Abstract

The development of the single cell layer skin or hypodermis of Caenorhabditis elegans is an excellent model for understanding cell fate specification and differentiation. Early in C. elegans embryogenesis, six rows of hypodermal cells adopt dorsal, lateral or ventral fates that go on to display distinct behaviors during larval life. Several transcription factors are known that function in specifying these major hypodermal cell fates, but our knowledge of the specification of these cell types is sparse, particularly in the case of the ventral hypodermal cells, which become Vulval Precursor Cells and form the vulval opening in response to extracellular signals. Previously, the gene pvl-4 was identified in a screen for mutants with defects in vulval development. We found by whole genome sequencing that pvl-4 is the Paired-box gene pax-3, which encodes the sole PAX-3 transcription factor homolog in C. elegans. pax-3 mutants show embryonic and larval lethality, and body morphology abnormalities indicative of hypodermal cell defects. We report that pax-3 is expressed in ventral P cells and their descendants during embryogenesis and early larval stages, and that in pax-3 reduction-of-function animals the ventral P cells undergo a cell fate transformation and express several markers of the lateral seam cell fate. Furthermore, forced expression of pax-3 in the lateral hypodermal cells causes them to lose expression of seam cell markers. We propose that pax-3 functions in the ventral hypodermal cells to prevent these cells from adopting the lateral seam cell fate. pax-3 represents the first gene required for specification solely of the ventral hypodermal fate in C. elegans providing insights into cell type diversification.

Keywords: C. elegans, fate specification, differentiation, gene expression, PAX, epidermis

Introduction

A major event in metazoan development is the separation of the epidermal layer from the ectoderm and the surrounding of the developing embryo by an epidermal epithelium. As development proceeds, epidermal precursors will become specified into different cell types that perform varied functions. In the nematode C. elegans, the epidermis is a single cell layer thick and is referred to as a hypodermis or hypodermal layer (for review, see (Chisholm and Hardin 2005; Hall and Altun 2008; Chisholm and Hsiao 2012; Chisholm and Xu 2012)). The majority of the C. elegans embryonic hypodermal cells are derived from the AB blastomere and are born after 240 minutes of embryogenesis. Most of the embryonic hypodermal precursors are initially present as a group of dorsal cells organized into six rows which will go on to surround the developing embryo by epiboly (Figure S1A). These six rows of embryonic cells can be divided into three main hypodermal cell types found at hatching: most cells of the inner two rows will interdigitate and fuse together to form the syncytial dorsal hypodermis Hyp 7 that eventually surrounds much of the animal; many of the cells in the outer two rows will become ventral hypodermal cells called P cells, while cells of the two middle rows will become the lateral hypodermal cells or seam cells located between the dorsal and ventral cell types (other minor hypodermal cells participate in formation of the head and tail hypodermis) (Figure S1B).

During larval development, the lateral and ventral hypodermal cells divide to generate over 100 cells that join the syncytial hypodermis surrounding the animal (hyp 7) as well as making other cells that form specialized epidermal structures (Sulston and Horvitz 1977; Hall and Altun 2008). The lateral hypodermal seam cells are present on the left and right sides of the newly hatched larva as a single row of cells extending from the nose to tail. Most seam cells divide once during each of the four larval stages in an asymmetric stem cell-like division to generate a daughter that joins the syncytial hypodermis and a daughter that retains the seam cell fate and the ability to divide further (Figure S1D (reviewed in (Hall and Altun 2008; Joshi et al. 2010))). After the fourth larval stage, all of the seam cells terminally differentiate and fuse together to form a single lateral cell that secretes a specialized structure called alae. Conversely, at hatching a subset of the ventral hypodermal cells, called P cells, are found as two rows of six cells arranged on either side of the ventral midline (Figure S1C; reviewed in (Greenwald 1997; Sternberg 2005)). During the L1 stage the anterior daughters of seam cells send cellular protrusions between the P cells that separates the P cell pairs, which then rotate 90° to make a single row of 12 P cells (P1-P12) along the anterior-posterior axis. Toward the end of the L1 larval stage, the 12 P cells divide to produce anterior daughters that are neuroblasts (Pn.a cells) and posterior daughters that are hypodermoblasts (Pn.p cells) (Figure S1D). In hermaphrodites, six of these cells (P1.p, P2.p, P9.p-P11.p, P12.pa) fuse with the hyp 7 syncytium in the L1. The remaining cells, P3.p-P8.p, do not fuse and constitute the Vulval Precursor Cells (VPCs); these cells are induced by extracellular signaling to form the vulva, which connects the uterus to the outside.

Several factors involved in the specification of these early hypodermal cell fates have been identified; however in comparison to our knowledge of other early embryonic cell types such as the germ line, endoderm or mesoderm, much less is known (Figure S2; see (Chisholm and Hsiao 2012)). Expression of two genes, elt-1 and lin-26, is believed to confer a general hypodermal fate on cells. elt-1 encodes a GATA-family transcription factor and is considered a ‘master regulator’ of the hypodermal cell fate; elt-1 is expressed early in all hypodermal precursors and is necessary and sufficient for proper hypodermal cell fate specification (Spieth et al. 1991; Page et al. 1997; Gilleard and McGhee 2001). The gene lin-26 is a downstream target of ELT-1 that encodes a zinc-finger transcription factor. lin-26 is also expressed in all hypodermal cells but is believed to function in the maintenance of epidermal cell fates, rather than cell fate specification (Labouesse et al. 1994; Labouesse et al. 1996). Finally, the nuclear hormone receptor gene nhr-25 also functions downstream of elt-1 and appears to play a role in early hypodermal fate specification, as well as functioning in other aspects of hypodermal function (Gissendanner and Sluder 2000; Chen et al. 2004; Silhankova et al. 2005).

A number of transcription factor encoding genes are known to function in the specification of the three main embryonic hypodermal cell types. Adoption of the dorsal hypodermal fate is dependent on the function of the redundant T-box genes tbx-8 and tbx-9; when function of both genes is compromised, severe defects in morphogenesis of the dorsal hypodermis result (Andachi 2004; Pocock et al. 2004). The lateral hypodermal (seam) cell fate is regulated by the ceh-16 gene, which encodes an engrailed homolog (Cassata et al. 2005), and the adjacent genes egl-18 and elt-6, which encode functionally redundant GATA factors (Koh and Rothman 2001). Expression of egl-18 is dependent on ceh-16, so is likely to be a direct or indirect target (Cassata et al. 2005). Mutation of either ceh-16 or egl-18 results in misspecification of the lateral hypodermal (seam) cells; the lateral cells fuse with the syncytial hypodermis, perhaps indicating adoption of a dorsal hypodermal fate (Koh and Rothman 2001; Cassata et al. 2005). elt-3 is another GATA factor encoding gene that acts downstream of elt-1 and is expressed early in development; however elt-3 is expressed in only the non-lateral hypodermal cells (dorsal and ventral) (Gilleard et al. 1999). Unlike elt-1, elt-3 is not necessary to specify epidermal fates, as elt-3 mutants show normal development of the skin, however it is sufficient to drive adoption of epidermal cell fates in the absence of elt-1 (Gilleard and McGhee 2001). The repression of elt-3 in the lateral hypodermal cells requires the activity of egl-18, although whether this is a direct repression or a consequence of egl-18 mutants adopting an alternative fate is unclear (Koh and Rothman 2001). Finally, little is known about the initial specification of the ventral hypodermal cell type (P cell fate); beyond the general hypodermal factors elt-1 and lin-26, there are no genes currently known that are required to specify this hypodermal fate (Figure S2; (Chisholm and Hsiao 2012)).

We report here on the further characterization of a mutation, pvl-4(ga96), originally identified in a screen for mutants with defects in development of the vulva, a ventral hypodermal derivative arising from P cell progeny (Eisenmann and Kim 2000). ga96 mutants were previously found to have too few Pn.p nuclei in the ventral midline, resulting in vulval defects. We now find that ga96 is a missense mutation in the gene pax-3, which encodes the only C. elegans member of the PAX3/7 Paired-box transcription factor family of vertebrates (Hobert and Ruvkun 1999). We demonstrate that pax-3 is expressed in the P cells in the embryo, and the P cells and their progeny (Pn.a and Pn.p cells) in early larvae. Consistent with this expression, pax-3 reduction-of-function (rof) leads to defects in the P cells, the mothers of the Pn.p cells. At hatching the ventral P cells display defects in expression of the junctional marker ajm-1::gfp, display an abnormal shape, and make abnormal inter-P cell contacts that are associated with defects in body morphology. Further analysis showed that in pax-3(rof) animals, the P cells in the L1 and their lineal descendants in later larval stages misexpress three markers of the lateral hypodermal (seam) cell fate, including the seam cell specification gene egl-18. Ectopic expression of pax-3 in the seam cells themselves inhibited the expression of seam markers in those cells. Together these results suggest that the function of pax-3 is to inhibit expression of the lateral hypodermal fate in cells that will adopt the ventral hypodermal fate. Thus, we have identified the first factor that appears to be required for adoption of the ventral hypodermal fate, and the first factor involved in distinguishing the ventral hypodermal (P cell) and lateral hypodermal (seam cell) fates from one another.

Materials and Methods

C. elegans strains and alleles

C. elegans genetic methods were performed as previously described (Brenner 1974). N2 Bristol was used as the wild-type strain. Experiments were performed at 20°C unless indicated otherwise. The following alleles used in this work are described in Wormbase (Harris et al. 2010; Yook et al. 2012):

LGII dpy-10(e128), pvl-5(ga87), eff-1(hy21), rol-6(e187), pvl-4(ga96), bli-1(e768), unc-52(e444), mnDf29/mnC1

LGIII unc-119(e2498), pha-1(e2123)

LGIV ced-3(n717)

LGV him-5(e1490).

The following integrated transgenic arrays were used:

jcIs1 [ajm-1::gfp; unc-29(+); rol-6(su2006d)] from strain SU93 (Köppen et al. 2001)

wIs51 [scm::gfp; unc-119(+)] from strain JR667 (Koh and Rothman 2001)

wdIs4 [unc-4p::gfp; dpy-20(+)] from strain NC197 (Pflugrad et al. 1997)

sIs12963 [grd-10p::gfp; dpy-5(+)] from strain BC13248 (McKay et al. 2003)

stIs10645 [pax-3p::his-24::mCherry; unc-119(+)] from strain RW10645 (Pingault et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2009)

arIs99 [dpy-7::yfp] from strain GS3798 (Myers and Greenwald 2005)

Identification of pvl-4(ga96)

Traditional three factor mapping placed pvl-4(ga96) on chromosome II between unc-4 and rol-1 (~ 5.2 map unit interval) (Eisenmann and Kim 2000). To further localize pvl-4(ga96), SNP mapping was done as described (Wicks et al. 2001). Briefly, CB4856 males were mated with rol-6(e187) pvl-4(ga96) bli-1(e769) hermaphrodites. F2 Bli non-Rol and Rol non-Bli recombinants were cloned and their Egl or vulval phenotype was noted. A 500–900 bp region around each SNP was amplified from homozygous F3 recombinant lysates and either sequenced or cut with a restriction enzyme (for polymorphisms that changed a restriction site) to determine which polymorphisms associated with pvl-4(ga96) (Williams et al. 1992). Analysis of the SNP data from F2 recombinants placed pvl-4 in a region spanning seven cosmids (F52H3, C18D1, ZK945, F27E5, F33H1, R05H5, and T01E8) between +1.84 and +2.17 on LG II (data not shown).

To identify the pvl-4(ga96) mutation the genomes of pvl-4(ga96) and a contemporaneous mutant strain, pvl-5(ga87) (Joshi and Eisenmann 2004), were sequenced and compared in the region to which pvl-4 was mapped. Genomic DNA (gDNA) libraries were constructed according to the manufacturer’s protocols (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Briefly, one microgram of gDNA was sheared by sonication, end-repaired, A-tailed, adapter-ligated, size-fractionated by gel electrophoresis, and PCR-amplified. Short-read (76-cycle) sequencing of the pvl-4(ga96)-bearing and pvl-5(ga87) comparison strain yielded 43.9 and 48.5 × 10e6 high-quality reads, respectively, for 33.4 and 36.9-fold genome coverage. Reads were aligned to the C. elegans reference genome WS190 with BFAST (Homer et al. 2009). Sequence variants were called using SAMTools (Li et al. 2009). Non-synonymous mutations were identified using ANNOVAR (Wang et al. 2010). Sequence variants in the mutant strain were filtered against those present in the comparison strain to generate a list of unique candidates. The missense mutation affecting a conserved amino acid of PAX-3 was pursued as a likely candidate for the mutation causing the pvl-4 mutant phenotype.

pax-3 rescuing translational GFP reporter

Splicing by Overlap Extension (SOEing) PCR was used to construct the pax-3 rescuing translational reporter (pax-3p::pax-3::gfp) (Hobert 2002). pax-3p::pax-3::gfp consists of the pax-3 promoter (2655 bp upstream of ATG) fused to the open reading frame of pax-3 (5595 bp) with a C-terminal gfp fusion followed by the unc-54 3′ UTR. The pax-3 promoter, coding sequence, and downstream region were amplified from N2 genomic DNA; gfp::unc-54 3′ UTR was amplified from plasmid pPD95.75 (gift of Andy Fire). Transgenic rescue of pvl-4(ga96) phenotypes was performed by microinjecting the pax-3p::pax-3::gfp PCR product (100ng/μl) and the co-injection marker ajm-1::gfp (100ng/μl) into pvl-4(ga96);him-5(e1490) hermaphrodites (Mello and Fire 1995). Because of the extrachromosomal nature of the Ex[pax-3p::pax-3::gfp; ajm-1::gfp] arrays we were able to score for rescue of pvl-4(ga96) phenotypes based on whether or not worms were expressing the ajm-1::gfp co-injection marker. To score for rescue of embryonic lethality, 30 green hermaphrodites were picked to a seeded plate and allowed to lay eggs for 6 hours. The hermaphrodites were removed and after two hours, green and non-green embryos were picked to a fresh plate. The next day, the number of unhatched (dead) embryos was counted. For the other phenotypes (Vab, vulval induction, and Pn.p cell number) animals were scored for the phenotype and only then examined for the presence of GFP expression in the vulval region.

We noted that although the rescuing translation reporter (pax-3p::pax-3::gfp) and the pax-3 transcriptional reporter (pax-3p::mCherry) contain approximately the same size promoter fragment (2655 bp upstream of the ATG for the former, 2616 bp upstream for the latter), the translational reporter did not show robust gfp expression in P cells in the embryo and early larval stages as seen with pax-3p::mCherry. This difference could be due to the slightly smaller upstream region, the presence of intronic control elements, the different 3′ UTR or the intrinsic stability of the PAX-3::GFP fusion protein. A second independent transcriptional reporter was also created, pax-3p::gfp. pax-3p::gfp consists of the pax-3 promoter (2655 bp upstream of ATG) driving expression of gfp sequences, followed by 624 bp downstream of the pax-3 stop codon. This reporter showed the same embryonic expression pattern as pax-3p::mCherry (K. Thompson and D. Eisenmann, unpublished observations).

Ectopic expression of pax-3

A full-length pax-3 cDNA was amplified from an N2 cDNA library and cloned into plasmid pPD49.78 (heat shock promoter vector was a gift of Andy Fire) via a KpnI site, creating plasmid pKT102. To create strain pha-1(e2123); grd-10::gfp; hsp::pax-3, pKT102 (50 ng/ul) and pha-1(+) (50 ng/ul) DNA were injected into grd-10p::gfp; pha-1(e2123) worms; two independent lines were obtained and maintained at 25°C as extrachromosomal arrays. We refer to this array as hsp::pax-3. For heat-shock analysis, synchronized populations of hsp::pax-3 worms were shifted for 30 minutes to 37 °C as embryos (mixed stage) or at the L1/L2, L2/L3, and L3/L4 larval molts, and allowed to develop to the mid-L4 larval stage. At this time, the number of grd-10::gfp expressing seam cell nuclei were counted and compared to non-heat-shocked controls.

To create grd-10p::pax-3, SOEing PCR was used to fuse the grd-10 promoter (782 bp upstream of ATG) to the pax-3 cDNA sequence and unc-54 3′ UTR. N2 genomic DNA was used as template to amplify the grd-10 promoter and pKT102 was used as template to amplify pax-3::unc-54 3′ UTR. The grd-10p::pax-3::unc-54 3′ UTR (50 ng/ul) PCR product was microinjected into grd-10p::gfp; pha-1(e2123) worms with pha-1(+) (50 ng/ul) DNA and lines were maintained at 25°C until scoring.

RNA interference (RNAi)

Feeding RNAi was performed as previously described (Kamath et al. 2001). RNAi constructs were obtained from the Ahringer RNAi-feeding library (Kamath and Ahringer 2003). Embryos were added to RNAi-feeding plates and allowed to grow to young adults, which were transferred to fresh RNAi-feeding plates and their progeny were scored. For RNAi by injection of dsRNA, a 259 bp fragment of the pax-3 locus was amplified by PCR from N2 genomic DNA and cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega). Both forward and reverse constructs were linearized using NsiI, RNA was made using Ambion’s MEGAscript High Yield Transcription Kit, purified using Ambion’s MEGAclear kit and forward and reverse transcripts were annealed by heating and cooling to room temperature. Double-stranded pax-3 RNA was injected into the gonad of sIs12963 young adult hermaphrodites at a concentration of 1μg/μl and progeny scored as described above.

Observation of P cells, Pn.p cells, and seam cells

Synchronized L1 stage pax-3(ga96) animals were obtained by allowing embryos to hatch on NGM plates with no food overnight. The following day the newly hatched L1 larvae were added to NGM plates with OP50 and allowed to feed until they reached the mid-L2 larval stage when Pn.p nuclei were observed and counted using Nomarski DIC optics on a Zeiss Axioplan2 microscope. To observe and count P cells and seam cells in pax-3(ga96); jcIs1 animals, L1 stage worms were obtained as described above and scored using fluorescent microscopy on a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope. To observe P cells in pax-3(RNAi) animals containing the ajm-1::gfp hypodermal junctional marker we placed starved L1 larvae on pax-3 RNAi-feeding plates and allowed animals to produce progeny. The progeny were allowed to develop to gravid adults and their embryos were isolated by standard bleach methods. These embryos were added to M9 buffer and allowed to hatch overnight. The next day, P cells were scored for the Gap and Dis phenotypes (described below). sIs12963 animals injected with pax-3 dsRNA were observed by picking progeny of injected animals and viewed using the Axioplan2 fluorescent microscope.

Data availability

Strains, plasmids and sequences of oligonucleotide used are available upon request.

Results

Phenotypic analysis of pvl-4(ga96)

To identify novel genes regulating C. elegans vulval development, we previously carried out a forward genetic screen for animals displaying a protruding vulva phenotype and identified a single allele of a novel gene named pvl-4(ga96) (Eisenmann and Kim 2000). This hypomorphic mutation was found to cause defects in embryonic development, larval body morphology and vulval development. To understand the role of this gene in hypodermal and vulval development, we sought to further characterize the pvl-4 mutant phenotypes and determined the gene altered by the ga96 mutation.

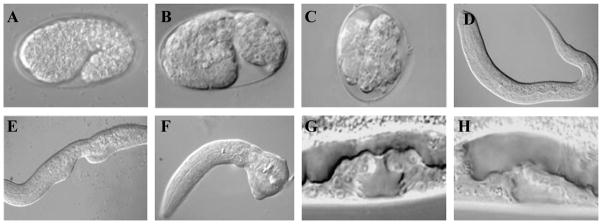

We found that 27% of ga96 animals die as embryos, some with a very disorganized body morphology (Table 1, Figure 1A – C). Almost half of the animals that do hatch display body morphology defects (Vab, Table 1) that range from subtle (Figure 1D) to severe (Figure 1E, F); 15% of newly hatched larvae fail to survive. Hermaphrodites that survived larval life had several adult phenotypes indicative of defects in vulval development, including protruding vulva (Pvl), egg-laying defective (Egl) and gonad eversion through the vulva (Spew) (Table 1). We also found that ga96 adult hermaphrodites have gonad migration defects in which one or both arms of the developing gonad fail to turn correctly (Table 1) and that 33% (n=40) of ga96 adult males have abnormal ray morphology in the male tail (data not shown).

Table 1.

pvl-4(ga96) and pax-3(RNAi) phenotypes

| strain | Emb | Vab | Spew | Gonad mig. | Pvl | Egl | Vulval induction | Pn.p nuclei |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 1% (300) | 0% (50) | 0% (100) | 2% (50) | 0% (100) | 0% (100) | 3.0 (50) | 11.0 (100) |

| pvl-4(ga96) | 27%** (381) | 48%** (114) | 20%** (317) | 12%* (56) | 27%** (317) | 38%** (317) | 2.4 (56) | 7.6 +/− 1.3 (90) |

| pvl-4(ga96) 25° C | 58%** (310) | 63%** (56) | 18%** (100) | 30%** (67) | 25%** (100) | 52%** (100) | 1.9 (66) | 5.5 +/− 1.7# (75) |

| RNAi control | 2% (308) | 0% (50) | 0% (100) | 0% (50) | 0% (100) | 0% (100) | 3.0 (50) | nd |

| pax-3(RNAi) | 35%** (293) | 48%** (50) | 11%** (90) | 16%* (50) | 36%** (90) | 72%** (90) | 2.0 (50) | nd |

Strains scored at 20°C unless noted otherwise. Emb, embryonic lethality; Vab, variable abnormal body morphology; Spew, everted gonad; GM, gonad migration defect; Pvl, protruding vulva; Egl, egg-laying defective. ‘Vulval induction’ indicates average number of vulval precursor cells (P5.p - P7.p) adapting induced fates per animal. ‘Pn.p nuclei’ indicates average number of Pn.p nuclei ± standard deviation in the ventral cord at the L2 larval stage (P12.p was not scored). The Pvl, Egl, and Spew data at 20°C are from Eisenmann and Kim, 2000.

P<0.05 and

P<0.001 compared with appropriate control animals.

t test, P<0.0001 compared to pvl-4(ga96) animals grown at 20°C.

Figure 1.

Nomarski photomicrographs of wild-type and pvl-4(ga96) animals at different stages of development. (A) Wild-type 1.5 fold stage embryo. (B, C) pvl-4(ga96) embryos with disorganized morphology. (D) Wild-type early L1 stage larvae. (E) pvl-4(ga96) L1 larvae with Vab body morphology phenotype. (F) pvl-4(ga96) L1 larvae lacking posterior structures. (G) Wild-type L4 stage larvae with properly induced vulval structure (three Pn.p cells adopted induced fates). (H) pvl-4(ga96) L4 animal showing Underinduced vulval phenotype.

The vulval-related phenotypes seen in ga96 animals were previously attributed to a decrease in the number of ventral hypodermal cells (Pn.p cells) in these animals: wild type animals have 11 large Pn.p nuclei at the L2 stage (P1.p - P11.p; excluding P12.p), while ga96 animals have an average of 7.6 (Table 1 and (Eisenmann and Kim 2000)). Since three of the Pn.p cells (P5.p - P7.p) divide to generate the vulval opening, this reduction in Pn.p cell nuclei leads to an Underinduced vulval phenotype in which fewer than three vulval precursor cells (VPCs) adopt vulval fates (Figure 1G, H and Table 1).

The Pn.p cells are the posterior daughters of the P cells, which are born in the embryo and divide in the early L1 stage to generate anterior neuroblast daughters (Pn.a cells) and posterior hypodermal daughters (Pn.p cells) (Figure S1D). The Pn.a neuroblasts divide several times and contribute 56 neurons to the ventral nerve cord, which contains a total of 71 neurons by the L2 stage (Sulston and Horvitz 1977). To determine if ga96 animals also have defects in Pn.a cells, we counted ventral cord neurons. While wild type animals had an average of 69 ventral cord nuclei with neuronal morphology, ga96 animals had only 54 (Table 2). One class of the Pn.a-derived neurons expresses the homeodomain containing transcription factor UNC-4 (Miller and Niemeyer 1995); ga96 mutants also had fewer unc-4p::gfp expressing neurons than wild type animals (Table 2). The fact that there were fewer Pn.a derivatives in the ventral cord in pax-3(ga96) argues against cell fate transformation of Pn.p cells to a Pn.a fate as a reason for the decrease in Pn.p cell numbers. Instead, the fact that ga96 animals had a deficit in both Pn.p cells and Pn.a-derived cells suggested that these animals likely had an earlier defect in the P cells, the mothers of the Pn.a and Pn.p cells.

Table 2.

pvl-4(ga96) mutants have a reduced number of Pn.a-derived neurons

| unc-4p::gfp | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Strain | Pn.a nuclei ± SD | n | expressing neurons ± SD | n |

| N2 | 69.2 ± 1.7 | 35 | 19.0 ± 2.8 | 50 |

| pvl-4(ga96) | 54.0 ± 8.1* | 35 | 15.0 ± 2.7* | 50 |

Individual Pn.a nuclei in L2-stage animals were counted by Nomarski microscopy. unc-4p::gfp expressing neurons in L2 stage animals were counted by epifluorescent microscopy. SD - standard deviation.

t test, p<0.0001 compared to N2 control.

Eisenmann and Kim showed that almost all ga96/deficiency animals failed to hatch, indicating that the null phenotype of pvl-4 may be embryonic lethality and that the ga96 mutation is likely hypomorphic (Eisenmann and Kim 2000). Consistent with a reduction-of-function, we found that the ga96 mutation is temperature-sensitive: most of the phenotypes we observed had an increased penetrance at 25° compared to 20° (Table 1).

The pvl-4(ga96) allele is a missense mutation in the Paired-box gene, pax-3

We used a combination of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) mapping and whole genome sequencing to determine the molecular identity of the ga96 allele (see Materials and Methods). Previous work using three-factor crosses placed pvl-4 between unc-4 and rol-1 on LG II (Eisenmann and Kim 2000). Using SNP mapping between N2 ga96 and Hawaiian strains of C. elegans we were able to further narrow down the ga96 locus to a 0.3 cM region covered by seven cosmids (between F52H3 and T01E08 (Table S1; data not shown). Whole genome sequencing was performed on pvl-4(ga96) and on a strain from the same genetic screen carrying a different mutation on LGII (pvl-5(ga87) (Joshi and Eisenmann 2004)) and the seven cosmid region was compared between these contemporaneous mutant strains to identify molecular lesions. A single SNP was identified in an exon of the Paired-box gene, pax-3 (F27E5.2) (Hobert and Ruvkun 1999). The SNP is a C to T change (consistent with EMS mutagenesis) generating a missense mutation that causes a Pro29Leu change (CCC to CTC) in a residue conserved in most PAX homologs (Xu et al. 1995; Hobert and Ruvkun 1999). This same Pro to Leu mutation has also been identified in humans suffering from Waardenburg syndrome, a developmental disease linked to mutations in the human PAX3 gene (P50L in humans (Pingault et al. 2010)).

Two previous results supported the hypothesis that pvl-4 is the pax-3 gene. First, genome-wide RNA interference studies indicated that RNAi against the pax-3 gene causes a protruding vulva phenotype (Kamath and Ahringer 2003; Simmer et al. 2003). Second, the pax-3 gene has been shown to be involved in vulva formation in the related nematode species Pristionchus pacificus (Yi and Sommer 2007). To verify that pvl-4 is pax-3 we performed pax-3 RNAi in a wild-type background. Compared to RNAi controls, pax-3 RNAi causes several phenotypes that overlap with pvl-4(ga96) mutants including embryonic lethality, Vab body morphology, and vulval and gonad migration defects (Table 1). Additionally, we introduced a pax-3p::pax-3::gfp transgene into pvl-4(ga96) animals along with an ajm-1::gfp co-injection marker. The pax-3p::pax-3::gfp transgene rescued the Pn.p cell deficit, head and body morphology abnormalities, underinduced L4 vulva phenotype, and embryonic lethality phenotypes in ga96 mutant animals carrying the transgene (Table 3 and Figure 2). In particular, animals harboring the pax-3(+) rescuing array were almost completely rescued for the missing Pn.p cell phenotype: GFP(+) animals had an average of 10.9 Pn.p nuclei at the L2-stage compared to an average of 8 Pn.p nuclei in GFP(−) animals. Based on the above findings we concluded that pvl-4 is pax-3 and we will refer to the gene as pax-3.

Table 3.

A pax-3 transgene rescues pvl-4(ga96) phenotypes.

| Strain genotype | % Emb | n | % Vab | n | % wild-type vulval induction | n | # of Pn.p nuclei | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 1 | 300 | 0 | 50 | 100 | 50 | 11 | 100 |

| pvl-4(ga96); him-5(e1490); Ex[pax-3p::pax-3::gfp; ajm-1::gfp] GFP(−) | 47 | 320 | 82 | 28 | 19 | 46 | 8.0 ± 2.5 | 27 |

| pvl-4(ga96); him-5(e1490); Ex[pax-3p::pax-3::gfp; ajm-1::gfp] GFP(+) | 8* | 364 | 21* | 33 | 94* | 51 | 10.9 ± 0.3** | 20 |

Columns show penetrance of each phenotype and number of animals scored. The Vab phenotype was scored at the L1 stage. Vulval induction was scored at the L4 stage. Pn.p nuclei were counted at the L2 stage. Embryonic lethality represents green GFP(+) (with extrachromosomal array) or non-green GFP(−) (without extrachromosomal array) embryos that failed to hatch.

P<0.0001 compared to non-green (GFP−) animals.

t test, P<0.0001 compared to non-green (GFP−) animals.

Figure 2. Transgenic rescue of pvl-4(ga96) phenotypes.

pvl-4(ga96) animals were microinjected with a combination of pax-3p::pax-3::gfp (rescue) and ajm-1::gfp (marker) DNA. The extrachromosomal nature of the pax-3p::pax-3::gfp; ajm-1::gfp array allowed us to compare animals containing the array (marked by ajm-1::gfp expression in the pharynx and vulva) to animals not containing the array and subsequently score for rescue of pvl-4(ga96) phenotypes. (A–D) Nomarski images of L1 stage (A, B) and L4 stage (C, D) larvae. Animals containing the pax-3p::pax-3::gfp; ajm-1::gfp extrachromosomal array (green) were rescued for the Vab body morphology defect (B) and Underinduced vulval phenotype (D). Animals lacking the extrachromosomal array (non-green) showed these phenotypes (A, C). Note that the green color shows AJM-1::GFP at cell junctions in the pharynx (B) and developing vulva (D); PAX-3::GFP expression is too faint to see in these animals. Anterior is to the right and ventral towards the top in all images.

pax-3 is expressed in a subset of AB-derived hypodermal cells during embryogenesis and their descendants during larval development

Previous work using an automated analysis of a pax-3 transcriptional reporter showed that pax-3 is expressed in AB-derived cells during embryogenesis and in the head, neurons and blast cells in L1 stage animals (Liu et al. 2009; Murray et al. 2012). In agreement with this work, using the same transcriptional reporter strain (pax-3p::mCherry) we first observed pax-3 reporter expression around 240 minutes post first cleavage in AB-derived cells. Specifically, on the left side of the embryo expression was seen in (anterior to posterior) hyp4, hyp6, two hyp 7 cells, P1/2L, P3/4L, seam cell V3L, P5/6L, P7/8L, P9/10L, and four cells clustered at the posterior end of the embryo (TL, hyp 7, PVQL, PHBL) (Murray et al. 2012) (Figure 3A – D; the same pattern was observed on the right). pax-3 reporter expression continued in many of these cells to the end of embryogenesis (Figure 3E – H). In agreement with Liu et al., in the newly hatched L1 larva pax-3 reporter expression was seen in eight of twelve P cells (P1/2, P5/6, P7/8, P9/10) (Figure 3I and J) (Liu et al. 2009). Interestingly pax-3 reporter expression in P cell pairs P3/4 begins to fade in the embryo and is absent in the L1 stage, and expression was never observed in P cell pair P11/12 (Figure 3H, J and data not shown). pax-3 reporter expression continued in the Pn.a and Pn.p descendants of these P cells in the L2 stage (Figure 3K), but disappeared in the P cell descendants by the beginning of the L3 stage (data not shown). Using the rescuing pax-3p::pax-3::gfp reporter, we also observed evidence of pax-3 expression in the VulF cells of the L4 stage developing vulva (Figure 3L and M), in the migrating sex myoblasts (SM) and their descendants (data not shown), and in the developing male tail (data not shown). In summary, pax-3 expression was seen throughout embryogenesis and early larval development predominantly in hypodermal cells, in particular the ventral P hypodermal cells. This is the same ventral hypodermal lineage that displays defects in larval life in pax-3(rof) animals, suggesting a cell autonomous function for pax-3 in these cells.

Figure 3. Embryonic and early larval expression of pax-3.

(A–C) Nomarski (A), epifluorescent (B) and overlay (C) of embryo approximately 240 minutes post first cleavage expressing the pax-3p::mCherry reporter. (D) Schematic depicting the location of mCherry positive cells. Red cells indicate cells with mCherry expression in nuclei of labelled cells. Empty circles represent cells without pax-3 expression. Hypodermal cells are abbreviated with an h (e.g. h7 is hyp7). The P cells are labeled by brackets and numbered in pairs. The four symmetric pairs of cells in the posterior of the embryo are numbered as follows: (1) PVQ (2) PHB (3) T (4) hyp7. Red cells with a question mark were not identified. Note that pax-3p::mCherry reporter expression turns on in P cell pairs P1/2 and P9/10 just prior to the comma stage of embryogenesis. (E–H) Late comma stage embryo expressing the pax-3p::mCherry reporter and hypodermal cell junctional marker, ajm-1::gfp. AB-derived cells are labelled in H. (I) Ventral view of wild-type early L1-stage animal expressing ajm-1::gfp to mark hypdermal junctional boundaries. P cells are labeled 1–12 and are located between two rows of lateral seam cells (labelled V2-V6). (J) Early L1-stage animal expressing both ajm-1::gfp and pax-3p::mCherry reporters. At this stage the nuclei of the P cells have not migrated ventrally and are located near to the row of seam cells. (K) Late L1-stage animal with ajm-1::gfp, scm::gfp (marker of seam cell nuclei) and pax-3p::mCherry reporters. The a and p indicate anterior and posterior daughters of the indicated P cells, respectively. J and K are slightly ventro-lateral views, tilted left. The cells without mCherry expression in (J) and (K) are cells that do not express pax-3 reporters at this time (P3, P4, P11, P12) (L) Nomarski and (M) epifluorescence view of L4 stage vulva of animal carrying pax-3p::pax-3::gfp reporter, showing expression in VulF cells. Anterior is to the left.

pax-3 reduction-of-function results in the loss of hypodermal junctions and abnormal, disorganized P cells

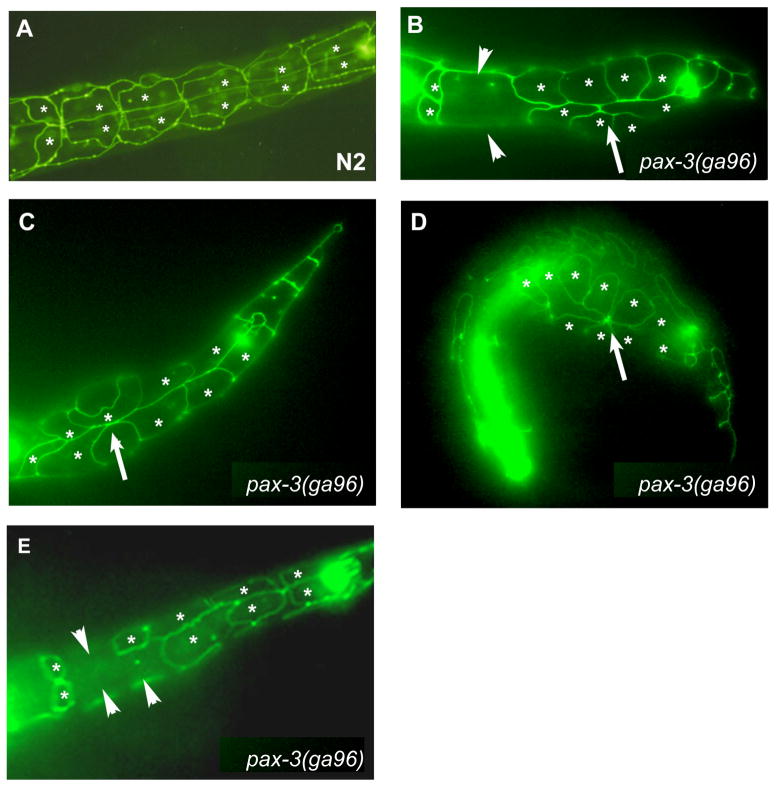

pax-3(ga96) mutants have deficits in both Pn.p and Pn.a-derived cells as larva, suggesting a defect in P cells in these mutant animals. To better understand this defect, we examined P cell morphology in pax-3(ga96) animals expressing ajm-1::gfp, a translational fusion protein that marks the junctions of all hypodermal cells (Köppen et al. 2001). In newly hatched L1 larvae, the 12 ajm-1::gfp expressing P cells are present as two rows of six cells in close apposition across the ventral midline; dorsally the P cells contact the row of lateral hypodermal seam cells (Figure 4A).

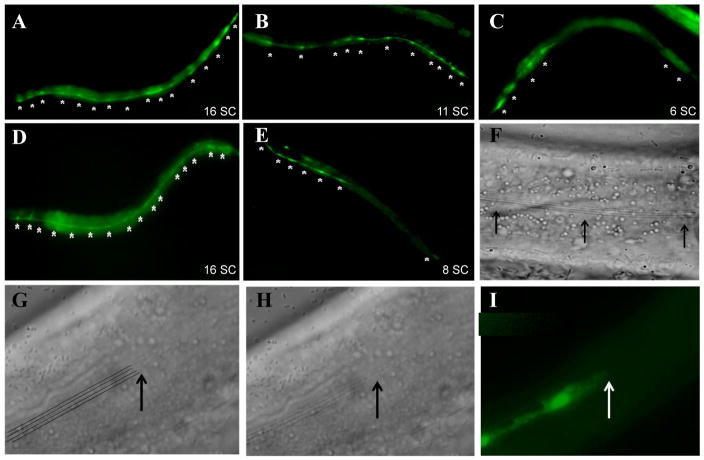

Figure 4. pax-3 reduction-of-function causes P cell phenotypes.

Epifluorescent images of L1-stage animals expressing the ajm-1::gfp hypodermal junctional marker. P cells are indicated with asterisks. (A) Wild-type L1 stage animal with six P cells pairs at the ventral midline. The seam cells are seen adjacent to P cells in a more dorsolateral position. (B – E) pax-3(ga96) L1-stage animals with P cells displaying either the Gap phenotype (loss of ajm-1::GFP expression between P cells: arrowheads) or the Disorganized phenotype (P cells making ectopic, inappropriate contacts with other P cells: arrows). All images are ventral views with anterior to the left.

We observed two phenotypes in pax-3(ga96) reduction-of-function L1 larvae. First, we saw the loss of ajm-1::gfp expression between some P cells (Figure 4B, E). This phenotype, which we refer to as the “Gap” phenotype, is observed in at least 80% of newly hatched pax-3(rof) larvae (Table 4). At 25°, the average pax-3(ga96) animal had only 4.2 (n = 50) P cell pairs in the ventral midline with correct ajm-1::gfp junctions, compared to six P cell pairs in wild type (Table 4). We believe that cells must still be present in the location of the P cells displaying a gap in ajm-1::gfp expression, since we did not observe herniation of the intervening tissues at these sites. All P cells exhibited the Gap phenotype, but P cells P1/2 and P3/4 had the lowest and highest penetrance, respectively (Figure 5A). Curiously, the cells with the highest Gap phenotype penetrance (P3/4, P11/12) were those that showed lowest pax-3 reporter expression in the L1 (Figure 3H, 3J).

Table 4.

P cell phenotypes in pax-3(rof) animals

| strain | penetrance % | # P cells affected | Range | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gap phenotype | ||||

| Wild type | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 |

| pax-3(ga96) ajm-1::gfp 20° | 88 | 3.2 | 0–8 | 50 |

| pax-3(ga96) ajm-1::gfp 25° | 98 | 3.6 | 0–8 | 50 |

| pax-3(RNAi) ajm-1::gfp; scm::gfp 20° | 80 | 3.8 | 0–10 | 45 |

| pax-3(RNAi) pax-3(ga96) ajm-1::gfp 20° | 97 | 5.6 | 0–10 | 35 |

| Dis phenotype | ||||

| Wild type | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 |

| pax-3(RNAi) pax-3(ga96) ajm-1::gfp 20° | 62 | 0.9 | 0–3 | 34 |

The shape and presence of junctions between P cells in newly hatched L1 larvae of the indicated strains were observed via the expression of the ajm-1::gfp reporter. Column 2 indicates the percent of animals showing the phenotype. Column 3 indicates the average number of P cells per animal with missing junctions (Gap phenotype) or the average number of disorganized P cells observed per animal (Dis phenotype). For the Gap phenotype, the lack of visible GFP expression between two P cells is taken as a missing junction in both cells. Column 4 indicates the range of the data in Column 3. Column 5 shows the number of animals observed.

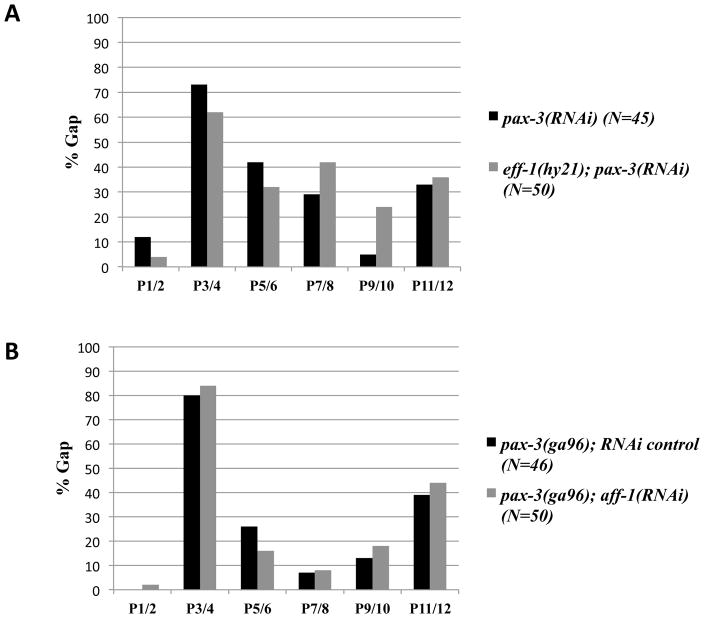

Figure 5. pax-3 reduction-of-function causes P cell phenotypes.

Prior to P cell pair separation and rotation it is not possible to distinguish individual P cells within pairs and the 12 P cells are grouped into six pairs (P1/2, P3/4, P5/6, P7/8, P9/10, and P11/12). All animals scored for the Gap or Dis phenotype (A, B) contained the ajm-1::gfp transgene. (A) Percentage of P cell pairs with Gap phenotype. (B) Percentage of P cell pairs with at least one cell displaying the Dis phenotype. (C) Percentage of P cell pairs in which at least one cell showed ectopic expression of scm::GFP in the P cells.

The second P cell phenotype we observed is that in many pax-3(rof) animals P cells were did not have the typical rectangular shape of an early L1 P cell, and the P cell array appeared disorganized with some P cells making ectopic contacts with other P cells they would not normally touch; we refer to this as the Disorganized (Dis) phenotype (Figure 4B–D). 62% of pax-3(rof) newly hatched L1 animals displayed at least one P cell pair with a Dis phenotype (Table 4); all P cells exhibited the Dis phenotype, with the phenotype most penetrant in P5/6, P7/8, and P9/10 (Figure 5B). We examined if there was a correlation between the body morphology defects observed in pax-3(ga96) animals and the Gap and Dis phenotypes. We found that 90% (29/32) of animals with a Gap, non-Dis phenotype had subtle or no body morphology defects, however pax-3(ga96) animals with both Dis and Gap phenotypes had body morphology defects, often near a P cell displaying a Dis phenotype. This suggests that the body morphology defects in pax-3(ga96) animals at the L1 stage may be due to P cells displaying a Dis phenotype.

Taken together, these data demonstrated that the ventral hypodermal P cells expressed pax-3 in the embryo and at hatching, and that in pax-3(rof) mutants the P cells exhibited defects in their shape, cell contacts and expression of the hypodermal marker ajm-1. If the affected P cells failed to survive, migrate or divide properly as in wild type, this could explain the reduced number of hypodermal Pn.p cells and Pn.a-derived neurons observed in pax-3(rof) animals.

pax-3 reduction-of-function does not cause inappropriate cell death or cell fusion

Previous work showed that pax family members egl-38 and pax-2 promote cell survival in C. elegans by regulating key components of the cell death machinery (Park et al. 2006). In addition, the pvl-5(ga87) mutant identified in the same Pvl screen as pax-3(ga96) was shown to have too few Pn.p cells, and this defect was suppressed by mutations in the cell death machinery (Joshi and Eisenmann 2004). To determine whether the P cells might be undergoing inappropriate cell death in pax-3 mutants as they do in pvl-5 mutants, we reduced the function of ced-3, which encodes a key caspase required for programmed cell death (Yuan and Horvitz 1990; Yuan et al. 1993). We found that the Pn.p cell number defect in L2-stage ga96 animals was not suppressed by loss of ced-3 function in either pax-3(ga96); ced-3(n717) or pax-3(ga96); ced-3(RNAi) animals, suggesting that inappropriate cell death was not the cause of reduced P cell numbers (Table S2).

All three major hypodermal cell types (hyp, seam and P cells) undergo homotypic cell fusion events to form syncytia that form the outer epithelial layer of the worm (Hall and Altun 2008). Inappropriate cell fusion between adjacent P cells would explain the absence of ajm-1::GFP expression between some P cells seen in pax-3(ga96) animals (Gap phenotype). In C. elegans, two fusogenic proteins have been identified. EFF-1 is required for almost all hypodermal cell fusion events, while AFF-1 acts in specific fusion events, including the fusion of the anchor cell to the uterine seam cells, the fusion of the vulval VulA and VulD rings, and the terminal fusion of the seam cells (Mohler et al. 2002; Sapir et al. 2007). To determine if there are inappropriate P cell fusions in pax-3(ga96) animals, we reduced the function of either eff-1 or aff-1 expression and looked for suppression of the Gap phenotype. We found that the Gap phenotype was not strongly suppressed in either pax-3(RNAi) eff-1(hy21) animals or pax-3(ga96) aff-1(RNAi) animals (Figure 6). These data suggested that the loss of ajm-1::GFP expression seen in pax-3(ga96) animals (Gap phenotype) is unlikely to be due to improper or premature P cell fusion events.

Figure 6. Reduction-of-function of the fusogen genes eff-1 and aff-1 function does not suppress the Gap P cell phenotype in pax-3 reduction-of-function animals.

In A and B, L1-stage animals expressing ajm-1::gfp were scored for the percent occurrence of P cell pairs with cellular junction surrounding all four sides of P cells. (A) The Gap phenotype caused by pax-3 RNAi is not suppressed in an eff-1(hy21) mutant background. (B) aff-1 reduction-of-function by RNAi does not suppress pax-3(ga96) Gap P cell phenotype.

pax-3 reduction-of-function causes a defect in P cell fate specification

The defects observed in some P cells in pax-3(rof) animals (loss of ajm-1::gfp expression, abnormal morphology and cell contacts, reduced number of descendants) could be due to a defect in fate specification of the P cells. To test if pax-3(rof) causes fate transformation of P cells to a more general hypodermal fate change, we performed pax-3 RNAi on a strain containing a dpy-7::yfp reporter. dpy-7::yfp is expressed in all hyp 7 cells, and turns on when Pn.p cells and their descendants fuse with the syncytial hypodermal cell hyp 7 (Gilleard et al. 1997; Myers and Greenwald 2005). We found that dpy-7::yfp L1-stage larvae treated with pax-3 RNAi had an average of 32.5 ± 2.1 hypodermal cells expressing GFP compared to 31.7 ± 2.3 cells in control animals (p = 0.09; data not shown). This difference was not statistically significant and did not account for the missing Pn.p cells in pax-3(rof) animals. Thus, the P cells do not appear to inappropriately adopt a syncytial hypodermal cell fate in pax-3 reduction-of-function animals.

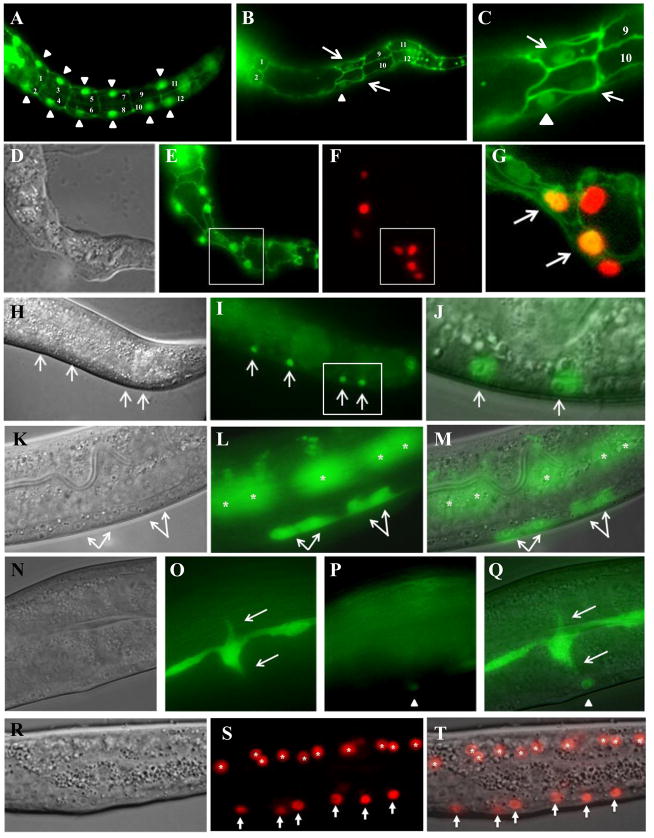

Another possibility was that in pax-3(rof) animals the P cells may partially or completely adopt the fate of other hypodermal cells, such as the lateral seam cells. To test this possibility, we performed pax-3 RNAi on a strain containing scm::gfp, a reporter expressed in the nuclei of all seam cells during embryonic and larval development (Köppen et al. 2001). Strikingly, we observed scm::gfp expression in some P cell nuclei in pax-3 RNAi treated early L1-stage animals, indicating these ventral hypodermal cells were expressing a marker of the lateral hypodermal (seam cell) fate (Figure 7A–C and data not shown). We also observed ectopic expression of scm::gfp in P cells in 27% of pax-3(ga96) animals raised at 25° (40/150 L1 animals). The P cells and their progeny never express this marker in wild type animals. To verify the expression in P cells during the L1 stage, pax-3 RNAi was performed on a strain harboring the pax-3p::mCherry transcriptional reporter, ajm-1::gfp, and scm::gfp reporters. pax-3p::mCherry expresses in a subset of P cells (P1, P2, P5 - P10), ajm-1::gfp marks hypodermal cell boundaries, and scm::gfp marks seam cell nuclei (note: since pax-3p::mCherry is a transcriptional reporter, pax-3 RNAi does not affect the expression of the transgene). We found that in 77% (30/39) of L1 animals observed with a severe body morphology defect, scm::gfp and pax-3p::mCherry reporter expression could be seen overlapping in cells close to the body morphology defect (Figure 7D–G). In wild-type animals expression of pax-3p::mCherry and scm::gfp never overlapped. Interestingly, the P cells that most often showed ectopic scm::gfp expression in the P cells in L1-stage animals (Figure 5C) were the same ones that showed the highest penetrance of the Dis phenotype (Figure 5B). Ectopic scm::gfp expression was also observed in P cell descendants in the L2, L3, and L4 stages of development (Figure 7H–J and data not shown). When scored in the L4 stage, the ectopic seam cell reporter expression was most often observed in the midbody and posterior of the animal (Table 5), again reflective of the pattern of Dis phenotype penetrance in the L1 cells (Figure 5B).

Figure 7. pax-3 reduction of function causes ectopic seam cell marker expression in P and Pn.p cells and misoriented seam cell processes.

(A–C) Wild-type (A) and pax-3 RNAi treated animals (B, C) expressing ajm-1::gfp and scm::gfp. (C) is close up of image in (B). Arrowhead point to an scm::gfp seam cell; arrows point to P cells ectopically expressing scm::gfp. (D–G) pax-3(RNAi) on pax-3p::mCherry; ajm-1::gfp; scm::gfp early L1-stage animal. (D) Nomarski image, (E) ajm-1::gfp (junctional) and scm::gfp (nuclear) expression, (F) pax-3p::mCherry (nuclear) expression, (G) merge of boxed region in (E) and (F) showing coexpression of scm::gfp and pax-3p::mCherry in the same P cell nuclei (arrows). (H–J) Posterior end of an L3-stage pax-3(RNAi) animal with ectopic scm::gfp expression in Pn.p cells along the ventral surface. (H) Nomarski image, (I) fluorescent image, (J) merge of boxed region in (I). (K–M) L4-stage pax-3(RNAi) animal with ectopic grd-10p::gfp expression in P3.p and P4.p descendants (arrows). The cells marked by asterisks are the seam cells out of focus. (K) Nomarski image, (L) fluorescent image, (M) merge of (K) and (L). (N–Q) L4-stage pax-3(RNAi) animal with seam cells extending processes (arrows) towards Pn.p nuclei misexpressing grd-10::gfp (arrowhead). (N) Nomarski image, (O, P) fluorescent image in two different focal planes, (Q) merge of (N) and (O). (R–T) Posterior of an L2-stage pax-3(RNAi) animal with ectopic egl-18p::mCherry reporter expression in Pn.p cells (arrows). Asterisks mark seam cells after division. (R) Nomarski image, (S) fluorescent image, (T) merge of (R) and (S). Anterior is to the left and dorsal to the top in all images.

Table 5.

expression of seam cell markers in ventral hypodermis in pax-3(rof) animals

| strain | Expression anterior | expression midbody | expression posterior | N | range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| scm::gfp control(RNAi) | 0% | 0% | 0% | 50 | 0 |

| scm::gfp pax-3(RNAi) | 5% | 26% | 40% | 57 | 2–8 |

| egl-18::mCherry control(RNAi) | 0% | 0% | 0% | 50 | 0 |

| egl-18::mCherry pax-3(RNAi) | 8% | 26% | 39% | 35 | 1–9 |

| grd-10::gfp pax-3(ga96) | 4% | 20% | 0% | 30 | 1–6 |

| scm::gfp pax-3(ga96) | 8% | 18% | 6% | 34 | 1–6 |

Seam cell reporter fluorescence (GFP, mCherry) in the ventral hypodermis was scored for the indicated strains at the L4 stage. Fluorescence-positive ventral hypodermal cells present anterior to the vulva, around the vulval opening, or posterior to the vulva were scored, and the percentage of each is indicated in columns 2 – 4. Column 5 shows the number of animals observed. Column 6 shows the range in number of fluorescent cells observed.

To validate this result we examined expression of two other seam cell markers, grd-10p::gfp (Hao et al. 2006) and egl-18p::mCherry (Liu et al. 2009), in pax-3(RNAi) animals. grd-10 encodes a hedgehog-like protein that is expressed in seam cells in all developmental stages (Aspöck et al. 1999). In agreement with the scm::gfp result, pax-3(ga96) animals showed ectopic expression of grd-10p::gfp in P cells and their descendants in all larval stages (Figure 7K–M, Table 5, and data not shown). Interestingly, the grd-10p::gfp reporter showed partial cytoplasmic localization of GFP in seam cells, and in rare cases we observed seam cells in pax-3(ga96) and pax-3 RNAi-treated animals extending processes towards nuclei of Pn.p cells missexpressing the grd-10p::gfp reporter (Figure 7N–Q).

egl-18 encodes a GATA-family transcription factor that is expressed in the seam cells throughout all developmental stages, and which is required to specify the seam cell fate initially in the embryo (Koh and Rothman 2001). We recently showed that egl-18 is a downstream target of a Wnt signaling pathway in the seam cells during their asymmetric larval divisions, and maintenance of egl-18 expression by Wnt signaling is required for one daughter to retain the seam cell fate (Gorrepati et al. 2013). As with scm::gfp and grd-10p::gfp, we found that both pax-3(ga96) and pax-3(RNAi) animals showed inappropriate high level expression of egl-18p::mCherry in P cell descendants in the larva (Figure 7R–T, Table 5).

These results indicated that cells of the ventral hypodermal P lineage in the larva misexpressed three markers of lateral hypodermal or seam cell fate when pax-3 function is reduced, two that are likely to be more terminal markers of the seam fate (grd-10p::gfp and scm::gfp) and one that is an early specification factor (egl-18p::mCherry). If the misexpressing ventral P cells were incorrectly adopting a lateral seam cell fate in pax-3 reduction-of-function animals, then expression of the seam cell terminal marker might be dependent on expression of the seam cell specification factor egl-18, as in wild type animals (Koh and Rothman 2001; Gorrepati et al. 2013). Indeed we found that reduction of egl-18 function in pax-3(RNAi) animals caused a large reduction in the penetrance of the ectopic grd-10::gfp expression phenotype: only 4% of egl-18(ok290) pax-3(RNAi) animals misexpressed grd-10p::gfp in the ventral hypodermis, compared to 33% of pax-3(RNAi) animals (Table 6). This indicates that the seam cell like behavior of the P cell progeny in pax-3(RNAi) animals is dependent on egl-18 function, as in normal seam cells. Taken together, these results suggests that the normal function of pax-3 may be to prevent the ventral hypodermal P cells from adopting a lateral hypodermal seam cell fate during embryonic and larval development, perhaps through direct or indirect repression of egl-18.

Table 6.

expression of seam cell markers in ventral hypodermis in pax-3(rof) animals is dependent on egl-18 function

| Strain | ectopic expression | N |

|---|---|---|

| scm::gfp control(RNAi) | 0% | 47 |

| scm::gfp pax-3(RNAi) | 33% | 105 |

| scm::gfp pax-3(RNAi); egl-18(ok290) | 4% | 113 |

Seam cell reporter fluorescence in the ventral hypodermis was scored for the indicated strains at the L4 stage and is indicated in columns 2. Column 3 shows that number of animals observed.

Ectopic expression of pax-3 causes the loss of a seam cell marker in seam cells

To test the hypothesis that pax-3 functions to repress expression of seam cell genes in the P cells, we asked if pax-3 is sufficient to prevent the normal expression of such genes in the seam cells themselves. We took two approaches to ectopically express pax-3 in seam cells. First, we expressed pax-3 globally in animals using a heat shock inducible promoter (hsp::pax-3). hsp::pax-3; grd-10::gfp worms were heat-shocked as mixed stage embryos, and at the time of the L1, L2 and L3 larval molts, and animals were scored at the mid-L4 stage for the number of grd-10p::gfp expressing nuclei. While no difference in grd-10p::gfp positive nuclei was observed for earlier time points, we did observe a significant decrease in the number of seam cells expressing grd-10p::gfp when PAX-3 was overproduced at the L2 and L3 molts, with some animals having as few as six GFP positive cells per side, compared to 16 GFP positive cells in animals not given a heat shock (Figure 8A – C; Table 7). As a second approach, we drove pax-3 expression specifically in the seam cells throughout development using the grd-10 promoter (grd-10p::pax-3) in animals also expressing the grd-10p::gfp seam cell marker. Similar to the heat-shock experiment results, the average number of gfp expressing nuclei was significantly reduced in grd-10p::pax-3; grd-10::gfp animals with an average of 11.1 GFP-expressing seam cells, with some animals having as few as two GFP positive cells, compared to an average of 16.1 for the control strain (Figure 8D and E, and Table 7). The seam cells produce a specialized external structure consisting of raised cuticular ridges called alae that run the length of the adult worm above the seam cell (Hall and Altun 2008). We found that in 100% of grd-10p::pax-3 animals that lacked grd-10p::gfp expression, there was a concomitant loss of alae production (Figure 8F–I). These results suggest that ectopic expression of pax-3 in the seam cells caused both loss of expression of a seam cell specific marker (grd-10pgfp), and loss of adoption of a differentiated seam cell phenotype (alae production), which is consistent with the hypothesis that the normal function of pax-3 is to repress seam cell fates in the ventral hypodermal P cells.

Figure 8. Ectopic pax-3 expression causes the loss of a seam cell marker and alae formation in seam cells.

The grd-10p::gfp transgene shows leaky cytoplasmic expression making it possible to view both the nuclei and cell boundaries of the seam cells. (A) Non-heat-shocked hsp::pax-3; grd-10p::gfp animal with 16 seam cell nuclei expressing grd-10p::gfp. (B, C) hsp::pax-3; grd-10p::gfp animals given a single heat shock at the L2/L3 molt (B) and L3/L4 molt (C) showing 11 and 6 grd-10p::gfp expressing nuclei, respectively. (D) grd-10::gfp animal showing 16 grd-10::gfp expressing nuclei (E) grd-10p::pax-3; grd-10::gfp animals showing 8 grd-10::gfp expressing nuclei. (F) Nomarski image of wild-type animal showing continuous stretch of alae (arrows) (G–I) Nomarski (G, H) and epifluorescent (I) images of the same animal showing the loss of alae formation where grd-10p::gfp expression is absent (arrow). The four lines in G mark the alae seen in H. All images are of mid-L4-stage worms and anterior is to the left and dorsal towards the top. Asterisks mark individual seam cell nuclei. SC – seam cells nuclei with gfp expression.

Table 7.

Ectopic and seam cell specific expression of pax-3 causes a reduction in seam cell reporter expression in the seam cells

| Strain | PAX-3 overexpression | GFP positive cells (range) | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| grd-10p::gfp; hsp::pax-3 | embryo −HS | 15.6 (13–18) | 150 |

| embryo +HS | 15.7 (13–18) | 150 | |

| L1/L2 −HS | 16.1 (14–18) | 162 | |

| L1/L2 +HS | 15.8 (10–19) | 166 | |

| L2/L3 −HS | 15.9 (13–19) | 164 | |

| L2/L3 +HS | 14.3 (6–18)* | 173 | |

| L3/L4 −HS | 16.0 (12–18) | 100 | |

| L3/L4 +HS | 12.7 (6–18)* | 100 | |

| grd-10p::gfp | continuous | 16.1 (14–18) | 52 |

| grd-10p::gfp; grd-10p::pax-3 | continuous | 11.1 (2–18)* | 84 |

The first column shows the strain tested and column 2 shows the time when hsp::pax-3; grd-10p::gfp animals were given a 30 minute heat shock at 37°C. Column 3 indicates the average number of grd-10p::gfp expressing lateral hypodermal nuclei on one side. Column 4 gives the number of animals scored.

t test, p< 0.0001.

Discussion

Here, we describe further characterization of the pvl-4(ga96) allele that was originally identified in an EMS mutagenesis screen for animals with a protruding vulva phenotype (Eisenmann and Kim 2000). Whole genome sequencing identified the molecular lesion in the pvl-4(ga96) strain as a point mutation (CCC to CTC) in exon 2 of the Paired-box transcription factor encoding gene pax-3, which causes a Pro29Leu change in an amino acid that is conserved in all PAX3 homologs. Consistent with pvl-4 being pax-3, we showed that a pax-3 transgene rescues numerous pvl-4(ga96) phenotypes and that pax-3(RNAi) phenocopies all tested pvl-4(ga96) phenotypes; we now refer to this gene and allele as pax-3(ga96).

PAX proteins are transcription regulators characterized by a 128 amino acid Paired DNA binding domain; some PAX proteins have a second DNA-binding domain, a 60 amino acid homeodomain. All members of this family are believed to have a transcription activation domain at the carboxy terminus, and some members have an octapeptide protein-protein interaction motif between the DNA binding domains (Blake and Ziman 2014). Based on sequence homology within the Paired DNA binding domain and the presence or absence of the homeodomain and octapeptide motif, the nine PAX proteins in vertebrates are divided into four classes consisting of PAX1/9, PAX2/5/8, PAX3/7, and PAX4/6. The C. elegans pax-3 gene encodes the only PAX protein with all three conserved PAX family motifs, and is the only PAX-3/7 family member in this nematode species (Hobert and Ruvkun 1999).

Members of the PAX family are present in both vertebrates and invertebrates where they function in cell fate specification and other processes during development (Chi and Epstein 2002; Paixão - Côrtes et al 2015). In vertebrates, PAX family members play a role in stem-cell proliferation, cell type specification and regionalization during embryogenesis (Chi and Epstein 2002; Blake et al. 2008; Blake and Ziman 2014). In particular the function of PAX family members during myogenesis and during the development of the vertebrate neural crest has been extensively studied. During myogenesis, PAX3 is expressed in early muscle precursors in the embryo and acts upstream of myogenic differentiation factors such as MyoD, Myf5 and Myogenin (Buckingham and Relaix 2015). Downregulation of PAX3 is required for terminal differentiation of muscle cells, and maintenance of PAX3 expression prevents terminal differentiation in muscle cell cultures (Buckingham and Relaix 2015). In a similar way, Pax3 is expressed early in the developing neural crest and acts upstream of several neural crest specifying genes. Consistent with this function, heterozygous loss of PAX3 results in defects in multiple neural crest derivatives in both the mouse Splotch mutant and in humans with Waardenburg syndrome (Monsoro-Burq 2015). Significantly, the proline to leucine mutation we identified in C. elegans pax-3 has been found in humans with Waardenburg syndrome (Pingault et al. 2010). Finally, in addition to their role during embryogenesis, some PAX family members are expressed in adult tissues and act in tissue regeneration and maintenance (Kozmik 2005).

C. elegans has five genes encoding PAX family members (vab-3/PAX6, egl-38/PAX5, pax-3/PAX3, K07C11.1/PAX1, and K06B9.5/PAX2) with at least one representative in each PAX class (Hobert and Ruvkun 1999). pax genes play a role in a variety of developmental processes in C. elegans including cell fate specification of head hypodermal cells and proper migration of the somatic gonad (vab-3) (Chisholm and Horvitz 1995; Nishiwaki 1999; Cinar and Chisholm 2004), cell fate specification of blast cells in the male tail (vab-3 and egl-38) (Chamberlin and Sternberg 1995; Chisholm and Horvitz 1995; Zhang and Emmons 1995; Chamberlin et al. 1997), cell fate specification and regulation of morphogenetic movements of the uterine and vulval cells (egl-38)(Chamberlin et al. 1997; Chamberlin et al. 1999; Chang et al. 1999; Rajakumar and Chamberlin 2007), and the regulation of programmed cell death in the germline and somatic cells (egl-38 and K06B9.5) (Park et al. 2006).

At the onset of this work, relatively little was known about the role pax-3 has in C. elegans. Genome-wide RNAi screens had shown that pax-3 RNAi-treated animals showed partially penetrant embryonic and larval lethality, exhibited variable body morphology defects, and had vulval phenotypes (Kamath et al. 2003; Simmer et al. 2003). Also, expression analysis in embryos and L1 stage larvae showed pax-3 reporter expression in AB-derived hypodermal cells in the embryo and expression in head hypodermal cells, neurons and blast cells along the body of L1 stage animals (Liu et al. 2009; Murray et al. 2012).

pax-3(ga96) mutant animals were identified based on their protruding vulva phenotype as adults (Eisenmann and Kim 2000), however pax-3(ga96) animals show embryonic and larval lethality, and animals that survive have mild to severe body morphology defects (Vab). In severe cases, newly-hatched pax-3(ga96) animals have a ‘Lumpy Dumpy’ phenotype, where the body of the larva appears to have improperly elongated: these animals may be unable to feed, which could account for the observed larval lethality. Previously we showed that all animals carrying pax-3(ga96) over a deficiency fail to survive, dying as either embryos or ‘Lumpy Dumpy’ L1 larvae ((Eisenmann and Kim 2000) and D. Eisenmann unpublished observations). Here, we show that ga96 is a hypomorphic, temperature sensitive allele of pax-3. Together these results suggest that the null phenotype of this locus is likely to be embryonic lethality. Consistent with an embryonic lethal phenotype, some pax-3(rof) embryos appear to have ventral enclosure defects, where the embryo appears open at the ventral cleft at the comma stage and extrusion of internal contents through the ventral surface is seen. We have observed pax-3 reporter expression in the leading cells and the pocket cells which are involved in the ventral enclosure process (K. Thompson and D. Eisenmann, unpublished observation) (Chisholm and Hardin 2005). Based on this, it is possible that pax-3 is acting in the specification of the head hypodermal cells or in the morphogenetic process of ventral enclosure. Supporting this hypothesis is that ectopic expression of PAX3 in human tissue culture cells causes actin enriched cellular lamellipodia and filopodia-like protrusions (Wiggan and Hamel 2002). Additionally, C. elegans homozygous for the deficiency mnDf29, which overlaps the pax-3 locus, have defects in the movement of ventral cells and fail to properly close the ventral surface of the embryo (Labouesse 1997). However a full characterization of the embryonic defects of pax-3(lof) animals will require the generation of a true pax-3 null allele. We note that a deletion allele that removes most of the third exon of pax-3, tm1771, was found by the C. elegans Deletion Mutant Consortium by random mutagenesis and PCR screening (Consortium 2012); unfortunately, we were unable to recover this allele from the starting strain.

Based on its vulval phenotype, we have focused most of our attention on the postembryonic role of pax-3 in the ventral hypodermal cells. In our previous preliminary characterization of pax-3(ga96) it was suggested that the vulval defects were due to a deficit in Pn.p cell number (Eisenmann and Kim 2000). However we report here that mutant animals also have defects in the number of Pn.a cell descendants, suggesting that the primary defect is in the P cells themselves. This is consistent with pax-3 reporter gene expression reported here and elsewhere (Liu et al. 2009; Murray et al. 2012) showing expression in the P cells in the embryo and the P cells and their descendants in the larva. Consistent with a function in the P cells, when we examined newly hatched pax-3(rof) L1-stage worms expressing the hypodermal junctional cell marker ajm-1::gfp, we observed two distinct P cell phenotypes. In pax-3(rof) animals displaying the Gap phenotype the overall shape and size of the double row of P cells appears roughly normal, however there is a loss of ajm-1::gfp expression between some P cells in early L1-stage animals. We believe there are still cells in this location because there is no herniation of internal tissue, and because pax-3(RNAi) L1 stage animals with the Gap phenotype still express the pax-3p::mCherry transcriptional reporter in P cell nuclei in their stereotypical positions (Kenneth Thompson, personal observation). Inappropriate cell fusion of the P cells as an explanation for this phenotype was ruled out based on the inability of eff-1 or aff-1 reduction-of-function to suppress the Gap phenotype (however, there could be an unidentified fusion protein or mechanism that is derepressed in pax-3 mutants animals). Nor do the cells appear to be undergoing inappropriate cell death, as occurs in animals lacking function of pax-3 in the nematode P. pacificus (see below; Yi and Sommer 2007). Another possibility, given the identity of PAX-3 as a transcription factor is that pax-3 may directly or indirectly affect ajm-1 expression, such that reduction of pax-3 would result in loss of expression of the ajm-1::gfp reporter. Additional experiments will be needed to determine the nature of this pax-3 phenotype in the P cells. The second phenotype we observed in pax-3(rof) L1-stage larva carrying the ajm-1::gfp reporter was that some P cells were misshapen, misaligned and made ectopic contacts with one another, in a manner never seen in wild type animals; we termed this Disorganized or Dis. We found overlap between the Dis phenotype for the P cells and a visible body morphology defect (lumps or bulges). The P cells most affected by the Dis phenotype were also the same ones that showed misexpression of a lateral fate marker (see below). We currently do not know how the Gap and Dis phenotypes observed in newly hatched L1s relate to the reduced Pn.p cell number phenotype we previously characterized (Eisenmann and Kim 2000). It is possible that some P cell or Pn.p cell nuclei do not end up in the same plane as the other P cell descendants in the ventral cord, thereby leading to the phenotype of ‘missing’ Pn.p cells observed previously. However beyond the cell fate specification defect observed in some P cells (see below), the proximate cause of the missing Pn.p nuclei is still unclear.

It is not clear whether the Gap and Dis phenotypes are related or separate, however both phenotypes are indicative of the P cells behaving in an abnormal manner when pax-3 function is reduced. Consistent with this, we observed ectopic expression of three markers of the seam cell fate in the larval P cells and their descendants in pax-3(rof) animals, suggesting the P cells and/or their descendants are adopting some elements of the seam cell fate when pax-3 function is compromised. Three other observations support this hypothesis. First, the ectopic expression of grd-10p::gfp in pax-3(rof) animals was dependent on egl-18 function, as expected if the cells were adopting a lateral seam fate. Second, in rare animals seam cells were seen sending cellular protrusions towards P cells with ectopic seam cell marker expression. During larval development, after a seam cell division, the daughters that retain the seam cell fate extend lateral protrusions toward neighboring seam cells until contact is restored; it is possible that this same activity is being directed toward P cells expressing a partial seam cell fate in pax-3 mutants. Finally, at the L4-stage, in pax-3 reduction-of-function L4-stage animals we observed as many as 9 Pn.p descendant nuclei in the posterior of the animal ectopically expressing seam cell reporters. Since there are only six P cell descendants in wild type animals in this region, this suggests some Pn.p cells expressing the scm::gfp marker may have divided and produced more cells than are typically found in the posterior ventral region. In conclusion, it appears that compromising pax-3 function causes some ventral hypodermal P cells and their descendants to adopt several aspects of the lateral hypodermal seam cell fate.

The expression of seam cell markers in the ventral hypodermis in pax-3 reduction-of-function animals is consistent with two functions for PAX-3 in the ventral cells. First, PAX-3 could be required to maintain the ventral hypodermal fate in these cells, and in its absence, they might express genes associated with other hypodermal fates. Second, PAX-3 could act to specifically repress lateral fate genes in the ventral hypodermal cells. This function would be consistent with the presence of an octapeptide motif in PAX-3, which is known to act as a transcriptionally repressive protein domain (Mayran et al. 2015). When pax-3 was ectopically expressed in the seam cells, we observed loss of expression of a seam cell reporter (grd-10p::gfp) in seam cell nuclei, indicating that pax-3 is sufficient to suppress expression of a lateral hypodermal cell fate gene in the seam cells themselves. In rare cases in these animals, we also noted seam cells appeared rounded in shape (like P cells) and lacked lateral protrusions toward their seam cell neighbors (K. Thompson and D. Eisenmann, unpublished observation). Taken together with our other results, we believe this argues that the function of pax-3 is to protect the ventral hypodermal P cells from adopting the fate of the lateral hypodermal seam cells during normal development, perhaps by inhibiting expression of regulators of the lateral hypodermal fate (such as egl-18) in the ventral hypodermal cells during early development. This role for pax-3 in C. elegans is similar in some ways to the role of PAX3 in vertebrate development. For example, during vertebrate myogenesis PAX3 is expressed early in early muscle precursors, but must be turned off for those precursors to exit the cell cycle and differentiate (Buckingham and Relaix 2015). It is believed the role of PAX3 in these cells is to prevent early cells from differentiating prematurely. In the same way, we believe C. elegans PAX-3 acts in the early ventral hypodermis to prevent these cells from differentiating as an incorrect hypodermal cell type.

In addition to the question of the exact nature of the defect in P cells exhibiting the Gap and Dis phenotypes in pax-3(rof), other intriguing questions remain. For example, one curious aspect of the pax-3 expression we observed is that reporter expression is seen in two seam cells (V3 and T) during embryogenesis. We have not yet investigated the relevance of pax-3 expression in these seam cells but it is interesting that the seam cells that express pax-3 are in close proximity to P cells that do not express pax-3 (P11/12) or to P cells that lose pax-3 expression by the time of L1 hatching (P3/4). We note that P3/4 are also the P cells that are most affected by the Gap phenotype. Based on these observations, we think it is possible that V3 and T may be influencing these P cells in a cell non-autonomous manner. Another intriguing question given the important role of pax-3 in cell fate specification in the ventral hypodermal cells is the identity of the factors responsible for expression of pax-3 in those cells. Expression of pax-3 reporters is first observed in the mother cell that divides to give rise to the pax-3-expressing ventral hypodermal cells, suggesting it is specifically turned on in this lineage. In preliminary work, we have identified a 290 bp enhancer element from the pax-3 upstream region that is necessary and sufficient for reporter expression in the embryonic P cells. (C. Kang, K. Thompson and D. Eisenmann, unpublished observations). The identification of factors binding this element should shed additional light on the process of early hypodermal cell fate specification in the embryo.

A final intriguing issue is the difference in the role of PAX-3 in the related nematode species P. pacificus. Significantly, work done in the nematode species Pristionchus pacificus showed that pax-3 functions in ventral cell fate specification during development of the vulva (Yi and Sommer 2007). In pax-3 mutants the central Pn.p cells that form the Vulval Equivalence group die by programmed cell death. However a more posterior Pn.p cell that normally undergoes a programmed cell death, survives in pax-3(rof) in Pristionchus. pax-3 is downstream of LIN-39 in the former process but not the latter. Thus in P. pacificus pax-3 functions in two different ventral hypodermal cell types, regulating their cell fate specification. Our C. elegans pax-3 allele also causes defects in vulval induction but the underlying cellular cause is different between the two nematode species: the defect in Pn.P cell numbers originally found in pax-3(ga96) animals is not due to the inappropriate cell death of P cells or Pn.p cells as in P. pacificus but rather to their adoption of an incorrect cell fate. In both species the affect on the ventral hypodermal cells when pax-3 function is reduced can be seen as a cell fate transformation, however in P. pacificus it is a transformation of central Pn.p cells to the fate of more posterior Pn.p cells, while in C. elegans it appears to be a transformation earlier in development, of the ventral hypodermal P cells to the fate of their lateral hypodermal neighbors, the seam cells.

Additional work in P. pacificus has shown that pax-3 functions in muscle development in that species (Yi et al. 2009), which is a role strongly conserved with PAX-3 proteins in vertebrates (Buckingham and Relaix 2015). Curiously we have seen no evidence of a function for C. elegans pax-3 in muscle development based on examination of either pax-3(ga96) animals or pax-3(RNAi) animals. While strong loss of C. elegans pax-3 function leads to embryonic lethality and a Lumpy Dumpy phenotype at hatching, we have interpreted this as defects in hypodermal cells, as three different pax-3 reporters show expression predominantly in hypodermal cells in the embryo. Although there are several unidentified cells that express pax-3 in the early C. elegans embryo, it is clearly the case that the majority of muscle precursors do not express these reporters. Therefore, to date we have no evidence that the myogenic role of pax-3 is conserved in C. elegans. Interestingly, as previously pointed out (Yi and Sommer, 2007), P. pacificus pax-3 and C. elegans pax-3 do not share a common gene structure, suggesting that extensive change in the structure of the pax-3 gene, and perhaps its regulation, may have occurred during the divergence of these two nematode species.

In summary, here we have shown that the C. elegans PAX family member PAX-3 plays an important role in the specification of one of the three major hypodermal cell types, the ventral hypodermis. Starting with the vulval phenotype by which a mutation in pax-3 was initially identified, we went on to show that in animals with reduced pax-3 activity there are morphological defects in the ventral hypodermal P cells at hatching, and some P cells and their progeny misexpress markers of the lateral hypodermal fate in larvae, suggesting that one function of pax-3 is to protect the ventral hypodermal cells from adopting a lateral cell fate. No factors were previously known to be specifically required in the ventral hypodermal cells, so we believe pax-3 represents the first instance of a factor required for proper specification of this important early hypodermal cell type in the worm. This insight and additional work should help us further unravel the network of factors required for the specification and diversification of the major hypodermal cell types in the early C. elegans embryo.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

A mutation affecting the C. elegans homolog of the transcription factor PAX3 was identified, and is identical to a human mutation associated with Waardenburg syndrome

pax-3 reduction of function leads to ventral embryonic hypodermal cells adopting the fate of lateral embryonic hypodermal cell (lateral)

pax-3 is the first gene required for specification of the ventral hypodermal fate in the C. elegans embryo

Unlike vertebrates or another nematode, P. pacificus, a role for pax-3 in myogenesis was not observed in this species

Acknowledgments

We thank, A. Golden, I. Greenwald, I. Hamza, S. Kim, D. Miller and J. Rothman for sharing reagents and strains and we thank Wormbase for as a valuable resource of information. Some nematode and yeast strains used in this work were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center that is funded by the NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440), and by the National BioResource Project of Japan. This work was supported by a National Science Foundation (NSF) grant IBN-0131485, funding from The University of Maryland Baltimore County, and the intramural program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no actual or potential conflict of interest including financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence, or be perceived to influence, the work reported here.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information