Abstract

Gold standard in therapy of superficial, non-muscle invasive urothelial tumors is transurethral resection followed by intravesical instillation therapies. However, relapse is commonly observed and therefore new therapeutic approaches are needed. Application of 213Bi-immunoconjugates targeting EGFR had shown promising results in early tumor stages. The aim of this study was the evaluation of fractionated application of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb in advanced tumor stages in a nude mouse model. Luciferase-transfected EJ28 human bladder carcinoma cells were instilled intravesically into nude mice following electrocautery. Tumor development was monitored via bioluminescence imaging. One day after tumor detection mice were treated intravesically either 2 times with 0.93 MBq or 3 times with 0.46 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb. Therapeutic efficacy was evaluated via overall survival and toxicity toward normal urothelium by histopathological analysis. Mice without treatment and those treated with the native anti-EGFR-MAb showed mean survivals of 65.4 and 57.6 d, respectively. After fractionated treatment with 0.93 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb animals reached a mean survival of 141.5 d and 33% of the animals survived at least 268 d. Fractionated treatment with 0.46 MBq 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb resulted in a mean survival of 131.8 d and 30% of the animals survived longer than 300 d. Significant differences were only observed between the control groups and the group treated twice with 0.93 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb. No toxic side-effects on the normal urothelium were observed even after treatment with 3.7 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb. The study demonstrates that the fractionated intravesical radioimmunotherapy with 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb is a promising approach in advanced bladder carcinoma.

Keywords: α-emitter, bladder cancer, EJ28 cells, histopathology, immunotherapy, targeted treatment, toxicity

Abbreviations

- BCG

Bacillus Calmette-Guárin

- DAB

3,3'-diaminobenzidine

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- H&E

hematoxylin & eosin

- LET

linear energy transfer

- MAb

monoclonal antibody

- TUR

transurethral resection.

Introduction

Bladder cancer is one of the most common malignancies worldwide. Every year approximately 350,000 cases of bladder cancer are diagnosed worldwide and over 130,000 patients die on the consequences of the disease.1 The highest rates of bladder cancer are found in developed countries. Men tend to have a fourfold higher risk to suffer from bladder cancer than women and the average age at tumor diagnosis is 65 years.2 There are several risk factors for bladder cancer including genetic disposition, smoking and occupational exposure to aromatic amines and special azodyes.3 90% of bladder carcinomas are pathogenetically assigned to urothelial cell carcinomas, 5% to squamous cell carcinomas and 1–2% to adenocarcinomas. 75% of newly diagnosed urothelial carcinomas are non-muscle-invasive.4 The leading symptom is painless micro- or macro-hematuria although the disease is completely asymtomatic in 25% of all cases.5 Gold standard of diagnosis is cystoscopy complemented by white light endoscopy, urine cytology, excretory urogram analysis, sonography as well as analysis of biomarkers.4,6,7

Gold standard in therapy of superficial, non-muscle-invasive urothelial tumors is transurethral resection (TUR). To reduce the risk of recurrence caused by tumor cells released during TUR, adjuvant intravesical instillation therapies such as chemotherapy with mitomycin C, epirubicin, or doxorubicin are performed within 24 hours after TUR. Moreover, immunotherapy with Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) is administered 4 weeks after TUR at the earliest.8,9 The risk of recurrence may be reduced initially, but 75% of patients are affected by severe side effects, restricting their quality of life and up to 54% of patients suffer from relapse within 5 years.4,8,9 Therefore new adjuvant therapeutic approaches after TUR are urgently needed.

Instillation therapies using chemotherapeutic drugs unselectively affect all proliferative cells and therefore induce toxic side effects. In contrast, targeted cancer therapies are directed specifically against tumor cells and therefore have less undesired side effects on normal cells. Several biological agents such as gefetinib, sorafenib and lapatinib have been investigated in targeted treatment of metastatic bladder cancer. However, therapeutic efficacy of these compounds administered as single agents has not turned out satisfactory.10

In immunotherapy, monoclonal antibodies targeting antigens expressed on cancer cells are used as carriers for cytotoxic drugs. In radioimmunotherapy, radionuclides emitting α- or β-particles are used as therapeutic compounds.11-14 Alpha-particles possess high kinetic energies (4–9 MeV) combined with short ranges in tissue (28–100 μm), and therefore the energies released per distance (linear energy transfer, LET) are comparatively high (50-230 keV/μm). Accordingly, α-particles efficiently eradicate single tumor cells and small cell clusters.15-17 Moreover, irradiation with α-particles can stimulate adaptive immunity.18

Because the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is overexpressed in 86% of urothelial carcinomas,19 it represents an ideal target for locoregional radioimmunotherapy. As has been shown in a previous study, the anti-EGFR antibody matuzumab labeled with the α-emitter 213Bi binds to EGFR overexpressing EJ28 human bladder carcinoma cells with high affinity.20 Therapeutic efficacy of 213Bi-anti-EGFR immunoconjugates was assayed in an orthotopic nude mouse model following intravesical instillation of human EJ28 bladder cancer cells. At different times after cell inoculation mice were treated with a single administration of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-mAb. While treatment at early time points (1 h, 7 d after tumor cell inoculation) demonstrated significant prolongation of survival, it proved less successful in advanced tumor stages (14 d after cell instillation).20

Therefore, in the present study tumor development, as verified by non-invasive bioluminescence imaging, and survival were evaluated in advanced urothelial carcinomas after administration of 2 different fractionated intreavesical therapy regimens using 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb. Another aim of this study was to demonstrate that intravesical radioimmunotherapy with the α-emitter 213Bi does not produce toxic side effects. For this purpose the urothelia of murine bladders were subjected to histopathological analysis 300 d after administration of different activities of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb.

Results

213Bi radiolabeling of anti-EGFR-MAb

Labeling of CHX-A”-DTPA chelated anti-EGFR-MAb (matuzumab; 100 μg) with 213Bi activities varying between 20.5 and 200.9 MBq resulted in specific activities of 0.22–1.98 MBq/μg antibody. The lowest and highest specific activities correspond to one of 4,545 and one of 505 anti-EGFR-MAb molecules labeled with the α-emitter 213Bi, respectively. Purity and stability of the 213Bi-anti-EGFR immunoconjugates were in accordance with results described previously.20

Orthotopic xenograft mouse model

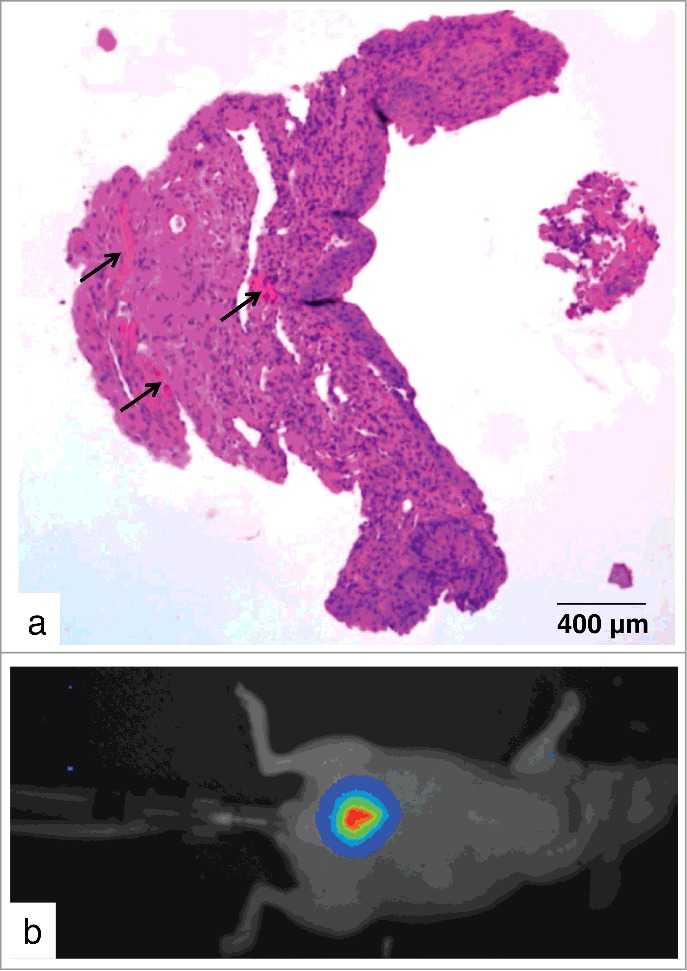

Successful electrocauterization could be demonstrated by histopathological examination of the urothelium of a murine bladder showing lesions with conglomerates of erythrocytes (Fig. 1a). Moreover, successful inoculation of EJ28-luc cells into the murine bladder could be shown via bioluminescence imaging (Fig. 1b). Intravesical inoculation of EJ28-luc cells after gentle cauterization of the bladder resulted in tumor development in 61.5% of all animals. Only animals that had developed an urothelial tumor, as manifested via bioluminescence imaging at different time points after cell instillation, were subjected to treatment with 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb.

Figure 1.

Orthotopic xenograft mouse model. (a) H&E stained paraffin section of the urothelium of a murine bladder immediately after electrocauterization shows lesions with conglomerates of erythrocytes (arrows). (b) Bioluminescence image in pseudocolors taken directly after instillation of 2 × 106 EJ28-luc cells in the urinary bladder.

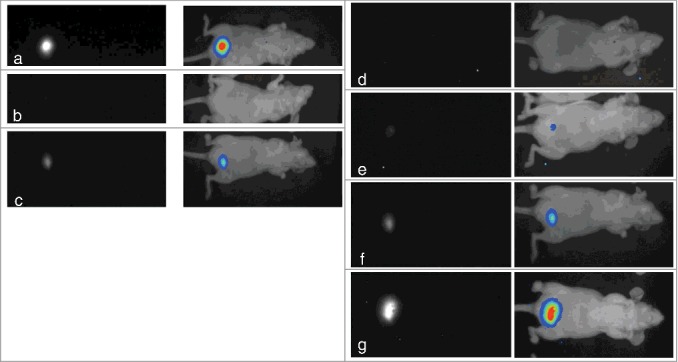

Tumors were detected for the first time between 7 and 43 days after tumor cell inoculation. Precisely, after 7 d, 14 d, 21 d and 43 d, 17%, 41%, 27% and 15% of all tumors could be visualized via bioluminescence imaging, respectively. Figures 2a-c illustrates varying tumor growth in 3 animals 21 days after inoculation of 2 × 106 EJ28-luc cells, respectively. Figures 2d-g demonstrate tumor development via bioluminescence imaging in the same mouse at days 7, 14, 21 and 28 after cell instillation.

Figure 2.

Bioluminescence images of tumor development after intravesical instillation of EJ28-luc cells. (a-c) Different tumor development in 3 mice 21 days after injection of 2 × 106 EJ28-luc cells. (d-g) Tumor development in the very same mouse 7 (d), 14 (e), 21 (f) and 28 (g) days after instillation of 2 × 106 EJ28-luc cells. black-white mode (left), pseudocolors (right).

Concurrence of tumor detection via bioluminescence imaging and histological analysis

In animals that showed no bioluminescence signal in the bladder following instillation of EJ28-luc tumor cells, also no signs of tumor could be detected via histological analysis in cryosections of the urothelium. Tumors which emitted minimal bioluminescence signals could be detected in the black and white mode only. The histological examination of corresponding tumors showed a slight disturbance of cell texture and cell layers of the urothelium as well as slight cell- and nucleus-atypias. These tumors were classified as low-grade carcinomas. Tumors that were identified as moderate carcinomas through bioluminescence imaging could be confirmed as tumors of intermediate size also by histological analysis. Cell layers could still be observed showing moderate atypias with polymorphisms of cells and nuclei. These tumors were classified as high-grade carcinomas and identified as carcinoma in situ (data not shown).

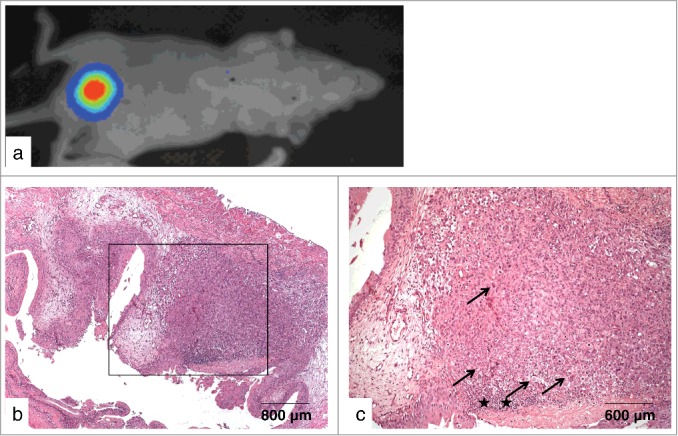

Finally, widespread dissemination of tumor cells in the bladder as concluded from an intensive bioluminescence imaging signal (Fig. 3a) could also be confirmed histopathologically (Figs. 3b, c). The cryosections showed large tumor cell clusters of EJ28-luc cells associated with the destruction of normal cell layers of the urothelium. Furthermore, highly proliferative carcinoma cells exhibited innumerable hyperchromatic atypias in the cells and nuclei as well as during mitosis. Because the tumor cells grew up to the submucosa but not into the muscularis, the tumor was also classified as carcinoma in situ.

Figure 3.

Non-invasive high-grade human urothelial carcinoma in the murine bladder. (a) Bladder tumor as detected via bioluminescence imaging 21 d after instillation of EJ28-luc cells. (b-c) Frozen section of the corresponding bladder - overview (b), section (c) - showing large tumor cell clusters along with the destruction of cell layers of the urothelium and tumor cells exhibiting innumerable hyperchromatic cellular and nuclear atypias (arrows) as well as an ulcer with infiltration of leucocytes (asterisks).

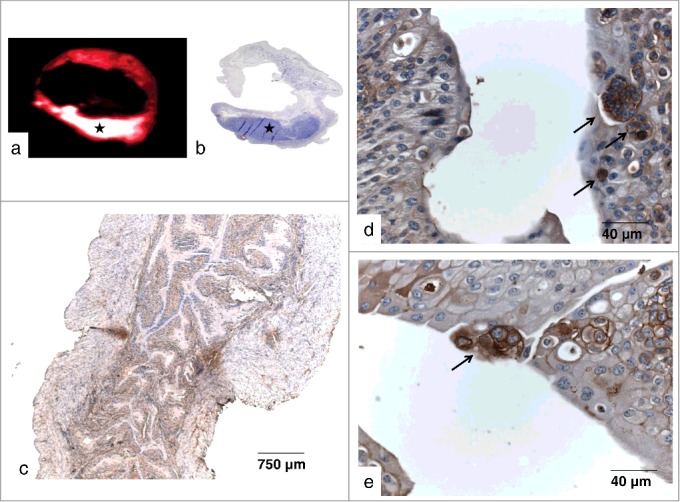

Detection of human EJ28 xenografts in the murine bladder via immunological methods

After non-invasive detection of xenograft bladder tumors via bioluminescence imaging, paraffin sections of murine bladders were incubated with 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb as described and were then analyzed using the μ-IMAGER. Via microautoradiography location of EGFR-positive EJ28 cells could be demonstrated within the murine bladder thus verifying that 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb immunoconjugates selectively bind to bladder cancer cells in vivo. Location of bladder cancer cells was confirmed by H&E staining of bladder sections (Figs. 4a, b). Moreover, EJ28 cells overexpressing EGFR could be detected in the urothelia of injected animals via immunohistochemistry using bladder cryosections. Selective staining of EJ28 cells was performed by incubation of bladder cryosections with anti-EGFR-MAb, anti-IgG coupled with horseradish-peroxidase and the substrate DAB (Figs. 4c-e).

Figure 4.

EGFR overexpression in bladder xenografts. (a) Autoradiograhic detection of EJ28-luc xenografts in a paraffin section of the murine bladder following incubation with 213Bi-anti-EGFR-mAb (asterisk). (b) H&E stained correlate confirming location of EJ28-luc bladder cancer cells (asterisk). (c-e) Immunohistochemical detection of EGFR-overexpressing EJ28-luc xenografts in frozen sections of the murine bladder. Binding of the anti-EGFR-MAb was visualized as a brownish color via a secondary HRP-conjugated anti IgG antibody and the HPR-substrate DAB. (c) overview, (d, e) sections showing tumor cells (arrows) embedded in normal, blue-stained tissue.

Efficacy of fractionated 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb therapy

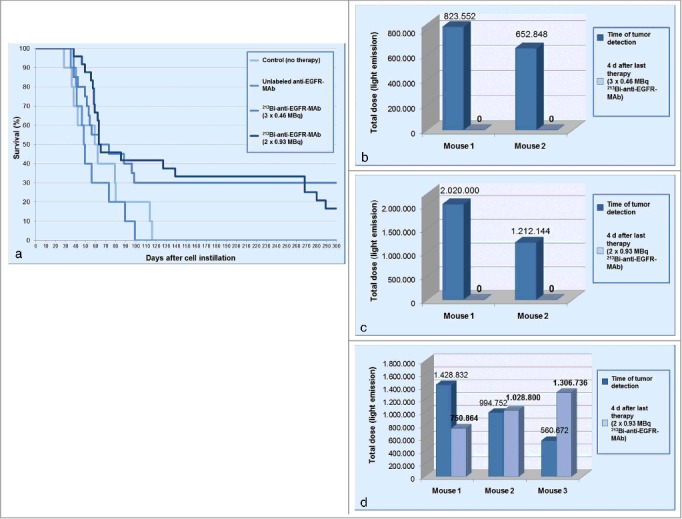

Mean survival was clearly longer in the 2 treatment groups compared with the 2 control groups. While in the untreated group and in the group treated with unlabeled anti-EGFR-MAb animals survived 65.4 d and 57.6 d on average, respectively, in the groups treated 3 times with 0.46 and twice with 0.93 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb mean survival prolonged to 131.9 d and 141.5 d, respectively. Moreover, in the group treated 3 times with 0.46 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb 55% of the animals showed no tumor in bioluminescence imaging 7 d after the third treatment. However in 25% of these animals tumors progressed despite treatment. In the group treated twice with 0.93 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb similar results were observed with regard to tumor development 7 d after the second treatment: in 50% of the animals no tumor could be detected via bioluminescence imaging, while in 17% tumors had progressed despite treatment. In the end fractionated treatment with 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb resulted in 30% of animals surviving longer than 300 d (3 × 0.46 MBq) and 33.3% of animals surviving longer than 260 d (with 16.7% of them surviving longer than 300 d) (2 × 0.93 MBq) (Fig. 5a). In contrast, in the control groups no animal survived longer than 116 days. Nevertheless statistical analysis revealed significance (p < 0.05) only between the untreated group and the group treated twice with 0.93 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb as well as the group treated with the unlabeled anti-EGFR-MAb and the group treated twice with 0.93 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb.

Figure 5.

Therapeutic efficacy of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb treatment. (a) Kaplan–Meier plot illustrating survival of animals with intravesical tumors: untreated controls; intravesical treatment with unlabelled anti-EGFR-MAb (1 μg each) at the day of tumor detection and at days 4 and 8 thereafter; intravesical treatment with 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb 3 times with 0.46 MBq at the day of tumor detection and at days 4 and 8 thereafter or twice with 0.93 MBq at the day of tumor detection and at day 7 thereafter. (b-d) Light emissions over ROIs of intravesical tumors before and after therapy with 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb. Treatment with 3×0.46 (b) and 2 × 0.93 MBq (c) of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb in 2 selected mice, respectively, resulted in complete eradication of tumors as analyzed 4 days after the last therapeutic application. (d) demonstrates that treatment with 2 × 0.93 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb could also result in partial response, stable disease or progressive disease.

Additionally, light emissions from tumors of selected mice were quantified over ROIs before and after therapy. The quantification of the light emissions again indicates that some tumors were completely eradicated by 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb treatment, whereas others were only slightly affected or even increased after therapy. As shown in Fig. 5, no bioluminescence signal could be detected in selected animals 4 days after the third treatment with 0.46 MBq as well as 4 days after the second treatment with 0.93 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb (Figs. 5b, c). In contrast, other selected mice demonstrated partial remission, stable disease or even tumor progression 4 days after the second treatment with 0.93 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb (Fig. 5d).

Effects of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb instillation on bladder urothelium

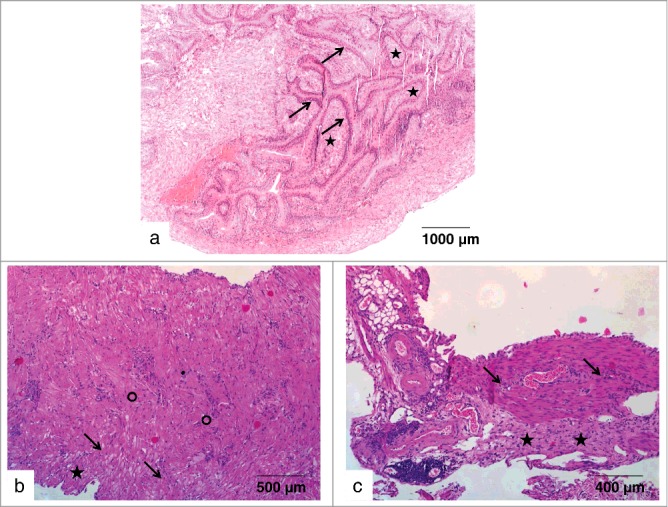

To evaluate whether treatment with 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb might damage the normal bladder urothelium, mice without former instillation of tumor cells were intravesically injected with different activities of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb. 300 d after treatment with 0.46 MBq 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb (3 times with a 4 days interval), and 146 d after treatment with 1.85 MBq 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb (2 times with a 7 days interval), or 3.7 MBq 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb (2 times with a 7 days interval), respectively, the bladders of the animals (n = 5 per group) were subjected to histopathological analysis. All animals displayed no conspicuous symptoms during the observation periods. The histopathological analyses proved normal urothelium with no abnormalities of the cells and no evidence of inflammatory processes or cell destruction (Figs. 6a-c).

Figure 6.

Effects of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb on normal bladder tissue. (a) Urothelium of a murine bladder 300 d after administration of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb (3×0.46 MBq). The bladder section does not show any pathological abnormalities: tunica mucosa with urothelium (arrows), lamina propria mucosae (asterisks). (b-c) Urothelia of 2 murine bladders without any pathological abnormalities; (b-c) Bladder sections 146 d after 2-time application of 1.85 MBq (b) or 3.7 MBq (c) of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb (within 7 d, respectively). The sections show the multi-row urothelium (asterisks) with submucosa (arrows) and mucosa (circle).

Discussion

Recurrence of urothelial carinoma after TUR is caused by adhesion of disseminated tumor cells on urothelial lesions. Adjuvant intravesical chemotheraphy and BCG-instillation eradicate cancer cells and thus can inhibit cell adhesion. Both these therapies are associated with various side effects and risk of relapse is still high. Therefore, we aimed to examine the therapeutic efficacy of fractionated intravesical instillation of the radioimmunoconjugate 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb in an orthotopic mouse model. In this model the murine urothelium was cauterized followed by instillation of human urothelial cancer cells to imitate TUR. As soon as tumors were first detected through bioluminescence imaging, fractionated therapy with 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb was initialized. The urinary bladder is suited for instillation therapy due to its anatomical and physiological characteristics. Nevertheless the establishment, visualization and therapy of the urothelial carcinoma in a mouse model presented several challenges.

A central issue in every orthotopic urothelial cancer model is the success rate of tumor establishment which is dependent on pretreatment of the urothelium, tumorigenicity of the cell line, quantity of instilled cells and adhesion time. Although these parameters were kept constant, tumor development still varied in our study. This could be explained by slight differences in the process of cauterization followed by differences in cell adhesion in the individual animals treated.

The rates of tumor establishment in different cancer models are described to vary between 30% and 100% depending on the instillation procedure and the parameters mentioned above.21 After transurethral inoculation the rate of tumor establishment is generally lower than after intramural injection, where carcinoma cells are injected directly into the abdominal dissected mucosa of the murine bladder,22 however the transurethral method is less invasive. Furthermore the direct injection of tumor cells often leads to muscle-invasive and metastasized carcinomas and causes complications resulting from surgery.23,24 Transurethral instillation of bladder carcinoma cells via a catheter results in superficial tumors in up to 80%, however the tumor incidence is barely reproducible because of the glycosaminoglycan-layer on the surface of the urothelium which functions as a natural protective barrier against external substances and cell adhesion.25 Different rates of tumor establishment have been reported following cauterization of the bladder, ranging from 54% using MBT-683 cells to 100% with murine bladder cancer MB49.24,26 Moreover, the number of administered cells is relevant to tumor development. Increase of 2.5 × 105 to 2 × 106 cells incre-ased the rate of tumor establishment from 30% up to 93%.21,23 In the present study 2 × 106 EJ28-luc cells in 50 μl RPMI-medium were instilled intravesically and catheters left in the murine bladders for the duration of 2.5 h which lead to tumor establishment in 61.5%. No overexpansion of bladders and therefore no tumor growth in the upper urinary tract were observed.

Bioluminescence imaging represents a very sensitive, non-invasive technique for monitoring of tumor development and of therapeutic efficacy.27 In the present study the cell line EJ28 was transfected with firefly-luciferase (EJ28-luc) to monitor therapeutic efficacy of treatment with 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb. Analysis of regions of interest (ROIs) before and after therapy permits the quantification of therapeutic efficacy.28

Though we could demonstrate that there is a good correlation between the strength of the bioluminescence signal and the extension of the tumor in the bladder (Fig. 3), strengths of bioluminescence signals obviously did not generally reflect actual tumor sizes. As shown in Fig. 5c, a tumor representing a light emission of 1.212.144 units was completely eradicated by 2 consecutive treatments with 0.93 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb. In contrast tumors of obviously smaller size before the first treatment, as concluded from the light emissions over ROIs (944.752 and 560.672 units; Fig. 5d), were not eradicated by the 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb treatment. Accordingly, we presume that light emissions over ROIs not unequivocally represent the actual tumor size, i.e. identical values do not represent identical tumors in any case.

Therefore, bioluminescence imaging mainly can be used as a qualitative technique with limitations in the quantification of more advanced tumor stages.29 In our study light emissions over ROIs were used only to analyze tumor development of one and the same animal before and after treatment (Fig. 5). Nevertheless, the advantages of using bioluminescence imaging surpass its limitations in terms of monitoring therapeutic efficacy.28

Pathological overexpression of EGFR may lead to uncontrolled cell proliferation, increased angiogenesis and decreased apoptosis and therefore promote malignant growth. Additionally EGFR has been shown to correlate with tumor progression, advanced tumor stages and poor clinical prognosis.30 EGFR is overexpressed in 86% of patients suffering from urothelial carcinoma.19 Moreover, the EGFR-signaling pathway was identified as one of the central mediators of the tumorigenic process through the activation of its endogenous tyrosine kinase activity. Therefore, the blockade of the receptor via EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as gefitinib and erlotinib is a promising therapeutic approach.31 However, administration of monoclonal antibodies targeting EGFR in combination with chemotherapy did not improve therapeutic efficacy over chemotherapy alone in advanced urothelial carcinoma.32 In our study, treatment with the native anti-EGFR-MAb (1 μg) also did not show any therapeutic efficacy.

EGFR served as the target for treatment with 213Bi-anti-EGFR-immunoconjugates in the approach described here. We could demonstrate that EGFR overexpression of human EJ-28-luc cells was also present in the murine bladder cancer model and that the 213Bi-anti-EGFR-immunoconjugates accumulate at the site of the location of the tumor cells, which is an important prerequisite for efficient therapy (Fig. 4). Moreover, targeted therapy with the α-emitter 213Bi has turned out as a promising therapeutic approach for different types of tumors.33

In our study nude mice bearing xenograft bladder tumors, as detected via bioluminescence imaging, were treated twice with 0.93 MBq 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb at the day of tumor detection and 7 d later or 3 times with 0.46 MBq 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb at the day of tumor detection, as well as 4 d and 8 d later. No matter what the therapeutic efficacy, these treatments did not cause any toxic side effects in terms of the normal urothelium. Even after intravesical injection of significantly higher activities of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb (2 × 1.85 MBq or 2 × 3.7 MBq) than those that were therapeutically effective, no pathological findings could be observed in the urothelium of tumor-free mice. These findings are in favor of the selective efficacy of the intravesical radioimmunotherapy of urothelial carcinoma with 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb.

In a previous study, mice received a single treatment with 0.93 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb 1 h, 7 d or 14 d after intravesical cell instillation. Treatment at 1 h and 7 d after cell instillation was very efficient, resulting in median survival times >300 d in 90% and 80% of animals, respectively. In contrast, treatment 14 d after cell instillation was significantly less successful, resulting in a median survival of 55 d, with only 40% of mice surviving more than >300 d.20 Reduced therapeutic efficacy might be obviously due to advanced tumor stages with extended volumes that are inappropriate for single treatment with short range α-emitters.

To produce relief, fractionated therapy with α-emitter immunoconjugates was assayed in the present study. The concept of fractionated therapy is based on the assumption that tumor nodules with diameters larger than the range of α-emitters can be eradicated step-by-step via consecutive elimination of the outer cell layers of a tumor nodule. Therefore, advanced tumors (i.e., between days 7 and 43 after tumor cell instillation), as detected via bioluminescence imaging, were treated twice with 0.93 MBq or 3 times with 0.46 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb. Comparison of these 2 groups receiving fractionated therapy with the group treated once with 0.93 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb 14 days after cell instillation analyzed in a previous study19 did not reveal significant differences in terms of overall survival.

Nevertheless, significant differences were observed between the control groups and the group treated twice with 0.93 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb, but not between control groups and the group treated 3 times with 0.46 MBq or between control groups and the group treated once with 0.93 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb. Accordingly, statistical dispersion as quantified via the interquartile range (ICR) was lowest in the fractionated treatment group treated twice with 0.93 MBq 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb and highest in the group treated once with 0.93 MBq 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb: 219 d (2 × 0.93 MBq), 250.5 d (3 × 0.46 MBq), 277 d (1 × 0.93 MBq). Because inside of the ICR there are 50% of all measured data, the ICR data suggest that fractionated treatment done twice with 0.93 MBq 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb is superior to single treatment with 0.93 MBq or fractionated treatment with lower activities (3 times with 0.46 MBq). Moreover, the data indicate that an increase of the number of treatment cycles with 0.93 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb could further increase therapeutic efficacy.

The details of the experimental design also suggest that fractionated therapy is superior to single administration: all animals that were treated with fractionated regimens had tumors, as visualized via bioluminescence imaging. Fractionated treatment with 213Bi-Anti-EGFR-MAb was initiated only after detection of tumor growth through bioluminescence imaging. In contrast, single treatment of animals with 0.93 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb 14 d after cell instillation was done without precedent verification of tumor growth. Because tumor growth rate turned out as 80% in the animal model used, some of the animals that survived >300 d might not have developed a tumor at the time of treatment.20

Efficacy of fractionated treatment of advanced tumors with 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb could possibly be further enhanced by additional treatment cycles and/or combined treatment with α-emitter (213Bi) and β-emitter anti-EGFR-MAb immunoconjugates. Due to their comparatively long penetration range in biological tissues, varying from 0.5 to 12 mm, β-emitters, such as the commonly used 90Y, 177Lu, 131I, 186Re and 67Cu, can induce cytotoxic effects in the interior of a large tumor nodule.14 Therefore, combined administration of α- and β-emitter anti-EGFR-MAb immunoconjugates might help to eradicate larger tumor nodules that are resistant to treatment with short range α-emitters only.

Experimental radioimmunotherapy of bladder cancer with 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb is a promising treatment option for early stage bladder cancer. Fractionated administration of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb could be effective even in the treatment of advanced stages. Therefore, treatment of bladder cancer patients with 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb could help to avoid ultima ratio cystectomy and thus significantly improve the quality of patients' lives. In an ongoing pilot study 7 patients suffering from carcinoma in situ were treated intravesically with 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb. Results by now look very promising thus confirming high therapeutic efficacy of 213Bi radioimmunotherapy in the animal model.

Materials and Methods

Transfection of EJ28 cells with luciferase

In order to non-invasively visualize tumor development, the cell line EJ28 (provided by the Department of Urology, TUM) was stably transfected with firefly luciferase.34 Transfected EJ28-luc cells were cultivated in RPMI, supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 1% nonessential amino acids, 100 IU/ml Penicillin, 100 μg/ml Streptomycin and 1 μg/ml geneticin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. For propagation adherent cells were harvested with 1 mM EDTA in phosphate-buffered saline.

Orthotopic xenograft model of human urothelial carcinoma

Six week old female Swiss nu/nu mice (Charles River, France) were housed in isolated and ventilated cages (5 mice per cage) for a minimum of 1 week prior to tumor cell instillation. Animals were kept at a mean temperature of 26°C and a humidity of 50-60% and food and water were provided ad libitum.

The human urothelial carcinoma xenograft was established orthotopically following gentle electrocautery as described20 with slight modifications. For cauterization, monopolar coagulation was applied for 1 s at 7 W using the Erbotom 70 cautery unit (Erbe, Tuebingen). Per mouse 12 lesions were created in the bladder. 2 × 106 EJ28-luc cells in 50 μl sterile RPMI were instilled into the bladder via a catheter and left to settle at the bladder wall for 2.5 h. A syringe connected to the external end of the catheter was used to prevent cell leakage. Mice were inspected daily for signs of illness.

Monitoring of tumor growth via bioluminescence imaging

Non-invasive bioluminescence imaging was performed once a week after instillation of EJ28-luc cells to monitor tumor development before and after therapy with 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb. For this purpose mice were injected intraperitoneally with of 20 μl of D-Luciferin (15 mg/ml) and 170 μl of ketamin/xylazin (100/5 mg/kg) and positioned in the dark box of the cooled charge-coupled device camera attached to a light intensifier unit (Hamamatsu). Bioluminescence images were recorded with exposure times of 180-280 s and pictures were processed using simple PCI software (Hamamatsu). Subsequently the light emissions were transformed into pseudocolors. Definition of regions of interest (ROIs) around each tumor allowed light emissions from tumor cells to be quantified by subtraction of background emissions. The collected data was statistically analyzed.

Labeling of anti-EGFR-MAb with the α-emitter 213Bi

The α-emitter 213Bi was eluted from a 225Ac/213Bi generator system provided by the Institute for Transuranium Elements.35 Elution of 213Bi as (213BiI4)−/(213BiI5)2− anions was accomplished with 600 μl of 0.1 M HCl/0.1 M NaI. Anti-EGFR-MAb (100 μg; matuzumab, Merck) conjugated with the 213Bi-chelating agent SCN-CHX-A“-DTPA 36 (Macrocyclics) was added in 0.4 M ammonium acetate buffer (pH 5.3) and incubated for 7 min at room temperature. 213Bi-labeling of the anti-EGFR-MAb is done via chelation of 213Bi3+ by CHX-A”-DTPA. Unbound 213Bi was removed via size-exclusion chromatography and purity of 213Bi-anti-EGFR immunoconjugates was checked as described.37

Fractionated radioimmunotherapy with 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb

Mice that had been intravesically instilled with 2 × 106 EJ28-luc cells were divided into 5 different groups: untreated control group (n = 10), native anti-EGFR-MAb group (n = 10), therapy group 1 (n = 20), therapy group 2 (n = 24), and histology group (n = 8). Animals of the native anti-EGFR-MAb group were treated 3 times intraperitoneally with 1 μg of anti-EGFR-MAb at the day of tumor detection and at days 4 and 8 thereafter. In therapy groups 1 and 2, animals were injected intraperitoneally (in 50 μl of PBS) with 0.46 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb at the day of tumor detection as well as at days 4 and 8 thereafter and with 0.93 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb at the day of tumor detection as well as 7 d thereafter, respectively. The efficacy of the different therapies was monitored via bioluminescence imaging and survival. From the histology group 6 mice were left untreated and one mouse each was treated 3 times with 0.46 MBq or 2 times with 0.93 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb as described above. At different time points after treatment, the bladders of the animals were analyzed via autoradiography, immunohistochemistry or histopathology in terms of tumor development and therapeutic efficacy.

The animals of the 3 toxicity groups (5 mice each) were treated with different activities of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb, however without prior instillation of EJ28-luc cells. In toxicity group 1, mice received 3 instillations of 0.46 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb at an interval of 4 days. In toxicity groups 2 and 3, mice received 2 instillations of 1.85 MBq and 3.7 MBq of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb at an interval of 7 days, respectively. Effects of the different activities of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb on tumor-free bladder urothelia were subsequently investigated histopathologically.

All mice were observed daily for signs of illness and were euthanized as soon as a large tumor burden, nephropathy, ascites or cachexia were detected.

Detection of EGFR via autoradiography of bladder sections

The μ-IMAGER™ (Raytest) is a high-resolution digital measuring device which detects radionuclide-labeled molecules in histopathological tissue sections. This device was used to locate EGFR molecules in the bladder urothelium via binding of 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb. For this purpose, paraffin sections of tumor-bearing bladders (10 μm) were incubated with 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb (37 kBq/30 min). The histological specimens were exposed to a phosphor screen for 60 min and analyzed with the μ-IMAGER™ (Aida Image Analyzer, Raytest).

Immunohistochemical detection of EGFR

To verify EGFR-overexpressing urothelial tumors derived from intraevsical instillation of EJ28-luc cells, immunohistochemical staining of EGFR was performed postmortem in cryosections of the bladder. Cryosections (4 μm) were blocked with 5% mouse serum in PBS-bovine serum albumin for 30 min and subsequently incubated with anti-EGFR-MAb (matuzumab,1:40) for 1 h at room temperature. After blocking of endogenous peroxidases with methanol/H2O/H2O2, sections were incubated with polyclonal rabbit anti-human IgG, conjugated with horseradish-peroxidase (DAKO, 1:80) for 30 min at room temperature. Finally the peroxidase substrate DAB was applied for 10 min. After counterstaining with H&E the dried samples were evaluated with a light microscope.

Statistical methods

Mice that survived beyond the observation period were denoted >300. Survival rates were calculated and displayed via the Kaplan-Meier method. Within group analyses across the different groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) followed by a Fisher's Least Significant Difference (LSD) post hoc test. Independent t-tests were used to define which groups differed significantly from each other. P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical calculations were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL USA) and SigmaPlot (Systat, Erkrath).

Funding

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SE 962/2-4, SE 962/3-1) and by the European Commission FP7 Collaborative Project TARCC HEALTH-F2-2007-201962.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Parkin DM. The global burden of urinary bladder cancer. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl 2008; 218:12-20; PMID:19054893; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/03008880802285032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin 2007; 57:43-66; PMID:17237035; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Letašiová S, Medve'ová A, Šovčíková A, Dušinská M, Volkovová K, Mosoiu C, Bartonová A. Bladder cancer, a review of the environmental risk factors. Environ Health 2012; 11 (Suppl 1): S11; PMID:Can't; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1476-069X-11-S1-S11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sexton WJ, Wiegand LR, Correa JJ, Politis C, Dickinson SI, Kang LC. Bladder cancer: a review of non-muscle invasive disease. Cancer Control 2010; 17:256-68; PMID:20861813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williamson SR, Montironi R, Lopez-Beltran A, MacLennan GT, Davidson DD, Cheng L. Diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of carcinoma in situ of the urinary bladder: the state of the art. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2010; 76:112-26; PMID:20097572; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zaak D, Hungerhuber E, Schneede P, Stepp H, Frimberger D, Corvin S, Schmeller N, Kriegmair M, Hofstetter A, Knuechel R. Role of 5-aminolevulinic acid in the detection of urothelial premalignant lesions. Cancer 2002; 95:1234-8; PMID:12216090; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/cncr.10821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bastacky S, Ibrahim S, Wilczynski SP, Murphy WM. The accuracy of urinary cytology in daily practice. Cancer 1999; 87:118-28; PMID:10385442; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990625)87:3%3c118::AID-CNCR4%3e3.0.CO;2-N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Rhijn BWG, Burger M, Lotan Y, Solsona E, Stief CG, Sylvester RJ, Witjes JA, Zlotta AR. Recurrence and progression of disease in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: From epidemiology to treatment strategy. Eur Urol 2009; 56:430-42; PMID:19576682; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sylvester RJ, Oosterlinck W, van der Meijden AP. A single immediate postoperative instillation of chemotherapy decreases the risk of recurrence in patients with stage Ta T1 bladder cancer: a meta-analysis of published results of randomized clinical trials. J Urol 2004; 171(Pt 1):2186-90; PMID:15126782; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/01.ju.0000125486.92260.b2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sio TT, Ko J, Gudena VK, Verma N, Chaudhary UB. Chemotherapeutic and targeted biological agents for metastatic bladder cancer: a comprehensive review. Int J Urol 2014; 21:630-7; PMID:24455982; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/iju.12407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbet J, Bardiès M, Bourgeois M, Chatal JF, Chérel M, Davodeau F, Faivre-Chauvet A, Gestin JF, Kraeber-Bodéré F. Radiolabeled antibodies for cancer imaging and therapy. Methods Mol Biol 2012; 907:681-97; PMID:22907380; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/978-1-61779-974-7_38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Navarro-Teulon I, Lozza C, Pèlegrin A, Vivès E, Pouget JP. General overview of radioimmunotherapy of solid tumors. Immunotherapy 2013; 5:467-87; PMID:23638743; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2217/imt.13.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jurcic JG. Radioimmunotherapy for hematopoietic cell transplantation. Immunotherapy 2013; 5:383-94; PMID:23557421; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2217/imt.13.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seidl C, Essler M. Radioimmunotherapy for peritoneal cancers. Immunotherapy 2013; 5:395-405; PMID:23557422; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2217/imt.13.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahle J, Abbas N, Bruland ØS, Larsen RH. Toxicity and relative biological effectiveness of alpha emitting radioimmunoconjugates. Curr Radiopharm 2011; 4:321-8; PMID:22202154; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2174/1874471011104040321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim YS, Brechbiel MW. An overview of targeted alpha therapy. Tumour Biol 2012; 33:573-90; PMID:22143940; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s13277-011-0286-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seidl C. Radioimmunotherapy with α-particle-emitting radionuclides. Immunotherapy 2014; 6:431-58; PMID:24815783; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2217/imt.14.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorin JB, Ménager J, Gouard S, Maurel C, Guilloux Y, Faivre-Chauvet A, Morgenstern A, Bruchertseifer F, Chérel M, Davodeau F, et al.. Antitumor immunity induced after α irradiation. Neoplasia 2014; 16:319-28; PMID:24862758; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neo.2014.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Røtterud R, Nesland JM, Berner A, Fossa SD. Expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor family in normal and malignant urothelium. BJU Int 2005; 95:1344-50; PMID:15892828; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05497.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pfost B, Seidl C, Autenrieth M, Saur D, Bruchertseifer F, Morgenstern A, Schwaiger M, Senekowitsch-Schmidtke R. Intravesical alpha-radioimmunotherapy with 213Bi-anti-EGFR-MAb defeats human bladder carcinoma in xenografted nude mice. J Nucl Med 2009; 50:1700-8; PMID:19793735; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2967/jnumed.109.065961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan E, Patel A, Heston W, Larchian W. Mouse orthotopic models for bladder cancer research. BJU Int 2009; 104:1286-91; PMID:19388981; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08577.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hadaschik BA, Black PC, Sea JC, Metwalli AR, Fazli L, Dinney CP, Gleave ME, So AI. A validated mouse model for orthotopic bladder cancer using transurethral tumour inoculation and bioluminescence imaging. BJU Int 2007; 100:1377-84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan ES, Patel AR, Smith AK, Klein JB, Thomas AA, Heston WD, Larchian WA. Optimizing orthotopic bladder tumor implantation in a syngeneic mouse model. J Urol 2009; 182:2926-31; PMID:19846165; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soloway MS, Masters S. Urothelial susceptibility to tumor cell implantation: influence of cauterization. Cancer 1980; 46:1158-63; PMID:7214299; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/1097-0142(19800901)46:5%3c1158::AID-CNCR2820460514%3e3.0.CO;2-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe T, Shinohara N, Sazawa A, Harabayashi T, Ogiso Y, Koyanagi T, Takiguchi M, Hashimoto A, Kuzumaki N, Yamashita M, et al.. An improved intravesical model using human bladder cancer cell lines to optimize gene and other therapies. Cancer Gene Ther 2000; 7:1575-80; PMID:11228536; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Günther JH, Jurczok A, Wulf T, Brandau S, Deinert I, Jocham D, Bohle A. Optimizing syngeneic orthotopic murine bladder cancer (MB49). Cancer Res 1999; 59:2834-7; PMID:10383142 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sato A, Klaunberg B, Tolwani R. In vivo bioluminescence imaging. Comp Med 2004; 54:631-4; PMID:15679260 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zinn KR, Chaudhuri TR, Szafran AA, O'Quinn D, Weaver C, Dugger K, Lamar D, Kesterson RA, Wang X, Frank SJ. Noninvasive bioluminescence imaging in small animals. ILAR J 2008; 49:103-15; PMID:18172337; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/ilar.49.1.103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jurczok A, Fornara P, Soling A. Bioluminescence imaging to monitor bladder cancer cell adhesion in vivo: a new approach to optimize a syngeneic, orthotopic, murine bladder cancer model. BJU Int 2008; 101:120-4; PMID:17888045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colquhoun AJ, Mellon JK. Epidermal growth factor receptor and bladder cancer. Postgrad Med J 2002; 78:584-9; PMID:12415079; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/pmj.78.924.584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verdoorn BP, Kessler ER, Flaig TW. Targeted therapy in advanced urothelial carcinoma. Oncology (Williston Park) 2013; 27:219-26; PMID:23687793 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong YN, Litwin S, Vaughn D, Cohen S, Plimack ER, Lee J, Song W, Dabrow M, Brody M, Tuttle H, et al.. Phase II trial of cetuximab with or without paclitaxel in patients with advanced urothelial tract carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30:3545-51; PMID:22927525; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.9572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morgenstern A, Bruchertseifer F, Apostolidis C. Targeted alpha therapy with 213Bi. Curr Radiopharm 2011; 4:295-305; PMID:22202152; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2174/1874471011104040295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buchhorn HM, Seidl C, Beck R, Saur D, Apostolidis C, Morgenstern A, Schwaiger M, Senekowitsch-Schmidtke R. Non-invasive visualisation of the development of peritoneal carcinomatosis and tumour regression after 213Bi-radioimmunotherapy using bioluminescence imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2007; 34:841-9; PMID:17206415; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00259-006-0311-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morgenstern A, Bruchertseifer F, Apostolidis C. Bismuth-213 and actinium-225 – generator performance and evolving therapeutic applications of two generator-derived alpha-emitting radioisotopes. Curr Radiopharm 2012; 5:221-7; PMID:22642390; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2174/1874471011205030221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mirzadeh S, Brechbiel MW, Atcher RW, Gansow OA. Radiometal labeling of immunoproteins: covalent linkage of 2-(4-isothiocyanatobenzyl)diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid ligands to immunoglobulin. Bioconjug Chem 1990; 1:59-65; PMID:2095205; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bc00001a007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seidl C, Schröck H, Seidenschwang S, Beck R, Schmid E, Abend M, Becker KF, Apostolidis C, Nikula TK, Kremmer E, et al.. Cell death triggered by alpha-emitting 213Bi-immunoconjugates in HSC45-M2 gastric cancer cells is different from apoptotic cell death. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2005; 32:274-85; PMID:15791436; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00259-004-1653-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]