Abstract

Here we describe the design, E. coli expression and characterization of a simplified, adaptable and functionally transparent single chain 4-α-helix transmembrane protein frame that binds multiple heme and light activatable porphyrins. Such man-made cofactor-binding oxidoreductases, designed from first principles with minimal reference to natural protein sequences, are known as maquettes. This design is an adaptable frame aiming to uncover core engineering principles governing bioenergetic transmembrane electron-transfer function and recapitulate protein archetypes proposed to represent the origins of photosynthesis.

Keywords: Man-made redox proteins, Maquettes, Protein design, Transmembrane Proteins, Oxidoreductase, Light-activation, Intraprotein electron transfer, Photosynthesis, Respiration, Evolution

1. Introduction

Sequence analysis has revealed the surprising result that critical bioenergetic proteins in both respiration and photosynthesis are related to a common ancestral 4 helix, multi-heme transmembrane protein [1]. Such a protein may have been present close to the origin of Mitchellian chemiosmotic mechanisms in the metabolism of early life [2]. One branch of modern descendants of this protein appears as the multi-heme complexes of respiration and the cytochrome b6f complexes of photosynthesis, while another branch appears in bacteriochlorophyll and chlorophyll-containing photosynthetic reaction centers. Indeed, it has been suggested that the origins of photosynthesis lie in elementary transmembrane proteins that mixed both hemes and light-activated tetrapyrroles, not for energy conservation, but for protection from damaging photochemistry [3]. Evolutionary divergence in function followed by sequence duplication and addition of helices to the original transmembrane helical frame led to one of the histidines that now ligates tetrapyrrole heme bL in cytochrome bc1 complex corresponding in position to a histidine ligating a tetrapyrrole in the photosynthetic bacteriochlorophyll special pair; a second His towards the opposite side of the membrane that now ligates heme bH in bc1 correspondingly ligates non-heme iron between QA and QB in reaction centers [1]. This transition in natural history demonstrates that a multi-tetrapyrrole, α-helical bundle transmembrane protein frame can be exploited for diverse bioenergetic purposes. Such a frame offers a highly attractive target for artificial protein design that can be engineered and eventually inserted in vivo to tap into and exploit natural bioenergetic systems for human needs, such as fuel production or medical remediation.

Here we describe the design, E. coli expression and characterization of a simplified, adaptable and functionally transparent 4-α-helix transmembrane protein frame that binds multiple heme and light activatable tetrapyrroles with the intent to recreate and modulate core transmembrane bioenergetic electron-transfer functions. The term “protein maquette” refers to simple and tractable man-made proteins that capture essential functional features of more complex natural counterparts. These man-made protein maquettes sidestep accumulated evolutionary complexity in sequence and structure, enabling them to be highly adaptable in supporting a range of oxidoreductase functions. They bind a wide range of redox-active cofactors, including natural and unnatural tetrapyrroles [4, 5], as well as single-electron FeS clusters [6, 7] and two-electron flavins [8] and quinones [9]. We have established that with modest sequence adjustment, maquettes replicate a diverse range of natural functions from ultrafast photo-activated intra-protein electron transfer [8] to electron-transfer suppression in the promotion of stable heme dioxygen binding and transport [10].

First-principles protein folding design of maquettes began with binary patterning of polar and non-polar amino acids in a near heptad repeat to favor α-helical supporting hydrogen bonds while using hydrophobic forces to drive helical association into a water soluble bundle [11]. Adapting first-principles protein folding for an amphipathic protein that has both water-soluble and hydrophobic membrane spanning domains has met with challenges [12, 13]. These early amphipathic designs anchored tetrapyrroles only in the water-soluble domain and were constructed from separate identical helices. Subsequent designs secured cofactors only within the hydrophobic region, using either a homodimer of helices ligating a single heme [14] or an α-helical homotetramer anchoring two synthetic tetrapyrroles [15]. Here we report important engineering advances from multimeric to single-chain 4-α-helix maquette proteins expressed in E. coli that include binding sites that ligate porphyrins in both the water soluble and transmembrane domains to make an extended electron-transfer chain.

By recreating basic component parts of respiratory and photosynthetic energy conversion in maquettes, we test our practical understanding of the underlying engineering and construction of their natural counterparts. By proceeding from first principles and designing intentionally robust synthetic protein frames, we aim for a range of practical applications, in vitro and in vivo. Examples include the interception and diversion of high or low potential electrons in living cells directly towards production of useful chemicals and fuels (analogous to synthetic biology's goal of redirecting metabolic pathways), and amelioration of genetic or age-related failures in respiratory energy conversion in humans [16].

2. Materials and Methods

Reagent grade chemicals from Sigma-Aldrich were used, unless otherwise noted.

2.1 Maquette 1 preparation by solid phase synthesis

The tetrameric maquette described in Figure 1 was synthesized on a Pioneer continuous flow solid phase synthesizer (Applied Biosystems) using a standard Fmoc/tBu protection strategy on a Fmoc-PEG-PAL-PS resin (Applied Biosystems) at 0.1 mmole scale. The synthesized peptide was purified on a reversed-phase C18 HPLC column (Vydac) using gradients of acetonitrile (Fisher) and water both containing 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). The purity and molecular weight of the peptide was confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Bruker) to be 5,022 Da. The peptides were purified without difficulty with yields comparable to water-soluble peptides of similar length. The purified protein dissolves readily in various detergents and in methanol.

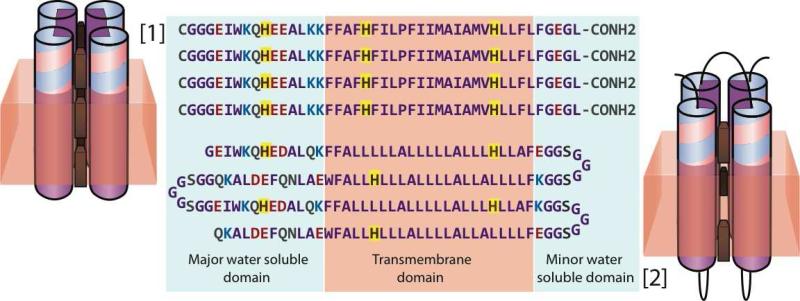

Figure 1.

Sequences and topology of tetramer (1) and single chain (2) designs. Helices are shown as cylinders extending partly out of the membrane (tan) with His anchored tetrapyrrole sites shown in brown. 2 has loops on both sides of the membrane (black) to link helices. Charged amino acids shown in red and blue, and His sites outlined in yellow.

2.2 Maquette 2 preparation by expression in E. coli

2.2.1 Cloning of His tagged KSI-maquette 2 fusion protein

Synthetic DNA with a KpnI restriction enzyme site coding for His-tag, tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage site, and the maquette 2 sequence was obtained from DNA 2.0. Sequence encoding a GGDG loop was added between the His-tag and TEV protease cleavage sites to enhance TEV cleavage efficiency. The gene was cloned into a pET31b(+) vector (Novagen), fusing a Δ5-3-ketosteroidisomerase (KSI) with the maquette 2 to promote the formation of inclusion bodies during protein overexpression. Prior the gene insertion, we made two modifications to the sequence of the pET31b(+) vector. First, a cysteine residue originally present in the pET31b(+) vector between KSI and our cloning site was mutated to glycine to eliminate unwanted disulfide dimers. Second, an AAT codon for asparagine was inserted to the cloning site to adjust the melting temperature of the primers. The cloning and mutagenesis steps were performed by an enzyme free cloning method [17] using a Mastercycler thermal cycler (Eppendorf). Additional details on the PCR reaction conditions and primer designs are presented in the supplementary information. The modified pET31b(+) vector was transformed into DH5α cells using standard transformation protocol. The insertion of correct KSI-maquette 2 sequence into the pET31b(+) vector was confirmed by DNA sequencing using KSI, T7 terminator and T7 promoter primers.

2.2.2 Overexpression and isolation of inclusion bodies

A 125 mL starter culture with 75 mg/L ampicillin was incubated at 37 °C and 225 RPM for 12-16 hours, then transferred into 2 L Terrific Broth containing 75 mg/L ampicillin, and incubated at 37 °C and 225 RPM overnight. The c ells were induced with 2 mM IPTG when the absorbance at 600 nm reached about 0.8. Cells were harvested 4 – 5 hr after induction by centrifugation at 6,000 g for 30 min and stored at −20 °C. The expression was monitored by SDS PAGE as shown in Supplementary Figure S3.

To isolate inclusion bodies, the cell pellets were thawed and resuspended in buffer (50 mM Tris, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM MgSO4, 20 mM CaCl2, 50 mg/L PMSF, 500 mg/L lysozyme, pH 8.0). Triton X-100 was added to a final concentration of 1% and the suspension was stirred at 4 °C for 30 min. DNase I was added to a final concentration of 0.2 g/L and the suspension was stirred at 4 °C for an additional 30 min. The suspension was then subjected to 3 freeze-thaw cycles. 20 min centrifugation at 10,000 g pelleted the inclusion bodies. The detergent resuspension, stirring, and centrifugation steps were repeated two more times to further purify the inclusion bodies. The final pellets containing the inclusion bodies were stored at −80 °C for future use [18]. Supplementary Figure S4 presents an SDS-PAGE gel showing the steps involved in purification of the inclusion bodies. Notably, the overexpressed product present in inclusion bodies before and after solubilization (lanes C and E, respectively) runs at an apparent molecular weight of about 27 kDa. This is significantly less than the 34.2 kDa mass of the designed KSI-2 fusion protein but this discrepancy is typical for incompletely unfolded membrane proteins [19].

2.2.3 Ni-NTA purification of fusion protein

Inclusion bodies were solubilized in denaturing buffer (6 M guanidine-HCl, 100 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris, 2% Tween-20, pH 8.0) in a bath sonicator at 65 °C. The solubilized fusion protein was separated from insoluble debris by centrifugation at 15,000 g for 20min. FPLC purification was performed at rate of 1 mL/min using a 5 mL His-Trap Ni-NTA column (GE Healthcare) affixed to an ACTA Purifier 10 (GE Healthcare). The protein sample was loaded onto the column and washed with 40 mL of denaturing wash buffer (6 M Urea, 100 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris, 2% Tween-20, pH 6.3) followed by 65 mL of urea-free wash buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 2% Tween-20, pH 8.0). A step change to high-imidazole buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, 2% Tween-20, pH 8.0) quickly eluted the fusion protein from the His-Trap Ni-NTA column. FPLC fractions were run on SDS-PAGE to confirm the presence of the fusion protein, shown in Supplementary Figure S5. The apparent molecular weight of the imidazole-eluted protein is about 27 kDa, consistent with the solubilized inclusion body protein seen in the previous gel in Supplementary Figure S4.

To remove excess imidazole and to enable TEV cleavage, the Ni-NTA purified protein was either concentrated using Vivaspin® 20 filter tubes with a 3 kDa cut-off (Sartorius AG) or precipitated using standard ethanol precipitation and lyophilized overnight.

2.2.4 TEV cleavage of fusion protein

To cleave the amphiphilic maquette 2 from the remainder of the fusion protein under non-aggregating conditions, the TEV cleavage reaction must be performed in the presence of detergent(s) and/or denaturant(s); such conditions risk the inactivation of the TEV protease. To address this concern, we tested TEV cleavage activity with a water-soluble maquette construct [5] in the presence of surfactants and denaturants of various concentrations, including Tween-20, Triton X-100, Octylthioglucoside (OTG), sodium cholate, n-Dodecyl β-D-maltoside (DDM), CHAPS, BRIJ35, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and urea. We determined that TEV protease remains active in a combination of 2% Tween-20 and 2 M urea. We solubilized the lyophilized fusion protein in 8% Tween-20 with sonication at 37 °C. U rea and buffer were then added to yield a solution containing 2% Tween-20, 2 M urea, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT. TEV protease was added to this mixture, and the cleavage reaction proceeded overnight at 4 °C. Efficiency of TEV clea vage of the maquette from KSI was confirmed by SDS-PAGE, as shown in Supplementary Figure S6. Cleaved samples were precipitated by 7% trichloroacetic acid. The precipitate was solubilized in 100% hexafluoroacetone (HFA) and purified by reversed-phase HPLC (Waters) on a C4 column (Vydac) with the following solvents: 50:50 water (0.1% TFA): acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) for 20min followed by 100% acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) for 10min and 100% methanol with 50mM HFA. Supplementary Figure S7 illustrates the RP-HPLC timecourse. Purified protein was lyophilized. A small quantity of the dry protein was dissolved in 50:50 acetonitrile:methanol as described in section 2.2.5 and mixed with sinapinic acid for matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS), which confirmed that the molecular weight of the cleaved protein is close to the expected 18,418 Da (Supplementary Figure S8.)

2.2.5 Solubilization of cleaved maquette 2

We have tested solubility of maquette 2 in various detergents including n-dodecylphosphocholine (DPC), DDM, sodium cholate, Zwittergent 3-18, β-octylglucoside, octyl-POE and SDS near or above their CMC (critical micellar concentration). Maquette 2 solubilizes most readily in SDS. 7 mM SDS stock was prepared in 50 mM NaH2PO4, 100 mM NaCl, pH 8.0. Mild sonication at 37 °C was employed to solubilize the protein. Dissolved protein was diluted in buffer to keep the SDS concentration at 3 mM (above its CMC of 1.8 mM) for circular dichroism and cofactor binding characterization.

Since SDS is a strong ionic detergent not suitable for all experiments, we have developed a protocol for substituting SDS with a different detergent, such as DDM. Maquette 2 was dissolved in 7 mM SDS and 0.34 mM DDM in 50 mM NaH2PO4, pH 8.0. Addition of a few μL of 3.5 M KCl along with incubation at room temperature for 5 min resulted in precipitation of insoluble potassium dodecyl sulfate. The sample was centrifuged at 14,000 g for 5 min to collect the supernatant containing protein stabilized in DDM [20, 21]. We confirmed spectroscopically that the concentration of the maquette before and after SDS precipitation did not change.

Maquette 2 also has been solubilized in organic solvent (needed for MALDI analysis) by adding acetonitrile to the maquette, followed by sonication, dilution with an equal volume of methanol (MeOH), and further sonication until the protein had completely dissolved.

2.3 Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were recorded with an Aviv 62DS spectropolarimeter in a rectangular quartz cell with 1 mm path length. Temperature was maintained by Neslab CFT-22 recirculating bath at 25 °C. Three consecuti ve scans were performed for each sample. α-helical content of the protein was calculated by using the following equation [22]:

| Equation 1 |

where θ222 is the molar ellipticity at 222 nm and θH and θC are the baseline ellipticities for the helix and random coil respectively. θH and θC have been obtained using the empirical values of Rohl and Baldwin [22]:

| Equation 2 |

| Equation 3 |

where T is temperature in °C and N r is the number of amino acid residues.

2.4. Self-assembly of maquette 1

The equilibrium association of maquette 1 with and without heme B was determined by sedimentation equilibrium in DPC micelles utilizing methods analogous to those used to study other transmembrane peptides [23-25]. The peptides were incorporated into 2 mM DPC micelles, about twice the DPC critical micelle concentration [23]. To eliminate the contribution of the DPC micelles to the peptide's sedimentation, the density of the detergent was adjusted empirically with D2O [26]. Sedimentation equilibrium experiments were conducted at 20°C using a Beckman XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge. The density-matched buffer used was 20 mM NaH2PO4, 100 mM KCl, pH 8, in 51% D2O. The molecular mass and partial specific volume of maquette 1 were calculated with the program Sedinterp [27] using a partial specific volume of 0.82 mL/g for heme [28]. The mass and partial specific volume values were kept fixed when fitting the absorbance versus radius profiles to different equilibrium models. Data obtained were analyzed by nonlinear least-squares curve fitting of radial concentrations profiles by using the Marquardt-Lavenberg algorithm implemented in Igor Pro (Wavemetrics) as previously described [23].

2.5. Assembly of maquettes into lipid vesicles

Vesicles were prepared either by rehydration/sonication (maquette 1 only) or from cosolubilized mixtures of detergents, lipids, and proteins. The lipids, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoylphosphatidylcholine (POPC) and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoylphosphatidylserine (POPS), were obtained pre-dissolved in chloroform from Avanti Polar lipids.

2.5.1 Rehydration/Sonication vesicle incorporation

80:20 POPC:POPS lipid and maquette 1 at a 200:1 lipid:maquette ratio were dissolved in 3:1 chloroform:methanol. Solvent was evaporated under N2 to form a thin film and vacuum dried overnight. The dry mixture was resuspended in buffer (20 mM Tris, 100 mM KCl, pH 8.0), placed in an ice bath, and then sonicated with a Q700 microtip sonicator system (QSonica, LLC) for ten cycles of 30 s on and 30 s off to prevent overheating.

2.5.2 Detergent mediated vesicle incorporation

80:20 POPC:POPS lipid were dried under N2 to form a thin film and then vacuum dried overnight. The dried lipid mixture was dissolved in a detergent buffer containing 0.6% (w/v) octyl-POE, 50mM NaH2PO4 and 100mM NaCl, pH 8.0. The solubilized lipids were kept at room temperature for 5-10 min before adding the maquette. Maquettes 1 and 2 were solubilized in 2 mM DPC and in 7mM SDS, respectively. The solubilized maquette was then added to the lipid solution. The protein-lipid mixture was left at room temperature without any disturbance for 10-15 min. The detergent was removed with Bio-Beads SM-2 (BioRad) according to standard protocol. The total amount of Bio-Beads used in each experiment was always in excess of the reported Bio-Beads capacity (70 −200 mg of detergent per 1 g of Bio-Beads [29, 30]). Specifically, our loading ratio was 14 mg SDS or DPC and 40 mg of octyl-POE per 1 g of Bio-Beads. The Bio-Beads were loaded into empty PD-10 columns (GE Healthcare). The detergent/protein/lipid mixture was added to the Bio-Beads and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 60 min. The resulting proteoliposomes were retrieved by centrifugation at 3000 g for 15 min.

To reconstitute maquette 2 in lipid vesicles with heme B bound, up to one stoichiometric equivalent of heme B was added to the lipid-protein mixture before detergent removal with Bio-Beads. The sample was stirred for 10-15 min and then UV-Vis spectra were recorded to verify heme binding. The remaining one or two equivalents of heme B were added to the proteoliposomes after detergent removal and binding was verified again spectroscopically.

2.6. Cofactor binding analysis

2.6.1 Heme B binding to maquettes

A stock solution of heme B (Fe3+-protoporphyrin IX) was prepared in DMSO for titrations into solutions containing detergent or in 50 mM KOH for titrations that involved lipid vesicles. Heme stock concentrations were verified using the hemochrome assay [31]. Sub-stoichiometric aliquots of heme B were added to proteins assembled into detergents or lipid vesicles (as specified for each experiment) in buffer containing 50mM NaH2PO4 and 100mM NaCl, pH 8.0. These binding titrations were performed over a range of protein concentrations from 100 nM to 2 μM.

2.6.2 Zn2+-protoporphyrin IX (ZnPPIX) binding to maquettes

ZnPPIX stock solution was prepared in DMSO and the stock concentration was determined from absorbance at 427 nm in pyridine based on extinction coefficient ε of 221,000 M−1cm−1 [32]. ZnPPIX titrations were performed as described in 2.6.1.

2.6.3 Binding data analysis

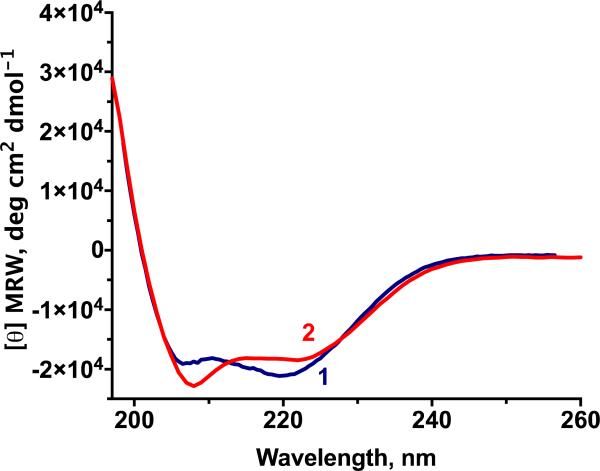

The dissociation constants for up to three cofactors per protein were solved numerically using a custom Mathematica (Wolfram Research) program. To isolate the absorbance increase of only the bound species, we searched for an isosbestic wavelength where the free and bound cofactors have the same extinction coefficients. We were able to identify the isosbestic point for most conditions and plot the difference in absorbance directly related to the bound species. Under these circumstances, the binding curves reached asymptotic value when all binding sites were filled (Figure 5a and Figure 5B, red and blue squares). However, since the spectra of free cofactors are dependent on the solubilizing medium (lipid vesicles, various detergents), it is not always possible to find the isosbestic wavelength, as in heme titrations to AM1 in vesicles (Figure 5B, green circles) and in ZnPPIX titrations (Figure 5C). In these two cases we plot difference in absorbance between the Soret band of bound cofactor and wavelength where the extinction coefficients of bound and unbound cofactors are most similar. This non-zero difference in extinction coefficients prevents the absorbance curves from reaching an asymptotic value (Figure 5B, green circles; Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Cofactor binding titrations. (A) Heme titrations for designs 1 in DPC detergent (purple squares; right y-axis) and in POPC/POPS vesicles (black circles; left y-axis). (B) Heme titrations for designs 2 in SDS (filled red squares) and DDM (open blue squares) detergents and in POPC/POPS vesicles (green circles). (C) ZnPPIX titrations for design 2 in SDS detergent. Solid lines represent fits to binding expressions with Kd values in the Table 1.

Our program is able to determine dissociation constants beyond the first three Kd values if the initial cofactors bind unresolvably tightly under the titrating conditions (i.e. the absorbance increases linearly with the slope equal to the extinction coefficient of the bound cofactor). In such case we can subtract the fully bound equivalents and fit the three subsequent dissociation constants.

2.7 Transient absorption spectroscopy for intra-protein electron transfer

SDS-solubilized protein 2 was diluted in buffer to yield a protein concentration of 4.1 μM in 3 mM SDS, 40 mM Na2HPO4 and 100 mM NaCl at pH 7.9. The protein solution was transferred to a sealed cuvette and purged under argon for 1 hr with gentle stirring. 0.9 molar equivalents of either ZnPPIX alone or heme followed by ZnPPIX were added to the sample. The cuvette was then transferred to a Peltier-equipped cuvette holder at 20 °C and held under vanadyl sulfate scrubbed argon [33].

A 10 Hz Q-switched frequency-doubled Nd:YAG laser (Spectra Physics, 532 nm, 2 ns) focused through a cylindrical lens provided excitation for the photo-activatable ZnPPIX. A ThorLabs mechanical shutter delivered one laser pulse per sec to the sample. A xenon flash source, routed through a split fiber optic cable, illuminated a region of the cuvette subject to the laser excitation pulse as well as a reference region not exposed to the laser. Additional fiber cables collected the two probe beams exiting the cuvette, routing them to the entrance slit of an Acton SP-2156 spectrograph. The reference and laser-excited monochromator output images were focused on Princeton Instruments PiMax-3 ICCD camera with a minimum exposure time of 30 ns. Twenty laser flashes were collected for each time point. A Stanford Research Systems DG 535 digital delay generator controlled signal delays between the laser pump lamp, Q-switch, and xenon probe beams. The kinetics of the absorbance bleach and recovery of the ground state ZnPPIX upon excitation to the triplet state were fit in Mathematica to a stretched exponential with 4 parameters:

| (Equation 4) |

where a, k, and β denote amplitude, rate, and exponential stretching factor respectively.

2.8 Measurements of heme B redox midpoint potentials

Redox potentials of maquettes with 2 hemes bound and assembled in POPC/POPS vesicles were measured by redox potentiometry [34]. Redox titrations were performed in a 1 mL cuvette equipped with stirrer and Ag/AgCl and platinum redox electrodes (MI-800/411, Microelectrodes Inc.). The electrodes were standardized using quinhydrone. All potentials reported are referenced to a standard hydrogen electrode (SHE). All titrations were performed under anaerobic conditions. The sample was stirred and purged with vanadyl sulfate scrubbed argon [33] starting 1 hr before the beginning of the titration. Solution redox potentials were adjusted by small aliquots (~μL) of freshly prepared solutions of sodium dithionite or potassium ferricyanide. Electrode-solution-heme redox mediation was facilitated by redox mediators as follows: 25 μM 2,3,5,6-tethramethyl-p-phenylenediamine (DAD), 25 μM 1,2-naphthaquinone (NQ), 25 μM 2-hydroxy-1.4-naphthoquinone (HNQ), 20 μM phenazine methosulfate (PMS), 20 μM phenazine ethosulfate (PES), 20 μM phenazine (PHE), 20 μM anthraquinone-2-sulfonate (AQS), 20 μM benzyl viologen (BV), 20 μM methyl viologen (MV), 50 μM duroquinone (DQ); 6 μM indigotrisulfonate (ITS), and 10 μM pyocyanine (PC). Stock solutions of all the mediators except BV, MV and PC were made in DMSO. BV, MV and PC were prepared in water. After equilibration at each potential, the heme B optical spectrum was recorded and the course of the reduction of heme B was followed by the increase in the sharp α-band absorption at 559 nm relative to a 575 nm reference wavelength. The data were analyzed with the Nernst equation with n-values of 1.0 for both hemes:

| (Equation 5) |

where R is the fraction of reduced heme, f is the fraction of heme in each site (when both hemes were fully bound, f was kept fixed at 0.5), Eh is the solution redox potential vs. SHE, n=1 is the number of electrons participating in the redox reaction, and Emi is the redox midpoint potential. Analysis of heme redox coupling to proton exchange has been done as previously described [13].

3. Results

3.1 Amphiphilic maquette design

In this work we examine two amphiphilic maquettes, proteins 1 and 2. Both of these proteins were designed to assemble in lipid bilayers, bind hemes at three distinct positions along the length of the helical bundle, and thus support a transmembrane redox chain (Figure 1).

Protein 1 is a symmetric design assembled from four separate and identical helices. Some features of its design draw on aspects of previously reported oligomeric amphiphilic maquettes AP0, AP1, AP2, and AP3 [13]. These earlier proteins each combined sequence information from the soluble maquette HP1 [35] with various hydrophobic sequences designed to anchor each helix into the membrane.

The N-terminal region of protein 1 contains a flexible CGGG loop and 12 amino acid long hydrophilic domain with sequence identical to HP1. The N-terminal cysteine facilitates disulfide-based dimerization, which is necessary for HP1 4-helical self-assembly. However, protein 1 readily self-assembles into 4-helical bundles even without cysteine oxidation. The hydrophilic sequence contains one histidine and assists the tetrameric self-assembly.

Following the hydrophilic domain is a 23 amino acids long membrane-spanning sequence based on helix D from cyt b subunit of bovine heart cytochrome bc1. This sequence contains two histidines that correspond to the bH and bL heme binding sites. 1 has been engineered to assemble as a parallel four-helical bundle with 3 histidines on each helix facing inside the protein. This assembly can potentially bis-His ligate up to 6 hemes or up to 12 Zn-protoporphyrin IX. The distances of 16.5 and 21 Å between the histidines were selected to enable fast electron transfer rates between the bound cofactors.

The symmetry inherent in a tetrameric design such as 1 imposes limits on the mutational flexibility of the protein, as it is not possible to make an isolated mutation at just one of the four helices. To break the symmetry and increase adaptability, we created a new single chain design, protein 2, analogous to the multifunctional single-chain water-soluble maquette A reported by Farid et. al. [5]. This single chain design imposes an antiparallel helical topology.

To form the hydrophilic domain of 2, we exploited the top half of the water-soluble design A [5], specifically 12 N-terminal amino acids from helices one and three, 12 C-terminal amino acids from helices two and four, along with the loop connecting helices two and three. Each helix was then extended into the membrane with a 23 amino acid long “generic” transmembrane sequence rich in leucine and alanine residues. These residues were selected for their high α-helical propensity. The leucine-to-alanine ratio was chosen to match the overall hydrophobicity of the cyt b helices, as determined from the Wimley-White whole-residue octanol scale [36]. The hydrophilic domain contains a pair of heme ligating histidines between helices one and three.

The sequences of all four helices were plotted on polar graphs with a 100° angle per residue, corresponding to straight α-helices with a typical pitch of 3.6 residues per helical turn [13]. The polar graphs revealed that the binary-patterned heptad repeat that has been used for the design of the water-soluble maquette A brings the amino acids out of register for longer helices, specifically for helices two and four. Therefore an extra alanine was introduced near the C-terminal end of helices two and four. Additionally, phenylalanines and tryptophans were added near the edges of the membrane region, consistent with the lower insertion energy of aromatic residues in near the aqueous-membrane interface [37].

To form a transmembrane redox chain similar to the archetypical heme protein ancestor of cytochrome bc1 complex and reaction centers [1, 3], we placed two additional pairs of histidines at two depths within the membrane (Figure 1).

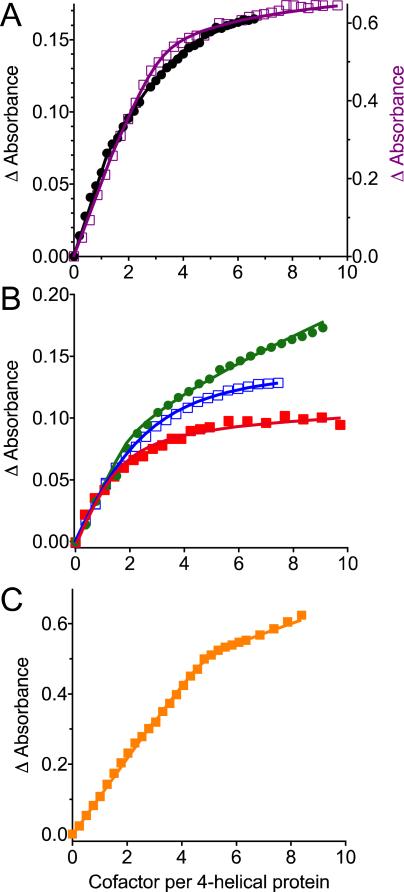

3.2 Folding and helical association

Both designs have α-helix content as seen by circular dichroism (Figure 2). At 25 °C the α-helical content of 1 in 2 mM DPC is ~56% while the α-helical content of 2 in 3 mM SDS is ~49%. There is a tendency for circular dichroism in SDS to underestimate helicity by 9 to 31% [38]. Indeed, the measured helicity of 2 in a different detergent, DDM, is 58%. Helices in both 1 and 2 resist unfolding, requiring heat and urea to begin melting (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 2.

Mean residue molar ellipticities at 25 °C for 1 in 2 mM DPC detergent and 2 in 3 mM SDS both show helical content expected by design.

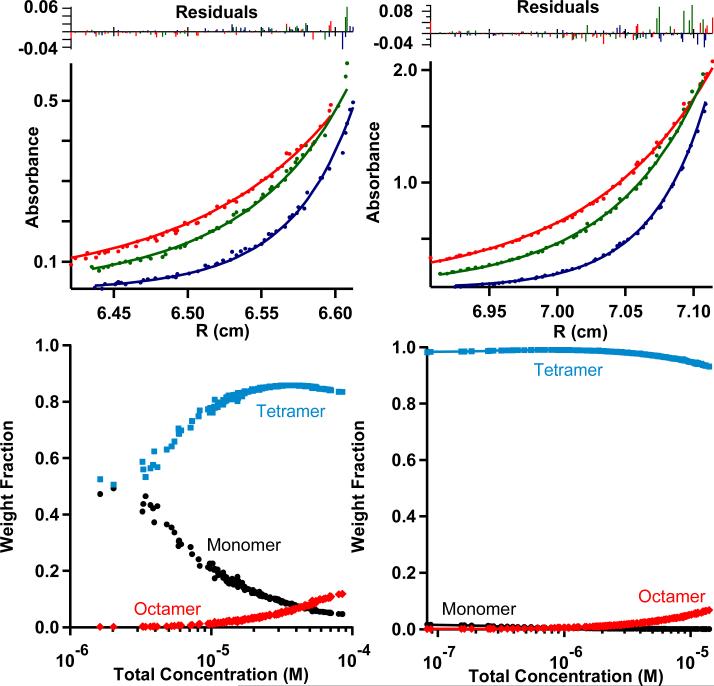

The binary patterning of the water-soluble domain of separate helices in 1 was intended to drive helical association into a bundle even without covalent linkages between independent helices. Analytical ultracentrifugation shows this to be the case (Figure 3). Complete association between helices from the nM to μM concentration range is assured by the addition of just one equivalent of heme per 4 helices. One engineering advantage of the single chain design of 2 is that 4-helix association is virtually guaranteed despite any sequence changes that we introduce to manipulate the physical chemical properties of the bound porphyrin cofactors.

Figure 3.

Concentration dependent association of independent helices of design 1 in detergent solution as seen by analytical ultracentrifu–gation in both the apo (left) and holo (right) forms. At top, absorbances at 280 nm at different radii from the center of the ultracentrifugation cell for three speeds: 40,000 (red), 45,000 (green), and 50,000 rpm (blue) with corresponding fits for molecular weight using the Sedinterp program. The bottom panels depict the weight fractions of the different oligomerization states obtained from the fit.

3.3 Porphyrin cofactor binding

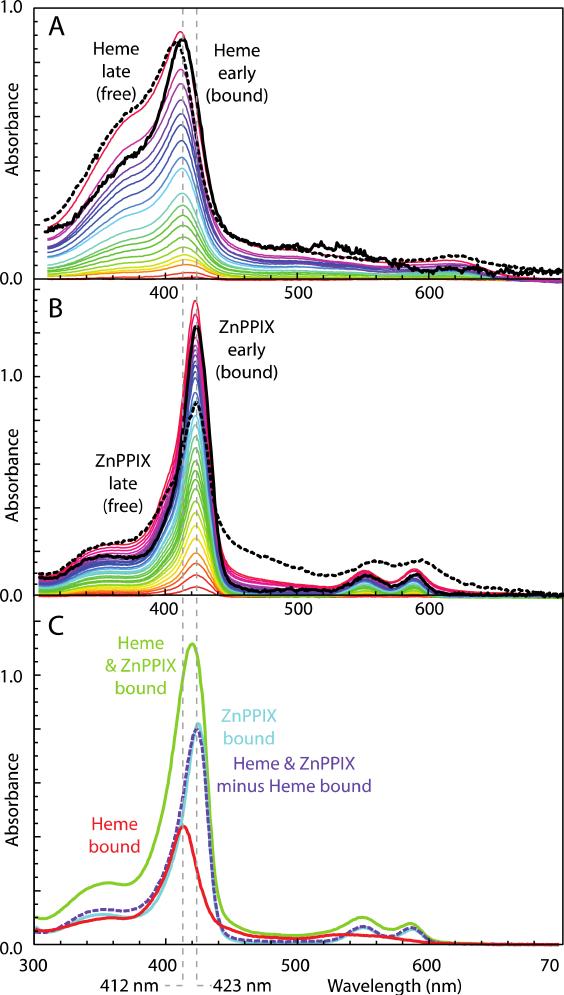

We examined binding of two porphyrin cofactors, Fe- and Zn -protoporphyrin IX (heme B and ZnPPIX) by monitoring the spectral changes of the porphyrin upon ligation to the proteins (Figure 4). Binding of heme B is accompanied by a Soret band shift from ~400 nm (observed for free heme B in detergents or lipid vesicles) to 412 nm, characteristic of bis-histidine ligation. Binding of ZnPPIX is accompanied by a smaller band shift of the sharp Soret band from 419 (bound) to 417 nm (unbound). The difference in absorbance of free and bound ZnPPIX is conspicuous enough for binding analysis (Figure 5C). The binding stoichiometries and Kd values were obtained as described in Methods section 2.6.4 and are reported in Table 1.

Figure 4.

Ligation induced bandshifts on heme binding (A) and ZnPPIX binding (B) to design 2 allow estimates of binding stoichiometry and Kd values. Spectral differences between additions early (black solid line) and late (dashed) in the titrations are vertically expanded to facilitate comparison of ligation-induced bandshifts. (C) Successive addition of 1 equivalent each of heme and ZnPPIX show spectra typical of bound states.

Table 1.

Kd values and observed stoichiometries for heme B (Fe-PPIX) and Zn-PPIX in 1 and 2.

| Maquette | Detergent | Lipid | Cofactor | Max. stoichiometry | Kd1 (nM) | Kd2 (nM) | Kd3 (μM) | Kd4 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 mM DPC | Fe-PPIX | 4 | < 5 | <50 | <0.05 | >1 | |

| 1 | POPC/POPS | Fe-PPIX | 4 | < 5 | 300 | <1 | 1 | |

| 2 | 3 mM SDS | Fe-PPIX | 2 | 50 | 500 | |||

| 2 | DDM | Fe-PPIX | 3 | 50 | 500 | 0.5 | ||

| 2 | POPC/POPS | Fe-PPIX | 3 | 150 | 150 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 2 mM DPC | Zn-PPIX | 8 | Kds < 1μM [41] | ||||

| 2 | 3 mM SDS | Zn-PPIX | 5 | Kd1-4 < 50 nM, Kd5 100 nM | ||||

Although 1 was designed to bind up to 6 hemes B, we observed that only three binding sites have sub-μM affinity, both in DPC detergent and in lipid vesicles (Figure 5, Table 1). The heme B binding to these sites was robust from pH 5 to 9. Protein 2, designed with 3 bis-His sites, binds the first two hemes B with noticeably stronger affinity than the third. We observed sub-μM heme B binding to the third site of 2 only when assembled in DDM. Heme binding in design 2 is not as robust at low pH as in design 1, weakening when the pH is dropped to 6, perhaps because of protonation of a heme ligating His residue. We expect heme binding to improve when we diversify the all Ala and Leu bundle interior of 2 with phenylalanines between the transmembrane heme binding sites.

While iron in heme B prefers hexacoordinate bis-His ligation, ZnPPIX inserts into the same sites with pentacoordinate binding to just one His residues (Figure 4B). Figure 5 shows that up to 5 ZnPPIX cofactors can bind to 2. The first four have unresolvably tight Kd values; the fifth has 100 nM affinity (Table 1).

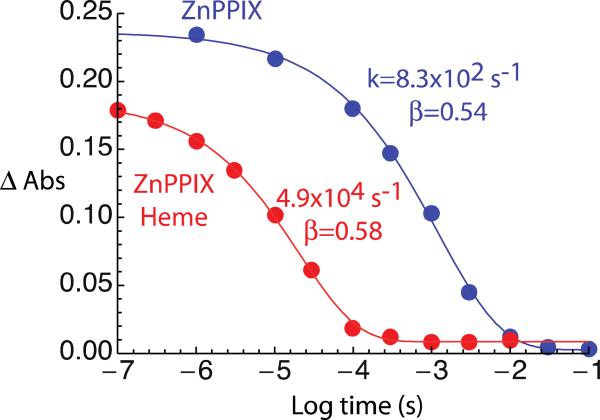

3.4 Mixed porphyrin light activated electron transfer

Successive addition of heme and ZnPPIX porphyrin (Figure 4C) generates mixed porphyrin arrays that may initiate light activated electron transfer akin to water-soluble maquette counterparts [5]. Unlike the symmetric tetramer 1, the single chain design of 2 permits design of separate bis-His and single-His sites to enable site-specific heme and Zn porphyrin binding. However, even without introducing such site specificity, 2 demonstrates kinetics consistent with photo-induced electron transfer between a single ZnPPIX and heme B cofactor. Figure 6 shows that the ms-scale excited state lifetime for ZnPPIX alone is quenched by the addition of heme, reducing the lifetime to ~10 μs. These results are consistent with a charge separation from ZnPPIX to oxidized heme over a distance of ~21 Å. In this simple dyad, the free energy change driving charge recombination to ZnPPIX ground state is expected to be faster than the initial charge separation so minimal reduced heme intermediate is observed.

Figure 6.

The decay of the light activated triplet of ZnPPIX in 2 (blue) follows a slightly stretch exponential with a rate of 830 s−1 (β=0.54). With heme present (red), the triplet decays faster at 4.9×104 s−1 with a greater exponential stretch (β=0.58) consistent with electron transfer quenching at an edge-to-edge distance of ~21 Å.

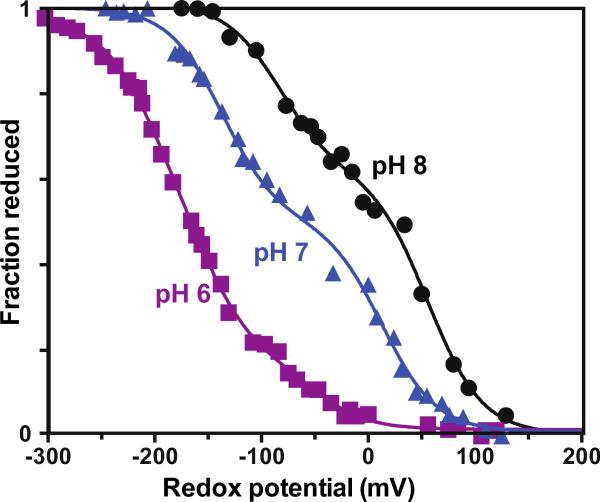

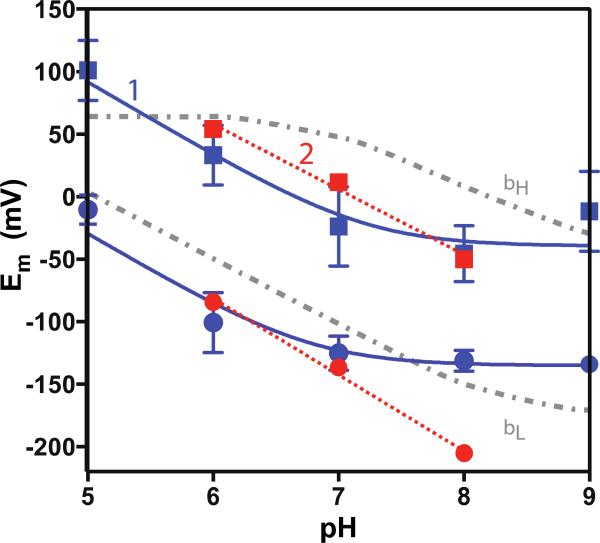

3.5 Redox properties

Equilibrium redox titrations of hemes bound to 1 and 2 show split heme redox midpoint potentials (Figure 7 and 8). Midpoint potential splitting is to be expected, if only because hemes buried far from the polar aqueous phase are generally easier to reduce and have higher midpoint potentials compared to hemes more exposed to water [39]. The pH dependence of both midpoint potentials in 1 indicate a reduced heme pK around pH 6.8, while no such pK is obvious in design 2. The redox potential splitting is similar to that observed in native cytochrome bc1 complex [40].

Figure 7.

Redox titrations of 2 equivalents of heme added to maquette 2. At pH 6, protonation of ligating His becomes more likely and less of the higher potential heme appears to be bound.

Figure 8.

Redox midpoint potential split between heme sites in 1 (blue) and 2 (red) as a function of pH. A pKred around 6.8 is observed in 1 but not 2. Heme Em values in Rb. sphaeroides bc1 complex shown in grey.

4. Discussion

In this work, we have advanced the engineering principles required for the design of amphiphilic proteins equipped with multiple redox-active cofactors akin to those supporting transmembrane electron transport in respiration and photosynthesis. Binary patterning that has proven useful for directing helical bundle association in water-soluble synthetic proteins [4, 11] can also be applied to the construction of transmembrane proteins, provided that the binary patterned water-soluble domain is large enough. It is also clear that including interhelical connections provided by added bis-His ligated cofactors further favors four-helical bundle association in detergent or membranes. We have shown in design 1 that without the presence of a bis-His heme cofactor providing a link between independent helices, there is a residual tendency for helices to disassociate at the lowest sub-μM protein concentrations and that adding a single heme eliminates this tendency. Detergent and membrane soluble synthetic proteins lacking a sufficiently large water-soluble domain tend to have weaker helical associations in the apo form. For example, a recent computationally designed amphipathic heme binding protein without a conspicuous water soluble domain [42] forms separate 2-helix units, even at high protein concentrations, unless bis-His ligated heme is bound to create interhelical links to form a 4-helix bundle. Similarly, a 4-helix hydrophobic synthetic protein designed to transport ions across membranes [43] showed a tendency to form 2-helix subunits in DPC, although the yield of 4-helix units improves on binding metals or moving into lipid membranes. The single chain design 2 provides a stronger entropic force for four-helical transmembrane bundle assembly, which could eliminate the need for the water-soluble domain, if there were reason to make a more compact protein. However, electron transfer with redox partners in the cytoplasmic or periplasmic space in vivo would be more difficult in such designs.

The redox midpoint potentials of the hemes in 1 and 2 are split by ~120 mV with a conspicuous pH dependence. The pH dependence, midpoint potential range and split roughly resemble the hemes bH and bL in the bc1 complex [40]. We notice a near 50:50 contribution of split heme potentials even when just one heme is added to the bundle. Because heme-binding titrations indicate tight binding of the first two hemes, it is not presently possible to distinguish between two possibilities: independent tight binding of hemes to two different sites with inherently different redox properties (e. g. aqueous phase and membrane buried sites) or cooperative binding of two hemes within a single bundle. The latter possibility would arise if binding one heme organizes the bundle to assist binding of a second heme. These questions will be addressed in modifications of the single chain sequence 2 that separately knock out His in the three sites and disable bis-His ligation of heme in these locations, while still allowing ligation of ZnPPIX. Notably, a single glycine-to-phenylalanine mutation in an amphiphilic heme-binding construct based on glycophorin A produces a 50 mV midpoint change [44]. Future designs could explore how similar changes to internal residues impact midpoint potentials.

The His sites of both 1 and 2 bind either a Fe containing heme or the Zn counterpart, ZnPPIX. A variety of other tetrapyrroles, including bacteriochlorophylls, have also been shown to bind to amphiphilic maquettes [45]. Because heme is bis-His ligated while ZnPPIX requires only a single His for ligation, in principle the binding stoichiometry of ZnPPIX can be higher than that for heme. Figure 5 shows that design 2 can bind a maximum of 5 ZnPPIX compared to 3 hemes. Some natural membrane proteins show an analogous flexibility in vivo, binding either heme or a light activatable Mg-tetrapyrrole [1]. Under aerobic conditions, R. capsulatus expresses the heme protein cyt b561 with a midpoint potential of −65 mV [46]. This protein is a dimer of light harvesting LHII-β polypeptide. Under anaerobic photosynthetic conditions, this same protein instead binds Mg-bacteriochlorophyll and assembles, together with the α subunit, into the photosynthetic LHII light-harvesting complex. The hypothesis that a cytochrome b-like protein is ancestral to modern cytochrome bc1, b6f and reaction center proteins presumes that certain proteins were able to bind both types of tetrapyrroles and be subject to natural selection [1, 3]. Cyt b561, 1 and 2 provide modern examples. Indeed, Figure 4 shows that 2 simultaneously binds heme and light active ZnPPIX, while Figure 6 shows that it participates in the electron-transfer induced quenching of the light excited ZnPPIX pigment. Thus the mixed porphyrin assembly of maquette 2 is an analog of the proposed ancestral b-type protein that bound light activated pigments first for dissipative photo-protection during the gradual transition to productive photochemistry during the origin of photosynthesis [3].

The 10 μs characteristic time of heme induced quenching of the excited ZnPPIX triplet in Figure 6, combined with an expected driving force of 0.6 to 0.8 eV for photoreduction of the heme and a reorganization energy ~0.9 eV as reported in other maquette designs [5], indicates an edge-to-edge electron tunneling distance of ~21 Å [47]. This distance is comparable to the separation of the two membrane spanning tetrapyrrole binding sites in 2, estimated from the 14 residue separation of ligating His residues (helix pitch of ~1.5 Å per residue) and the spacing of helices in the bundle. An uncertainty of up to 5 Å arises from the presently unknown orientation of the peripheral groups of the cofactors within bundle. In fact some of the stretch of the exponential fit (β=0.58) may be due to a relatively small distribution of distances within the structure. The distance between the aqueous domain site and the proximal transmembrane site should be ~4 Å shorter, which would drive electron-tunneling rates into the ns time scale. If such rapid electron transfer is occurring, it may be effectively unresolved with our gated camera detector. Indeed, it is possible that the initial lower amplitude of the ZnPPIX triplet state signal in the presence of heme at 100 nsec in Figure 6 is at least partly due to some rapid electron transfer over this shorter distance. On the other hand, the distance between the aqueous domain site and the distal porphyrin site is estimated at ~8 Å longer; at this distance electron tunneling will be much longer than the ZnPPIX lifetime in the absence of heme. Because only short ZnPPIX lifetimes are observed in the mixed tetrapyrrole system, we do not expect maquettes to assume this distant cofactor geometry.

Detailed computation and empirical/first principles designs present complimentary approaches in producing synthetic proteins. Various engineered tetrahelical bundle proteins, some binding natural and synthetic tetrapyrroles, have been designed computationally, both as water-soluble [43, 48-52] and amphiphilic [15] constructs. Computationally-designed proteins may then be optimized through “post-design” empirical modification. For example, the di-metal cofactor binding protein in [52] was modified to eliminate unwanted dimerization in an aqueous environment. Molecules 1 and 2 presented here were designed with minimal computation. 1 combines natural membrane-bound sequence from bc1 with the empirically designed hydrophilic sequence from previous maquette designs. 2 instead employs a simpler first principles leucine and alanine-rich hydrophobic region connected by flexible loops in a single chain.

This amphipathic single chain transmembrane 4-helix bundle frame is intentionally adaptable to allow us to uncover the practical engineering limits of robust transmembrane electron-transfer protein construction for light activated electron transfer, intraprotein electron transfer with redox protein partners in the aqueous phase (see this issue [53]) as well as electron transfer with redox carriers in the membrane. We have preliminary evidence of transmembrane heme maquette designs that catalyze electron transfer between ubiquinol and cytochrome c, formally analogous to catalysis of natural bc1 complex proteins [54]. The present work shows that the physical chemical properties of the symmetric helical tetramer design 1 are preserved in advancing to the monomeric and simplified sequence design 2. We now have the opportunity to exploit asymmetries in the sequence as we engineer differences between tetrapyrrole binding sites and differences in aqueous phase charge patterning. Our long-term view aims to express these proteins in vivo with self-assembly of natural redox cofactors and the ability to intersect with natural electron-transfer pathways of metabolism with the goal of rewiring natural electron transfer systems for human goals such as fuel production. We are presently introducing bis-His and single-His site specificity to tetrapyrrole binding sites and plan to expand site specificity by introducing the CXXCH motif that has been successful in securing c-type hemes during E. coli expression in hydrophilic counterparts of this design [55]. These changes will allow us to more tightly control the properties of tetrapyrrole cofactors at individual sites with specific separations, solvent exposures, and electron tunneling driving forces. These improvements will offer more precise tracking of individual steps in both inter- and intra-protein electron transfer and ultimately will pave the way toward recapitulating the design origins of photosynthesis.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Single chain man-designed transmembrane protein binds active tetrapyrrole chain

Heme and light-active tetrapyrrole assembly resembles ancestral photosynthetic proteins

Maquette platform reveals transmembrane oxidoreductase construction engineering

Acknowledgements

The design and characterization of protein 1 was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award #GM48130; design, expression, purification, and cofactor binding for protein 2 was supported by the Nano/Bio Interface Center NSF NSEC DMR08-32802; redox characterization of protein 2 was supported by NSF Accelerating Innovation in Research program AIR ENG-1312202; and the mixed porphyrin light activated electron transfer research was supported by the Photosynthetic Antenna Research Center (PARC), an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences under Award # DE-SC0001035.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Xiong J, Bauer CE. A Cytochrome b Origin of Photosynthetic Reaction Centers: an Evolutionary Link between Respiration and Photosynthesis. Journal of molecular biology. 2002;322:1025–1037. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00822-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell P. The protonmotive Q cycle: a general formulation. FEBS Letters. 1975;59:137–139. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(75)80359-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mulkidjanian AY, Junge W. On the origin of photosynthesis as inferred from sequence analysis. Photosynthesis research. 1997;51:27–42. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robertson DE, Farid RS, Moser CC, Urbauer JL, Mulholland SE, Pidikiti R, Lear JD, Wand AJ, DeGrado WF, Dutton PL. Design and Synthesis of Multi-Heme Proteins. Nature. 1994;368:425–431. doi: 10.1038/368425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farid TA, Kodali G, Solomon LA, Lichtenstein BR, Sheehan MM, Fry BA, Bialas C, Ennist NM, Siedlecki JA, Zhao Z, Stetz MA, Valentine KG, Anderson JLR, Wand AJ, Discher BM, Moser CC, Dutton PL. Elementary tetrahelical protein design for diverse oxidoreductase functions. Nature Chemical Biology. 2013;9:826–833. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibney BR, Mulholland SE, Rabanal F, Dutton PL. Ferredoxin and ferredoxin-heme maquettes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:15041–15046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grzyb J, Xu F, Weiner L, Reijerse EJ, Lubitz W, Nanda V, Noy D. De novo design of a non-natural fold for an iron-sulfur protein: alpha-helical coiled-coil with a four-iron four-sulfur cluster binding site in its central core. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2010;1797:406–413. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharp RE, Moser CC, Rabanal F, Dutton PL. Design, synthesis, and characterization of a photoactivatable flavocytochrome molecular maquette. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1998;95:10465–10470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lichtenstein BR, Moorman VR, Cerda JF, Wand AJ, Dutton PL. Electrochemical and structural coupling of the naphthoquinone amino acid. Chemical Communications. 2012;48:1997–1999. doi: 10.1039/c2cc16968a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koder RL, Anderson JLR, Solomon LA, Reddy KS, Moser CC, Dutton PL. Design and engineering of an O2 transport protein. Nature. 2009;458:305–309. doi: 10.1038/nature07841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regan L, DeGrado WF. Characterization of a helical protein designed from first principles. Science. 1988;241:976–978. doi: 10.1126/science.3043666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Discher BM, Moser CC, Koder RL, Dutton PL. Hydrophilic to amphiphilic design in redox protein maquettes. Current opinion in chemical biology. 2003;7:741–748. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Discher BM, Noy D, Strzalka J, Ye S, Moser CC, Lear JD, Blasie JK, Dutton PL. Design of amphiphilic protein maquettes: controlling assembly, membrane insertion, and cofactor interactions. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12329–12343. doi: 10.1021/bi050695m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cordova JM, Noack PL, Hilcove SA, Lear JD, Ghirlanda G. Design of a Functional Membrane Protein by Engineering a Heme-Binding Site in Glycophorin A. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;129:512–518. doi: 10.1021/ja057495i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korendovych IV, Senes A, Kim YH, Lear JD, Fry HC, Therien MJ, Blasie JK, Walker FA, DeGrado WF. De Novo Design and Molecular Assembly of a Transmembrane Diporphyrin-Binding Protein Complex. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2010;132:15516–15518. doi: 10.1021/ja107487b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eleff S, Kennaway NG, Buist NR, Darley-Usmar VM, Capaldi RA, Bank WJ, Chance B. 31P NMR study of improvement in oxidative phosphorylation by vitamins K3 and C in a patient with a defect in electron transport at complex III in skeletal muscle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1984;81:3529–3533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.11.3529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tillett D, Neilan BA. Enzyme-free cloning: a rapid method to clone PCR products independent of vector restriction enzyme sites. Nucleic acids research. 1999;27:e26–e28. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.19.e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodríguez-Carmona E, Cano-Garrido O, Seras-Franzoso J, Villaverde A, García-Fruitós E. Isolation of cell-free bacterial inclusion bodies. Microbial Cell Factories. 2010;9:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-9-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rath A, Glibowicka M, Nadeau VG, Chen G, Deber CM. Detergent binding explains anomalous SDS-PAGE migration of membrane proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:1760–1765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813167106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou J-Y, Dann GP, Shi T, Wang L, Gao X, Su D, Nicora CD, Shukla AK, Moore RJ, Liu T, Camp DG, II, Smith RD, Qian W-J. Simple Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Assisted Sample Preparation Method for LC-MS-Based Proteomics Applications. Analytical Chemistry. 2012;84:2862–2867. doi: 10.1021/ac203394r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dreher C, Prodöhl A, Weber M, Schneider D. Heme binding properties of heterologously expressed spinach cytochrome b6: Implications for transmembrane b-type cytochrome formation. Febs Letters. 2007;581:2647–2651. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rohl CA, Baldwin RL. Comparison of NH Exchange and Circular Dichroism as Techniques for Measuring the Parameters of the Helix–Coil Transition in Peptides. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8435–8442. doi: 10.1021/bi9706677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kochendoerfer GG, Salom D, Lear JD, Wilk-Orescan R, Kent S, DeGrado WF. Total chemical synthesis of the integral membrane protein influenza A virus M2: Role of its C-terminal domain in tetramer assembly. Biochemistry. 1999;38:11905–11913. doi: 10.1021/bi990720m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salom D, Hill BR, Lear JD, DeGrado WF. pH-dependent tetramerization and amantadine binding of the transmembrane helix of M2 from the influenza A virus. Biochemistry. 2000;39:14160–14170. doi: 10.1021/bi001799u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howard KP, Lear JD, DeGrado WF. Sequence determinants of the energetics of folding of a transmembrane four-helix-bundle protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:8568–8572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132266099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanford C, Nozaki Y, Reynolds JA, Makino S. Molecular Characterization of Proteins in Detergent Solutions. Biochemistry. 1974;13:2369–2376. doi: 10.1021/bi00708a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laue T, Shah B, Ridgeway T, Pelletier S. Computer-aided Interpretation of Sedimentation Data for Proteins. In: Harding SE, Rowe AJ, Horton JC, editors. Analytical Ultracentrifugation in Biochemistry and Polymer Science. The Royal Society of Chemistry; Cambridge, U. K.: 1992. pp. 90–125. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayer G, Anderka O, Ludwig B, Schubert D. The state of association of the cytochrome bc1 complex from Paracoccus denitrificans in solutions of dodecyl maltoside. Progress in Colloid and Polymer Science, Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 2002:77–83. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lacapère J-J, Delavoie F, Li H, Péranzi G, Maccario J, Papadopoulos V, Vidic B. Structural and Functional Study of Reconstituted Peripheral Benzodiazepine Receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;284:536–541. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rigaud JL, Mosser G, Lacapere JJ, Olofsson A, Levy D, Ranck JL. Bio- beads: An efficient strategy for two-dimensional crystallization of membrane proteins. Journal of Structural Biology. 1997;118:226–235. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1997.3848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berry EA, Trumpower BL. Simultaneous determination of hemes a, b, and c from pyridine hemochrome spectra. Anal Biochem. 1987;161:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90643-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farid TA. Thesis. University of Pennsylvania; 2012. Engineering an artificial, multifunctional oxidoreductase protein maquette. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Englander SW, Calhoun DB, Englander JJ. Biochemistry Without Oxygen. Anal Biochem. 1987;161:300–306. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90454-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dutton PL. Redox potentiometry: Determination of midpoint potentials of oxidation-reduction components of biological electron-transfer systems. Methods Enzymol. 1978 doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)54026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang SS, Koder RL, Lewis M, Wand AJ, Dutton PL. The HP-1 maquette: from an apoprotein structure to a structured hemoprotein designed to promote redox-coupled proton exchange. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004;101:5536–5541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306676101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wimley WC, Creamer TP, White SH. Solvation energies of amino acid side chains and backbone in a family of host-guest pentapeptides. Biochemistry. 1996;35:5109–5124. doi: 10.1021/bi9600153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wimley WC, White SH. Experimentally determined hydrophobicity scale for proteins at membrane interfaces. Nature Structural Biology. 1996;3:842–848. doi: 10.1038/nsb1096-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Polet H, Steinhardt J. Binding-induced alterations in ultraviolet absorption of native serum albumin. Biochemistry. 1968;7:1348–1356. doi: 10.1021/bi00844a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gibney BR, Huang SS, Skalicky JJ, Fuentes EJ, Wand AJ, Dutton PL. Hydrophobic modulation of heme properties in heme protein maquettes. Biochemistry. 2001;40:10550–10561. doi: 10.1021/bi002806h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang H, Chobot SE, Osyczka A, Wraight CA, Dutton PL, Moser CC. Quinone and non-quinone redox couples in Complex III. Journal of bioenergetics and biomembranes. 2008;40:493–499. doi: 10.1007/s10863-008-9174-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kathan-Galipeau K, Nanayakkara S, O'Brian PA, Nikiforov M, Discher BM, Bonnell DA. Direct probe of molecular polarization in de novo protein-electrode interfaces. ACS nano. 2011;5:4835–4842. doi: 10.1021/nn200887n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mahajan M, Bhattacharjya S. Designed Di - Heme Binding Helical Transmembrane Protein. ChemBioChem. 2014;15:1257–1262. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joh NH, Wang T, Bhate MP, Acharya R, Wu Y, Grabe M, Hong M, Grigoryan G, DeGrado WF. De novo design of a transmembrane Zn2+ -transporting four-helix bundle. Science. 2014;346:1520–1524. doi: 10.1126/science.1261172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shinde S, Cordova JM, Woodrum BW, Ghirlanda G. Modulation of function in a minimalist heme-binding membrane protein. Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry. 2012;17:557–564. doi: 10.1007/s00775-012-0876-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Noy D, Discher BM, Rubtsov IV, Hochstrasser RA, Dutton PL. Design of amphiphilic protein maquettes: Enhancing maquette functionality through binding of extremely hydrophobic cofactors to lipophilic domains. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12344–12354. doi: 10.1021/bi050696e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bartsch RG, Caffrey MS, Vanbeeumen JJ, Salamon Z, Tollin G, Meyer TE, Cusanovich MA. Purification and Properties of an Unusual Membrane-Derived Cytochrome b-561 from the Purple Phototrophic Bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus, Which Is Structurally Related to the Bacteriochlorophyll-Binding Protein, LHIIβ. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1993;304:117–122. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moser CC, Keske JM, Warncke K, Farid RS, Dutton PL. Nature of Biological Electron-Transfer. Nature. 1992;355:796–802. doi: 10.1038/355796a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ghirlanda G, Osyczka A, Liu WX, Antolovich M, Smith KM, Dutton PL, Wand AJ, DeGrado WF. De novo design of a D-2-symmetrical protein that reproduces the diheme four-helix bundle in cytochrome bc(1) Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2004;126:8141–8147. doi: 10.1021/ja039935g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cochran FV, Wu SP, Wang W, Nanda V, Saven JG, Therien MJ, DeGrado WF. Computational de novo design and characterization of a four-helix bundle protein that selectively binds a nonbiological cofactor. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2005;127:1346–1347. doi: 10.1021/ja044129a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bender GM, Lehmann A, Zou H, Cheng H, Fry HC, Engel D, Therien MJ, Blasie JK, Roder H, Saven JG, DeGrado WF. De novo design of a single-chain diphenylporphyrin metalloprotein. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129:10732–10740. doi: 10.1021/ja071199j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fry HC, Lehmann A, Saven JG, DeGrado WF, Therien MJ. Computational Design and Elaboration of a de Novo Heterotetrameric alpha-Helical Protein That Selectively Binds an Emissive Abiological (Porphinato)zinc Chromophore. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2010;132:3997–4005. doi: 10.1021/ja907407m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fry HC, Lehmann A, Sinks LE, Asselberghs I, Tronin A, Krishnan V, Blasie JK, Clays K, DeGrado WF, Saven JG, Therien MJ. Computational de Novo Design and Characterization of a Protein That Selectively Binds a Highly Hyperpolarizable Abiological Chromophore. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2013;135:13914–13926. doi: 10.1021/ja4067404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fry BA, Solomon LA, Dutton PL, Moser CC. Design and engineering of a man-made diffusive electron-transport protein. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta Bioenergetics. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.09.008. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hokanson SC. PhD Thesis. Univ. of Pennsylvania; 2010. Deconvoluting the engineering and assembly instructions for complex III activity. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anderson JLR, Armstrong CT, Kodali G, Lichtenstein BR, Watkins DW, Mancini JA, Boyle AL, Farid TA, Crump MP, Moser CC, Dutton PL. Constructing a man-made c-type cytochrome maquette in vivo: electron transfer, oxygen transport and conversion to a photoactive light harvesting maquette. Chemical Science. 2014;5:507–514. doi: 10.1039/C3SC52019F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.