Abstract

1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D) increases intestinal Ca absorption when dietary Ca intake is low by inducing gene expression through the vitamin D receptor (VDR). 1,25(OH)2D-regulated Ca absorption has been studied extensively in the small intestine, but VDR is also present in the large intestine. Our goal was to determine the impact of large intestinal VDR deletion on Ca and bone metabolism. We used transgenic mice expressing Cre-recombinase driven by the 9.5 kb human caudal type homeobox 2 (CDX2) promoter to delete floxed VDR alleles from the caudal region of the mouse (CDX2-KO). Weanling CDX2-KO mice and control littermates were fed low (0.25%) or normal (0.5%) Ca diets for 7 weeks. Serum and urinary Ca, vitamin D metabolites, bone parameters, and gene expression were analyzed. Loss of the VDR in CDX2-KO was confirmed in colon and kidney. Unexpectedly, CDX2-KO had lower serum PTH (−65% of controls, p<0.001) but normal serum 1,25(OH)2D and Ca levels. Despite elevated urinary Ca loss (8-fold higher in CDX2-KO) and reduced colonic TRPV6 (−90%) and CaBPD9k (−80%) mRNA levels, CDX2-KO mice had only modestly lower femoral bone density. Interestingly, duodenal TRPV6 and CaBPD9k mRNA expression was 4- and 3-fold higher, respectively, and there was a trend towards increased duodenal Ca absorption (+19%, p=0.076) in the CDX2-KO mice. The major finding of this study is that large intestine VDR significantly contributes to whole body Ca metabolism but that duodenal compensation may prevent the consequences of VDR deletion from large intestine and kidney in growing mice.

Keywords: Vitamin D, Vitamin D receptor, Ca metabolism, Large intestine, CDX2P9.5

Introduction

Whole body calcium (Ca) metabolism is regulated by a multi-tissue axis whose coordinated actions serve to maintain serum Ca levels within a narrow range.(1) Among these organs is the intestine, where Ca absorption from the diet is essential for maintaining Ca balance and bone health.(2,3) To protect bone during periods of habitual low dietary Ca intake, a physiological adaptive response occurs that increases secretion of PTH, activates the expression of renal CYP27B1, and enhances conversion of 25 hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) into 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)2D). 1,25(OH)2D increases renal Ca reabsorption, bone resorption and intestinal Ca absorption efficiency by binding to the vitamin D receptor (VDR) and activating transcription of target genes.(4) Thus, under conditions of dietary Ca restriction 1,25(OH)2D becomes critical for maintaining whole body Ca metabolism.

The proximal small intestine has traditionally been viewed as the most important site for 1,25(OH)2D-regulated active Ca absorption.(5) However, we have previously shown that the VDR is expressed throughout the whole intestine with the highest levels observed in cecum and colon.(2) This suggests that VDR expression in the lower intestine may have a role in normal Ca homeostasis. Consistent with this hypothesis, we and others have shown that in VDR knockout mice (VDRKO), intestinal Ca absorption efficiency is significantly reduced(6,7) and accompanied by reduced expression of the 1,25(OH)2D-target genes TRPV6 and CaBPD9k in duodenum and colon.(2) In addition, while villin promoter-mediated transgenic expression of VDR in the entire intestine was sufficient to normalize Ca absorption efficiency and prevent rickets in VDRKO mice, transgenic expression of VDR in just the proximal small intestine of VDRKO mice using the adenosine deaminase (ADA) promoter was insufficient.(8) These findings suggest that VDR expression in the lower bowel contributes significantly to net Ca absorption. Others have previously used Ussing chambers to show that vitamin D-regulated Ca absorption exists in the large intestine(9,10) and various probiotics have been reported to enhance Ca absorption in the lower bowel.(11,12) However the relative importance of 1,25(OH)2D-mediated regulation of Ca absorption in the large intestine to whole body Ca and bone metabolism during growth has not been carefully studied. We hypothesize that VDR in the lower bowel plays a critical role in the regulation of whole body Ca homeostasis. To test our hypothesis, we generated a mouse model lacking VDR in distal ileum, cecum and colon and then examined the consequences of this deletion on whole body Ca and bone metabolism.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Mice containing loxP sites flanking exon 2 of the VDR gene (VDRflox/flox, genetic background C57BL/6 x TT2) were a gift from Dr. S. Kato (University of Tokyo, Japan).(13) The Rosa26Rflox/flox mice (B6.129S4-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1Sor/J; The Jackson Laborary, Bar Harbor, ME) contain a lox-STOP-lox sequence upstream from the E. coli β-galactosidase gene (βgal).(14) CDX2-Cre+/− mice (B6.Cg-Tg (CDX2-Cre)101Erf/J; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) possess a 9.5-kb fragment of the human CDX2 gene promoter and upstream flanking elements (CDX2P9.5).(15) The CDX2P9.5 fragment is broadly expressed throughout the caudal region of the embryo during early development, with tightly restricted transgene expression in the terminal ileum, cecum and colon in adult tissues.(15)

Experimental Design

Rosa26Rflox/flox mice were crossed with VDRflox/flox mice to generate VDRflox/flox;Rosa26Rflox/flox mice. To delete VDR we crossed the VDRflox/flox;Rosa26Rflox/flox with the CDX2-Cre+/− mice to generate triple transgenic experimental mice VDRflox/flox;Rosa26Rflox/flox;CDX2-Cre+/− (CDX2-KO). Mice from these litters lacking the CDX2-Cre transgene (VDRflox/flox;Rosa26Rflox/flox) were used as controls. CDX2-KO and control mice were randomly assigned to AIN93G diets (1000 IU vitamin D3/kg diet, 0.4% P, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) with either normal Ca (0.5%) or low Ca (0.25%) from weaning until 10 weeks of age (n = 5–7 males and 5–7 females per group). Food and water were provided ad libitum. Mice were individually-housed on TEK-fresh bedding (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) in ventilated isolator caging systems at the Purdue University Animal Facilities and maintained in an UVB light-free environment on a 12 h-light/dark cycle under standard conditions of temperature and humidity. Mice were deprived of food 12 h prior to sacrifice. The day of the study, mice were anesthetized with a ketamine (22 mg/mL):xylazine (33 mg/mL) injection (0.1 mL/20 g body weight)). Mice were euthanized by exsanguination under anesthesia. Blood samples, tissue for gene expression, and femora were collected for analysis. A different set of mice (n= 6–7 males and 6–7 females per genotype) was used to examine Ca absorption in vivo and duodenal protein levels. Finally a third group of mice (n=2–3 females and 2–3 males per genotype) was used to examine tissues for βgal enzymatic activity. All experimental results represent the data collected from individual mice. The sample size for each treatment group was calculated using variance estimates from our published data and α = 0.05 and β=0.8. Our analysis indicated that with n=12 mice per group we could detect a 30% difference between groups for Ca absorption and with n=8 mice we could observe the same difference in gene expression across our groups. All the samples for analysis were processed by block randomization and investigators assessing the experimental outcomes were blinded to the genotype and dietary treatment. All of the experiments were approved by the Purdue University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Mouse genotyping

Genomic DNA for genotyping was isolated from toe clips and prepared by using standard protocols.(16) Animals were genotyped for the Cre gene, the floxed VDR gene, and the ROSA26R allele using conditions and primers that we previously reported.(17,18)

Serum and Urine Analysis

Serum and urinary Ca, phosphate (Pi) and creatinine concentrations were measured using the QuantiChrom™ Ca, phosphate, and creatinine assay kits (BioAssay Systems, Hayward, CA). Serum 1,25(OH)2D was measured by radioimmunoassay (ImmunoDiagnostic Systems, Fountain Hills, AZ),(2) and intact PTH was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Immunotopics Inc., San Clemente, CA).

Gene expression

At harvest, mucosal scrapings of duodenum and colon, and minced kidneys were immediately frozen in TriReagent (Molecular Research Center Inc., Cincinnati, OH). The duodenum was the 2 cm segment starting 0.5 cm after the pyloric sphincter; the proximal colon was the 2 cm segment 0.5 cm from the cecum and distal colon was the 2 cm segment 0.5 cm from the rectum. RNA from intestine and kidney was isolated according to the manufacturer’s directions. The isolated RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA(19) and RT-PCR was conducted using primers and PCR conditions as previously reported: RPLP0(19), TRPV6, CaBPD9k(4) TRPV5, CaBPD28k(19), CYP27B1(20), CYP24A1(21), VDR(20) CLDN2(22), CLDN12(23) and Ca sensing receptor (CaSR)(24). ZO-1 mRNA was determined by using the primers ZO-1 #1: 5’TCAGCAGCTAAGGAAGAGTGG’3 and ZO-1 #2: 5’CATTATCAGACACCGGCTCA’3.

Confirmation of VDR deletion

For the detection of the VDR mRNA with a floxed or recombined exon 2 allele in cDNA from CDX2-KO mice tissues, we used the primers #1: 5’TCTGTGAGTCTTCCCAGGAG3’ and #2: 5’ACTCCTTCATCATGCCAATGT3’ and the RT-PCR cycling conditions: 95°C/3 min (1 cycle), 95°C/30s, 59°C/30s, 72°C/2 min (40 cycles). This resulted in a 355 bp PCR product for the transcript from the non-recombined floxed VDR allele and a 180 bp band for the transcript from the recombined KO allele. The specificity of VDR deletion was confirmed by demonstrating the lack of allele deletion in pooled cDNA from the duodenum of C57BL/6J mice. As a control for VDR deletion we used pooled duodenal cDNA from global VDRKO mice.

Enzymatic Detection of β-galactosidase Activity in Organs

Tissues to be examined for β-galactosidase (β-gal) enzymatic activity were analyzed as we have previously described.(17)

Bone Imaging

Femur samples were harvested, and prepared for imaging analysis as previously described.(3) Femur length was recorded using a digital caliper (Mitutoyo America Corporation, Aurora, IL). Fixed femurs were analyzed by micro-computed tomography (µCT 40, Scanco Medical AG, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) using our published methods.(3) We obtained images for bone volume fraction (BV/TV), trabecular number (Tb.N), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), trabecular separation (Tb.Sp), total cross-sectional area inside the periosteal envelope (Tt.Ar), cortical area (Ct.Ar), cortical area fraction (Ct.Ar/Tt.Ar), and cortical thickness (Ct.Th).

Ca Absorption

Ca absorption was assessed in a set of mice fed the 0.5% Ca diet with the oral gavage method originally described by Van Cromphaut et al.(7) and used by us elsewhere.(3)

Western Blot Analysis of VDR

Duodenum segments were rinsed in ice cold Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) + 5 mmol/L EGTA (pH 7.42) and mucosal scrapings were prepared as described by Wang et al.(25) Total protein concentration was measured with a Detergent Compatible Protein Assay (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and Western Blot analysis was conducted as described elsewhere.(26) Samples from individual mice and a pooled tissue sample for each genotype were analyzed. Briefly, 30 µg of protein were separated onto a 12.5% Tris-HCL precast Gel (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules CA) and transferred onto a 0.45 µm PVDF membrane (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). For the primary antibodies the membrane was incubated with anti-VDR (1:500 dilution, D-6 Santa Cruz Biotech, Dallas, TX)(25), or anti-βactin (1:1000 dilution, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The membrane was then incubated with the HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG light chain, secondary antibody (1:5000 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA). The HRP signal was detected with the ECL Super Signal system (ThermoScientific, Rockford, IL). The relative band densities were analyzed using Image J 1.48v software (NIH).

Statistical Analysis

Main effects (dietary Ca, genotype) and their interaction were analyzed by ANCOVA with gender as a covariate using SAS enterprise 4.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Extreme values were identified using a z-score with a 2.5% cut off in either tail of the distribution of groups. If data were not normally distributed, the BOXCOX assessment was performed and data were transformed: Ca absorption and Tb.Th (1/y); distal colon (CoD), TRPV6 mRNA, proximal colon (CoP) CaBPD9k mRNA, and duodenum (Dd) CYP24A1 mRNA (y0.5); Kidney (Kd) CYP24A1 mRNA (1/y)0.25; body weight (1/y)2; Ca/creatinine urinary ratio, serum PTH, Dd and CoP TRPV6 mRNA, Dd CaSR mRNA, Kd, Dd, and CoD CaBPD9k mRNA, Kd CaBPD28k mRNA, CoP CYP24A mRNA, Dd CLDN2 mRNA, Dd and CoD ZO-1 mRNA, CoP and CoD CLDN12 mRNA, BV/TV, Tb.N, and Tt.Ar (natural log). Differences were considered significant when p<0.05. Data are expressed as ANCOVA adjusted least square means (LSmean) ± SEM. The Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test was used to determine differences among LSmeans.

Results

VDR gene deletion in CDX2-KO mice

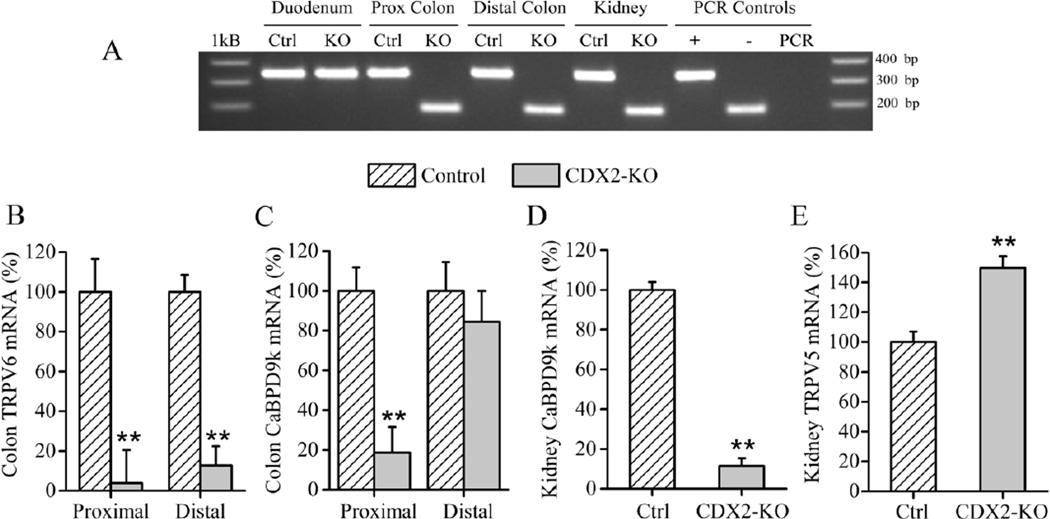

In adult CDX2-Cre mice Cre activity is limited to the distal intestine. However, during embryonic development, the CDX2-Cre transgene is transiently expressed in the tail bud and caudal part of the neural tube (i.e. lower half of the embryo), affecting other organs in addition to the large intestine including: kidney, spleen, thymus, and skin and muscle in the lower half of the body.(15) Recombination of floxed alleles during this period persist into adulthood. Consistent with these earlier findings, gross β-gal expression in the intestine was limited to the terminal ileum, cecum and colon. However, we also saw gross β-gal expression in the kidney, spleen and muscle from the lower part of the body (Suppl. Fig. 1). RT-PCR of colonic and renal cDNA from CDX2-KO mice generated amplicons for the exon 2 deleted-VDR transcript while control tissues and duodenal cDNA from CDX2-KO mice expressed the larger 355 bp amplicon of the intact VDR mRNA (Fig. 1A). Inactivation of the VDR gene in the colon of the CDX2-KO mice was reflected in the lower mRNA expression of the two classical 1,25(OH)2D-target genes TRPV6 and CaBPD9k. TRPV6 mRNA was reduced by >90% (p<0.001) in the proximal colon and >85% (p<0.001) in the distal colon (Fig. 1B). In contrast, while CaBPD9k mRNA was >80% lower (p<0.001) in the proximal colon of CDX2-KO, CaBPD9k expression was not different in the distal colon (Fig. 1C). Consistent with the recombination of the floxed VDR allele in the kidney, CDX2-KO mice had low renal CaBPD9k mRNA levels (−88% of control, p<0.001) and high TRPV5 (+50% of control, p<0.001) (Fig. 1D, E) with no change in CaBPD28k (data not shown). These results are similar to what has been previously reported for the global VDRKO mouse.(2,6)

Fig. 1. Confirmation of VDR deletion in CDX2-KO mice.

(A) Measurement of mRNA from full length and knockout VDR alleles by RT-PCR; CDX2-KO mice (KO), VDRf/f mice (Ctrl); KO allele transcript = 180 bp; floxed allele transcript = 350 bp; (+) = cDNA from C57BL/6J mice; (−) = cDNA from global VDRKO mice; PCR= PCR sample lacking cDNA, 1Kb = 1Kb DNA ladder. (B–E) mRNA level of 1,25(OH)2D target genes in colon: (B) TRPV6 and (C) CaBPD9k, or kidney (D) CaBPD9k and (E) TRPV5. Bars represent the LSmean±SEM (n=20–24 per genotype) expressed as (%) relative to control. Different from control at **p<0.01.

Gross appearance and serum phenotype

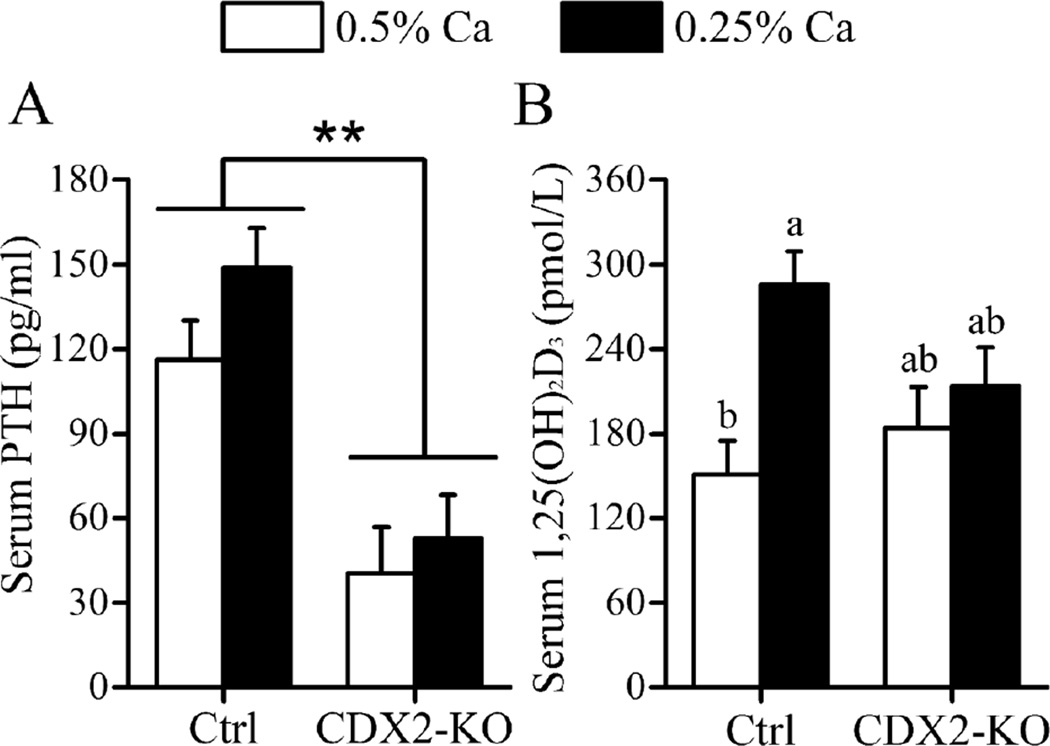

Control and CDX2-KO mice were healthy throughout the study. Consistent with VDR recombination in the caudal part of the mouse, CDX2-KO mice developed alopecia in the lower half of the body. CDX2-KO mice were slightly but significantly smaller than the controls (−7% vs. control, p=0.005) (Table 1). Regardless of genotype, fasting serum PTH increased in response to the low Ca diet (+29% vs. 0.5% Ca diet, p=0.048). However, serum PTH was 65% lower in CDX2-KO (p<0.001) compared to control mice (Fig. 2A). Despite the lower PTH serum levels in CDX2-KO, serum 1,25(OH)2D (198.9 ± 20.1 vs. control, 218.2 ± 17.7 pmol/L), serum Ca (2.81 ± 0.07 vs. control, 2.72 ± 0.06 mmol/L), and serum phosphate levels (1.8 ± 0.07 vs. control, 1.86 ± 0.07 mmol/L) were not different from controls. A trend for a significant genotype-by-diet interaction was detected for serum 1,25(OH)2D (p=0.057) as well as a significant diet effect (0.25% > 0.5% Ca diet, p=0.004). However, while serum 1,25(OH)2D was elevated by the low Ca diet in control mice (p=0.003) this did not occur in CDX2-KO mice (p=0.88) (Fig. 2B).

Table 1.

µCT measurements of femoral midshaft and distal metaphysis in 10-week-old CDX2-KO and control mice fed with 0.5% (normal) or 0.25% (low) Ca diets.1

| Control | CDX2-KO | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5% Ca | 0.25% Ca | 0.5% Ca | 0.25% Ca | |

| Body weight (g)* | 22.1 ± 0.5 (12)b,3 | 21.5 ± 0.5 (13)ab | 20.32 ± 0.57 (10)ab | 20.2 ± 0.57 (10)a |

| Bone | ||||

| Femur Length (mm)** | 15.4 ± 0.1 (12)b | 15.2 ± 0.1 (13)ab | 15 ± 0.1 (10)ab | 14.9 ± 0.1 (10)a |

| BV/TV2 | 0.029 ± 0.003 (12)a | 0.025 ± 0.003 (13)a | 0.03 ± 0.003 (10)a | 0.03 ± 0.003 (10)a |

| Tb.Th (mm)Ɨ | 0.043 ± 0.001 (12)a | 0.043 ± 0.001 (13)a | 0.041 ± 0.001 (10)a | 0.04 ± 0.001 (10)a |

| Tb.N (1/mm)* | 2.72 ± 0.11 (12)a | 2.45 ± 0.11 (13)a | 2.81 ± 0.13 (10)a | 2.85 ± 0.13 (10)a |

| Tb.Sp (mm)* | 0.39 ± 0.02 (12)a | 0.44 ± 0.02 (13)a | 0.38 ± 0.02 (10)a | 0.38 ± 0.02 (10)a |

| Tt.Ar (mm2)** | 1.94 ± 0.025 (12)a | 1.88 ± 0.024 (13)ab | 1.81 ± 0.03 (10)b | 1.84 ± 0.03 (10)ab |

| Ct.Ar (mm2)** | 0.79 ± 0.009 (12)a | 0.75 ± 0.009 (13)b | 0.74 ± 0.01 (10)b | 0.74 ± 0.01 (10)b |

| Ct.Ar/Tt.Ar | 0.41 ± 0.005 (12)a | 0.4 ± 0.005 (13)a | 0.41 ± 0.004 (10)a | 0.4 ± 0.004 (10)a |

| Ct.Th (mm) | 0.181 ± 0.002 (12)a | 0.174 ± 0.002 (13)b | 0.176 ± 0.002 (10)ab | 0.1743 ± 0.002 (10)ab |

Statistical analyses were performed using ANCOVA with gender as covariate.

Bone volume fraction (BV/TV); trabecular thickness (Tb.Th); trabecular number (Tb.N) and trabecular separation (Tb.Sp); total cross-sectional area inside the periosteal envelope (Tt.Ar); cortical bone area (Ct.Ar); cortical area fraction (Ct.Ar/Tt.Ar) and cortical thickness (Ct.Th).

Data are expressed as LSmean ± SEM (n),

Genotype main effects were noted with superscripts next to the phenotype name **p<0.01, *p<0.05, P<0.1Ɨ.

For each phenotype, groups with different letter superscripts are statistically different, (Tukey–Kramer test, p<0.05).

Fig. 2. CDX2-KO Mice Have Normal Serum 1,25(OH)2D But Low Serum PTH Levels.

Serum levels of (A) PTH and (B) 1,25(OH)2D in control, VDRf/f (Ctrl) and CDX2-KO mice fed 0.25% or 0.5% Ca diets. Bars represent the LSmean±SEM (n=10–12 mice/diet/genotype). **Different from control at p<0.01. Groups with different letter superscripts are statistically different (Tukey-Kramer test, p<0.05).

Renal phenotype

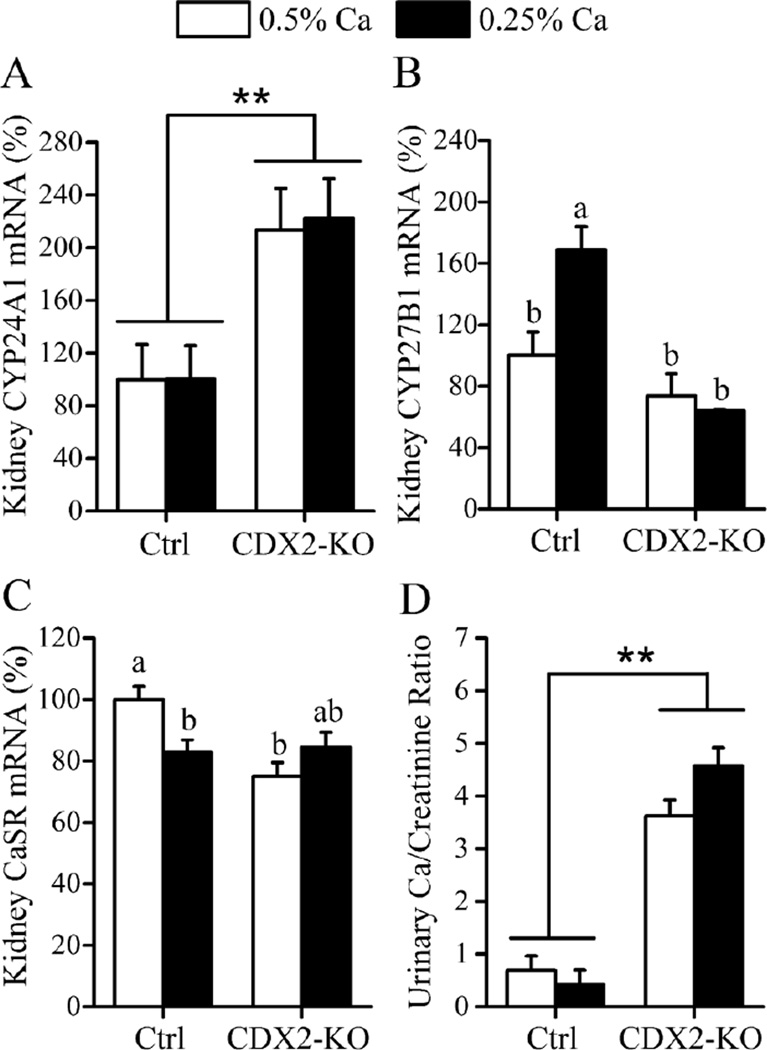

The renal enzymes CYP27B1 and CYP24A1 control the renal production of 1,25(OH)2D and influence serum 1,25(OH)2D levels. Despite the fact that serum 1,25(OH)2D levels were not different between genotypes (Fig. 2B), CYP24A1 mRNA was 2-fold higher in CDX2-KO (p<0.001) compared with controls (Fig. 3A). Similar to what we observed for serum 1,25(OH)2D levels, renal CYP27B1 mRNA levels were elevated by dietary Ca restriction in control, but not CDX2-KO mice (Fig. 3B) reflecting a significant genotype-by-diet interaction on the renal CYP27B1 mRNA (p=0.013). Renal CaSR gene expression was also affected by a genotype main effect (control > CDX2-KO, p=0.014) and by a significant genotype-by-diet interaction (p=0.005). While renal CaSR mRNA was reduced in control mice fed the low Ca diet (−17 % vs. 0.5% Ca diet, p=0.032) no diet effect was observed in the CDX2-KO mice (Fig. 3C). Urinary Ca was markedly and significantly higher than controls in CDX2-KO mice (8-fold higher urinary Ca/creatinine ratio, p<0.001, Fig. 3D) but urinary phosphate levels were not affected by VDR deletion (16.3 ± 2 vs. control 16.5 ± 1.9 Pi/creatinine ratio).

Fig. 3. Renal phenotype of CDX2-KO mice.

(A) CYP24A1, (B) CYP27B1 and (C) CaSR renal mRNA levels in control, VDRf/f (Ctrl) and CDX2-KO mice fed 0.25% or 0.5% Ca diets. Data are expressed as (%) relative to controls on the 0.5% Ca diet. (D) Urinary Ca/creatinine ratio. Bars reflect the LSmean±SEM (n=10–12 mice/diet/genotype). Different from control at **p<0.01, *p<0.05. Groups with different letter superscripts are statistically different (Tukey–Kramer test, p<0.05).

Bone phenotype

The femora of the CDX2-KO were slightly shorter than control mice (−2.6% vs. control, p=0.007, Table 1). After covariate correction for gender, femoral BV/TV, Ct.Ar/Tt.Ar, and Ct.Th were not different between genotypes. However Ct.Ar and Tt.Ar were lower in the CDX2-KO (−3.8% and −4.2% of controls respectively, p<0.01) while Tb.Th showed a trend towards decreasing in the CDX2-KO (−4.5% vs control, p=0.055). On the other hand, Tb.N was 8% higher (p=0.047) and Tb.Sp smaller (−9.5% vs control, p=0.030) in the CDX2-KO mice compared with controls (Table 1).

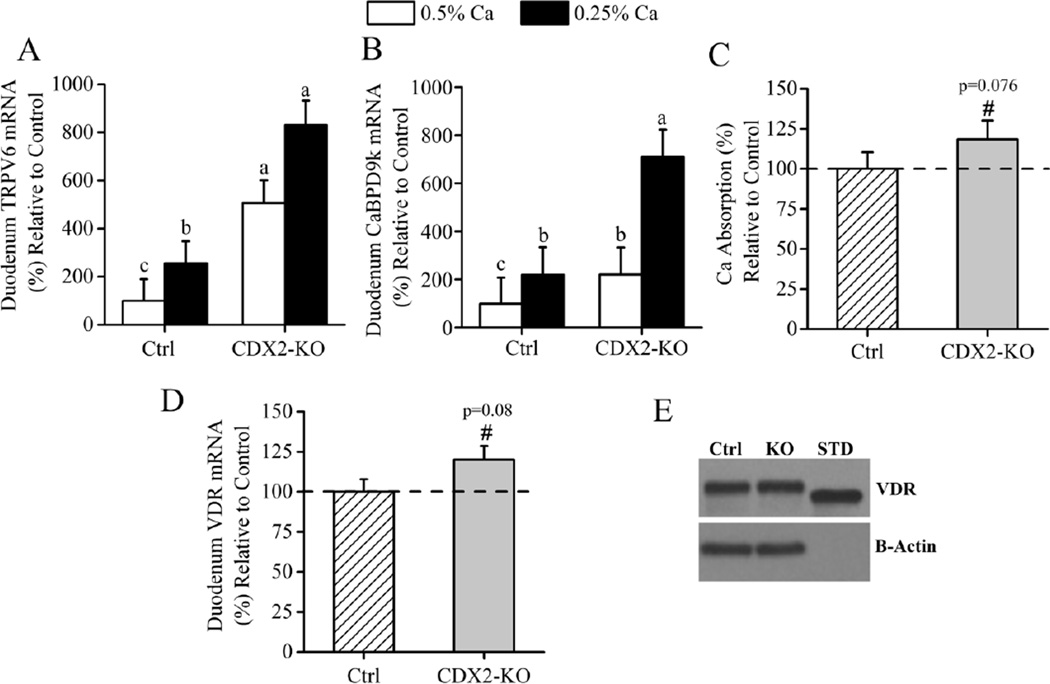

Duodenal response to CDX2-Cre mediated VDR deletion in the distal intestine

In contrast to the colon, duodenal TRPV6 and CaBPD9k mRNA levels were 4- and 3-fold higher respectively, in CDX2-KO compared to control mice (p<0.001). Regardless of genotype, duodenal TRPV6 (p=0.002) and CaBPD9k (p<0.001) gene expression significantly increased in response to dietary Ca restriction (Fig. 4A, B). In CDX2-KO mice on the 0.25% Ca diet, duodenal CaBPD9k mRNA was significantly elevated (p=0.013). We observed a trend for higher Ca absorption (+19%, p=0.076) in the CDX2-KO mice fed the 0.5% Ca diet (Fig. 4C). Since the CDX2-KO mice express the intact VDR allele in the duodenum and the duodenal expression of 1,25(OH)2D-target genes was elevated in these mice, we analyzed whether the VDR mRNA and protein levels were increased in the duodenum of CDX2-KO mice. There was a trend towards higher duodenal VDR mRNA levels in the CDX2-KO (p=0.08, Fig. 4D) but VDR protein levels were not significantly different between genotypes (Fig. 4E). To test whether colonic VDR deletion increased local vitamin D metabolism in the intestine we analyzed CYP27B1 and CYP24A1 mRNA levels in duodenum and colon. In control mice fed the 0.5% Ca diet, the intestinal level of these mRNAs were < 4% and < 0.04% of the kidney levels, respectively (p<0.001). CYP27B1 mRNA levels were not affected by genotype in duodenum or distal colon but were lower in the proximal colon CDX2-KO mice (68% of control, p=0.022) (Suppl. Fig.2) CYP24A1 mRNA levels were virtually undetected in the distal colon of both genotype groups, were lower in proximal colon (0.02 ±2.4 vs 8.5±2, p=0.004), and were higher in duodenum of CDX2 KO compared to controls (3.7 ± 0.62 vs. 0.73 ± 0.55, p=0.002).

Fig. 4. Duodenal phenotype of the CDX2-KO mice.

Duodenal (A) TRPV6 and (B) CaBPD9k mRNA in control, VDRf/f (Ctrl) and CDX2-KO mice fed 0.25% or 0.5% Ca diets. Bars reflect the LSmean±SEM (n=10–12 mice/diet/genotype), expressed as (%) relative to controls on the 0.5% Ca diet. Groups with different letter superscripts are statistically different (Tukey–Kramer test, p<0.05). (C) Ca absorption assessed by oral gavage in mice fed the 0.5% Ca diet (n=12–14 mice per genotype). (D) VDR mRNA. Bars reflect the LSmean±SEM (n=20–24 mice per genotype). Data is expressed as (%) relative to controls. Different from control at #p<0.1. (E) Western blot analysis of VDR on pooled duodenal sample from each genotype (Ctrl= control, KO= CDX2-KO, STD= VDR Standard).

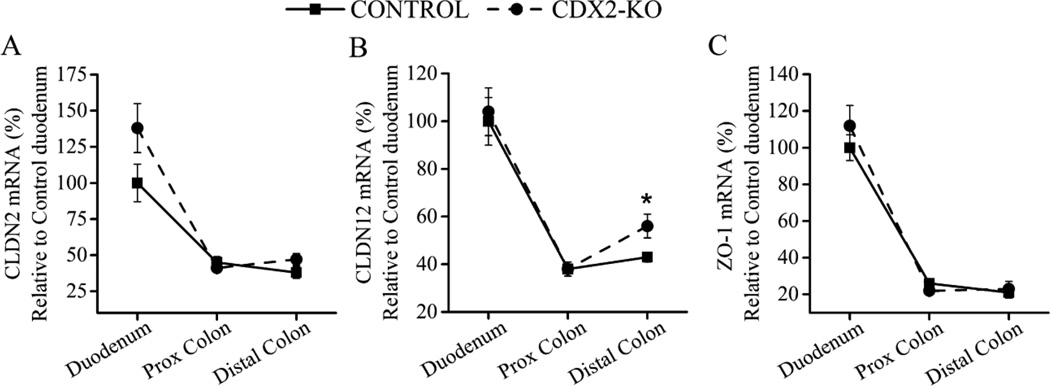

In addition to TRPV6 and CaBPD9k, other proteins have been proposed to influence intestinal Ca absorption.(23,27,28) Duodenal CaSR mRNA expression was very low in both CDX2-KO and control mice and was not affected by genotype (p=0.35) or dietary Ca level (p=0.67) (data not shown). Message levels for proteins proposed to mediate paracellular movement of Ca across the intestinal epithelium, i.e. CLDN2, CLDN12 and ZO-1, were 2–4 times higher in the duodenum than the colon (Fig. 5A, B, C). Regardless of genotype, CLDN2 and CLDN12 mRNA levels were not affected by dietary Ca (data not shown) while ZO-1 mRNA expression in distal colon was lower in the animals fed with the 0.25% Ca diet (−32%, p=0.017). In the colon of CDX2-KO mice, only CLDN12 mRNA levels were altered and only in distal colon (+30% of control, p=0.029, Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5. Characterization of intestinal mRNA expression of 1,25(OH)2D-target genes regulated tight junction function.

(A) CLDN2, (B) CLDN12 and (C) ZO-1 mRNA expression in duodenum, and proximal and distal colon. Each data point represents the normalized LSmean±SEM (n=20–24 mice per genotype) for the specific target gene using duodenum mRNA levels of the control mice as reference. Different from control at *p<0.05.

Discussion

By generating mice that lack VDR in the large intestine we confirmed a direct role of 1,25(OH)2D and VDR for the regulation of whole body Ca homeostasis in this segment. However, our findings are not as straightforward as we original hypothesized. Based on our earlier data we expected that the deletion of VDR from the lower bowel would lead to a phenotype similar to the global VDRKO mouse, i.e. growth suppression, hypocalcemia and osteomalacia caused by reduced intestinal Ca absorption.(6) While the CDX2-KO mice had normal serum Ca and normal femoral trabecular bone microarchitecture, the femora of CDX2-KO mice was slightly smaller than controls and exhibited modest but significant reductions in cortical bone parameters. Although this phenotype is less extreme than the global VDRKO mice, there was clear evidence that Ca metabolism was disturbed in these mice.

A surprising aspect of our study is that the serum hormonal profile of CDX2-KO mice was abnormal. Contrary to our expectation, serum PTH was significantly lower in CDX2-KO than in controls (Fig. 2A). PTH is a well-established inducer of the CYP27B1 enzymatic activity(29,30) and can reduce the stability of CYP24A1 mRNA(31) thereby accounting for the low CYP27B1 and high CYP24A1 mRNA expression observed in kidneys from CDX2-KO mice (Fig. 3A). Renal CYP27B1 and the CYP24A1 are very tightly and reciprocally regulated by 1,25(OH)2D and PTH.(32) Yet, despite the low serum PTH, the low CYP27B1 mRNA levels, and the elevated CYP24A1 mRNA levels in the CDX2-KO mice, serum 1,25(OH)2D in these animals was normal. The elevated renal CYP24A1 mRNA levels observed in the CDX2-KO mice could be reflected in elevation of the vitamin D catabolites 1,24,25-(OH)3D and 24,25-(OH)2D in serum. While 1,24,25(OH)3D is a product resulting from the 24 hydroxylation of 1,25(OH)2D(33) and much less active than 1,25(OH)2D;(34) 24,25(OH)2D is a stable metabolite and has been reported to stimulate the differentiation and maturation of growth plate chondrocytes,(35) and fracture healing.(36,37) Bone length is determined by the production and proliferation of chondrocytes.(38) Thus, a beneficial effect from the elevated 24,25-(OH)2D levels should be reflected in the bone length of the CDX2-KO mice. However, these mice exhibited modest but significant reductions in femur length compared to controls. This is inconsistent with the proposed anabolic effects of 24,25-(OH)2D and suggests that its levels do not account for our findings in the CDX2-KO mice.

Another abnormal feature of the hormone profile was revealed during dietary Ca restriction – neither serum PTH nor 1,25(OH)2D levels increased on the low Ca diet in CDX2-KO mice. Normally during diet induced hypocalcemia, increased serum PTH inactivates renal CaSR,(39,40) induces CYP27B1 expression, and inhibits CYP24A1 activity in the kidney.(41) This allows for increased renal production and secretion of 1,25(OH)2D, and its elevation in serum.(42) Although we showed that low Ca diet moderately increased serum PTH, decreased renal CaSR transcript levels, increased renal CYP27B1 mRNA, and elevated serum 1,25(OH)2D levels in the control animals, this adaptive response was lost in the CDX2-KO.

One of the limitations of the CDX2-KO mouse is that Cre-mediated deletion of floxed alleles occurs in the caudal region of the mouse during embryonic development.(15) As a result, the deletion of VDR was not restricted to the large intestine but extended to other tissues. Even though we did not assess the parathyroid gland for Cre-recombinase activity in our animal model it is unlikely that the VDR is deleted in this tissue because our serum profile is not consistent with data from parathyroid gland-specific VDR knockout mice who have elevated serum PTH and 1,25(OH)2D levels, and increased bone resorption.(43)

Compared to the controls, the CDX2-KO mice had shorter femurs and thinner cortices reflected by the lower Ct.Ar and Tt.Ar measured at midshaft. These geometric parameters are useful predictors of bone strength and mechanical properties.(44,45) During growth the diameter of bones increase, which increases their strength.(45) Consequently, the slight decrease in bone geometry may result in reduced strength in the CDX2-KO mice compared to controls. On the other hand, while we observed a trend towards a lower Tb.Th, Tb.N was higher and Tb.Sp was lower in the CDX2-KO mice (Table 1). Our results suggest that the bones of these animals suffered the consequences of disturbed Ca metabolism due to VDR deletion. However, the extent of the bone loss observed seem to be very modest compared to what we expected. We propose that in the CDX2-KO mice a compensatory increase in Ca absorption in the small intestine may be in place allowing them to protect their bones to some degree. Supporting this hypothesis others have provided evidence for adaptive responses to maintain intestinal Ca homeostasis when the function of an intestinal segment is impaired. Jongwattanapisan et al.(46) demonstrated that in rats the cecum is an important site for Ca absorption and the absence of its function leads to disturbed Ca homeostasis, reduced BMD and BMC in femur and spine, and compensatory increase in active colonic Ca absorption. Furthermore, Shiga et al.(47) showed that in cecocolonectomized rats, apparent Ca absorption, estimated by balance, significantly increased compared with sham-operated rats (p=0.02) suggesting a compensatory increase in the capacity of the small intestine to absorb Ca following lower bowel resection. In our experiment we observed similar outcomes and we will discuss them in the following section.

We found evidence that small intestinal Ca absorption compensates for the loss of VDR in the lower intestine of CDX2-KO mice. We previously reported that 1,25(OH)2D-induced changes in TRPV6 and CaBPD9k mRNA levels precede increases in intestinal Ca absorption(4) and that their levels are positively correlated with Ca absorption efficiency.(3) As expected, in control mice duodenal TRPV6 and CaBPD9k mRNA levels were upregulated in response to the higher serum 1,25(OH)2D induced by the low Ca diet. However, even though CDX2-KO mice had normal serum 1,25(OH)2D levels on the 0.5% Ca diet, duodenal TRPV6 and CaBPD9k transcript levels were 3–4 fold higher than control levels. This suggests that the sensitivity of the small intestine to 1,25(OH)2D was increased as a means to compensate for the loss of VDR in the lower intestine. In addition, despite the fact that serum 1,25(OH)2D levels were not increased by dietary Ca restriction in CDX2-KO mice, TRPV6 and CaBPD9k expression were significantly increased by dietary Ca restriction in both genotypes and the magnitude of this was not different between genotypes. This indicates that in the CDX2-KO mice the intestinal adaptation to low dietary Ca observed may be independent of circulating 1,25(OH)2D.

Although we previously reported that modest changes in VDR levels can alter the sensitivity of enterocytes to 1,25(OH)2D,(21,48) the effects we saw on duodenal TRPV6 and CaBPD9k mRNA levels in CDX2-KO mice were not due to changes in VDR protein levels (Fig. 4E). This indicates that the increased responsiveness is mediated by another mechanism. One such alternative mechanism could be the local, extrarenal synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D by CYP27B1. This hypothesis has been discussed for many years but the physiological importance of CYP27B1 in the intestine, has not yet been demonstrated.(49,50) We examined whether intestinal CYP27B1 mRNA levels were upregulated in CDX2-KO mice, thus increasing the potential for local synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D in these mice. Consistent with our previously published data,(51) we found that CYP27B1 mRNA levels are very low in the intestine compared to renal CYP27B1 mRNA levels (Suppl. Fig. 2). In addition, neither duodenal nor colonic CYP27B1 mRNA levels increased in the CDX2-KO mice. Thus, our data suggest it is unlikely that local formation of calcitriol in the CDX2-KO mice accounts for our observations.

Garg and Mahalle(28) recently proposed the “intestinal calcistat” theory to suggest how CaSR could mediate local intestinal adaptation in response to changes in dietary Ca. However, there is no direct evidence for the CaSR as a regulator of intestinal Ca absorption(52) and CaSR mRNA levels in duodenum did not change in the CXD2-KO mice. Thus, the mechanism underlying the increased sensitivity of the small intestine to 1,25(OH)2D in CDX2-KO mice is not yet clear. In the present study we did not study receptor affinity, thus the possibility of enhanced affinity of the VDR for its ligand to explain this phenomenon cannot be excluded.

A complication to the interpretation of our data is that CDX2-Cre driven deletion of VDR is extended to the kidney. The normal physiological response to dietary Ca restriction in the kidney is to reduce urinary Ca excretion(1) through PTH-actions that enhance distal tubular Ca reabsorption.(39) Here we found that regardless of diet, urinary Ca excretion was 8-fold higher in the CDX2-KO compared with controls (Fig. 3D) suggesting a dysregulation in renal Ca reabsorption. Nonetheless, while urinary Ca losses are an important determinant of whole body Ca retention during growth in humans,(53) in rodents urinary Ca losses are not a major contributor to Ca balance.(54,55) As such, the 8-fold increase we observed may not have a dramatic impact on whole body Ca metabolism in CDX2-KO mice. Others have used Ca kinetics studies to show that increased total Ca absorption observed during periods of high dietary Ca intake is reflected as an increase in urinary Ca excretion in humans.(56,57) Similarly, the elevated urinary Ca levels seen in genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rats are due in part to intestinal Ca over-absorption that results from increased intestinal responsiveness to 1,25(OH)2D.(58) As such, the elevated urinary Ca in CDX2-KO mice could be a reflection of higher small intestinal Ca absorption efficiency. Furthermore, elevated intestinal Ca absorption in CDX2-KO mice could also inhibit PTH secretion, thereby providing a potential mechanism to explain the reduced renal Ca reabsorption and increased Ca excretion in these mice.

One of the weaknesses of this study is that we did not directly measure Ca absorption in the lower intestine. Thus, future studies should focus on determining whether Ca absorption in the lower bowel can be stimulated to improve Ca balance without hypercalcemia. Another limitation of our animal model is that the deletion of the VDR was not restricted to the large intestine. Nevertheless, we were able to characterize the consequences of the lack of VDR from large intestine and kidney highlighting the importance of the VDR in these organs. Our findings are consistent with those from Christakos et al.(59) who used the 9.5kb CDX2 promoter to drive transgenic expression of human VDR exclusively in the large intestine (ileum, cecum and colon) of adult mice. When they crossed the CDX2-hVDR mouse to global VDRKO mice, the presence of VDR in the lower bowel was sufficient to prevent the hypocalcemia, bone defects, and high PTH levels observed in the VDRKO mice. Thus, combined with our current data, there is strong evidence that 1,25(OH)2D-mediated Ca absorption in the lower bowel is important for normal bone growth and mineralization.

In summary, our data support the hypothesis that large intestine VDR significantly contributes to whole body Ca metabolism, and that compensatory mechanisms exist that can minimize the negative impact of large intestine VDR deletion on bone in growing mice (e.g. upregulation of Ca absorption in the small intestine). Our observations could be relevant for two human clinical populations in whom intestinal Ca absorption has been compromised: those that have undergone intestinal resection(60) and those who have undergone gastric bypass.(61) In these patients, enhancing vitamin D-mediated Ca absorption in the distal intestine might serve as a strategy to improve whole body Ca metabolism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mr. John Replogle and Mr. Jeff Rytlewski for their technical assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant DK540111 to JCF. CONACyT, Mexico provided a partial graduate scholarship to PRF.

Footnotes

Disclosures: All authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ roles: Study design: JCF. Study conduct: PRF. Data collection: PRF. Data analysis: PRF. Data interpretation: JCF and PRF. Drafting manuscript: PRF. Approving final version of manuscript: JCF and PRF. JCF takes responsibility for the integrity of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Fleet JC. Molecular Regulation of Calcium Metabolism. In: Weaver CM, Heaney RP, editors. Calcium in Human Health. Nutrition and Health. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2006. pp. 163–190. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xue Y, Fleet JC. Intestinal vitamin D receptor is required for normal calcium and bone metabolism in mice. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(4):1317–1312. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Replogle RA, Li Q, Wang L, Zhang M, Fleet JC. Gene-by-Diet Interactions Influence Calcium Absorption and Bone Density in Mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(3):657–665. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song Y, Peng X, Porta A, et al. Calcium transporter 1 and epithelial calcium channel messenger ribonucleic acid are differentially regulated by 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 in the intestine and kidney of mice. Endocrinology. 2003;144(9):3885–3894. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pansu D, Bellaton C, Roche C, Bronner F. Duodenal and ileal calcium absorption in the rat and effects of vitamin D. Am J Physiol. 1983;244(6):G695–G700. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1983.244.6.G695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song Y, Kato S, Fleet JC. Vitamin D Receptor (VDR) Knockout Mice Reveal VDR-Independent Regulation of Intestinal Calcium Absorption and ECaC2 and Calbindin D9k mRNA. J Nutr. 2003;133(2):374–380. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.2.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Cromphaut SJ, Dewerchin M, Hoenderop JG, et al. Duodenal calcium absorption in vitamin D receptor-knockout mice: functional and molecular aspects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(23):13324–13329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231474698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marks HD, Fleet JC, Peleg S. Transgenic expression of the human Vitamin D receptor (hVDR) in the duodenum of VDR-null mice attenuates the age-dependent decline in calcium absorption. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103:513–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hurwitz S, Bar A. Site of vitamin D action in chick intestine. Am J Physiol. 1972;222(3):761–767. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1972.222.3.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jungbluth H, Binswanger U. Unidirectional duodenal and jejunal calcium and phosphorus transport in the rat: effects of dietary phosphorus depletion, ethane-1-hydroxy-1,1-diphosphonate and 1,25 dihydroxycholecalciferol. Res Exp Med (Berl) 1989;189(6):439–449. doi: 10.1007/BF01855011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van den Heuvel EG, Muijs T, Van Dokkum W, Schaafsma G. Lactulose stimulates calcium absorption in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14(7):1211–1216. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.7.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raschka L, Daniel H. Mechanisms underlying the effects of inulin-type fructans on calcium absorption in the large intestine of rats. Bone. 2005;37(5):728–735. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshizawa T, Handa Y, Uematsu Y, et al. Mice lacking the vitamin D receptor exhibit impaired bone formation, uterine hypoplasia and growth retardation after weaning. Nat Genet. 1997;16:391–396. doi: 10.1038/ng0897-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999;21(1):70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hinoi T, Akyol A, Theisen BK, et al. Mouse model of colonic adenoma-carcinoma progression based on somatic Apc inactivation. Cancer Res. 2007;67(20):9721–9730. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maniatis T, Fritsch EF, Sambrook J. A laboratory manual. New York: Cold Spring Harbor; Molecular cloning. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xue Y, Johnson R, DeSmet M, Snyder PW, Fleet JC. Generation of a transgenic mouse for colorectal cancer research with intestinal cre expression limited to the large intestine. Mol Cancer Res. 2010;8(8):1095–1104. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kovalenko PL, Zhang Z, Yu JG, Li Y, Clinton SK, Fleet JC. Dietary vitamin D and vitamin D receptor level modulate epithelial cell proliferation and apoptosis in the prostate. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4(10):1617–1625. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui M, Li Q, Johnson R, Fleet JC. Villin promoter-mediated transgenic expression of TRPV6 increases intestinal calcium absorption in wild-type and VDR knockout mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2012 doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Healy KD, Zella JB, Prahl JM, DeLuca HF. Regulation of the murine renal vitamin D receptor by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and calcium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(17):9733–9737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633774100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song Y, Fleet JC. Intestinal Resistance to 1,25 Dihydroxyvitamin D in Mice Heterozygous for the Vitamin D Receptor Knockout Allele. Endocrinology. 2007;148(3):1396–1402. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kubota H, Chiba H, Takakuwa Y, et al. Retinoid X receptor alpha and retinoic acid receptor gamma mediate expression of genes encoding tight-junction proteins and barrier function in F9 cells during visceral endodermal differentiation. Exp Cell Res. 2001;263(1):163–172. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujita H, Chiba H, Yokozaki H, et al. Differential expression and subcellular localization of claudin-7, -8, -12, -13, and -15 along the mouse intestine. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54(8):933–944. doi: 10.1369/jhc.6A6944.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bustamante M, Hasler U, Leroy V, et al. Calcium-sensing receptor attenuates AVP-induced aquaporin-2 expression via a calmodulin-dependent mechanism. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(1):109–116. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007010092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, Becklund BR, DeLuca HF. Identification of a highly specific and versatile vitamin D receptor antibody. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;494(2):166–177. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fleet JC, Eksir F, Hance KW, Wood RJ. Vitamin D-inducible calcium transport and gene expression in three Caco-2 cell lines. Am J Physiol. 2002;283(3):G618–G625. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00269.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gama L, Baxendale-Cox LM, Breitwieser GE. Ca2+-sensing receptors in intestinal epithelium. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(4 Pt 1):C1168–C1175. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.4.C1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garg MK, Mahalle N. Calcium homeostasis, and clinical or subclinical vitamin D deficiency--can a hypothesis of "intestinal calcistat" explain it all? Medical Hypotheses. 2013;81(2):253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2013.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kremer R, Goltzman D. Parathyroid hormone stimulates mammalian renal 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-1 alpha-hydroxylase in vitro. Endocrinology. 1982;110(1):294–296. doi: 10.1210/endo-110-1-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siegel N, Wongsurawat N, Armbrecht HJ. Parathyroid hormone stimulates dephosphorylation of the renoredoxin component of the 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-1 alpha-hydroxylase from rat renal cortex. J Biol Chem. 1986;261(36):16998–17003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zierold C, Mings JA, DeLuca HF. Parathyroid hormone regulates 25-hydroxyvitamin D(3)-24-hydroxylase mRNA by altering its stability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(24):13572–13576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241516798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanaka Y, DeLuca HF. Measurement of mammalian 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 24R-and 1 alpha-hydroxylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78(1):196–199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.1.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka Y, Castillo L, DeLuca HF. The 24-hydroxylation of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J Biol Chem. 1977;252(4):1421–1424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holick MF, Kleinerb A, Schnoes HK, Kasten PM, Boyle IT, DeLuca HF. 1,24,25-Trihydroxyvitamin-D3 - Metabolite of Vitamin-D3 Effective on Intestine. J Biol Chem. 1973;248(19):6691–6696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boyan BD, Sylvia VL, Dean DD, Del Toro F, Schwartz Z. Differential regulation of growth plate chondrocytes by 1alpha,25-(OH)2D3 and 24R,25-(OH)2D3 involves cell-maturation-specific membrane-receptor-activated phospholipid metabolism. Crit RevOral Biol Med. 2002;13(2):143–154. doi: 10.1177/154411130201300205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seo EG, Norman AW. Three-fold induction of renal 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-24-hydroxylase activity and increased serum 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 levels are correlated with the healing process after chick tibial fracture. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12(4):598–606. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.4.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.St-Arnaud R. CYP24A1-deficient mice as a tool to uncover a biological activity for vitamin D metabolites hydroxylated at position 24. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;121(1–2):254–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kronenberg HM. Developmental regulation of the growth plate. Nature. 2003;423(6937):332–336. doi: 10.1038/nature01657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown EM. Role of the calcium-sensing receptor in extracellular calcium homeostasis. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;27(3):333–343. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riccardi D, Brown EM. Physiology and pathophysiology of the calcium-sensing receptor in the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298(3):F485–F499. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00608.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson PH, O'Loughlin PD, May BK, Morris HA. Determinants of circulating 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 levels: the role of renal synthesis and catabolism of vitamin D. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;89–90(1–5):111–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.03.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anderson PH, O'Loughlin PD, May BK, Morris HA. Modulation of CYP27B1 and CYP24 mRNA expression in bone is independent of circulating 1,25(OH)2D3 levels. Bone. 2005;36(4):654–662. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meir T, Levi R, Lieben L, et al. Deletion of the vitamin D receptor specifically in the parathyroid demonstrates a limited role for the receptor in parathyroid physiology. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;297(5):F1192–F1198. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00360.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bagi CM, Hanson N, Andresen C, et al. The use of micro-CT to evaluate cortical bone geometry and strength in nude rats: correlation with mechanical testing, pQCT and DXA. Bone. 2006;38(1):136–144. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Viguet-Carrin S, Hoppler M, Membrez Scalfo F, et al. Peak bone strength is influenced by calcium intake in growing rats. Bone. 2014;68:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jongwattanapisan P, Suntornsaratoon P, Wongdee K, Dorkkam N, Krishnamra N, Charoenphandhu N. Impaired body calcium metabolism with low bone density and compensatory colonic calcium absorption in cecectomized rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302(7):E852–E863. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00503.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shiga K, Hara H, Suzuki T, Nishimukai M, Konishi A, Aoyama Y. Massive large bowel resection decreases bone strength and magnesium content but not calcium content of the femur in rats. Nutrition. 2001;17(5):397–402. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(01)00516-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shao A, Wood RJ, Fleet JC. Increased vitamin D receptor level enhances 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-mediated gene expression and calcium transport in Caco-2 cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16(4):615–624. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.4.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vanhooke JL, Prahl JM, Kimmel-Jehan C, et al. CYP27B1 null mice with LacZreporter gene display no 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-1alpha-hydroxylase promoter activity in the skin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(1):75–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509734103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adams JS, Hewison M. Extrarenal expression of the 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1-hydroxylase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;523(1):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fleet JC, Gliniak C, Zhang Z, et al. Serum metabolite profiles and target tissue gene expression define the effect of cholecalciferol intake on calcium metabolism in rats and mice. J Nutr. 2008;138(6):1114–1120. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.6.1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kopic S, Geibel JP. Gastric acid, calcium absorption, and their impact on bone health. Physiol Rev. 2013;93(1):189–268. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matkovic V, Ilich JZ, Andon MB, et al. Urinary calcium, sodium, and bone mass of young females. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;62:417–425. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/62.2.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bauer GC, Carlsson A, Lindquist B. A comparative study on the metabolism of Sr90 and Ca45. Acta Physiol Scand. 1955;35(1):56–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1955.tb01264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aubert JP, Bronner F, Richelle LJ. Quantitation of calcium metabolism. Theory. J Clin Invest. 1963;42:885–897. doi: 10.1172/JCI104781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wastney ME, Ng J, Smith D, Martin BR, Peacock M, Weaver CM. Differences in calcium kinetics between adolescent girls and young women. Am J Physiol. 1996;271(1 Pt 2):R208–R216. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.1.R208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Phang JM, Berman M, Finerman GA, Neer RM, Rosenberg LE, Hahn TJ. Dietary perturbation of calcium metabolism in normal man: compartmental analysis. J Clin Invest. 1969;48(1):67–77. doi: 10.1172/JCI105975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Karnauskas AJ, van Leeuwen JP, van den Bemd GJ, et al. Mechanism and function of high vitamin D receptor levels in genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rats. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(3):447–454. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Christakos S, Seth T, Hirsch J, Porta A, Moulas A, Dhawan P. Vitamin D biology revealed through the study of knockout and transgenic mouse models. Annu Rev Nutr. 2013;33:71–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071812-161249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hylander E, Ladefoged K, Jarnum S. Calcium absorption after intestinal resection. The importance of a preserved colon. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1990;25(7):705–710. doi: 10.3109/00365529008997596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Riedt CS, Brolin RE, Sherrell RM, Field MP, Shapses SA. True fractional calcium absorption is decreased after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(11):1940–1948. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.