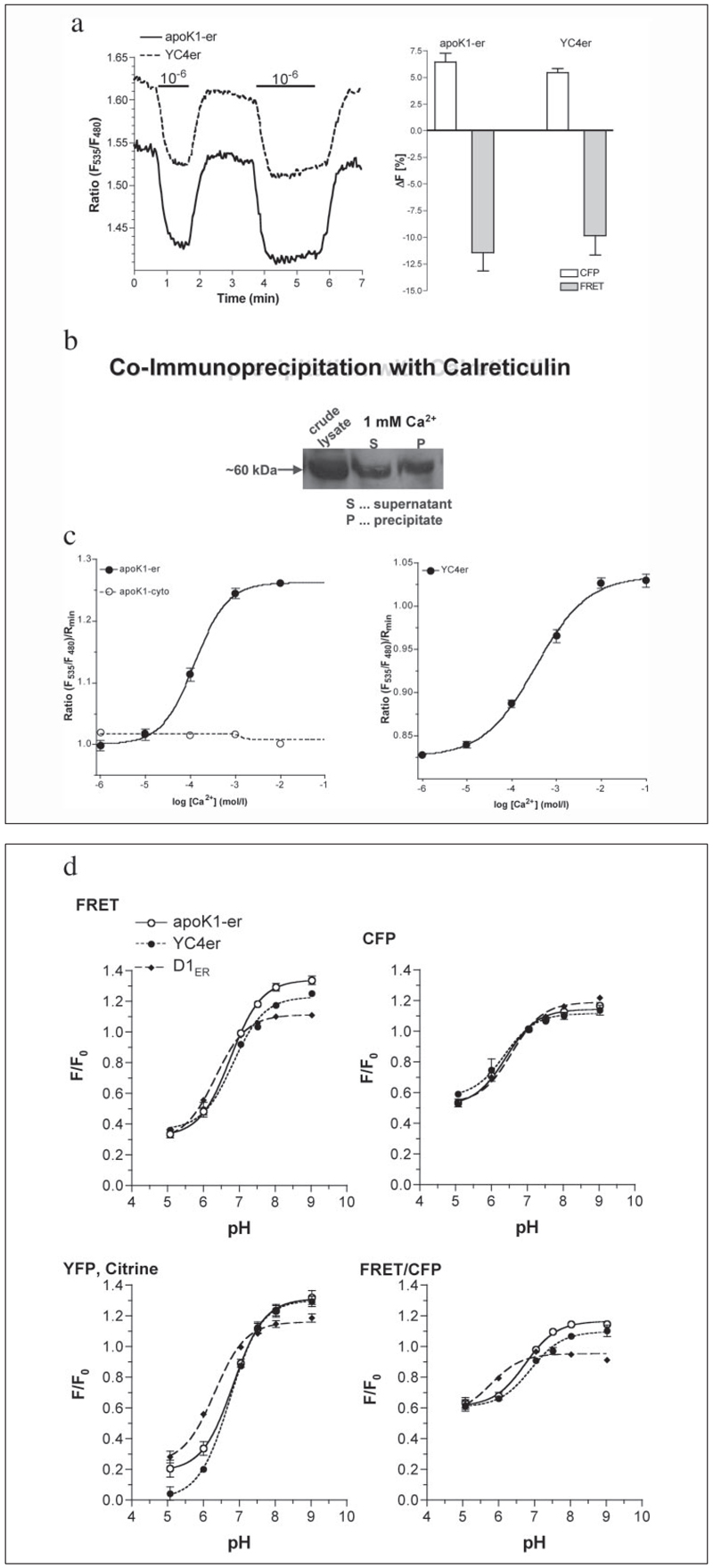

In HEK 293 cells that stably expressed apoK1, the sensor exhibited the expected spectrum representing the overlay of the two fluorescent proteins CFP and YFP (data not shown). In contrast to apoK1-cyto, the fluorescence profile of apoK1-er was similar to YC4er and changed upon chelating intraluminal Ca2+ indicating the loss of FRET by protein unfolding (Fig. 3a). ApoK1-er was isolated from stably expressing HEK 293 cells using an affinity column carrying an antibody against apo(a) as described previously (25). The isolated protein did not reveal any sensitivity to Ca2+ ions up to 2 mm free Ca2+ thus indicating that the designed protein per se does not sense Ca2+. In addition, no changes in the fluorescence properties of the isolated and reduced apoK1-er protein were found if the redox potential was alternated stepwise from 0.1 mm GSSG/0 mm GSH to 0.1 mm GSSG/10 mm GSH. Thus, at least in the physiological redox range of the ER (26), the fluorescence of the isolated apoK1-er protein was not sensitive to changes in redox state of its environment (data not shown). In line with our immunohistochemical data described above, apoK1-er protein was co-immunoprecipitated with calreticulin (Fig. 3b), calnexin, and ERp57 (data not shown), suggesting that inside the ER lumen this putative folding sensor is recognized by the prominent Ca2+-dependent chaperones and forms a complex with the respective disulfide isomerase.

FIGURE 3. Characterization of apoK1-er.

a, original tracings (left graph) and magnitude of changes in CFP fluorescence and FRET intensity in permeabilized transiently transfected endothelial cells (right graph; 100% are the values under Ca2+ saturation (i.e. 1 mm intraluminal free Ca2+); apoK1-er, n = 14; YC4er, n = 15) in response to the switch from 1 mm to 1 µm intraluminal free Ca2+ as the lines indicate. b, co-immunoprecipitation of apoK1-er with calreticulin. HEK 293 cells stably expressing apoK1-er were lysed and the sensor co-precipitated with polyclonal anti-calreticulin antibody immobilized to Protein G-Sepharose beads. c, in situ concentration response curves of apoK1-er (left, n = 14) and YC4er (right, n = 6) in permeabilized endothelial cells (1.5 µm ionomycin and 10 µm digitonin). d, comparison of the pH sensitivities of apoK1-er (n = 5), YC4er (n = 3– 4), and D1ER (n = 7). In the presence of 10 µm nigericin and 10 µm monensin (see “Experimental Procedures”) intraluminal pH was set to the levels indicated, and changes in FRET and the fluorescences of CFP, YFP/citrine as well as in the ratio FRET/CFP were obtained. F0 represents the initial value in each individual cell prior pH titration.

To verify whether the concept of apoK1-er allows measurement of the Ca2+ concentration in the ER lumen of a living cell, the appearance of FRET due to the shortened distance between the donor and acceptor proteins was monitored initially in situ by a conventional Ca2+ calibration assay. Endothelial cells were transiently transfected with either apoK1-er or apoK1-cyto. After 48 h, the cells were permeabilized and intraluminal Ca2+ concentration was stepwise elevated by addition of 1 µm to 10 mm free Ca2+ (calculated according Buffercalc for MacOS 7–9). In single permeabilized cells, apoK1-er was visualized at 440 nm excitation and 480 nm (donor fluorescence) and 535 nm (FRET) emission (Fig. 1a). Inside the ER lumen, apoK1-er folded in a Ca2+-dependent manner where the apparent KD was 124.2 (120.7–127.7) µm with a Hill coefficient of 1.148 –1.245 (Fig. 3c, left panel). In comparison, the frequently used ER Ca2+ sensor, YC4er was found to have a KD of 344.6 (325.4 –365.0) µm in the same protocol (Fig. 3c, right panel), which is similar to that published in HeLa cells (27).

Furthermore, the pH sensitivity of apoK1-er was compared with that of YC4er, which also contains CFP and YFP, and the improved ER Ca2+ probe D1ER, where YFP has been replaced by citrine (Fig. 3d). As expected the pH sensitivities of the sensors containing YFP were identical and more pronounced than the citrine-containing probe (Fig. 3d). Nevertheless, all probes allowed ER Ca2+ measurements in a pH range of at least 6.5– 8 (data not shown).

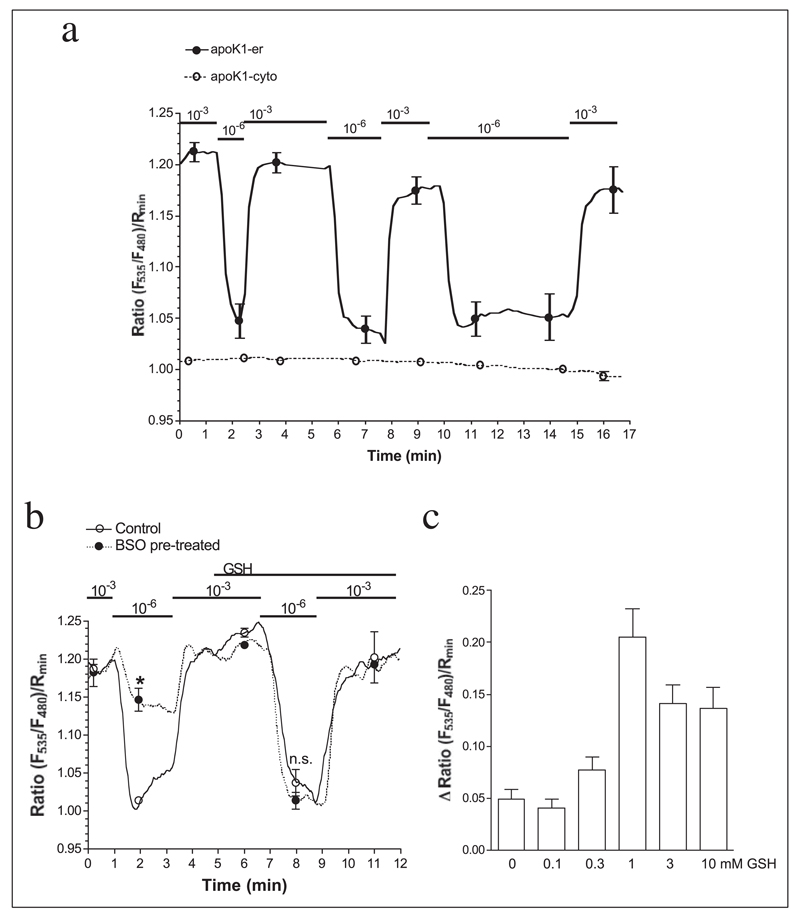

The kinetics of Ca2+-dependent FRET appearance and disappearance in apoK1-er was evaluated in permeabilized cells, while intraluminal Ca2+ was changed rapidly (within 0.2 min from 1 µm to 1 mm free Ca2+, Fig. 4a). Herein, the on- and off-set kinetics of this sensor were calculated and revealed similar association and dissociation kinetics of apoK1-er (τon = 0.244 and τoff = 0.249 min) that was comparable to that of YC4er (Fig. 3a). Considering such on/off kinetics, we assume that FRET occurs upon the Ca2+-dependent binding of apoK1-er to the calreticulin-ERp57 complex that results in protein folding, whereas no FRET can be further measured once the sensor dissociates from the chaperone complex. In cells transiently expressing apoK1 in the cytosol (i.e. apoK1-cyto, Fig. 2a), no change in the fluorescence of the protein was found by switching from high to low Ca2+ conditions (Fig. 4a). Because under these conditions apoK1-cyto remained inside the cells, these data indicate that the predicted Ca2+-dependent protein shortening that facilitated the appearance of FRET between the flanking fluorophores needs the environment of the ER, presumably calreticulin and ERp57.

FIGURE 4. ApoK1-er but not apoK1-cyto showed Ca2+-dependent and redox-sensitive changes in its FRET efficiency as an indicator of Ca2+-modulated formation of protein disulfide bridges on the calreticulin-Erp57 complex in the endoplasmic reticulum.

a, cells expressing either apoK1-er (●, continuous lines, n = 9) or apoK1-cyto (○, dotted line, n = 8) were permeabilized with 10 µm ionomycin and 1.5 µm digitonin and free Ca2+ concentration was set to 10−3 or 10−6 m as indicated. b, folding of apoK1-er was sensitive to the redox state of the ER lumen. Cells were pretreated for 12 h in GSH-free medium in the absence (Control) or presence of 5 mm BSO. After permeabilization, the response to the reduction of intraluminal free Ca2+ concentration from 1 mm to 1 µm was recorded prior and after readdition of 1 mm GSH (Control, n = 5; BSO, n = 7). c, the sensitivity of apoK1-er to the redox state of the ER was assessed by measuring Ca2+-dependent FRET in the presence of various GSH levels in BSO pretreated permeabilized endothelial cells (n = 6–7).

To elucidate to what extent the redox state of the ER affects the Ca2+-dependent folding of apoK1-er, the effect of the reduction of intraluminal free Ca2+ from 1 mm to 1 µm was assessed in cells that were depleted from GSH by preincubation with 5 mm BSO for 12 h in the absence of GSH. In GSH-depleted cells, the Ca2+ sensitivity of apoK1-er was reduced and could be restored by elevation of intraluminal GSH (Fig. 4b). The concentration dependence of apoK1-er revealed an optimum around 1 mm intraluminal GSH (Fig. 4c).

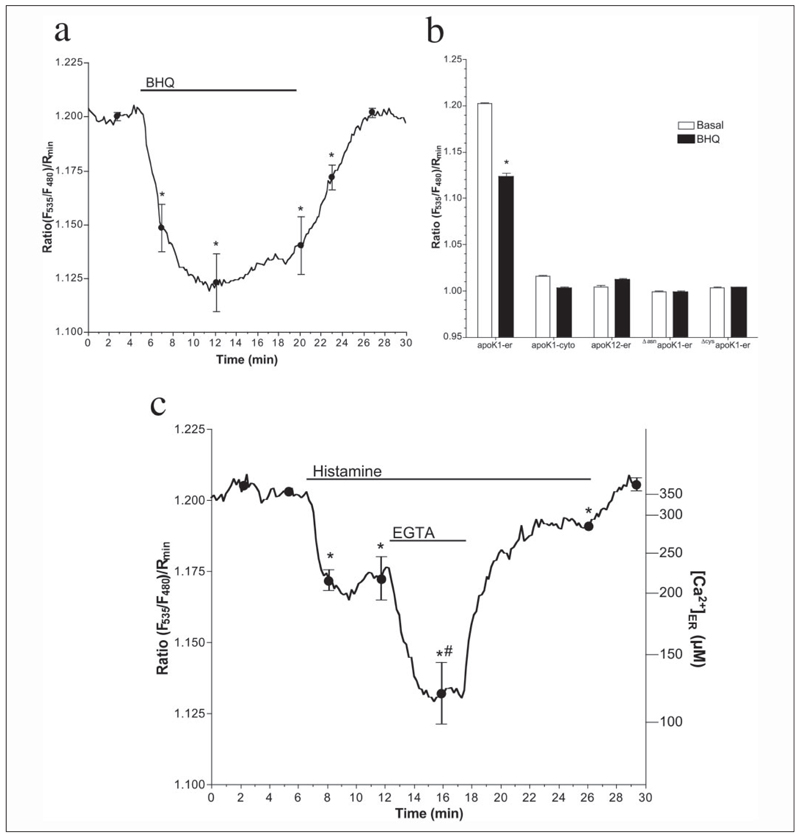

Exhaustive ER depletion by 15 µm BHQ (16, 28, 29), an inhibitor of sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPases (SERCAs), resulted in a strong reduction the FRET signal of apoK1-er and, to a lesser extent, that of apoK2-er (data not shown) but not that of apoK1-cyto (Fig. 5a). Moreover, in cells expressing apoK12-er and the mutants ΔasnapoK1-er and ΔcysapoK1-er, which were designed to avoid either protein folding (ΔasnapoK1-er and ΔcysapoK1-er) or FRET (apoK12-er), no effect of BHQ was observed (Fig. 5b).

FIGURE 5. ApoK1-er can be utilized as an intraluminal Ca2+ sensor in the endoplasmic reticulum.

a, as indicated, 15 µm BHQ was added to cells expressing apoK1-er (n = 10). b, effect of exhaustive Ca2+ depletion of the ER by 15 µm BHQ in cells expressing apoK1-er (n = 10) or the control constructs apoK1-cyto (n = 14), apoK12-er (n = 12), ΔasnapoK1-er (n = 9), or ΔcysapoK1-er (n = 18). Intraluminal Ca2+ concentration was expressed as the normalized FRET signal Ratio (F535/F480)/Rmin. c, endothelial cells were transiently transfected with apoK1-er. After 48 h, cells were mounted onto a deconvolution imaging microscope (16, 17, 31, 39) and perfused with physiological saline. As indicated, cells were stimulated with 100 µm histamine followed by a period in which extracellular Ca2+ was removed. Intraluminal Ca2+ concentration was expressed as the normalized FRET signal Ratio (F535/F480)/Rmin (left legend) and µm free Ca2+ (right legend) calculated by using the equation curve provided in Fig. 3. Data present the mean ± S.E. (n = 9). *, p < 0.05 versus baseline. #, p <0.05 versus in the presence of histamine in Ca2+-containing solution.

To further test the sensor for measurements of [Ca2+]ER under physiological conditions, human endothelial cells were transiently transfected with apoK1-er. In the presence of extracellular Ca2+, stimulation with 100 µm histamine resulted in partial ER depletion that was more pronounced by removal of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 5c). Readdition of extracellular Ca2+ resulted in recovery of the ER Ca2+ content despite continuous presence of the agonist and returned to basal level after histamine washout (Fig. 5c). These experiment resembles data obtained previously using YC4er (30) and, thus, confirm the suitability of apoK1-er for dynamic measurements of [Ca2+]ER in single living cells.

DISCUSSION

The approach for monitoring [Ca2+]ER by the visualization of Ca2+-dependent changes of protein structure presented herein matches the most prominent advantages of existing techniques, whereas it is not claimed that this new technique replaces them but may provide further important information. Because of the fast on/off kinetics, apoK1-er allows measurements of [Ca2+]ER with a similar time resolution normally achieved by conventional Ca2+ imaging techniques. Thus, dynamic regulation of intraluminal Ca2+ signaling can be assessed even under fast fluctuations of cellular/ER Ca2+ concentration and, at least with the experimental setup used in this study, time resolution was only restricted by the limitations in detection efficiency of the system rather than by the kinetics of the sensor. Second, apoK1-er, like the cameleons, is not irreversibly consumed by Ca2+, and thus, [Ca2+]ER can be repetitively monitored in one given cell under various conditions, and long term measurements are possible. Third, as apoK1-er is suitable for use in high resolution microscopy it allows the analysis of [Ca2+]ER in a subset of the ER in one given cell. Fourth, in contrast to the cameleons, which compete with the constitutive calmodulin for their effector proteins, the sensing properties of apoK1-er are actually the result of its interaction with constitutive chaperons. Fifth, as shown in Fig. 2, the utilization of apoK1-er as an Ca2+ sensor for the ER is not affected by co-expressed with additional e.g. DsRed-labeled proteins. Thus, apoK1-er is suitable for studies that are designed to follow spatial Ca2+ signaling in the ER simultaneously with e.g. mitochondrial movement (16, 31).

Moreover, compared with the existing genetically encoded Ca2+ sensors for the ER, apoK1-er offers also considerable advantages. As it follows the activity of constitutive Ca2+-binding proteins in the ER (i.e. calreticulin), apoK1-er perfectly monitors physiological Ca2+ fluctuations in the ER environment. Notably, the observed reduction of apoK1-er FRET by BHQ reached ~70% FRET reduction compared with that found at the removal of extracellular Ca2+ in ionomycin-permeabilized cells. These data are in line with the Ca2+-sensitivity curve obtained for apoK1-er (Fig. 3c, left panel) that indicates that the concentration for Ca2+ to regulate apoK1-er folding ranges between 10−5 and 10−3 M free Ca2+, which is in the physiological range of the intraluminal ER Ca2+ concentration (27, 32).

Notably, in the presence of extracellular Ca2+, endothelial cells are capable to retain most of the Ca2+ content of ER even upon stimulation with 100 µm histamine because of strong Ca2+ refilling that is fueled by Ca2+ entry (Fig. 5, Ref. 30). Under such conditions, the drop of apoK1-er FRET was 36% of that achievable with histamine in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ and, thus, was almost 1.6-fold higher as if conventional YC4er was used in the same set of experiments (30). This enhanced sensitivity of apoK1-er is because of its lower apparent KD (i.e. 124.2 (120.7–127.7) µm, Fig. 3c, left panel) compared with YC4er. Importantly, in the physiological range of the ER Ca2+ concentration (i.e. 10–700 µm), apoK1-er exhibits a more steep Ca2+ dependence compared with YC4er and thus, may be even more sensitive to small Ca2+ changes/fluctuations inside the ER (Fig. 3c).

These characteristics are very close to D1ER that has been recently developed and provides outstanding suitability for measurements of [Ca2+]ER (14). Nevertheless, although D1ER is an excellent tool for biological research, it shares the disadvantage of incorporating an additional Ca2+-binding protein into the lumen of the ER with the Ca2+ sensors introduced so far and, thus, also elevates ER Ca2+-buffering capacity inside this organelle. Because such intervention enhances the overall Ca2+ storage capacity of the ER, it may secondarily affect Ca2+-mediated functions inside the ER (33). Moreover, elevating the Ca2+ buffering capacity of ER might influence intraluminal Ca2+ homeostasis and interorganelle Ca2+ signaling to mitochondria for example (15). Particularly in view of the proposed regulatory function of intraluminal Ca2+ for activation/termination of the so-called capacitative Ca2+ entry (34–36) and the importance of interorganelle Ca2+ cross-talk (16, 27, 37), Ca2+ sensors that affect intraluminal Ca2+ buffer capacity might be critical. Importantly, apoK1-er does not contain a Ca2+-binding domain but interacts with constitutive calreticulin/ERp57 in a Ca2+-dependent manner and, thus, measures ER Ca2+ concentration by monitoring the action of luminal Ca2+ on its constitutive effector proteins. Therefore, this property can be further utilized to monitor the free Ca2+ concentration inside the ER without manipulating the Ca2+-buffering/storage capacity of this organelle. On the other hand, although apoK1-er lacks the cysteines essential for binding to apoB (38), a modulation of the properties of the sensor by binding ER components other than calreticulin/ERp57 cannot be excluded.

In addition, comparison of the pH sensitivities of D1ER and apoK1-er indicate that the latter one can be significantly improved by exchanging its fluorophores to more stable ones. Therefore, such improved apoK1-er variants are currently constructed in our laboratory.

Accordingly, the concept to visualize [Ca2+]ER by FRET based on the Ca2+-dependent structural shortening of a designed substrate protein for the given Ca2+-dependent protein folding machinery shares the intriguing advantages of the existing sensors for measuring [Ca2+]ER, provides excellent targeting into the ER, and offers a Ca2+ sensitivity that is suitable for Ca2+ measuring in the ER environment but does not contain a Ca2+-binding domain that may affect cellular/subcellular/interorganelle Ca2+ signaling. These unique characteristics may make this new type of sensor the first choice in studies where the contribution of ER Ca2+ content to cellular, subcellular, and/or interorganelle Ca2+ homeostasis or Ca2+-dependent processes in the cell has to be assessed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. R. Y. Tsien and A. Miyawaki for YC4er, YC2.1 and D1ER, Dr. C. J. S. Edgell for the EA.hy926 cells, Dr. S. Frank for the apo(a) templates, and Beatrix Petschar and Anna Schreilechner for their excellent technical assistance. The Department of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry is a member of the Institutes of Basic Medical Sciences (IBMS) at the Medical University of Graz and was supported by the infrastructure program (UGP4) of the Austrian Ministry of Education, Science and Culture.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: ER, endoplasmic reticulum; GFP, green fluorescent protein; HEK, human embryonic kidney; FRET, fluorescence resonance energy transfer; BSO, dl-buthionine-[SR] sulfoximine; BHQ, 2,5-di-(tert-butyl)-1,4-hydroquinone; [Ca2+]ER, free Ca2+ concentration of the ER; MES, 2-morpholinoethanesulfonic acid; YC4er, ER-targeted yellow cameleon 4.

References

- 1.Szabadkai G, Rizzuto R. FEBS Lett. 2004;567:111–115. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frieden M, Graier WF. J Physiol. 2000;524:715–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00715.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frieden M, Malli R, Samardzija M, Demaurex N, Graier WF. J Physiol. 2002;540:73–84. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.017053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corbett EF, Michalak KM, Oikawa K, Johnson S, Campbell ID, Eggleton P, Kay C, Michalak M. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27177–27185. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002049200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tse A, Tse FW, Hille B. J Physiol. 1994;477:511–525. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montero M, Brini M, Marsault R, Alvarez J, Sitia R, Pozzan T, Rizzuto R. EMBO J. 1995;14:5467–5475. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Persechini A, Lynch JA, Romoser VA. Cell Calcium. 1997;22:209–216. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(97)90014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Romoser VA, Hinkle PM, Persechini A. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13270–13274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.13270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyawaki A, Griesbeck O, Heim R, Tsien RY. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2135–2140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyawaki A, Llopis J, Heim R, McCaffery JM, Adams JA, Ikura M, Tsien RY. Nature. 1997;388:882–887. doi: 10.1038/42264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagai T, Sawano A, Park ES, Miyawaki A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3197–3202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051636098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heim N, Griesbeck O. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:14280–14286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demaurex N, Frieden M. Cell Calcium. 2003;34:109–119. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palmer AE, Jin C, Reece JC, Tsien RY. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;101:17404–17409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408030101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnaudeau S, Frieden M, Nakamura K, Castelbou C, Michalak M, Demaurex N. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46696–46705. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202395200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malli R, Frieden M, Osibow K, Zoratti C, Mayer M, Demaurex N, Graier WF. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44769–44779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302511200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paltauf-Doburzynska J, Malli R, Graier WF. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;44:424–437. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000139449.64337.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graier WF, Grubenthal I, Dittrich P, Wascher TC, Kostner GM. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;294:221–229. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00534-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White AL, Guerra B, Lanford RE. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5048–5055. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.5048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J, White AL. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8993–9000. doi: 10.1021/bi000027v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lippincott-Schwartz J, Snapp E, Kenworthy A. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:444–456. doi: 10.1038/35073068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zoratti C, Kipmen-Korgun D, Osibow K, Malli R, Graier WF. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;140:1351–1362. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Helenius A, Aebi M. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:1019–1049. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Helenius A, Aebi M. Science. 2001;291:2364–2369. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5512.2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kostner GM, Ibovnik A, Holzer H, Grillhofer H. J Lipid Res. 1999;40:2255–2263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frickel EM, Frei P, Bouvier M, Stafford WF, Helenius A, Glockshuber R, Ellgaard L. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18277–18287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314089200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnaudeau S, Kelley WL, Walsh JV, Jr, Demaurex N. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29430–29439. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103274200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graier WF, Posch K, Wascher TC, Kostner GM. Horm Metab Res. 1997;29:622–626. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dolor RJ, Hurwitz LM, Mirza Z, Strauss HC, Whorton AR. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:C171–C181. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.1.C171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malli R, Frieden M, Trenker M, Graier WF. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12114–12122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409353200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malli R, Frieden M, Osibow K, Graier WF. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:10807–10815. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212971200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corbett EF, Michalak M. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:307–311. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01588-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miyakawa T, Maeda A, Yamazawa T, Hirose K, Kurosaki T, Iino M. EMBO J. 1999;18:1303–1308. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nilius B, Droogmans G, Wondergem R. Endothelium. 2003;10:5–15. doi: 10.1080/10623320303356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nilius B, Droogmans G, Gericke M, Schwarz G. EXS. 1993;66:269–280. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-7327-7_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nilius B. Cell Calcium. 2003;33:293–298. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rizzuto R, Pinton P, Carrington W, Fay FS, Fogarty KE, Lifshitz LM, Tuft RA, Pozzan T. Science. 1998;280:1763–1766. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5370.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sommer A, Gorges R, Kostner GM, Paltauf F, Hermetter A. Biochemistry. 1991;30:11245–11249. doi: 10.1021/bi00111a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paltauf-Doburzynska J, Frieden M, Spitaler M, Graier WF. J Physiol. 2000;524:701–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00701.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]