Abstract

Purpose

Exercise self-efficacy is one of the strongest predictors of physical activity behavior. Prior literature suggests that tai chi, a mind-body exercise, may increase self-efficacy, however this is not well-studied. Little is known about the factors associated with development of exercise self-efficacy in a heart failure population.

Methods

We utilized data from a randomized controlled trial of 12 weeks group tai chi classes vs. education in patients with chronic heart failure (N=100). We used multivariable linear regression to explore possible correlates of change in exercise self-efficacy in the entire sample, and in the subgroup who received tai chi (N=50). Covariates included baseline quality-of-life, social support, functional parameters, physical activity, serum biomarkers, sociodemographics, and clinical HF parameters.

Results

Baseline 6-minute walk (β= −0.0003;SE 0.0001;p=0.02) and fatigue score (β= 0.03;SE 0.01;p=0.004) were significantly associated with change in self-efficacy, with those in the lowest tertile for 6-minute walk and higher tertiles for fatigue score having the greatest change. Intervention group was highly significant, with self-efficacy significantly improved in the tai chi group compared to the education control over 12 weeks (β= 0.39;SE: 0.11;p< 0.001). In the tai chi group alone, lower baseline oxygen consumption (β= −0.05;SE 0.01;p=0.001), decreased mood (β= −0.01;SE 0.003;p=0.004), and higher catecholamine level (epinephrine β= 0.003;SE 0.001;p=0.005) were significantly associated with improvements in self-efficacy.

Conclusions

In this exploratory analysis, our initial findings support the concept that interventions like tai chi may be beneficial in improving exercise self-efficacy, especially in patients with heart failure who are deconditioned, with lower functional status and mood.

Keywords: Exercise, Self-efficacy, Heart failure

Introduction

Exercise is an important component of best practice guidelines for chronic heart failure (HF). Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have concluded that exercise training reduces HF-related hospitalizations and results in clinically important improvements in health-related quality-of-life. Even moderate amounts of activity have physiological, functional, and psychological health benefits.(1) Unfortunately however, adherence to physical activity and exercise is universally challenging, particularly among the older population and those with chronic illness, and successful methods for promoting and sustaining activity are lacking.(2,3) Research into approaches that facilitate increased physical activity in these chronic disease populations is ongoing.

One consistent finding is that exercise self-efficacy is one of the strongest predictors of physical activity behavior, in HF as well as other chronic disease, independent of disease severity or level of physical impairment.(4) Self-efficacy is a psychological construct based on social cognitive theory that describes the interaction between behavioral, personal, and environmental factors in health and chronic disease. The theory of self-efficacy proposes that patients’ confidence in their ability to perform certain health behaviors influences their engagement in and actual performance of those behaviors (e.g., diet and exercise adherence), which in turn influences health outcomes. Importantly, self-efficacy is a modifiable characteristic. Thus it has been suggested that better understanding and targeting exercise self-efficacy is paramount when trying to facilitate increased physical activity.(5,6,7,8,9,10) The Heart and Soul Study demonstrated that baseline cardiac self-efficacy predicted subsequent hospitalizations for HF and all-cause mortality and was a proxy for baseline cardiac function.(11)

Tai chi is a gentle, meditative exercise with origins in Chinese martial arts that may help promote exercise self-efficacy. Tai chi incorporates cultivation of mindfulness, slow deep breathing, and low-impact physical exercise. Importantly, it has been described as modifiable, non-threatening, accessible to the elderly and deconditioned, and prior studies have suggested increases in self-efficacy (12, 13, 14, 15). We have previously reported that a 12 week tai chi program in patients with HF was effective in increasing exercise self-efficacy, as well as disease-specific quality of life and mood, as compared to an education control. (16) Within this dataset, the current study further explores the correlates of this change in self-efficacy to better understand what patient sociodemographic, clinical, or physiological characteristics in patients with HF are associated with change in self-efficacy in the overall cohort and specifically in those who received tai chi.

Methods

Study Sample, Recruitment, and Intervention

Detailed methods of the randomized controlled trial are reported elsewhere (16). In brief, we recruited 100 patients with chronic systolic heart failure (left ventricular ejection fraction <=40%, stable medical regimen, New York Heart Association class 1–3) from HF specialty clinics and primary care at several large academic medical centers in Boston. Patients were randomized to either 12-weeks of group tai chi exercise or an education attention control). All participants continued to receive their usual medical care and medications as prescribed. Details regarding participant flow, CONSORT diagram, and intervention are included in the first publication describing primary outcomes of this trial. The tai chi intervention consisted of one-hour group classes held twice weekly for 12 weeks and included traditional warm-up exercises followed by five simplified tai chi movements adapted from Master Cheng Man-Ch’ing’s Yang-style short form. Patients were encouraged to practice at home at least three times per week with an instructional videotape. The education control sessions also met twice weekly and followed the printed content of the Heart Failure Society of America education modules. Participants in tai chi also received the same education modules weekly. One patient in the tai chi group, and three patients in the education group discontinued the intervention and were lost to follow up. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at each academic center, with primary recruitment sites being the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Data Collection and Measures

Measurements were collected at baseline, 6 and 12 weeks by assessors blinded to group allocation.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Factors

Patients were queried about race, ethnicity, gender, age. Etiology of HF and LVEF were obtained from medical record review. Resting heart rate was collected at the baseline visit.

Psychosocial Measures

Exercise self-efficacy was measured using the Cardiac Exercise Self-Efficacy Instrument, a validated 16-item scale assessing confidence to perform certain exercise-related activities on a 5-point scale. Score range is 16–80, with higher scores denoting increased self-efficacy.(17) Validated instruments of health-related quality-of-life (HRQL) and psychosocial functioning included the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHF), the SF-12v2 Short Form Health Survey, and the Profile of Mood States (POMS). For disease-specific quality of life, we used the MLHFQ, consisting of 21 validated items covering physical, psychological, and socioeconomic dimensions. The score range is 0 to 105, with a lower number denoting better quality of life. Prior studies have reported that a score of ≥7 indicates some degree of impaired quality of life and that an improvement of 5 points represents a clinically significant change.(18) For general HRQL, we employed the SF-12v2, a widely used health survey with 12 questions covering both physical and mental dimensions in eight different domains (physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional, and mental health). We also used the Profile of Mood States, a well-validated instrument for assessing emotional states that are transient and expected to respond to clinical intervention. The instrument consists of 65 single-word items rated on a 5-point scale to indicate recent mood in 6 dimensions: anxiety, depression, anger, vigor, fatigue, and confusion. A decreased total mood disturbance score denotes an improved emotional state.(19)

Exercise Capacity and Functional Status

Patients performed a symptom-limited exercise test to determine peak VO2 using a bicycle ramp protocol with expired gas analysis under continuous electrocardiographic monitoring. Breath-by-breath respiratory gas analysis was performed using a metabolic cart (Med-Graphics, St. Paul, Minnesota). Peak values were averaged from the final 20 seconds of the test. In addition, patients underwent a 6-minute walk test, a standardized assessment that measures the distance walked in meters down a corridor.(20) The test was done on each of three occasions, at least 2 hours before the bicycle ergometer test, using scripted instructions according to ATS guidelines. Subjects were allowed to stop as needed if they fatigued and were informed when there were 3 and 1 minute(s) remaining. We also performed a Timed Up and Go functional assessment, which measures the time needed for individuals to stand up from a chair, walk 3 meters, turn around a cone, walk back, and return to a seated position as quickly as possible.(21) Level of physical activity at baseline was measured using the CHAMPS Physical Activity Questionnaire for Older Adults. (22)

Biomarkers

B-type natriuretic peptide was analyzed on whole blood collected in EDTA using a commercially available point-of service meter (fluorescence immunoassay; Biosite Triage BNP Test; Biosite Diagnostics, San Diego, California). Serum samples for measurement of catecholamines (epinephrine, norepinephrine, and dopamine) were collected from an intravenous catheter and stored on ice after 20 minutes of patients resting in a supine position. We also analyzed samples for C-reactive protein, endothelin-1, and tumor necrosis factor.

Statistical Analysis

We analyzed data using SAS Statistical Software (version 9.3, 2011, SAS Institute Inc). We conducted bivariable analysis modeling change in cardiac exercise self-efficacy in 12 weeks as a function of baseline (1) quality of life (both disease-specific and generic), profile of mood states, sense of coherence, perceived social support, (2) 6 minute walk test, bicycle metabolic stress test, timed get-up and go function (TUG), physical activity, as well as (3) biomarkers including epinephrine, norepinephrine, dopamine, C-reactive protein (CRP), tumor necrosis factor, endothelin 1, and B-type natriuretic peptide. Additional analysis included bivariable models between change in self-efficacy and age, sex, race (white or not), ischemic etiology, baseline ejection fraction, baseline resting heart rate, and intervention group. Significant covariates then served as candidates for forward selection models to explore the correlates and mechanisms of change in self-efficacy. We forced known confounders into a multiple regression model, including age, gender, baseline ejection fraction, and intervention group. We first examined the entire sample, including both intervention groups. We then further explored correlates of exercise self-efficacy, specifically in the subgroup who received tai chi, utilizing the same analysis strategy. The final model utilizing the entire sample was further examined across tertiles of covariates. Analyses were hypothesis generating and exploratory in nature. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons.

Results

Table 1 shows the baseline participant characteristics by group. Table 2 shows bivariable associations of change in self-efficacy with baseline participant characteristics across the entire sample as well as in the tai chi only group. Exercise self-efficacy significantly improved in the tai chi group compared to the education control over 12 weeks (β=0.43; SE 0.12; p= 0.0005). There were trends seen with gender (β= −0.25 for male; SE 0.13; p=0.06) and age (β=0.009; SE 0.005; p=0.08), with females and older patients reporting greater improvements in self-efficacy. These associations were significant when examining the tai chi only group (β= −0.39 for male; SE 0.16; p=0.02 and β=0.01 for age; SE 0.007; p=0.05). Exercise self-efficacy, however, was not significantly associated with race (β= −0.03 for white; SE 0.19; p=0.89), ischemic etiology (β= −0.11 for ischemic; SE 0.13; p=0.39), baseline ejection fraction (β=0.006; SE 0.008; p=0.48), or baseline resting heart rate (β=0.002; SE 0.005; p=0.72).

Table 1.

| Tai Chi (n = 50) | Education (n = 50) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Median | (Q1, Q3) | Median | (Q1, Q3) | |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 28 (56) | 36 (72) | ||

| Race, White, n (%) | 43 (86) | 43 (86) | ||

| Age, y | 69 | (60, 76) | 66 | (60, 73) |

| Ischemic etiology, n (%) | 23 (46) | 31 (62) | ||

| Resting heart rate, beats/min | 72 | (63, 80) | 70 | (60, 80) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 28 | (22, 35) | 30 | (23, 35) |

|

| ||||

| MLHFQ, total score | 28 | (12, 47) | 21 | (11, 52) |

| SF-12 Short Form, mental score | 53 | (46, 59) | 51 | (46, 57) |

| SF-12 Short Form, physical score | 38 | (30, 45) | 40 | (30, 51) |

| POMS, tension and anxiety | 3 | (1, 7) | 4 | (2, 8) |

| POMS, depression | 2 | (0, 5) | 3 | (1, 6) |

| POMS, anger and hostility | 4 | (1, 7) | 5 | (2, 9) |

| POMS, vigor | 9 | (4, 11) | 8 | (5, 13) |

| POMS, fatigue | 6 | (2, 10) | 9 | (2, 10) |

| POMS, confusion | 4 | (3, 7) | 4 | (2, 7) |

| POMS, total mood disturbance | 10 | (3, 29) | 18 | (6, 30) |

| Sense of coherence, total score | 69 | (62, 77) | 66 | (57, 76) |

| Perceived social support, total score | 70 | (58, 78) | 63 | (54, 72) |

| Cardiac exercise self-efficacy, total score | 3.6 | (2.8, 3.9) | 3.7 | (3.1, 4.3) |

|

| ||||

| 6-minute walk test, m | 391 | (265, 475) | 392 | (277, 482) |

| Peak , mL/kg/min | 11.9 | (10.4, 15.7) | 13.5 | (10.0, 17.6) |

| Exercise duration, sec | 421 | (264, 554) | 432 | (282, 524) |

| Timed Up and Go, sec | 9.4 | (8.1, 11.7) | 9.3 | (7.4, 12.1) |

| CHAMPS, caloric expenditure/week | 1914 | (1057, 3864) | 2151 | (1100, 4820) |

| CHAMPS, frequency/week | 12 | (6, 21) | 15 | (7, 21) |

|

| ||||

| Epinephrine, pg/mL | 36 | (17, 50) | 28 | (18, 48) |

| Norepinephrine, pg/mL | 315 | (220, 548) | 374 | (260, 513) |

| Dopamine, pg/mL | 24 | (9, 56) | 32 | (13, 60) |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 3.2 | (0.9, 6.2) | 2.4 | (1.0, 8.0) |

| Tumor necrosis factor, pg/mL | 1.6 | (1.2, 1.9) | 1.6 | (1.0, 2.2) |

| Endothelin 1, pg/mL | 2.4 | (1.9, 2.9) | 2.1 | (1.8, 2.8) |

| B-type natriuretic peptide, pg/mL | 102 | (47, 212) | 106 | (43, 493) |

Abbreviations: CHAMPS, Community Healthy Activities Model Program for Seniors; MLHFQ, Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire; POMS, Profile of Mood States questionnaire; , oxygen uptake.

Data expressed as median (interquartile range), except where noted to be n(%).

No significant differences between groups at baseline.

Table 2.

Correlates of Change in Exercise Self-Efficacy with Baseline Characteristics

| Total Sample (N = 100) | Tai Chi only (N = 50) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| β (SE) | P-value | β (SE) | P-value | |

| Treatment, tai chi | 0.44 (0.12) | .0005 | ||

|

| ||||

| Sex, male | −0.25 (0.13) | .06 | −0.39 (0.16) | .02 |

| Race, White | −0.03 (0.19) | .89 | −0.42 (0.23) | .07 |

| Age | 0.009 (0.005) | .08 | 0.01 (0.007) | .05 |

| Ischemic etiology | −0.11 (0.13) | .39 | −0.08 (0.17) | .60 |

| Resting heart rate | 0.002 (0.005) | .72 | 0.006 (0.007) | .43 |

| Left ventricular ejection fractiona | 0.006 (0.008) | .48 | 0.00002 (0.01) | 1.00 |

|

| ||||

| MLHFQ, total scoreb | −0.0002 (0.003) | .95 | 0.0009 (0.004) | .81 |

| SF12 Short Form, mental scoreb | 0.006 (0.007) | .37 | 0.01 (0.008) | .12 |

| SF12Short Form, physical scoreb | −0.008 (0.006) | .18 | −0.01 (0.008) | .17 |

| POMS, tension and anxietyb | −0.04 (0.02) | .008 | −0.04 (0.02) | .08 |

| POMS, depressionb | −0.04 (0.02) | .02 | −0.04 (0.02) | .05 |

| POMS, anger and hostilityb | −0.03 (0.01) | .01 | −0.05 (0.02) | .004 |

| POMS, vigora | −0.004 (0.01) | .77 | −0.006 (0.02) | .73 |

| POMS, fatigueb | −0.03 (0.01) | .009 | −0.03 (0.02) | .08 |

| POMS, confusionb | −0.03 (0.02) | .18 | −0.03 (0.02) | .14 |

| POMS, total mood disturbanceb | −0.009 (0.003) | .01 | −0.009 (0.004) | .03 |

| Sense of coherence, total scorea | 0.004 (0.005) | .42 | 0.006 (0.008) | .45 |

| Perceived social support, total scorea | 0.006 (0.005) | .16 | 0.003 (0.006) | .67 |

|

| ||||

| 6-minute walk testa | −0.0004 (0.0001) | .004 | −0.0006 (0.0002) | .0007 |

| Peak VO2a | −0.03 (0.01) | .01 | −0.06 (0.02) | .0003 |

| Exercise durationa | −0.0008 (0.0003) | .004 | −0.001 (0.0004) | .0001 |

| Timed Up and Gob | 0.02 (0.007) | .02 | 0.02 (0.008) | .05 |

| CHAMPS, caloric expenditure/weeka | −0.00003 (0.00002) | .19 | −0.00005 (0.00003) | .09 |

| CHAMPS, frequency/weeka | −0.003 (0.007) | .59 | −0.008 (0.008) | .28 |

|

| ||||

| Epinephrineb | 0.0004 (0.0007) | .58 | 0.003 (0.001) | .04 |

| Norepinephrineb | 0.0001 (0.0002) | .65 | 0.0002 (0.0002) | .29 |

| Dopamineb | −0.00001 (0.0001) | .94 | −0.00002 (0.0001) | .86 |

| C-reactive proteinb | −0.005 (0.01) | .62 | 0.002 (0.01) | .89 |

| Tumor necrosis factorb | 0.006 (0.005) | .21 | 0.005 (0.004) | .30 |

| Endothelin 1b | 0.01 (0.05) | .77 | 0.09 (0.11) | .41 |

| B-type natriuretic peptideb | 0.00002 (0.0002) | .93 | 0.0005 (0.0003) | .10 |

Abbreviations: CHAMPS, Community Healthy Activities Model Program for Seniors; MLHFQ, Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire; POMS, Profile of Mood States questionnaire; SE, standard error; , oxygen uptake.

aHigher score more favorable.

Lower score more favorable.

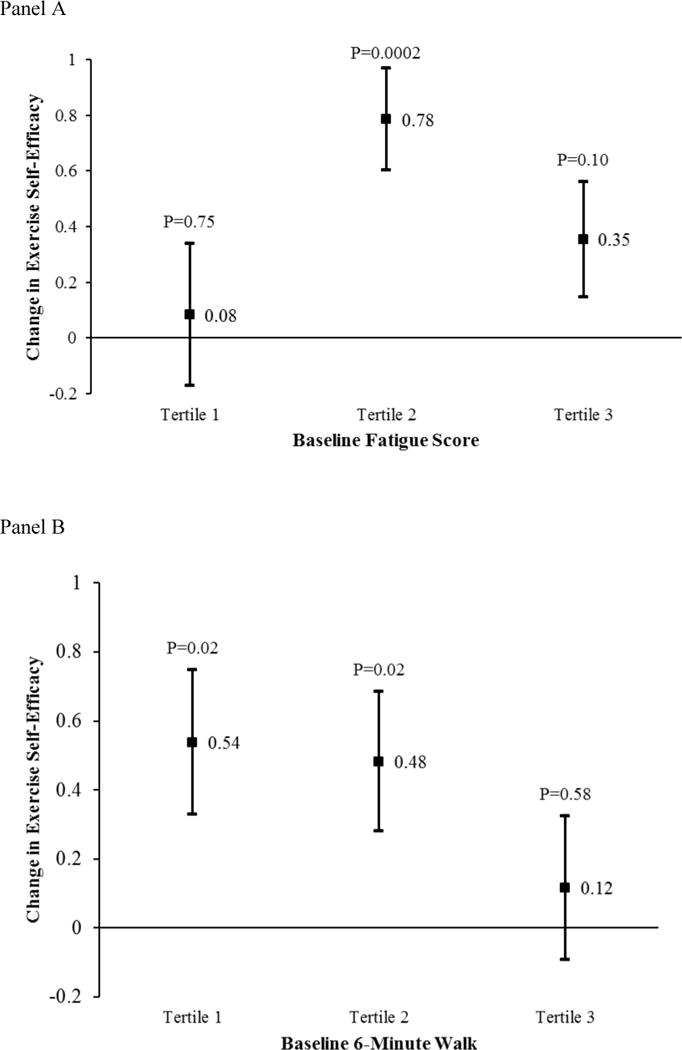

Table 3 shows results of the multivariable model examining factors associated with change in self-efficacy. In the adjusted model, tai chi remained significantly associated with improved self-efficacy (β=0.39; SE 0.11; p=0.0009). In addition, baseline 6-minute walk (β= −0.0003; SE 0.0001; p=0.02) and fatigue (β=0.03; SE 0.01; p=0.004) were selected into the final model. Figure 1 shows the associations of tai chi with change in self-efficacy across tertiles of these two variables. Those in the highest tertile (>459 meters) for baseline 6-minute walk and those in the lowest tertile (<5 points) for fatigue score had less change in self-efficacy.

Table 3.

Multivariable Model of Factors Associated with Change in Exercise Self-Efficacy in Overall Cohort of Patients with Chronic Heart Failure

| β (SE) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, male | −0.15 (0.13) | .23 |

| Age | −0.0004 (0.005) | .94 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | 0.008 (0.007) | .27 |

| 6-minute walk test | −0.0003 (0.0001) | .02 |

| POMS, fatigue | −0.03 (0.01) | .004 |

| Treatment, tai chi | 0.39 (0.11) | .0009 |

Abbreviations: POMS Profile of Mood States questionnaire, SE, standard error.

Figure 1.

Effects of Tai Chi on Change in Exercise Self-Efficacy across Tertiles of Baseline Fatigue and 6-Minute Walk

Table 4 shows results of the multivariable model examining factors associated with change in self-efficacy in the tai chi group only. In the final adjusted model, baseline peak oxygen consumption (β= −0.05; SE 0.01; p=0.001), mood (POMS Total Mood Disturbance score β= −0.01; SE 0.003; p=0.004), and catecholamine level (epinephrine β=0.003; SE 0.001; p=0.005) were significantly associated with change in exercise self-efficacy. When further examining these covariates in tertiles, both baseline mood and epinephrine exhibited a positive linear relationship, with increasing self-efficacy seen with increasing baseline values. The pattern with oxygen consumption exhibited a cutoff value in the lowest tertile, with only those with baseline values of < 11.2 ml/kg/min having a significant change in self-efficacy.

Table 4.

Multivariable Model of Factors Associated with Change in Exercise Self-Efficacy in Tai Chi Subgroup

| β (SE) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, male | −0.23 (0.13) | .10 |

| Age | −0.00003 (0.006) | .99 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | −0.0004 (0.007) | .95 |

| Peak | −0.055 (0.01) | .001 |

| POMS, total mood disturbance | −0.01 (0.003) | .004 |

| Epinephrine | 0.003(0.001) | .005 |

Abbreviations: POMS, Profile of Mood States questionnaire; SE, standard error.

Discussion

In patients with heart failure, we found that baseline functional capacity, as measured by 6-minute walk distance, and level of fatigue were associated with changes in self-efficacy over time. Those in our overall cohort with the highest functional capacity (>459 meters on 6-minute walk) had less improvement in exercise self-efficacy. To place this in context, the median (IQR) 6 minute walk distance in the HF-Action study (23) among patients with NYHA Class 2–4 heart failure was 372 meters (300, 434) The mean 6 minute walk of a healthy man in Boston (age 40–80 years) is about 549 meters.(24,25) Level of fatigue appeared to have a more nuanced relationship with self-efficacy, with those with more severe fatigue at baseline exhibiting positive change in self-efficacy, but not as much as those with moderate fatigue. In addition, we found that those who received 12 weeks of tai chi exercise as compared to an educational control had improved cardiac exercise self-efficacy. Among the subgroup who received tai chi, the correlates of change in self-efficacy were baseline exercise capacity as measured by peak oxygen consumption on a bicycle stress test and mood disturbance, with those with worse baseline scores having the larger improvements in self-efficacy over time. In addition, those with higher baseline epinephrine had larger improvements in self-efficacy.

Despite the limitations of this exploratory analysis, our results overall support preliminary literature suggesting that tai chi exercise may increase self-efficacy and importantly, the notion that tai chi may be suitable for those who are frail, deconditioned, who otherwise may not want to perform other exercise. One study of physically inactive adults (n=94) randomized patients to twice weekly tai chi for 6 months vs wait list control reported increases in self-efficacy with tai chi and this was also associated with increased exercise behavior.(12) Another small observational pilot of older Chinese adults (N=39) reported increases in self efficacy with 12 weeks of tai chi and this was associated with increased social support and mood, and decreased stress. (13)

Based on traditional self-efficacy theory (26) there are four important facilitators of self-efficacy: 1) “experience/enactive attainment”, 2) modeling, 3) social persuasion, and 4) physiological signals. Within this theoretical framework, there appear to be multiple relevant characteristics or components of tai chi that may contribute to increasing self-efficacy. The first facilitator refers to the notion that prior successes boost confidence. Multiple papers have reported significant functional gains with tai chi practice, including strength, balance, and cardiovascular endurance.(14) These experiences over time might allow participants to do more, even if in small increments, and this contributes to building self-efficacy. This may be particularly salient in those starting at lower functional capacity. The second facilitator is modeling which describes how seeing others succeed can contribute to self-efficacy, and the third is social persuasion which embodies the positive effects of group social support and peer encouragement. Each of these elements are paramount in a class of tai chi where all participants are part of a unique shared transformative experience, and the environment fosters connection, support and shared success. Recent qualitative studies linked to clinical trials of tai chi support the relevance of each of these first three facilitators of self-efficacy (15, 27,28). The fourth precept refers to physiological cues that can feed back on self-efficacy, and this can be positive or negative. For example, body signals such as fast heart rate or breathing due to anxiety or fear can negatively impact self-efficacy for a particular task. Tai chi and other mind-body exercises inherently teach mindfulness, body/self-awareness, acceptance, and non-reactivity that may act to mitigate this effect. Tai chi has also been shown to decrease fear of falling, (29,30) which may feed exercise self-efficacy and overall internal locus of control.

A better understanding of what drives self-efficacy and the development of strategies to improve exercise self-efficacy is important in HF. Based on evidence from multiple studies of HF and related chronic populations, programs of mind-body exercises like tai chi may enhance both psychosocial and physiological outcomes including quality of life, mood, and exercise capacity. (31,32). This study provides clearer indication of effects on exercise self-efficacy and explores the sub-populations of patients that might benefit most. We found the greatest impact on exercise self-efficacy in those with lower functional capacity, moderate levels of fatigue, poor mood, and higher stress hormones. Along with support of relative safety and accessibility, mind-body exercise may be a catalyst for physical activity for more difficult and deconditioned HF patients.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This study was supported by an award from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (Phillips, R01AT002454).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Peter Wayne is the founder and sole owner of the Tree of Life Tai Chi Center. Dr. Wayne’s interests were reviewed and are managed by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Partners HealthCare in accordance with their conflict of interest policy.

Trial Registration: This trial is registered in Clinical Trials.gov, ID number NCT00110227

References

- 1.Davies EJ, Moxham T, Rees K, et al. Exercise training for systolic heart failure: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12:706–15. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies P, Taylor F, Beswick A, et al. Promoting patient uptake and adherence in cardiac rehabilitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;6:CD007131. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007131.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbour KA, Miller NH. Adherence to exercise training in heart failure: a review. Heart Fail Rev. 2008;13:81–9. doi: 10.1007/s10741-007-9054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Du H, Everett B, Newton PJ, Salamonson Y, Davidson PM. Self-efficacy: a useful construct to promote physical activity in people with stable chronic heart failure. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21:301–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maeda U, Shen BJ, Schwarz ER, Farrell KA, Mallon S. Self-efficacy mediates the associations of social support and depression with treatment adherence in heart failure patients. Int J Behav Med. 2013;20:88–96. doi: 10.1007/s12529-011-9215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burns KJ, Camaione DN, Froman RD, Clark BA. Predictors of referral to cardiac rehabilitation and cardiac exercise self-efficacy. Clin Nurs Res. 1998;7:147–63. doi: 10.1177/105477389800700205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petter M, Blanchard C, Kemp KA, Mazoff AS, Ferrier SN. Correlates of exercise among coronary heart disease patients: review, implications and future directions. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2009;16:515–26. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3283299585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woodgate J, Brawley LR. Self-efficacy for exercise in cardiac rehabilitation: review and recommendations. J Health Psychol. 2008;13:366–87. doi: 10.1177/1359105307088141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodgers WM, Murray TC, Selzler AM, Norman P. Development and impact of exercise self-efficacy types during and after cardiac rehabilitation. Rehabil Psychol. 2013;58:178–84. doi: 10.1037/a0032018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tierney S, Mamas M, Skelton D, et al. What can we learn from patients with heart failure about exercise adherence? A systematic review of qualitative papers. Health Psychol. 2011;30:401–10. doi: 10.1037/a0022848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarkar U, Ali S, Whooley MA. Self-efficacy as a marker of cardiac function and predictor of heart failure hospitalization and mortality in patients with stable coronary heart disease: findings from the Heart and Soul Study. Health Psychol. 2009;28:166–73. doi: 10.1037/a0013146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li F, Harmer P, McAuley E, Fisher KJ, Duncan TE, Duncan SC. Tai Chi, self-efficacy, and physical function in the elderly. Prev Sci. 2001;2:229–39. doi: 10.1023/a:1013614200329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor-Piliae RE, Haskell WL, Waters CM, Froelicher ES. Change in perceived psychosocial status following a 12-week Tai Chi exercise programme. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54:313–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang C, Collet JP, Lau J. The effect of Tai Chi on health outcomes in patients with chronic conditions: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2004 Mar 8;164:493–501. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.5.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer M, Fugate-Woods N, Wayne PM. Use of pragmatic community-based interventions to enhance recruitment and adherence in a randomized trial of Tai Chi for women with osteopenia: insights from a qualitative substudy. Menopause. 2014 May 19; doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000257. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeh GY, McCarthy EP, Wayne PM, et al. Tai chi exercise in patients with chronic heart failure: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:750–7. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hickey ML, Owen SV, Froman RD. Instrument development: cardiac diet and exercise self-efficacy. Nurs Res. 1992;41:347–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rector TS, Tschumperlin LK, Kubo SH, et al. Use of the Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire to ascertain patients’ perspectives on improvement in quality of life versus risk of drug-induced death. J Card Fail. 1995;1:201–206. doi: 10.1016/1071-9164(95)90025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppelman LF. Manual for the Profile of Mood States. San Diego, CA: EDITS Educational and Industrial Testing Services Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 20.ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS Statement: Guidelines for the Six-Minute Walk Test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111–117. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bellet RN, Francis RL, Jacob JS, et al. Timed Up and Go Tests in cardiac rehabilitation: reliability and comparison with the 6-Minute Walk Test. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2013;33:99–105. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e3182773fae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stewart AL, Mills KM, King AC, Haskell WL, Gillis D, Ritter PL. CHAMPS physical activity questionnaire for older adults: outcomes for interventions. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:1126–41. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200107000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Lee KL, et al. HF-ACTION Investigators Efficacy and safety of exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:1439–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casanova C, Celli BR, Barria P, et al. Six Minute Walk Distance Project (ALAT) The 6-min walk distance in healthy subjects: reference standards from seven countries. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:150–6. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00194909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rostagno C, Olivo G, Comeglio M, et al. Prognostic value of 6-minute walk corridor test in patients with mild to moderate heart failure: comparison with other methods of functional evaluation. Eur J Heart Fail. 2003;5:247–52. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(02)00244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang Y, Decelle S, Reed M, Rosengren K, Schlagal R, Greene J. Subjective experiences of older adults practicing taiji and qigong. J Aging Res. 2011;2011:650210. doi: 10.4061/2011/650210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu E, Barnes DE, Ackerman SL, Lee J, Chesney M, Mehling WE. Aging Ment Health. Preventing Loss of Independence through Exercise (PLIÉ): qualitative analysis of a clinical trial in older adults with dementia. 2014 Jul 14;:1–10. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.935290. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zijlstra GA, van Haastregt JC, van Rossum E, van Eijk JT, Yardley L, Kempen GI. Interventions to reduce fear of falling in community-living older people: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:603–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hackney ME, Wolf SL. Impact of Tai Chi Chu’an practice on balance and mobility in older adults: an integrative review of 20 years of research. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2014;37:127–35. doi: 10.1519/JPT.0b013e3182abe784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pan L1, Yan J, Guo Y, Yan J. Effects of Tai Chi training on exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure: a meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:316–23. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woltz PC1, Chapa DW, Friedmann E, Son H, Akintade B, Thomas SA. Effects of interventions on depression in heart failure: a systematic review. Heart Lung. 2012;41:469–83. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]