Abstract

Endometriosis is a gynaecologic disease characterized by endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity. Commonly it affects the pelvic organs. When endometrial nodules or plaques are localized in sites other than the uterus or ovaries, it is termed extragenital endometriosis. Adequate pre-operative assessment is essential for treatment planning. MRI is a non-invasive method with high spatial resolution that allows the multiplanar evaluation of genital and extragenital endometriosis. Herein, we present a pictorial review of a variety of extragenital endometriosis cases, all of which can be encountered in clinical practice.

INTRODUCTION

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterine cavity, affecting as many as 10–20% of fertile females and up to 50% of infertile females.1 It occurs commonly in the genital organs (uterus, ovaries, vaginal fornix and the upper portion of the posterior cervix).

Its presence within the abdomen in sites other than in the genital organs is termed extragenital endometriosis, and it can be subdivided into pelvic or extrapelvic endometriosis. The mechanism responsible for the extragonadal endometriosis is unclear: it has been hypothesized that retrograde menstruations can lead to metastatic peritoneal implantations or the serosal cells may be stimulated towards a metaplastic differentiation. However, extraperitoneal localizations could be owing to vascular or lymphatic dissemination.

The most frequently involved extragenital pelvic structures by endometrial implants are the uterosacral ligaments (70%), vagina (14%), rectum (10%), rectovaginal septum or bladder (6%).2 Extrapelvic involvement is rare, but may be seen in sites such as the abdominal wall, navel, diaphragm and peripheral nerves; much more uncommon sites are the lungs or brain. The extragenital lesions are often sites of deep endometriosis, a specific condition characterized by lesions penetrating into the retroperitoneal space or the wall of the organs to a depth of at least 5 mm. The infiltrative lesions of deep endometriosis are mainly characterized by fibromuscular hyperplasia that surrounds the foci of endometriosis, which sometimes contain small cavities.3

Although a relatively common condition, endometriosis remains difficult to recognize, diagnose and treat because of its extremely variable presentation (dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, urinary tract symptoms and infertility), which is particularly true for rare extrapelvic endometriosis (pneumothorax and catamenial epistaxis). Furthermore, the lifetime risk of ovarian cancer is increased from 0.3 to 1 in 100 in females with endometriosis, with higher risk in females with ovarian endometriosis.4 So far, laparoscopy remains the gold standard for the diagnosis and staging of endometriosis; but, diagnostic pitfalls with this technique include the failure to identify atypical lesions lacking the characteristic brown or black appearance as well as those obscured by dense adhesions and subperitoneal disease.5,6

Nowadays, an imaging examination is routinely performed and it plays an indispensable role in the accurate staging of the endometriosis. Sonography is the first imaging technique, but it is useless for extrapelvic implants and the limitation of ultrasound lies in its reduced sensitivity for endometrial plaques.3 MRI has a pivotal role in the evaluation of genital and extragenital endometriosis for obtaining an adequate pre-operative planning. It shows high accuracy in the diagnosis and prediction of disease extent. Firstly, MRI is extremely useful in the detection of deeply infiltrating endometrial implants, even in the setting of diffuse adhesions that may result in complete obliteration of the posterior cul-de-sac.7 Secondly, its wider field of view compared with ultrasound permits the identification of lesions far from the genital organs, as in the case of intraspinal endometriosis. Moreover, MRI could help in the differentiation of deep pelvic endometriosis from inflammatory conditions or neoplastic lesions of the pelvic organs.

MRI PROTOCOL TECHNIQUE

It is well known that neither the severity of the pain nor the location of the pain correlates with the location of endometriosis and the amount of disease. Therefore, a rigorous technique is mandatory to avoid underdiagnoisis or misdiagnosis. At our institution, examinations are scheduled in the first 12 days after the beginning of the menstrual cycle. During this phase of the menstrual cycle, the hyperintense signal of endometriotic blood is maximal in the T1 weighted images and the small haemorrhagic foci can be detected. Furthermore, the signal intensity of blood is crucial for the differentiation of the endometrioma from other ovarian lesions, like simple or haemorrhagic cysts; the endometrioma is characteristically hyperintense on T1 weighted images and hypointense in the T2 weighted images (T2 shading effect).

The bladder should be moderately filled in order to precisely assess its walls and the space between the bladder and uterus. The standard MRI protocol on a 1.5-T imager includes high-resolution turbo spin-echo T2 sequences acquired in three orthogonal planes, axial and sagittal fat-saturated spin-echo T1 sequences, axial spin-echo T1 and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) sequences. No intravenous contrast medium is routinely used: if requested, 15 s after the intravenous injection of the gadolinium contrast medium, the acquisition of axial and sagittal or coronal fat-saturated T1 weighted sequences is performed. For spin-echo sequences, the matrix size is 512 × 512 and the field of view (FOV) is settled as small as possible. Slice thickness is 4 mm, with a distant factor of 20%. DWI is performed using a single-shot echoplanar imaging (EPI) sequence with a matrix of 192 × 192, section thickness/gap of 4/0 mm and b-values of 50, 400 and 900 mm2; the quantitative assessment is performed on the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map generated from the DWI images with different b-values.

Fat-saturated T1 weighted sequences are most sensitive for the detection of bloody foci and allows differentiation between the haemorrhagic or fatty content of cystic lesions (Figure 1). The high-resolution T2 weighted sequences show in detail organ margins and fat planes (Figure 2). Thus, with these sequences, the distortion of the structures is accurately assessed, a finding often correlated to the presence of fibrotic and retracting lesions, adhesions or ligament thickening (Figure 3). The T1 weighted sequence is useful for a correct definition of the signal of normal structures (like muscles, fat and bone) and it is essential for the characterization of lesions of the uterus and ovaries.

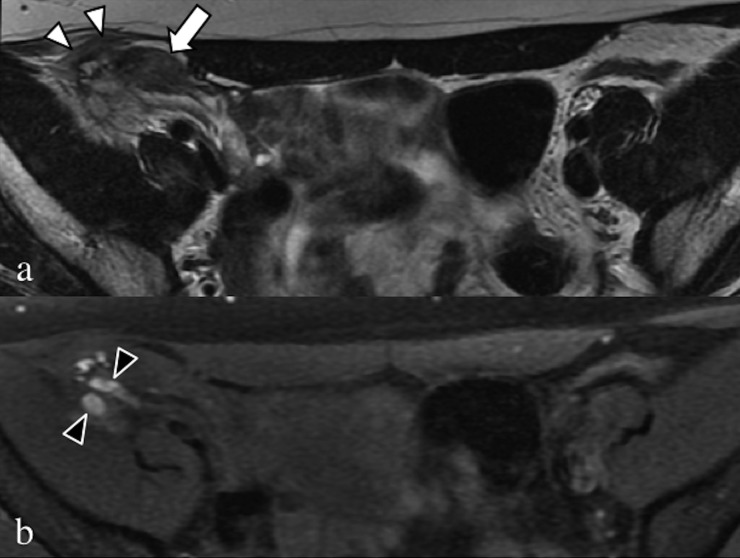

Figure 1.

Axial T2 weighted (a) and fat-saturated T1 weighted (b) images. Large fibrotic and haemorrhagic endometrial localization (arrow) in the middle and lateral portion of the right round ligament infiltrating the oblique muscle and the T1 weighted sequence (black arrowheads).

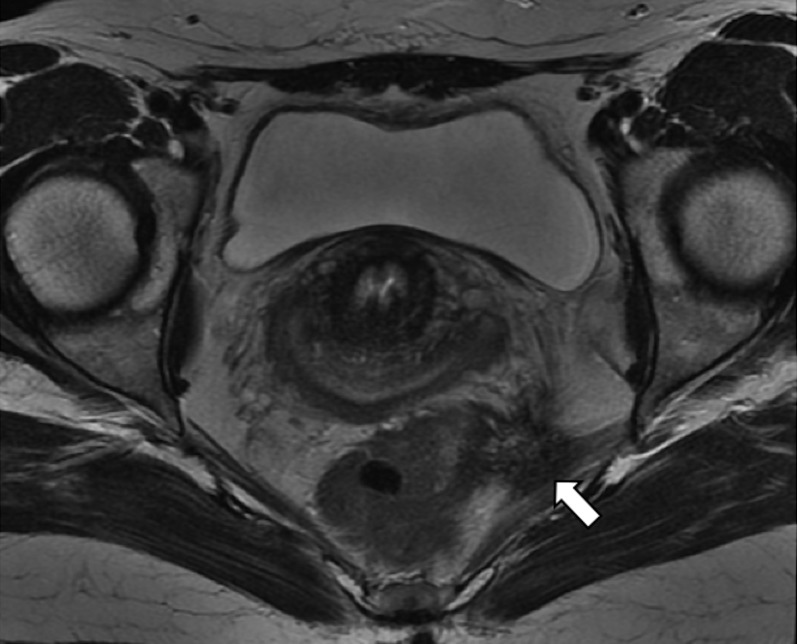

Figure 2.

Axial T2 weighted image. Retracting endometrial lesion (arrows) of the left uterosacral ligament, with involvement of the piriformis muscle and the lateral wall of the rectus.

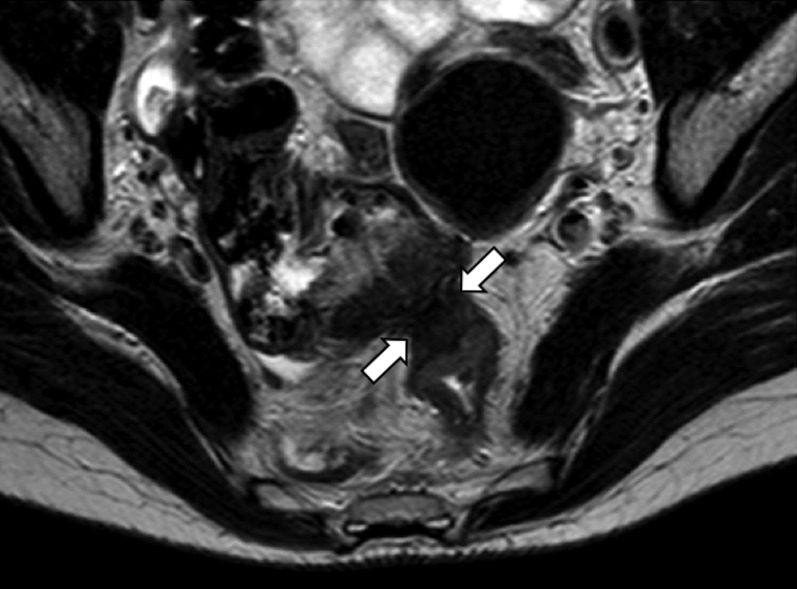

Figure 3.

Axial T2 weighted image. Hypointense endometrial lesion (arrows), with invasion and retraction of the anterior wall of the left colon and of the caecum wall, which is dislocated in the Douglas' pouch. The fat plane is obscured.

The presence of a low ADC value within an adnexal lesion is not specific: haemorrhagic ovarian cysts, endometriomas, solid endometrial implants, mature cystic teratomas and malignancies can all show a restricted diffusion (Figure 4). However, deep endometriosis implants show a consistently low ADC value too, regardless of their location within the abdomen, and this sign could improve the specificity for the detection of extragonadal lesions. The degree of enhancement after gadolinium contrast media of deep pelvic endometriosis depends mostly on the inflammatory status of the tissues. Contrast-enhanced imaging is primarily required to assess solid enhancing nodules, when a malignant transformation (especially of ovarian masses) or an inflammatory process is suspected (Figure 5).

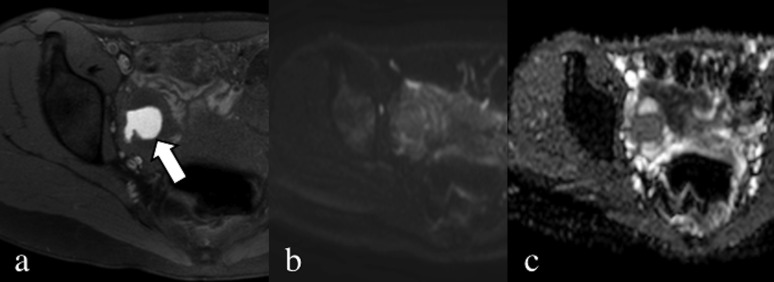

Figure 4.

Axial fat-saturated T1 weighted image without contrast (a), diffusion-weighted image (b = 900) (b) and apparent diffusion coefficient map (c). Endometrial lesion of the right ovary characterized by the presence of blood (arrow); the mass has no specific slightly restricted diffusion water movement.

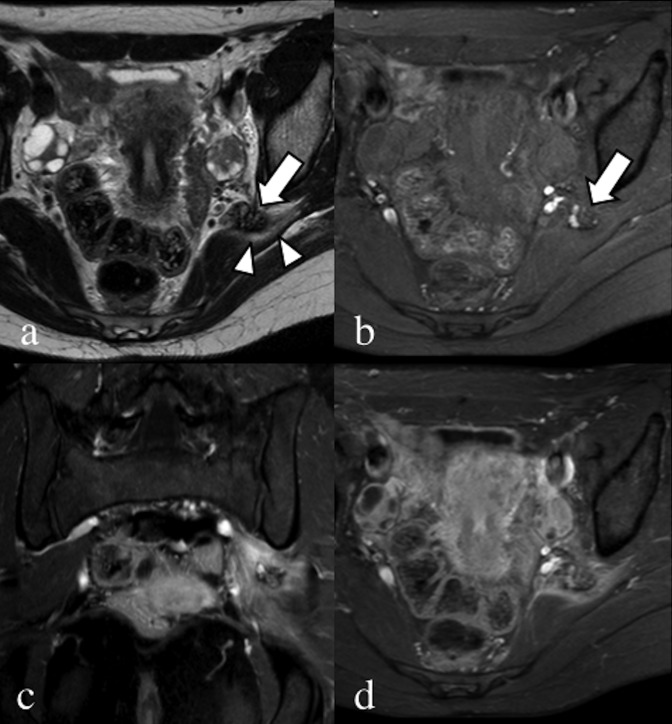

Figure 5.

Axial T2 weighted (a) and fat-saturated pre-contrast T1 weighted (b) images. Coronal (c) and axial (d) fat-saturated T1 weighted images after the injection of gadolinium contrast media. A 28-year-old patient, with catamenial sciatic pain. Endometrial nodular lesion of the left sciatic nerve (arrows), characterized by hypointense signal with hyperintense foci on the T2 weighted image. Notice the oedema of the piriformis muscle (arrowheads). After contrast injection, there is enhancement of the piriformis muscle due to inflammation, clearly seen in the coronal image compared with the contralateral.

MRI FINDINGS

Extragenital endometriosis at MRI shows as solid masses or soft-tissue thickening, with low-to-intermediate signal in both T2 and T1 weighted images (like most fibrotic lesions); the margins are usually irregular or stellate. Small superficial implants can be found on the serosa of any abdominal organ and they lack the infiltrative behaviour typical of deep endometriosis foci. Furthermore, this sign may be confirmed by punctate regions of high signal intensity on fat-saturated T1 weighted images (Figures 6, 7). The clinical meaning of finding haemorrhagic foci is not clear yet: the presence of blood is owing to the activity of endometrial glands and so these lesions could theoretically better respond to the hormonal drugs, (decreasing the proliferation of endometriotic stromal cells), compared with the lesions formed mainly by fibromuscular hyperplasia. The effectiveness of this therapy has been demonstrated for endometriomas,8 but further evaluation for deep endometriosis nodules is needed.

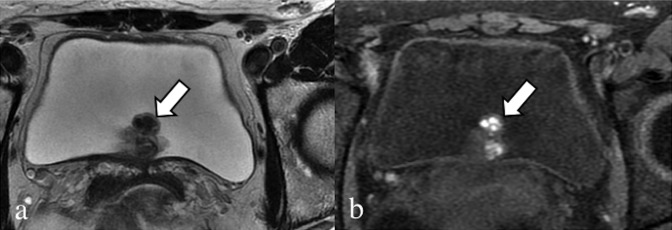

Figure 6.

Axial T2 weighted (a) and fat-saturated T1 (b) weighted images. Exophytic endometrial lesion (arrows) of the posterior bladder wall, showing lobulated margins, low signal in T2 weighted image and very high signal blood foci in the T1 weighted image sequence.

Figure 7.

Coronal fat-saturated T1 weighted image (a), sagittal (b) and coronal (c) T2 weighted images. Fibrotic and haemorrhagic endometrial nodule (arrows) in the abdominal wall affecting both rectus muscles, arising from the scar of the previous C-section.

The most common localizations of extragenital endometriosis are uterosacral ligaments. On MRI, when a focus of endometriosis is present, the ligaments are thickened or are involved by a stellate solid mass with hypointense T2 signal. Another frequent site of deep endometriosis is the rectovaginal septum: an irregular hypointense solid mass fills this space between the walls of the organs, retracting them. Similarly, the space between the bladder and uterus can be occupied by a hypointense mass that protrudes in the bladder wall.

Complications of extragenital endometriosis

Indirect signs can suggest the presence of deep endometrial lesions, owing to their marked infiltrative behaviour. It is crucial to look out for these signs, because these are frequently the main findings and can lead to a prompt diagnosis of a pelvic or extrapelvic localization of endometriosis. The symptoms of endometriosis can be subtle, and endometriosis is one of the major causes of chronic pelvic pain. For example, adhesions are the most common complications of extraovarian endometriosis. They may be identified as spiculated low-signal-intensity strands that obscure fat spaces and organ interfaces (Figure 8).1Usually, these strands depart from a solid mass and present low signal on T2 weighted images. Additional findings in the presence of adhesions are posterior displacement of the uterus and ovaries, angulation of the bowel loops, elevation of the posterior vaginal fornix and a hydrosalpinx /haematosalpinx. The involvement of these structures may cause chronic pelvic pain, infertility or constipation. Therefore, pelvic endometriosis is sometimes misdiagnosed for years, in favour of more frequent pathologies of the genital or gastrointestinal apparatus. The involvement of the ureteral wall can lead to urinary tract obstruction, with subsequent hydroureter or hydronephrosis (Figure 9); in these cases, abdominal pain and haematuria might be the presenting complaints (Figure 10).

Figure 8.

Axial (a) and coronal (b) T2 weighted images. Small bowel endometrial lesion (arrows), with hypointense signal. The lesion grows in the lumen of the bowel with partial obstruction. In the coronal view, the hypointense vertical lines (arrowheads) represent retracting fibrotic strands.

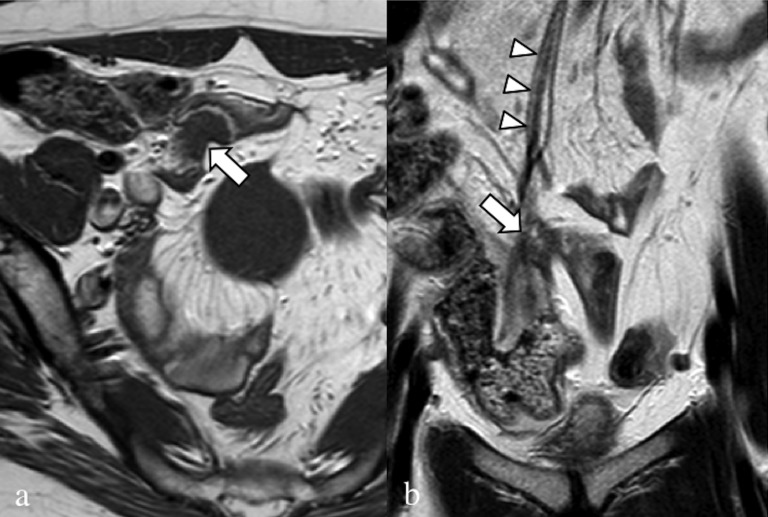

Figure 9.

Axial (a) and sagittal (b) T2 weighted images. Retracting endometrial lesion (arrows), located in the lower portion of the right obturator region, anteriorly to the piriformis muscle. The nodule has a stellate shape with undefined margins, and the right ureter (u) is obstructed with consequent hydroureteronephrosis.

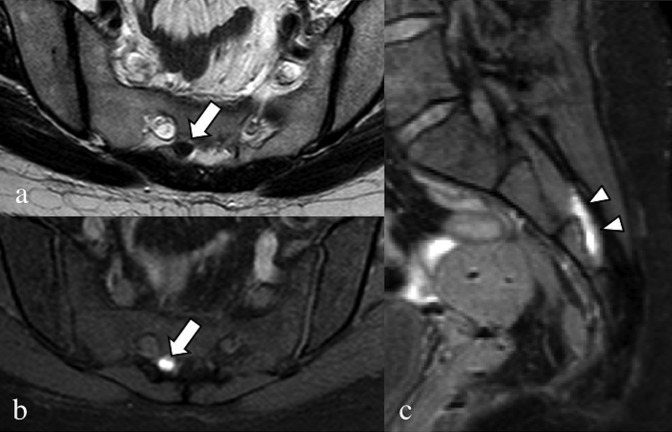

Figure 10.

Axial fat-saturated T1 weighted image (a), axial (b) and sagittal (c) T2 weighted images. 45-year-old patient, operated for severe pelvic endometriosis (hysterectomy). Solid round-shaped lesion of the bladder neck-first segment of the urethra (arrows), showing high signal in the T1 weighted sequence and intermediate signal in the T2 weighted sequences.

Deep rectosigmoid nodules can show a “mushroom cap”’ appearance in the T2 weighted sequences, as an umbrella-like head of a mushroom growing into the lumen owing to the hypertrophy of the muscularis propria as well as fibrotic adhesion and convergence of the serosa, often misinterpreted as rectosigmoid colon cancer, Crohn's disease or other submucosal tumours (Figure 11).9 In our experience, in this particular case, the injection of gadolinium contrast media could be helpful, because the sigmoid localizations of endometriosis usually show low-grade enhancement, but an endoscopic biopsy is recommended.

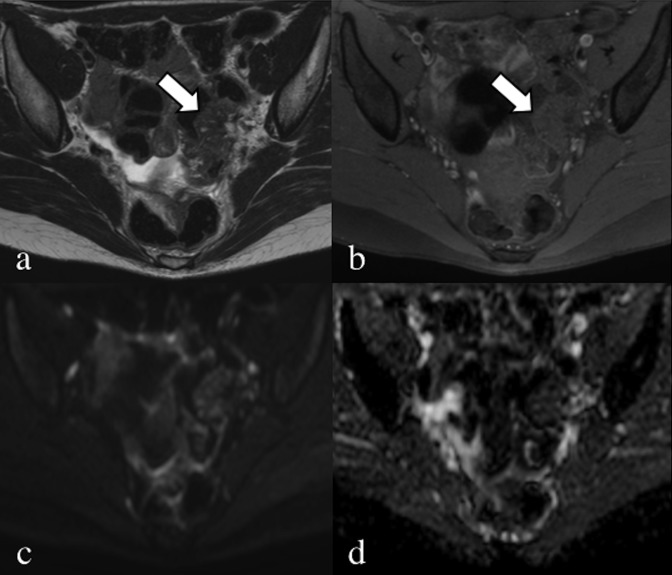

Figure 11.

Axial T2 weighted (a) and fat-saturated T1 weighted images (b). A 33-year-old patient, with pelvic pain and catamenial haematochezia. Typical “mushroom cup” appearance (arrows) of a stenotic endometrial lesion of the sigma; the wall is irregularly thickened with hypointense signal and some hyperintense foci in the T2 weighted image. Diffusion-weighted image (b = 900) (c) and apparent diffusion coefficient map (d) showing a slightly restricted movement of water, not specific but consistent with an endometrial lesion as proved after surgery.

Uncommon extrapelvic locations, like nerves, liver, diaphragm (Figure 12), navel (Figure 13) and lymph nodes (Figure 14), show signal and morphologic characteristics similar to those of the pelvic endometrial nodules; e.g. nerve involvement is suspected when there is an asymmetric thickening and alteration of the normal low signal (Figure 15). The lumbosacral plexus is the most commonly involved nervous structure and can produce non-specific sciatic, obturator or femoral nerve symptoms.

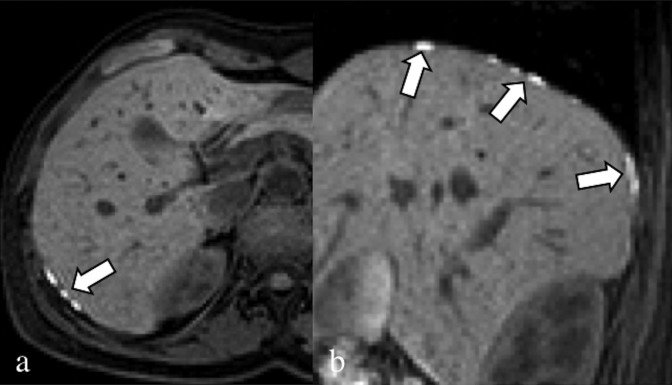

Figure 12.

Axial (a) and sagittal (b) fat-saturated T1 weighted image. 30-year-old patient complaining about dysmenorrhoea and upper abdominal pain, which travelled to the right shoulder. Multiple endometrial lesions of the diaphragm (arrows); the nodules are characterized by a hyperintense signal in the fat-saturated T1 weighted sequences owing to the presence of blood.

Figure 13.

Sagittal T2 weighted (a) and fat-saturated T1 weighted (b) images. A 29-year-old patient, with catamenial bleeding from the navel. Haemorrhagic endometrial lesion located at the navel (arrows). In the anterior wall of the uterus, there is a round-shaped hypointense subserosal fibroid.

Figure 14.

Coronal T2 weighted image. A 35-year-old patient with chronic pelvic pain. Severe endometrial lesions of the ovaries. The MRI scan showed unspecific multiple lobulated lymph nodes >15 mm (arrows): based on the presence of endometriomas, an additional endometrial localization was supposed, but malignancies could not be excluded. After surgical removal, the lymph nodes proved positive for endometriosis.

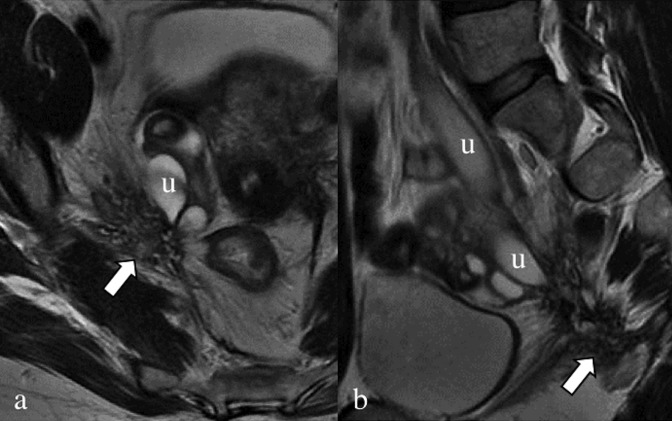

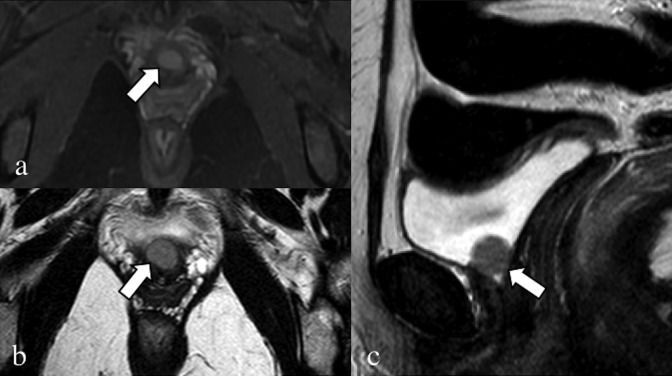

Figure 15.

Axial T2 weighted image (a), axial (b) and sagittal (c) fat-saturated T1 weighted images. A 32-year-old patient, operated on numerous times for severe pelvic endometriosis (hysterectomy); the patient complained about right catamenial claudication. In (a) and (b), the intracanal root of the right nerve S3 (arrows) is enlarged, with hypointense signal in the T2 weighted sequence and very high signal in the T1 weighted sequence. Even the extracanal portion of S3 (arrowheads) is enlarged with very high signal.

SUMMARY

Radiologists have to be aware of the various clinical and imaging presentations of endometriosis when evaluating a patient with pelvic pain or infertility or when characterizing an adnexal mass. Atypical presentations and locations of endometriosis often create a greater diagnostic challenge but should be considered in the assessment of childbearing females with recurrent/chronic or cycle-related pain. MRI is a reliable technique to assess the extension of endometrial disease, providing key information for the diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Nevertheless, histology remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of extrapelvic endometriosis, characterized by the presence of endometrial glandular tissues.

Contributor Information

Katiuscia Menni, Email: katiuscia.menni@aochiari.it.

Luca Facchetti, Email: facchettil@gmail.com.

Paolo Cabassa, Email: paolocab@libero.it.

REFERENCES

- 1.Woodward PJ, Sohaey R, Mezzetti TP, Jr. Endometriosis: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 2001; 21: 193–216; questionnaire 288–94. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.1.g01ja14193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Del Frate C, Girometti R, Pittino M, Del Frate G, Bazzocchi M, Zuiani C. Deep retroperitoneal pelvic endometriosis: MR imaging appearance with laparoscopic correlation. Radiographics 2006; 26: 1705–18. doi: 10.1148/rg.266065048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coutinho A, Jr, Bittencourt LK, Pires CE, Junqueira F, Lima CM, Coutinho E, et al. MR imaging in deep pelvic endometriosis: a pictorial essay. Radiographics 2011; 31: 549–67. doi: 10.1148/rg.312105144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melin A, Sparén P, Persson I, Bergqvist A. Endometriosis and the risk of cancer with special emphasis on ovarian cancer. Hum Reprod 2006; 21: 1237–42. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kataoka ML, Togashi K, Yamaoka T, Koyama T, Ueda H, Kobayashi H, et al. Posterior cul-de-sac obliteration associated with endometriosis: MR imaging evaluation. Radiology 2005; 234: 815–23. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2343031366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choudhary S, Fasih N, Papadatos D, Surabhi VR. Unusual imaging appearances of endometriosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009; 192: 1632–44. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bazot M, Darai E, Hourani R, Thomassin I, Cortez A, Uzan S, et al. Deep pelvic endometriosis: MR imaging for diagnosis and prediction of extension of disease. Radiology 2004; 232: 379–89. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2322030762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyashita M, Koga K, Takamura M, Izumi G, Nagai M, Harada M, et al. Dienogest reduces proliferation, aromatase expression and angiogenesis, and increases apoptosis in human endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol 2014; 30: 644–8. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2014.911279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoon JH, Choi D, Jang KT, Kim CK, Kim H, Lee SJ, et al. Deep rectosigmoid endometriosis: “mushroom cap” sign on T2-weighted MR imaging. Abdom Imaging 2010; 35: 726–31. doi: 10.1007/s00261-010-9643-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]