Abstract

Cholecystokinin (CCK) is secreted by neuroendocrine cells comprising 0.1%–0.5% of the mucosal cells in the upper small intestine. Using CCK promoter-driven green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression in transgenic mice, we have applied immunofluorescence techniques to analyze the morphology of CCK cells. GFP and CCK colocalize in neuroendocrine cells with little aberrant GFP expression. CCK-containing cells are either flask- or spindle-shaped, and in some cells, we have found dendritic processes similar to pseudopods demonstrated for gut somatostatin-containing D cells. Most pseudopods are short, the longest process visualized extending across three cells. Pseudopods usually extend to adjacent cells but some weave between neighboring cells. Dual processes have also been observed. Three-dimensional reconstructions suggest that processes are not unidirectional and thus are unlikely to be involved in migration of CCK cells from the crypt up the villus. Abundant CCK immunostaining is present in the pseudopods, suggesting that they release CCK onto the target cell. In order to identify the type of cells being targeted, we have co-stained sections with antibodies to chromogranin A, trefoil factor-3, and sucrase-isomaltase. CCK cell processes almost exclusively extend to sucrase-isomaltase-positive enterocytes. Thus, CCK cells have cellular processes possibly involved in paracrine secretion.

Keywords: Cholecystokinin, Green fluorescent protein, I cells, Pseudopods, Paracrine, Mice, transgenic

Introduction

Cholecystokinin (CCK) is a peptide hormone secreted from individual endocrine cells (termed I cells) in the mucosal epithelium of the small intestine in response to intraluminal nutrients (Liddle 1997). The physiological actions of CCK include stimulation of pancreatic secretion and gallbladder contraction, regulation of gastric emptying, and induction of satiety (Liddle 1994). Based on immunocytochemical staining studies at the light- and electron-microscopical levels and by transmission electron microscopy, nutrients in the lumen of the small intestine have long been thought to interact with the apical brush border of CCK cells. This interaction would then lead to an unknown cytoplasmic signal transduction mechanism, resulting in the exocytosis of CCK from the basolateral plasma membrane of I cells and subsequent dissemination throughout the body either locally by diffusion or systemically by bulk flow in the circulatory system. The ultrastructure of CCK cells supports this concept because these cells extend from the basement membrane within the mucosal epithelium to the lumen of the intestine and exhibit apical microvilli (the brush border), which are well-placed to sample luminal contents, and basally localized membrane-bound cytoplasmic granules containing CCK, which are well-placed to be secreted basolaterally by exocytosis (Buchan et al. 1978).

Recently, a novel model has become available for studying CCK cells in the brain; we have used this model to study CCK in the intestine. Transgenic CCK-green fluorescent protein (GFP) mice have been developed by the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center (MMRRC, University of Missouri). In these mice, enhanced GFP expression is driven by the CCK promoter resulting in green fluorescence only in CCK cells (Samuel et al. 2008). In addition to CCK-producing cells in the brain, the endocrine CCK cells in the small intestines of these mice are easily visible in a fluorescence microscope. In the process of assessing the distribution of these cells throughout the intestine, we have noticed an unusual structural feature in many of them, namely, a basal cell process resembling a pseudopod that seems to project some distance away from the originating cell. These processes resemble structures previously described in gastrointestinal somatostatin cells (Larsson et al. 1979). In the case of gut somatostatin cells, a key to understanding the functional significance of their basal cell processes is the identification of the cell types to which the processes extend. Based initially on showing that somatostatin basal cell processes come into close contact with these target cell types, somatostatin has been demonstrated to regulate, in the stomach, gastrin secretion from G cells and acid secretion from parietal cells (Alumets et al. 1979). Therefore, the aims of the present study have been to document the existence of basal CCK cell processes in the mouse intestine and to identify the intestinal cell types that they contact, with the ultimate goal of ascertaining the functional significance of these structures.

Materials and methods

Animals

Transgenic CCK-GFP mice were procured from MMRRC (University of Missouri, Columbia, Mo., USA). They were bred in-house by mating them with wild-type Swiss Webster mice (Charles River, Wilmington, Mass., USA). The obtained transgenic mice were genotyped by using the protocol provided by MMRRC. Animal care and experiments were carried out in accordance with institutional guidelines. Animals were fasted overnight with ad libitum access to water prior to harvesting the small intestine.

Immunofluorescence

Mice were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine and xylazine and perfused intracardially with ice-cold, freshly depolymerized 3.5% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, 0.9% NaCl). The proximal 10 cm of the intestine were removed, flushed, and post-fixed in 3.5% paraformaldehyde for 3 h at 4°C. The tissue was washed in PBS (30 min at 4°C), sequentially equilibrated in cold 10%, 20%, and 30% sucrose in 0.1M sodium phosphate pH 7.4 and flash-frozen in Tissue-Tek OCT compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, Calif., USA). Transverse sections (5 μm thick) were collected by using a cryostat set at −19°C and mounted on Super Up-Rite microscope slides (Thermo Scientific, Mass., USA).

Table 1 lists the antisera used, the suppliers, antibody-specific staining conditions, and references to their specificities. The CCK antiserum was raised in rabbits against CCK 19–36, affinity purified, and characterized in our laboratory. Cell-type-specific antisera were used to identify and localize the various cell types found in the mucosal epithelium of the small intestine: (1) chromogranin A for enteroendocrine cells, (2) trefoil factor-3 for goblet cells, and (3) sucrase-isomaltase for enterocytes. In addition, an antiserum specific for the CCK-1 receptor was used in an attempt to localize possible mucosal CCK target cells. In general, sections were post-fixed in either 10% formalin for 10 min at 4°C (CCK, GFP, trefoil factor-3, and chromogranin A) or in a 50% mixture of acetone and methanol (sucrase-isomaltase and GFP) for 10 min at −5°C and air-dried for 30 min. They were then rinsed with PBS or TBST (10 mM TRIS, pH 7.4, 0.9% NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100) for 5 min, and non-specific staining was blocked by incubating the sections in 10% donkey serum for 30 min at room temperature. The serum was drained away, and the sections were incubated with primary polyclonal antibody either overnight at 4°C or for 1 h at room temperature. After washes with PBS or TBST (3×5 min each), sections were incubated with secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Slides were rinsed in PBS or TBST (3×5 min each), counterstained with 2 μg/ml 4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Biochemika, Germany) and mounted in Prolong Gold anti-fade reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif., USA). Negative controls included slides treated with either primary or secondary antisera alone.

Table 1.

Primary and secondary antibodies used in immunofluorescence analysis (CCK cholecystokinin, GFP green fluorescent protein, PBS phosphate-buffered saline, TBST TRIS-buffered saline containing 0.1% Triton X-100)

| Primary antibody | Species | Source | Buffer | Dilution | Secondary antibody | Source | Dilution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCK (aa 19–36) | Rabbit | BioSource | PBS/TBST | 1:2000 | Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit | Jackson ImmunoResearch | 1:1000 | |

| CCK (aa 19–36) | Rabbit | BioSource | PBS/TBST | 1:2000 | Dylight-488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit | Jackson ImmunoResearch | 1:1000 | |

| CCK-1 Receptor | Rabbit | J. Walsh | TBST | 1:50 | Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit | Jackson ImmunoResearch | 1:1000 | Sternini et al. (1999) |

| Chromogranin A | Rabbit | Abcam | TBST | 1:1000 | Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit | Jackson ImmunoResearch | 1:1000 | Duckworth and Pritchard (2009) |

| GFP | Chick | Abcam | PBS/TBST | 1:1000 | Dylight-488-conjugated donkey anti-chick | Jackson ImmunoResearch | 1:1000 | Thompson et al. (2009) |

| GFP | Rabbit | V. Bennett | PBS/TBST | 1:1000 | Dylight-488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit | Jackson ImmunoResearch | 1:1000 | Kizhatil et al. (2009) |

| Intestinal Trefoil Factor-3 | Goat | Santa Cruz | PBS | 1:100 | Alexa-568-conjugated donkey anti-goat | Invitrogen Corporation | 1:1000 | Nishida et al. (2009) |

| Sucrase-Isomaltase | Goat | Santa Cruz | TBST | 1:500 | Alexa-568-conjugated donkey anti-goat | Invitrogen Corporation | 1:1000 | Gracz et al. (2010) |

Image acquisition

Images were collected by using Zeiss LSM software. Samples were imaged on a Zeiss inverted confocal microscope with 40×/1.3 oil (Zeiss Plan NeoFluar) or 63×/1.4 oil (Zeiss Plan Apochromat) objectives. Single optical sections or Z-stacks were acquired by sequential multi-tracking with excitation set at 405 nm (DAPI), 488 nm (endogenous GFP or Dylight 488), and 561 nm (Cy3 or Alexa 568) and emission filters of BP 420–480, BP505–550, and LP575, with pinholes set to 1 airy unit for each channel and line averaging of 8 or 16 at 1024 or 2048 pixel resolution. Transmitted light confocal differential interference contrast images were also collected.

Three-dimensional visualization

Sections of intestinal tissue (15 μm) were stained for GFP and CCK as described above. Immunostained sections were examined by using a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope with a Plan-Apochromat 63×/1.4 oil objective and 1.2× optical zoom. Three-dimensional multi-channel visualization and export as Quicktime movies were carried out by using Volocity Visualization software (PerkinElmer, Waltham, Mass., USA). The digital contrast and transparency of entire individual channels were adjusted to optimize the structure of the whole volume of the tissue imaged. Median filters (3×3) were applied to reduce the noise in some channels. Channels were visualized as either maximum intensity projections (green/GFP, red/CCK), which allowed the color to be seen through other channels, or as fluorescence (blue/DAPI).

Results and discussion

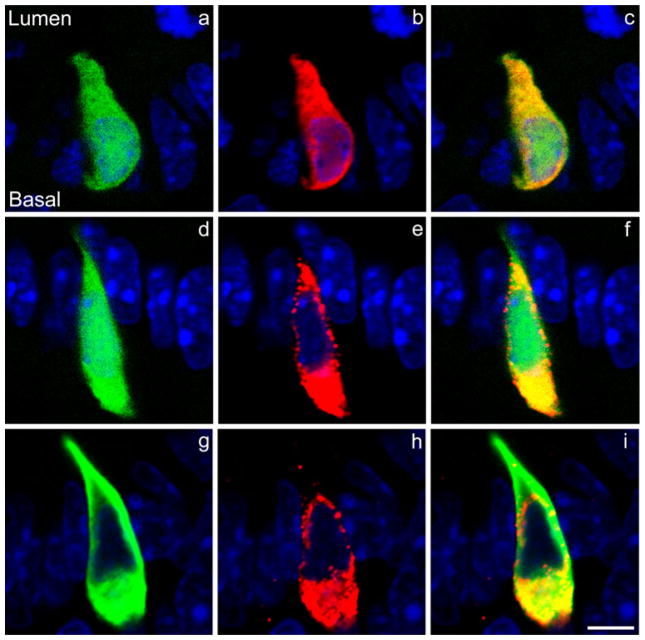

Endogenously expressed GFP driven by the CCK promoter filled the cytoplasm of the enteroendocrine CCK cells (I cells) in the mouse small intestine (Fig. 1). Nearly all cells identified by immunostaining with an antiserum for CCK also expressed GFP, indicating that GFP expression in the transgenic mouse was “clean”; only rarely did a GFP cell not stain positively for CCK (Fig. 2). The intensity of the endogenous green fluorescence observed in the CCK cells was variable and often weak. Therefore, in order to facilitate double-immunofluorescence staining in these cells, we tested the abilities of GFP antisera to stain endogenous GFP-expressing CCK cells in the mouse small intestine. Antisera raised against GFP from both rabbit and chicken stained CCK cells expressing GFP (Fig. 1). In subsequent studies, both the rabbit and the chicken anti-GFP sera were used to stain CCK cells.

Fig. 1.

Colocalization of CCK (cholecystokinin) and GFP (green fluorescent protein) in mouse intestinal CCK cells. a Endogenously fluorescent GFP (green) in a CCK cell. b The same CCK cell as seen in a stained with a rabbit GFP antiserum (red) demonstrating that only cells endogenously expressing GFP stain positively for GFP in the mouse duodenum. c Merged images of a, b. d Endogenously fluorescent GFP in a CCK cell. e The same cell as seen in d stained with a rabbit CCK antibody demonstrating that only CCK cells express GFP in the mouse duodenum. f Merged images of d, e. g CCK cell in which endogenous GFP has been visualized by immunostaining with an anti-GFP serum raised in chickens. h The same CCK cell as seen in g stained with a rabbit CCK antibody demonstrating that GFP and CCK can be immunostained by using primary antisera derived from a different species. i Merged images of g, h. The orientation of the CCK cells relative to the lumen of the intestine and the base of the cells is shown in a and is the same in all other panels (blue DAPI nuclear staining). Bar 5 μm

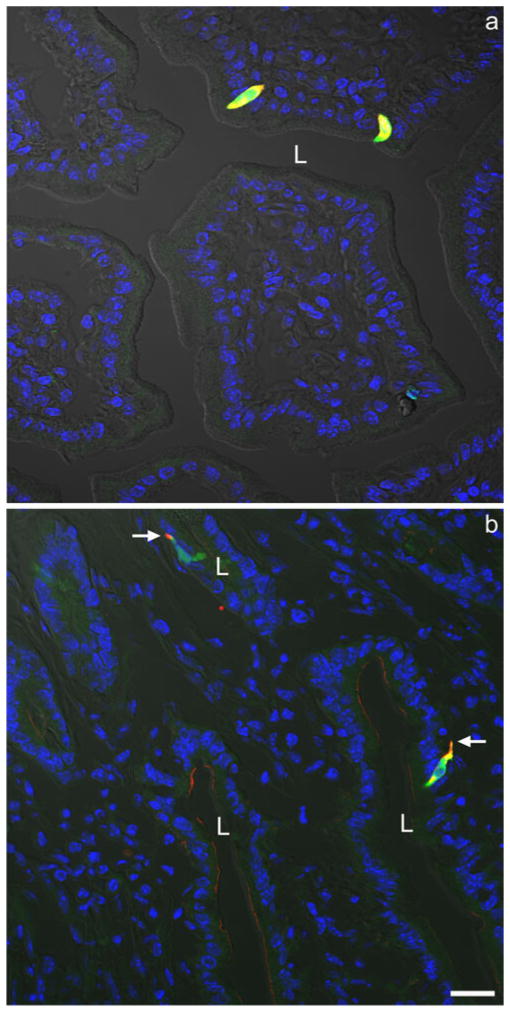

Fig. 2.

a Two yellow CCK cells at low power exhibiting both endogenous GFP expression (green) and positive immunostaining for GFP with a rabbit anti-GFP serum (red). b Two yellow CCK cells at low power exhibiting both positive immunostaining for CCK with a rabbit anti-CCK serum (red) and for GFP with a chicken anti-GFP serum (green). Note the basal CCK cell processes (arrows). Both photomicrographs were taken with fluorescence (blue DAPI nuclear staining) and differential interference contrast (DIC) optics (L lumen). Bar 20 μm

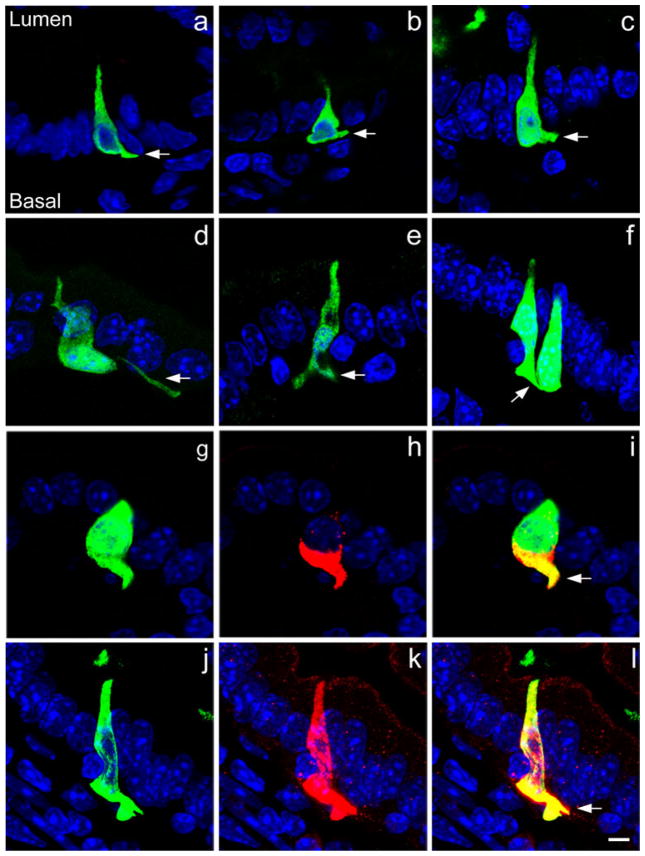

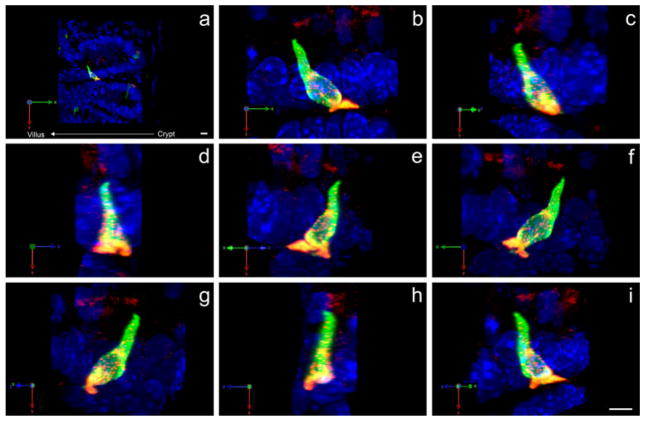

CCK cells were either flask- or spindle-shaped and were more abundant in intestinal crypts than in villi. We observed pseudopod-like basal cellular processes in many CCK cells (Fig. 3). In order to estimate the incidence of basal cellular processes among CCK cells, we counted cells that were both CCK- and GFP-immunopositive in six cross sections of duodenum. In crypts of Lieberkühn, 47 of 106 such cells exhibited detectable basal cell processes (47%). In villi, 73 of 112 CCK cells exhibited basal cell processes (65%). Most of the basal cell processes were short; the longest process visualized (about 15 μm) extended across three neighboring cells. Abundant CCK immunostaining was present in the basal cell processes, suggesting that they might release CCK onto nearby target cells. In crypts, basal cell processes usually extended to the adjacent cell. In villi, the processes were sometimes curved and wove between neighboring cells. Often a single extension bifurcated into two (Fig. 3e), and multiple processes were seen in a small percentage of the cells (25 out of 75 CCK cells with basal processes). Three-dimensional reconstructions of thicker sections (15 μm) suggested that these processes extended in all directions, and that they were probably not used in the migration of CCK cells from the crypt up the longitudinal axis of the villus (Fig. 4). These reconstructions also indicated that the percentage of CCK cells observed to have basolateral process might have been artificially low since processes can extend into Z-planes and thus be invisible through XY observation of a 5-μm-thick section. This possibility was minimized in the analysis by carefully focusing up and down through each CCK-immunoreactive cell to assess cell processes extending in all directions.

Fig. 3.

a–f Examples of CCK-GFP cells stained with chick or rabbit GFP antiserum extending basal cell processes (arrows) to neighboring cells. g–i, j–l Two examples of colocalization (yellow) of CCK (red) with chick GFP (green) in the basal cell processes of CCK cells. CCK is present in the pseudopods (arrows) together with GFP (blue DAPI nuclear staining). Bar 5 μm

Fig. 4.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of a CCK cell located at the base of a villus (a). The same cell (shown in all panels) possesses a bifurcated pseudopod that extends into spaces other than immediately up or down the crypt-villus axis (b–i). GFP is immunostained with chick GFP antibody (green) and CCK with rabbit CCK antibody (red). Both fluorophores are represented as maximum projections (blue DAPI nuclear staining). X-axis, Y-axis, and Z-axis (green, red, and blue, respectively) are shown (bottom left) to demonstrate that each image (b–i) is rotated 45° along the Y-axis. The crypt-villus axis is directly opposite the X-axis. Bars 10 μm (a), 5 μm (i)

In order to identify the cell type or types targeted by the processes, sections were co-stained with antibodies to chromogranin A (a neuroendocrine cell marker), trefoil factor-3 (a goblet cell marker), and sucrase-isomaltase (an enterocyte cell marker). Since we never observed a pseudopod of more than ~15 μm in length, we categorized cells as residing within 1–4 cells or >4 cells away from CCK-GFP cells in order to estimate the likelihood of CCK cells signaling to a particular cell type. As summarized in Table 2, we found that CCK-GFP cells were occasionally present near other CCK cells but rarely close to other neuroendocrine cells. Goblet cells were more commonly found within 4 cells of GFP-positive cells but this probably reflected the relative abundance of goblet cells relative to neuroendocrine cells in the small intestinal mucosa (Fig. 5). We never observed a pseudopod actually ending adjacent to a goblet cell (Fig. 6). In contrast, CCK-GFP cells and their basal cell processes always lay near to enterocytes (Fig. 7).

Table 2.

Proximity of CCK-GFP-positive cells to other cell types within the intestinal mucosa of villi. Intestinal sections were stained with antisera directed against chromogranin A, intestinal trefoil factor-3, or sucrase-isomaltase. The proximity of neuroendocrine cells, goblet cells, or enterocytes, respectively, to CCK cells was ascertained by determining if they resided within 1–4 cells or >4 cells away from GFP-positive (GFP+) cells seen in the same section. At least 100 cells of each type were counted. Results are expressed as the percent of total cells counted

| Antigen | Proximity to GFP+ cells

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Within 1–4 cells (%) | >4 cells away (%) | Total (%) | |

| Non-GFP chromogranin-positive | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| Intestinal trefoil factor-3 | 10 | 90 | 100 |

| Sucrase-isomaltase | 100 | 0 | 100 |

| GFP (CCK cells) | 4 | 96 | 100 |

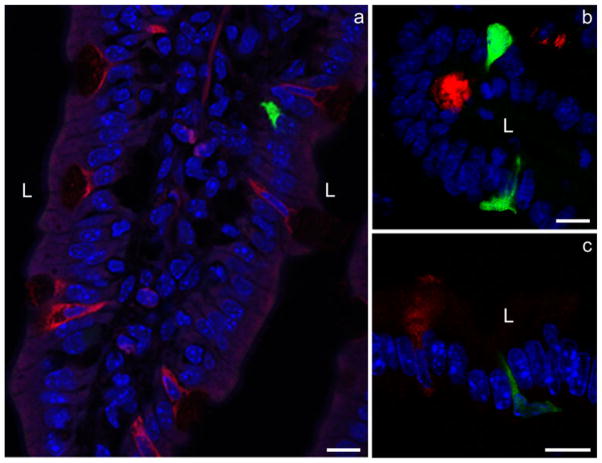

Fig. 5.

Double-immunofluorescence staining of sections with antibodies against intestinal trefoil factor-3 (red) to identify goblet cells and with either CCK or rabbit GFP antibodies (green). The basal CCK cell processes do not contact the goblet cells positive for intestinal trefoil factor-3 (L lumen, blue DAPI nuclear staining). Bar 10 μm

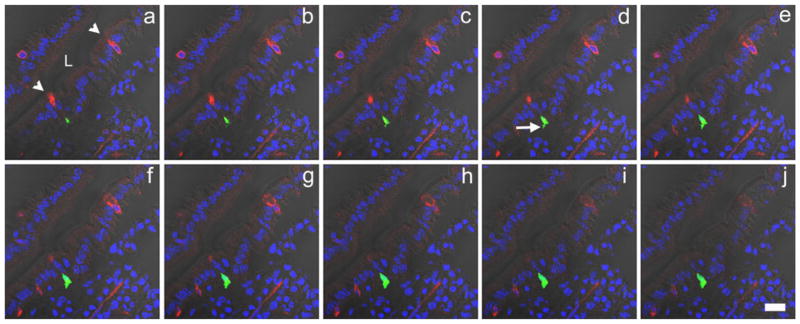

Fig. 6.

A series of Z-stack images (a–j: 0.49 μm apart) of a portion of the mouse duodenum double-stained for GFP (green) in CCK cells and intestinal trefoil factor-3 (red) in goblet cells to demonstrate that CCK basal cell processes are not directed to goblet cells (arrowheads goblet cells positive for intestinal trefoil factor-3, arrow basal CCK cell process, L lumen). Photomicrographs were taken with both fluorescence and DIC optics (blue DAPI nuclear staining). Bar 20 μm

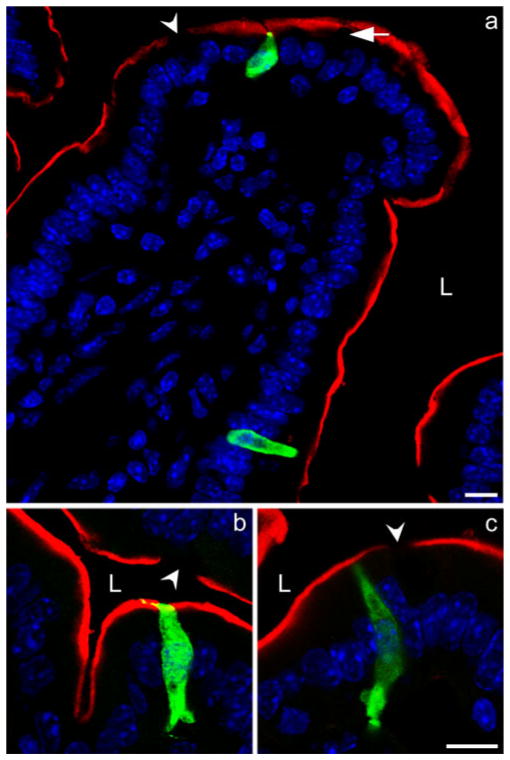

Fig. 7.

Double-immunofluorescence staining of sections with antibodies to sucrase-isomaltase (red) to identify enterocytes and rabbit GFP (green) to identify CCK cells. CCK cells and their basal cell processes are seen to be closely associated with the neighboring enterocytes. Depending on the plane of the section, either no sucrase-isomaltase staining (arrowheads) or faint staining is seen when a goblet cell (arrow) is present (L lumen, blue DAPI nuclear staining). Bar 10 μm

Gut somatostatin cells have been shown to extend basal cytoplasmic processes out to neighboring cell types and to release somatostatin from these pseudopod-like structures (Larsson et al. 1979). These cells are thought to release somatostatin by exocytosis from the basolateral processes followed by diffusion across small distances (a paracrine action) to interact with somatostatin receptors on target cells. By using this anatomical pathway, effective concentrations of somatostatin can be delivered relatively rapidly to specific target cells. In the stomach, this paracrine somatostatin pathway is well known to regulate gastrin secretion and hydrochloric acid secretion (Alumets et al. 1979). The basal cytoplasmic cell processes of these paracrine somatostatin cells end in bulb-like swellings (Alumets et al. 1979). Similar basal cytoplasmic cell processes have been observed in intestinal peptide YY (PYY) cells (Karaki et al. 2006; Lundberg et al. 1982). Moreover, the long slender basal processes described on cells in the rat ileum stain with an antiserum against the stomach hormone, gastrin (Larsson and Rehfeld 1978). The functional significance of these structures on PYY and gastrin cells is unknown.

Some of the actions of intestinal CCK are thought to be mediated by vagal afferent neurons (Dockray 2009). Thus, the basal cytoplasmic CCK cell processes observed in the present study might be directed at nearby vagal afferent neuronal endings beneath the basal lamina of the intestinal mucosal epithelium. However, several lines of evidence suggest the lack of close anatomical contact between CCK cells in the mucosal epithelium of the small intestine and enteric nerves. Few rat CCK cells lie in close anatomical contact (<5 μm) with vagal afferent axons, and the latter do not produce terminal specializations near CCK cells (Berthoud and Patterson 1996). The immunocytochemical localization of CCK-A receptors (now termed CCK-1 receptors) in the rat small intestine has revealed abundant expression in neuronal cell bodies and fibers but not in nerve terminals innervating the mucosa in which CCK cells are located (Sternini et al. 1999). We have repeated the rat study of Sternini et al. (1999) in our mouse model and, using the same CCK receptor antiserum, have been able to confirm the lack of CCK-receptor-expressing neurons in the duodenal mucosa (data not shown). Autoradiographic localization of saturable CCK radioligand binding has not revealed CCK receptors in the mucosa of the canine small intestine (Mantyh et al. 1994). Consistent with these findings, we have found no CCK-1 receptor staining in cells of the intestinal mucosa (data not shown). These observations suggest that CCK cells do not exert direct neurocrine action on enteric nerves but do not preclude paracrine action.

Since most CCK cells seem to direct their basal cell processes toward adjacent or nearby enterocytes, we can logically speculate whether CCK is released from these processes to affect enterocytes. The main functions of enterocytes are the absorption and secretion of fluids and the transport of ions, vitamins, and products of nutrient digestion. Our examination of the literature has not revealed any published descriptions of the effects of CCK on these enterocyte functions. However, the analysis of adult mouse tissues by reverse transcription with the polymerase chain reaction has revealed the expression of the CCK1 receptor (also known as the CCK-A receptor) in the duodenum, small intestine (presumably jejunum or ileum), and colon (Lacourse et al. 1997). This analysis has not identified the intestinal cell type expressing the CCK1 receptor, and so this molecular analysis may simply reflect the well-known expression of CCK1 receptors by vagal afferent nerves present within the walls of the small intestine and colon (Sternini et al. 1999).

Another interpretation of the functional significance of basal CCK cell processes in the small intestine is possible. The luminal perfusion of the rat small intestine with lipids has been shown to stimulate increased CCK secretion, and this effect is blocked by pretreatment with the drug, Pluronic L-81, which inhibits chylomicron formation (Raybould et al. 1998). Thus, the basal CCK cell processes described here might function to receive information from enterocytes, rather than to signal to enterocytes. This concept is also supported by the lack of bulb-like swellings at the ends of the basal CCK cell processes, unlike those observed at the ends of basal somatostatin cell processes, which are known to function in paracrine signaling (Alumets et al. 1979). Interestingly, another small intestinal endocrine cell that is stimulated by ingested lipids, the PYY cell, also exhibits basal cell processes (Karaki et al. 2006; Lundberg et al. 1982). Future studies should distinguish between these various possibilities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant DK38626.

The authors thank Sam Johnson for his help with image acquisition and acknowledge Duke University’s Light Microscopy Core Facility.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00441-010-0997-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- Alumets J, Ekelund M, El Munshid HA, Hakanson R, Loren I, Sundler F. Topography of somatostatin cells in the stomach of the rat: possible functional significance. Cell Tissue Res. 1979;202:177–188. doi: 10.1007/BF00232233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud HR, Patterson LM. Anatomical relationship between vagal afferent fibers and CCK-immunoreactive entero-endocrine cells in the rat small intestinal mucosa. Acta Anat (Basel) 1996;156:123–131. doi: 10.1159/000147837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan AM, Polak JM, Solcia E, Capella C, Hudson D, Pearse AG. Electron immunohistochemical evidence for the human intestinal I cell as the source of CCK. Gut. 1978;19:403–407. doi: 10.1136/gut.19.5.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dockray GJ. The versatility of the vagus. Physiol Behav. 2009;97:531–536. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth CA, Pritchard DM. Suppression of apoptosis, crypt hyperplasia, and altered differentiation in the colonic epithelia of bak-null mice. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:943–952. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracz AD, Ramalingam S, Magness ST. Sox9 expression marks a subset of CD24-expressing small intestine epithelial stem cells that form organoids in vitro. Am J Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;298:G590–G600. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00470.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaki S, Mitsui R, Hayashi H, Kato I, Sugiya H, Iwanaga T, Furness JB, Kuwahara A. Short-chain fatty acid receptor, GPR43, is expressed by enteroendocrine cells and mucosal mast cells in rat intestine. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;324:353–360. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-0140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizhatil K, Baker SA, Arshavsky VY, Bennett V. Ankyrin-G promotes cyclic nucleotide-gated channel transport to rod photoreceptor sensory cells. Science. 2009;323:1614–1617. doi: 10.1126/science.1169789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacourse KA, Lay JM, Swanberg LJ, Jenkins C, Samuelson LC. Molecular structure of the mouse CCK-A receptor gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;236:630–635. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson LI, Rehfeld JF. Distribution of gastrin and CCK cells in the rat gastrointestinal tract. Evidence for the occurrence of three distinct cell types storing COOH-terminal gastrin immunoreactivity. Histochemistry. 1978;58:23–31. doi: 10.1007/BF00489946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson LI, Goltermann N, de Magistris L, Rehfeld JF, Schwartz TW. Somatostatin cell processes as pathways for paracrine secretion. Science. 1979;205:1393–1395. doi: 10.1126/science.382360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle RA. Cholecystokinin. In: Walsh JH, Dockray GJ, editors. Gut peptides: biochemistry and physiology. Raven; New York: 1994. pp. 175–216. [Google Scholar]

- Liddle RA. Cholecystokinin cells. Annu Rev Physiol. 1997;59:221–242. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg JM, Tatemoto K, Terenius L, Hellstrom PM, Mutt V, Hökfelt T, Hamberger B. Localization of peptide YY (PYY) in gastrointestinal endocrine cells and effects on intestinal blood flow and motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:4471–4475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.14.4471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantyh CR, Pappas TN, Vigna SR. Localization of cholecystokinin A and cholecystokinin B/gastrin receptors in the canine upper gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1019–1030. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida K, Kamizato M, Kawai T, Masuda K, Takeo K, Teshima-Kondo S, Tanahashi T, Rokutan K. Interleukin-18 is a crucial determinant of vulnerability of the mouse rectum to psychosocial stress. FASEB J. 2009;23:1797–1805. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-125005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raybould HE, Meyer JH, Tabrizi Y, Liddle RA, Tso P. Inhibition of gastric emptying in response to intestinal lipid is dependent on chylomicron formation. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:R1834–R1838. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.6.R1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel BS, Shaito A, Motoike T, Rey FE, Backhed F, Manchester JK, Hammer RE, Williams SC, Crowley J, Yanagisawa M, Gordon JI. Effects of the gutmicrobiota on host adiposity are modulated by the short-chain fatty-acid binding G protein-coupled receptor, Gpr41. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:16767–16772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808567105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternini C, Wong H, Pham T, De Giorgio R, Miller LJ, Kuntz SM, Reeve JR, Walsh JH, Raybould HE. Expression of cholecystokinin A receptors in neurons innervating the rat stomach and intestine. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1136–1146. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70399-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson LH, Grealish S, Kirk D, Bjorklund A. Reconstruction of the nigrostriatal dopamine pathway in the adult mouse brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:625–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.